THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION AND THE PERFORMING ARTS

Nothing in recent years has had a more profound impact on the performing arts world than the digital revolution. This phrase actually captures two revolutionary changes, one that is benign and one that is very problematic for the performing arts. We think it is worthwhile to review the major changes in recording technology over the last two decades, since one of the intended audiences for this book is recent college and conservatory graduates who did not experience these changes firsthand. We can’t tell you what the technological media landscape will look like in the future, but we can at least arm you with knowledge about how it came to look the way it currently does.

The first revolution is the representation of sound by on-off bits rather than analog signals. Vinyl records and magnetic tape are analog media, meaning the intensity of sound is represented by variations in the surface of grooves (records) or variations in magnetic field strength (tape). An analog sound signal is sampled and converted to a pattern of ones and zeros that a laser burns onto a disc. The pattern must be converted back to analog waveforms for sound reproduction.

Compact discs are digital media. The fidelity of digital recordings can be either less or more than that of analog recordings, depending on the sampling rate and the compression ratio. But regardless of fidelity level, digital recordings have no noise like record scratches or tape hiss. Compact discs and disc players require far less physical space to store a given amount of music than LPs or cassette tapes. In turn, solid-state storage formats—flash memory, in particular—have soared in capacity and plummeted in price, rendering compact discs all but obsolete. Thus, an eight-gigabyte thumb drive, sufficient for hundreds of hours of music, is now utterly commonplace. Not long ago, disk drives the size of a washing machine, costing as much as a luxury car, stored about 5 percent of that amount.

The other aspect of the digital revolution is the one we want to focus on, and it is a big problem for the performing arts: the ease with which digital recordings can be copied and distributed. The recording and distribution of sound and moving images no longer requires the distribution and creation of relatively scarce physical objects, and it no longer generates the corresponding value people tend to associate with such objects. What would it take to copy a vinyl LP, for example? You would need expensive, specialized equipment to capture the sound and burn it (in analog form) onto a master disc, which could be used to press copies in vinyl—unthinkable for the average person. In contrast, digital recordings are just a particular kind of computer file encoded according to a particular protocol such as MP3. The high bandwidth (transmission speed) that is available to most of us at very low cost makes it easy to share audio and video files.

At first, greater bandwidth made it possible for users to pass around copies of their music files to their online friends. Young people in particular quickly learned how to “rip” music files from compact discs, and while these files were too large to be sent as email attachments, specialized services soon arose to facilitate sharing. For a time, the leading sharing service was Napster, which appeared in 1999.

To use Napster, you had only to install a piece of software on your personal computer. Users could upload their own music files and download files provided by others. At its peak, there were about 80 million registered Napster users. A great many of them were college students, and many colleges found their campus networks choked with this traffic. Some chose to block Napster and similar services from their campuses not only because of concerns about bandwidth saturation but also because of copyright issues. But individual users seldom felt any qualms about sharing music files, particularly if they had already bought a piece on CD or were searching for a title that was hard to find or perhaps bootlegged. Some simply scoffed at the very idea of having ownership of songs or performances. Their slogan was “Information wants to be free.”

The recording industry, represented by the Recording Industry Association of America, was not amused. Neither were some major rock groups who saw their new songs spread around the Internet even before their official release. Several lawsuits were filed, and Napster was shut down in 2001, just two years after its inception.

That same year saw the debut of Apple’s iPod and the associated iTunes software. Neither the hardware nor the software was the first of its kind, but as with most of its products, Apple’s packaging and promotion were uniquely appealing to consumers. CEO Steve Jobs was successful in designing a system that was at first resisted by recording companies and artists but was eventually accepted. Consumers liked the choice of buying “songs” one at a time for 99 cents rather than having to buy a whole album for $12 or more. (“Song” has become the term that denotes a unit of music, an annoyance to those of us whose tastes run to instrumental music. Beethoven’s symphonies do not consist of four “songs” pasted together.)

There is currently a movement away from storage of files on one’s own devices to storage in “the cloud.” This term refers to storage or computing services provided by large organizations and accessed by customers—both businesses and individuals—via the Internet. The term comes from the fact that users seldom have any idea where their files are physically located; they might as well be off on a cloud somewhere. Cloud services are increasingly attractive to individuals because all the files they create on one of their devices (computer, tablet, smartphone) are immediately available on all their other devices and they need not worry about making backup copies or keeping track of what is current. The cloud trend has induced media consumers to move away from downloading content in favor of streaming it directly over the Internet.

