CHAPTER 1

THE POWER OF PURPOSE

Know Why

In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power.1

—Yuval Noah Harari, author of 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

Humans’ singular propensity for novelty means we are continually distracted by the new and shiny. Yet we have the ability to build an increasingly positive relationship with information. Understanding our purpose for engaging with information, the why, allows us to design the how of our information habits.

We can apply this in six important spheres of our lives and work: identity, expertise, ventures, society, well-being, and passions. For each, we need to follow a journey in which our purpose guides how we engage with information, and the information we find helps us clarify our intentions.

As we develop our capabilities in each sphere, we need to focus first on establishing foundational knowledge and then on keeping current on new developments. Each of these requires distinct information strategies.

Living in a torrent of information, don’t try to drink from the firehose more than you can or want. Balancing your purposes so you only undertake the achievable is the key to turning crippling overload into enabling abundance.

The objective of this book is not to help you find your life’s purpose. It is to help you thrive in a world in which information is the very essence of our lives and livelihoods. Yet the indispensable first step to live amid superabundance without getting lost is to be conscious about what you want in your work and life. Only this will allow you to understand the role of information in your life, discern what information is and isn’t relevant to you, and engage with information in the most productive way possible.

We each have a relationship with information, just as we have a relationship with money, food, and all the people in our lives, those we love and those we do not. The quality of our relationships is reflected in our mindsets, attitudes, emotions, and behaviors—in this case about our interactions with information. These can be positive and enabling, manifesting curiosity, joy of learning, desire to improve, drive to contribute, and sufficiency. Or they can be destructive, reflecting overwhelm, anxiety, guilt, or dread of boredom. As we understand these dynamics, we can learn to shape a better relationship with information.

Improving your relationship with information is at the heart of creating success and balance in your life.

Our brains’ ancient physiology makes this far harder than we would like. The first land animals developed a brain structure to help them forage for their daily diet. These foraging behaviors, based on the reward mechanism of dopamine, are in fact close to mathematically optimal strategies.2 As primates and then humans evolved, primitive brain structures such as the basal ganglia were complemented by more complex structures, including our prefrontal cortex, enabling even more refined seeking capabilities. Despite our dramatically more sophisticated cognitive abilities, the pleasure from dopamine that rewards seeking remains at the center of humans’ goal-directed behavior.

In the quest to understand our singular propensity for information, researchers proposed the idea of “information foraging.” They noted that “humans actively seek, gather, share, and consume information to a degree unapproached by other organisms.” Drawing on the science of food foraging, they found that precisely the same dopamine reward mechanisms apply to how we deal with information.3

Now that most of us can eat as much as we want, our in-built penchant for sweet, fatty foods has led to over half of all adults in developed countries being overweight or obese.4 In a similar vein, with unlimited information always at our fingertips, our dopamine-driven proclivity for novelty is effectively insatiable, leading most people to deeply unhealthy information habits.

Humans are best understood as information-processing animals. It is our nature to seek, make sense of the world, and invent. Our craving for information is a profound blessing, having generated all human progress. Yet it can also be a curse if we succumb to its darker manifestations. How we deal with our powerful predilections in a world of unlimited information ultimately defines our life.

You ARE the information you consume. Your choice of the information you take in determines whether you become who YOU want to be or who others want you to be.

In a society centered on information, the odds of feeling in control of our information habits are heavily stacked against us. As recently as 2007, the top 10 companies in the world by market capitalization included only one information technology company, Microsoft. In 2021, 8 of the top 10 were technology firms, and this is only if you don’t include Berkshire Hathaway, whose largest stock holding is Apple, and self-driving car company Tesla.

This leads to an economy in which “you are the product,” or more precisely, your attention is the most valuable asset. The most sophisticated and technologically advanced companies on the planet are spending billions of dollars to refine their ability to hijack your awareness. Given our brains’ propensity to constantly seek information, the default outcome is that our focus is always pulled to the latest enticing tidbit, and the information that enters our minds is largely what media, social media, and marketers want us to take in. But it need not be this way. We have the power to choose who we are and how we deal with information.

