READING AND UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Some people, perhaps artists in particular, think accounting is the most boring subject in the world. You may be one of these people, and you may be tempted to skip this chapter. We hope you won’t, though, because a little accounting knowledge can serve you very well. Why? Without modern double-entry bookkeeping, all businesses— including nonprofits—would grind to a halt. Management would be at sea if an organization didn’t have accounts to show whether it was on a path toward prosperity or oblivion. You may never be a manager but you should have some understanding of your organization’s financial health. The great German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe understood this very well. He called double-entry bookkeeping, which we are about to describe, “among the finest inventions of mankind.”1

Basic accounting—or bookkeeping, if you will—isn’t all that difficult. After you complete this chapter, you will know the basic bookkeeping concepts that all businesses, nonprofits, and governments use. To be sure, accounting can get extraordinarily complicated because there are situations where it is very difficult to know how to categorize some items, how to estimate their market value, or whether a particular expense should be carried into the future. That’s why some people work very hard to become certified public accountants and why they usually earn big salaries. We won’t be concerned with accounting complexities, just the basics.

JUDY’S PERSONAL FINANCES

Here is a simple bookkeeping exercise that will take us lightly through all the categories. It concerns the personal finances of Judy, a hypothetical dancer. Even though individuals and households don’t generally do accounting like organizations, it will be instructive for us to do so here.

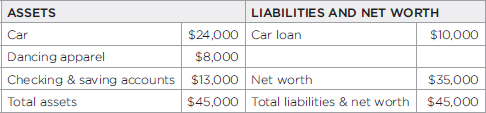

We start with a snapshot of Judy’s assets (what she owns), liabilities (what she owes), and net worth (assets minus liabilities). We track income and expenses over the course of a year, and then take another snapshot at the end of the year. (Incidentally, accounting years, called fiscal years, can start on any date, not just January 1.) Let’s say Judy’s financial situation at the beginning of the year is as follows:

- •Assets (what she owns): $45,000

- •Liabilities (what she owes): $10,000

- •Net worth (assets minus liabilities): $35,000

What do we count as assets? Only things that are durable (they don’t wear out too quickly), tangible (you can drop them on your foot), and marketable (they have a dollar value that can at least be estimated). (Note that corporations sometimes list intangible assets, called goodwill. We are not considering this category here.) Judy’s most valuable asset is her dancing skill, but because it is well-nigh impossible to attach a dollar figure to this asset, it is intangible and we don’t include it in her accounts. To keep things simple, we’ll ignore assets like a laptop, cell phone, etc., and assume Judy has only the three following assets, whose total value is $45,000:

- 1. Car: $24,000

- 2. Dancing apparel: $8,000

- 3. Checking and savings accounts: $13,000

Why do we include her dancing clothes as an asset but not her street clothes? Because dancing apparel is crucial to her livelihood, as are her car and her bank accounts, while her street clothes are not. We want to emphasize those assets that directly support her professional life.

Judy has just one liability, a car loan whose current balance (principal) stands at $10,000. If she had signed a long-term lease on her apartment, we might count that as a liability, but we’ll assume she’s renting month-to-month.

During the course of the year, Judy earns $85,000 (which we call her gross income) from dancing gigs, teaching, and a little interest on her savings. (As this was written, banks are paying little or no interest. Our point here is that income from bank accounts or investments is a category of income that should be recognized.) She spends $82,000 on living expenses: rent, food, clothing, transportation (mainly her car payment), etc. She has a $3,000 surplus of income over expenses (which we call her net income) for the year and she is left in the following position:

