CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER THREE

Building a New Innovation Ecosystem

The Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation

Inspired by the past. Innovating for the future.

As we move forward into the 21st century, the need for transformative innovation in health care has never been greater. As Chapter 2 described, the cost and complexity of the current system have approached a tipping point, and the necessary transformations in the complex landscape of providers and payers are disruptive even to the most established players like Mayo Clinic.

As an organization, we saw this coming years ago.

Why? In part, for most of its history, innovation in health care has been largely centered on the development of clinical solutions—better treatments and more advanced technologies, instruments, equipment, and procedures. The vast majority of this innovation today occurs through publicly and privately funded efforts in universities and university hospitals. As noted in Chapter 1, we’re also quite involved in this innovation space; research is one of the three Mayo shields of practice, education, and research.

But most of this research is about pure medicine. It’s about treatments, healing, reversing disease, and dealing with symptoms rather than the patient experience and the processes supporting it. Most of the research targets “sickness,” not “wellness,” leaving a big part of our health experience unaddressed. Are we critical of such innovation? Hardly. It’s vital to the progress and quality of health care delivered in a clinical setting. We’ve seen some amazing things happen over the years.

Indeed, in the 150-year-old Mayo Clinic story of serving humanity and advancing medical science, we have had many impressive accomplishments including developing methods of freezing tissue to diagnose cancer during surgery; designing and using the first integrated patient medical record; developing an index with which to grade tumors; developing the first hospital-based blood bank; discovering cortisone, for which we were awarded the Nobel Prize; making the first FDA-approved hip joint replacement; installing and using the first CT scanner in North America; and developing a method for the rapid diagnosis of anthrax poisoning, which was needed in the aftermath of the September 11 and subsequent terrorist attacks.

But as the new millennium unfolded, we increasingly recognized a growing gap: no other research organization was focused on the design or effectiveness of the patient care experience. As we saw in Chapter 2, Mayo Clinic has understood the importance of the patient experience from the early days of Dr. Plummer and the integrated practice, so this research was a natural fit for us. We were indeed inspired by the past, and we saw a tremendous opportunity left on the table. We felt that if we created a dedicated focus to lead the way in the transformation to a 21st century model of care, we could also guide the continued success of Mayo Clinic. That focal point would dedicate itself exclusively to the experience and delivery of health and health care, and it would apply scientific and design principles normally reserved for clinical research to that experience. It would have to garner resources and organizational buy-in to succeed. As such, it would have to be formally established and embedded in the organization. It would have to apply a structured and well-understood methodology. It would have to do this all in a credible way, with credible leaders and support from high-level Mayo leadership to flourish.

Today, this organizational focal point exists and prospers as the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation (CFI). In this chapter, we will take you through the history and the guiding principles of CFI—how it evolved, how it overcame its challenges, how it approaches innovation, how it sits in the larger ecosystem of Mayo Clinic, and how it is likely relevant to your organization.

Meeting the Challenges

In 2001, coauthor, CFI cofounder, and formerly chair of the Department of Medicine Dr. Nicholas LaRusso pondered the establishment of an innovative franchise within Mayo Clinic to target the patient experience. At the time, he and his colleagues knew they had a lot of hurdles to clear.

There were the usual ones—hurdles like securing management buy-in, funding, and staffing and deciding how much to invest and ensuring a return on that investment. No matter what industry or what enterprise we sit in, don’t we all have these challenges when organizing a transformative innovation effort? Mayo Clinic was and is no different. It’s a big, complex organization with budget constraints and pressing deadlines and a talented staff dedicated to delivering what they are good at, day in and day out.

But in addition to those challenges, we had others to overcome. One, which may or may not apply to your organization, was the ongoing tension between the ethos and mindset of a physician and medical organization and the transformative innovation that we really had to achieve. For physicians, there’s a natural tension between medical exactitude—failure can mean death—and the back-of-mind knowledge that we should—and must—innovate. Further, especially as Mayo physicians, we have our traditions and a built-in conservatism to err on the side of patient health, safety, and well-being and to stay within ourselves, with what we know and can do. But mustn’t we also uphold the tradition of Mayo Clinic as clinical and medical practice innovators?

So how do we conceive and evolve an innovation organization in such an environment? How do we gain traction, and how do we do it quickly? We’ll admit—our evolution wasn’t so rapid. It has taken us about 11 years to get where we are now. We’d expect that to disappoint most of you trying to deliver aggressive and transformative change in your organization. We thought big and we started small, and we moved fast in specific areas, but health care is huge so we didn’t move very fast in the beginning. Probably not as fast as you want to in your organization.

And that’s why we want to share this recipe with you. We built the Center for Innovation very carefully with a sequence of iterative steps. We declared our focus and our vision. We got support from high-level leadership. We got an adequate, multiyear commitment of resources. We recognized early on that environments matter, and we created a visible physical presence conducive to innovation. We deployed credible leadership. We created a process focused on results, not on process, bureaucracy, and committees—specifically to avoid the 15 barriers to innovation called out in the previous chapter.

Not all of these steps worked perfectly. But if you follow our recipe, you should get there faster than we did. We proceeded visibly and inclusively, with stakeholders who understood and live these conflicts. We started with, but quickly moved forward from, a “skunk works” model, where innovations fly under the radar until they’re good enough to fly into the radar—because “conflicted” participants and especially management teams tend to fear under-the-radar programs. We chose to get and stay “front and center” with the organization.

We paid careful attention to the methods we used and to communicating our progress and successes (and our failures) to the rest of the organization. We viewed our role as not only to develop and implement innovations centered on the patient experience and health care delivery but also to inoculate the organization with innovation thinking—the competence and confidence to innovate on its own.

If you learn from our story and our success, we know that you can create a successful, embedded, credible, experience-driven innovation center within your organization. We feel that what we’re about to share will help you match our success but will take only a fraction of the time. That sounds good, but the bad news is that you will have to match some of the commitments made at Mayo—and that might not be so easy.

Much of the rest of our story is about how to get an innovation practice started with the resources, credibility, and leadership necessary to make it work, to make it successful. Anybody can start a skunk works. It’s harder to start an innovation team that works and gains rapid traction in a complex organization. Here we’ll place less emphasis on the facts and stories of our success and more on the “secret sauce” of how and why it works.

A Short History of CFI

The story of the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation starts in the Department of Medicine (DOM), the largest physician group within Mayo Clinic, under the leadership of Nick LaRusso, M.D., the department chair, and his administrative partner, Barbara Spurrier (also a coauthor of this book). Their team included, in particular, Michael Brennan, M.D., the associate chair of the DOM Outpatient Practice, and Douglas Wood, M.D., who was, at the time, the vice chair of the DOM and who is currently the medical director of the Center for Innovation. The DOM recognized a need for patient-centered innovation beyond the clinical innovations already being championed by Mayo’s Research arm. This innovation effort evolved in stages.

