HEARING

A Building Block to Talking

FOR YOUR CHILD to speak and communicate verbally, she needs a few things in place—like hearing. Hearing is one of the most important building blocks for effective oral communication. To most of us, it is absolutely effortless. Unlike talking, which develops over years through a series of changes, hearing begins to develop in the womb. It is part of an incredibly complex system that involves tiny bones and cells in the ear and neural pathways to the brain, and if your child’s auditory system is not working fully, many of her communication abilities can be compromised.

Difficulty hearing can have an impact on social interaction and academic performance in children. Good hearing brings about timely speech and language development—everything from mastering correct pronunciation to learning proper grammar to laying the groundwork for reading. Your child’s ability to hear can have a profound effect on his listening comprehension and his behavior. This includes being able to follow directions and pay attention to the teacher in school.

Parents have a lot to look out for in terms of kids’ hearing issues. According to the National Institutes of Health, between two and three kids of every 1,000 children are born either deaf or with a hearing loss. And hearing issues can lurk even when you do not expect them: More than 90 percent of deaf babies are born to hearing parents.

In addition, some kids develop hearing loss as they get older. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, two in every 100 children have experienced some sort of hearing loss. Children may get ear infections, suffer accidents, or lose some hearing as a result of a separate underlying health condition.

But the good news is that medical advances have made it far easier for parents to address their child’s hearing needs. We have more and better tools to detect hearing loss at even the earliest stages of life. And we have great methods to ensure that our babies and toddlers can truly hear us, even if it seems like they are always tuning us out. In addition, parents also have a range of corrective devices, therapies, and surgeries available to them.

In this chapter, we will help empower all parents to understand if their child suffers hearing loss—with the goal of making sure their kids are great communicators.

WHAT’S HEARING, ANYWAY?

Hearing, simply defined, is the ability to detect sound. Sound is the occurrence of vibration of air particles. For a person or a thing to make a sound, a particular event must occur, like using your vocal cords or plucking strings on a guitar. This, in turn, causes tiny air particles to vibrate. Sounds can be emitted at different frequencies, the rate at which vibration occurs over a period of time, depending on how big the vibrating object is. We interpret frequency as the highness or lowness of the sound, or pitch. For example, men’s vocal cords vibrate slower than women’s vocal cords because they are bigger, and men’s voices typically have a lower pitch in comparison to women’s voices.

The frequency of sound is measured in hertz (Hz). We can perceive sounds ranging from 20 Hz (very low frequency sounds like those made by a pipe organ) to 20,000 Hz (very high frequency sounds like the buzz from a mosquito). When we speak, we emit sounds that are high, middle, and low frequency—even in the space of one sentence. You might not realize it, but when you utter a few simple words like My name is Sarah, you are speaking in frequencies as low as 100 Hz and as high as 12,000 Hz. Your child needs to be able to perceive a variation of frequencies to adequately hear important differences in speech sounds.

The intensity of sound is measured in decibels (dB). Most people can hear very quiet sounds, like whispering, which tends to clock in at around 20 to 30 dB, and feel pain when hearing very loud sounds like a jackhammer, which is usually at about 130 to 140 dB. People who cannot hear sounds at 90 dB or greater are considered to have a profound hearing loss; in other words, they are considered to be deaf.

Hearing is different from listening, although the two words seem almost like twins. Listening refers to our ability to pay attention to and interpret sound. When our ears pay attention to and interpret the acoustic information around us—such as how loud or fast a vibration is—we can actually extract meaning from the sound. For example, we know when we hear a siren that an ambulance or a fire truck is nearby, or when a baby cries that she is hungry or distressed.

We use both of our ears to know the direction in which sound is coming from. This ability is called localization or directional hearing. Hearing loss in one ear can negatively affect that ability, especially in noisy environments like classrooms or playgrounds. Not knowing where sound is coming from can have a negative impact on listening and learning as kids can have trouble focusing on important acoustics (such as their teacher’s voice) and blocking out background noise.

Some kids can’t detect the range of frequencies that others can; other kids can’t perceive sound at quiet levels; and yet others can’t localize sound. Our ability to perceive sound and to give meaning to it are the essential ingredients for your child to gain the speech and language skills she will need.

WE LIVE IN a noisy world. We are exposed to noise all day long. Some of this noise is potentially harmful to your child’s hearing and, of course, your own. Later in this chapter, we’ll walk you through the physical damage that noise can do to your child’s ear. But before we get there, we want to introduce some facts about the world your child lives in and how modern technology may be harming your child in ways you may never have considered.