- •Assets: $42,000

- •Liabilities: $8,000

- •Net worth: $34,000

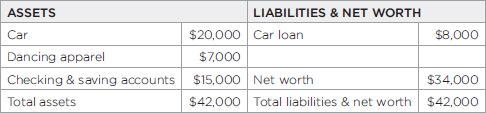

You may notice something strange here. Even though she saved $3,000, her net worth fell over the year by $1,000. How can this be? The answer lies in changes in the value of her assets and liabilities. Depreciation is one such change. This is the loss in value that assets suffer as they wear out. Her car depreciated to $20,000, a loss of $4,000. Although she replaced some dancing apparel, its total value fell to $7,000, a loss of $1,000. On the plus side, Judy added to her assets by increasing her bank balance by $2,000, to $15,000. Finally, she reduced her liabilities by paying down her car loan from $10,000 to $8,000. That leaves her assets and liabilities at:

- •Assets: $20,000 + $7,000 + $15,000 = $42,000

- •Liabilities: $8,000

- •Net worth: $42,000 – $8,000 = $34,000

So we see that even though she enjoyed an earnings surplus, she suffered a slight drop in net worth due mainly to depreciation.

Now let’s arrange these numbers in the conventional form that dates back several centuries: the T-account. We show assets in the lefthand column and liabilities and net worth in the right-hand column. Both columns are added, and the sums must always be the same. The books must always balance.

For the beginning of the year we have:

You can think of net worth as the number that has to be added to liabilities to make the bottom lines match.

We have seen that of Judy’s $85,000 income for the year, she spent $82,000 on ordinary living expenses, paid down her car loan by $2,000, and increased her bank balance by $2,000. Her car depreciated by $4,000 and her dancing apparel by $1,000. These amounts left Judy with the following balance sheet for the end of the year:

Again, we see that even though Judy managed to spend $3,000 less than she took in, her net worth dropped by $1,000 due to $5,000 depreciation offset by a $2,000 bank balance plus a $2,000 car loan reduction.

Now, changing the story a bit, let’s say Judy had bought a new car for $32,000, using $5,000 from her savings and a $27,000 car loan (ouch!), while selling her used car for $12,000 and paying off its remaining $8,000 loan balance. (Notice that the $20,000 estimated car value in her balance sheet was way too optimistic since she got only $12,000 for it. Such things happen.) We would record the following income and expense items:

- •Income: $12,000 from used car sale

- •Expense: pay off $8,000 car loan

- •Expense: $5,000 new car down payment

Here’s an exercise for you: Construct Judy’s balance sheet after completion of this transaction.

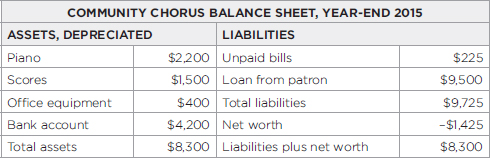

THE FINANCES OF A COMMUNITY CHORUS

We now look at the finances of a hypothetical community chorus. Community choruses are a popular outlet for people who love music and have some talent but make their living in other ways. Some choruses are affiliated with colleges or churches, and some are stand-alone. Even with modest expenses, it is all but impossible for a community chorus to get by on ticket sales alone.

A typical chorus needs a conductor, scores, a rehearsal accompanist, a place to rehearse, and a performance venue. While most choristers are volunteers and in fact may be expected to donate money, larger groups sometimes employ ringers, a few paid choristers who may act as section leaders. Conducting a chorus of any size is too much to expect of a volunteer. A conductor who has the requisite background and can devote sufficient time to the job (performing, rehearsing, auditioning, learning scores, courting donors) must be paid. The same is often true of rehearsal accompanists. The larger outfits may need a paid administrator as well. There could also be advertising expenses, hall rental fees, and travel expenses.

Expenses may not end there. Suppose, for example, a group is ambitious enough to stage Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, a popular and very demanding piece. Like all major choral works, Carmina includes prominent solo parts. Sometimes a chorister is good enough to step into a solo role, but the solo parts in Carmina are quite challenging and in fact call for that rare bird, a countertenor. Paid soloists are very desirable for this piece, although advanced voice students can sometimes be had for little or no compensation.

To do the piece justice, the chorus must employ a full orchestra. For some works, a piano transcription makes an acceptable substitute for an orchestra, but not for Carmina Burana, whose movements run the gamut from subtle lyricism to blasting horns. Again, amateurs may be available, but at least the key parts like the concertmaster or the oboe or horn players should be professionals. Sometimes the Musicians’ Union will cooperate and waive the usual union pay scale.

