Chapter 14

The Essential Ingredient

Without question, equity returns lie at the heart of corporate wealth creation. In turn, quality business models lie at the heart of corporate equity returns. Such business models are conceived, adopted, and executed by founding corporate entrepreneurs and business leaders, often with material assists from company management and staff. While much of the focus on this book is centered on the financial dynamics and basics of corporate wealth creation, business models do not execute themselves. Human effort drives business model creation and execution. It is the essential ingredient.

The Growing Restaurant Illustration

In chapter 10, to illustrate the power of OPM equity, I presented a case of a growing restaurant enterprise. The sample company starts with a single location funded with YOM and OPM in year one, adding a second location in year two funded with OPM equity and OPM. Over the next three years, the company adds another eight locations that are funded with retained equity cash flows and OPM. The case study is feasible, and I have witnessed companies successfully embark on similar aggressive growth strategies.

Do not take my rosy corporate scenario to mean that I believe execution to be easy. There are more restaurant locations in the world than any other service or retail establishment. The restaurant industry is mature and highly competitive, with new restaurant successes typically won at the cost of market share taken from other restaurant locations. In a broader sense, restaurants also compete for a “share of stomach” with supermarkets, convenience stores, movie theaters, and other participants. Gaining and keeping restaurant market share is hard.

Whereas entrepreneurs engaged in mature industries like the restaurant industry tend to be driven by grabbing a piece of the market share pie, novel business enterprises aim to get in on the ground floor of pie creation. Both strategies have distinctive execution risks, and both are capable of EMVA creation.

While there are just six financial variables that collectively comprise corporate business models, there are nearly infinite operational alternatives that stand behind the numbers and the resultant equity returns. This universal truth demands capable leadership. When it comes to the restaurant industry, the following provides a small flavor of the many operational considerations that need to be addressed in conceiving a viable business model:

- Hours of operation: What are your hours of operation? Do you serve breakfast, lunch, and dinner? Are you open seven days a week?

- Menu offerings: How many menu offerings do you have?

- Beverages: Do you serve alcoholic beverages?

- Service: Do you have no-, partial-, or full-table service?

- Take out: Do you have a drive-thru window or other means to pick up food to go?

- Delivery: Do you deliver food or partner with food delivery services?

- Internet: Do you have online ordering or reservations?

- Reservations: Do you accept table reservations?

- Staffing and management: How much staffing and management do you require?

- Advertising: How much and what type of advertising might you need?

Restaurants, like nearly all businesses, are complex, involving hundreds of operational design considerations. Restaurants are also people intensive, with labor typically representing the greatest financial burden. It follows that labor effectiveness is absolutely impacted by the quality of training, the level of staff motivation, the corporate goals established and the financial incentives to achieve those goals, all of which are reflections of corporate leadership and its strategic vision.

Business operational strategies are never as simple as the Six Variable financial business model they ultimately form. Monty Williams joined my hometown NBA team, the Phoenix Suns, in 2019 as their head coach and is fond of saying, “Everything you want is on the other side of hard.”

EMVA creation can be like that.

Designed Structural Change

I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to contribute to the creation of three corporate business models. Each of the three companies we created was engaged in a similar business: all owned real estate across the country integral to the operations of our many tenants. Because we conceived each company, we were able to design their operating models at the outset. And because each company was in a similar line of business, we were able to learn from our prior experiences to improve our business models with each successive corporate formation.

Our earliest company grew to manage approximately $6 billion in real estate assets prior to its eventual 2001 sale to GE Capital. We were vertically integrated at the time, having more than 200 employees directly engaged in an array of activities, from new business origination to portfolio management. We had staff that monitored the insurance and property taxes at each location. We had a complete information technology team, including full-time programmers, to create and manage our proprietary portfolio servicing and accounting platforms. We had what amounted to an internal law firm, with lawyers and paralegals helping us with legal matters arising from our complex business activities. At the heart of our organization was an impressive sales team capable of originating and closing well over $1 billion in new investments annually. At the time we sold our organization to GE Capital, we believed our operating model was the state of the art.

Scarcely two years later, when we had the chance to start our second company, we changed our minds and radically altered our organizational structure. Technology had changed and so had our personal perspective. So, we set about to implement a series of designed structural modifications:

Technology-Enabled Changes

We are fortunate to live in an era characterized by rapid technological advances that can have profound impacts on corporate operational models. With change a given, all businesses should be in a constant state of technological reevaluation as they seek out potential efficiencies.