The major music streaming services at this writing are iTunes, Spotify, and Pandora. On iTunes, you are allowed to purchase “songs” for 99 cents (sometimes $1.29); they are then stored on your device and, depending on your settings, in the cloud. Spotify and Pandora are streaming services. For a flat fee (and/or willingness to endure commercial messages), you acquire the right to listen to “songs” that are kept in the cloud, not on your device. To counter this, iTunes introduced a streaming service called iTunes Radio.

These services also make classical music available, and the number of offerings is substantial even though the pop offerings are much larger. A search on Spotify for Shostakovich, for example, turned up a “playlist” of essentially his entire catalog of published works. It behooves young classical musicians to get their work posted on these services. Rubbing shoulders, at least digitally, with the likes of Shostakovich is not a bad prospect at all.

COPYRIGHT LAW AND THE DIGITAL AGE

The digital revolution has raised fundamental questions about the rationale and practice of copyright law and patent law. The U.S. Constitution authorizes exclusive limited-time rights to authors and inventors “to promote the progress of science and useful arts.” But there is a downside to the presumed benefits of copyright law. Copyright holders have a monopoly on their work, and if they choose to sell their products, holders of monopolies can generally charge more. It remains an open question as to whether the social benefit from increased production engendered by copyright law outweighs the harm done by monopoly prices.

When you buy a copyrighted book, you are entitled to read it, sell it, give it away, or burn it. But you may not copy it, although you may quote brief passages under the “fair use” doctrine. You may also create parodies. Similar rights and restrictions apply to music and video recordings. But in the past—even after photocopy machines and cassette tape decks appeared—copying was usually more trouble than it was worth. However, now that so much content is in digital form and Internet access is cheap and nearly universal, that is no longer true. The digital revolution has laid bare the real reason why people refrained from making illegal copies of copyrighted works in the past: not so much out of respect for the laws or even for the creators whom the laws protected, but rather because of the sheer impracticality of making such copies. Many of us make copies of copyrighted material from time to time, knowingly or not. When we do it knowingly, we may rationalize our action by telling ourselves that we’re not imposing costs on anyone or depriving them of any property because when we copy a file, the original remains in its owner’s possession. And the facts show that many copies are being made. An organization called Tru Optik estimates that 10 billion files, including movies, television shows, and games, were downloaded in just the second quarter of 2014. Tru Optik further estimates that 94 percent of these downloads were illegal.1

It’s important to remember that when we talk about copyright law, we’re not talking about something that should regulate your creative life but only the commercial application of it. Take fan fiction, for example. Readers are completely free to reimagine their favorite literary characters in stories of their own making, just as musicians are free to play or modify anybody’s music they want. It’s the selling of material that draws on the creative work done by others that copyright law is concerned with. It’s important to remember that your creative life can and should be boundless. Just be careful about how it intersects with the commercial part of your career.

THE FINANCES OF THE PERFORMING ARTS IN THE DIGITAL AGE

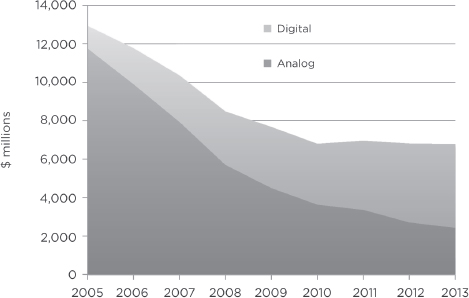

The profound financial effect of the digital revolution on the recording industry can be seen in Figure 4-1. Since just 2005, total revenues have fallen from about $13 billion per year, of which a small fraction was digital, to under $8 billion in 2013, of which the majority was digital. Total revenues have remained steady since 2010, disregarding inflation.

Not shown in these figures is the proportion of revenues that goes to artists. To be sure, in the old days of sales via physical media, many artists were unhappy with what they saw as the arrogance of recording industry executives and the seemingly arbitrary way in which favored artists were promoted. But at least the chosen artists did get a fairly good cut of revenues. Now, artists often receive a smaller slice of an ever smaller pie. In addition, recording companies are loath to invest in unproven or difficult-to-classify new talent because of the increasingly uncertain prospect that they would ever recoup such investments. Smaller companies may be more willing to try new talent, but they typically lack the resources to promote them vigorously.

Figure 4-1. The impact of the digital revolution on recording industry revenues.