A typical community chorus would have very little in the way of assets or liabilities. It might be allowed free use of rehearsal and performance spaces or it might rent them, but it would not own them. It might own a piano and perhaps a collection of scores, though choristers are often asked to buy their own scores. The chorus’s principal asset would probably be a bank balance. It might have borrowed money and might have deferred expenses, but otherwise there would be very little to count as liabilities.

Thus, the finances of a community chorus would pretty much be a matter of cash flow. It would have to keep enough cash on hand to allow for uncertain ticket receipts in addition to recurring expenses. Fundraising would have to be a top priority. While smaller groups may resort to bake sales and such, a larger group would be wise to cultivate a permanent sponsor. For example, a local bank or the local electric utility might see sponsorship as a way to burnish its image with the local populace. The company’s logo could be featured prominently on the chorus’s printed materials and website.

Here is the year-end balance sheet of our make-believe chorus.

Notice that the chorus has a negative net worth and is technically insolvent. The patron who made the loan is probably worried but not inclined to press the chorus into bankruptcy.

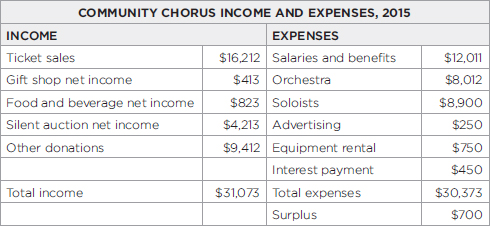

We now look at income and expenses for our chorus, summed over the year 2015.

The chorus earned a small surplus (profit) of $700 for the year.

TWO KINDS OF FINANCIAL DISTRESS

There are two basic ways an organization can get in financial trouble, be it a for-profit company, a nonprofit, a government, or a household. The less serious problem is called illiquidity, a situation where there is not enough cash to pay bills coming due. Assuming the organization has sufficient noncash assets, this problem can usually be remedied by borrowing against those assets, by selling some of them, or by quickly generating more income. A onetime liquidity crunch may not be very serious, but a series of such crunches can lead to the more serious problem of insolvency. This occurs when an organization’s liabilities exceed its assets. At this stage, management’s options are limited. Creditors (those to whom the organization owes money) may force the organization into bankruptcy, which may be followed by restructuring of its obligations or liquidation—in other words, termination of the organization. Of course, management can appeal to creditors to refrain from pushing for bankruptcy and to patrons for emergency donations. If you find yourself under serious pressure from creditors and truly unable to pay the bills without going under, know that the status of your organization as a not-for-profit and an arts organization can help you survive. While we’re not at all advocating taking advantage of anybody’s good faith, it’s okay to remind your creditors that you’re not in business to make a profit but to contribute to your community, and you can ask for leniency.

Because liquidity (availability of cash to meet current obligations) is important, any organization, whether for-profit or not, must keep a close eye on cash flow. As the term implies, this category tracks the cash coming in minus the cash going out during some time period such as a quarter or a fiscal year. Cash flow is not the same as profit, which is earnings minus expenses. One difference is that some kinds of incoming cash do not count as earnings. Examples are proceeds from sales of assets, money borrowed from a bank, or proceeds of sales of securities (shares of stock or bonds). Likewise, some kinds of outgoing cash do not count as expenses. Examples include purchases of durable equipment that is depreciated over time, payment of interest to bondholders, or payment of dividends to shareholders.

Notwithstanding her reduced net worth at year end, Judy’s cash situation is solid. She enjoyed a $3,000 positive cash flow during the year and ended up with $15,000 in the bank. She would be able to weather a short-term slowdown in her income with little difficulty.

As the community chorus example shows, nonprofit organizations can and do earn profits, although “surplus” is the more common term. While profits are not their primary mission, competent managers of nonprofits keep an eye on the bottom line so as to avoid excessive or extended losses. If you are considering joining an arts organization, you should pay attention to its finances. You want some assurance that the group will remain in business for the near future, at least. Has it been losing money? How has it made up losses?

