CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER SEVEN

Leadership in Transformation

The Story of CFI 2.0

Innovation is fostered … by journeys into other disciplines … from active, collegial networks and fluid, open boundaries. Innovation arises from ongoing circles of exchange, where information is not just accumulated or stored, but created.

Originally, during our frequent meetings to plan this book, we wanted this chapter to be about how we manage the Center for Innovation. It was originally intended to give you the full picture of how we manage an innovation organization, from top to bottom, from motivation and hiring to results measurement and rewards. It was to be about the nuts and bolts of moving a large innovation team forward within a larger complex organization.

As we began writing, we found ourselves to be less excited about how we got to where we are today and way more excited about where we are going. So we’d like to scrap that construct and do something different.

We’ve shared how CFI came about. We’ve shared the industry state (the “problem”) and the vision (the framework of the “solution”) throughout the book and especially in Chapter 3. All of that has provided a solid backdrop for our work. We’ve also shared some of our successes against that backdrop, and we will share a few more in the next chapter.

We’ve had the usual challenges faced by other managers of embedded innovation teams. We’ve had to manage people. We’ve had to manage the natural tensions between design and science, between creativity and risk. We’ve had to manage large budgets, measure results, and justify our existence. We suspect that’s not much different from the experiences of everyone in our reading audience.

We’ve already described our path to our present state. In this chapter we’d like to talk more about leadership than management per se. We’d like to talk about the transformation of our leadership style.

That transformation of our organizational model, dubbed “CFI 2.0,” was borne out of a combination of our own experiences and of the insights provided by our experts and closest trusted advisors—our External Advisory Council team. With their insights we’ve transitioned to a new and evolved leadership model—which we’re pretty excited about and feel could be central to designing the leadership model for your organization too.

So that’s what we’ll do. We’ll talk about how we’re “innovating innovation”; how we’re transformed to a new, more collaborative, more fluid leadership style. We’ll talk about how we evolved from a more traditional functional management structure to a more self-directed “village” approach to leading the organization—really, to expanding collaboration and letting the organization lead itself. It’s an exercise in a more fluid, autonomous, self-directed approach to moving the team forward—and we think it will extend our Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast identity and style.

If It Ain’t Broke, Should We Fix It?

All in all, we think we’ve done a pretty decent job getting to where we are. We’ve built a great team. We’ve built a vision and platforms and projects within that vision. We know how to get results. We know how to share those results—and the ethos of what we do—through the transfusion mechanisms described in the last two chapters. We’ve established credibility inside Mayo Clinic. We’ve established credibility at a strategic level by recently elevating innovation to a core strategic requirement of the organization. We’ve established credibility at an operational level by creating a distributed model and weaving innovation into our fabric. And we’ve established credibility in the outside health care world.

Really, we don’t have much to complain about.

Since its formal inception in 2008, CFI has grown pretty big pretty fast. We’ve done a lot of things well, although, as expected, not always perfectly from the first steps. Every organization has change, some self-directed, some induced or inflicted from the outside. Every successful organization learns and adjusts as it goes, and we’ve done a lot of that. In our book that’s a good thing. We don’t want to be resistant to change or to get bogged down in the tentacles of tradition.

Despite these successes we decided to transform our innovation model into CFI 2.0. For us, change is good. Not just for the sake of change, but for the sake of moving forward. We have always been uncomfortable with the status quo.

Before describing the changes effected by CFI 2.0, it makes sense to review some of our major successes that we wanted to build upon.

Establishing the Vision

We have a vision. In fact, Mayo Clinic has one vision that can be summed up as “Health and health care, here, there, and everywhere.” As described in Chapter 3, we view health and health care in a longitudinal way—“in sickness and in health,” as the saying goes. We view the provision of health care as something that happens not just as a discrete visit when sick but also as a continuous connection or “tethering” in wellness. That tethering can also streamline care in sickness through electronic connectivity tools that bring patients in contact with providers—and specialist providers in contact with primary care providers—remotely, anywhere, anytime.

In other words—health and health care—when I need to come to you, when you can come to me, when I never knew I needed you.