At the outset, in 2001, “to promote innovation” became one of six stated objectives in the DOM’s strategic plan. That objective called for the creation of a formal and dedicated design lab known as the See, Plan, Act, Refine, Communicate (SPARC) Lab. SPARC and other department initiatives were combined into a formal DOM program known as the Program in Innovative Health Care Delivery. SPARC was the showcase and flagship, and it turned in some of the early successes of applying a design thinking mindset and an innovation discipline. In the summer of 2008, the program was formalized in the broader organization, with the formation and launch of the CFI we know today.

Here are some highlights of the story.

An Early SPARC

In the early days, coauthor Nick LaRusso discussed the challenges facing Mayo and the patient experience with a small group of colleagues. They wondered, specifically, if the care delivery process could be subjected to methodical study, just as clinical care had been studied and advanced for some time. Some of the earliest discussions occurred between Nick and Michael Brennan, usually during their long runs together or afterward over a few pints of Guinness (usually provided by Dr. Brennan, a Dublin-born Irishman).

They saw the connection between what they were trying to do and what others outside the medical community, particularly in service industries, were attempting. That led to engagements and ultimately collaborations with outside specialists and consultants, most notably the design and innovation consulting team of IDEO but also HGA Architects and Engineers and Steelcase, the large office furniture company. Those relationships still exist today, and in particular CFI remains closely engaged with Jim Hackett, now former CEO of Steelcase, and Tim Brown, president and CEO of IDEO and author of Change by Design.

The core idea at the time and to this day was to evolve a design discipline, a design-centered way of thinking, into a health care organization. We’ll cover design thinking more in Chapters 4 and 5, but for now it’s enough to say that it incorporates a thorough and contextual analysis of true customer needs and an open-ended but disciplined approach to delivering innovations to benefit that customer.

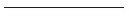

The DOM leadership team set up what they then referred to as a “skunk works” laboratory called SPARC (Figure 3.1). Started in 2002, the lab was staffed with four people, and it opened operations in a specifically designed and constructed practice space within the Mayo Building. It was at this time that coauthor Barbara Spurrier, then senior administrator for the DOM, entered the mix.

FIGURE 3.1. EARLY SPARC LAB

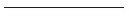

In its first years of existence, SPARC looked at patient flow, including how patients used waiting areas and exam rooms, how they interacted with providers, and how technology was deployed (Figure 3.2). The resulting innovations took on a redesign of patient exam rooms—expanding their size, doing away with sharp corners, and setting up computer swivel monitors so that both the physician and the patient could look at them from where they sat. They divided these Jack and Jill rooms into dressing, exam, and conference areas, set up properly for all three purposes (Figure 3.3). The hypothesis—and result—was that in these newly designed exam rooms, patients would feel more involved with their own care. Ditto for the decision aid documents explaining medical regimens and their steps—for example, diabetes care.

FIGURE 3.2. REDESIGNED EXAMINATION ROOM: BEFORE

FIGURE 3.3. REDESIGNED EXAMINATION “JACK AND JILL ROOM”: AFTER

SPARC’s early successes owed to the formalization of the innovation process, and especially of design thinking, and to the early credibility of leadership, coming directly from the Department of Medicine. Other physicians, seeing the success and the organization’s commitment, became “friends of SPARC,” and they became involved in early SPARC projects. Likewise, the formalization of effort led to a gift from an outside benefactor, which obviously helped move the concept forward more rapidly. The internal processes, combined with strong leadership and early organizational hooks, and emerging external influence were the secrets to early success.

At first we operated under the radar as does a typical skunk works, but even then the project had many of the seeds, including top organizational leadership and commitment, of a more formal program. The term skunk works originated from Lockheed Martin. A skunk works operation is created, and often self-created, with a high degree of autonomy, resources, and time usually off the books (with no formal staffing or budget), outside the bureaucratic realm (and often off the premises). It sometimes works on secret projects. Our project had some of those seeds too, but we quickly realized that to gain the organization’s commitment and support, particularly from the medical practices, our work would have to have a more formal and visible effort.

Maybe we were a skunk works, maybe we weren’t. We simply were trying new things and needed a protected environment in which to do so, and the DOM offered that cover. But we saw that better things would lie ahead, including buy-in from Mayo leadership and practicing physicians, if we became more visible.

We feel that the CFI that emerged is a hybrid—combining some of the best characteristics of a skunk works (a degree of autonomy, absence of strict hierarchy, minimal to no bureaucracy, and nontraditional processes) with the best features of a formal, embedded, fully staffed, highly visible, and “public” internal enterprise. It was the world’s first embedded design group to be integrated into a live medical practice, and it remains so today.

A Center for Innovation Is Born

SPARC was successful on two fronts. First, it brought useful and credible innovations in spatial design, patient processes, and patient communications to life. But second, and probably more important, it demonstrated the concept of an embedded design lab, with its patient-centered, design-enabled innovations, to the Mayo practice and culture.

The “C” in SPARC stands for “Communicate,” and that too became a big part of the success story. SPARC projects and successes were presented in various parts of the organization, brochures were printed, and a website was built to help followers track its activity. Physicians were brought in to see and participate in design prototypes, and they could also conceive and initiate projects within SPARC. These communication efforts played well with Nick LaRusso’s credibility within Mayo as chair of the DOM, and as time went on, SPARC caught the attention of the institution’s leadership and individuals outside the DOM.

Really, SPARC was a design prototype for the more formal patient-centered innovation organization that was to emerge. In 2007, discussions commenced with the Rochester board of governors and Mayo’s CEO and president at the time, Glenn Forbes, M.D., about a more formal, enterprise-wide, institution-wide effort that ultimately became known as the Center for Innovation. Dr. Forbes was a huge believer in the DOM’s Program in Innovative Health Care Delivery, and he encouraged the Mayo leadership to recast this effort as a broader organizational capability.

Barbara Spurrier joined the team as Nick’s administrative partner, as did coauthor Dr. Gianrico Farrugia, who was then leading an innovation effort for the Mayo Clinic Clinical Practice Committee. The advent of the CFI within the greater Mayo Clinic organization was announced at the first TRANSFORM symposium in September 2007—a Department of Medicine–sponsored internal/external showcase of innovation in the health care experience. The infrastructure was created, and the SPARC Lab was integrated into the formal launch of the Center for Innovation in June 2008.

As we move through this chapter, you’ll see what makes CFI unique among innovation groups and labs in other complex organizations, and what makes it work in the Mayo organization. It starts with the vision, which we will cover extensively, and the staffing, which we will also cover. You’ll see the uniqueness and clarity of our operating purpose, philosophy, and principles. You’ll see how we partner with key individuals and groups, both inside and outside of Mayo. And last but not least, you’ll see how we operate as a committed, embedded, public, visible, design-centered, and change-oriented enterprise.