You need a reference point so you can make the choices throughout every day of which information you allow in. Understanding your purpose for engaging with information is a prerequisite for thriving amid excess. It is the foundation for developing and applying each of the other powers you will learn in this book.

We all have our own reasons for engaging with information. We might want to make a good living, fulfill our curiosity, build high-potential ventures, keep current on the state of our nation, learn about fascinating topics, invest successfully, have a positive impact on the world, or simply entertain ourselves. Everyone has their own desires and objectives.

You need to clearly understand your purpose for engaging with information, the WHY, to shape your relationship with information, the HOW of your habits and daily practices.

The word purpose comes with a lot of baggage, as at every turn self-help gurus exhort us to find our purpose in life. Yet whether or not we have discovered “the reason we were born,” we all have intentions that drive our actions through every day. Engaging with information in its myriad forms comprises the bulk of our waking lives, so knowing why we are doing it is essential for our information odysseys to benefit us rather than lead us astray.

Clarifying your intentions allows you to better define the relationship with information that will best serve you. Your information habits should be shaped by your unique priorities.

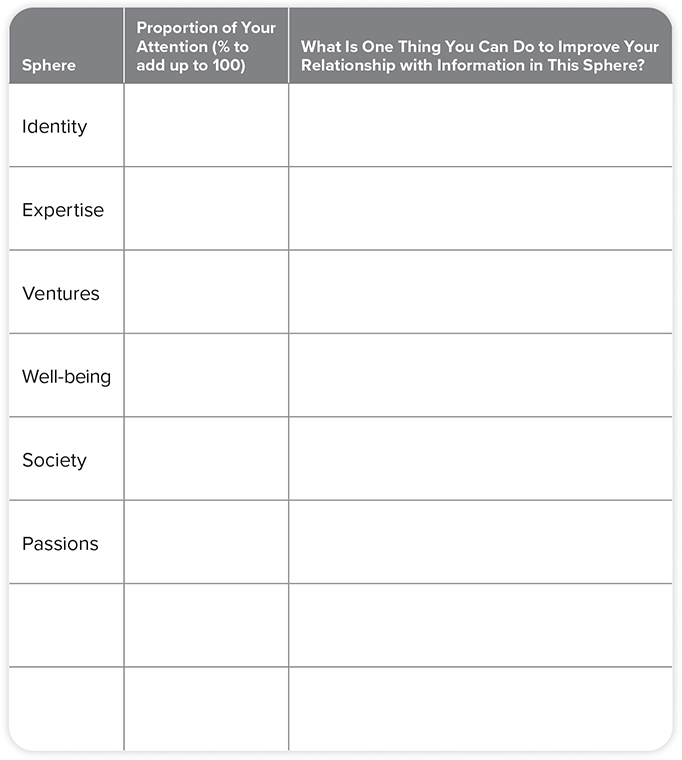

There are six primary spheres that define most people’s relationship with information, as shown in Figure 1.1. We have multiple purposes, rather than just one. Throughout this chapter we will explore how you can uncover your intentions, with the sole objective of helping you to engage more usefully with information. Don’t assume these six spheres are necessarily the most relevant for everyone. You might consider other domains more important. The exercises at the end of this chapter will help you reflect on what is most meaningful to you.

FIGURE 1.1 Six Spheres to Define Your Relationship with Information

Through the following four chapters we will examine how to enact a positive relationship with information. This chapter aims to help you understand your why. Knowing why you engage with information is necessary to achieve your unique objectives.

It is critical to recognize that your purpose, your why for engaging with information, is not a constant. You are changing, and the world in which you live is transforming at a pace that you can interpret as either exciting or terrifying. In fact, one of the most important reasons to be aware of news, developments, and emerging insights is that they allow you to clarify and evolve how you think about your path.

Make your life a virtuous cycle of applying your purpose to uncovering information and using the information you encounter to refine your purpose.

