Chapter 3

Project Phases

How do the firms and individuals planning and building a theater organize their work? A comparison to a stage production is again helpful—from script selection to opening night, a stage production follows a conventional process understood by just about everyone involved:

- Pre-production—budgets and concepts

- Production—rehearsal and build period

- Transfer to the theater—load-in, technical, and dress rehearsals Performances

At its most basic, a building project is also a four step process:

- Pre-design

- Design

- Construction

- Occupancy

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) has adopted a widely followed set of project phases. In the AIA phases, “design” is further divided into schematic design, design development, and contract documents. The AIA also divides “construction” into bidding and construction administration. And on a performing arts building, construction administration is usually followed by a period of final testing and tuning, so the complete conventional list of phases is:

- Pre-design

- Design

- Schematic design

- Design development

- Contract documents

- Construction

- Bidding

- Construction administration

- Final testing and tuning

- Occupancy

On any given project the process may be streamlined or more complicated. But some variation of this process is used everywhere in the world.

Design Phases

Each project phase is dependent on the work of the previous phase—it builds on that work, and also places limits on the work of the succeeding phases. The design phases are especially interdependent in this way, and this interdependence bears discussion before we describe each phase.

Design Is Iterative

The design of theater buildings is iterative. This is true at the macro level— during each of the design phases the project elements are examined and documented. Then in the next phase, these elements are further refined and developed, and documented again. At each phase the design is more detailed and more of the design disciplines become involved.

Design is also iterative at the micro level. Any given building element may be revisited again and again—refined, improved, adjusted to accommodate related and adjacent elements, and finally, detailed and specified for construction.

Every Design Is Unique

At each step in the micro and macro processes, the owner and design team make decisions. The completed design is an accumulation of thousands (perhaps tens of thousands) of discrete decisions, and the result is a unique

response to the owner’s needs. The building committee chair for a new arts center, who was also the head of a large manufacturing company, told the architect he didn’t want his new arts center to be “serial number one.” The architect replied that his firm had designed many arts centers and that this new building would be a “production model” not a prototype. This was an appropriate and reassuring response to the client’s underlying anxiety. But it was disingenuous, since every new arts building by definition is “serial number one.”

Design Is Risky

It follows that risk is inherent in the design and construction of theater buildings. In making those thousands of decisions, the owner and design team will get some wrong. Some of those wrong decisions may come to light during a later design phase, or during construction, and the design will be adjusted. Of course the builders must make hundreds or thousands of decisions as well, and some of those will be wrong, too. Inevitably, some problems will not be obvious until the building is completed and then it may be too late for corrections.

Almost every new building has a few disappointments. On most projects such problems do not seriously diminish the building’s aesthetics or function. And it’s important not to let the new building be defined by the outcome of a few wrong decisions, rather than the thousands of right ones. Of course, on a very few buildings serious issues arise after occupancy, and expensive fixes must be undertaken.

The design team’s responsibility in all this is to perform services to an appropriate standard of care. This is usually described as performance “consistent with the professional skill and care ordinarily provided by professionals performing similar services on similar projects.” The design team (or its insurance companies) must provide redress for problems resulting from substandard performance. However, so long as the design team performs to the appropriate standard of care, it is not responsible for the vagaries of the design and construction process.

Some owners try to shift the risk of the design process to the design team by defining a higher standard of care, or even attempting to require that the design team guarantee the outcome of the design and construction process. However, this is beyond the ability of even the most talented and foresighted design team, since much of the process is outside of their control.

Choices Become More Limited Over Time

The iterative nature of design also places greater constraints on the owner and design team at each step in the process. As the decisions accumulate, the options for changing the design become fewer. This means the early phases of the project are the most critical—the decisions made during pre-design and schematic design will largely determine the ultimate success of the project. Not coincidentally, it’s during these early phases that the owner and users have the most influence over the project. The decision-making in the later phases is more technical and is largely left to the design team and builders.