I learned this early on in my career, when I persuaded the president of the bank that employed me to buy its first ever personal computer. That device was used to spread the corporate financial statements of bank customers and launched me on my path to better understand corporate business models. Since then, the pace of technological change has been blinding, which has had a profound impact on corporate business models.

One of the first things we decided to do when starting our second company was to outsource nearly all our information technology needs. We still had a server on site, but it was relegated to a closet together with our telephone infrastructure. Gone were the days where I could show off a massive computer and backup tape array sitting on an elevated cooled floor and protected by a halon fire extinguisher. Information technology had changed, with increasing platform standardization and integration that made it feasible to outsource. In doing so, we eliminated a high fixed cost, converting it to a reduced variable cost.

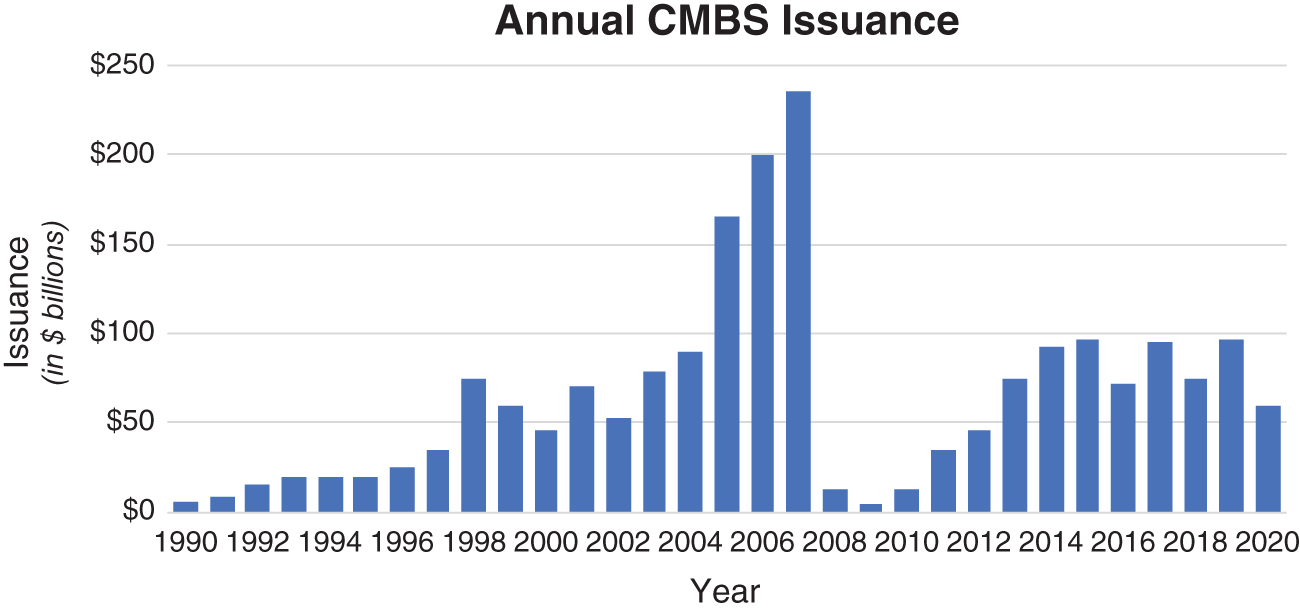

We also decided to outsource the administrative aspects of portfolio servicing, including rent collections, together with the monitoring of property taxes and insurance. Our earliest monitoring platform was largely designed in the 1980s. However, the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) market emerged in 1990, toward the conclusion of the Savings and Loan Crisis and inspired by the success of residential mortgage securitizations. Basically, this meant that loans against commercial real estate were pooled, tranched, rated, and sold off to institutional fixed income investors. But for this to happen required the emergence of professional portfolio servicing companies, who would remit the payments to the investors and monitor the loan portfolios. What were three of the major functions performed by these servicing companies? You got it; they collected payments and monitored real estate taxes and property insurance policies. We approached a few of these companies to see if they might be willing to provide a similar service for a portfolio of leased real estate. In taking this approach, we again took large, fixed costs, converting them to smaller variable costs. Outsourcing these labor and systems intensive tasks also had the benefit of improved security and controls that we and our OPM providers welcomed.

SOURCES: Data from Chandan Economics and J.P. Morgan Securities and Commercial Real Estate Direct

Core Competency Refinement

Core competencies are defined as identified essential skills tethered to the problems and stakeholders that businesses are designed to address.