FINANCIAL REPORTS

All publicly held for-profit corporations are required to issue reports of their financial situation. They publish quarterly and annual reports and file various forms with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which are available to anyone. Their tax returns, however, are generally not made public.

Nonprofit reporting requirements are a little different. Excepting religious institutions, most nonprofits must file Internal Revenue Service Form 990, which is supposed to justify continuation of their tax-exempt status. These forms can be found on websites like www.guidestar.org.

THE PROSPERITY OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY

We retrieved Form 990 for the year 2011 for the San Francisco Symphony. It is 53 pages long, although many pages are blank because they are not applicable to the Symphony. The very first entry shows the Symphony’s mission statement: “Enriches, serves, and shapes cultural life throughout the spectrum of Bay Area communities.”

Performers and audiences alike naturally prefer to focus on the music, not finances. But as we stress throughout this book, both performers and audiences need to pay some attention to financial matters. Over the last 40 years, the San Francisco Symphony has advanced greatly on several fronts. The quality of the performers and the music has improved, the Symphony moved to a hall of its own, its reputation has spread, and although there have been rough patches, including a couple of musicians’ strikes, its finances have generally been stable.

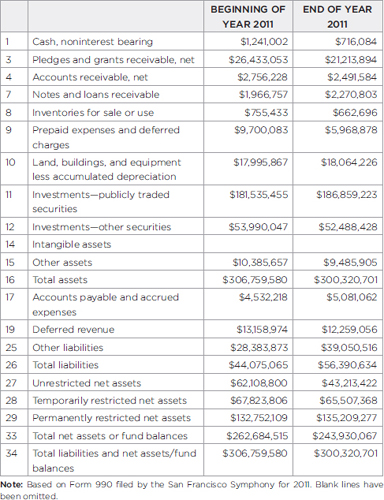

Figure 5-1 shows the Symphony’s balance sheet for 2011, taken from its Form 990. The first thing to note for any balance sheet is how the numbers are expressed. The Symphony’s numbers are expressed in whole dollars, but large corporations sometimes present numbers in thousands or even millions of dollars so as to reduce clutter.

Figure 5-1. A San Francisco Symphony balance sheet.

Line 1 shows $1.2 million cash on hand. Since the Symphony spends about $78 million per year (as shown in Figure 5-3 on page 76), that was enough cash to pay only about 1.5 weeks’ worth of expenses. However, a balance sheet is a snapshot, and it’s possible this figure was a lot higher at other times during 2011. If it got much lower, the Symphony could have a liquidity problem, i.e., a cash crunch.

Line 3 indicates donor pledges that have been made but have not yet been paid. Some of these promises may not be kept. If this was a bank, we would see allowances for doubtful loan repayments, but nonprofits usually do not attempt to make any such estimates with regard to pledges.

When an organization pays a bill like an insurance premium that covers the year ahead, it is called a prepaid expense. The payment has been made but most of the benefit (the insurance coverage) still lies ahead. The excess is counted as an asset and marked down as the year goes by. Unpaid bills are the opposite; they would be subtracted from any prepaid expense (see Line 9).

The city of San Francisco owns Davies Symphony Hall, where the Symphony performs, so its value is not an asset of the Symphony. The Symphony does own many kinds of equipment, which are depreciating assets. Also, the Symphony has paid for improvements to Davies Hall that are counted as assets; they are depreciated as the time approaches when they may need to be redone. The amount shown on Line 10 is the result of subtracting about $16 million worth of depreciation from original costs of about $34 million for those assets.

Depreciation can be a tricky business. Accountants assign useful lives to assets and then write them down (reduce their stated value) every year. An ordinary desk may be assigned a ten-year life, yet it remains perfectly serviceable for decades, but the accounting rules say it has no value once it reaches age ten. In contrast, a laptop computer may be assigned a three-year life, but after just two years—at which time its stated value is one-third of its purchase price—it may be discarded in favor of a tablet. Income is generated when an asset is sold for more than the depreciated value on its balance. Expense is incurred if it is sold for less—as when Judy sold her car for $12,000 even though its estimated value had been $20,000.