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), sounds that are louder than 85 decibels—such as a blow dryer, a kitchen blender, a lawn mower, or a nearby subway or bus—can cause permanent hearing loss. Noises that your child may be exposed to every day can all exceed this recommended level.

There are other sound demons that are probably right in your living room. Your TV can be well over 85 dB, too. Does your child ever use your phone or a tablet to watch cartoons or play games? Guess what? If the volume is on high and the device is close to your child’s ears, it may be exceeding ASHA’s recommended sound level. Some toy phones, music players, trucks, or talking dolls are also well above ASHA’s recommended level for noise. Kids like to put things close to their ears—so keep the noisy toys away. (See the Resources section at the end of this chapter for a guide to consult on toys to avoid.)

HOW DOES HEARING DEVELOPMENT HAPPEN?

Your baby’s ears start to form at about 3 weeks gestation, and some parts are fully formed when she hits the 20-week mark in the womb. By that time, babies can detect sound. Remember, your baby is floating in a big bath of water, so she can’t hear all the sounds that we hear every day, but certain aspects of sound, such as intonation and rhythm, are transmitted well to your baby’s ears.

While your baby is in utero, growing and getting bigger, he is listening to the sounds all around him—like the noise on the street or the music in your home, as well as to the language or languages that are being spoken around him.

Research over the past 30 years by scholars such as Patricia Kuhl, Anne Fernald, and Peter Jusczyk has shown that babies must be listening because they respond to human voices in utero. By the time babies are born, they show a preference for what pediatric specialists refer to as infant-directed speech—or in less fancy terms, baby talk—the sing-song talk that we tend to use when we speak to babies. They can also distinguish between different speech sounds, like p versus b, and can detect their mother’s voice over other female voices.

DR. MICHELLE’S TAKEAWAY

START TALKING to your baby in utero. He is listening to you! And when he’s finally in your arms, don’t stop talking. He’s listening even more!

LET’S LOOK AT THE ANATOMY AND

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE EAR

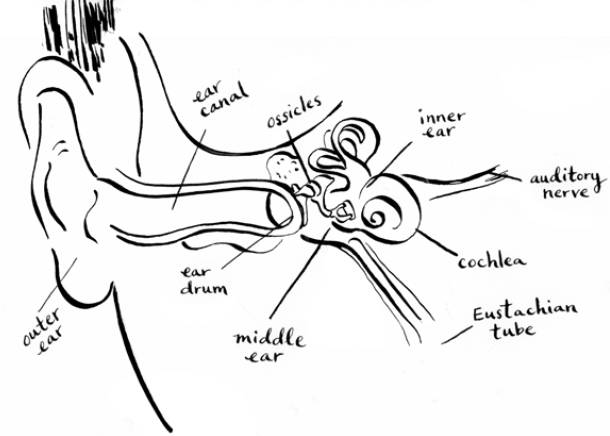

Look at your baby’s ears. They are so small. But they are so, so powerful. That tiny little ear has three main parts: the outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. Hearing is about the connection of these different parts of the ear, about the workings of the ear with the brain, and about how all these parts and pathways work together. Specialists refer to all of this as the auditory system, the sensory framework for hearing. The three parts of the ear join forces with pathways to the brain to make hearing happen.

THE OUTER EAR

The outer ear, which includes the part of the ear that is visible on a person, brings sound from the environment to the inner parts of the ear. It consists of the pinna, the floppy part on the outside of your head, and the ear canal, the narrow tubelike passage through which sound enters the internal part of the ear. The pinna collects and directs sound to the ear canal. Sound traveling through your ear canal makes your eardrum, the thin elastic membrane that separates the middle ear from the outer ear, vibrate.

THE MIDDLE EAR

The middle ear contains the three small bones, called ossicles, that attach to the eardrum. When the eardrum vibrates, these bones move and carry the sound vibrations. Our middle ear contains the opening to our Eustachian tube, which connects to the back of our throat and is responsible for equalizing ear pressure. When you travel in an airplane or drive up a large hill and your ears pop, your Eustachian tube is equalizing pressure. File away the words “Eustachian tube” for later, because they are really important in child-rearing—especially if your kid ever complains of an earache.

THE INNER EAR

The inner ear, which is involved in both hearing and balance, contains the cochlea, the sensory organ of hearing that is filled with fluid. The cochlea transmits sound energy to a neurological code. As the ossicles move, they set the fluid in the cochlea into motion. The cochlea is lined with tiny hair cells that bend in response to movement of the fluid. When the hair cells bend, an electrical impulse travels from the inner ear to the auditory nerve, the cranial nerve responsible for sensory information.