A number of popular artists have simply given up on recording revenues as a significant income source. (We have had students who made only a few thousand dollars during a time when their material was downloaded hundreds of thousands of times.) Instead, they have come to view audio and video recordings as promotional material or loss leaders. They hope their recordings will build a following that pays off when they become famous and can attract audiences to live concerts. (And conversely, successful live performances can attract producers.) Groups can put together a music video using cheap recording equipment and readily available editing software. But the odds against them are staggering. While there is no harm in dreaming of fame and fortune, groups should view such projects as fun learning experiences and ways to further their mastery and enjoyment of their chosen art form.

The digital revolution has not spared the world of classical music. Like consumers of popular media, classical music buffs are blessed with an abundance of recordings available at little or no cost. Correspondingly, revenues from recordings have plummeted. A key question going forward is whether classical organizations can succeed with a path like their popular music colleagues are pursuing. Will widespread low-cost availability of recordings spur new interest in concert attendance and philanthropic revenue?

As a case in point, consider the music of the 20th-century Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whom some call the Beethoven of his time. His Fifth Symphony is his most popular. The definitive recording of the Fifth, many people believe, was made in 1959 by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. (The performance was broadcast live on commercial television, which seems unthinkable in this era of media companies focused on the next quarter’s earnings. Praise be to public television for its Great Performances series!) We found this recording of the Fifth offered on Amazon.com for $13 (CD), $8 (MP3 download), or—surprise!—$13 (cassette) or $13 (vinyl LP). We also found at least a dozen complete performances of the Fifth offered free on YouTube, including those led by legendary conductors Leopold Stokowski (1964) and Mstislav Rostropovich (1985) in addition to Bernstein, as well as countless uploads of individual movements. The YouTube offerings are low-fidelity, but that would matter little to a connoisseur intent on comparing interpretations.

CLIMBING TO THE TOP IN THE DIGITAL AGE

Among audiences for popular music, and to a lesser extent in the classical realm, there is a strong feedback effect that results in what Professor Luis Cabral of New York University calls a “winner take all” market.2 Fans like a particular performer or a particular song largely because their friends like it or they hear it a lot. Popularity begets popularity. Many performers aim to ride this spiral of fame and fortune; few succeed. Those who do succeed get the lion’s share, if not literally all the rewards.

This is not a new phenomenon. In the days of Top 40 Radio, starting in about 1955, airplay was the deciding factor in the success of a popular song. As audiences heard a song more often, disk jockeys would play it more, until a point of saturation was reached and it became the next big hit. The process showered handsome rewards on the few artists and producers who made hits this way. Recording companies were keenly aware of the advantages to be gained by getting disk jockeys to play their material (mainly three-minute sides of a 45 RPM disc), in hopes of beginning a spiral of success—so much so that they began to quietly offer payments to DJs to play their records. This practice, a clear conflict of interest, became known as payola. It burst into the open in 1959 and prompted congressional hearings. Alan Freed, the disk jockey who is said to have coined the term “rock and roll,” was caught up in the scandal, as was Dick Clark, a prominent television figure of the time whose early career was almost ruined.3

Top 40 Radio no longer dominates popular music to the extent it once did. Recording artists no longer care so much about radio air time. Facebook “likes” are the new currency. Likes beget likes in a spiral reminiscent of Top 40 Radio. Because likes are so valuable, many people now offer to generate them for a fee. One way to do this is through advertising. A shadier practice is an echo of payola in which likes can be purchased at websites such as Boostlikes.com. Some of these providers offer likes for as little as a half cent each. This new “industry” generates an estimated $200 million in annual revenue in Facebook likes alone, not counting sidelines such as the manufacturing of Twitter followers, LinkedIn connections, and video views. The work is usually outsourced to offshore “click farms” where workers click away all day for as little as a dollar per thousand clicks.4

The foregoing discussion is from the world of popular culture, but the same phenomena can be seen in the classical world, albeit in a more subdued form. Yo-Yo Ma is today’s best known cellist; who is second? The Three Tenors were Pavarotti, Domingo, and . . . who? Even in the classical performing arts, it’s largely a winner-takes-all game.

MARKETING

MARKETING

Ralph Waldo Emerson supposedly said, “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door.” One of the core messages of this book is that, in this instance, Emerson was dead wrong. To the person who makes the best mousetraps in the world but never bothers to tell anybody, we say, “We hope you have another way of supporting yourself than selling mousetraps.” No matter how high the quality of any good or service, it won’t be profitable unless people know about it. Without marketing, work can have no commercial value.