The vision is really our centerpiece and our core. From that vision we built CFI’s four major platforms: Mayo Practice, Connected Care, Health and Well-Being, and the Innovation Accelerator. The vision has worked well, both internally and externally, as a centerpiece for communication, guiding our innovation teams, and nurturing our innovation activities.

Building the Team

We adopted the principles and methods of design thinking early on to build our CFI team. Those principles created considerable interest among our current—and our potential—employees. Who would have thought a big health care machine like Mayo Clinic would hire professional product designers? Anthropologists? Architects? Fashion designers? We did, and we deliberately hired people with diverse experiences from diverse walks of life to work with us full time, to be embedded in our practice, to integrate with the Mayo mystique, and to influence it from completely different perspectives.

The results have been amazing—a true win-win. They’ve learned from us, and we’ve learned from them. The interdisciplinary teams we’ve embedded have worked well. Everyone approaches our health care challenges with passion and a combined spirit that, we believe, leads to far greater productivity than would be the case if we hired designers only on a consulting basis.

In addition to a solid team, we feel we’ve built a solid culture—a culture that embraces the customer, a culture that is creative, a culture that embraces change, a culture that gets things done. “Real artists ship” is the timeless quote from Steve Jobs. We feel that we have real artists who can and will create a new health care experience and that we deliver.

Establishing the Metrics

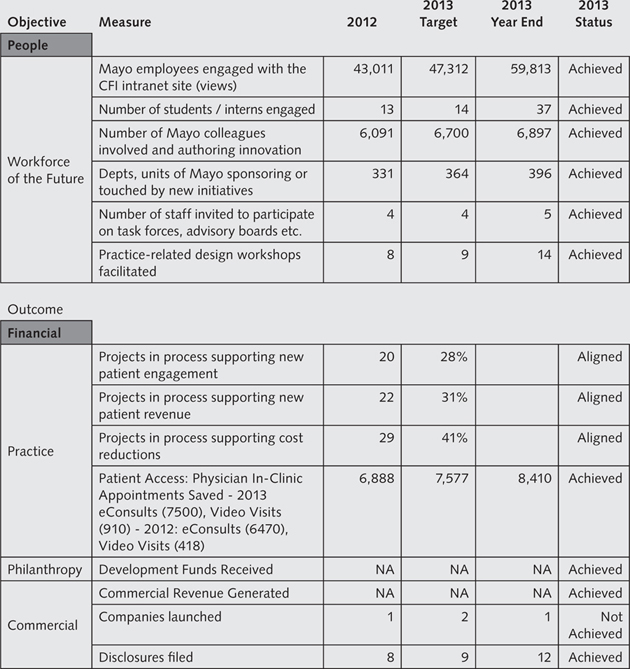

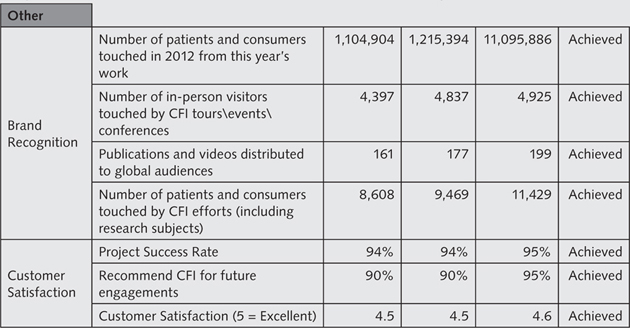

As any viable and accountable organization should, CFI has a set of core metrics. Like the metrics used by any organization, these have evolved over time, and as you might expect from our scientific approach, we are driven by metrics. Here are our three core metrics:

1. Time to first completed prototype. You’ve heard and embraced Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast. As you can see from this metric, and its placement as the first one, dexterous speed is very important to us. Choosing the metric of time to first completed prototype was also deliberate. The prototype is often the first time when our Mayo collaborators have an “aha” moment—they see the possibilities. Getting to that point is critical. In our organization the next big thing always demands everybody’s attention. We know, therefore, that if we’re going to keep people’s attention on the task at hand, we have to get to the first completed prototype as quickly as possible. But there’s also an important subtext here. We need to move fast to deliver the change needed and expected by our constituents, and—importantly—we know we can trust our teams to do it right even within the context of “speed is the number one goal.” Without the right kind of leadership and culture, teams would fail with such a mandate—the pressure to “move fast” would overcome the imperative to do it right.

