CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FOUR

Fusing Design Thinking with Scientific Rigor

The Fusion Innovation Model

If I asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have told me “A faster horse.”

The Ford “faster horse” quote is an old standard in the annals of innovation, and it is by no means new to any of you familiar with innovation literature. We bring it to you not so much as a revelation but as a way to frame our thoughts and to introduce the how component of our innovation story—the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation approach and model for making innovation happen.

Of course, the main idea embedded in the quote is that, if we think in narrow terms, we’re unlikely to succeed in identifying what the customer really needs. As a result, our innovation will be off track from the beginning; any innovation that ignores true, deep, or “latent” customer needs will usually fail—becoming downgraded to a shiny new idea or gimmick or gadget or product that fails to create customer value.

We know that even if we ask the patient- customer what he or she needs, we’re still exposed to the risk that we’ll miss badly with our innovations. Why? Because in many cases, customers can’t tell us what they really need. Put differently, they tend to frame their answers in what already exists or is known to be available—in the oft used quote, a faster horse.

At CFI, we look beyond these immediate and obvious needs. We must, because the process of health care delivery is too complex and it has too many moving parts and technical complexities for most customers to really be able to articulate what they need, particularly within a framework of what is possible. Furthermore, most customers have lived with our current health care delivery standards for a long time; as a result, their expectations have been lowered, and their vision of what’s possible has been limited. It therefore falls to us to envision and reach a level of health care delivery well beyond what our patient-customers expect.

Health care brings with it additional complexity. Retaining a singular, unwavering focus on patient- customer needs is critically important but also not enough: it will not get the job of reinventing health care delivery done. Why? In part because we work in a large organization of physicians and health care providers in a demanding field that defaults to tradition and considers unacceptable anything that puts the delivery of its product at risk. Beyond that, we also work at the behest of a network of payers, secondary providers, government agencies, and others, all of whom have a stake in what we do.

Furthermore, change is good—but only if we’ve demonstrated that we know what we’re doing and that we’ve considered the alternatives. Patients’ lives are at stake, after all. Satisfying or even delighting in the short term doesn’t count if we’re compromising long-term health outcomes. Furthermore, as we’ve mentioned, the world is training its collective green eyeshades on the cost of health care. Bottom line: we must satisfy our customers—all of them.

So in this complex context, early on, we had to define how we innovate. How do we deliver an exceptional customer experience, while still satisfying risk-averse internal constituencies that demand scientific rigor to move forward? How do we keep every project we bring to the table from succumbing to the “organizational antibodies” that tear it apart and reject it, never to see the light of day?

From the Beginning

We pondered this carefully right from the start. We needed a method and process flexible and open-minded enough to get to transformative innovation, yet structured enough to meet the demands of a traditional medical practice and beyond to a vast and well-entrenched global field of medicine.

We started our SPARC Lab, engaged with consultants, and visited leading innovators like IBM, 3M, Procter & Gamble, and Cargill who were in similarly complex industries to learn and observe what was the same and what was different about their situations. We synthesized from these visits and our own early experiences. It all led to this: to get to true customer-driven transformative innovation, we needed a process that was simultaneously rigorous about understanding customer needs while being flexible in how those solutions would be delivered. And those solutions had to clear the bar of scientific rigor and testing before bringing them to market. We couldn’t tie ourselves down with unnecessary inertia and bureaucracy.

We needed a process that could Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast.

The truth is that, really, rather than a strictly defined process, we sought a model for innovation. The model would be deeply customer driven and highly creative, yet scientific and structured enough to provide rigor and cover the organizational bases. Make it too loose, and nobody would buy in; we would create cool ideas that would never make it to market. Make it too tight, and little would happen, or at best, we would be tied down to incremental, process-driven innovation confined to tweaking the known.

From all of this we arrived at something we call the Fusion Innovation Model. The Fusion Innovation Model “fuses” the important methods of design thinking, scientific method, and project management into a thought process under which we all operate. It also suggests a process flow to execute a program, but it doesn’t specify it. We think, live, and breathe by the spirit of the fusion innovation method, not by the “letter” of a defined process. The resulting balance and flexibility are more organic, giving our designers, project managers, and physicians the freedom to discover, design, and deliver transformative innovation while avoiding the tentacles of bureaucracy.

The Fusion Innovation Model allows us to Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast.

This chapter is devoted to presenting and illustrating the key principles that underlie the Fusion Innovation Model—design thinking, scientific method, and project management. We will also take a short tour of the generalized flow we use to move a project forward. In Chapters 5 and 6, we’ll add on the “transfusion” components—how we nourish fusion innovation and keep its activities connected and relevant to the organization. Finally, in Chapter 7 we’ll describe how we’ve evolved our leadership model to manage our innovation in practice.

Forming the Fusion Innovation Model

From an organization like Mayo Clinic, most of you would likely expect a deeply detailed, structured innovation process that bases everything on data and mandates numerous meetings and lengthy structured project reports. Most of you in large organizations probably experience this type of process.

The reasons would be clear. Innovators must be held accountable for what they do. Everybody wants tested, proven ideas, ideas that have passed muster with all stakeholders, no surprises. Everyone wants a good return on their investments, a healthy ROI, especially when there’s a lot of investment at stake. Nobody wants a rogue team to deliver a biased or unmarketable innovation or to make a costly mistake. In short, innovation brings tension to an organization.

Beyond general tensions around investment and change, innovation also calls out many more issues to balance in any innovation method or model an organization deploys:

![]() Intuition versus science. Intuition, without proof, can be wrong; science without intuition can miss opportunities and take too long.

Intuition versus science. Intuition, without proof, can be wrong; science without intuition can miss opportunities and take too long.

![]() Speed versus precision. Speed without enough precision leads to unacceptable errors, putting lives at risk; precision without speed misses opportunities. The wrong thing done right is still the wrong thing.

Speed versus precision. Speed without enough precision leads to unacceptable errors, putting lives at risk; precision without speed misses opportunities. The wrong thing done right is still the wrong thing.

![]() Structure versus freedom. Structure brings certainty to the methods; freedom allows open thinking encircling more opportunities, and it reduces inertia.

Structure versus freedom. Structure brings certainty to the methods; freedom allows open thinking encircling more opportunities, and it reduces inertia.

![]() Customer-driven versus process-driven innovation. Customer-driven innovation more likely transforms the marketplace; process-driven innovation may miss transformative nuggets. In many organizations, the process becomes the customer. Innovation serving a process and not a customer is far less likely to succeed, and it is more likely to consume resources.