The CFI Way: Philosophy and Guiding Principles

Like most other innovation teams in large, complex organizations, the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation faced many challenges from its inception. In Chapter 2, we laid out 15 reasons why large organizations can’t innovate or, at least, have a hard time doing so. We’ve also described throughout the inherent conflict between design-based innovative thinking and the conservative, risk-averse culture of the physicians we work with. Combine all this with the Mayo organizational “pinstripes”—its reputation, its committee-based approach to shared decision making, its pride in past and current success, and frankly, the “arrogance” of its success—and you have a difficult mix to work with as an innovation center.

Unless, of course, you lay the proper groundwork.

In the early days, we carefully considered—and really, thrashed around a bit with—form, structure, vision, and guiding principles for CFI. We wanted to create a culture and competency in which innovation could thrive, to position the CFI as a catalyst and igniter of innovation across the organization. We worked with the experts, who gave us insight into what works and what doesn’t. We visited with other health care and medical organizations, including Memorial Hospital in South Bend and Medtronic, and an assortment of innovation leaders from other industries including IBM, Procter & Gamble, Cargill, 3M, Steelcase, and IDEO. We read practically every book available on innovation, and we tested ideas with our constituents. We observed the successes and failures of our early efforts with SPARC and other initiatives. Finally, we created and fine-tuned (and we continue to iterate) a set of guiding principles. We share these eight principles, which evolved through experience, here and in Figure 3.4 to light the way (and there are more throughout the book):

FIGURE 3.4. CENTER FOR INNOVATION GUIDING PRINCIPLES

1. Build a discipline of innovation. The key word is “discipline.” Build it, live it, champion it throughout the organization.

2. Recruit a diverse team. Designers, project managers, and others from outside the world of medicine—for example, engineers, architects, product designers, and anthropologists—bring diverse backgrounds and thought processes. Combine them with scientists and organizational experts, and mix well and often.

3. Embrace creativity and design thinking. A customer orientation, experiments and prototypes, arts and sciences all converge. Failures are expected and tolerated.

4. Environments matter. Create open, Silicon Valley–style lab experimentation spaces that simulate real spaces. This fosters realism, collaboration, creativity.

5. Co-create with your customers and stakeholders. Involve practices at all levels in your projects. Provide platforms with which to incubate and accelerate your customers’ and stakeholders’ ideas, not just yours.

6. Organize around Big Idea platforms. All projects must fit the big picture and vision. Articulate and organize around the smallest number of big ideas.

7. Collaborate inside and outside. Bring in appropriate players from the practices, and also encourage outside participation, partnership, and sponsorship where it makes sense. No detached ivory tower labs here, please!

8. Consistently share your vision, process, and results. Communicate the vision and “transfuse” the principles and tools of innovation into the organization. Be visible, and be easy and useful to work with. This is the subject of Chapter 6.

These eight items comprise an evolving cultural blueprint that defines our ethos and permeates every action inside CFI. Every CFI team member gets it and lives it. It’s a signature by which we survive and thrive inside the Mayo community and, increasingly, in the outside world.

The CFI Way: Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast

Cannon Falls, Minnesota, is a small, quintessentially Midwestern town about halfway between Rochester and the Twin Cities. Its claims to fame are that (1) it is the site where Barack Obama kicked off his 2012 presidential campaign, (2) it is home to the Pachyderm Studio, a music recording studio used by Nirvana, among others, and (3) it is the site of Mayo Clinic’s first remote test of the eConsults platform, our evolving electronic pathway enabling remote physician-physician and physician-patient communications.

You probably haven’t heard of Cannon Falls, and we introduce it only to make a point. That point connects to another signature part of our operating culture, one that has risen in stature to become a trademarked operating philosophy and even to become a department motto and subbrand (Figure 3.5). It’s our book title as well: Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast.

FIGURE 3.5. THE CFI OPERATING PHILOSOPHY

Okay, so General Electric has “We bring good things to life,” and Coca-Cola has, “Things go better with Coke” and a stable full of others. What’s so special about a subbrand? A jingle? An “elevator pitch”? We’re not about to film TV commercials, so what’s the big deal?

The big deal is that, as part of our design and execution discipline, we always frame our activities with this concept. We “think big”—about things that really matter and lead to “putting a dent” in the health care universe. We “start small”—by not trying to do everything at once with a large-scale or complex implementation, hence our choice of a small, Mayo-operated clinic in Cannon Falls and an independent breast cancer clinic in Anchorage, Alaska, to try out our eConsults ideas. We “move fast”—to learn from our prototypes, sell into the organization based on those prototypes, and proceed toward larger-scale, iterative, staged implementations.

The importance of this framework is perhaps better illustrated if we look at what would happen if we didn’t use it:

![]() If we didn’t “think big,” we would never transform the health care industry. Our projects, while successful, wouldn’t amount to enough to garner attention or continued support. We would likely expend too much energy on trivial issues.

If we didn’t “think big,” we would never transform the health care industry. Our projects, while successful, wouldn’t amount to enough to garner attention or continued support. We would likely expend too much energy on trivial issues.

![]() If we didn’t “start small,” our projects would be too big and complex, implementation would be slow and uncertain at best and likely would never happen, and we wouldn’t be able to learn or demonstrate as we go. Programs would ultimately take too long and probably deliver suboptimal results. Innovation is as much about execution as it is about ideation.

If we didn’t “start small,” our projects would be too big and complex, implementation would be slow and uncertain at best and likely would never happen, and we wouldn’t be able to learn or demonstrate as we go. Programs would ultimately take too long and probably deliver suboptimal results. Innovation is as much about execution as it is about ideation.

![]() If we didn’t “move fast,” the greater organization would lose interest. Our own players would lose interest too—innovators like to see their innovations come to market. Ultimately we would lose the opportunity to lead the transformation.

If we didn’t “move fast,” the greater organization would lose interest. Our own players would lose interest too—innovators like to see their innovations come to market. Ultimately we would lose the opportunity to lead the transformation.

As a consequence, all of our projects must fit into the big picture of innovation that matters but be constructed small enough (or with small enough pieces) to get to a fast implementation or at least a rich prototype. We try to implement at least a major prototype within six months of a project launch. We’ll come back to these concepts throughout Part II of this book.

The CFI Way: Structuring for Success

When you think about establishing an innovation competency and an internal innovation capability within a large organization, it’s natural not to think too much about structure in the beginning. You think about ideas, scope, funding, staffing, spaces, culture—but not so much about the structure of the endeavor. For many, structure might seem contrary to the idea of letting ideas flow, and it might seem to be something that will sort itself out over time. We disagree.