Companies tend to be best off if they can identify and refine their core competencies and focus on them with minimal distraction. Simply deciding on core competency focus requires discipline and can take some time. Fortunately, we had time, starting our version 2.0 investment platform more than 20 years after the first.

Information technology and legal services were not our core competency. I was a businessperson and a finance professional and so reasonably uninformed when it came to the evaluation of the effectiveness of our IT and legal services departments.

One day, the head of our network administration came into my office and made a pitch: He wanted a SANS system (SANS stands for SysAdmin, Audit, Network, and Security) to improve the redundancy and security of our company's IT infrastructure. The cost was $1 million, and his proposal was supported by the department head. I was lost. However, I approved the investment, making a vow to one day figure out how to outsource as much of the IT function as possible. We were not in the business of making or marketing software. Our business was to provide real estate capital solutions to our customers.

I was as mystified by legal services as by information technology. On another day I was approached by one of our internal counsel who was eager to inform me how much money he had saved us in a legal matter. The implication was that having internal counsel so familiar with our business enabled this type of result. I remember simply wondering if I were one of the luckiest people alive or whether, somewhere, I might have engaged outside counsel to achieve a similar result. I had no real way of knowing for sure, but that was the point. In a small company like ours, I felt unqualified to lead or assess an internal law firm. Like IT, this could never be a core competency.

When we started our second company, we had a single general counsel and no legal department.

One of the risks in our business is that we make investments with documentation and terms not matching our initial transaction approval. All finance companies bear this risk. In banking, they have personnel devoted to the review of extended loans to be certain that they were funded as initially approved. We had a similar department in our earliest company. The problem for us was that, unlike a bank, we had far less ability to influence our customers to make subsequent changes in the event of an error. So, we arrived at a solution to eliminate the quality control department. Instead, we elected to have our outsourced external legal counsel certify that the transactions they closed conformed with the terms of our approval. Quality would be built into our investment process up front where it mattered most.

Our earliest company also had an investor relations department, which stemmed from our history of having raised our earliest capital directly from retail investors through the stockbrokers they used. However, given greater corporate communication regulatory complexity, together with our changing investor landscape, we elected to also outsource this function. Unlike our other outsourcing endeavors, doing so did not save money or materially add to our operating efficiency. It simply made us better and again acknowledged a function that could not be a core competency.

We made one more key organizational change. We redesigned our sales force to have no direct reports. Salespeople are always among the most valued professionals in any organization. At our earliest platform, our investment origination professionals each oversaw support personnel, who they hired as needed. Given that expanded teams of people was costless to our commissioned salesforce, representing a miserable alignment of interest, we had two choices: We could make each sales territory a profit center, charging them for their resources, or we could simplify their organization structure, shifting their support staff to other departments. We selected the simpler second option.

We also made a material OPM change, choosing to abandon the corporate investment-grade rating and unsecured borrowing approach pioneered by our earliest platform in favor of a flexible investment-grade secured financing approach that we developed. That served to slightly elevate our OPM mix, increasing our ROE and making our capital stack fully assumable, which proved important in delivering shareholder returns upon the eventual 2007 company sale.

Four years later, we started STORE Capital, which would be version 3.0 of our real estate net lease strategy. Our chosen name, which stands for Single Tenant Operational Real Estate, represented an investment focus refinement; we elected to invest in only commercial freestanding profit center properties. We also elected to have a far more diverse investment portfolio. When it came to our operations, we retained all our prior version 2.0 modifications, adding a few more designed structural modifications, including:

- Outsourcing tenant financial statement capture, turning a fixed cost into a variable cost.

- Improving the integration of our IT systems with our outsourced service providers.

- Segmenting our origination team between direct and broker-originated opportunities.

- Adding a portfolio management department.

- Moving to exclusively cloud-based computing solutions,

- Increasing resources dedicated to investment origination activities.

- Using complementary secured and unsecured investment-grade OPM.

Technology-enabled enhancements continued to play a role in our operating model evolution. Now we no longer even had a computer server in the closet. Together with the systems and software we employed, our computer platforms were housed in multiple off-site data centers. This evolution will have a lasting impact on STORE's ability to execute future operational enhancements.