Learning helps us recognize what we want to learn. This applies to every sphere of our engagement with information, and to the elements that help us define an enabling relationship with information. Where it is most pointed is in developing the most central of the six spheres: our identity, our understanding of ourselves, who we wish to be, and our place in society.

Identity

Have you ever doubted the trajectory of your life? I dearly hope so. The only way to find your path is through a process of discovery, which by its nature means sometimes (or often) going off track, and then realizing it.

There were numerous times in my career when I doubted not just my path, but myself. At those times I had good jobs with prospects, but I and my work—or more often, my working environment—were evidently far from a perfect fit. I later described myself as at times feeling like “a fish out of water.” I questioned whether I was in the right place to create the life I desired. As I wondered whether I could find the right path for me, there were moments when I struggled and considered whether I might live a very ordinary life.

Even after I had launched my own business and more than ever directed my own fate, it wasn’t always apparent how to be true to myself. After my first book on knowledge-based relationships came out, many professional firms asked me to work with them on developing their key client programs and coaching their senior relationship executives. I believed strongly in the value of my work, but it wasn’t what most inspired me. Given the extent of corporate demand, I could have stopped there and developed a significant business in the space, but I was tantalized by my dream of becoming a full-time futurist, so I established an entirely new company to help leaders better see and create the future. On my journey, by dint of essaying many, many possibilities and paths, the arc of my life has become far clearer, though it absolutely remains one of ongoing discovery.

“I know who I am when I see what I do,” is how management professor Herminia Ibarra puts it.5 Our life’s journey is one of trying things to see what works for us. That is how we uncover what we’re good at and what brings us satisfaction or even joy.

If you can see your path laid out in front of you step by step, you know it’s not your path. Your own path you make with every step you take. That’s why it’s your path.6

—Joseph Campbell

If you have crystal clarity on what you wish to achieve in your life and the positive impact you wish to have on the world, you are blessed. It makes it far easier to filter information, as it is evident what is germane to your intentions and what can be ignored. You can focus utterly on the ventures that will fulfill your raison d’être. However, for the vast majority of people, finding their identity and purpose is a lifelong journey.

At the age of six, Jacqueline Novogratz decided she wanted to change the world. But she didn’t know how. She started her working career as a banker, only because it afforded her the opportunity to travel the world. As she worked in Latin America she was enticed by the color and vibrancy of the slums, meeting inspiring community businesspeople who didn’t use or trust banks. Inspired by this unmet need, she established a microfinance organization in Rwanda, moving past deep struggles to eventually found the global nonprofit Acumen. Her organization has invested over $100 million in transformative social enterprises that have helped over 300 million very low-income people.7

Speaking to a graduating class, Novogratz said, “We want simple answers, clear pathways to success. . . . Life does not work that way. And instead of looking for answers all the time, my wish for you is that you get comfortable living the questions.”8

If you recognize it for what it is, the quest to find your path can be as fulfilling as eventually finding it, for all its frustrations. It means you can and should be exploring more diversely, to uncover what resonates for you.

Curiosity is an intrinsic motivation, central to all human progress and learning. I believe deeply that the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake is a worthy human motivation, with as a wonderful bonus generating the most valuable innovation.9 To discover yourself, simply pursue what you find most fascinating.

If you are seeking to clarify your purpose and directions, that gives you license and motivation to explore more broadly than those who feel they have already defined their intent for their lives. Your adventures in information and ideas can feed your process of finding where you are called to invest your energy.

Whether you are close to certain or have almost no idea, try to state your life’s purpose as well as you can. It doesn’t matter if it doesn’t feel quite right. Treat it as a placeholder, one you intend to replace when you find something more compelling. You will find that even a tentative idea of your purpose immediately clarifies what information will support you and what behaviors will lead to the fulfillment of your purpose. Consider your information adventures as a voyage of refining your identity and life’s purpose.