Customer-driven versus process-driven innovation. Customer-driven innovation more likely transforms the marketplace; process-driven innovation may miss transformative nuggets. In many organizations, the process becomes the customer. Innovation serving a process and not a customer is far less likely to succeed, and it is more likely to consume resources.

![]() Known versus unknown. We sought a model that would take us into the unknown—really, that would turn as much “unknown” into “known” as possible but that would not get stuck on what we already knew.

Known versus unknown. We sought a model that would take us into the unknown—really, that would turn as much “unknown” into “known” as possible but that would not get stuck on what we already knew.

![]() Risk versus certainty. Certainty is nice, but it takes too long, and it can be constraining. Obviously we can’t accept too much risk when lives are at stake, but when they are not, we’re willing to tolerate a lot of risk to move forward.

Risk versus certainty. Certainty is nice, but it takes too long, and it can be constraining. Obviously we can’t accept too much risk when lives are at stake, but when they are not, we’re willing to tolerate a lot of risk to move forward.

![]() Creativity versus business constraints. Simply, good ideas may be too expensive to deliver. But if we always let business constraints squelch good ideas, our efforts in the end will suffer. There are times when a lack of an obvious business model should not stop a radical innovation. The trick is to know when and how many of those times your organization can live with.

Creativity versus business constraints. Simply, good ideas may be too expensive to deliver. But if we always let business constraints squelch good ideas, our efforts in the end will suffer. There are times when a lack of an obvious business model should not stop a radical innovation. The trick is to know when and how many of those times your organization can live with.

![]() Creativity versus efficiency. A relentless emphasis on efficiency can make an enterprise less creative; such an enterprise settles for routines, not progress or action. We can become very efficient at doing the wrong thing.

Creativity versus efficiency. A relentless emphasis on efficiency can make an enterprise less creative; such an enterprise settles for routines, not progress or action. We can become very efficient at doing the wrong thing.

![]() Discrete versus continuous. Process-focused organizations tend to view most activities, including innovation, as a series of discrete, sequenced steps. Start a task, do the task, finish a task, review it, and start the next, always in order, always in the same order. Emphasis is placed on the “start” and “end” of the task versus what is happening during the task. In contrast, the “continuous” approach has reviews and checkpoints, but it may do several things simultaneously—or it may return to an earlier stage (as below) to discover and develop something new.

Discrete versus continuous. Process-focused organizations tend to view most activities, including innovation, as a series of discrete, sequenced steps. Start a task, do the task, finish a task, review it, and start the next, always in order, always in the same order. Emphasis is placed on the “start” and “end” of the task versus what is happening during the task. In contrast, the “continuous” approach has reviews and checkpoints, but it may do several things simultaneously—or it may return to an earlier stage (as below) to discover and develop something new.

![]() Iterative versus linear. Similar to the above: a flexible process allows the physicians, designers, and project managers to explore or experiment with something found from an earlier discovery. An innovation may proceed through the same “steps” several times. Sequence is less important than true discovery; innovators have more freedom to “go where the project takes them.”

Iterative versus linear. Similar to the above: a flexible process allows the physicians, designers, and project managers to explore or experiment with something found from an earlier discovery. An innovation may proceed through the same “steps” several times. Sequence is less important than true discovery; innovators have more freedom to “go where the project takes them.”

These tensions may seem obvious. Yet in our observations of innovation in complex organizations, the tendency is to become more structured and process driven over time even if it does not start that way. In some cases, the customer is barely noted on the list of objectives. We saw this in several companies we visited where they have fallen into the trap of measuring success almost exclusively in terms of the number of patents generated. To be fair, patents are essential for many organizations, but, without doubt, some of those patents edged toward serving a process rather than actually being delivered to market. In large organizations, a planned and repeated reevaluation of the model is required to correct the drift toward process over creativity.

At Mayo, in developing our innovation model, we strived to become anything but a patent mill, anything but an organization in which “the innovation served the process” rather than the process serving the innovation. In forming this idea, our early discussion with 3M was particularly enlightening. We visited 3M’s headquarters in St. Paul to learn how to position innovation within a complex enterprise. 3M had just undergone a transition from CEO James McNerney (originally from GE) to George Buckley. McNerney had merged innovation with quality improvement, and he had placed a “relentless emphasis on efficiency.” Buckley saw it differently, and he sought to restore the culture toward growth, especially important in today’s “idea-based, design-obsessed economy.” The 3M team noted that process and quality improvement “demands precision, consistency, and repetition,” while innovation needs “variation, failure, and serendipity.”

As a consequence of these discussions and observations, we began to resolve the “tensions” list in favor of a more human-centered, flexible model that entertained deep customer understanding and creative solutions while also adhering to the principles of science—all while preserving enough structure to be manageable. We felt strongly that too much structure and process would be more of a burden than a blessing and would diminish our results. And, since quality management was already tasked to another group in Mayo Clinic, we were free to pursue true customer-focused innovation.

It all led us to the Fusion Innovation Model.

What Is the Fusion Innovation Model?

The Fusion Innovation Model is, really, a mindset and a thought process.

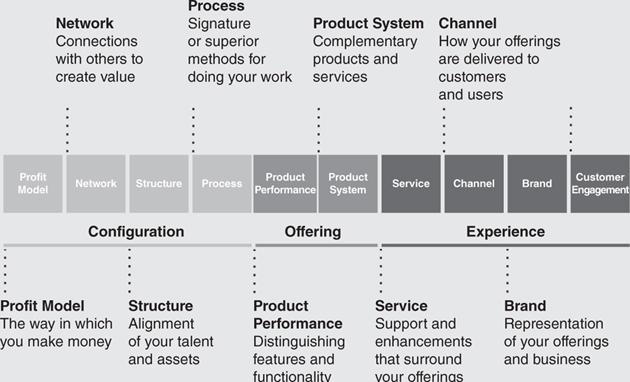

As a thought process, it blends the disciplines of design thinking, scientific method, and project management together as a whole. As illustrated in Figure 3.12 at the end of the last chapter, the three guiding principles are “fused” to operate together rather than separately.

Really, it’s a Zen-like absorption in the “truths” of the fused disciplines, a deep commitment to a single guiding light, as a single principle. It is not a doctrine or a manifesto or a checklist where we follow one discipline at a time, design thinking on Mondays and Tuesdays, scientific method on Wednesdays and Thursdays, project management on Fridays. We do all three all the time. It may seem idealistic, but it is not. We benchmark ourselves against this principle every day; it helps us achieve balance and move more efficiently through our innovations.