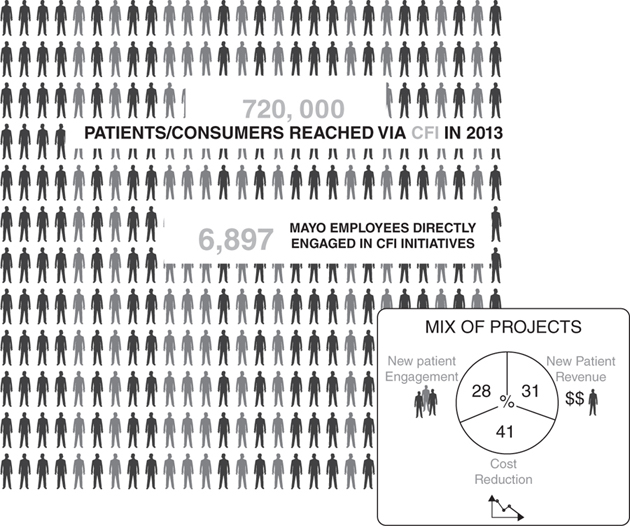

2. Number of patients’ and persons’ lives touched and impacted. This big-picture metric is important, for it is a barometer of whether we really make a difference, whether we really are delivering transformative change. If we focus merely on a few specialties and/or small sustaining innovations, will we transform health care? Probably not. So this metric is key—as is the stated Mayo Clinic goal of yearly touching 200 million lives by 2020. We estimate that CFI touched 720,000 lives (patients and consumers) in 2013. While this is still quite a bit short of the stated 200 million organizational goal, it is highly energizing to our teams, our constituents, and our leadership. That said, we also measure how deep we touch a patient’s life. The Pediatric Phlebotomy Chair did not impact many thousands of lives, but it had a big impact on those it did touch. As we outlined in the Introduction, it too met our definition of a transformative innovation. So we measure both numbers and impact.

3. Return on our investment (ROI). Despite the fact that we’re a not-for-profit entity, we must justify and pay for our existence as does any other organization. As we already stated, Mayo Clinic needs to invest hundreds of millions each year in research and education. Every project is evaluated for its revenue stream and cost impact on the practices and on Mayo Clinic as a whole. Projects are grouped by their primary purpose (new patient engagement, new revenue, cost reduction), and one of our measures of our effectiveness is revenue generated or expenses reduced—that is, the projected financial impact on Mayo’s practice.

The example in Figure 7.1 of how we show our metrics comes from a presentation we gave to the Mayo Clinic Clinical Practice Committee. Although the graphic presented is intended to “sample” our metrics, that is, how we view them and how we present them, you can begin to get an idea of the size and scope of some of our projects. Incidentally, in Chapter 8 we’ll cover a few projects—Mars, Optimized Care Teams, and eConsults—that support a major financial goal to reduce outpatient practice expenses by 30 percent.

FIGURE 7.1. CFI METRICS SAMPLER

Catalyzing the Process

From the beginning, we were big believers in the disciplines of design thinking, scientific method, and project management. Over time we developed those disciplines and infused them into the CFI team using a more or less traditional management approach. We sponsored and conducted training, assembled resource materials, deployed metrics, and created vehicles such as the CFI Project Control Book and the CFI Portfolio Roadmap to manage and balance our portfolio and keep it moving forward.

Over time, and quite naturally, designers became the stewards of design thinking, project managers became the stewards of project management, and we all became stewards of the scientific method. Our designers reported to a design lead, our project managers reported to a project management lead, and so forth. However, quite frankly, this structure catalyzed silos, not integration; it caused problems; it limited the value that individuals from one group could see in what individuals from another group brought to the innovation process.