LAST STOP: THE BRAIN

From the auditory nerve, sound travels through the central auditory pathways, the nerve cells and fibers that connect the auditory nerve to our brain. The brain then figures out how to interpret these sounds, knowing that, perhaps, the loud sound outside means a car is honking or those words coming out of Mommy’s mouth are your cue that dinner is being served.

Figure 1-1 shows the auditory system.

Figure 1-1. Ear diagram.

HOW IS HEARING and speech perception related to speech production? Typically developing children learn speech through audition, the ability to hear and process sounds. Children have to hear speech sounds and detect meaningful differences in what they hear in order to say these sounds themselves. Children talk the way they hear, so if they are not hearing adequately, they will not say their speech sounds clearly. Researchers have also shown that early speech perception abilities are important for language development later on. Scholars such as April Benesish, Patricia Kuhl, and Janet Werker have shown a positive correlation between infant speech perception skills and language development in childhood.

TYPES OF HEARING LOSS

The ear is a very intricate organ, and both the ear itself and the auditory system in general can run into problems; many of these problems can lead to hearing loss. If you are concerned about your child’s hearing you should visit two specialists. Ear-nose-throat (ENT) doctors, also called otolaryngologists (but usually only by other doctors), are medical specialists in—guess what—ears, noses, and throats. ENTs can interpret hearing tests, perform surgery, and prescribe medication. Some ENTs further specialize in pediatrics. Audiologists are hearing specialists who have advanced university degrees in audiology (the study of hearing disorders), hold a license to practice in their state, and can evaluate and treat hearing, balance, and auditory disorders. Audiologists typically perform hearing tests and dispense hearing aids and often work either in practices with ENTs or in hospitals, clinics, or schools.

If you suspect your child may have one of the hearing impairments that we are about to discuss, then run, don’t walk, to your nearest ENT or audiologist. (Consult Chapter 8 for tips on finding good specialists.) Hearing loss can be a major contributor to speech and language delays, so the faster you can address your child’s hearing impairment, the faster you may be addressing his communication potential.

Young children can face hearing impairments for two reasons:

1.Babies can be born with hearing loss. This is called congenital hearing loss.

2.Young children can also suffer hearing loss after birth due to infections or environmental factors. This is called acquired hearing loss.

Specialists divide the universe of hearing loss into two broad categories:

1.Conductive hearing loss is caused by an abnormality in the outer or middle ear.

2.Sensorineural hearing loss is caused by damage in the inner ear—to the hair cells of the cochlea or the auditory nerve.

An individual can have both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss, which is called mixed hearing loss.

CONDUCTIVE HEARING LOSS

Conductive hearing loss occurs when the outer or middle ear is not working properly. A rip or hole in the eardrum, buildup of wax in the ear canal, or damage to the ossicles in the middle ear will not allow sound to travel to the inner ear. The most common cause of conductive hearing loss in children is fluid in the middle ear.

DR. MICHELLE’S TAKEAWAY

THE GOOD NEWS about conductive hearing loss is that most of the time it is reversible and can be corrected with surgery or medications.

Conductive hearing loss usually causes a certain degree of hearing difficulty, but not complete deafness. Children who experience it may have difficulty hearing quiet sounds, such as whispering, or medium sounds, such as conversational speech.

Ear Infections

Guys, this is the biggie. The single most common type of hearing loss experienced by children is caused by fluid in the middle ear, stemming from an infection. The technical term for ear infection is otitis media; if your child goes to the pediatrician complaining of an earache, you’re likely to come back home with the diagnosis of otitis media. Ear infections lead to a buildup of fluid in the middle ear, which in turn causes conductive hearing loss because the fluid doesn’t allow the bones in the ear to vibrate properly.

Ear infections are very common in children; according to the National Institutes of Health, five out of six children experience ear infections by the time they are three years old. Young children experience ear infections more frequently than older children or adults, because the Eustachian tubes in babies and young children are shorter and more horizontal. The Eustachian tube equalizes pressure in the middle ear and drains fluid. In adults, it is sloped downward, which allows fluid to drain easily. In babies, fluid is more likely to be trapped and remain in the middle ear. As a child grows, the Eustachian tube gradually becomes sloped and the child is less likely to experience ear infections.

Because ear infections tend to occur when toddlers are developing their speech and language skills, they are important for parents to pay attention to. For some children, having an ear infection can be like listening to the world with your hands over your ears. Academic research is conflicted about the long-term impact that ear infections have on speech and language development. But we know this: Adequate hearing is needed to develop speech. And ear infections accompanied by middle ear fluid result in hearing loss.