The Importance of Structure

If innovation is a discipline, as we believe it is, then creating a structure is important from the very beginning. How do you structure the vision into neat compartments so that you can address them effectively? How do you structure projects into those compartments so that they aren’t off track or even contrary to the vision? Structure is important for any innovation investment, particularly in light of Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast. In fact, we don’t think you can really achieve Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast without an effective working structure.

And what do we mean by structure ? Structure isn’t about organization charts. Structure in this case refers to the organization of work. How do we align our programs and projects to accomplish the major goals, or platforms, of our transformative vision? How do we align other organizational resources to support these efforts and to “transfuse” our visions, our accomplishments, and the higher-level innovation competency into the rest of the organization? That’s what we mean by structure.

Organizing our work and our duties helps in three major ways:

![]() We build the right team with the right individuals.

We build the right team with the right individuals.

![]() Individuals within the unit see how activities fit together.

Individuals within the unit see how activities fit together.

![]() Others outside the group see the vision and fit, and they can see how to work with us.

Others outside the group see the vision and fit, and they can see how to work with us.

Perhaps the most important consequence is the last—having a visible structure allows all of our constituents and partners to see what we’re doing and how it supports the greater vision. The structure becomes a major part of any presentation of our capabilities and accomplishments.

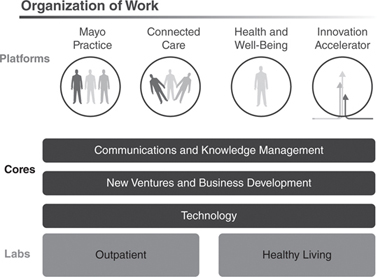

The CFI Organization of Work: Platforms, Cores, and Labs

The best way to illustrate “structure” is to show our own, one that has evolved over time. Figure 3.6 shows the essence of the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation through its structure. There is a guiding vision toward which all of this is aimed—to transform the health care paradigm into an “Always be there for me” continuous presence, both as part of ongoing “health” and the effective delivery of care during “health events” that health care is known for today. In other words, we play both in sickness and in health. That vision is described more fully in the next section.

FIGURE 3.6. CFI ORGANIZATION OF WORK

Isn’t the cart before the horse? Normally, wouldn’t we present the vision, then the structure required to execute on the vision? We’re trying a different approach—one that worked for us—in that the structure may explain the vision more effectively than vice versa. The point is, they both play together, and in fact, much iteration may be required to get both the vision and the structure right. Sometimes, structure will help define the vision. We think you’ll see this more clearly as you go through this and the next section.

Highlights of our structure include the following:

![]() CFI Platforms. CFI is organized around four platforms, or strategic opportunity areas for transformation : Mayo Practice, Connected Care, Health and Well-Being, and the Innovation Accelerator.

CFI Platforms. CFI is organized around four platforms, or strategic opportunity areas for transformation : Mayo Practice, Connected Care, Health and Well-Being, and the Innovation Accelerator.

![]() Mayo Practice. The Mayo Practice platform includes initiatives designed to improve the bricks-and-mortar facility-based patient care, in the outpatient or hospital setting. These initiatives include but aren’t limited to pre-visit, visit and post-visit processes, spatial design, information gathering and recording systems, and care instruction and learning tools. Parenthetically, the progress made as a result of the initiatives within this CFI platform will not be limited to the Mayo practice, but ultimately could be emulated by other care delivery organizations.

Mayo Practice. The Mayo Practice platform includes initiatives designed to improve the bricks-and-mortar facility-based patient care, in the outpatient or hospital setting. These initiatives include but aren’t limited to pre-visit, visit and post-visit processes, spatial design, information gathering and recording systems, and care instruction and learning tools. Parenthetically, the progress made as a result of the initiatives within this CFI platform will not be limited to the Mayo practice, but ultimately could be emulated by other care delivery organizations.

![]() Connected Care. Connected Care initiatives are, as the name implies, a series of tools enabling patient care without a physical presence in a facility, that is, outside of our bricks and mortar. Connected Care projects connect physicians and other care providers directly with patients, or they may connect local physicians with Mayo physicians for an advanced consultation. Connected Care projects incorporate networking and mobile technologies, and they may be directed toward general care or to specific diseases and chronic conditions.

Connected Care. Connected Care initiatives are, as the name implies, a series of tools enabling patient care without a physical presence in a facility, that is, outside of our bricks and mortar. Connected Care projects connect physicians and other care providers directly with patients, or they may connect local physicians with Mayo physicians for an advanced consultation. Connected Care projects incorporate networking and mobile technologies, and they may be directed toward general care or to specific diseases and chronic conditions.

![]() Health and Well-Being. Health and Well-Being concerns how to optimize the health and well-being of individuals and families. Well-Being pertains both to ongoing health and avoidance of care events. Health and Well-Being projects engage individuals to optimize their health and increase their capacity to make decisions that maintain or increase functional status.

Health and Well-Being. Health and Well-Being concerns how to optimize the health and well-being of individuals and families. Well-Being pertains both to ongoing health and avoidance of care events. Health and Well-Being projects engage individuals to optimize their health and increase their capacity to make decisions that maintain or increase functional status.

![]() Innovation Accelerator. The Innovation Accelerator platform includes programs to educate, incubate, and provide visibility to innovation across the Mayo organization. The platform includes an Internet-based tool to crowdsource ideas with Mayo Clinic employees and an incubator called CoDE (Connect, Design, Enable), which acts like an internal venture capital firm to select, fund, and assist with about 10 ideas per year originating in the practice. Also in this platform, the annual international TRANSFORM symposium provides both internal and external lift and visibility to CFI activities. We’ll cover the Innovation Accelerator platform in more detail in Chapter 6.

Innovation Accelerator. The Innovation Accelerator platform includes programs to educate, incubate, and provide visibility to innovation across the Mayo organization. The platform includes an Internet-based tool to crowdsource ideas with Mayo Clinic employees and an incubator called CoDE (Connect, Design, Enable), which acts like an internal venture capital firm to select, fund, and assist with about 10 ideas per year originating in the practice. Also in this platform, the annual international TRANSFORM symposium provides both internal and external lift and visibility to CFI activities. We’ll cover the Innovation Accelerator platform in more detail in Chapter 6.

![]() Cores. These include skill sets and services that support our programs and connect them with other parts of the organization or to the outside. Services like information technology, communications, and business development are brought in from their host areas within Mayo. Resources officially report to their local home area, which helps to create a distributed internal network, but these resources serve and are embedded in the CFI group.

