CHAPTER 4

THE POWER OF ATTENTION

Allocate Awareness with Intention

At the end of your life, looking back, whatever compelled your attention from moment to moment is simply what your life will have been.1

—Oliver Burkeman, author of Four Thousand Weeks

Your attention is your most precious gift, but it is a finite resource and constantly being pulled away from you by today’s perpetual distractions. Humans cannot truly multitask; the steep cost of switching between tasks means the longer we can remain in a single attention mode at a time, the more effective we will be.

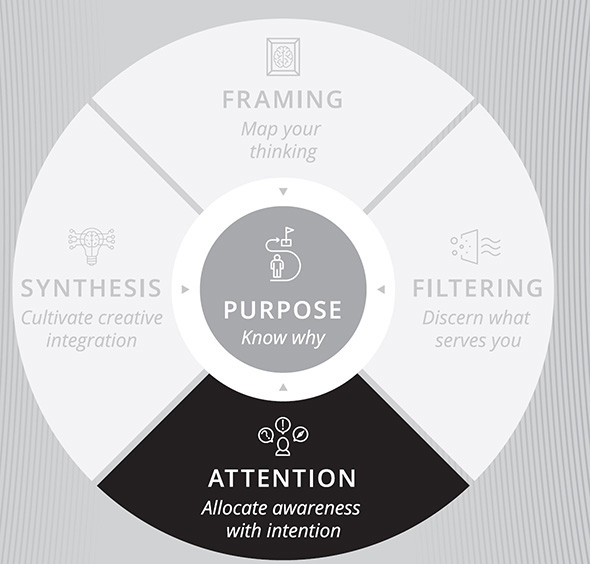

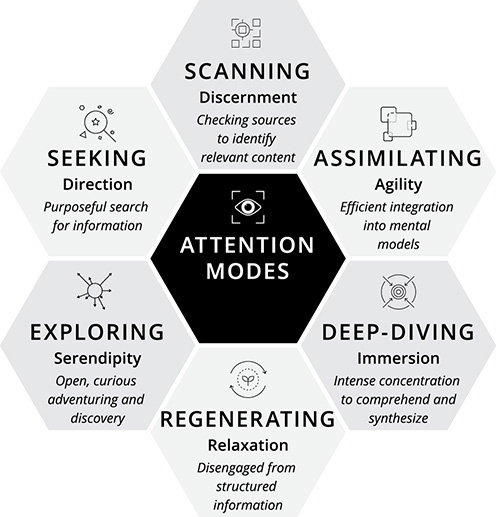

Attention is not one thing; there are six different attention modes that we need to understand and use judiciously to maximize our minds and capabilities: Scanning, Seeking, Assimilating, Deep-diving, Exploring, and Regenerating.

Establishing enabling information routines that set timeboxes for your attention modes will maximize your productivity and outcomes. Just as we can fortify our body through consistent training, we can strengthen our attention with concerted exercise.

On June 9, 2008, Steve Jobs, standing in his signature black turtleneck and jeans in front of an enthusiastic crowd at Apple’s annual Worldwide Developer Conference, announced the iPhone 3G. It featured (at the time) superfast 3G access, location services, the freshly launched App Store with a wealth of third-party applications, and to boot, an affordable entry price of $199. This was the true dawn of the smartphone era, drawing in what would be before long the majority of the population to constant information access throughout their waking hours, with a continuous welter of penetrating notifications drawing people back to their devices.

More recently, 47 percent of Americans (no doubt accurately) considered themselves addicted to their cell phones, while 70 percent check their phones within five minutes of receiving a notification.2 Not surprisingly this behavior tends to fragment our attention, as we are exposed not only to constant interruptions, but also the ever-so-sweet temptation of instant diversion with friends’ and celebrities’ updates.

Goal Interference

Humans are distinguished from all other animals by their highly evolved goal-setting abilities. We must be in awe at what humans can achieve when they set their minds to it. However, on our paths to our desires we all experience what is called “goal interference,” not least from the infinite distractions that can lead us astray.

Unfortunately, “our cognitive control abilities that are necessary for the enactment of our goals . . . do not differ greatly from those observed in other primates, with whom we shared common ancestors tens of millions of years ago,” write neuroscientists Adam Gazzaley and psychologist Larry Rosen in The Distracted Mind.

The reality is that our cognitive control is highly limited. Our brains are not designed to do what we want in today’s saturated information environment. Gazzaley and Rosen believe that “this conflict is escalating into a full-scale war, as modern technological advancements worsen goal interference.” The bounteous distractions in our environment are, not surprisingly, massively impeding our ability to achieve our objectives.

The Cost of Task-Switching

Do you think you are good at multitasking? If so, you’re wrong. Recent advances in neuroscience have allowed us to observe brain activity while we are engaged in multiple tasks. They verify that humans simply do not have the ability to engage in multiple activities simultaneously. When we think we are multitasking, our brains are in fact rapidly switching between tasks. This entails a high cognitive overhead, so the more you divide your attention, the lower your performance. In fact, those who consider themselves to be good at multitasking consistently perform worse on concurrent tasks than those who don’t usually attempt to do this.3

The steep cognitive price of task-switching means that to process information efficiently we must keep to single tasks for extended periods. This doesn’t mean that we need to be automatons, never distracted by what is around us. Many tasks, such as watching entertainment, cooking, browsing magazines, or walking down the street, do not require our undivided attention. Yet to achieve anything of note we need focus, spending stretches of time in consistent types of attention before moving on to the next task.

The Six Attention Modes

Our brain has many different states, depending on the context. Our neurological patterns will vary dramatically depending on whether we are watching a film, studying for an exam, browsing social media, having a shower, or each of a host of other activities.