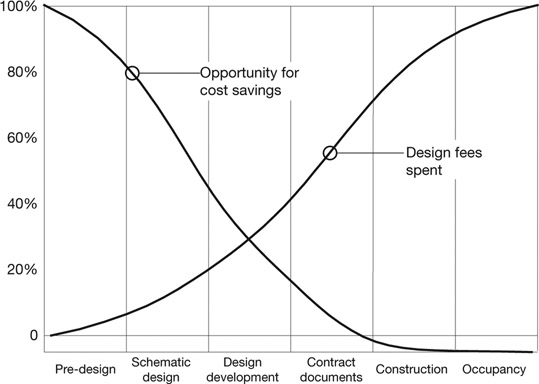

Cost Savings Are Less Over Time

It’s also at the outset that the owner has the best opportunity to control project costs. About 20 percent of design fees are spent during the pre-design and schematic design phases, but it’s during these two phases that the decisions affecting 80 percent of the cost are made. The opportunity to reduce cost diminishes as the design decisions become more limited in scope.

To illustrate, here’s a hypothetical example about a dance rehearsal room.

Pre-Design and Schematic Design

Should a dance rehearsal room be included in our new building? Questions about including (or excluding) significant building elements are appropriate for pre-design and still possible in the schematic design phase. The owner’s decision on the rehearsal room will change the construction cost by $500,000 or more. Let’s say the owner decides to increase the budget and the dance rehearsal room is integrated into the schematic design. The dance instructor is quite happy.

Design Development

The rehearsal room’s finishes and services are defined in the design development phase. A maple basket weave floor is detailed, and an appropriate audiovisual system is specified. Dance barres, large mirrors, and curtains to cover the mirrors are shown on the drawings. The structural, HVAC, and electrical systems are defined.

At the end of design development the project cost estimate comes in high. The owner might be regretting the decision to add the dance rehearsal room, but the room is well integrated into the overall design and removing it now is not very feasible. The design team would have to redo significant work, which would delay the project and may require additional fees.

How else can costs be reduced? The total cost of the barres, mirrors, curtains, and audiovisual system might be $100,000. These items could be removed from the construction contract and furnished by the owner. This does not actually reduce the cost but shifts it to another budget or defers it to a later date. How about the basket weave floor? It’s desirable for dance, but it’s expensive and requires an extra deep slab depression. A simpler floor construction would cost less and may reduce the cost of structure as well. The dance instructor consults with colleagues and agrees the simpler floor is acceptable. The less costly floor saves $50,000, so the floor is changed.

Contract Documents

In the contract documents phase, the structural engineer designs and details the building structure to accommodate the less expensive floor. The architect specifies and details the floor and the edge conditions where the maple surface meets surrounding floor finishes. If more savings are needed, our choices now are quite limited. We could switch the top layer of the floor from 25/32″ T&G (tongue & groove) maple to 3/4″ Plyron sheets. This requires just a few changes to the floor details and specification, and doesn’t affect other parts of the design. This change saves $5,000.

Bidding and Construction

Once the bids for construction are received, it’s no longer a question of reducing costs but of avoiding additional costs in the form of change orders. Suppose a donor emerges during construction who wishes to pay the cost of adding back the maple surface. This requires changes to agreements with the contractors and suppliers. The Plyron is probably on order; it may even be on the jobsite. The cost to change the top surface from Plyron to maple will likely be $10,000 to $15,000—much more than the $5,000 we saved in the change from maple to Plyron.

Of course, the owner can cancel or significantly revise the project at any point in design, but the cost of doing so increases as the project progresses. Major changes made late in the design process can be very expensive and can delay the project. For this reason it’s critical to spend adequate time on the early project phases. And to protect everyone, the results of each phase should be well documented and signed off by the owner before the next phase is begun.

With this background, let’s move on to a description of each of the conventional phases.

Pre-Design

Pre-design may also be called pre-schematic, programming, project feasibility, or various other names. The basic questions that pre-design answers are:

- What are the needs to be addressed?

- Is a new or renovated building the right response to those needs?

- What should be built or renovated? What kinds and numbers of rooms should the building have? In other words, what is the building program?

- How much will the project cost and how much is the owner able and willing to spend? That is, what is the project budget?

Pre-design may be performed by the owner without the involvement of any consultants, but most owners do not have the necessary resources and expertise. More often a consultant or a team of consultants is engaged—this team may be led by an architect, theater planner, arts management consultant, or by a consultant who specializes in architectural programming services. Once pre-design is complete, the same team may be retained for complete design services, or the owner may advertise for a new design team. On some publicly funded projects, the pre-design team is prohibited from performing the subsequent design work.