Cores. These include skill sets and services that support our programs and connect them with other parts of the organization or to the outside. Services like information technology, communications, and business development are brought in from their host areas within Mayo. Resources officially report to their local home area, which helps to create a distributed internal network, but these resources serve and are embedded in the CFI group.

![]() Labs. These are the physical lab spaces where we experiment and prototype our new models. In addition to the administrative home of the CFI, we also have a separate Multidisciplinary Design Outpatient Lab, which has been constructed to simulate real outpatient environments and handle real patients as our prototypes require. We also operate the Healthy Aging and Independent Living Lab, a fully functional lab simulating a real living environment for seniors located in our Charter House, which is a continuing care retirement community (CCRC) owned and operated by Mayo. A new Healthy Living Lab is scheduled to open in early 2015, and it will be focused on testing and prototyping health and well-being services and products in the home and office environments.

Labs. These are the physical lab spaces where we experiment and prototype our new models. In addition to the administrative home of the CFI, we also have a separate Multidisciplinary Design Outpatient Lab, which has been constructed to simulate real outpatient environments and handle real patients as our prototypes require. We also operate the Healthy Aging and Independent Living Lab, a fully functional lab simulating a real living environment for seniors located in our Charter House, which is a continuing care retirement community (CCRC) owned and operated by Mayo. A new Healthy Living Lab is scheduled to open in early 2015, and it will be focused on testing and prototyping health and well-being services and products in the home and office environments.

These descriptions may seem a bit minimalist at this point, but we will come back to these platforms, cores, and labs throughout the book.

Our platforms help us organize our work, but again they wouldn’t be complete without a structure to manage our work. To do that, within each of the four platforms we define programs and projects :

![]() Programs. These are major strategic efforts within the platform usually aligned to a certain care segment or technology base for the activity. Programs include related projects managed in a coordinated way to achieve greater benefit and efficiency than managing them individually. Within Connected Care, we have the eHealth (network communications) and mHealth (mobile) and condition-specific programs like our connected support platform (OB Nest) for pregnant mothers-to-be and our support program for diabetes. Health and Well-Being programs include Thriving in Place projects for the elderly, Student Well-Being for Learning and Life, and community projects designed to improve health and coordinate resources in the community. The Mayo Practice platform has a large program called the Mars Outpatient Practice Redesign that looks at significantly enhancing efficiency and reducing cost in the specialty practice. The Innovation Accelerator includes the dynamic CoDE program with a continually changing portfolio.

Programs. These are major strategic efforts within the platform usually aligned to a certain care segment or technology base for the activity. Programs include related projects managed in a coordinated way to achieve greater benefit and efficiency than managing them individually. Within Connected Care, we have the eHealth (network communications) and mHealth (mobile) and condition-specific programs like our connected support platform (OB Nest) for pregnant mothers-to-be and our support program for diabetes. Health and Well-Being programs include Thriving in Place projects for the elderly, Student Well-Being for Learning and Life, and community projects designed to improve health and coordinate resources in the community. The Mayo Practice platform has a large program called the Mars Outpatient Practice Redesign that looks at significantly enhancing efficiency and reducing cost in the specialty practice. The Innovation Accelerator includes the dynamic CoDE program with a continually changing portfolio.

![]() Projects. Finally, we get to the list of 100-plus projects that fit under the programs just outlined. These projects are tactical, temporary, and may or may not be active at any given time. They are all in various stages of completion, and they may go inactive for periods of time as resources and testing schedules dictate. The project list includes the practice-originated CoDE projects awarded and supported each year. This structure for projects was far from finalized when we established CFI. It has evolved as our vision has evolved, as project ideas have flowed in, as the needs of the business have changed, and as we have grown. Indeed, the current structure is Version 2.0 of the CFI, and the current projects are enumerated in Appendix B. The listing of all Mayo Clinic Practice Partner Departments since the CFI’s inception is presented in Appendix A.

Projects. Finally, we get to the list of 100-plus projects that fit under the programs just outlined. These projects are tactical, temporary, and may or may not be active at any given time. They are all in various stages of completion, and they may go inactive for periods of time as resources and testing schedules dictate. The project list includes the practice-originated CoDE projects awarded and supported each year. This structure for projects was far from finalized when we established CFI. It has evolved as our vision has evolved, as project ideas have flowed in, as the needs of the business have changed, and as we have grown. Indeed, the current structure is Version 2.0 of the CFI, and the current projects are enumerated in Appendix B. The listing of all Mayo Clinic Practice Partner Departments since the CFI’s inception is presented in Appendix A.

Our platform, lab, and core structures have all grown as we’ve become a more mainstream Mayo entity. Our platforms have become more defined and clear—we started with five in 2008, and now we have four, each with a robust portfolio of programs and specific projects and metrics. Based on our experience, we recommend establishing a structure as soon as possible to start an innovation function, to be evolved as need be.

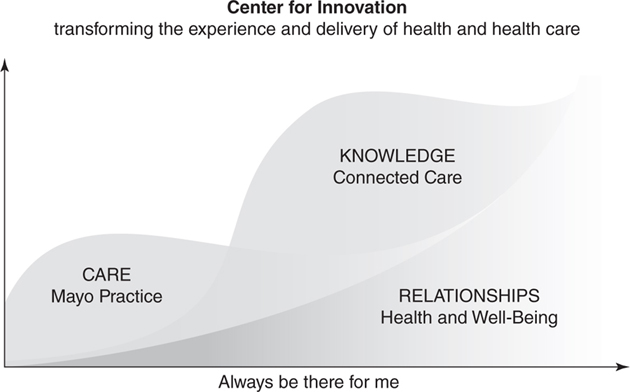

The CFI Way: Vision for Success

Now, at last, we arrive at the guiding vision for the Center for Innovation, and really, the guiding vision for the overall transformation of health care into a 21st century model of care. All the history, structure, and context you’ve read so far have led to this vision; this vision in turn guides everything we do.

The vision can be stated most succinctly: “Always be there for me.” Now that may be a bit too high level to grasp or to put into action, but it really speaks to a long-term relationship between the individual and the organization, a relationship that transcends that of being a series of transactions and events to becoming a lifelong partnership. If that seems odd, just think about the companies and industries that work hard just to have a relationship with their customers that extend beyond fixing a product when it breaks, like the relationships we see in the auto industry.

Vision: Always be there for me.

We think we can provide a better experience and better health outcomes—with more patient comfort and lower cost—if we have a continuous relationship with the customer, enhanced by technology and powered by a Mayo team. It is no longer “get sick, go to the doctor.” The new model is continuous care, available in a “fast, friendly, and effective” manner at all points of contact.

At a slightly more detailed level, we also express our vision as “Health and health care, here, there, and everywhere.” It is about health, not just fixing health problems. It is about ongoing health and maintenance, and it can be delivered anywhere—on a mobile device or remotely by a care team in a real-time consultation from multiple locations. With current and future technologies, we can render a majority of bricks-and-mortar office visits obsolete, instead connecting health and care to individuals where they live and work.