As described in Chapter 4, we sought a better way, a better and more balanced approach to innovation. We sought a model in which every member of the team, management included, treated the innovation method as a singular, fused model, which you now know to be called the Fusion Innovation Model. All projects and programs would be managed forward by all people on the teams with a balance, an innate and natural emphasis on all three disciplines. Essentially, we fused the people just as we fused the disciplines.

The idea of the fusion model was not only to make sure all three disciplines were incorporated into a project effort but also to reduce friction within the teams. If everyone on the team lives and breathes all three disciplines, little time will be wasted addressing a dearth of scientific method or an overemphasis on design thinking or a failure to keep constituents updated. Projects could move forward in balance, without the friction created by team member “agendas,” by the natural tensions between creativity and deadlines, between data and intuition, and between customer and process. Popular stereotypes go away—for example, designers not being able to keep deadlines or project managers rushing the user research to get to the next stopgate or checkpoint.

In creating this model, we really manage a team of “specialist-generalists”—people contributing a distinct specialty expertise such as design or IT skills but who also function very well in other roles. When team members remain siloed into a single discipline or specialty, it requires the work of other team members—and often the resolution of tensions and conflict—to move things forward. We feel, from our experience, that any innovation team is well served—and easier to manage—if team members are conditioned and rewarded for a fused and holistic approach to their jobs. From the early days of CFI, we’ve emphasized the development of team members as generalists in addition to being the specialists they were when they joined the team. We prefer that individual members think of themselves first as innovators and second as designers or project managers or scientists.

We should also note the idea introduced in Chapter 3 that informality and trust are very important ingredients of our management style. We’re not talking about dress code here—Mayo expects a certain level of attire, and as an embedded organization, we’re quite compliant with that. But we have also adopted the open-floor and open-door attitude of many of our technology peers. There is little in the way of organizational hierarchy; everyone is on a first-name basis, and informal conversation is encouraged throughout the team. Even in a manager’s office (there are only two of these), the glass doors are seldom shut except for conference calls. One door has a sign: “If you have a good idea, no need to knock.”

Prior to the recent CFI 2.0 transformation, our designers sat in a design team with a design team lead nearby, and our project managers sat with their lead—the floor was organized by discipline. Now, there is little in the way of physical separation or hierarchy—no walls or other barriers to separate those teams. Everybody’s desk is set up the same way; a team lead is just one of the team. In many organizations, trust is built by formality and hierarchy. Ours is just the opposite—we maximize interaction, and we trust everyone to perform without the traditional mechanisms of physical hierarchy.

Managing the Portfolio

People often ask us: How do you evaluate the “return potential” of a specific innovation project? As we’ve shared, we currently organize around Big Idea platforms—Mayo Practice, Connected Care, Health and Well-Being, and the Innovation Accelerator. Each platform has a portfolio of projects that meet a range of criteria in terms of their complexity, value and financial impact (for example, new revenue or expense reduction), or societal impact (for example, access for an underserved population). We think a lot about innovation with impact and innovation that addresses Mayo Clinic’s most significant challenges in areas such as access, value, efficiency, service, affordability, and integration. In the beginning, we needed to demonstrate significant financial return on innovation so we selected projects with more of a bottom-line impact. In contrast, we now have a more balanced portfolio approach so we now continue to consider financial return but also societal impact.

We also tend to favor projects that have leverage into other projects; for example, many of the prototypes for electronic care delivery or for redesigned care teams have a reach into other platforms. Those projects tend to create a lot of value and give support to the total “here, there, and everywhere” vision. We know it can be limiting to think of the platforms as individual silos; so today when we prioritize projects, we look at the entire vision, not just an individual project and its return on innovation in a single platform.

We should also add that the Center for Innovation is funded from three sources—Mayo Clinic operations, philanthropy, and revenue and/or equity from new products and services. The CFI has been in a building mode over the past five years, and it required a more significant investment in the early years. Now that we are established, the CFI is committed to generating a return that many times over exceeds its operational expenses.