Most nonprofits of medium or large size have an endowment—a portfolio of income-producing assets. Donors can generally specify whether their contributions are to be used for immediate expenses or are to be added to the endowment. Harvard University has a whopping $32 billion endowment that is managed by a highly compensated professional team. The endowment income provides major support to the university’s operations. Organizations generally spend only the income from their endowments, not the principal. However, they sometimes “invade” their endowments, spending some of the principal. They may say they are borrowing from their endowment, but whether they do or not, invasion of endowment principal generally suggests desperation.

The San Francisco Symphony has an endowment, most of which is invested in publicly traded securities (probably stocks and bonds, Line 11) and other securities that are not detailed (Line 12). Endowment income amounted to about $4.0 million in 2011, up from $3.2 million during the previous year but still down from the prerecession high of $5.3 million. This income is not a huge contributor to the Symphony’s annual income, but it can make a big difference at the margin of a good year or a bad year.

As we saw with Judy’s balance sheet, total assets (Line 16) must exactly equal the sum of total liabilities (Line 26) plus total net assets (Line 33), and they do (Line 34).

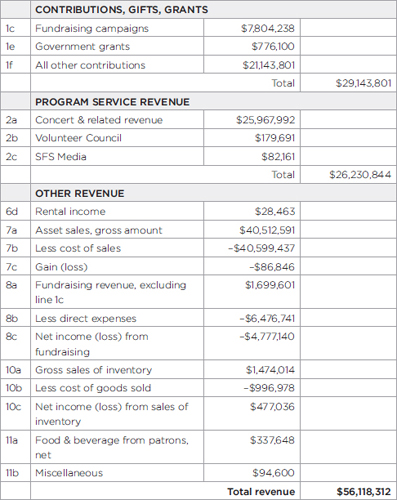

Figure 5-2 shows revenues earned in 2011. Right away, we see that contributions (Lines 1) amounted to more than half the Symphony’s revenue for 2011. In other words, ticket sales cover only about half of expenses, and this fact is made clear to subscribers, who are strongly urged to add a donation to the price of their tickets. Line 8 shows that fundraising expenses were a lot larger than the amount raised. There is probably an explanation for this—perhaps those expenses generated some funds that will be part of the income for future years. (If you were interviewing for a job with the Symphony, you might ask your interviewer about this. Although there is a risk that such a question might be viewed as impertinent, it would show that you have made some effort to understand the Symphony’s finances. Interviewers like job applicants to show they have done some homework.)

Figure 5-2. A San Francisco Symphony statement of income.

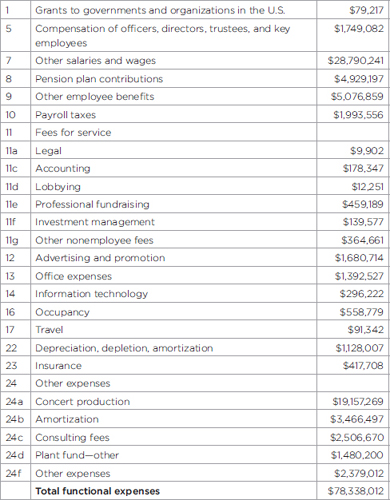

The Symphony’s management personnel are paid well. Although not shown in Figure 5-3 (expenses), elsewhere in Form 990 we find that Executive Director Brent Assink received $638,857 in total compensation during 2011, and Concertmaster Alexander Barantschik got $560,010. For some reason, the salary of music director Michael Tilson Thomas is not listed on Form 990, though a newspaper report put his pay at $1.6 million for 2008.2