We can’t—and don’t want to—sustain any of these states of mind for excessive periods. Each has its place in enabling us to create the lives we want. The trick is in choosing when we can most usefully apply each frame to our information odysseys.

How you allocate your attention is a defining choice in your life.

Many writers imply that focus is a singular state, in that we are either focused or not. In fact, there is a wide range of mental states and each offers a different locus and breadth of attention.

There are six distinct activities that play a critical part in our ability to thrive on overload. Each one is associated with an attention mode that optimizes our information usage, as shown in Figure 4.1. The diagram depicts each information activity and its quintessence, along with a brief description.

FIGURE 4.1 The Six Attention Modes

Each of the attention modes has an important role to play in our daily immersion in information. The critical issue is in the balance between them, ensuring that each one is used when appropriate. Throughout each day, we need to allocate our attention with clear intention.

Blocks of Attention

As we have seen, there is a dramatic mental cost to switching between attention modes. Reducing the frequency of switching between modes is one of the most important drivers of information mastery. Every distraction and transition detracts from the value of our current activity.

The longer you remain in a single attention mode at a time, the more effective you will be.

The greatest value comes when we deliberately allocate time for each of the attention modes and stick to that activity for that period. If while we are Deep-diving an idea comes up, we should make a note so we can forget it and come back to it later. If we are Exploring and identify a valuable resource, it is often better to park it for time allotted to Assimilating. If you are Seeking specific information and stumble across a fascinating list of tangents, bookmark it for when you are Exploring. Creating structure in your information immersion will pay enormous dividends.

To become true information masters, we need to build routines that allow us to keep on top of change while also leading balanced, happy lives. We can do that by allocating in our daily schedules time to engage in each of the attention modes in ways that support our purpose and goals.

Later in this chapter we will explore how to develop an information routine that empowers you each and every day. Before that let us examine the six attention modes in the rough order many of us use them: Scanning, Seeking, Assimilating, Deep-diving, Exploring, and Regenerating.

Scanning

Every day, every hour, every minute a bounty of new information is generated that might be not just relevant to you, but vital. If you work in any domain that moves faster than a slug’s pace, you need to scan broadly and consistently to ensure that you are aware of what is important.

The mechanics of what to scan was covered in Chapter 3, in selecting a portfolio of information portals and sources to keep you well informed. The most important part of filtering is establishing the structures that expose you to useful and correct information. In this chapter, scanning addresses when you survey the world to uncover what matters, and the state of mind to do this effectively.

Discernment is the defining characteristic of effective scanning, in deciding whether you will skim over something or take a closer look. Given the profusion of information, skimming through our sources must be a highly accelerated process, involving a continuous flow of rapid-fire decisions. Our minds need to be nimble, happier to skip ahead than get bogged down. As such, goal-oriented scanning is often best done when alert.

Efficient Scanning

In a fast-moving world you need to scan for updates regularly. The mistake many make is doing this consistently through the day. If you are a stockbroker or a journalist, you need constant updates to respond to market movements or report on a breaking story. Most of us don’t need to be so close to the edge of change.

Often the single behavior shift that can most improve your information habits is checking for news updates less frequently.

Our deep human propensity for novelty can make it hard not to be always looking for the latest. If we can bring ourselves to cordon off most of our scanning activities to specific, limited periods, we can garner substantial benefits. The task is being as effective as possible in your regular checking of sources. Here are a few useful rules:

Stick to your chosen portals and sources. Scanning is a delineated activity; aim to do it efficiently. If after you have done your scheduled review you want to fit in some Exploring, that’s fine, but start and finish your defined scan first. As you assess the quality of your feeds or uncover other interesting sources, delete or add to your list of sources you check regularly.

Assess headlines first. This has become much harder as internet headline writers are taught to tease but not disclose the article’s point. This comes back to selecting the information sources you will use regularly. If they require you to click through the headline to find out what the article is about, it is an inefficient source and you should likely switch to sources that provide a clearer indication of article content in their titles.

Bookmark for later reading. Scanning is about quickly and efficiently going through your core sources and identifying the content that is worth spending time on. Don’t get bogged down in reading articles that require time and dedicated attention; set these aside for when you have the right frame of mind for Assimilation, and complete your Scanning process.

Constrain your scanning time. Assimilating valuable information is more important than Scanning and should take more of your time. If you are spending all your time looking for what’s interesting without delving into the detail you will never build depth.

Seeking

The creation of modern search engines was arguably almost as important as the invention of the internet. Now when we want to know something, we only need ask.

While web search is our usual mode of Seeking, we should also consider other approaches. As you have learned, people are often your best resource in finding the information you need. We should not forget that there are libraries full of marvelous books that are not available in digital form. Yet their catalogs are almost always available digitally, allowing us to search for and uncover these gems, potentially followed by a library visit for a Deep-diving session to mine their insights.

As with every focus mode, carve out a period for your stint of Seeking and park for later those resources that merit more attention. Seeking can very easily end up as an Exploring session, leading you to places that may be enthralling but not serve your objective, so as with all attention modes, keep focused! While you are Seeking, follow these principles:

Be clear what you want. The fundamental mental frame for Seeking is direction. Without clarity you risk wandering aimlessly amid the myriad enticing tidbits you will encounter. Having a specific idea of what will be useful to you makes it easy to assess the relevance of what you find.

Scan broadly. The first step is to find as many resources as possible that are relevant to your search. Depending on what you’re looking for, don’t limit yourself to your usual search engine. Use different search engines, and when appropriate use academic search engines such as Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, or ResearchGate. I use an initial set of search terms and open tabs to all of the pages that seem potentially useful, based on their title and the meta text in the search engine. I then try to identify alternative search terms, since authors and publishers could use different words from the ones I start with, until I have uncovered the most promising starting points.