WHILE EAR INFECTIONS themselves don’t cause speech delays, even some hearing loss caused by fluid associated with ear infections can trigger a speech delay. Pediatricians are able to treat ear infections, but they do not typically monitor a child’s hearing. So if your child is only being treated for an ear infection and his hearing is not regularly monitored, he may be experiencing undiagnosed temporary hearing loss. Your child should visit an ENT if he experiences repeated ear infections or if you suspect hearing loss.

Ear infections come in many different shapes and sizes.

![]() ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

The “acute” in front of the otitis media means your child is in a lot of pain. Bacteria have infected the fluid in his ears. He is likely to experience symptoms including fever and ear pain that are caused by inflammation of the middle ear. He may be tugging on his ears a lot. Children ages 6 months to 24 months are most likely to experience acute otitis media, but preschoolers and early elementary school children can suffer from them, too.

Treatment for otitis media is typically a dose of antibiotics. Some pediatricians may watch and wait out the infection for several days before prescribing any medication.

Otitis media can also lead to a ruptured eardrum (rip or tear in the eardrum) caused by pressure created by the fluid in the middle ear. The eardrum usually heals within three months and typically no treatment is recommended. Another possible consequence of otitis media is cholesteatoma, which is a growth of skin cells in the middle ear. Cholesteatoma can grow large enough to cause damage to the ossicles. Treatment for this condition is surgery.

Otitis media with effusion refers to when there is a buildup of fluid in the middle ear that could become infected. When the fluid is thick and white, ENTs call the condition glue ear. All this fluid in the middle ear does not allow the ossicles to move properly, causing a conductive hearing loss that can range in severity from slight (meaning your child will have trouble hearing soft sounds like a whisper) to mild (she’ll have trouble hearing soft speech) or moderate (she will have trouble hearing conversational speech). If the fluid in your child’s ear is not infected, she will not receive antibiotics, and it can often take two to three months for fluid to drain completely and your child’s hearing to return to normal.

![]() RECURRENT ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

RECURRENT ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

Recurrent acute otitis media refers to multiple, separate episodes of ear infections over the course of several months. Some kids are more prone to ear infections than others, depending on the shape of their ears, noses, and sinuses. Dr. Michelle witnessed this condition in her own household: her first daughter, Annabel, suffered from several ear infections before she was three. Her younger daughter, Charlotte, had no ear infections before the age of three. Although the two girls look very similar, they have slight differences in their anatomy—not visible to the rest of us—that resulted in different symptoms from a common cold.

An ENT may recommend pressure equalization (PE) tubes, also called grommets, if a child has experienced multiple episodes of ear infections as well as allergy or sinus issues. These tubes are placed in the eardrum surgically and allow the pressure in the middle ear to equalize. This is a pretty simple surgery that typically occurs in an outpatient setting at a clinic or hospital. Sometimes, the tubes fall out and your doctor has to put in a new set if your child is continuing to suffer ear infections.

A relatively new device, called an EarPopper, can be used to open the Eustachian tube to equalize pressure so the fluid can drain.

![]() ACUTE EXTERNAL OTITIS

ACUTE EXTERNAL OTITIS

Acute external otitis, or swimmer’s ear, refers to an infection in the outer ear canal caused when bacteria grows in water that remains in the ear canal after swimming. The good news about swimmer’s ear is that it can usually be treated with eardrops.

PARENTING TIP

LOTS OF KIDS get ear infections; they are one of the most common reasons for visits to the pediatrician. But Dr. Michelle has a few ideas about how to prevent them:

•Don’t let your baby fall asleep drinking a bottle. The liquid can pool in her mouth, allowing it to enter the Eustachian tube.

•If you can, nurse your baby. Babies who are breast-fed are less likely to experience ear infections.

•Don’t smoke. Babies who are around cigarette smoke are more likely to have ear infections.

SENSORINEURAL HEARING LOSS

Sensorineural hearing loss is the result of damage to the inner ear hair cells or nerves that carry information to our brain. Unfortunately, sensorineural hearing loss is permanent. Once a person’s hair cells are damaged, there is no medication or surgery to repair them. However, there are some treatment options to help children hear better. Hearing aids amplify or make sound louder. Another treatment used for children with severe to profound hearing loss is a cochlear implant, a device surgically implanted in one’s cochlea, in the inner ear, that acts like hair cells by sending electrical impulses to the auditory nerve when sound enters the ear.