Most businesses of medium to large size, and some small ones, offer employee retirement benefits as well as health insurance and other “perks.” There are two basic categories of retirement plans: (1) pensions, also called defined-benefit plans, and (2) defined-contribution plans, mainly 401(k) plans for businesses or the equivalent 403(b) for nonprofits. Pension plans provide retired employees with a certain monthly income for the rest of their lives, the amount of which is based on their salary and years of service. This is a risky proposition for the company because of uncertainty about when people will retire, how long they will live, and whether the assets in the pension plan will throw off sufficient income to cover obligations. Many government bodies and some corporations are in trouble because of under-funded pension liabilities. Except in special circumstances, organizations with pension plans must contribute something to their pension plans to keep them financially sound. The Symphony’s contribution for 2011 appears on Line 8 of Figure 5-3.

Pension plans are becoming less common in the business world because of the uncertainties just mentioned. Many companies have switched to defined-benefit plans in which the employer and employee each contribute to a fund that is invested, usually in stocks and bonds or mutual funds. Employees generally have some say as to which investments they want in their account. Upon retirement, an employee receives a lump sum, at which time the employer’s involvement ceases. The retiree decides whether and how to spend his retirement money, in accordance with tax laws. Most pension plans are found in unionized organizations such as the Symphony or in government agencies.

Figure 5-3. A San Francisco Symphony statement of expenses.

If you work for any kind of organization that offers retirement benefits, you should take full advantage of them if at all possible. This is especially true if your employer offers to match all or part of the contributions that you have taken from your salary, because matching funds are free money, pure and simple. With or without matching, the compounded value of retirement savings begun at an early age can be enormous when retirement comes.

THE DEMISE OF THE SAN JOSE REPERTORY THEATRE

The financial statements of the San Francisco Symphony present a picture of an organization in pretty good financial health. The San Jose Repertory Theatre was a very different story. After years of deficits and a bailout from the San Jose city government, the Rep closed its doors in 2014 and filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

This was an organization about a tenth the size of the Symphony. It had several advantages going for it: a talented group of resident actors and directors, live presentations, most of them produced by the Rep itself, and its own 584-seat theater located in the heart of downtown San Jose, California, a short distance from a major state university. San Jose is a city with a population of 1 million (6 million in the entire Bay Area), including abundant Silicon Valley wealth and talent. The city government was a major supporter, seeing the Rep as the centerpiece of its efforts to develop downtown San Jose as a cultural and entertainment attraction. Following the Rep’s demise, there was quite a bit of speculation about the causes of its failure. Many noted that the San Jose Symphony had been swept away by the dot-com bust of 2001, even given a talented conductor and a new Performing Arts Center. This suggests that San Jose, tech wealth notwithstanding, still lacks the critical mass of support needed to establish major cultural institutions. No doubt this is partly due to the magnetic pull of San Francisco, 50 miles north.

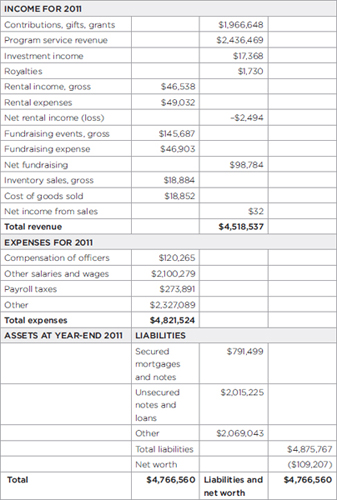

The Rep’s summary financials are shown in Figure 5-4. The income statement shows that ticket sales covered a little over half of expenses, which is fairly typical. Rental of its hall to outsiders actually resulted in a loss. One out of every three dollars received in fundraising events went to fundraising expenses, which is high. Sales of assets resulted in a gain of just $32, but that figure may be deceiving. As we have said, valuation of assets is tricky, and it may be that the items sold were no longer of any use to the Rep even though they had been assigned a value of $18,852. Repeating the pattern of previous years, the Rep sustained an operating loss of about $300,000 for the year. This left the company in a position of negative net worth: insolvency.

Figure 5-4. San Jose Repertory Theatre financials for 2011.