Gaining Strength Through Collaboration

Many innovation organizations approach their existence as an organizational silo, unable or unwilling to interact with the outside or even with potential stakeholders, contributors, or test beds within their own enterprise. Not so with CFI.

Not just to survive but also to build bonds, leverage resources, and flourish, CFI continuously connects internally, with committees, departments, divisions, and business units, and externally, with companies, universities, and academic centers. Internally, our value to other departments lies in what we can bring: our processes and methodology in how we approach our work, the design studio staffed with innovation experts and design researchers, the Outpatient Lab to prototype and test our projects, and the discipline of design thinking. Externally, we have established relationships with world-class leaders in their fields—Delos, MIT, Cisco, Destination Imagination, Verizon, Intel, Aetna, Mercy Health System, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, Arizona State University, GE, IDEO, IBM, University of Minnesota, Doblin, Best Buy, 3M, Yale University … the list goes on. We are inviting more people into the conversations around transforming health delivery. Although it requires time and a deep commitment to manage these collaborations, our approach enriches both the process and the result.

Changing the World

From the beginning, we’ve sought to “change the world” of health care, both within and outside Mayo Clinic. That will never happen if we keep our innovations to ourselves or if we simply install them as changes into the practices we work with to develop prototypes and prove the concepts.

As a consequence, all through the evolution of CFI, we have emphasized and invested in communication. Really, as Chapters 5 and 6 describe, it goes further than traditional communication into a broader, deeper transfusion of intellectual content around the health care experience—from innovation methods to the latest industry conversations heard, to the TRANSFORM symposiums we lead, to the projects that are initiated in the practices but gain traction through CoDE.

This transfusion not only improves our competence and credibility but also maximizes the impact of each innovation. People not only learn about the vision but also see how it works and see how it fits together. The transfusion builds our capabilities and our successes and furthers Mayo Clinic as a whole as a health care leader.

The value of the transfusion, and the importance given to it by us as transformative leaders, is hard to overstate.

Approaching CFI 2.0

As a natural consequence of rapid growth and a need to organize and channel this growth, as stated above, we initially adopted a more typical siloed approach and structure to managing the individuals on the teams. While we managed our projects around our vision, our people were still managed in silos built around expertise and activity—design teams were led by a design manager, project management teams were led by a project management lead, and then there were a few embedded skills and resources like IT and communications that reported to functional managers wholly outside of CFI.

Because of the flat and informal organizational structure, and with the physical interaction and comingling described above, it worked pretty well. Design, project management, and other teams within CFI reported to a single layer of CFI leadership—our administrative director, our medical director, and our associate medical director—a.k.a. your coauthors. The frictions and inertia of hierarchy didn’t run too deep—things got communicated; things got done.

But we remained concerned about the siloed, functional approach. When executing on a holistic vision of providing health and health care “here, there, and everywhere,” could one really manage separate silos and groups addressing this singular, grand vision? Would team members building electronic interfaces for Health and Well-Being consider, or leverage from, similar interfaces being developed for Connected Care?

The answer, knowing our informality, the absence of physical barriers, and an innovation “space” conducive to interaction on the floor, and at the watercooler, was probably yes. Team members and team leads would talk to each other; they would share, out of a natural curiosity to keep up with what was going on and consistent with the general camaraderie and gestalt of the greater CFI team.

But we felt, especially going forward, that there would be challenges. The team was growing. More team members (60), more projects (100), more constituents, more technologies, more of everything. We were experiencing a gradual evolution from managing a small, entrepreneurial startup to a large enterprise-scale team. We felt a greater complexity and interplay between our platforms and projects. The scope and impact of our projects were expanding as well; there was a greater quest for a major transformation, a societal impact, extending well beyond improving individual patient experiences.

As a consequence, we saw an opportunity to take our organization another step forward, to take the process of management of CFI from “good” to “better.” We wanted to gain from the exchange of ideas from highly networked, collaborative, and sharing teams that did not have individual objectives or agendas. We wanted everyone to march forward together in equal step toward our vision, without large amounts of management direction and redirection. We wanted everyone to lead themselves toward the goal. We also wanted to balance the natural tension that occurs between structure and autonomy.