Expertise

The single decision that will most shape your daily information habits is the choice of your area of expertise. As human knowledge progresses exponentially, there is only one way to keep up: select tightly defined domains in which you will develop profound knowledge. If you have too broad an ambit, others who are more focused will inevitably surge ahead of you. Selecting and developing your fields of expertise are necessarily at the center, not just of your career, but also of your relationship to information.

When Chris Anderson, at the time editor in chief of Wired magazine, succumbed to his passion to establish drone company 3D Robotics in 2009, he knew exactly who he wanted as his cofounder. He had recently set up an enthusiasts’ message board, DIY Drones, where Jordi Muñoz was sharing his profound knowledge of the realities of building drones. “He was just ahead of us all,” says Anderson.10 It turned out Muñoz had joined the forum as a teenager in Tijuana, Mexico. By focusing all of his energy and intellect, he had made himself into what he calls a “Google PhD,” a self-taught world-leading expert in this fascinating emerging technology, and soon president of a rapidly growing drone company.11

Some people proclaim themselves to be generalists. That is a very tough gig in an accelerating world. You have to earn the right to be a generalist, and the only path is through being a specialist. To understand the world at large, you need to have built a deep understanding of probably not just one domain, but several, so you can understand the linkages and connections, how they all fit together. I think I can fairly claim to be a generalist, but that is based on having worked in many roles in many industries in many countries over many years, along the way spending numerous extended periods developing specialist expertise in diverse areas.

That said, we need more than single-domain expertise. The corollary of intensifying specialization is that we must also excel at collaboration. Any specialization on its own has limited value. In an increasingly complex and interdependent world, the value of depth comes from its relationship to other disciplines and domains. To collaborate well, we need to have an understanding of other fields. The most productive entrepreneurs, executives, and scientists are voracious in the breadth of their interests to complement their area of singular focus. Patrick Collison, billionaire founder of payments company Stripe, is an omnivorous reader, devouring books on science, history, society, health, spirituality, economics, philosophy, technology, and biographies as well as business and classic literature.12

Top employers such as management consultants McKinsey & Company have long sought people with “T-shaped” skills, combining depth and breadth. In a complex world it can be useful to choose more than one area of expertise, to develop what are called “pi-shaped” skills. The shape of the Greek letter pi (π) suggests two domains for depth—the legs of the symbol—to complement the breadth of the top bar, instead of the singular focus of T-shaped people. While dividing your attention inevitably attenuates the depth you can attain, in an intensely interconnected world there is immense value to understanding complementary domains such as science and art, business and technology, design and coding, or many more specific pairings. As author Robert Greene says, “The future belongs to those who learn more skills and combine them in creative ways.”13

Selecting your areas of expertise is a lifelong journey. If you are going to dedicate much of your life to developing deep knowledge, you want to be not just interested in the topic, but captivated, thrilled to immerse yourself even if there were no reward. The more you learn, the further your interest will develop. When you select an area of expertise to focus on, assess not only current demand but also future potential, and over time monitor for signals of how its value may evolve. Helping your children to select their fields of study and work must take into account that some jobs will disappear and others will emerge, and the fact that your offspring too will blossom in surprising and sometimes wonderful ways.

Given its central role in your life and career, you need to be highly conscious in choosing your expertise and the breadth that complements it. Start by articulating your current positioning and direction. Always be open to evolving your chosen expertise, or even shifting to a completely new domain. Your knowledge, and especially the skills you acquired in developing it, will serve you well whatever you do next. As you go through the rest of the book, consider in precisely what domain you wish to become a world-class (or world-leading) expert, and design your information habits accordingly.

Ventures

In 2006 Facebook hired 23-year-old Jeff Hammerbacher out of Wall Street to establish its data analysis team, which would prove central to the burgeoning social network’s success. Hammerbacher later left Facebook to found data platform company Cloudera, which grew far beyond his expectations to be valued at over $1 billion in a matter of years.

