Chapter 6

Eight Steps to Keeping Your Show On-Brand

This chapter presents an eight-step framework that keeps your show aligned with your brand. Alignment ensures that your show will reinforce rather than confuse the identity of your brand. This helps your show to become part of your brand strategy and a tool for building brand equity.

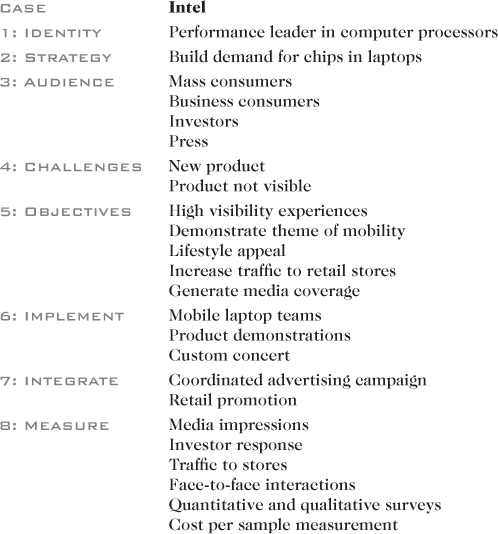

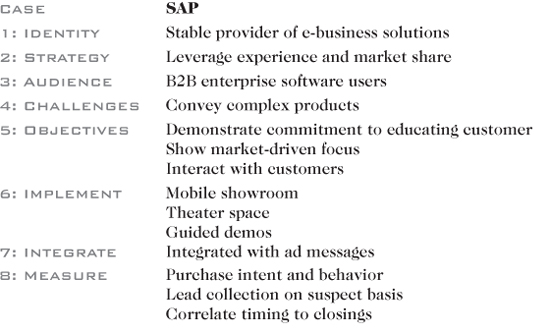

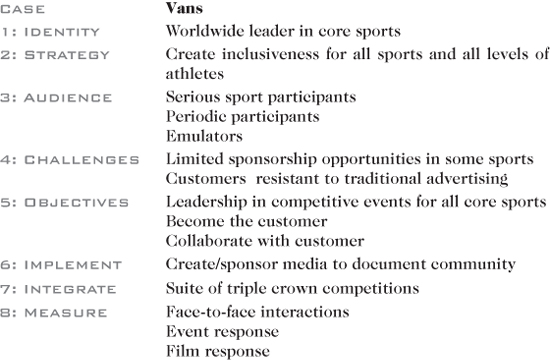

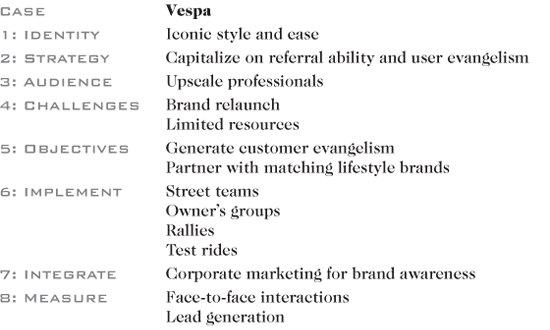

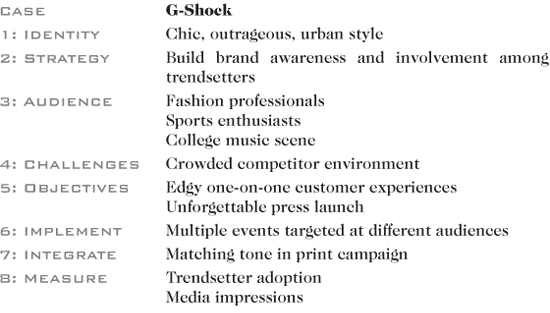

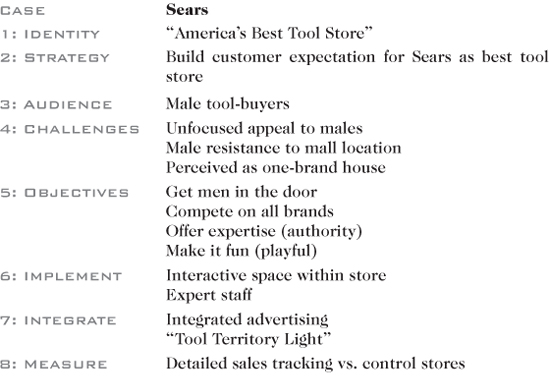

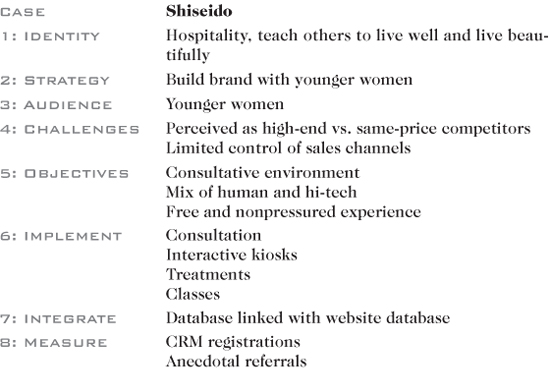

The eight steps of this framework can be seen below in the Eight-step framework for keeping a show on-brand. Moreover, each step is illustrated in Cases of the eight steps to keeping a show on-brand (on page 94) with 10 cases that we introduced previously.