One of the key takeaways gained from starting our second platform was the importance of designing and establishing a strong and flexible IT foundation from the start. With version 2.0, our founding private OPM equity investors expected us to file for an initial public offering a mere six months after having raised our first equity capital. We did so, publicly listing the company almost exactly a year from the date we officially opened our doors for business. This rapid scheduling contributed to an oversight. We started our company on an insufficiently robust IT platform, spending insufficient time on overall system design. Over time, this shortcoming would result in elevated costs, from personnel to time to the ultimate need to implement and design a complete system conversion.

Lesson learned.

Collectively, the version 2.0 and 3.0 designed operational enhancements we made were impactful. By the end of 2020, STORE Capital managed nearly twice the amount of capital of our earliest operating platform, but with about half the staff. But numbers do not tell the whole story. Our staff mix included more sales, credit, and closing professionals than our earliest platform, serving to give us far more potent business origination capabilities. What is more, having outsourced most administrative tasks, our staff was now largely comprised of professionals.

Keeping It Simple

Operational changes, like the ones we have executed over the years, are broadly designed to lower business investment needs, elevate operating profit margins and improve capital efficiency. They are also designed to improve the simplicity of the corporate operating model, while allowing the business to focus on what we are good at: Our core competencies.

One of my business model observations is that companies are like organic life forms. The founders hire the earliest staff. In turn, assuming the company is successful and starts to grow, those employees hire other employees. Eventually, your expanded staff begins to make organizational adjustments. Ten years after co-founding STORE, there were many aspects of our processes in which I had little personal input. However, the essential organizational structure conceived by me, and the other STORE founders remained in place. So did the basic potent business model we created. They are effectively the canvas on which future leaders paint.

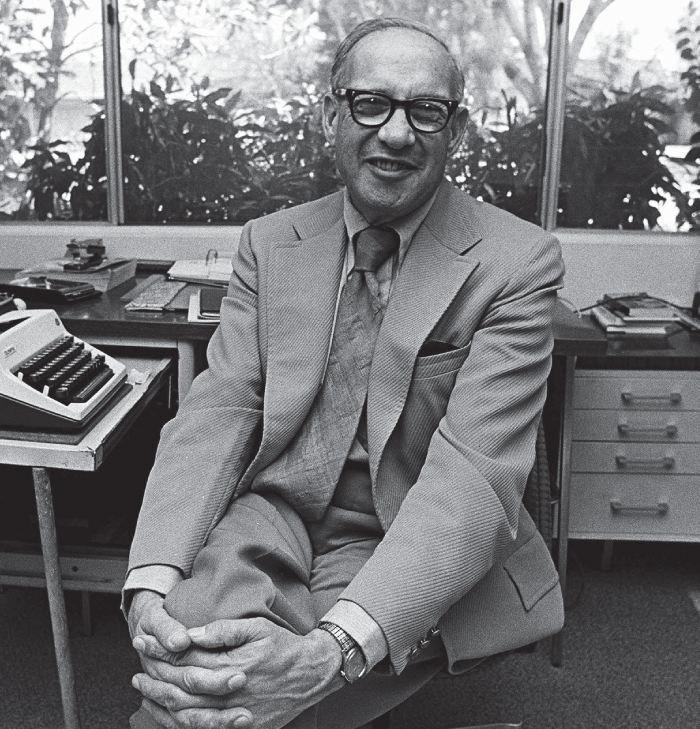

Peter Drucker

Credit: George Rose/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In his groundbreaking 1946 book The Concept of the Corporation, management pioneer Peter Drucker keenly observed, “No institution can possibly survive if it needs geniuses or supermen to manage it. It must be organized in such a way as to be able to get along under a leadership composed of average human beings.”

I agree. With fewer employees and fewer departments, our goal over the years has been to simplify a business organization structure to be more centered on our core competencies and corporate objectives.

A clear benefit of well-crafted business organization structures is that they tend to broadly distribute leadership responsibilities, giving senior executives more time to attend to strategic planning and initiatives. When it comes to the daily corporate administration within a potent business organization, senior executives become less important. I have seen this first-hand. Members of the leadership team that started STORE Capital collectively departed our predecessor company without being replaced for nearly two years. The version 2.0 business we founded and the operational model we launched functioned well, eventually enabling the company to be reintroduced to the public markets.

In 1954, Peter Ducker famously introduced the concept of “management by objectives” (MBO), the central idea being that key objective determination enables performance measurement and better goal setting. Of course, objectives tend to center around corporate core competencies, and both can take considerable time and thought to develop. In our case, we had that time. At the inception of the operational design changes implemented in our second company, we had a leadership team comprised of members who each had experience with our earliest platform ranging from 10 to more than 20 years. Eight years later, that same team would collectively work on the formation of STORE to create a more refined organizational and operational canvas.