Delve deep. For some information quests you need to go beyond the surface. When entrepreneur Martine Rothblatt was striving to identify a cure for her daughter’s disease, she adapted a technique called “shepardizing” she had learned in her legal studies. The name comes from Shepard’s Citations, which tracks every mention of a legal case or statute. For every promising medical paper Rothblatt found, she went to its citations, and in turn to their citations, creating a spiderweb to reach the vast majority of pertinent published content.4 The process is deeply time-consuming but enables thorough discovery of the most relevant sources. The treatment Rothblatt uncovered not only saved her daughter’s life, but also provided the foundation for her company United Therapeutics, which has since been valued at over $9 billion.

Narrow swiftly for later assimilation. Go through all of the resources you have uncovered, quickly winnowing. If you have opened multiple relevant tabs, quickly scan through each to see whether they may have valuable information. If they are sufficiently promising, bookmark them for later Assimilating or Deep-diving sessions. If there are only one or two points of interest, note the ideas and move on. Be efficient at assessing the potential value of content so you can allocate dedicated attention to what is worth absorbing.

Once we have found intriguing content through Scanning and Seeking, we need to integrate it into our thinking. This requires a shift of gears; Assimilating is a distinct state of mind.

Assimilating

Two years into his stint as junior senator of Massachusetts, an ambitious John F. Kennedy took the time to drive with his brother Bobby one hour each way to attend a weekly evening course at Johns Hopkins University titled How to Read Better and Faster.5 Later President Kennedy claimed to read 1,200 words per minute (he was also reputed to hold a world record for talking speed, peaking at 327 words per minute in one of his speeches). He invited speed-reading entrepreneur Evelyn Wood to the White House to teach his staff, with Richard Nixon following suit and Jimmy Carter also taking the Evelyn Wood course.6

Even for those of us who do not have the demands of being president of the United States, speed-reading is a tantalizing concept, promising the ability to absorb content far faster than the usual rate of 200 to 400 words per minute. Yet the issue is not so much how fast you read, but how much you take in. Assimilating means integrating ideas into your thinking, truly absorbing and comprehending them. Better assimilation is not necessarily faster. You need to intelligently adjust your pace so that you can engage fully with the most worthwhile ideas, to make them yours.

Switching Gears

A race car driver will put her vehicle in top gear for straight and predictable stretches of track, then downshift as she reaches the curves that require precise attention and control. In the same way, as we read we should be ready to switch gears between racing through less relevant ideas and slowing dramatically where we want to fully understand the content.

Uncovering interesting content or information has only limited value by itself. You need to take the content and ideas and integrate them into your frameworks and mental models. Allocate specific time for Assimilation, rather than trying to fit it in whenever you stumble across an article or resource that you want to absorb. This can be whenever suits—for example, while eating, commuting, or exercising. Nir Eyal and Marina Gorbis both absorb much of the content they have previously selected through audio while working out at the gym.7

The quintessence of Assimilating is agility. You have identified content that you have decided is worth your attention. But you don’t yet know how much value there is in the content you are delving into. You have to be nimble to extract value as efficiently as possible.

How to Comprehend Faster

What superpower would you choose? Flight? Telepathy? Laser eyes? When Bill Gates was asked this question, his simple reply was, “Being able to read super-fast.”8 You can make substantial progress toward that aspiration by following (and practicing) these four principles:

1. Hone visual reading skills. We can process faster visually than through any other sense. It is critical to eliminate any subvocalization while we read. Taking in larger chunks of text at a time by expanding your field of vision is a critical component of effective reading.

2. Minimize fixations. We process visually through what are called saccades, in which our eyes fix on one place, then move to the next. When reading, our objective is to increase how much text we can absorb in each fixation. Developing this skill takes work but pays off in spades. You want where possible to take in a whole line or group of lines in one saccade, not moving your eyes from left to right. To make this easier, where possible reduce line width: if using a tablet, read in portrait rather than landscape mode; on computers reduce the width of the browser window.

3. Make sense of the whole. When you are reading to extract value you should rarely start at the beginning and go to the end. The opening sections of a book or long article will hopefully neatly summarize the content, while the end may provide a recap or conclusion. For some kinds of books, I find it useful to start by skimming the entire text in 15 minutes or so to get a sense of the overall structure and argument and to identify the sections that I expect to find most interesting.

4. Guide your pace. The reading habit that slows us the most is regression, going back to look at what we have already read. To get into the habit of a consistent pace, move your finger or a pencil steadily down the page to guide your eyes. When Assimilating, we should vary pace according to content. If you are already familiar with the ideas in the text, you can speed up; if you encounter interesting concepts, slow down to absorb them.

Observing these simple principles can immediately and significantly accelerate your pace of text comprehension. If you’d like to go deeper into improving your reading, check out the Resources for Thriving at the end of this book.

Note-Taking and Framing

The function of Assimilating is integrating ideas into your frameworks and mental models. In Chapter 2 we discussed the immense value of taking notes, and the value of making them in connected note-taking systems that link concepts to other references.

Taking notes not only allows you to capture any specific insights you gain and readily find content again. The very act of writing a note also helps you make sense of an idea and impress it on your mind. Many people who read material end up unchanged aside from a vague recollection of what they went through. Anyone who makes a note when reading is effectively integrating the content into their mental models.

Making notes is more than absorbing ideas; it is the process of making them yours.

As Edgar Allan Poe put it, “Marking a book is literally an experience of your differences or agreements with the author. It is the highest respect you can pay him.”

Deep-Diving

Our minds wander. This is not just from time to time; it is almost constant, leading scientists to describe this as the “default mode” of our brains.9 We spend most of our waking hours at the surface. Sometimes we need the intent and will to dive deep. Arguably the biggest division among us is between those willing and able to immerse themselves in ideas and thinking for extended periods, and the majority who perennially skim across the superficial.