Hammerbacher literally invented the term “data science” but found himself disappointed with how these incredibly powerful skills were being applied, ruefully observing that “the best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.”14 He yearned to turn his capabilities to a field he truly cared about. He thought that biomedicine was a field where it would be useful to apply data science and where he “probably won’t get bored.” Exposing himself more to the field confirmed his interest. A friend who had recently been appointed to run the Department of Genetics at Mount Sinai Health System helped create a position for him to explore data science applications in healthcare.

Hammerbacher had zero formal education in the space and a massive amount to learn, so as a self-professed autodidact, he set out to teach himself what he needed to know. He focused on reading textbooks and in particular review papers, which consolidate the research in a field, as well as setting up conversations with the most interesting people in the field to help frame his understanding.

“Review papers are key for me,” Hammerbacher says. “Finding a good review paper on a topic, and then figuring out who wrote it and then what their recent research is, and just finding kindred spirits, people who think like you do and being able to converse with them and interactively map a domain.”15 Establishing a broad knowledge of the field has led Hammerbacher to found and invest in a range of promising healthcare startups. He continues to push out the boundaries of health data and cancer immunotherapy, having coauthored 20 research papers.

In the initial stages of a venture, be it a high-potential startup or a local community initiative, you need to focus on framing your understanding with matching information strategies. As you grasp the essentials of the space, your relationship with information shifts to one of being consistently alert for relevant changes in your environment and emerging opportunities.

Success in ventures requires first foundational knowledge and then consistently keeping abreast of change.

The more precisely you can define your venture’s ambitions in terms of scope and impact, the better you can shape your relationship with information. What are the theses or assumptions on which your venture is based? In what industry sector or geography will you play? What social or other nonfinancial outcomes would you like to flow from the success of your business? Your responses to these kinds of questions will help determine information relevance.

When Jeff Bezos founded Amazon.com in 1996, his long-term aspirations meant that he closely followed every aspect of the flourishing ecommerce space, not just the book industry where the company commenced.

Society

“It isn’t that I don’t like current events. There have just been so many of them lately,” reflects a delightful cartoon in Marshall McLuhan’s book, The Medium Is the Massage, published well over 50 years ago.16

Indeed, most people want to keep current with developments, despite the daily onslaught. To participate fully in society, we need to be informed on the state of the world. Only this allows us to have grounded opinions on what might create a better community, nation, and world, and how we can best contribute, if we choose. We need to pay attention to what will lead us to understand the society we live in. Where possible we want to hear directly from people’s everyday experiences. However, we must inevitably, very carefully and selectively, draw on mainstream news media.

It is an instructive exercise to consider in depth why you want to see the news at all, and how it affords you a better life. Understanding our personal motivations is necessary to shape the most positive relationship possible with news. Is it so you can participate in your democracy through informed voting or voicing your opinion? Is it to have intelligent conversations about the state of the world with your friends? Do you want to know what can help your community? Are you simply curious about the state of humanity? At a time when many people’s relationship with news is highly dysfunctional, clarifying your intentions lets you adopt behaviors that best serve your purpose.

Be clear on what you want from news to transcend what news wants from you.

Philosopher Alain de Botton notes that “the news wants you to keep reading, but you also know there are times you should stop. The news is the best distraction ever invented. It sounds so serious and important. But it wants you never to have any free time ever again, time where you can daydream, unpack your anxieties and have a conversation with yourself.”17 Building a better relationship with news starts with understanding why you spend the time.

For many, some kinds of news are directly relevant to their work and the development of their expertise. Anyone who is seeking to have impact at scale needs a broad understanding of the state of society. This can entail following local, national, or international affairs, business, and social developments. However, this rarely requires frequent refreshes.

Those who work in media or politics need to keep constantly updated, but for most of us it is a huge time sink. The benefit of getting updates throughout the day as opposed to daily or even less often is minimal compared with the time investment. In shaping our relationship with news, we need to consider not just what news we want to engage with, but also how often.