Planned vs. Imposed Structural Change

Business models are forever subject to change. That change can result from planned designed structural change as laid out in the evolution of STORE's corporate model over the years or change can be imposed by external forces. Failing to respond to imposed external changes can risk corporate relevance and survival.

No businesses are immune from externally imposed business model changes. Restaurants are no exception. Dining establishments that have not addressed changing consumer access preferences have paid a price. Smart phone applications, gift cards, and online ordering and reservations are conveniences that consumers have grown to expect. To address rising labor costs, restaurants have implemented solutions ranging from connected computer tablets to varying methods of limited table service to automated labor scheduling, among other innovations. The successful adoption of elevated cost controls or changing consumer access preferences has had a definite impact on the big three business model variables that individually and collectively most impact EMVA creation.

Externally imposed business model changes can be anticipated or unanticipated. The former is definitely best. Unanticipated imposed business model changes can demand a shorter required response time, which can seem to observers to be both reactive and defensive, raising business vulnerability. Business model changes often entail organizational and operational changes, not to mention corporate competency reevaluation, and are best done with the benefit of time.

I have had experience with both unanticipated and anticipated imposed external business model changes. In 1988, we lost our principal source of investment funding with the demise of EF Hutton, a prominent New York City–based investment bank founded in 1904. The company was taken down in short order by a series of criminal indictments. That imposed and unanticipated change would cause us to redirect our fundraising efforts and organization to other investors, a process that both set back our growth and took some time.

Four years later, we set about to address an anticipated imposed change. We embarked on a plan to publicly list the majority of our managed real estate investments. While our investors were not demanding liquidity, we anticipated they would one day hold a different view. So, we embarked on a move to take our first company public. The entire process entailed some risk, took two years to accomplish, and holds the record of the largest real estate partnership roll-up ever completed. Our successful public listing would naturally have profound changes on our operational and business model.

A key part of business leadership is staying on top of externally imposed changes, trying to avoid unanticipated surprises. I'd like to think our leadership teams have done a pretty good job of this over the years, but I am fond of telling a story about dodging one such bullet.

In 1996, two years after taking our first company public, I was sitting in a law office at Two World Trade Center. I was there to close our inaugural secured bond issuance, the proceeds of which were used to finance a pool of chain store mortgages we had extended to our customers. The amount of the bond issuance was approximately $180 million, a material amount, and I prepared to sign a sea of papers that were organized on a board table, standing tall in a cascade of aluminum accordion document holders. But as I entered the room, it became clear that the assembled investment bankers, lawyers, and accountants were nervous and I was about to learn why.

Our bond tax counsel entered the room to inform me that there was a risk that we would be unable to close the transaction. In fact, there was a risk that we would have to return the bond proceeds to the investors that we had successfully solicited. Such an outcome would have been both painful and embarrassing, and so I began to run through alternatives in my mind. I also began to wonder how I could possibly be caught facing unanticipated externally imposed change given the many experts we had engaged. The reason for this predicament was pending tax legislation that was to potentially be included in a tax bill set to emerge from the House Ways and Means Committee that afternoon. So, we were told that we should just be prepared to wait until the bill emerged. At the time, I was comforted to know that our investment banking, legal, and accounting experts were willing to use their extensive government relations staffs to uncover the answer as soon as possible. With nothing else to do, we went to lunch.

Upon our return, no progress had been made and the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee had yet to emerge with proposed tax legislation. At the time, cell phones and email were emerging and not yet a business fixture. Google would be founded a few months later. But this was a fancy law firm and there was a phone booth. So, I went in, dialed the number for directory assistance and requested the phone number for the House of Representatives. With that number, I telephoned Congress and asked if I might be put through to the House Ways and Means Committee room. The receptionist put me through, and a legislative aid picked up the phone. I then presented my predicament and asked if he had knowledge about the specific tax issues that had the potential to kill our pending bond issuance. He did and told me that I needn't worry and that we should be good to proceed with our bond closing. Of course, I required some evidence and so he kindly faxed me the appropriate language from the pending tax legislation.