Children with severe sensorineural hearing loss usually learn to communicate verbally, but may also communicate in other ways, such as through American Sign Language.

Genetic Conditions

Babies born with sensorineural hearing loss typically have underlying genetic conditions. These babies may be deaf or may suffer from partial hearing loss. Remember that the vast majority of babies born deaf have hearing parents. If your baby was born with sensorineural hearing loss, you or your partner may have had an uncle or a distant cousin who was deaf. Or you may have been surprised: that’s because parents may be carriers of a recessive gene that causes hearing loss and will not necessarily anticipate a hearing problem in their baby. Waardenburg syndrome, a group of conditions passed down through families that may involve deafness as well as pale skin, hair, and eye color, has a dominant genetic pattern and can also cause sensorineural hearing loss at birth.

Infections and Ototoxic Drugs

Illnesses accompanied by very high fever, often stemming from bacterial meningitis, mumps, and measles, can cause sensorineural hearing loss. Also, medication used to treat these illnesses can damage hearing. These ototoxic drugs, which can cause damage to the hair cells of the inner ear, are often antibiotics that end in the suffix “-mycin,” such as neomycin or streptomycin.

PARENTING TIP

THERE ARE AVAILABLE vaccines for many of the illnesses that can cause high fever that in turn may lead to hearing loss. We strongly suggest having your child vaccinated.

NOISE-INDUCED HEARING LOSS

Have you ever felt that you can’t hear well after going to a concert or a loud bar? There’s a medical term for that: Excessive exposure to loud noise can cause noise-induced hearing loss. If you visited that noisy environment only occasionally, then your hearing loss is simply temporary and can return to normal. But if loud noise is present for long periods of time on a regular basis, then the hearing loss can be permanent. Children and babies are exposed to many noisy environments, and that level of noise is typically not limited by any regulatory body. There are lots of noisy environments that your child may experience, but one often overlooked is the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The medication, machines, and equipment needed to help sick babies can potentially damage your baby’s hearing. Babies who spend long periods of time in the NICU may not respond to loud noises and sounds the way other infants do.

PARENTING TIP

KEEP THE VOLUME down on your TV, radio, smartphone, and tablets. If you have to raise your voice to speak over the TV or music, even slightly, then it’s too loud.

Helping a Child with Sensorineural Hearing Loss

If your baby or child is diagnosed with sensorineural hearing loss, there are a few options to help them hear you. Today, there are many types of hearing aids that are quite powerful in making sound louder so that it can be heard. Hearing aids require no surgery, so they can be used with very small babies. Hearing aids can be very expensive—often totaling thousands of dollars—and they are not always covered by insurance. Different types of hearing aids abound; if you are in the process of selecting a hearing aid, consider the device’s battery life. Hearing aid batteries often need to be changed several times a week. Hearing aids that use rechargeable batteries may be a good choice for you.

Another treatment that is used with children who have significant hearing loss is a cochlear implant. Cochlear implants require surgical implantation of wires in the inner ear as well as an external device, and in the United States they can be implanted as early as 12 months after birth. Cochlear implants wipe out existing hair cells, so any residual hearing would be lost when the device is implanted, representing a risk for this treatment option especially for children who have some hearing. Cochlear implant technology has come a long way since it was first introduced. Today, most children with significant hearing loss who receive a cochlear implant are very successful oral communicators.

Parents of children with hearing aids or cochlear implants may also want their child to use a frequency modulation or FM device in their home and the school the child attends. This small piece of equipment, worn by an adult, transmits your voice directly to the child’s hearing aid, like a personal radio.

No matter what treatment you, and your audiologist, and ENT decide on, the earlier the treatment, the better. One thing to keep in mind is that hearing aids and cochlear implants are imperfect tools. If you wear glasses, your vision will be restored when you put them on; the same is not true for hearing aids and cochlear implants. They help people hear better, but they don’t restore hearing completely. Kids who use hearing aids and cochlear implants need to learn how to use them. Over time, they gradually improve their ability to discern different sounds and frequencies.

While kids with hearing aids and cochlear implants may learn to communicate verbally, they often, but not always, experience speech and language delays.

TESTING, TESTING, TESTING

Kids today are lucky. Audiologists have many different methods to test hearing in babies, toddlers, and kids. The development and popular spread of hearing tests over the past several decades is great news for kids (and their parents!) because more and earlier testing methods have led to earlier detection of hearing loss. Until relatively recently, a child’s hearing loss was usually detected when he was in preschool or early elementary school, well after the child showed delays in language, speech, social, or academic development. Research supports that the earlier a hearing loss is detected and treated, the better the child’s speech and language development and academic achievement later on.