The result of pre-design should be a building program (a complete description of the building in words and numbers) reconciled to a project budget (more numbers). Owners and architects sometimes have the urge to jump right into design, but pre-design is a critical first step that should not be shortchanged. It will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 5.

Schematic Design

A primary task of schematic design is to organize the building, both functionally and aesthetically. The functional goal is to establish the sizes, shapes, and locations of each interior room, and to work out the best adjacencies and circulation paths between rooms. As noted in the first chapter, a theater has many individual rooms with unique requirements, making this a challenging task. The aesthetic goal is to make sense of the building massing—that is, the shape and appearance of the building as a sculptural object—and to fit the design into the context of the surrounding buildings or landscape.

There are projects in which the exterior form of the building was decided first, and the interior program elements were accommodated as best as possible within this form. The Sydney Opera House is a famous example of “designing from the outside in.” At the other extreme, the appearance of some theater buildings suggests a functional plan was established, and exterior walls and roofs were added, with no thought to the aesthetics of the building form. This is “designing from the inside out.” Neither approach is satisfactory. The functional and aesthetic goals are interdependent and must be addressed together.

This process is iterative, and will heavily involve the design architect, theater planner, and acoustician. The theater planner and acoustician will be more focused on function, and the design architect on aesthetics, but not exclusively so. These core design team members also work together to establish the basic geometry of the performance spaces. The structural engineer will advise on possible approaches to the building structure, and a preliminary structural grid will be established. The MEP engineers (mechanical, electrical, and plumbing) will document the design loads for these systems, and focus on reserving adequate space for equipment rooms and duct and riser chases. The IT consultant will reserve an excessive amount of space for telecom and data rooms. In this phase, the executive architect is man aging the design team’s effort, arranging and minuting project meetings, and advising on local regulatory and construction issues. The owner and users participate in many of the meetings during this phase, though the design team may also schedule work sessions without the owner.

The schematic design package will include drawings—plans, elevations, and sections—and narratives describing materials, finishes, acoustic requirements, theater equipment and accommodation, the structural system, and MEP systems. Unless the project is quite small or the schedule is unusually fast, the design team will issue progress sets. These are labeled with a percentage indicating how complete the work of the phase is—50, 90, and 100 percent are typical. The cost model will be updated based on the 100 percent complete package, and the owner will be asked to approve both the package and the estimated cost before the next phase commences.

Design Development

The task of design development is to refine and develop the design, again both functionally and aesthetically. Ideally, a design development package reflects a completely thought out design intention. The interior architecture of the performance spaces is defined—for example, shaping and detailing of walls, ceilings, and balcony fronts. Room layouts, furniture, and equipment are shown on the drawings. The structural, mechanical, and electrical systems are fully developed and integrated with the architectural design. Materials are selected, and critical finishes are shown on the drawings.

The role of the executive architect increases significantly in design development. It’s common for both the design and executive architects to have drawings in the design development package. While the design architect continues to develop and document the interior of the building, the executive architect is probably taking ownership of the building plans, confirming the structural grid, and preparing background drawings for the engineers and consultants to use. The executive architect may begin to detail the exterior elevations, wall sections, elevators, stairs, and similar building elements.

The design development package will include hundreds of drawings prepared by the architects, engineers, theater planner, acoustician, food service