We quickly closed the bond issuance, and I was grateful to have avoided an unanticipated externally imposed change. And I naturally felt self-satisfied, having found an answer that had eluded the many knowledgeable experts we had engaged. I also felt encouraged that I could cold call Congress and find people there kind enough to stop what they were doing for a moment to help me. We had failed to see the potential for externally imposed change coming. But, faced with this reality, I did what is expected of leaders: I took the initiative to find a solution.

One of the most common questions public company business executives get is this: “What keeps you awake at night?” We have done our level best to sleep well across the three public companies we have guided. That said, unanticipated externally imposed changes loom large when it comes to business risk. Over the years, such events can be impactful, from our early E.F. Hutton experience, to the savings and loan crisis around the same time to the 1998 demise of Long Term Capital Management, the dot-com implosion two years later, the great recession eight years after that and the global pandemic that began in 2020. Unanticipated externally imposed change is a constant force that demands business model prudence and material margins for error.

Blockbuster Video

When it comes to a failure to respond to anticipated externally imposed change, former video rental pioneer Blockbuster Video stands tall. The first Blockbuster location opened in Dallas, Texas, in 1985, with the company becoming publicly listed a year later. In 1987, the company was taken over and led by serial entrepreneur Wayne Huizenga who, through franchising, corporate store development and acquisitions, grew the chain to more than 3,700 video rental and another 540 music store locations by the end of 1994. With company revenues approaching $3 billion, Huizenga anticipated imposed change was on the horizon. He had concerns about video on demand and the growing potency of cable television. At the end of 1994, Huizenga guided Blockbuster to a merger with diversified media giant Viacom for an equity value of $8.4 billion that proved valuable. When he died in 2018, he ranked inside the top 300 richest people in America, with a reported net worth approaching $3 billion.

Huizenga's successor at Blockbuster was former Taco Bell CEO John Antioco, who continued the company's rapid rise, growing the number of locations to more than 9,000 by 2004. However, he also saw that change was coming. The advent of DVD technology resulted in higher levels of movie sales. It also made it feasible to rent movies by sending DVDs through the mail. That was the idea of Netflix founder Reed Hastings, who approached Antioco in 2000 to sell his nascent and money losing company for $50 million.1 Blockbuster had an asset-heavy business model with many retail locations throughout the world. By contrast, Netflix employed a more asset-light model. Given Blockbuster's customer base, the Netflix model could be expected to become profitable more rapidly. But it would come at an enormous cost to Blockbuster's existing business model and franchisee base, entailing substantial and painful changes. Blockbuster declined, and Netflix went public in 2002. Two years later, Viacom, electing to not address Blockbuster's challenges, spun off the vulnerable business unit into a freestanding public company.

The future of video watching did not reside in Blockbuster's rental model. But it was not in the rental by mail Netflix business model, either. It centered in video on demand, which Netflix began to roll out in 2007. Likewise, Blockbuster introduced its Total Access online rental service the same year in a $1 billion promotional campaign. The costs to make such a business model change were enormous and were accentuated by the company's decision to abandon its unpopular late fees. At its height, video rental late fees amounted to more than 15% of Blockbuster's revenues, but an even greater portion of earnings, since they fell straight to the bottom line. Activist shareholder Carl Icahn was displeased, gained three board seats in a proxy battle, and ultimately installed a new CEO who abandoned the transition to online rentals. With the playing field for online video rentals ceded to Netflix, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy protection a mere three years later.

Sometimes companies have a hard time responding to anticipated, externally imposed change. The costs to respond can be enormous and the changes to the operational and business models gut-wrenching. Eastman Kodak ironically created the instrument of its own externally imposed change when it patented the first digital camera in 1975. During the twentieth century, Kodak dominated the global sales of camera film and film processing. Competing with its own lucrative film leadership to promote and invest in a technology having an uncertain business model proved elusive. The company filed for bankruptcy protection in 2012, scarcely more than two years following the demise of Blockbuster.

SOURCE: Data from Corporate SEC Filings

Anticipated, externally imposed changes are like the proverbial train light coming at you in a long, dark tunnel. You can see the train coming, but often have no idea how far away it is. As real estate investors in our earliest company, we foresaw the eventual closure of Blockbuster stores, if not the eventual failure of the company. But the changes happened far later than we initially expected.

Technological change lies at the center of many imposed business model changes. As I write this, the rising automotive market share taken by electric vehicles, as well as the potential for driverless vehicles, are just two technologies that will have repercussions across many industries. Sometimes imposed business model changes result from governmental actions, which can include environmental regulatory changes, or alterations in tax and tariff frameworks, just to name a few. When external imposed changes happen, they compel any number of industries to adapt or risk their relevance. As Blockbuster and Kodak demonstrate, the anticipated imposed changes required can occasionally be simply too painful to execute.