Here’s the lay of the land on the different testing options.

NEWBORNS

Today, nearly all states require newborn hearing tests. All states have Early Hearing Detection and Intervention programs that give extra support for newborns who suffer hearing loss.

Newborn hearing testing typically takes place in the hospital where your child was born. If you are planning a home birth or your birth center does not provide hearing testing, your baby’s hearing can be tested in a pediatrician’s or audiologist’s office. Some kids are considered especially at-risk for hearing loss, including babies who are placed in the NICU.

Your baby can’t raise his hand when he hears a beep, so audiologists use a special way to test his hearing. This test uses a probe to send a sound into your baby’s ear. Audiologists measure the response of a baby’s hair cells, also called otoacoustic emissions. A healthy ear will send a sound back out, like an echo. In an ear with hearing loss, no sound will come back. Babies need to be still and quiet to pass this test, so the audiologist at the hospital may whisk away your baby when she is asleep in order to test her. She may even be tested while she is feeding, as long as she is quiet.

Another way to test hearing in infants, or those who are hard to test—such as children with autism—is by measuring a child’s auditory brainstem response (ABR). For this test, sensors placed on your baby’s head measure the auditory nerve and brain’s response to sound.

TODDLERS

A toddler’s hearing is not routinely checked by an audiologist or pediatrician. That’s where you come in. If you, another caregiver, or a medical professional suspects your child may have hearing loss—possibly because he seems to have a speech and language delay—then it’s time to visit the audiologist.

Toddlers are not good at sitting still but they can let us know that they can hear different noises through their behavior. Audiologists often use a testing method called visual reinforcement audiometry. For this test, which can be used with children as young as 6 months and up to 24 months, your toddler is taught to look at a toy after he hears sounds from a nearby speaker. Your child will hear a sound and see a fun-looking toy light up or move; he will then realize that hearing the sounds prompts the toy to light up, and he’ll keep searching for the sound to come—usually a beep or an instruction from the audiologist. Audiologists can measure how well the child can hear the sounds by observing the child’s behavior.

PRESCHOOLERS

Hearing in children three to five years old can be tested using play audiometry, in which the child listens for a sound or beep and then drops a block in a bucket, or adds a ring onto a ring stacker, when the beep is made.

At this age hearing screening is often performed as a part of your child’s annual well visit to the pediatrician’s office. If your child has not received a screening by the time he’s off to kindergarten, it’s time to talk to your pediatrician. You want to make sure your child can hear the teacher properly.

SCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN

Some elementary schools perform hearing tests for children, but this is hardly the gold standard, because some groups (like the U.S. Task Force on Preventive Services) don’t recommend routine hearing tests for school-age kids while other groups (like the American Academy of Pediatrics) do. If your child isn’t getting his hearing tested in school, you should ask your pediatrician or regular medical professional about routine testing.

DR. MICHELLE’S TAKEAWAY

YOU KNOW YOUR child best . . . If at any point you suspect she or he is experiencing a hearing loss or not acting as you would expect, schedule a hearing screening with an audiologist. A healthy baby’s hearing is typically tested once soon after birth—and then not again for at least another three years. That’s a long time.

RED FLAGS

What to Look Out For and When

Your child may be displaying signs that she’s not hearing properly. Here are some specific things to look out for.

![]() If your child is experiencing a speech or language delay. Fortunately for you, we wrote two chapters on speech and language development in this book. Please consult Chapters 2 and 3 for the age milestones for speech and language development. If your child isn’t meeting them, his hearing should be evaluated so call up an ENT or audiologist and ask for a hearing test.

If your child is experiencing a speech or language delay. Fortunately for you, we wrote two chapters on speech and language development in this book. Please consult Chapters 2 and 3 for the age milestones for speech and language development. If your child isn’t meeting them, his hearing should be evaluated so call up an ENT or audiologist and ask for a hearing test.

![]() If your baby is not responding to loud noises. Newborns sleep a lot, but when your baby is awake and alert, she should respond to loud noises like a siren or pots and pans clanging. Her response should include looking toward the sound, jerking her body, or even crying. If she’s not regularly responding to loud noises, then it may be time to get her hearing checked.

If your baby is not responding to loud noises. Newborns sleep a lot, but when your baby is awake and alert, she should respond to loud noises like a siren or pots and pans clanging. Her response should include looking toward the sound, jerking her body, or even crying. If she’s not regularly responding to loud noises, then it may be time to get her hearing checked.