We have said that insolvency is a very serious matter, but we should qualify that a bit. For one thing, the accuracy of an insolvency verdict depends on whether assets are realistically valued. If it turns out that assets have been overvalued—as Judy’s car was prior to its sale—an organization’s net worth may turn negative, rendering it at least technically insolvent; of course, undervaluation of assets can have the opposite effect. An organization’s track record and future prospects are also important. If there is reason to believe that an insolvent organization’s financial embarrassment is temporary and that a turnaround is likely, creditors (those to whom money is owed, such as suppliers, bondholders, or employees) may decide to be patient. Otherwise, things can go wrong in a hurry. Bondholders may press for repayment and perhaps file involuntary bankruptcy proceedings—a last resort given hefty legal costs. Supporters may decide further donations would be wasted. Employees may refuse to take cuts in pay and benefits. All of these can trigger a death spiral. Such was the sad fate of the San Jose Repertory Theatre: The doors closed in 2014 as the Rep filed for bankruptcy. At this writing, it is not known what the city of San Jose will do with the empty theater. The city’s financial difficulties (particularly its pension liabilities) make it unlikely that anything new will open there soon.

HOW TO WRITE A BUSINESS PLAN

HOW TO WRITE A BUSINESS PLAN

Professionals in almost any field sooner or later find it necessary to write a proposal or business plan. Business schools teach this subject in depth, and we can only review it very briefly.

The most important key to writing a successful proposal, whether it is a grant proposal or a commercial business plan, is to put yourself in your readers’ shoes. Among other things, try to:

- •Understand your readers’ business so you can show them how you will help them fulfill their mission. Without saying so directly, lead your readers to believe that your work can make them look good to their boss or clients.

- •Be respectful of their time. Don’t send a proposal that does not fall within (or close to) the mission of your target organization. Write succinctly and directly, avoiding unnecessary jargon.

- •Where there are risks or uncertainties, do not try to hide them. Be candid and indicate as best you can how you propose to address these problems.

- •Put your best foot forward. However, do not exaggerate and do not feign qualifications that you don’t really have.

While there are no strict rules as to how a proposal should be organized, the following topics can be considered core elements:

- •The needs that drive your proposal and the benefits you believe will accrue from your work.

- •The strategies you have in mind and how you will implement them.

- •The basic purpose of your proposal. Even if you’re responding to a request for a proposal, where the readers know perfectly well what the purpose is, repeat it anyway to show you’re on the right track. State very briefly what you intend to accomplish and how.

- •The key individuals who will be involved in the work. Describe how their experience and education qualify them for the job.

- •Financial and budget information. Do not underestimate the start-up capital you will need. Allow for contingencies; expect unexpected expenses! You will find it harder to return to the well, should you run out of money, than to get enough at the beginning.

IN SUMMARY

We already said that for-profit organizations and nonprofits are very much alike in many respects. You probably wouldn’t know just from looking at the expenses in Figure 5-3 whether this entity was a forprofit or a nonprofit. On top of wages and salaries, you see benefits, payroll taxes (nonprofits must usually pay Social Security tax and disability tax), and contributions to the pension plan. The organization incurs the usual professional expenses as seen on Line 11: legal, accounting, investment management, etc. Investment management fees are, as one would hope, a fraction of 1 percent of assets. The organization advertises, pays an office staff, and uses computers (Lines 12, 13, and 14). It even shows a small lobbying expense (Line 11d), and it made donations to other nonprofits (Line 1). All of these expenses are typical of for-profit companies as well as nonprofits. A for-profit business, unlike a nonprofit, would also show income tax payments and possibly dividend payments to shareholders.

KEYNOTES

KEYNOTES

Questions to Ask Yourself

- •Do I know the financial health of the organizations where I am seeking work? (Getting a sense of the financial health of an organization where you are interviewing for a job is great for two reasons. First, it can help you determine if you’re likely to have a job in the future, and second, it can arm you with a great deal of knowledge that you can deploy in your job interview, if it seems appropriate. Knowing about the finances of the place you are interviewing sends a strong signal that you are thorough and care enough about the organization to learn more about it on your own time.)