Designed Revolutionary Change

It is highly risky for businesses to radically alter their business models mid-stream. But every now and then, businesses embark on successful designed changes to their business models that are revolutionary.

In 1997, with the company suffering losses, Apple invited its co-founder and original visionary Steve Jobs to return. A year later, the company introduced its inaugural iMac computer, resulting in the company posting its first profit since 1995. The all-in-one design and ease of use of this compelling computer, which came in an array of colors, helped sustain Apple's near-term profitability. Earnings were also bolstered by the company's difficult decision to discontinue its unprofitable Newton product, an early personal digital assistant that incorporated handwriting recognition. In 1999, earnings nearly doubled before retrenching to a small loss in 2001. But despite the loss, 2001 would arguably prove to be Apple's most significant and momentous year, setting the groundwork for radical improvements in its future business model.

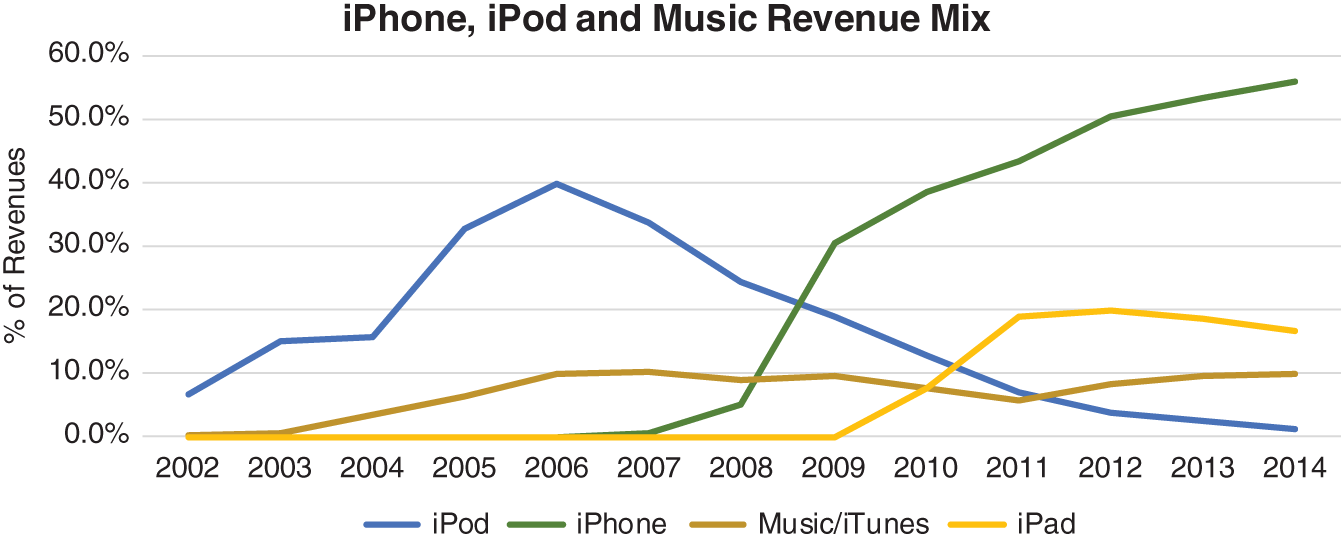

Over an eight-month period in 2001, Apple designed and introduced the iPod, an MP3 player that would revolutionize the digitized music industry. In January of the same year, the company announced the creation of iTunes, with the first Apple Store introduced four months later.2 Collectively, these moves set the foundation for Apple's eventual leadership in establishing an integrated entertainment environment. Five years later, the company's iPod sales approached $8 billion, amounting to almost 40% of corporate revenues. And 10 years after it was introduced, cumulative iPod unit sales exceeded 300 million, representing an eye-popping 78% market share of portable digital media sales.3