Presuming that our life objectives include living a happy and healthy life, we need to acknowledge the mental health impact of overengaging with news. We all know that reported news is almost unmitigatedly negative; good news is rarely as exciting and click-worthy. Waking up to a barrage of pessimism every day inevitably shapes our outlook on life. Media analyst Thomas Baekdal observes that “the more you look at this, the more you realize that the way we do news today is seriously harmful to people’s mental health.”18 We need to be deliberate in how we engage.

To be well informed on the state of society you need to go far beyond the headlines, the latest political machinations, and tawdry stories that entice prurient interest. Seek insight into the behaviors of those from different generations or nations, uncover the different perspectives leading to conflicts, look for the incisive social perspectives so often expressed in the latest in arts and culture.

Take a step back and consider your place in the world. How much do you want to and need to know about what is going on? Why do you want to be informed? What are the highest priorities for you? Realize that it is all too easy to get sucked into the news vortex. Decide what will genuinely add value to your life and support your ability to participate in and contribute to a better society.

Well-Being

Undoubtedly the most direct impact of human progress we have experienced stems from advances in healthcare. Over the past century life expectancy has increased by over 30 years in most developed countries. Now that we have found ways to treat most common illnesses, many individuals and (hopefully) institutions are shifting attention from how to manage maladies to how to increase well-being and potential. An explosion of resources and information helps us on that path.

Fitness and health trackers have added massively to the personal information available to us. Many people monitor their time exercising, number of steps taken, heart rates, sleep patterns, and a wealth of other data, with some also tracking food and supplement intake, posture, and much more in seeking to improve their performance. If we use it well, this information can lead to immense positive change.

When speaker and author Chris Dancy turned 40, he had never eaten a salad, orange, or slice of watermelon. He weighed close to 300 pounds, on an average day eating 3,000 to 4,000 calories, drinking 30 Diet Cokes, and smoking two packs of cigarettes. Already avidly tracking his personal data, he dug deeper and found a correlation: he rarely smoked when he was drinking water, helping him drive down his smoking. He identified the specific types of exercise that had the most positive impact and the times of day they were most helpful. Dancy continued to dig into what behaviors drove improvements in his health. Five years later, having learned through data how best to adopt positive habits, he achieved his target weight of 175 pounds, in the process becoming vegan and giving up cigarettes.19 Information alone does not change us. We need to focus on learning what drives and shifts our behaviors.

Framing our relationship with well-being information begins by understanding who we care for and what we can do to help. How do you want to improve your health or potential? Are there loved ones you want to support?

Well-being goes far beyond health concerns. Our relationship with health information should be shaped by considering what will help us or others live the best possible life. Our emotional states, our social life, the cleanliness of our homes, our spiritual practices, the entertainment we choose, are all central aspects of our quality of life.

Our well-being includes not just our body, but also our circumstances, including our finances. As with other aspects of our well-being, we need to engage with information about both our own situation and the external environment: the fundamentals of personal finances or investment, where investment opportunities lie, tax implications, and more.

Our relationship with financial information can be fraught. If you have a family budget, checking whether your spending is on track at least every few days can be very useful, whereas daily updates on the state of an investment you intend to keep for the long term is not helpful. Unless you are a finance professional, avoid investments that require active monitoring. They can be enormous drains on your attention, and it is impossible to outperform those whose livelihoods allow utter focus on the markets.

Spend time to define the well-being outcomes you seek for yourself or others. Do you want to learn what will improve an ailment? Do you want to feel positive and happy throughout the day? Do you wish to reach an ideal weight to look and feel great? Do you want to improve your sports performance or even win an Olympic medal? Do you want to be sharp and focused to excel at your work or business? Consider the best way to engage with information to support your objectives.

Passions

David Solomon’s demanding job as CEO of storied investment bank Goldman Sachs doesn’t consume his whole life. He has a side gig as a DJ mixing electronic dance music, playing at popular festivals and boasting over 700,000 monthly listeners on his Spotify channel.20 His passion requires him to keep on top of the latest music releases, scouring new releases and mixes to be current in rapidly evolving music fashion. The thrill of performing to a pulsing audience is founded on absorbing information of a quite different nature than that required in his day job.