The Fusion Innovation Model fuses three distinct disciplines:

1. Design thinking. Blends a deep customer empathy and understanding with creative design and business constraints into attainable and marketable insights

2. Scientific method. Strives to turn controllable experiments and measurable evidence into unbiased and proven solutions

3. Project management. Moves a project forward in a manageable and demonstrable way, with a timeline and a set of structural guideposts and stages to ensure that it is accomplishing what is intended

These disciplines will be explained and illustrated by example throughout this chapter.

The Fusion Innovation Model is guided by the customer, not the process. The process fuses naturally to achieve customer objectives and organizational objectives alike. When you’re doing right by the customer, especially the “greater” set of customers inside and outside your organization, you’re more likely to get it right.

At the end of the day, the Fusion Innovation Model achieves what we think is the right balance of customer and customer experience, and process and process rigor. This organic balance helps us to overcome organizational barriers and antibodies that slow projects down and to bring more discovery and innovation to light more quickly. Ultimately, we believe it is the best way to transform the greater Mayo organization and the delivery of the 21st century model of care, and it is also the best way to introduce innovation into any complex environment.

We believe that the Fusion Innovation Model:

![]() Achieves a greater synthesis. The Fusion Innovation Model fuses our own experience and culture with what we observed outside Mayo at 3M, Procter & Gamble, IBM, and other complex organizations and what we heard from the experts at Doblin and IDEO and other innovation thought leaders.

Achieves a greater synthesis. The Fusion Innovation Model fuses our own experience and culture with what we observed outside Mayo at 3M, Procter & Gamble, IBM, and other complex organizations and what we heard from the experts at Doblin and IDEO and other innovation thought leaders.

![]() Is simpler. It is not a rigid “process” but rather, a flexible mindset.

Is simpler. It is not a rigid “process” but rather, a flexible mindset.

![]() Brings in technology the right way. Technology is embraced, but it serves the innovation and strategy rather than being the end in itself.

Brings in technology the right way. Technology is embraced, but it serves the innovation and strategy rather than being the end in itself.

![]() Resolves conflicts. The fused model is about balance from the beginning—neither “design” nor “science” nor “management” takes over. The true focus is on the customers, not the process.

Resolves conflicts. The fused model is about balance from the beginning—neither “design” nor “science” nor “management” takes over. The true focus is on the customers, not the process.

![]() Serves many masters. Patient experience “wins,” but so do the most scientific-minded and skeptical of our constituents—not just the patients but also the providers and payers.

Serves many masters. Patient experience “wins,” but so do the most scientific-minded and skeptical of our constituents—not just the patients but also the providers and payers.

![]() Allows degrees of freedom. Project teams can imagine, create, and experiment without following an exact formula. The process serves innovation; innovation doesn’t serve the process.

Allows degrees of freedom. Project teams can imagine, create, and experiment without following an exact formula. The process serves innovation; innovation doesn’t serve the process.

![]() Is flexible to the nature of the project. One rigid process doesn’t apply to all. Instead, there are many kinds and sizes of projects for many constituents. It’s a guided framework for thought—not a rigorous checklist—and that makes it easier for our people (who are all different as well!) to work within it.

Is flexible to the nature of the project. One rigid process doesn’t apply to all. Instead, there are many kinds and sizes of projects for many constituents. It’s a guided framework for thought—not a rigorous checklist—and that makes it easier for our people (who are all different as well!) to work within it.

![]() Avoids faster horses, organizational antibodies, and inertia. This is the best feature of all: the Fusion Innovation Model is true to the customer and gets the most out of what we have to offer. It is fun, engaging, and creatively challenging for our people. It’s also more interesting to manage.

Avoids faster horses, organizational antibodies, and inertia. This is the best feature of all: the Fusion Innovation Model is true to the customer and gets the most out of what we have to offer. It is fun, engaging, and creatively challenging for our people. It’s also more interesting to manage.

![]() Places trust in our teams and personnel. Rather than strict adherence to code or protocol, we allow our teams the flexibility to approach a project as they see fit. We trust our teams to be thorough and smart about how they assess the customer experience before, during, and after an innovation, how they use experimentation and data to validate it, and how they identify progress and demonstrate results.

Places trust in our teams and personnel. Rather than strict adherence to code or protocol, we allow our teams the flexibility to approach a project as they see fit. We trust our teams to be thorough and smart about how they assess the customer experience before, during, and after an innovation, how they use experimentation and data to validate it, and how they identify progress and demonstrate results.

From here, we will proceed to describe the three fused disciplines of the Mayo Clinic Fusion Innovation Model—design thinking, scientific method, and project management. The discussion will be slightly weighted toward design thinking because it is perhaps the least tangible component of our model. Scientific method and project management are no less important, but they tend to be more understood and they are already deployed by most organizations.

What Is Design Thinking?

Part I of this book brings our story forward from the early days of innovation at Mayo to the early days of the Center for Innovation and our initiative to bring about a new, better, experience-driven model of care. As we began our journey, we knew we had to develop an operating philosophy—an approach—to seeing the world and defining transformational innovation within it.

Early on we engaged with IDEO, whose slogan “We create impact through design” resonated with us. We met with founder David Kelley and with Tim Brown, who is now the president and CEO and is also the author of Change by Design, an excellent read on the design thinking topic. Brown is also a member of our CFI External Advisory Council.

IDEO has evolved the concept of design from being a mostly tactical, analytical process for putting something together, making it work, and making it look good according to some predefined specification or set of requirements to being something that embraces a more strategic sense of understanding human and organizational needs and behaviors. For IDEO, these concepts all converge into something called design thinking.

The design thinking approach, in IDEO’s words, “brings together what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable.” A designer designs a product that works. A design thinker starts with gaining an understanding of customer needs, recognizing patterns, and developing a strong intuition about those needs. A designer then applies design tools and a healthy dose of testing and verification to validate the initial design concepts. Importantly, you don’t have to be a designer to understand and apply design thinking. It is a discipline with a body of knowledge that can be taught and learned.

As we see it, design is tactical, and design thinking adds strategic elements that turn inventions into innovations. Those elements turn innovations into transformative innovations. For us, design thinking starts with the customers, and it incorporates not only an understanding of the customers but also a deep empathy with them. It adds what we call contextual creativity—that is, creativity applied with that true understanding of the customers and that functions within the boundaries of technology, business, and organizational needs.