In the state of Deep-diving we can absorb content for true comprehension, deliberately discern patterns, identify new connections, and refine the structure of our frameworks. This is a time for purposeful sense-making, exploring perspectives, and laying the groundwork for effective decisions.

“As the competitive and technological landscape continues to shift at an accelerating rate you will require more time than ever before to just think,” says Jeff Weiner, executive chairman of LinkedIn. “That thinking, if done properly, requires uninterrupted focus; thoroughly developing and questioning assumptions; synthesizing all of the data, information and knowledge that’s incessantly coming your way; connecting dots, bouncing ideas off of trusted colleagues; and iterating through multiple scenarios. In other words, it takes time.”10

Indeed, there are two foundations to Deep-diving: allocating sufficient blocks of time and accessing the right frame of mind. Deep-diving is several levels more intense than most information engagement; it is a distinct state. Some, such as software developers, writers, or researchers, may need to get into this state every day. However, everyone who wants to thrive in our world needs to carve out regular times to dive into the depths of forming useful mental models.

We should treat this as a distinct, special state. In other focus modes you might choose to keep yourself open to important notifications. Deep-diving is a state of total immersion. There are four critical steps to being able to dive deep:

1. Carve out sufficient blocks of time. It takes your mind a while to get focused. Few can switch on instantaneously. The minimum time for a deep-dive session should be an hour; many recommend aiming for three hours or so. Consider the best time of day for you to be hyperfocused based on your daily cycles. It also depends on your circumstances: for example, whether you have children to get to school, or your typical workday is so fragmented that you can’t carve out extended periods during normal working hours.

2. Design your environment. Create a space in which you can be completely comfortable for an extended period. Be sure the ergonomics are good, with a chair in which you can sit with a straight back or at a standing desk, with your screen close to eye height. Avoid using a laptop without an external screen, as you have to bend your neck to look down. Set up lighting that is comfortable.

3. Eliminate all interruptions. In Deep-diving you eliminate all distractions. Close your email; turn off phones and all social media notifications. A variety of apps such as Cold Turkey or Freedom allow you to shut off all applications and notifications for the period of your choice. If you’re writing, distraction-free writing apps like FocusWriter support complete focus. Block out the time in your calendar so colleagues can see you’re busy, and make sure anyone in your office or household knows that you should be interrupted only for something highly urgent.

4. Refresh with regular breaks. We cannot sustain focused attention for extended periods; you need to rest your mind periodically. The basic rest-activity cycle (BRAC) theory states that we go through regular cycles of alertness and relaxation lasting around 90 minutes. Others suggest shorter focus times: for example, in the Pomodoro technique you work for 25-minute stints with 5-minute breaks. See what works best for you. What is critical is substantially changing your state and activity during your breaks. Be sure to stand up, walk around, look outside, perhaps do some breathing exercises. Don’t browse news or social media on the same device you’re using for your work—that won’t refresh you.

Soundtracks for Deep-Diving

When Michael Lewis is preparing to write his books, which have included Moneyball, The Big Short, and many other bestsellers, he carefully compiles the soundtrack for the project. He takes suggestions from his wife and children, building a wide variety of upbeat tracks that he then plays relentlessly on repeat throughout his book writing.

He writes with his headphones on so he can’t hear anything going on around him. “It’s a device for shutting out other interruption and for creating kind of an emotion, a feeling,” Lewis says. Because he has heard each track hundreds of times, it ceases to register mentally. “I’m just in my own space and I kind of cease to hear the sound.”11

Futurist and author Amy Webb is an aficionado of brown noise, random noise mainly in the lower spectrum, which can sound like the surf or wind. “Because I’m more sensitive to higher frequencies, brown noise helps me focus intensively. It’s amazing how well it works,” Webb reports.12

When we are Deep-diving, soundtracks can help us to focus and drown out sounds around us. Some people prefer silence, but this requires a workplace away from any disturbances, a luxury not available to everyone. Comfortable noise-canceling headphones playing the right soundscape can create an oasis for undisturbed thinking, even in busy environments.

Some companies profess to have created music that specifically helps you focus. You should experiment and find what works best for you. Music is not just to drown out background noise, but also to create a positive mood; it can help you not just focus but also enjoy your Deep-diving sessions.

Exploring

Humans are intrinsically explorers. It is not just pleasurable to meander through the back alleys of the web and beyond; it can also be extremely valuable as we stumble upon insights or perspectives that we would never have found if we were overly focused. Rather than demonize “surfing,” we should understand it as an invaluable element of our information routine. To make our far-flung reconnoitering useful we need to shift our attention from tight focus to the peripheries.

There is a reason that houses with expansive views, from hilltops or looking out over the ocean or a lake, attract premium prices. There is something uniquely attractive—and beneficial—about being exposed to broad vistas. Andrew Huberman, professor of neurobiology at Stanford University, says that when we go into panoramic vision—for example, by seeing horizons or walking down the street—it has a calming effect on our nervous system and disengages our vigilance of attention, the tight visual focus that we usually have, for example, when we look at screens or are indoors.13

You can readily practice peripheral vision. Stop reading, look straight ahead, and see what you can notice at the edges of your field of sight. Try gently redirecting your visual attention to the edges of what you can see, without moving your eyes. You will likely find yourself calmer and more relaxed. This simple activity puts you in a state of mind similar to meditation. As you walk around during the day try deliberately entering panoramic vision, directing your attention beyond what is in front of your eyes.

Broader visual perception, perhaps not surprisingly, can expand our conceptual understanding. Studies have shown that people who broadened their visual field were more likely to experience insight in solving problems.14 See more broadly, and you will think more broadly. The ability to expand your visual perception also enables faster reading by minimizing fixations and allowing you to more readily absorb concepts.