We all have passions that transcend our work lives. For many, sports are a defining interest, in some cases leading to obsessive poring over statistics and the manifold potential predictors of team performance. Others choose to follow the lives and fortunes of musicians, movie stars, or other celebrities, the latest in art or theater, or indulge in more specialist interests such as train or plane spotting, or collecting stamps, period furniture, classic dolls, or any of a universe of possible interests.

Any of these passions drives a quest to be informed of the latest or to develop deeper understanding. These fascinations are deeply human—they fulfill intrinsic needs. Having diverse interests make us more well-rounded than those who focus too narrowly. We need to acknowledge that extracurricular interests beyond our work, studies, and ventures need to be balanced with our other information priorities. Yet for many they are absolutely part of a healthy information diet, in following what intrigues us and absorbs our attention.

Acknowledge your interests and obsessions that require information. Hiking or going fishing doesn’t need much. Collecting contemporary art or following sports, for example, does. Consider what information will most support your enjoyment, its place in your broader information habits, and the time and attention you should dedicate relative to your other purposes.

In the Flow

To slake your thirst besides a torrential river, you don’t try to drink the whole river. You dip in a cup and take a sip. You might endeavor to fill your container with the best quality water from the stream, but you don’t attempt to drink more than you need. It wouldn’t make you feel better, and it is in any case completely impossible to take in more than a tiny fraction of the flow.

We are finite beings living amid infinite information. Even though our brains are the most extraordinary natural phenomenon from the known universe’s profusion of wonders, our cognition is severely restricted. However much we may want to soak in more information, our biology has hard limits. It is not useful to attempt the impossible; we need to acknowledge and work within our brains’ constraints.

In the words of poet Rumi, “Life is a balance between holding on and letting go.” For our relationship to information to be enabling rather than destructive, we need to gracefully accept our limitations.

Letting go of trying to keep up transforms crippling overload into enabling abundance.

We are multifaceted beings, with priorities across work, family, community, health, and beyond, all of which require information to accomplish. When you consider your many purposes, you will likely find you are setting yourself up to try to do more than is reasonable, or perhaps even possible. You have choices to make.

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery,” wrote Charles Dickens in his great novel David Copperfield. As for money, also for information. Trying to do even slightly more than you can creates an immediate feeling of overwhelm. In contrast, maintaining your intentions for information intake a fraction less than what is realistic generates a sense of liberation.

Whatever your purposes are in life, they will be furthered by a constructive relationship with information. Central to achieving that is simply understanding your relative priorities, allocating your time accordingly, and not undertaking more than is possible.

Amplifying the Power of Purpose

This chapter has offered a framework for you to clarify your intentions across the major domains of your life. Take the time to reflect on these. You will be amply repaid by any effort you spend developing a positive, enabling relationship with the information that is at the heart of your work and life.

In coming chapters, you will apply your evolving apprehension of your intentions. In Chapter 2 you will learn how to frame and develop your understanding of your priority topics; in Chapter 3 you will develop filtering criteria based on your objectives; while in Chapter 4 you will create information routines that embed your priorities in your daily schedule.

EXERCISES

Purpose

What are your current best articulations of your life’s purpose, your intentions of what you wish to achieve, that will help define your engagement with information?

The Priority Spheres of Your Life

In this chapter I suggested six spheres to consider your relationship with information. Perhaps there are other spheres of your life that are important to you; if so, add those to the list that follows.

For each, indicate the relative importance. Don’t try to allocate more than 100 percent of your attention. If something is more important, then you have to reduce from other spheres. Go on to consider for each sphere one action or habit that could improve your outcomes. Come back to this after you have learned techniques from the rest of the book.

Your Expertise

Consider your current and potential future expertise. For each domain assess your current level of expertise on a scale of 1 to 10 to help gauge what may be required to develop it.