Most basically understood, marketing is all the activity that gets a finished product from its place of manufacture into the hands of those who would buy it. It is the process that gets a product to market. Within organizations, marketing is sometimes considered a soft or secondary concern, but without it no business would survive, even those that depend on philanthropic support.

In the performing arts, marketing fills the space between the end of the creative process and the experience of the audience. It’s everything that happens from the end of the last rehearsal to the rising of the curtain on opening night.

If you think that the arts are inherently above marketing, just imagine a book without a reader, music without a listener, or a dance performance for nobody. The individual satisfaction of the author or performer matters deeply, but so does the continuance of our great art forms and the joy and sense of meaning that audiences derive from them. Great art deserves as wide an audience as possible. Creating that audience is the mission of the marketing process.

If you’re worried that you might not have the temperament for self-promotion, remember that you have a huge advantage over professional advertisers and marketers in the for-profit world. You know your product better and care about it more deeply than they do about their products because your product is yourself. It is the years you’ve devoted to mastering a difficult skill, one that is essential to the meaning of your life. Don’t think of marketing as an insincere prelude to taking people’s money. Think of it instead as a way to connect a desire for art with the ability to satisfy that desire. Rather than feeling that your art is somehow cheapened through the marketing process, consider instead that the huge amount of your life that your art has consumed deserves to be honored by as many people as possible.

Core parts of any marketing plan include:

- •Market research. Who wants your product, and how much might they be willing to pay for it? This includes potential donors as well as paying ticket holders.

- •Branding. What makes your product different from other, similar products, and how can you convey that in a brief and powerful way? Having a strong brand is the first step to cultivating an audience with a strong relationship to the art you make.

- •Advertising. How can you project awareness of your product and create a demand for it or tap into existing demand for similar products?

- •Delivery. What’s your plan for the delivery of your product to its consumers? In the case of the performing arts, delivery can take the form of live performance, recordings, streaming Web content, or some as yet unknown combination of all three. Knowing what the finished product will be like can help you create specific demand for it in your audience.

THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY IN THE DIGITAL AGE

As we saw in Chapter 3, symphonies and opera companies are fighting for their very existence in the face of declining attendance, aging audiences, and shaky support from foundations and governments. Clearly, these organizations must speak to potential audiences that are younger and more diverse, and they must speak to them in their language. Here is how one organization, the San Francisco Symphony, is doing that.

The Symphony maintains an attractive and functional website at sfsymphony.org. The site offers schedules, online ticket purchases, travel and parking information, and the like. But these sorts of online conveniences are the norm these days—the minimum one would expect. The website also shows that the Symphony is trying hard to reach beyond its traditional audiences, who are disproportionately older, white, and affluent (as discussed in Chapter 3). These potential audiences include the young techies who have become so conspicuous in San Francisco, but also people of Hispanic, African-American, and Asian descent who may never have heard classical music, not even in a recording. A First Timer’s Guide page begins at the beginning: “What is classical music?” An answer in the form of a short paragraph is given, as well as a 20-minute video by the Symphony’s music director, Michael Tilson Thomas, widely known as MTT. In a TED Talk video,5 MTT is seated at a piano, casually dressed, and speaking in a conversational tone. He tells how his father influenced his career. He shows how music evokes varying emotions, explaining the very basic concept of major versus minor chords. He illustrates the dramatic transition from despair to joy in the third movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. He concludes with a personal story that is worth paraphrasing here.

While visiting a relative in a nursing home, MTT spied a very shaky old man shuffling across the room with a walker. The man sat at a piano and plunked out a few notes while muttering, “boy . . . symphony . . . Beethoven.” MTT went to the piano and said, “Friend, by any chance are you trying to play this?” and he began playing a passage from Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. The old man’s eyes widened: “Yes, yes!” he said. “I was a little boy. It was a concerto! Isaac Stern!” MTT marveled that after most of this man’s mind had been lost to dementia, the memory of this music remained. “That’s why I take every performance so seriously, why it matters so much,” says MTT. “I never know who might be there, who might be absorbing it, what will happen to it in their life.”

Tilson Thomas is optimistic. “Now I’m excited that there’s more possibility than ever in sharing this music,” he says, citing the YouTube Symphony Orchestra as one example. Young players from all over the world submitted audition videos online, and those who were chosen were invited to come to New York to assemble as an orchestra and perform in 2009. A repeat event in 2011 was held in Sydney, Australia, and was streamed online to more than 30 million viewers.