The crowdsourced Wikipedia definition of design thinking works for us:

Design thinking is the ability to combine empathy for the context of a problem, creativity in the generation of insights and solutions, and rationality to analyze and fit solutions to the context.

At the risk of belaboring the concept, the Fusion Innovation Model does not stop at design thinking. Rather, it integrates design thinking with scientific method and project management to provide the discipline to move things forward in a demonstrably correct manner. Design thinking is the secret sauce that makes innovation really matter, by understanding and serving customer and business needs, exploring the possibilities, and making the unknown known. The scientific method rigorously tests concepts, and project management moves the known forward and makes it possible.

Time Out for Examples

As a means to illustrate, we’ll take a small detour to describe a few actual examples of what we do. We’ll use these examples to frame our discussion of the principles of the Fusion Innovation Model.

First is our Asthma Connected Care App, a project in the implementation phase, already a winner of an Edison award for innovation. The issue was how to help teenagers with asthma manage their condition more effectively and have direct contact with their medical teams. The second is the Smart Mirror, a project in a working prototype stage. Both are part of the Connected Care platform, and both also have significant hooks into the Health and Well-Being platform, as they are really designed to augment health and well-being on an ongoing basis, before and after health care events. The third project is our Jack and Jill Rooms, and it is part of our Mayo Practice Redesign platform. As one of our earlier successes, Jack and Jill Rooms redesigned the traditional patient exam room to improve patient interactions with physicians and staff members and to incorporate family members and others more comfortably into the process.

Staying Tethered: The Asthma Connected Care App

The Asthma Connected Care App (Figure 4.1) moved through the design and testing stages during 2011 and early 2012. The “small frame” goal was to create a way for adolescent—aged 13 to 19—patients with chronic and “persistent” asthma—requiring treatments two or more times a week—to keep up with their health regimen. By staying connected to care providers, care and well-being would improve, and they would avoid a sudden worsening of their condition and a likely trip to the hospital or emergency room.

FIGURE 4.1. ASTHMA CONNECTED CARE APP

The “big-picture” goal was to demonstrate the effectiveness of continuous, connected care for a broader assortment of chronic diseases by managing care locally with a connected app, tethering the patients to their care teams “asynchronously” through data exchanges and text messages and “synchronously” (in real time) as necessary. We felt that with the Connected Care app, adolescents would feel empowered, providers would have much more data with which to make decisions, and previously unseen trends would emerge. In the end, our intuitions were confirmed, and we learned a lot about effective remote disease management, including how to connect to those patients.

The Asthma Connected Care App shows how we are transforming care delivery, moving the center of gravity away from the traditional, physician-based exam room to the daily life and flow of the patients, in their home, place of employment, school, and community.

Seeing Yourself as Others See You: The Smart Mirror

The Smart Mirror is a prototype mirror designed for seniors (Figure 4.2). The Smart Mirror is used like a bathroom mirror, and it is connected to a small mat that the patient-user stands upon while looking in the mirror, as would happen during a routine morning “get ready for the day” sequence. The mirror has an electronic display, and it is tethered not only to the floor mat but also to the cell phone network for outbound communications. The mirror displays reminders to the user to take scheduled medications, and it collects data when the user acknowledges taking those medications. The mat collects data on the patient’s weight.

FIGURE 4.2. SMART MIRROR

The information is passed on to a caregiver in the responsible health organization. It is also set up to be passed on to chosen outsiders, such as the user’s loved ones as a check on the patient’s activity and appearance. Caregivers can check on weight as an evidence of diet or congestive heart failure problems and on the proper dosages of medicine. Like the Asthma App, this concept has many more possible applications not only in elder care but also in the broader patient space, as well as for chronic conditions beyond aging, skin disorders as an example. With a broader set of data collection tools, including nanotechnology and embedded patient sensors, the possibilities are endless. Also like the Asthma App, the emphasis is on health and well-being, not traditional health care events. The working prototype is under development in the CFI Healthy Aging and Independent Living (HAIL) Lab.

Both models incorporate enabling technology to make a more desirable model feasible for the customer. Additionally—and importantly—viable business models are emerging as health care finally catches up with other industries in offering technology-enabled delivery well integrated into process flows.

Rethinking the Outpatient Exam Space: Jack and Jill Rooms

The Asthma App and, to a degree, the Smart Mirror are designed to reduce dependence on clinical visits. But when visits do occur, we naturally seek excellence in that experience too. So we created a project to examine patient-doctor interactions—to make the exam and discussion of results process more comfortable and productive not only for the patient but also for the physicians and staff members, as well as any of the patient’s family members who might be present. The project was conceived in recognition of the fact that outside of cosmetic changes in furniture and décor, outpatient exam rooms really haven’t changed much since 1900. As we’ll see, the name of the project arose from our findings; it wasn’t even on the radar in the beginning.

A team of CFI designers studied patient-physician interactions and the involvement of families, and they quickly found a number of problems. Computers were set up so that the physicians could view them easily, but not the patients. There was little room for family members, and the space was dominated by the exam table, dressing area, sinks, and exam tools—even though most appointments following the initial evaluation tended toward conversations about the patient’s history and symptoms. In fact, our research showed that 80 percent of the time used in an office visit was for conversation versus only 20 percent for examination.

Observation and experimentation led to a series of full-scale prototype exam rooms, first conceived and constructed using foamcore, cardboard, and similar materials in the CFI lab, then put into practice as a prototype. The setup that resonated most with the group was the creation of separate consultation and examination rooms connected by a doorway. The consultation room was outfitted with a round table, four chairs, and a computer monitor on a swivel. Real patient interactions were observed in the new configuration, and researchers noted that patients were more comfortable and relaxed, they asked more questions, and they were more interactive in creating their home health care plan.

But there was one more issue: what about the additional floor space these dual rooms would require? An innovation such as this must fit within business constraints to succeed. The design team came up with a solution that shared a central exam room with two consultation rooms—in the manner of the central “Jack and Jill” shared bathroom from the 1970s TV show The Brady Bunch. Solid soundproof doors, lighting changes in the rooms, and a system to signal occupancy rounded out the new design. The design not only resonated with patients and their families but also with physicians, who could use one room to type up notes while the patient changed in another. Staff could clean and set up the exam room for another patient while a consultation was occurring in the neighboring room. The improved patient flow more than made up for the extra space required. The Jack and Jill exam room was shown in Figure 3.3 in Chapter 3.

These descriptions are meant to introduce, not fully describe, these programs—obviously there is more to these stories.

Acquiring a Deep Understanding of Customers

In business, and in innovation, almost everyone talks about the customers.