Enhancing Serendipity

Serendipity was once voted by Britons as their favorite word and is said by interpreters to be one of the English words most difficult to translate.15 Meaning the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries, it comes from the enchanting tale of The Three Princes of Serendip (the ancient name for Sri Lanka), a fairy tale in which the eponymous three princes enable felicitous connections, not by pure accident but by actively creating the conditions for them to happen.16

The point about the origin story of the word is that serendipity is often not fortuitous; you can behave in ways that make it more likely to occur. Here are a few practices that can make it more likely that you experience fortune in your unfettered information adventures:

Take the path less traveled. “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference,” wrote poet Robert Frost. As we turn off the information highways into beguiling byways, in Exploration mode we can give ourselves permission to go, not necessarily where fewer people wander, but certainly where we usually don’t go.

Keep following your fascination. In exploration mode you can follow the intriguing link that you might pass over when you’re in a more focused state. If you find something interesting, keep following it down the rabbit hole, or use it as inspiration for another starting point. Keep moving unless you find gold. The more diversions you take, the more likely you will uncover inspiration.

Search in different places. If you’re used to searching in a search engine or YouTube, try podcasts, Twitter, Pinterest, academic search platforms, foreign language search engines, or your books, if you keep them digitally. Investor Sanjay Bakshi regularly seeks ideas in his own book collection, saying, “You sometimes discover things that you didn’t know existed—the serendipitous discovery of wonderful words of wisdom about a certain topic in your Kindle library is amazing, and when that happens, I have my eureka moments.”17

Start with an intriguing person or word. Sometimes I search on nonmainstream platforms using a word or unusual combination of words that might lead to something interesting yet surprising. Words I have used include (of course) “serendipity” as well as combinations of terms germane to my research. A valuable and often fun exercise is to select an intriguing person who evidently thinks differently from you as a starting point for exploration.

Cultivate your faculty for serendipity. Learn by giving yourself feedback. When you are exploring, register mentally when you encounter something surprisingly interesting or useful. How did you find it? What might you do to make this kind of discovery more likely to happen again?

Regenerating

Stephen and Rachel Kaplan met when studying at Oberlin College, an Ohio liberal arts institution, swiftly recognized themselves as soul mates, and were married at the ages of 21 and 20, respectively. They went on to complete their doctorates in psychology at the University of Michigan at the same time and spent the remainder of their careers working and collaborating, both becoming full professors at the Ann Arbor university.

In the first decade of their careers the Kaplans focused primarily on traditional psychology research topics such as memory and arousal, until the USDA Forest Service engaged them to study the benefits of a wilderness challenge program. Stephen described the results as “incredibly impressive,” sparking a transformation in their lives to focus on the value of nature for human cognition.18

The Kaplans proposed that there are two types of attention: directed attention and fascination. Overuse of directed attention, which is what we primarily apply in our everyday world of information immersion, is not sustainable, leading to “directed attention fatigue.”19 Being in nature draws our attention, not in a highly directed fashion, but in fascination with the infinite variations and beauty in any natural environment. Subsequent research led to the development of attention restoration theory, which focuses on how different environments, particularly natural, help our limited attention capabilities to regenerate.

Stephen later drew a distinction between “soft fascination” and “hard fascination.”20 The fascination you feel in nature is gentle, allowing other thoughts to emerge and flow as you contemplate your environment. Other types of fascination, such as watching movies or sports events, absorb your attention and prevent thinking about other things.

“Another day of staring at the big screen while scrolling through my little screen so as to reward myself for staring at the medium screen all week.” This widely shared tweet by journalist Delia Cai incisively captured the zeitgeist during the height of the pandemic in 2020. The many who turn to watching streaming video to recover from their hard work in front of the computer may be relaxing, but they are not regenerating their attention and ability to focus.

Intensely focused attention is not sustainable, nor should we want that. It is critical to recognize that as we shift between different modes of focus, regeneration is one of the most essential. Taking time away from intensity and immersion is in fact vital to being able to sustain our more engaged styles of focus. Every day we need to switch off entirely from information and digital engagement to regenerate.

Going for a stroll in nature, exercising, having a bath, reading fiction, carefully cooking a meal, meditating, lying on a couch daydreaming, playing an instrument, and extended sensual explorations with a partner are all ways that I and many others regenerate, taking us away from the aggressive submersion in information that is intrinsic to modern life. What are the activities that work best for you to regenerate yourself? If you wish to be as productive and effective as possible, these must be part of your daily schedule.

In fact, these kinds of activities put you in a state of mind that is highly conducive to synthesis and insight, when your very best ideas come to you. Constant busyness will let you achieve tasks, but it is when you pull back to see the big picture that you will identify opportunities and recognize where best to apply your efforts.

The Value of Information Routines

Most people begin their day by checking their emails and the news, “so I know the world didn’t break when I was asleep,” as Seth Godin put it,21 but don’t take that as an assumption on how you should work. We usually want to find out what’s going on in the world, but other than quickly confirming that the world is still intact, we can do this whenever best suits us.

Daniel Ek, founder and CEO of music-streaming giant Spotify, moves to the beat of his own drum. He says, “I wake up at around 6:30 in the morning and spend some time with my kids and wife. At 7:30, I go work out. At 8:30, I go for a walk—even in the winter. I’ve found this is often where I do my best thinking. At 9:30, I read for thirty minutes to an hour. Sometimes I read the news, but you’ll also find an ever-rotating stack of books in my office, next to my bed, on tables around the house. Books on history, leadership, biographies. It’s a pretty eclectic mix–much like my taste in music. Finally, my ‘work’ day really starts at 10:30.”22

Most of us tend to fairly consistent morning information activities. Fewer establish deliberate daily patterns for allocating their precious attention. Establishing methodical information habits is a huge opportunity.

Following thoughtfully designed information routines will dramatically enhance your effectiveness.