Table 3.1 CSI MasterFormat Divisions

| PROCUREMENT AND CONTRACTING REQUIREMENTS | |

|

|

|

| 00 | Procurement and Contracting Requirements |

|

|

|

| SPECIFICATIONS | |

|

|

|

| General Requirements | |

| 01 | General Requirements |

|

|

|

| Facility Construction | |

| 02 | Existing Conditions |

| 03 | Concrete |

| 04 | Masonry |

| 05 | Metals |

| 06 | Wood, Plastics, and Composites |

| 07 | Thermal and Moisture Protection |

| 08 | Openings |

| 09 | Finishes |

| 10 | Specialties |

| 11 | Equipment |

| 12 | Furnishings |

| 13 | Special Construction |

| 14 | Conveying Equipment |

|

|

|

| Facility Services | |

| 21 | Fire Suppression |

| 22 | Plumbing |

| 23 | Heating, Ventilating, and Air Conditioning |

| 24 | Reserved |

| 25 | Integrated Automation |

| 26 | Electrical |

| 27 | Communications |

| 28 | Electronic Safety and Security |

|

|

|

| Site and Infrastructure | |

| 31 | Earthwork |

| 32 | Exterior Improvements |

| 33 | Utilities |

| 34 | Transportation |

| 35 | Waterways and Marine Construction |

|

|

|

| Process Equipment | |

| 40 | Process Integration |

| 41 | Material Processing and Handling Equipment |

| 42 | Process Heating, Cooling, and Drying Equipment |

| 43 | Process Gas and Liquid Handling, Purification, and Storage Equipment |

| 44 | Pollution Control Equipment |

| 45 | Industry-Specific Manufacturing Equipment |

| 46 | Water and Wastewater Equipment |

| 47 | Reserved |

| 48 | Electrical Power Generation |

consultant, architectural lighting designer, and other design team members. Some of these drawings will be developed into contract documents in the next phase. Other drawings will not. For example, the theater planner will prepare general arrangement drawings showing special structural and electrical needs, and the acoustician may prepare building plans showing acoustic requirements for walls and doors. The requirements shown on these drawings will be incorporated into the contract documents prepared by other members of the design team.

The design development package will also include preliminary specifications, often in outline form. Almost all projects in North America and many projects elsewhere use the specification format published by the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI). The CSI MasterFormat organizes the work into standard divisions, and individual systems or products are organized into sections within each division. For example, Division 05 is “Metals” and Section 05 12 00 is “Structural Steel Framing.” As a general rule, the scope of a project is shown on the drawings, while qualitative and procedural requirements are included in the specifications.

Progress sets are typically issued when the design development phase is 50, 75, 90, and 100 percent complete. The cost model may be updated midway through design development and again at the completion of the phase.

Contract Documents

The drawings and specifications prepared in this phase become part of the contract between the owner and builder—hence “contract documents.” This phase is also called working drawings or construction drawings, since the builders use these drawings to guide the work of construction. If the design development package defines a completely thought out design intention, then the task during construction documents is to coordinate and document that design for bidding and building.

At this point the executive architect is responsible for the documents, although the design architect will continue to make significant contributions. The design architect may be responsible for certain specification sections or may even prepare some of the drawings. Each of the engineering disciplines and the theater planner will prepare specifications and a significant number of drawings. The design team members who do not issue their own drawings at this phase—acoustician, architectural lighting designer, food service consultant, graphics designer, etc.—will carefully review the drawings prepared by the other design disciplines to confirm that their work and advice have been incorporated.

By way of example, at the time construction of the Overture Center in Madison, Wisconsin began, the contract documents included five bound volumes of architectural drawings and one volume each for structural, theater equipment, piping (plumbing and fire protection), mechanical (HVAC), and electrical—more than 1,000 unique drawings in all. See Table 3.2 for a description of each volume. Including revisions, the design team formally issued more than 5,000 drawings between the start of schematic design and the beginning of construction. Detailing and coordinating the work of all these design disciplines across so many sheets of drawings is a challenge, and this occupies most of the design team’s time during the contract document phase. Progress sets might be issued at 35, 65, 95, and 100 percent complete.

The extent of coordination required is often a surprise to members of the design team who are not familiar with theater buildings. If the architect has previously been suspicious of the theater planner’s statements about the project’s complexity, it’s at this point that he or she may reconsider. If the team began the contract document phase with some design issues unresolved—a common event—then the task of coordinating and detailing is made that much more difficult. And unfortunately, it’s at this critical time that the design team may be running out of time, fee, and oomph. If the 100 percent set is not completely coordinated there will be pressure to put the project out to bid anyway. The project schedule may have been stretched to its limit—construction must start before the authorizing legislation expires, before the winter sets in, or before the lead donor gets very much older! The design team has billed out 75 to 80 percent of its fees and continuing coordination efforts will eat into the profits—if there are profits. Design firms’ responses to this situation vary greatly. Some firms will reassign almost all of their project staff (presumably to money-making projects) leaving one or two poor souls to continue the coordination and detailing work. Other firms will send in a fresh and experienced “relief team” for a concerted push to finish up the documents.