Cases of the eight steps to keeping a show on-brand

Step 1: Know Your Brand Identity

The first step in creating a show is to understand the identity of your brand and to align the show with the brand identity. The identity of a brand includes its core image and personality. That is, what does the brand currently mean, both within your company and to the various external constituents who interact with it (mass consumers, business customers, investors, press)?

In each of the cases of successful show business that we have seen so far, the company began with an understanding of its own brand in planning what kind of show to put on. After all, any show should be an expression and reinforcement of the identity and meaning of your brand, in addition to any other marketing objectives it may fulfill.

In the case of SAP's E-Business Solutions Tour, the show was carefully designed to express its brand identity as a stable, highly experienced provider of e-business solutions in a post-dot-com economy. For Intel, the mobile messenger show and events for the Pentium 4 Processor-M chip were a new way to prove once again that their brand identity is about being the performance leader in computer processors. For the Vans athletic apparel company, its shows in movies (Dogtown and Z-Boys and others) and in hosting competitive events were designed to further its brand identity as the worldwide leader in core sports.

Step 2: Know Your Brand Strategy

As brand managers know, however, the identity of a brand is never constant. Brands are in a perpetual state of flux and change. Therefore, a brand strategy must always address the question of movement: where do we want this brand to go? This could include a broadening of consumer awareness, a deepening of customer involvement, more community building, or leveraging the brand into a new product category or in a new market. Any show therefore needs to be aligned with the overall strategy for its brand. When generating concepts for a creative show that will deliver value both to customers and to your business, understanding your overall brand strategy is the best way to start looking for ideas. Do you want to create an event to build a stronger brand community? Or an experience that will increase awareness or support a brand extension?

In the case of Crayola, a strategy had been formulated to tap into unused brand equity by moving the brand from a product-focused positioning to a brand that provided experiences and solutions for creativity to children and adults alike. It was this strategy that led directly to the concept of an experiential space devoted to customer creativity and interactions. For Vespa, relaunching its brand in the U.S. market after many years and with limited resources required it to capitalize on user evangelism and the product's referral ability—hence the various shows to promote word of mouth and group riding. Intel's strategy was to respond to research forecasting strong growth in the notebook segment by introducing a new processor chip for mobile computing and building demand for it among personal and business consumers. The Pentium laptop shows were designed to generate local excitement for the new chip's launch in tandem with traditional advertising.

Step 3: Know Your Target Audience

In order to turn a brand strategy into a show business plan, companies need to know the target audience. Much more than traditional advertising, show business tends to focus on specific customer groups and therefore needs to know who are the most valuable or crucial customers.

For SAP, the audience consisted of key decision-makers in the purchasing of enterprise software solutions, an educated audience who would demand sophisticated information as well as compelling experiences from their show. Vans identified three tiers of users to appeal to in each of the core sports: serious athletic competitors, periodic participants (e.g., seasonal snowboarders), and lifestyle emulators. Then Vans built its shows to provide close interaction and identification with all three groups, and also to avoid any hard-selling that would weaken a sense of community between the brand and the customers. For Sears's Tool Territory show, the targeted customer was the male tool buyer who should have been viewing Sears as his best store.

We will return to the subject of knowing, learning from, and building relationships with your customer in greater depth in Chapter 7, Creating Relationships Through Show Business.

Step 4: Know Your Strategic Challenges

Next, it is important to identify the key challenges or obstacles to achieving your strategy with that particular audience. Knowing these challenges will help you to focus the objectives of your show and increase your chances of success by helping you address your greatest risks.

For Vans, the challenges included a customer group that was extremely resistant to traditional advertising. Thus, the show had to support their enthusiasms and provide the right activities rather than hard-selling the brand and its products. Crayola's biggest challenge was insufficient brand affiliation by adults and a limited understanding of its customer's needs.

For Sears's Tool Territory, the key challenges included not only male customers' dislike of its mall location, but the perception that the store carried only its own brand of tools. This last challenge was a particularly onerous one if Sears was going to truly embody its brand promise to be "America's best tool store," and required the company to drastically rethink its approach to merchandising and pricing of tool brands.