We wanted to emulate the models of many high-tech companies, where innovation teams can see the customer, get the vision, and execute on it with a minimum of direction and a maximal view of the “end in mind.” We wanted our teams to be able to “touch it and play with it” and see how the customers and the marketplace react; that in itself would provide plenty of motivation.

Our hunch was that we needed to keep the flat organization, and we needed to make the teams as “self-leading” as possible. We knew we were at a good starting point, with talented physicians, designers, and project managers with a wide range of experience and an intense interest in the end vision. We just weren’t sure we had the organization or process of management in place to “get there” the best way.

You might say we were looking to transition from a “process of management” to a “process of leadership.” A process of management implies more structure, rules, and day-to-day handholding of subordinates and subordinate processes. A process of leadership implies more self-direction, more self-motivation and resourcefulness. Peter Sander, in his book What Would Steve Jobs Do? (McGraw-Hill, 2011), defines leadership as “getting people to want to—and to be able to—do something important.” It’s that sense of self-actualization and self-reliance, toward something important, that we wanted to make central to CFI.

So we had our own jam session. We met as managers, team members, and constituents, and best of all, we brought in some of the experts from the External Advisory Council to give us their take on how to move forward into CFI 2.0—our leadership model of the future.

Change by Design: A Jam Session with our External Advisory Council

You may recall from Chapter 3 our discussion of the External Advisory Council (EAC), our group of external “innovation whisperers” from whom we’ve received valuable insight from the beginning. Normally we meet with the nine-member EAC twice a year.

We developed a list of four questions for the EAC members to try to get to CFI 2.0—our leadership model of the future:

1. What are ways to minimize silo thinking and silo behaviors?

2. What is the optimal size of a team?

3. How much leadership structure should be in place at the platform and/or core level?

4. What other advice do you have for us to work more effectively?

We presented this list and received a fabulous set of observations and prescriptions.

Their observations were so insightful that we decided to share them in summary form as useful advice for your own innovation enterprise. Most of these observations center on change, organization, communication, collaboration, and leadership.

CFI 2.0: It Takes a Village

Not surprisingly, it took some time for the collective wisdom just presented to sink in and turn into actions on our part. You’ll note, for instance, that not every idea or thought was in agreement, like meeting formats—we had to work through those ideas too.

We leaned in to our team to build CFI 2.0. We had an off-campus retreat at an arts center to exchange thoughts and ideas and begin to formulate a roadmap, articulating how our work integrates to one coherent vision, how we organize, how we plan and sequence our work, and how we allocate resources. We started by identifying a set of principles characterizing what we value as individuals and teammates to carry us forward with CFI 2.0:

1. Mutual respect

2. Trust, honesty

3. Open, authentic conversations

4. Accountability

5. Personal and professional growth; continuous learning

6. Seeing everyone as creative, helping each other build creative confidence

7. Generating results—for the CFI, for Mayo Clinic, and most important, for our patients

We partnered with our human resources colleagues and incorporated such leading-edge organizational trends and practices as highlighted in HR magazine, “Try Leading Collectively” (January 2013):

![]() There is a transformation under way toward more complex, interconnected, and dynamic structures.

There is a transformation under way toward more complex, interconnected, and dynamic structures.

![]() There is a trend toward shared responsibility and mutual accountability toward a strategic direction.

There is a trend toward shared responsibility and mutual accountability toward a strategic direction.

![]() There is greater use of “collective leadership” and mutual accountability-based approaches and structures.

There is greater use of “collective leadership” and mutual accountability-based approaches and structures.

What came through the process, loud and clear, was the idea of reorganizing by platform—and making each platform a dynamic “interdisciplinary village” reminiscent of smaller, early-phase startups where everybody tends to do everything—“All for one, one for all” might be the motto. We also fully embraced the idea of rotating CFI members across platforms—to gain the experiences and to expand the breadth and depth of each platform as they touched it.