Planning when and for how long you engage in specific attention modes minimizes costly task-switching and ensures you are allocating time to the most valuable activities. The routines that will work best are unique to each of us; we need to discover them by trying.

Optimizing for Your Chronotype

One of the beguiling things about humans is that we are all different. Our states of mind and neurochemical balances consistently shift through the day, each with our own distinctive patterns. Knowing yourself well enough to select the best times of day for different activities is a superpower that can massively enhance your productivity and effectiveness.

Do you consider yourself to be a “morning person” or an “evening person”? Academics call this our chronotype, creating measures of what they describe as the “morningness” or “eveningness” of a person.23

One important implication is the best time for your Deep-diving sessions, which are far more likely to be productive if timed to coincide with your greatest cognitive capacity. Because of the basic rest-activity cycle and its differences between individuals, we also need to be aware of how our alertness varies through the day. Some people experience a slump after lunch or other meals, which can be diet-related, but which should shape how you allocate your time (and perhaps what you choose to eat).

Timeboxing Your Information Engagement

Business used to be slow, predictable, and comfortable (well, at least compared to today!). As the pace of change accelerated, software development began to shift from traditional project management techniques to a set of methodologies commonly called “agile,” allowing far faster development of usable software and improved responsiveness to changing requirements. One of the principles that supported agile development was “timeboxing,” which simply allocates a fixed period of time to work on a deliverable. This meant that if the planned functionality couldn’t be achieved in the time allocated, the scope was adjusted to include only the most important elements, forcing prioritization of features and work.

In 2004, blogger and author Steve Pavlina wrote a post modestly titled “Timeboxing.”24 He described how he had been inspired to apply the concept from software development to his personal time management. Pavlina concluded by writing that his wife had come home with dinner and a movie rental so that was the end of the post.

The idea of timeboxing for personal scheduling has gained substantial traction in recent years. Ardent advocates include both Bill Gates and Elon Musk, who divide their working days into segments dedicated to specific activities, not allowing them to bleed into successive timeboxes.

Nir Eyal, author of Indistractable, calls timeboxing “the nearest thing we have to productivity magic.”25 If you allocate time to working on a project, you can hold yourself accountable for whether you did that or were distracted by social media or other things. You can assess whether time you block out for being with your family or out in nature is being cut into by distractions. In exactly the same way, if you want and intend to spend time browsing Instagram or watching streaming shows, you can do that with a clear conscience simply by allocating that time in your calendar.

This is particularly important for those whose jobs mean there are constant demands on their time. LinkedIn’s Jeff Weiner blocks out in his calendar the thinking time he needs to do his job well. “In aggregate, I schedule between 90 minutes and two hours of these buffers every day (broken down into 30- to 90-minute blocks),” he shares. “It’s a system I developed over the last several years in response to a schedule that was becoming so jammed with back-to-back meetings that I had little time left to process what was going on around me or just think.”26

Billionaire PayPal cofounder Max Levchin reports, “I tend to come up with precise routines and repeat them obsessively every day. In perfect detail, every morning at home looks the same. By cutting out the contemplation of what to do next, I achieve extreme efficiencies.”27

Considerations in Setting Your Information Routine

You are unique, in ways that you understand and some that you have yet to discover. Generic prescriptions aren’t useful. You need to work out, to some extent by trial and error, what schedules for your attention modes will work best for you. As you develop your information routines, take into account these principles:

Don’t necessarily start the day with information. A staggering 80 percent of people say they check their smartphones within 10 minutes of waking.28 Don’t do this as a reflex; consider letting your thoughts flow freely for a while, as many highly successful people choose to do. Former Disney CEO Bob Iger says, “I create a firewall with technology, by the way, in that I try to exercise and think before I read. Because if I read, it throws me off, it’s distracting. I’m immediately thinking about usually someone else’s thoughts instead of my own. I like being alone with my own thoughts, and it gives me an opportunity to not just replenish but to organize, and it’s important.”29

Concentrate Scanning time. Many people begin the day wanting to find out if there was any major news overnight. This can be done by Scanning the headlines in a few minutes, though many people take the time to get their full “news fix” at this time. Unless you need continuous updates for your work, consider my precept of limiting update frequency. Do you really need to scan news headlines multiple times during the day?

Find time pockets for Assimilating. A key choice is whether you assimilate your articles when you find them, or park them to read later. Brian Stelter, the media correspondent of CNN and formerly the New York Times, reports that, “between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m., I start opening what ends up being dozens of browser tabs—links from Twitter, links from Facebook, stories in The Times, stories that Jamie sends—on my computer. My goal is to close all those by the end of the day. . . . I’ll at least skim all those open tabs by the end of the day.”30 Make sure that you allocate sufficient time to making sense of the content you have flagged so you can incorporate it into your thinking.

Block out Deep-diving. Deep-diving stands alone; by its nature it requires an extended period of focus. Even if you don’t use timeboxing at the center of your time management, be sure to block out time in your calendar for your highly focused sessions. It is the only way you can get sufficient depth, for this limited period shutting everything off and brooking no interruptions.

Use Exploring for fun breaks. Healthy information habits include regularly going beyond your usual sources. If your inclination when you are taking a brief break from highly focused work is to check social media feeds, instead try going on a little adventure to see what you can stumble upon that is both fascinating and different from your usual fare. It will be far more refreshing.

Schedule times for Regenerating. Our attention needs regular regeneration, and watching streaming shows doesn’t do the job. If you can, set a time each day for something that helps revitalize your mind, perhaps a walk in nature, playtime with your pet, or completing an adult coloring book. On weekends go on a hike or cycle or join your child on the playground. Do whatever you enjoy the most, knowing it also strongly supports pragmatic achievement.