Step 5: Identify Show Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The next step is perhaps the most critical step. Here we develop specific objectives and expected outcomes out of what we have learned thus far. The objectives for the show will identify the kind of experiential impact that the show should have: what will the show demonstrate about products? What will it communicate about the brand? What kind of customer interaction will it provide? What kind of value will it provide? What should people remember or talk about after they see the show?

These are specific tactical objectives for the show itself, but they need to develop out of the prior four steps of this framework. A show's objectives must develop: from your brand, toward your strategy, for your audience, and in response to your challenges. The objectives also help define the spirit of the show. This is where you identify what the experience should feel like; in other words, how the show will be entertaining, engaging, and boundary-breaking.

Objectives should also be linked to expected outcomes, which can be used to measure the show's success. What will this show hope to achieve? What will it change?

For Intel's show, the objectives included demonstrating the theme of mobility in a funny and interactive way by linking laptops to a lifestyle appeal of both mobile computing and popular music and culture. Expected outcomes based on these objectives included media coverage and increased traffic to key retail stores for the launch.

SAP's objectives for its Tour were to demonstrate a commitment to educating its customers by creating a theatrical and thrilling show that demonstrated the market-driven focus of the company. Expected outcomes were increased sales from new customers. For Crayola, key objectives included creating an environment for brand immersion and affiliation through creativity, and linking the brand to school arts initiatives during a time of school budget cuts. Expected outcomes were new models for future retail space development and new customer insight for product development.

Step 6: Implement, i.e., Put on the Show

The sixth step of the framework is implementation: to put on the show. The implementation of the show will be based on the objectives you have set for it (and thus, it will be aligned with your brand, strategy, audience, and challenges). The heart of implementation is the creativity of the people who are designing and enacting the show.

As this creativity runs its course, you will want to ensure that your brand is integrated throughout the implementation of your show.

This may seem like an obvious rule, but surprisingly it is one that is inconsistently carried out when many companies attempt to reach customers by something other than traditional advertising. Integrating your brand's meaning into an event does not mean hanging a giant logo over your stage or trade show booth, or making sure that your new retail store uses the colors of your brand's visual identity. It means injecting the spirit and character and design elements of your products and services seamlessly into the creative execution of your show at every level.

This is not just creativity with a banner up top. Think of the press party for Casio's G-shock brand. The design of its watches was what they were trying to link to an edgy brand identity; so the watch design was incorporated every step of the way: from the black-leather-clad invitation (the text was laid out in the shape of a wristwatch), to the S&M floorshows at the party (where the performers' costumes wove together watches with chains, leather, and latex), to the product demonstrations where G-Shock watches were subjected to crushing and grinding by black stiletto heels.

Another example of thoroughly integrating the brand into a show is the concert by the Barenaked Ladies which capped the day-long show to launch Intel's new laptop chips. Usually, when a known rock band appears under the sponsorship of a company, the brand is limited to banner appearances and more signage outside the venue. In this case, because the concert was a custom event, Intel had much more control. The concert stage was designed by Intel to incorporate the mobile computing theme: instead of the standard big screens on either side of the stage for the more distant audience to watch, Intel built giant mock laptops to display the footage of the band. The band itself got involved too, to a degree unheard of in a standard sponsorship relationship. Having been given information on Intel's product and the customer lifestyle it was supposed to be a part of, the Barenaked Ladies decided to create an original song for the event that included references to the marketing messages for the launch and to customers' use of the product (for digital video, audio, games, etc.). Toward the end of concert, when the 70 mobile messengers arrived as a group at the edge of the audience, the band greeted them with banter and jokes about their costumes as well.

All of which makes us wonder about the non-show-business model of music or sports sponsorship, where sponsors like Visa pay high fees for very restricted associations with an event. How much is the sponsor really gaining from its association with the performers? If companies saw artists and celebrities less as marketing tools to be bought (like time slots on television) and more as partners with whom to find creative ways to collaborate, a show business model of sponsorships could provide more value for companies and for customers.

Figure 6-1. The Barenaked Ladies not only rocked the house at Intel's launch party, they wrote their own song about the brand. Photo courtesy of Intel Corporation.

Step 7: Integrate with other Marketing

The seventh step of the framework is to integrate your show with all other marketing communications used to promote your brand. Show business does not happen in isolation, and in most cases companies putting on shows are still relying on traditional marketing communications tools as well. Therefore, one important part of managing the brand impact of any show is to assess what your company's overall communication mix is and find ways to enlist or utilize those other resources. If your company makes a lot of use of broadcast advertising, then try to arrange for some of it to promote or draw attention to your show. Or at least, look for ways to link your show's themes to the brand messages in current media campaigns.