All of our platforms, programs, and projects go to support the idea of broadening health care beyond the acute care event, getting what we can out of the hospital and doctor’s office, and transforming what does require a doctor’s office or other facility into a better experience. It all leads to our mission:

The Mission:

Transform the delivery and experience of health and health care.

From Only Here to Here, There, and Everywhere

Okay, that’s nice, but how do we get there? How do we execute an orderly transition, a transition from today’s facility-centered, break-fix medical treatment paradigm? We’ve thought that one through too.

The chart in Figure 3.7 maps the evolution of the 21st century model of care over time—not coincidentally, through the three major CFI delivery platforms: Mayo Practice, Connected Care, and Health and Well-Being.

FIGURE 3.7. CFI VISION: THE 21ST CENTURY MODEL OF CARE

The x axis, of course, is time. We see a gradual but persistent evolution into the 21st century model. That evolution takes us beyond health care to just plain health. It also moves the center of gravity away from the physician’s office and hospital to the patients in their homes and communities.

Initially, we improve the patient experience within the Mayo Practice. Improved outpatient facilities and workflows, hospital experiences, patient knowledge, and a better balance of staff make the process more “fast, friendly, and effective” to those who visit the doctor. It is today’s care model, remixed and enhanced. As time goes on, we build our Connected Care capabilities, enabling us to connect through technology with patients at any point in the maintenance and care cycle. As these technologies are developed, refined, and diffused, the Mayo Practice “here” remains part of the transformation, but more of the care is delivered through technology, thus, “there” and “everywhere.” Finally, we develop the well-being and healthy living concepts that transcend care over time; with Connected Care, many of these too can be delivered “there” and “everywhere.”

The net result? We get to the right balance of health and health care. We like to refer to it as “changing the rhythm of care.” This is the essence of the transformation to the 21st century model of care.

And when will this happen? We are currently targeting 2018 as the year to reach this balance.

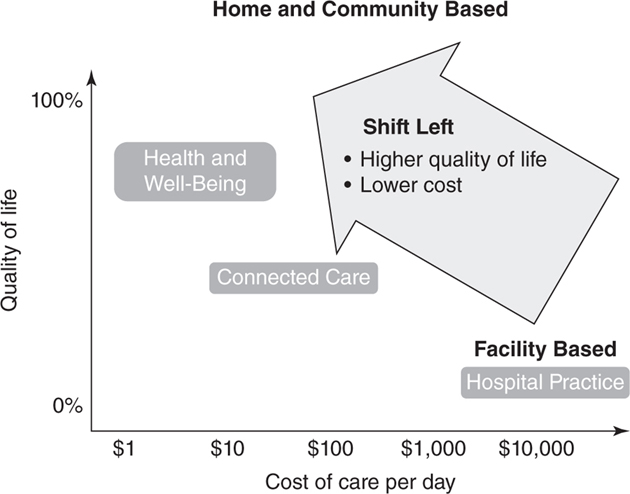

A Shift to the Left

As another way to illustrate this multidimensional transformation, we often refer to our “Shift Left diagram,” presented in Figure 3.8. The chart, like the one in Figure 3.7, shows a gradual transformation toward health and wellness management, using Connected Care tools, and away from traditional health care delivery at medical facilities. The shift improves the quality of life while reducing the total cost of care.

FIGURE 3.8. A SHIFT TO THE LEFT

The CFI Way: Spaces for Success

Now we move from the conceptual aspects of building the Center for Innovation to the more “real” ones—in this case, the facilities and labs of CFI. We believed from the beginning that “innovation needs a special place.”

While many innovation efforts, particularly those of the skunk works variety, make do with the spaces they have—often some bit of unused space in an existing facility, or even leased space somewhere outside the operative mainstream of the enterprise—we felt from the beginning that it was important to have the right kind of space in the right location. Dating back to our SPARC roots, we believed that our space needed to have the look and feel of a design center and that it needed to be deeply embedded and as central as possible to the practices and the individuals for and with whom we innovate. By “design center look and feel,” we wanted open, contemporary, and collaborative spaces that fostered creativity and led to the sort of team building and informal networking we feel are vital to the exchange and development of ideas. “Watercooler” discussions were, and still are, very important to us.

Gonda 16

Our original space was designed with the help of IDEO and Steelcase, the latter providing much of the furniture for our original SPARC Lab and what became our central Gonda 16th-floor design facility and headquarters (Figure 3.9). The 10,000-square-foot facility is embedded in the geographic center of Mayo Clinic’s medical practice. The office arrangement has evolved, but it is still characterized by open offices with adjacent and facing desks to facilitate collaboration, plenty of conference rooms with large tables and glass walls, and the latest in computer and display technology.

FIGURE 3.9. GONDA 16 CFI HEADQUARTERS

If you walk into today’s Gonda 16 facility, you’ll see the “writing on the wall” in the form of whiteboards and writing on the glass walls and windows echoing various conversations among the team members. The open spaces, glass walls, Post-it Notes, and project summary posters facilitate collaboration and transparency between projects. Team members can see each other’s work—literally—and they feel involved with each other. There’s room to display and work on prototypes, and prototyped technology solutions like Connected Care projects are easy to see and experience.

We call it “space that doesn’t get in the way” of our innovators, and it is space that does not form a barrier between us and our stakeholders and practice constituents. The “front stage” of the space is open to any Mayo Clinic employees to use, even if they are not working with CFI, simply to allow them to experience the space and conjure a “thinking differently” mindset. Our space is important, but it is by no means exclusive to our use, and it has become popular as a Mayo Clinic showcase, and it forms a key part of the fabric of our existence.

Multidisciplinary Design for the Outpatient and HAIL Labs

In addition to design space, it is also important to have spaces to research the patient experience and to prototype new models. It has to be done in spaces that are as realistic as possible for the patients and that are set up for proper observation of old and new behaviors. For this research we have two dedicated labs, and we make use of other settings as well.

The Outpatient Lab, known formally as the “Multidisciplinary Design Outpatient Lab,” is located on the 12th floor of the Gonda Building (Figure 3.10). Furniture and walls are movable, wall décor is magnetized to allow changes in look and feel, and the technologies are flexible and can be set up to simulate real interactions while allowing data collection by observers. All aspects of a clinical visit can be simulated with real patients, from waiting room to check-in to exam room activities.