These days, if you’re part of an innovation group or organization and you are not talking about the customers, you’re way outside the loop. You didn’t get the memo that good innovation doesn’t start with ideas, shiny technologies, or even existing products. It starts with the customers. To turn an idea or invention into an innovation, it must ultimately create value for customers and be accepted by them. Other ideas need not apply.

Many people talk about the customers, measure customer activity, collect customer inputs, pore over customer satisfaction survey results, and put customers into one of four neat market segments. But do they really understand the customers? Do they understand not only what the customers want and need but also what the pain points and dissatisfiers are? Do they understand the deep, innate wants and needs, the ones the customers can’t always or don’t always express or even think of? Do they look holistically at the experience?

Avoiding Faster Horses

To innovate, we must create more than a faster horse.

If we simply take customer inputs at face value, or if we evolve our products without considering the bigger picture of what customers want, we can find ourselves in the weeds pretty quickly. Consider the personal computer industry over the years. Did customers really just want faster processors and more storage and faster printers and better print quality—more “speeds and feeds,” as the industry put it? Perhaps there was a need. These features made computing work better—within its current experience.

But if you had focused just on speeds and feeds, you would have missed the boat. People really wanted to connect to each other and to enterprises—the Internet. As we found out even later, they really wanted the simpler tablet format to do this. So while the industry kept producing faster horses, it took too long to satisfy the greater customer need and desire. Nowadays the PC industry struggles to stay relevant.

Did real customers in the general public say they wanted the Internet? Did they say they wanted tablets? Hardly. These innovations emerged from an analysis of latent customer needs. They arose from intense observation, intuition, and some experimentation with the customer experience—from highly synthesized visions, a clear-eyed view of what was possible, and a willingness to try things.

Indeed, Henry Ford himself saw beyond the stated need to go faster, to find a faster horse. He observed that it was difficult to get more than one person on a horse. It was difficult to get protection from the elements. A horse required care around the clock. A horse could be difficult to control. Combine these insights with emerging technologies (and many more to come), and you arrive at the automobile.

But no customers at the time would have said that they wanted an automobile. They didn’t know it was possible. They couldn’t synthesize the need and available technologies into a big-picture vision. Innovators figured it out through observation, intuition, and a deep understanding of the customer experience.

Meeting Explicit Needs—and Going Beyond

It’s obvious that health care is complex, and most customers don’t know very much about it. To get customers—patients or people seeking information about staying well—to articulate what they really want in the health care space is a tall order, in no small measure because they don’t know what’s possible. Most can’t know.

Most people have had some experience with health care. They can describe a few pain points, like long waits in doctors’ offices reading outdated magazines. They can tell you—or show you—physical pain in the clinical setting, and we’ve done a lot in the medical community to mitigate that. But about the whole experience? About the greater health experience beyond the clinical visit? Probably not. Compounding this is the low expectation customers have of health care delivery, an expectation that is lower than they would have in other aspects of their lives. Therefore, their ability to tell us what they need is often limited. Yet that does not mean they do not want, need, or deserve much more. Many have simply accepted the status quo. It is up to us to find a way to understand these unstated needs.

Getting a true customer understanding starts with looking at the entire experience, then framing the large and small opportunities within it. It starts with gaining a deep understanding of what the customer really wants or needs, beyond what might be discovered through traditional means like focus groups, satisfaction surveys, or interviews—which are today’s primary methods in the health care space.

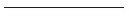

We must identify explicit, tacit, and latent needs.

The model in Figure 4.3 evolved from a 1950s’ analysis of knowledge and learning. That analysis held that some learnings are explicit and can be expressed in words, while others, like riding a bicycle, are tacit; that is, we know how to do these tasks, subconsciously, but we can’t put into words how to do them, and they’re hard to convey to someone else. We can only observe them.

FIGURE 4.3. A KNOWLEDGE HIERARCHY OF CUSTOMER NEEDS: EXPLICIT, TACIT, AND LATENT

We have flipped this model around and added a layer so as to take into consideration the reality of innovation in a complex environment, integrating the latent needs of both the customers and the providers. We feel that transformative innovation can be achieved only when these latent needs are met and exceeded.

First, we substitute needs for knowledge in the model. Some needs are explicit, and the customers can articulate them. Other needs grow out of their behaviors and experiences, but the customers cannot articulate them easily. These are tacit needs.

Customers can articulate explicit needs, like shorter waiting times or clear, easy-to-read treatment programs, simply if you ask them. The other, more subliminal, or tacit, needs are difficult to articulate. However, you can often determine the needs simply by watching customer behavior. The need for, and advent of, Microsoft Windows is a good example. Customers wouldn’t have articulated in a focus group or on a survey their need for multiple windows on a desktop. But the software designers would have seen the need clearly when they watched customers open one program, close it, open another, and repeat the cycle over and over.

To the explicit/tacit construct, we have added another layer: latent needs. Latent needs are so subliminal that not only can a customer or provider not articulate them but you’re also not likely to observe them in practice. You simply have to infer and synthesize them from layers of customer-supplied and observed data, with an overlay of deep thought, visioning, and experimentation in a context of what’s possible.

The Power of Latent Thinking

Automobiles, tablets, and many of the great transformational innovations of our times resulted from someone with a great vision, and the capacity for pattern recognition and synthesis, assembling customer inputs and observations with an understanding of the possibilities—to arrive at a strong and market-viable latent need. Recognizing the true big-picture latent need was the first step; the second was showing potential solutions together (or parts of them) to the customers to make them realize those solutions are what they really wanted. These steps, together, will take you to transformative innovation if done right.

The Asthma App: Always There for Me

At CFI we seek the latent needs in every customer experience. In our Asthma App, customers didn’t just want a stand-alone app to manage dosage and provide treatment reminders. Eventually the novelty would wear off, and they would stop using it. We knew that from previous outside research.

Further, as an industry, we have thrown a dizzying array of health and health care apps at customers. If you search the Apple iTunes app store for “health,” you’ll find more than 40,000 apps that work on weight loss or fitness or that address more general health questions and problems. There appears to be a high demand for them, with an estimated almost 700 million downloads for apps in this category in 2013. But in a report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, the researchers noted that the majority of the apps are spewing forth data that consumers cannot use to improve their health and well-being.