Bidding

When the contract documents are complete, the project is bid or priced. (In British English this process is called tendering.) Documents that define the bidding requirements (informally called the front end) are added to the

Table 3.2 Contract Document Drawing Volumes: Overture Center, Madison, Wisconsin

|

|

| 1 STRUCTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2A ARCHITECTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2B ARCHITECTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2C ARCHITECTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2D ARCHITECTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2E ARCHITECTURAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 NOT USED |

|

|

| 4 NOT USED |

|

|

| 5 THEATRE EQUIPMENT |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 PIPING |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 MECHANICAL |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 ELECTRICAL |

|

|

|

contract documents, and the resulting package is known as the bidding documents. Builders interested in providing the work analyze the bidding documents and estimate the materials, labor, and equipment needed for construction. From their analysis, they develop and submit a price. The specifics of bidding will vary depending on the project delivery method (also called project procurement or contracting method). Procurement methods and the builder’s role in bidding and construction are discussed in Chapter 4. The design team’s role is discussed below.

The owner and design team may hold a pre-bid meeting for potential bidders. The purpose is to answer questions about the bid process and the documents, and to allow the bidders to familiarize themselves with the site conditions.

Bidders may submit questions about the documents—these are called requests for information or RFIs. Some bidding documents may require bidders to propose product substitutions for approval prior to the deadline for bid submission. The design team’s response to RFIs and substitution requests will be in the form of an addendum to the bidding documents distributed to all of the bidders. The addendum may include written responses to questions, revisions to specifications, sketches, and new or revised drawings.

Once bids are received, the design team participates in analysis of the bid results, evaluation of substitutes, and confirmation of scope. Sometimes individual pre-award conferences are held with the top two or three bidders to confirm that their bids are responsive—that is, that they conform to the substantive requirements of the bidding documents. Often on publicly funded projects, the construction contract must be awarded to the bidder who submits the lowest responsive bid. The construction contract usually stipulates both the price (called the contract sum) and the number of days before the building is expected to be ready for occupancy (contract time).

Construction Administration

The builder generally has control of the construction site and authority over the “means and materials” of construction. The construction contract requires the builder to conform to the “design intent” as described in the contract documents. The architect’s contract with the owner gives the design team the authority to interpret the contract documents for both the builder and the owner. The architect may also have the responsibility of monitoring the completeness of the work and approving the builder’s pay applications. The design team’s role during construction is therefore called construction administration.

With so much at stake, project communications and documents are treated more formally once the construction contract is awarded. The AIA publishes standard forms and other materials that can be used to manage project communications during construction, but today much of the communication is handled through project management websites.

Requests for Information

The builder will ask questions about the contract documents by submitting a written request for information (RFI) which the design team will answer in writing with support material if necessary.

Submittals

The construction contract will require the builder to submit samples, mockups, product data, and fabrication and installation drawings for elements of the work. These submittals are reviewed by the design team for conformance with the design intent, marked up, and returned to the builder.

Field Reports and Punch Lists

Another way the design team monitors the builder’s conformance is by walking the construction site, reviewing the completed work, and documenting any concerns or observations in a field report. On large projects the architect and other design team members may have project representatives permanently on site to review the work in progress. As the building nears completion, the design team will prepare a punch list of the work remaining to be completed or needing correction.

Supplemental Instructions and Change Orders

The design team may make clarifications or minor changes to the work by issuing an architect’s supplemental instruction (ASI). For changes or additions that affect cost and schedule, the design team may issue a proposal request to the builder. If the owner accepts the builder’s proposal, the design team issues a change order—this modifies the contract documents and adjusts the contract sum or contract time or both. If a change affecting cost and schedule is needed, but there isn’t enough time to solicit a proposal and issue a change order, the designer can issue a construction change directive (CCD). This requires the builder to make the change, with adjustment of the contract sum and time to follow, which may lead to disputes about the value of the change.

Delays

Changes to the contract time are important because some contracts specify liquidated damages. These are damages that the builder must pay the owner if the building is not ready on time—say, $1,000 for every day that occupancy is delayed. These amounts are not meant to be a penalty, but are compensation to the owner for the loss of use of the building, due to the builder’s failure to perform on time.