FIGURE 3.10. GONDA 12 OUTPATIENT LAB

As noted earlier, CFI also operates a senior living lab known as the Healthy Aging and Independent Living, or HAIL, Lab (Figure 3.11). The lab, operated in partnership with the Robert and Arlene Kogod Center on Aging, is physically located in the Charter House, a continuing care retirement community of 400 residents, which is adjacent to the main Mayo campus in Rochester. The lab is configured as a set of retirement community apartments, each with a full living room, bedroom, bath, and kitchen as well as central dining facilities and a nursing station. It is set up to test and prototype “aging-in-place” programs within the Health and Well-Being platform, and it has been used by outside organizations for various research projects.

FIGURE 3.11. HEALTHY AGING AND INDEPENDENT LIVING (HAIL) LAB

In addition to the prototype lab spaces, we routinely go to the patients for observation and ethnographic understanding. For example, if we are researching the inpatient experience, we hang out with patients and their loved ones in the hospital and even transition with them to their homes to understand the whole experience. A designer and anthropologist might embed themselves for months in a Minnesota town to understand health from the perspective of community residents. Or designers might embed themselves on a college campus, as they did at Arizona State University, to understand the needs of students as they try to manage significant stress and optimize their health.

The CFI Way: Staffing for Success

The Center for Innovation is a dedicated, multidisciplinary, embedded team sitting right at the intersection of design and medicine. As such, we have staffed the organization with a diverse set of individuals from inside and outside the health care industry, individuals who bring a broad set of skills and motivation to our design and program management. People who join our group like new ideas and change and are uncomfortable with the status quo. They can tolerate ambiguity and the messiness of innovation, and they can synthesize the lessons of the outside world with the realities of medicine to produce results.

Over time we have grown the group from its early SPARC days of 4 people to a team of 60 with the following distribution:

![]() Service designers (14)

Service designers (14)

![]() Innovation coordinators (5)

Innovation coordinators (5)

![]() Administrative assistants (4)

Administrative assistants (4)

![]() Clinical assistants (4)

Clinical assistants (4)

![]() Project managers (13)

Project managers (13)

![]() Platform managers (4)

Platform managers (4)

![]() Technology analysts and programmers (5)

Technology analysts and programmers (5)

![]() Physician leaders (5)

Physician leaders (5)

![]() Business development manager (1)

Business development manager (1)

![]() Medical and administrative directors (2)

Medical and administrative directors (2)

![]() Operations manager (1)

Operations manager (1)

![]() Design strategist (1)

Design strategist (1)

![]() Others (not dedicated) from nursing, legal, systems and procedures, media support services, and human resources

Others (not dedicated) from nursing, legal, systems and procedures, media support services, and human resources

We also have embedded core resources, including a business development manager, IT specialists, communications staff members, project managers, graphic designers, and media specialists. And of course, the group includes health care team members such as nurses, physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and clinical assistants.

As mentioned, we pride ourselves on our diversity of skills and experiences. Our people are unique in many ways when compared to Mayo Clinic employees—they are younger, more are women, and they tend to be on more mobile career tracks. About 50 percent of our personnel come from outside the health care industry. We brought in such diverse talents as an architect, an anthropologist, a fashion designer, an ethnographer, and a former IBM peripheral manufacturing engineer. We feel strongly that these different disciplines add to our capability to frame and solve problems and to create truly human-scale experiences.

It’s also worth mentioning the cultural ethos of our team. While the job roles and department structures are carefully defined, we do operate in a looser, more informal, “watercooler” kind of way than do a lot of other organizations and even the departments in the rest of the Mayo Clinic organization. We limit the hierarchical structure and bureaucracy, and we offer autonomy and flexibility to our individuals wherever possible. Everyone is on a first-name basis; our workspaces are open, and our communications are open and informal whenever possible. Our space is comfortable—both for our own workers and for those in the greater organization or outside who choose to visit. The emphasis is on collaboration and tasks, not structure and formalities.

The CFI Way: Partnering, Networking, and Outreach

In nearly any business enterprise, partnerships serve to expand the resource and knowledge base available to accomplish the task. The exchange of ideas and the sharing of resources typically allow both partners to accomplish more than they could without the partnership. It’s all about finding “win-win” partnerships to accelerate the pace and strategically share resources, intellectual property, and/or branding.

We at Mayo have embraced the notion of partnering particularly with our larger innovation programs. We know that we have brand value to offer, and in some cases, we can offer innovations and solutions that our partners can use or even eventually license, which brings in a revenue stream for Mayo. Partners can help with funding, intellectual property, and experience of their own, and in some cases, they may provide settings to test and advance our programs.

Our partners come from the commercial, nonprofit, institutional, and academic sectors, mainly in the United States but some from overseas. In some cases, we form collaborations with a specific enterprise, as we did with Cisco for the eConsult program. In others, we form consortiums of partners who offer different resources and expertise, as we did with the HAIL Lab program. The HAIL Consortium is currently a group of four partners from different industries bringing in diverse resources and experiences:

![]() Best Buy, the electronics retailer, a founding partner

Best Buy, the electronics retailer, a founding partner

![]() Good Samaritan Society, with senior services and facilities in 240 communities across the United States

Good Samaritan Society, with senior services and facilities in 240 communities across the United States

![]() UnitedHealthcare, the largest health insurance carrier in the United States

UnitedHealthcare, the largest health insurance carrier in the United States

![]() General Mills, one of the world’s largest food companies

General Mills, one of the world’s largest food companies

In the HAIL example, the consortium connects frequently to establish the HAIL strategic direction and determine the experiments and investments, leading to customer insights that help all the organizations accelerate their product and service innovation and commercialization. The consortium meets formally twice a year to review results and identify future strategies.

The CFI Way: The Fusion Innovation Method

At this point it’s time to mark the transition from the why and who to the how. How does the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation approach the complex task of bringing about transformative innovation? Now that we understand the 21st century model of care, and some of the internal and external roadblocks to innovation, and how we set up CFI to address those roadblocks, how do we actually get there?

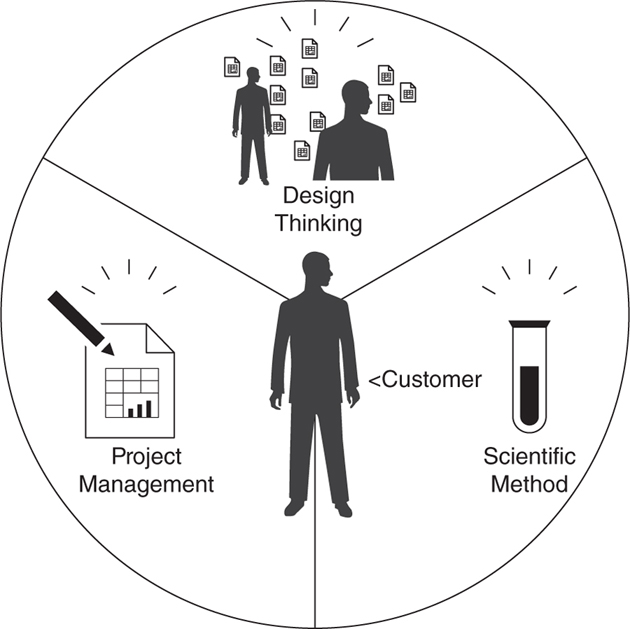

Part II of our book explains the how-tos, while Part III goes into greater depth with examples and recipes to help you emulate our success. As a way to get started, here we present the building blocks to what we ultimately call the Fusion Innovation Model, depicted in Figure 3.12, as part of the Mayo Model of Innovation.