Beyond Information Addiction

“Dost thou love life?” inquired Benjamin Franklin. “Then do not squander time, for that is the stuff life is made of.” Being alive is an incredible gift, offering us beauty in the moment and always incredible potential to work toward worthwhile outcomes. With all that we could do with our time, when we look back on our lives, might we wish we’d spent more time checking our social media feeds?

Many people accurately describe themselves as “news junkies,” not able to keep away from their regular fix of the latest updates. Living in a world in which we can instantly slake our craving for the new, most of us often find that temptation irresistible. Our pernicious addiction is exacerbated by almost every aspect of the modern world.

We need to acknowledge we are information addicts. There is no shame in it. This allows us to act on it, to work to control our addiction.

I certainly admit to being an addict, not adequately able to control my craving for the latest in news and my networks. It is built into who we are, so if you are not an information addict, you have singular self-control, well done! But if we admit the reality of it, we can undertake to improve our habits.

The path of Alcoholics Anonymous, helping alcoholics stay sober, is unfortunately not open to information addicts. We cannot forswear our addiction completely and remain part of modern society. We need to be able to engage with information without it becoming compulsive and taking over more of our lives than we wish. These are skills that we can learn, practice, and develop.

Techniques for Freedom and Choice

There are a range of techniques we can use to help us transcend our addiction and keep focused, to help us tend toward enabling information habits rather than ones that sap our time, energy, and life. Use any or all of the techniques in this section as you are inclined to gain control over information:

Minimize notifications. Do you really want to be a slave of a device that interrupts you with what are almost always trivialities? The single easiest and most powerful thing you can do to take control of your life and maintain focus is reduce to a minimum the overt notifications you receive. The first thing I do when I get a new phone or download a new app is switch off sound notifications. Set up your phone so that it only rings or notifies you of a text message if it is from someone you know you will want to answer immediately.

Manage expectations. If you reply immediately to messages, you are setting people up to expect that you will always do that. Scheduling specific times of day for messaging avoids constant task-switching and can substantially increase productivity. If your work requires frequent collaborative exchanges, make sure there are times when you can switch off, if necessary letting your colleagues know you won’t be available for those periods.

Become aware of your actions. The first step to transcending the lure of information distractions is to be aware of your actions. Try to notice when you pick up your phone or device. Don’t let it be a reflex action: if you find your phone in your hand, ask yourself why. What do you want to achieve? If it is just to check there haven’t been any critical messages, then do that and put it down. If it is to relieve your boredom or provide distraction from a challenging task, give yourself alternatives for what you could do instead.

Delay gratification. If you feel an impulse to check your email or social media or the latest news, acknowledge your desire, but tell yourself you will do it in 5 or 10 minutes. This gives you more focus time during which you might transcend your transient desire and exercise your attention muscles. As importantly, it demonstrates that you are not powerless in the face of your addiction; exerting control in this small way builds your capacity for choice over your information desires.

Substitute other activities. The desire for distraction can be sated in many ways. When I take a break from focus work at home, I try to pick up my guitar for a few minutes, do some breathing exercises, go for a brief walk outside, or read an interesting article on my reading list rather than check my phone for updates. Consider what would fulfill your brain’s hankering for a break without diving into the bottomless abyss of social media or news updates.

Limit time. If you sometimes want to reward yourself for a stretch of focus time by browsing updates, memes, or political gossip, indulge yourself. Before you start, simply decide how long is reasonable to spend on this before you resume focus work, and set your timer. Wallow and enjoy, then when your time is up switch your frame of mind back to the task at hand.

Get help from apps. Just as technology can lead us astray, it can also help us. There are myriad apps and tools that can assist us to block distractions, maintain focus, and transcend addiction. Have a look at the Resources for Thriving section at the end of the book for a list of tools to help improve your information habits.

Regularly switch off completely. The practice of “digital sabbaths,” eschewing technology or least email and social media for a day a week or selected weekends, is highly beneficial, helping reset your brain’s overly established patterns.

Strengthening Your Attention

An early study compared how Zen masters and untrained people respond to the world. Researchers used brain wave sensors to measure the subjects’ “startle response,” which indicates people’s reaction to unexpected stimuli.

When a metronome was started next to untrained people, for the first few ticks they showed a strong response that quickly subsided until the ticks of the metronome barely registered. This is completely natural. Our brains are geared to novelty and actively filter out what recurs consistently.

However, when the scientists tested Zen practitioners, they found an intriguing response. Just like the nontrained people, Zen masters were startled by the initial tick of the metronome. Then as the metronome continued ticking, their response remained almost the same as for the first tick, on and on.31

The Zen masters were not becoming habituated to repeated sensory impressions. Everything was fresh to them, even if they had experienced it before. They had trained their brain not to filter out the world around them, but to be constantly paying attention.

One of the reasons I moved to Japan in my late twenties was my longstanding fascination with Zen. I ended up living for a year in a Zen dojo while I worked as a financial journalist, meditating twice a day and performing chores for the community before and after my long train commutes to my work in central Tokyo. My Zen master, Nishijima-Sensei, taught me the path of full attention and how it can help us “distinguish the important from the trivial.”32

A highly distinctive characteristic of Zen meditation is that it is performed with eyes open facing a wall. Zen is not about shutting yourself off from the world. It is about “experiencing reality.” Zen practitioners are continually paying attention. If there is a fly buzzing around or disturbances, these are not to be ignored, they are merely noticed. I have found meditation invaluable not just in being able to focus and be more emotionally balanced, but also in heightening my perception of the world around me.