What our customers really wanted was the ability to avoid disruptive, time-consuming office visits—especially true for the 13- to 19-year-old age group we targeted. They also wanted to be able to contact care providers whenever a symptom changed or whenever they planned to do something or travel somewhere outside their normal routine so they could adjust their treatment. They wanted a live person to give feedback to them for any changes in symptoms. That contact didn’t have to be in real time—asynchronous was okay—but having that person there really helped them feel confident, and it motivated them to stick to their care routines as well. They wanted to use technology that they understood, which in this case was a smartphone. We hypothesized this, and we put the app together to confirm our hypothesis.

The Smart Mirror: A Lifeline to Loved Ones

For our Smart Mirror, the latent need was for not just the caregivers but also for the loved ones to be able to monitor the elder without disturbance during their normal routine or without the caregivers feeling like they were imposing on somebody who likely was an authority figure in their past. Again, we had to synthesize this latent need from our intuition of the complete customer experience; it wouldn’t have emerged from talking to the elders (or their caregivers) or from watching them in action. In this case, caregiver input helped us along, but we would do some assembly to get to the true latent need and final vision.

The Jack and Jill Room: Dressed for (Clinical) Success

One of the key tacit needs for the Jack and Jill rooms turned out to be very simple, and it was literally in front of our noses as we experimented with clinical room designs in our lab.

Almost amusing in its simplicity, here’s the story. During one of our experiments, a Mayo Clinic patient stopped her physician in his tracks and got him thinking: “When I’m dressed, I feel healthier than I do in a paper gown,” she said. Firmly and confidently, she equated the state of being clothed with the state of being healthy. “How can I talk about my health while sitting in a paper gown?” she continued and repeated: “When I get dressed, I feel healthier.”

Indeed, in the Jack and Jill rooms, patients spend most of their time discussing their health while fully clothed, not in the paper gowns. The setting feels more like a living room. We hypothesized that patients wanted more comfortable surroundings and wanted it to be easier and more discreet for family members, but this was a surprise that really teased out a more tacit customer need to be clothed and comfortable. This need carried through this project and became a learning for other projects.

If we didn’t strive to understand tacit and latent needs, we would invent a lot of faster horses. We would fine-tune the heck out of the patient office visit, making it as fast as possible with fresh magazines in the waiting room and designer gowns—and miss the big picture. We’d miss the true need or desire—that our patients would rather connect from somewhere with a care provider (not necessarily a physician) synchronously or asynchronously. But if instead we realize that if we meet this latent need to interact this way, our patients will be more positive about their health, and they will stay in contact more during health or when they need to manage a chronic disease. The outcome will be better health—and it will cost less.

In these cases, we would have missed tacit and latent needs if we had used traditional innovation methods. We had to take the extra steps to synthesize, create, and model these experiences—to “imagine” the experiences, before and after, to give the customers the “aha” and give our own organization the “aha.” We listen to customers just as everyone else does. We see them in action when possible and when it makes sense. But we go a step further—to feel the total experience, to imagine, and to put new ideas out there to feel their response.

Explicit, tacit, and latent.

Listen, see, and feel.

Discover and imagine.

Don’t Outsource This

This is important. You can’t just pay others to do this and forget about it. You can’t pay market research firms or other outsiders to really understand your customers. Why? Because the resulting picture will probably be limited to explicit needs.

The best innovations start by making the observations and doing the synthesis yourself. All members of the team, including management and organization constituents, should be involved, not just the marketers. We went the extra step to hire professional designers into the CFI team. This was the first time designers were embedded directly into an academic medical center. We did this because we didn’t believe that the experience assessment and resulting designs could come from outside. We didn’t want to miss tacit and latent needs. This should not be taken as saying that there is no role for outside companies; we certainly took advantage of the considerable expertise of IDEO and Doblin to get started, and we often still collaborate with them on projects. Rather, it is meant to point out that we listened to good advice, but we didn’t want others to do all our imagining.

Evidence, Please: The Scientific Method

So far, we’ve described the customer-centric but also business-constrained approach of design thinking. For many organizations, design thinking furnishes the core model for innovation.

With the complexity and the constraints of rigor and research naturally found in a health care environment, we must go further. Our innovations must fulfill the requirements of evidence and experiment, and they must meet the scrutiny of physician-scientists at once demanding of proven methods and skeptical of change. As a consequence, we must test, we must collect and present the evidence, and most of all, we need to maintain an exacting and unbiased approach.

This is where the scientific method comes in and is fused with other model components. The scientific method is based on measurable evidence, and it tests one variable at a time while keeping other parameters unchanged. It is, at its core, an unbiased approach to testing and proving a concept. The scientific method has four basic elements: making an observation, creating a hypothesis consistent with the observation, predicting something based on the hypothesis, and using experimentation to attempt to disprove the hypothesis. When the hypothesis can no longer be disproved, it becomes a conclusion that can be acted upon and communicated.

Multiple iterations may be used to test everything necessary, including new findings, ideas, and hypotheses from previous tests. The scientific method is not necessarily linear or circular. It yearns for solid, practical, evidence-based conclusions. Further, the learnings from one project or experiment are easily transferrable to another.

The scientific method entails a blend of testing, experimenting, observing, synthesizing, and documenting. We don’t advance any given framework for our teams to do this; we instead simply require a scientific approach and let them figure out how best to do it—the details vary by project anyhow. When presenting a project, we expect our teams to come to us (and to the physician community) with documented scientific evidence in hand. Suffice it to say that our project presentations are loaded with graphs and charts measuring the outcomes.

Keep It Moving Forward, Please: Project Management

In every project we enter, we start with the end in mind. It’s simple: get to prototype as fast as possible.

Of course, we’d like to get to implementation too, but we feel that implementation is too far down the road—a bridge to cross when we come to it. Why? Because if we do everything correctly up to that point, implementation should be fairly straightforward. Too, we don’t want to bog down the early stages of any project with the notion of implementing a set of ideas we haven’t even tested; for one thing, that would lead to predetermined conclusions, never a good thing.

At the same time, we recognize that the urge to innovate and the “golden moments” in seeing the success and “aha” of a project depend on getting something to work in the early stages. As most designers of personal technology products will tell you, the excitement really builds when you have a prototype in your hand to play with. The same principle applies to larger, and often more abstract, projects that you’d find in health care or other complex environments.