FIGURE 3.12. FUSION INNOVATION MODEL

Now—deliberately so—there isn’t a lot of rocket science in this innovation model. But it provides a guiding context and a balance among disciplines that we feel are necessary for success. For example, we don’t want to go overboard with technology. Technology can often be a “solution looking for a problem,” a panacea that is shiny and compelling but if not handled properly and in the greater context of innovation, can waste a lot of time and energy. Technology should support a strategy. It is not strategy in and of itself. We view technology as a necessary but not sufficient enabler for transforming the experience and delivery of health care.

So technology is a given, a necessary enabler for what we do—you can’t have technology without a strategy, and generally you can’t have a strategy without some enabling technology. The customer, of course, is at the center of everything we do—and more often than not, the patient is the primary customer in mind. That said, customers can also be providers, staff members, payers, and other players in the system.

That leaves three critical elements in our innovation model:

![]() Design thinking. We’ll expand on this in the next chapter, but design thinking means using a deep understanding of the customer to frame a problem and then applying a methodical creativity to generating insights to solve it.

Design thinking. We’ll expand on this in the next chapter, but design thinking means using a deep understanding of the customer to frame a problem and then applying a methodical creativity to generating insights to solve it.

![]() Scientific method. The scientific method in this context is a rational, rigorous, data-driven, structured approach based on hypothesis, experimentation, and logical conclusions. Success must be demonstrated through a series of design and test cycles before taking an idea to market. Following these steps is especially important for our physician constituents in the practices.

Scientific method. The scientific method in this context is a rational, rigorous, data-driven, structured approach based on hypothesis, experimentation, and logical conclusions. Success must be demonstrated through a series of design and test cycles before taking an idea to market. Following these steps is especially important for our physician constituents in the practices.

![]() Project management. Finally, a rigorous project management discipline involving strong leadership and communication is critical to the success of the innovation model.

Project management. Finally, a rigorous project management discipline involving strong leadership and communication is critical to the success of the innovation model.

So now we’re at the point where the rubber meets the road. In the largest sense, our innovations apply technology and process to do something important for the customer. But—how do we get from here to there? What do the customers need? What new technology or process should we provide? How can we make sure that the approach we take truly solves the problem? How can we be sure to build it in such a way that it works and fits our overall vision? How can we make sure it’s delivered on time?

That’s where the three elements in Figure 3.12—design thinking, scientific method, and project management—really come together. In fact, as we’ll see, in our view they’re inseparable.

As a consequence, we’ve “fused” these three elements into a combined approach to delivering innovation that we call the Fusion Innovation Model. We recognize that good ideas aren’t worth much if the organization can’t move them forward. The Fusion Innovation Model centers on the customer, but it deploys a rigorously balanced discipline of design thinking, scientific method, and project management to turn them into reality. This balance helps us stay on course to provide the best results for every project and to deliver those results to the organization. Chapter 4 covers the Fusion Innovation Model.

Innovation the Mayo Clinic Way: Creating an Innovation Ecosystem

We don’t offer summaries at the end of every chapter, but we thought here it would be wise to wrap up some of the key ideas of CFI (and for establishing your own CFI) as a jumping-off point into the more process related material that follows. These are some of the highlights:

![]() Embedded, physically and metaphorically. Tight connections need to exist between the CFI and the operating parts of the business—in our case, between CFI and the Department of Medicine, for example.

Embedded, physically and metaphorically. Tight connections need to exist between the CFI and the operating parts of the business—in our case, between CFI and the Department of Medicine, for example.

![]() Credible leaders from the start. The head of the Mayo CFI was the top leader from the largest department within Mayo, and all leaders had significant institutional credibility.

Credible leaders from the start. The head of the Mayo CFI was the top leader from the largest department within Mayo, and all leaders had significant institutional credibility.

![]() Clear-eyed view of purpose. Without purpose, you have no program, and without a program, you have no innovation. State your purpose and principles, and make them everyone’s guiding light.

Clear-eyed view of purpose. Without purpose, you have no program, and without a program, you have no innovation. State your purpose and principles, and make them everyone’s guiding light.

![]() Design thinking. Structure creativity toward achieving a deep understanding of the customers’ needs.

Design thinking. Structure creativity toward achieving a deep understanding of the customers’ needs.

![]() Diverse team members. The CFI team was drawn from a wide and deep mix of designers and operations experts with outside training and credentials.

Diverse team members. The CFI team was drawn from a wide and deep mix of designers and operations experts with outside training and credentials.

![]() Establish a guiding EAC. This is not just a steering committee. It is a group of people who can add expertise and alliances. Note that “E” stands for “external,” not “executive.”

Establish a guiding EAC. This is not just a steering committee. It is a group of people who can add expertise and alliances. Note that “E” stands for “external,” not “executive.”

![]() Inoculating the organization. Transfuse the seeds of innovation throughout the organization by providing resources, communications, and a point of view about innovation.

Inoculating the organization. Transfuse the seeds of innovation throughout the organization by providing resources, communications, and a point of view about innovation.

![]() Structure. Establish a working structure aligned to the CFI vision in the beginning, and then evolve it as necessary, building the organization and its communications around that vision. Structure is important.

Structure. Establish a working structure aligned to the CFI vision in the beginning, and then evolve it as necessary, building the organization and its communications around that vision. Structure is important.

![]() Strategic partnerships. Never underestimate who might want to partner with you and what they might have to offer. Partnerships can provide anything from funding to expertise to filing cabinets.

Strategic partnerships. Never underestimate who might want to partner with you and what they might have to offer. Partnerships can provide anything from funding to expertise to filing cabinets.

![]() Balance. Don’t overdose in panaceas—for example, technology (“Let’s put everything on the Internet”) or project management.

Balance. Don’t overdose in panaceas—for example, technology (“Let’s put everything on the Internet”) or project management.

![]() Fun! Innovation, when done right, can be very fulfilling, engaging, and exciting. Take a tour of our CFI, and you’ll see what we mean.

Fun! Innovation, when done right, can be very fulfilling, engaging, and exciting. Take a tour of our CFI, and you’ll see what we mean.