Meditation and Awareness

“Meditation has probably been the single most important reason for whatever success I’ve had,” proclaims Ray Dalio, billionaire founder of leading hedge fund Bridgewater and author of Principles.33 Other endorsements of the value of meditation come from scores of leaders, including the likes of Marc Benioff, founder of Salesforce, Padmasree Warrior, a director of Microsoft and Spotify, and author Yuval Noah Harari, who says, “Without the focus and clarity provided by this practice, I could not have written Sapiens and Homo Deus,” books that have together sold over 20 million copies.34

Despite the clear value, it would be fair to say that most people struggle with starting and continuing meditation. Not everyone wants to meditate, and that’s fine. However, hopefully what you read here will provide a further small nudge in that direction. I will provide some suggestions on starting meditation, as well as other practices to help control your attention. Any effort you put into it will be amply rewarded.

As author Daniel Goleman notes, “attention works much like a muscle—use it poorly and it can wither; work it well and it grows.”35 If we want to strengthen our body, we go to a gym regularly to exercise. We don’t need to kick off with an athlete’s regimen; we just get started and gradually build over time. In exactly the same way, if we want to strengthen our focus, we need to start deliberately exerting our attention, even in small ways, and in time make our practice consistent. There is no other way to improve.

There are dozens of different types of meditation. Practitioners of transcendental meditation repeat a mantra given to them by their teacher. Many forms of meditation including Vipassana start with a focus on your breath. Chakra meditators focus on the energy centers in their body. Body scan meditation draws attention to different parts of your body in turn.

What is common to all meditation is consistent attention. It is absolutely inevitable that our minds wander; it is the default condition of our brains. When meditators become aware that their minds are wandering, they gently draw their attention back to their chosen focus. Practice makes them more able to maintain their attention, so they wander less frequently and are more readily able to resume their concentration.

Steve Jobs meditated consistently through his life from age 19. “If you just sit and observe, you will see how restless your mind is,” he said. “If you try to calm it, it only makes it worse, but over time it does calm, and when it does, there’s room to hear more subtle things — that’s when your intuition starts to blossom and you start to see things more clearly and be in the present more. Your mind just slows down, and you see a tremendous expanse in the moment. You see so much more than you could see before.”36

How to Start to Meditate

If you already meditate consistently, congratulations! You not only understand the benefits, you are taking sustained action that will consistently improve your attentional capabilities. If you don’t meditate and have a glimmer of an inclination to try, follow these guidelines:

Begin with very short periods, but try to do it every day. Don’t be overambitious. Numerous studies have demonstrated substantial benefits of meditating for short periods, and your initial intent is to build a habit. Even if you feel exceptionally busy, you should be able to find 10 minutes to do something that will almost certainly increase your productivity. If that seems hard, start with five minutes. Only when you feel like it, gradually increase the duration to whatever period suits you. While longer meditation periods will have greater benefits, don’t believe anyone who suggests brief meditation sessions aren’t valuable.

Focus on your breathing. We all breathe, so it is easy to pay attention to our breathing, as many forms of meditation do. Focus on the in breath and the out breath; just be aware.

Try meditating with your eyes open. It is probably easier to meditate with eyes closed, as most traditions suggest, so do that if it works better for you. Personally, I prefer meditating with eyes open as it emphasizes that I am paying attention to the world, not shutting it off. It also allows me to expand my visual attention while I meditate, as we learned earlier.

Consider it practice in returning to your attention. You will inevitably get distracted and may end early meditation sessions feeling that you never had control of your attention. That is completely OK—it is a journey. Consider it a win when you notice that your mind is wandering and return your attention to your breath. Every time you become aware that your attention has flown the coop and you come back, you have strengthened your attentional muscles, giving you more control.

Set a time of day or cue. Choose an activity or event that will trigger when you meditate—for example, after a morning shower, before making dinner, or during a scheduled morning break. James Clear of Atomic Habits fame calls this “habit stacking,” making the activity automatic rather than something you need to decide to do.37

Enjoy it! It will be hard to meditate consistently if you consider it a chore. When you are paying full attention, with every breath you are living fully, experiencing yourself, your evanescent thoughts, and your environment. Savor the uncommon every-moment awareness. Also appreciate the difference you may feel after you meditate. You might find you start to grow hungry for this state of mind.

Awareness Practices

Whether or not you meditate, you can improve your attention control simply in how you go about your daily pursuits. In their book Mindfulness, Oxford University professor Mark Williams and journalist Danny Penman propose what they call “habit breaking,” each week choosing one daily ritual such as teeth brushing or taking a shower and each time giving full awareness to the experience.38 Instead of doing these activities automatically, without thinking, you exercise your attention.

Throughout each day you have opportunities to pay full attention. See what happens when you give absolute and full attention to someone when they are speaking to you. Every time you eat is a possibility to give your attention to the food you are consuming and relish its flavors. Whenever I’m waiting at a pedestrian crossing, I take it as a cue to stop thinking and focus on my breathing and what’s around me. These kinds of practices not only increase the richness of your life, but they also develop your ability to pay attention to what you choose, with powerful benefits in an information-saturated world.

Choosing the Power of Attention

The first step to choosing the power of attention is simply understanding that there are different modes that each have their place. Rather than flitting about through the day, strive to engage in consistent attention for extended periods. Enjoy the variety of exploring intriguing back alleys and taking the space to regenerate, as well as immersing in stretches of deeper focus.

Make the effort to consider and set enabling information routines, allocating time judiciously to the activities that benefit you the most. Attention is like a muscle that we can work to strengthen. Select among the many practices you have learned to develop your faculties.

In Chapter 5 we study how to expand our unique human capability of synthesis. This brings together and builds on facets of each of the other four powers, supported by our ability to adopt and move between attention modes.

EXERCISES

Your Information Routine

Record your initial thoughts on developing an enabling schedule for engaging with information. For each attention mode, write intended times of the day for this activity, the duration, and frequency (times per week, daily, or more frequently).

What will you do to embed these schedules and practices into your daily activities?

Practices for Strengthening Attention

What will you do to develop your capacity for attention? What practices will you undertake, and when in your daily routine?