Because show business tends to happen on a very local level, its relationship with other marketing tools is often "local vs. global." In these cases, advertising and other tools are often used to create broad brand and product awareness across demographics, whereas show business can be used to approach more targeted customer groups, and to give them a much deeper experience of the brand, products, or services. Coordination needn't be very rigorous between the two for them to complement each other. In the case of Vespa, Piaggio USA's initiatives have focused on this kind of broad brand promotion, while the local dealers have initiated the street teams, events, and riders groups that have brought the brand to customers close-up.

Other examples of marketing integration for shows we've seen include:

- Intel's national advertising campaign to launch the Pentium 4 Processor-M chip, with the same theme as the launch events: "desktop performance without the desk"

- SAP's careful coordination of the E-Business Solutions Tour's messages with their advertising messages and their theme that, "The best run e-businesses run SAP"

- Sears's use of billboards and TV commercials that stressed the identity (playful + authoritative) of Tool Territory, with themes like, "Daycare at the mall for men," and "18,000 tools in stock. Collect them all"

- Casio's print advertising for the G-shock brand, which carried the same edgy personality, though with different themes for various target audiences

The example of G-Shock raises an important point, which is that integration should focus on coordinating the meaning of a brand and the spirit of its expressions. Integration of exact slogans, wording, fonts, and visual identity can be necessary at a certain level for large organizations and brands, but should be handled with care so as not to squelch the vitality of local brand expressions, especially in show business.

"We've seen that the Integration Emperor has no clothes," says Drew Neisser, who designed both advertising and show business events for G-Shock. "If you try to integrate a brand visually and verbally across all audiences and across all media, you will end up compromising all the media, to their lowest common denominator."

Step 8: Measure Brand Impact and Alignment

The final step of keeping a show on-brand is to measure and evaluate its results after implementation. We suggest that you measure both the alignment of the show with the brand and audience (Did the experience match the identity and strategy for the brand and its target audience?) and its impact on the brand (in terms of audience awareness, perception, and bonding with the brand). We have listed measurement as a step after implementation, but in fact, for any measurement of impact, there will need to be a benchmarking measurement done before the show occurs.

Brand measurement needn't be expensive. For some goals, it can be achieved by adding a qualitative or attitudinal component to an exit survey or even by informal gathering of customer feedback through face-to-face interactions at an event. In most of the cases we have seen, brand impact and alignment is measured in only the most informal and anecdotal of ways. We would advise that such informal measurements could benefit from a regular process of recording and tabulating customer impressions that relate to the brand. At the least, brand alignment ought to be measured internally. Part of any project assessment should include ratings by managers who were involved in the show or observed it, regarding brand alignment and impact.

We will return to the topic of measurement and its relationship to budgeting and ROI for shows in Chapter 9.

Be Prepared to Evolve (Your Brand, Strategy, and Show)

As we discussed earlier, brands and brand strategies change. As a result, shows must be able to change as well.

If you are putting on a single-event live show, or other show with a short lifespan, brand evolution is not a real consideration. But if you are building an immersionary brand space or an expensive property for a traveling road show, and your space or property may be used for two or more years in order to maximize the return on the investment, you need to plan for changes in strategy.

Longer-term shows need to be designed at each step with flexibility to change in the future. Design components should be modular, content should be easily updated, and multiyear budgets should plan for significant overhauls rather than just maintenance repairs.

The SAP Tour has been used for shifting marketing goals each year that it has been in operation, with new deployments and sponsorships by differing SAP companies. What started as mostly a show to bring home a global branding campaign has evolved into a more sales- and lead-generation-focused marketing tool. This shift has come about mostly because of changing strategies on the best use of the property, but also because the success of SAP's global branding campaign in the first year meant that the Tour resource could be freed up for other marketing goals.

In other cases, a show will need to shift in order to remain in alignment with marketing communications (the challenge facing The World of Coca-Cola), or to remain in alignment with a brand whose identity or overall strategy is changing. Lastly, a long-running show needs to be capable of changing in response to the feedback it generates from customers. Since the experience is supposed to be for the customer, responsiveness to what they say about it is critical. As we have seen, one of the most important aspects of show business is its ability to help companies learn from their customers.

On-Brand or On-Customer?

This brings us to another challenge. The focus of this chapter has been on how to keep a show on-brand, which is extremely valuable. However, companies shouldn't just look inward toward their brands, but also outward toward customers. They need to align show business with both the brand and the customer.

To do that, companies need to move beyond the basic identification of customer segments and needs that we described in step three of this framework. A great show offers the possibility to progress from this initial kind of customer understanding to dynamic interaction and dialogue with the customer. This is the way toward building true relationships with customers that will deliver lasting value to a company. We show how to do this in the next chapter.