The builder may also claim delay damages against the owner if, say, the information necessary for construction isn’t provided in a timely manner or the contract documents are so deficient that they contribute to delays in the work. The builder will seek compensation for the extra costs associated with the delay, and perhaps compensation for the construction work he or she could have been performing on other projects had the delays not occurred.

Does This Sound Adversarial?

It doesn’t have to be, but sometimes it is. The following anonymous example happened at a large university, but the situation can be found on projects of all sizes: the relationships between the owner, builder, and design team became very adversarial on a large performing arts center, resulting in many disputes and causing several people to leave the project and their jobs. One of the site architects observed that the builder’s project manager was putting more energy into assembling a delay claim than into the actual work. And, late in construction, the builder did file a very substantial delay claim against the owner. The builder and owner reached a settlement without consulting the design team, and two things happened immediately after: the builder recalled its project manager to corporate headquarters, and the owner sued the design team for indemnity—that is, to be reimbursed for the damages paid to the builder. The owner and design team eventually reached a settlement. Fortunately, the design team had jointly purchased a project-specific professional liability policy, and it was this policy that largely funded the settlement with the owner. The owner eventually took occupancy of the building, although the punch list was never completed. And the users—the only group left unscathed by the construction process—absolutely love their building. Fortunately, most construction projects are much more collegial, or at least much less adversarial, than this example!

Final Testing and Tuning

Final testing (or acceptance testing) of the theater equipment is performed by the theater planner. If the facility is to be used for music, the acoustician also tests and “tunes” the room with assistance from the theater planner. Final testing and tuning is sometimes called “commissioning.” But as commonly used in design and construction, commissioning concerns the building management system and building services—HVAC, electrical, fire alarm, etc.—and is usually performed by an independent commissioning authority or agent directly under contract to the owner. To avoid confusion, “testing and tuning” is the preferred term for what the theater planner and acoustician do.

Most performance equipment is completely custom—the British say “bespoke,” which makes one think of men’s suits. Or it is a highly customized assemblage of more or less standard pieces. In either case, we can’t really know if it all works together as planned until it’s complete and tested. The goals of final testing are to confirm that the installed equipment complies with the design intent and contract requirements, to put the equipment through its functional paces, and to coordinate final corrections and adjustments.

If an auditorium is intended for music, the acoustician will take measurements to determine how quiet the room is and how the room responds to various-sized musical ensembles. Often the acoustician takes advantage of the “hard hat” performance given for the construction workers to record the response of the room with an audience. The acoustician compares these measurements with the design criteria and proposes adjustments to the HVAC system, room finishes, etc. if required. If the room is equipped with adjustable acoustic devices—a demountable orchestra enclosure, forestage canopy, adjustable absorption, or reverberation chambers—the acoustician and theater planner work together to confirm their proper operation, determine placements and settings, and program the system controls.

Occupancy

Surprisingly, most design teams have little formal role as the owner and users take occupancy of the new building. Most construction contracts require the builder to provide training for the users in the operation and maintenance of the building systems, and the designers may monitor this training. The design team also reviews the O&M (operation and maintenance) manuals prepared by the builder, to ensure that they adequately document the building systems. And the design team may prepare record drawings for the owner’s use. These are revisions of the contract documents that incorporate the changes made during construction.

If the new building is opening with a public performance, the theater planner may attend the technical rehearsals to advise on the theater equipment systems and to help resolve any problems that may arise with the equipment. Similarly, the acoustician may attend music rehearsals. This level of involvement is almost never required by contract, however, and in some cases it may even be unwelcome.

While the owner and users are taking possession of their building, the designers and builders are marking the end of a project that has consumed several years of their professional lives. The hard hat performance mentioned above is often an opportunity to celebrate and say goodbyes. The opening performance is often a fundraising event for the owner, but the design team members will appreciate the opportunity to attend, whether tickets are complimentary or paid.

Post-Occupancy Walk-Through

Even after occupancy the design team will assist the owner in getting any deficient work corrected. Sometimes the design team’s contract includes a post-occupancy walk-through. This is usually scheduled about a year after opening, but prior to the expiration of the builder’s warranty so that the design team can assist with any warranty repairs.

Postmortem

Project teams often gather for a postmortem with the owner and users—meeting one or two years after opening to discuss the users’ experience and the building’s performance. Although rarely a contractual requirement, it’s a great opportunity to learn from the project and to maintain relationships with the users.