In 2007, another momentous year, Apple introduced its groundbreaking iPhone product, which would ultimately “featurize” iPod capabilities, incorporating them inside an appealing, cutting edge and feature-laden smartphone. As a result, iPod sales predicably declined, falling to 1% of company revenues over the next seven years, while iPhone revenues rose to more than 55% of company revenues. Three years after launching the iPhone, Apple introduced the iPad, a mobile tablet computer resembling in appearance a larger version of the company's successful iPhone. Like the iPhone, the iPad also incorporated the capabilities initially introduced with the iPod, while integrating seamlessly into the company's growing entertainment environment. Meanwhile, iTunes store sales, which were made possible with the 2001 introduction of the iPod, grew to exceed $18 billion, amounting to close to 10% of total revenues. By 2020, iPhone revenues continued to exceed 50% of company revenues, with recurring service revenues, which includes iTunes, growing to over $53 billion, representing nearly 20% of company sales. What was formerly a barely profitable personal computer company upon the return of Steve Jobs in 1997 had been radically transformed, pivoting to a far more potent business model that vaulted Apple into one of the world's most valuable companies.

Apple could no longer be viewed as a personal computer company. By 2020, sales of Mac computers were scarcely more than 10% of corporate revenues.

When asked about Apple's vision, CEO Steve Cook stated in 2009, “We believe that we are on the face of the earth to make great products and that's not changing. We are constantly focusing on innovating.”

With these words, Steve Cook put an exclamation point on Apple's continued openness to future designed revolutionary change.

SOURCE: Data from Company SEC 10-K Filings

Reengineering the Corporation

Embarking on corporate planned or externally imposed changes involves reengineering a company's operational models, ultimately impacting the corporate business model as reflected at a high level by its six financial variables. There's even a name for this: business process reengineering (BPR), a concept credited to Michael Hammer and Thomas Davenport while collaborating professors at MIT and Babson respectively in the late 1980s.4 In 1993, Hammer and co-author James Champy published Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, among the best-selling business books of all time. While the book was highly influential, Hammer and Champy noted that corporate reengineering is difficult, with a modest rate of success not far off from that of public company mergers. The reasons for reengineering failure can be many, ranging from a lack of planning and communication to fears of change and resultant corporate culture impact.

Description: Drs. Michael Hammer and Thomas Davenport, corporate reengineering pioneers.

My observation has likewise been that designed structural changes can be transformative, but difficult. Sometimes designed changes occur in response to changes in technology. Sometimes, they occur as business missions and core competencies are refined. Sometimes they occur in response to anticipated imposed external events. Sometimes, a need to reengineer a business model occurs in response to unanticipated imposed external events. Finally, there is always the unfortunate potential for an unanticipated internal event, which typically arises from human error.

I believe that corporate reengineering is best and least risky if it is constantly done. In that light, business model changes tend to be more evolutionary and less revolutionary, with corporate cultures open to constant self-assessment and change. Those cultures might rely on applied business tools, such as Peter Drucker's management by objectives, or Six Sigma, a set of techniques developed at Motorola designed to elevate quality through process changes.

Any process-designed reengineering roadmap is no substitute for thoughtfulness and insight. As Peter Drucker observed, leaders often fail to focus on meaningful objectives in their attempt to implement MBO, making the exercise ineffective. Likewise, Six Sigma process success is centered on defining the right problems to be solved and then having the right people in the room to solve them. I have witnessed failure on both accounts, where the problems to be solved were insufficiently meaningful and where the correct process stakeholders were not included in the exercise.

Reengineering efforts, to be impactful, require an elevated vision and participation from key staff members from across the business, with an aim to address the biggest, most strategic and impactful corporate challenges and opportunities.

No business is immune from a need to constantly reengineer. Certainly, any company undergoing meaningful growth will require a steady diet of process and business model reengineering. Such will be true of the start-up restaurant company in chapter 10 having aggressive plans to grow to 10 units over a brief five-year period. During that period, there will likely be anticipated designed operational changes, together with imposed changes that may be anticipated or unanticipated.

Peter Drucker once stated, “Whenever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision.”

I believe that strong successful business cultures are those that never cease to make courageous decisions.

Notes

- 1. Minda Zetlin, “Blockbuster Could Have Bought Netflix for $50 Million, but the CEO Thought It Was a Joke,” Inc. Magazine, September 30, 2019.

- 2. History.com, “Apple Launches iTunes, Revolutionizing How People Consume Music,” September 6, 2019, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/apple-launches-itunes.

- 3. Sherilyn Macale, “Apple Has Sold 300M iPods, Currently Holds 78% of the Music Player Market,” October 4, 2011, thenextweb.com.

- 4. Linda Tucci, “Business Process Reengineering (BPR),” February 2018, https://searchcio.techtarget.com/definition/business-process-reengineering.