A BALLERINA IN THE DIGITAL AGE

Petra Conti is a rising star in the world of ballet. Born in Italy in 1988, she graduated from the National Academy of Dance in Rome at age 18 and thereafter rose quickly through the ranks of Italian ballet. She joined the La Scala Ballet of Milan in 2009 and was promoted to principal dancer in 2011. In 2013, she moved to the Boston Ballet, where she and her husband were, as of 2015, both principal dancers.

Petra belongs to the millennial generation and has grown up in the digital age. This is the generation for whom instant communication, digital media, and social networking are as water to fish. As one would expect, Petra is Internet-savvy and has a website (www.petraconti.it) that provides her biography, photos, videos, and press clippings. There is also a promotional link to a women’s fashion designer whose creations she wears in one of her videos. Most of the site is in English, the primary language of the Internet.

Petra’s website is not unusual; most featured performers have one. We mention hers as an example that illustrates the opportunities that the Internet provides to performers that would have been unthinkable to 20th-century ballerinas such as the legendary Galina Ulanova (1910– 1998). Mme. Ulanova was both a beneficiary and a victim of the Soviet system—a beneficiary in that she gained the attention of Joseph Stalin, who gave her a position at the Bolshoi Ballet, and a victim in that she was not allowed to travel abroad until rather late in her career. Although some of her performances were recorded on film and she may have appeared on Russian television, her opportunities for career advancement were severely limited, not just by the strictures of the Soviet system but by the lack of anything like the communications opportunities that are open to Petra Conti and millennial performers like her. Almost anybody in the world can go online today and learn about Petra Conti, and given a broadband connection, anybody can watch her dance. The Internet will doubtless be the primary vehicle for spreading her fame. Her Web presence may also provide her with further commercial opportunities like the aforementioned link to the fashion designer.

KEY NOTES

KEY NOTES

Questions to Ask Yourself

- •Are there digital distribution hubs that I can use to disseminate my music or videos of my performances? (These can be blogs, huge commercial sites like iTunes, social media sites, or ways of connecting that are yet to be invented.)

- •In an age of easily duplicated and distributed media, is there a new, more important role for live performance? Are there ways I can incorporate this into my business plan?

Tips

- •Don’t waste time and energy trying to predict the future of digital media technology. Nobody can do that—not even the biggest players in the business. But don’t disconnect from changes in the tech landscape. Do your best to keep up and take advantage of the tools your peer group is currently using and paying attention to, but don’t waste time being anxious about change.

- •Don’t spend too much time trying to find the perfect formula for social media success. There is no formula. Musician Laurel Halo gives the best piece of advice we’ve heard about social media ever: Be yourself. Social media are no different from any other media. They are a way of expressing who you are to people en masse. People won’t follow you because of gimmicks. They’ll follow you because they love your art and are interested in keeping up with your career. Do be sure to give out plenty of info about where people can get tickets to your next show or buy your next recording, but resist the urge to use your social media platform solely to advertise. That is a surefire turnoff. Give people a window into your life and steady access to your work, and you will keep them interested.

- •Just like almost every other aspect of your work, maintaining an online presence will probably work out best if you are open to collaborating with others. You might be able to maintain a Twitter feed on your own, but making a YouTube video, for example, takes a team effort. Tap into your network of friends with needed skills to make the most of your online presence.

- •Feedback is a simultaneous disadvantage and advantage to having a Web presence. There is a lot of negative chatter on the Web, and the more you put yourself out there, the likelier it is that some of it will come your way. Try not to take it personally. Take advantage of any positive feedback, and encourage your growing network of supporters. Be sure to take advantage of that rarest type of feedback: constructive criticism. And don’t take it personally if you’re not getting as much activity back as you’re putting into the Web. We’ve seen tweets and Facebook posts from huge stars generate almost no activity at all, while posts from unknowns go viral overnight. Like so much of your working life, success is sometimes a matter of chance. The important thing to remember is that everybody is expected to have an online presence, so keep plugging away at it.

Exercises

- •Pick a few performing artists whose work you admire, and take a look at how they use technology. Look at their Web presence, and try to find out as much as you can about the digital distribution of their work and how that affects their revenue streams. For famous performing artists, this information is likely to be available as news articles on the Web. If you can’t find any of this information about less famous performing artists, don’t be afraid to contact them directly! If you don’t know which performers to pick, start with the ones we profile in Chapter 7. Pay attention as well to how they use the Web to promote themselves and express who they are. Use what you find successful about their work to spark ideas for your own.