![]() If your baby is pulling on his ears or if your older child is complaining of ear pain or jaw pain. He may have an ear infection. Go visit your pediatrician.

If your baby is pulling on his ears or if your older child is complaining of ear pain or jaw pain. He may have an ear infection. Go visit your pediatrician.

![]() If your child is suddenly asking What? or What did you say? This is a very common sign that your child may be experiencing temporary hearing loss due to an ear infection. As we mentioned previously, ear infections can cause a conductive hearing loss. It’s time to go to the pediatrician and get your child’s hearing checked.

If your child is suddenly asking What? or What did you say? This is a very common sign that your child may be experiencing temporary hearing loss due to an ear infection. As we mentioned previously, ear infections can cause a conductive hearing loss. It’s time to go to the pediatrician and get your child’s hearing checked.

![]() If your child is older than a year and is not responding to his name. It’s time to visit the audiologist. Babies who are 12 months old—and even younger—respond to their name when it is called. If your baby is not looking toward you or does not pause from her playtime when you call her name, you must discuss this with your pediatrician. Not responding to one’s name by 12 months can be a warning sign for hearing loss or for a developmental delay.

If your child is older than a year and is not responding to his name. It’s time to visit the audiologist. Babies who are 12 months old—and even younger—respond to their name when it is called. If your baby is not looking toward you or does not pause from her playtime when you call her name, you must discuss this with your pediatrician. Not responding to one’s name by 12 months can be a warning sign for hearing loss or for a developmental delay.

COMMON QUESTIONS,

EXPERT ANSWERS

Fortunately, Dr. Michelle is married to an audiologist, Dr. Mike. Over the years, they have answered hundreds of questions from parents about children’s hearing. Here are some common questions and their answers.

QUESTION: My daughter failed her newborn hearing test, and now we have to get a follow-up. Should I be worried?

ANSWER: Don’t freak out just yet. It is not uncommon for your baby to fail the newborn hearing test in the hospital. When your baby was born, she had fluid and mucus all over her body, including in her ears. It can take a few days for the ears to become clear, which can interfere with passing a hearing test. Babies born premature or diagnosed with a known genetic condition, like Down syndrome, are more likely to be born with hearing loss. Be sure to have a follow-up appointment scheduled within one or two weeks.

QUESTION: I’m sick of hearing Frozen for the sixteenth time, so I have made my daughter listen to the movie with headphones. Will this affect her hearing?

ANSWER: It can if the volume on the headphones is too loud. Repeated exposure to loud noises can cause noise-induced hearing loss, which is permanent. You child’s ears are smaller and usually more sensitive than your ears, so sounds that may be comfortable to you could be too loud for her. Consider setting the volume for your child at a level that sounds soft to you.

QUESTION: Will my child grow out of ear infections?

ANSWER: Yes. Ear infections occur most frequently in children under three years. Young children’s Eustachian tubes are more horizontal, so fluid can easily get trapped and infected when your child has a cold. Although older children and even adults can experience ear infections, they are much less common after age 8.

QUESTION: My child seems to tune me out when he is playing. Can he hear me?

ANSWER: Probably. When young children play, they can be very intense and seem to ignore you when they are concentrating on puzzles, art projects, or Legos—that’s normal. If your child doesn’t respond to you when she is looking at you or is not engrossed in an activity, it’s time to see your pediatrician and/or an audiologist.

QUESTION: My toddler doesn’t seem to hear me well and I see a lot of wax in his ear. Can I use a Q-tip to get it out?

ANSWER: Absolutely not; you need professional help. Earwax, also called cerumen, is important for protecting the ears: It traps and collects foreign objects such as dirt, debris, and bugs. Wax sits along your ear canal; at the end of the ear canal lies your eardrum. However, a large accumulation of earwax can create a blockage, causing temporary hearing loss. We know; you see all that gross wax in your child’s ear and want to get it out. But don’t reach for a Q-tip to get the wax out of your child’s ear: You are likely to push the wax in further, and because kids have shorter ear canals than adults, it is possible to rupture your child’s eardrum if you push the Q-tip too far. A wet washcloth is the best way to remove earwax that is visible. An audiologist or ENT can use a special medical instrument to extract the wax that’s really lodged in there. Don’t try it at home!

BEFORE YOUR CHILD trots off to school, you might want to think about the noise she will be exposed to in the classroom. Classrooms are noisy. Other students are talking (or, likely, screaming), air conditioners or fans hum and whirl, and hallway conversations compete with the teacher’s voice. There is often background noise from outside sources such as lawn mowers, construction work, and children playing at recess. These sounds can bounce off hard surfaces like walls, chairs, and desks and interfere with what the teacher is saying.