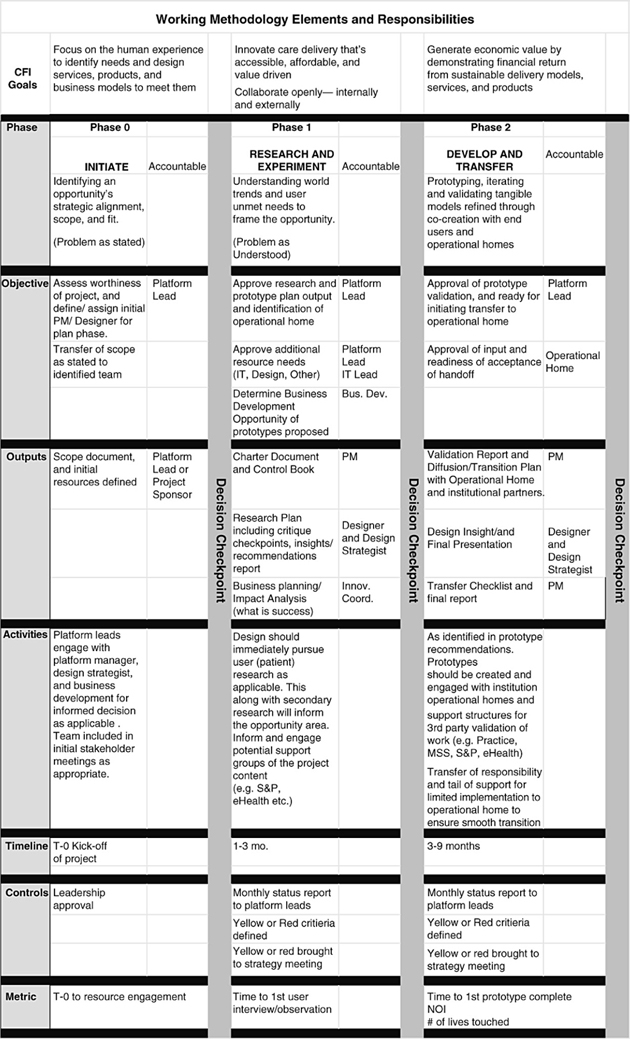

A Four-Step Approach

Our project management approach shies away from a template to follow in detail, though as we’ll introduce below, we do have one. Like the other principles in the Fusion Innovation Model, we try to keep this flow free and flexible in form as well. Different projects will require different levels of rigor in project management; we leave that up to the teams to decide. More important, we understand that the project flow is seldom sequential or linear; most projects will have some circular flow to test new ideas or outcomes from earlier tests. We want to allow that, in order to get to the best, not necessarily the fastest, solution. As we said earlier, we like to focus on what happens during the stages, not just the starts and finishes of each stage.

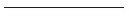

Figure 4.7 shows our conceptual innovation flow, which includes scanning and framing, experimenting, prototyping, and implementing. We should note that throughout this flow, we apply the principles of the Fusion Innovation Model consistently and continuously: design thinking, scientific method, and yes, traditional project management. And to repeat, these circles do not necessarily occur in sequence; there is usually a combination of linear and circular flow as the project team sees fit. For example, while scanning and framing, you can dip several times into the experimentation phase, as we did in the Jack and Jill Room project, to discover and round out tacit and latent needs.

FIGURE 4.7. CFI INNOVATION FLOW

Summarized, here are the four steps in the innovation flow:

![]() Scanning and Framing. In this step a project is conceived, and basic research begins. Teams are formed to collect data, apply customer understanding, define what further customer understanding may be required, and kick off the project. We feather in industry trends and develop personas representing a cross section of the groups we serve where it makes sense. In our detailed project map, we break this phase up into self-explanatory initiate and plan steps. The project is sized, resourced, and placed into the CFI Portfolio Roadmap to maximize connections with other projects, eliminate overlap, and leverage prior learnings. Internal stakeholders are identified and engaged. In this phase, we describe the hypotheses, what is to be tested and how it is to be tested, and give an overall sense of direction to the project.

Scanning and Framing. In this step a project is conceived, and basic research begins. Teams are formed to collect data, apply customer understanding, define what further customer understanding may be required, and kick off the project. We feather in industry trends and develop personas representing a cross section of the groups we serve where it makes sense. In our detailed project map, we break this phase up into self-explanatory initiate and plan steps. The project is sized, resourced, and placed into the CFI Portfolio Roadmap to maximize connections with other projects, eliminate overlap, and leverage prior learnings. Internal stakeholders are identified and engaged. In this phase, we describe the hypotheses, what is to be tested and how it is to be tested, and give an overall sense of direction to the project.

![]() Experimenting. The all-important experimenting phase is where we discover the reality of customer needs, and we test ideas and deliverables against those needs. The experimenting phase begins with research, best described as knowing what is known or what can be observed. Experimentation follows, and it is a process of getting at what is not already known and must be discovered.

Experimenting. The all-important experimenting phase is where we discover the reality of customer needs, and we test ideas and deliverables against those needs. The experimenting phase begins with research, best described as knowing what is known or what can be observed. Experimentation follows, and it is a process of getting at what is not already known and must be discovered.

Design teams are free to construct the experiments. Some experiments are in our labs; others are conducted within the practices or even outside of Mayo. The goal is to identify tacit and latent needs, through observation and data collection, and to start to wire together some of the possible solutions in low-fidelity ways like foamcore models. It is in the experimentation phase where “failure” occurs most often, or rather, where something doesn’t quite work but produces a learning that can be combined with other learnings to generate a new experiment. Experimentation leads us to create a prototype, a more formal and complete test of the concept in a live environment. Repeated and protracted experiments may arise from this phase; the timeline is simply “per project plan.” Research reports and prototype plans are outcomes of the experimentation phase.

![]() Prototyping. As we move into prototyping, we synthesize the discovery findings from experimentation, and we develop potential solutions or alternative future states. In prototyping, we validate and generate the proof of concept for the solutions.

Prototyping. As we move into prototyping, we synthesize the discovery findings from experimentation, and we develop potential solutions or alternative future states. In prototyping, we validate and generate the proof of concept for the solutions.

The prototype is a more complete, realistic, and on-location rollout of a concept designed to validate patient, physician, and staff benefits and to affirm the return on investment and financial metrics. Prototypes can be made in our labs or on location in community clinics or hospitals or, increasingly, in the customer’s home. They include working examples of technology, and they are fully staffed according to the model being tested. Finishing touches and some fine-tuning are typically applied to the deliverable.

![]() Implementing. Prototyping may go on for some time until the concept is solid; during this phase we begin to demonstrate it to various constituencies within Mayo. A project story is created and distributed through our communications engine (discussed in next chapter), and a plan is put together to acquire the resources, train the receiving practices, and roll out the project. In many cases, the operational owner is anticipated and engaged early in the project, making the implementation handoff far easier. As an organization, CFI is accountable for generating value and results—hence we never let up on the implementation lever!