We also reviewed our methodology to determine how to accelerate the pace, with a bias toward agility, speed, clarity, and implementation.

As a result, today we are organized by four platforms: Mayo Practice, Connected Care, Health and Well-Being, and the supportive Innovation Accelerator. Each platform is an interdisciplinary “village” with a manager and an interdisciplinary team of designers, project managers, innovation coordinators, IT professionals, and others.

In the end, our Mayo Clinic human resources team supported a precedent-setting new structure, moving from a functional orientation to a team-based model with platform managers supervising very diverse employees. The teams sit in comingled fashion with adjacent desks; designers sit next to coordinators, project managers, and embedded IT folks. There are no physical or organizational barriers between members of a platform team, and with rotation, each team member contributes and becomes an expert on the adjacent platforms.

Evolving Our Portfolio Structure

In Chapter 3, we introduced the hierarchy of platform, program, and project—which we clarified and defined in the new CFI 2.0. Each platform (transformative) has a small number of programs (strategic), and within the program, a smaller subset of projects (tactical). Here, once again, is our definition of the levels in the hierarchy—really, the portfolio of activity within CFI:

![]() Platform. A collection of programs grouped together to facilitate effective management of that work to meet strategic business objectives

Platform. A collection of programs grouped together to facilitate effective management of that work to meet strategic business objectives

![]() Program. A group of related projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually

Program. A group of related projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually

![]() Project. A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result

Project. A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result

Appendix B lists and illustrates our current portfolio of CFI projects and the platforms they fall under.

Making Other Communication and Leadership Changes

The new CFI 2.0 includes other changes:

![]() Weekly team meetings are now held and dedicated to sharing our work across platforms.

Weekly team meetings are now held and dedicated to sharing our work across platforms.

![]() For each platform, a physician lead has been named to partner with the platform manager.

For each platform, a physician lead has been named to partner with the platform manager.

![]() The former design lead in the previously structured “design” group has been recast as a design strategist, advising user research across the platforms and serving as a mentor for the designers.

The former design lead in the previously structured “design” group has been recast as a design strategist, advising user research across the platforms and serving as a mentor for the designers.

![]() Designer and project manager career ladders with three levels have been crafted and implemented.

Designer and project manager career ladders with three levels have been crafted and implemented.

With this new structure, we feel we are gaining the rich interchange of ideas and the self-directed and self-motivated qualities of many leading innovation organizations. We have transitioned from a team that needs to be managed to a team that leads itself—an important transition in any organization. We have evolved from being managers to being enablers and communicators of the greater vision and design and all the components thereof.

Innovation the Mayo Clinic Way: Evolving the Leadership Model

In this chapter, we’ve talked about leadership and how we’re innovating innovation to get to CFI 2.0:

![]() The most effective innovation organizations will evolve from a management model to a leadership model—a model where the customer and the vision provide the basis for self-leadership, and day-to-day management direction and review are less necessary.

The most effective innovation organizations will evolve from a management model to a leadership model—a model where the customer and the vision provide the basis for self-leadership, and day-to-day management direction and review are less necessary.

![]() The leadership model is more likely to be based on interdisciplinary villages built around platforms than to be based on a traditional structure isolating disciplines into separate silos.

The leadership model is more likely to be based on interdisciplinary villages built around platforms than to be based on a traditional structure isolating disciplines into separate silos.

![]() Interdisciplinary villages combine skills and disciplines into a team, avoiding physical and organizational barriers. All members work toward a common vision.

Interdisciplinary villages combine skills and disciplines into a team, avoiding physical and organizational barriers. All members work toward a common vision.

![]() Rotation between villages expands contributions and strengthens the linkages between the platforms, while also expanding the skill sets and experiences of team members.

Rotation between villages expands contributions and strengthens the linkages between the platforms, while also expanding the skill sets and experiences of team members.

In Chapter 8, we offer examples of how leadership and other principles we’ve covered are put into play in our three delivery platforms: Mayo Practice, Connected Care, and Health and Well-Being (the fourth platform, the Innovation Accelerator, was discussed in Chapter 6).