- •Do I have a sense of my own financial health? Do I know which questions to ask to determine it? Am I afraid to ask these questions? (In writing this chapter, we’re not implying that you need the financial literacy of an accountant to be responsible about money, either your own or that of your organization. But we are saying that knowing how to ask and answer basic questions about money is an essential life skill.)

Tips

- •Any not-for-profit organization (most performing arts organizations fall into this category) has to file regular reports of its financial situation with the government. The reporting requirements for nonprofits are greater than they are for for-profits. These reports, as well as other valuable information, are available online at the websites of GuideStar, Charity Navigator, and the Foundation Center, among other organizations. When looking over financial reporting data, you will find a lot of terminology and forms of notation that may seem overwhelming or unfamiliar at first, but you’d be surprised how much of the information is relatively easy to understand if you stick with it even for just a few minutes. You will be able to find the mission statement of the organization in question, salaries of the highest paid employees, how much money the organization made in any given year, and footnotes explaining anything extraordinary, both good and bad, about the group’s financial situation.

- •Try to embrace the fun side of doing the numbers. Numbers can be like a puzzle that you get to figure out or a new language to learn that will get you further in the world. Don’t think of your finances as separate from your artistic dreams. Think of them as the building blocks of your dream.

- •If you are a student, look to see if there are any classes in entrepreneurship or business at your school. If there are no official business classes, go to your career services office or guidance counselor and ask if there are any resources you can tap into to start developing the business side of your career. If those resources aren’t available, find somebody on the faculty of your school or in your community whom you trust, and ask her about practical ways to develop your career. It’s never too late to get help, and it is always closer at hand than you think.

Exercises

- •Calculate your net worth the way we do for Judy in this chapter. Don’t worry about including an accounting of everything you own. Just start with the major items and see what you come up with. Try out this exercise periodically to see whether your net worth increases or decreases.

- •Take the table we provide for the finances of the community chorus in this chapter and try to fill in your own numbers (estimates are fine) for an existing arts organization. This is your first step toward knowing how to balance the books.

- •Follow the money. Pick an arts organization and find out how it is funded. It can be a major organization like the Metropolitan Opera or the San Francisco Symphony, or it can be a smaller organization, maybe one in your community. To get the most from this exercise, pick an organization that performs the kind of work you want to do or that’s the size of what you hope to create. Examine at least two years of the organization’s financial statements and see how much money is coming in, from where, and how it is spent. What are the organization’s assets? What are its biggest expenses? Be sure to read any footnotes in the financial statements, as that is often where some of the most crucial and fascinating information is located. As we’ve said, it can be powerful to investigate an organization you’re hoping to work for. Examining its financials can give you a sense of the organization’s long-term prospects and what the salary ranges of its top officers are, or at the very least give you some insightful questions to ask during an interview.

- •Try your hand at creating a business plan! First, brainstorm potential ideas, without worrying too much about how crazy or unworkable they might sound. Then, take the one that excites you most and submit it to the planning process we talk about in this chapter. Dream big, but don’t underestimate how much time, effort, and cash you’ll need to get started.

- •Have an entrepreneurial workshop. Gather some friends and colleagues and put your heads together to discuss existing ideas and brainstorm new ones for performing arts projects. The group doesn’t have to be made up of just performing artists. In fact, the more diverse the gathering, the richer and more creative the discussion is likely to be. Take some time to prepare a presentation about your idea. Give everybody a chance to give their feedback or to riff on your project and come up with productive variations. Make an effort to create an atmosphere where the focus is on brainstorming and constructive criticism. Don’t worry about your idea being perfect, and don’t let the discussion get too critical. Especially in the beginning, new and potentially successful projects are going to be rough, imperfect, and not entirely thought out. This is entirely natural. Bring the same tolerance for the creative process to your entrepreneurial workshop that you would to a collaborative work of theater, dance, or music that is still in process.