Implementing. Prototyping may go on for some time until the concept is solid; during this phase we begin to demonstrate it to various constituencies within Mayo. A project story is created and distributed through our communications engine (discussed in next chapter), and a plan is put together to acquire the resources, train the receiving practices, and roll out the project. In many cases, the operational owner is anticipated and engaged early in the project, making the implementation handoff far easier. As an organization, CFI is accountable for generating value and results—hence we never let up on the implementation lever!

The Tools of the Trade

At this point we’d like to share some tools—or skills—that we feel are often overlooked in many innovation organizations. Teams often assume incorrectly that they do these things right. These skills are a focal point for us; we feel that they differentiate our approach to innovation and make it more robust, more tangible, and more likely to deliver results.

Using the Powers of Observation

There is no doubt that we are a visual culture. We would far rather see something in person. We’d rather watch a patient interaction with a physician than conduct a bunch of surveys about it. Why? Because in watching a real interaction, we feel we’ll get the true picture, and we can observe tacit needs and behaviors that never would be captured otherwise. So, we place a lot of emphasis on observation; we closely “shadow” the actions and activities we test.

Where appropriate, we like to record audio and video clips from these observations. We carefully document and discuss the clips openly to “synthesize and interpret” what we saw. We have special project rooms generally papered with Post-it Notes (Figure 4.9). We make the best attempts to find the big and small or detailed takeaways—most of all, the behaviors that surprise. Open eyes, open mind, and open thinking.

FIGURE 4.9. CFI PROJECT ROOM AND POST-IT NOTES

Brainstorming

Everybody does brainstorming, but not everybody gets a lot out of it. Brainstorming sessions can be dull, and results can be attenuated by organizational barriers and protocol.

We view brainstorming as a discipline, and we do it a lot. Our brainstorming sessions bring in diverse players, including members of the practice team. We encourage sessions to be visual and to “welcome wild ideas,” to generate a lot of them, and to link them together where possible. We do not, however, let brainstorming teams make decisions. Those are up to the project teams and their synthesis of experiment and prototype results.

Prototyping

We rely a lot on prototyping, and we believe we do prototyping well. Our prototypes are complete and realistic, yet fast to arise and fast to give us proof of concept. We’re not afraid to do a prototype a little “rough” to get it out there and see how it works. We get real patients, real physicians, real staff, real facilities, and real systems involved in prototypes as quickly as possible, and we don’t shy away from adjusting or tweaking the prototypes once they’re set up. Our prototypes not only prove concept but they also become vehicles around which to collaborate and for demonstrating our programs.

Innovation the Mayo Clinic Way: The Fusion Innovation Model

In this chapter we’ve presented an overview of the methods and guiding philosophy we use to imagine, initiate, and execute innovations into our practices. It’s worth summarizing key concepts before moving on.

In creating the Fusion Innovation Model, we’ve recognized that both design thinking and the scientific method are powerful tools but also have some limitations. The data-driven scientific method takes time and often requires large investments to be able to come to conclusions. Design thinking brings in a focus on our customers, our intuition, and our creativity, but its output can be hard to quantify. In large complex environments such as health care, change is often looked at as a threat, and mistakes can be very costly, so a highly objective approach is needed to bring change.

In creating the Fusion Innovation Model, we combined these disparate schools of thought. The process adapts to what we’re working on, but basically we integrate periods of intense experimentation, observation, and data collection with more intuitive and collaborative creativity sessions to complete our design thinking in a scientific manner. We may have several rounds of experimentation before we enter a prototype phase. We collect and analyze data from each of these experiments to frame the prototype, then use the prototype as proof of concept. We infuse a strong element of project management for coordinating and sequencing the tests and establishing the results. The resulting methodology combines the strengths of all three disciplines to achieve true innovation—all in a Think Big, Start Small, Move Fast framework.

All told, in the end, we’re really driven by the customer.

More specific takeaways:

![]() The CFI Fusion Innovation Model fuses the disciplines of design thinking, scientific method, and project management into a singular guiding approach to innovation.

The CFI Fusion Innovation Model fuses the disciplines of design thinking, scientific method, and project management into a singular guiding approach to innovation.

![]() Design thinking combines a deep understanding of and empathy with customers together with contextual creativity and a rational approach to synthesizing customer experiences and solutions.

Design thinking combines a deep understanding of and empathy with customers together with contextual creativity and a rational approach to synthesizing customer experiences and solutions.

![]() Deep customer understanding entails understanding not only explicit but also tacit and latent customer needs.

Deep customer understanding entails understanding not only explicit but also tacit and latent customer needs.

![]() Design thinking and deep customer research should be accomplished at least partly in house. However, using consultants to learn how to do it and to collaborate with is, of course, okay.

Design thinking and deep customer research should be accomplished at least partly in house. However, using consultants to learn how to do it and to collaborate with is, of course, okay.

![]() Design thinking is the secret sauce that makes innovation strategic and makes it really matter, while scientific method and project management make it possible.

Design thinking is the secret sauce that makes innovation strategic and makes it really matter, while scientific method and project management make it possible.

![]() Contextual creativity is about nourishing creativity, removing risk, and looking beyond your product into all areas where you can deliver customer value.

Contextual creativity is about nourishing creativity, removing risk, and looking beyond your product into all areas where you can deliver customer value.

![]() The scientific method removes bias by using measurable evidence to disprove a hypothesis or concept.

The scientific method removes bias by using measurable evidence to disprove a hypothesis or concept.

![]() Our project management approach combines intuition, experimentation, observation, collaboration, and deep prototyping to move a project forward, and it leaves a lot up to the design teams. We allow project teams to incorporate design thinking, scientific method, and project management principles as they see best to deliver a project.

Our project management approach combines intuition, experimentation, observation, collaboration, and deep prototyping to move a project forward, and it leaves a lot up to the design teams. We allow project teams to incorporate design thinking, scientific method, and project management principles as they see best to deliver a project.

From here, we move into the tools, skills, and processes we use to manage CFI and its presence in the greater Mayo organization. Chapters 5 and 6 cover what we call transfusion—the inbound and outbound communication and development and sharing of our innovative thinking. Chapter 5 explains our communications and knowledge management activities, and Chapter 6 explores our Innovation Accelerator. Both represent key skill sets and investments that set us apart from many other innovation organizations. The methods we use to manage and lead CFI inside a larger, complex enterprise are also revealing—and are covered in Chapter 7.