Noisy classrooms can negatively affect auditory comprehension, reading and spelling, concentration, and overall academic achievement in all children. Children with particular learning difficulties—such as kids who have hearing loss, attention difficulties, speech and language delays, and those whose first language is not English (or the language of instruction)—are particularly affected by noisy learning environments.

Dr. Mike suggests reducing the noise in classrooms:

•Install carpet, rugs, or foam tiles on the floor or part of the floor.

•Hang curtains or blinds on the window.

•Hang absorbent material on the walls, such as cork board or fabric (e.g., flags or student artwork, especially art that contains different textures).

•Place split tennis balls or felt pads under chair legs.

Work with your child’s teacher to reduce background noise. All children in the classroom will benefit, and so will the teacher. She will not have to talk louder to talk over the noise.

Marlowe’s Story

Marlowe was a strong and healthy infant, but she failed the newborn hearing test in the New York City hospital where she was born. The hospital’s staff audiologist and nurses assured Marlowe’s parents that she probably just had fluid in her ear, advising them to follow up with her pediatrician. Her parents took her to the pediatrician for more hearing tests several times over the next few months, but she never passed them. Nonetheless, Marlowe’s parents were certain she could hear; no one in any of Marlowe’s extended family had hearing loss. “We were in denial,” Marlowe’s dad recalls.

However, after two auditory brainstem response tests, it was clear: Marlowe had severe hearing loss in one ear and moderate-to-severe loss in another. Genetic tests didn’t turn up a clear reason. Her hearing loss was simply a mystery.

The family decided to try hearing aids for Marlowe when she was 4 months old. The result: She was transformed. “I was not prepared for the stark difference,” her dad says. “She was finally turning her head to our voices. She was a different kid.” When the family dog stirred in a nearby room, Marlowe would look up; she could finally hear his footsteps. Life with hearing aids wasn’t always easy, of course: Marlowe would try to take them off (her dad used tape to keep them on), and her parents worried that even with the hearing aids, she would not develop the proper verbal skills to communicate in a hearing world.

Soon thereafter, Marlowe began receiving speech therapy several times a week at home, and when she turned 2 she attended a nursery school for kids with hearing impairment. “When Marlowe went in, she wouldn’t speak, and when she left she wouldn’t shut up,” her father says. “They turned on that part of her brain.” Marlowe now attends a mainstream classroom at a local elementary school, where she continues to receive group speech therapy services. She is reading on grade level, socializes with her friends, and talks like a champ.

SOME SIMPLE THINGS TO DO AT HOME

Parents can do a little bit to help protect their child from hearing loss. As we’ve said before, we live in a very noisy world—one that’s getting even noisier with the prevalence of high-tech gadgets in our lives. So here are Dr. Mike and Dr. Michelle’s tips to keep things quiet on the home front:

![]() Put duct tape over the speakers of your child’s noise-producing toys to reduce loudness.

Put duct tape over the speakers of your child’s noise-producing toys to reduce loudness.

![]() Keep the TV, radio, or computer at a volume level low enough to avoid having to raise your voice to speak over it.

Keep the TV, radio, or computer at a volume level low enough to avoid having to raise your voice to speak over it.

![]() Buy earplugs or protective headphones (they look like ear muffs) for your child. We know—you might not see a lot of kids wearing them. But once upon a time, seat belts and bike helmets weren’t trendy either. We think hearing should be the next child safety concern. Consider earplugs or protective headphones in noisy environments like at parades, concerts, wedding receptions, or on noisy bus or train rides.

Buy earplugs or protective headphones (they look like ear muffs) for your child. We know—you might not see a lot of kids wearing them. But once upon a time, seat belts and bike helmets weren’t trendy either. We think hearing should be the next child safety concern. Consider earplugs or protective headphones in noisy environments like at parades, concerts, wedding receptions, or on noisy bus or train rides.

![]() Download a free—or really cheap—app to measure decibel levels in the environment around you.

Download a free—or really cheap—app to measure decibel levels in the environment around you.

RESOURCES

There is a wealth of information about kids’ hearing available online, from sites that focus on hearing impairments and disorders to sites that help you find ways to protect your child’s hearing. Here are some favorites according to Dr. Michelle and Dr. Mike:

![]() The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates hearing aids as medical devices, publishes a guide about different hearing aid options and how to choose the best one for your child’s needs: http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/homehealthandconsumer/consumerproducts/hearingaids/default.htm.

The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates hearing aids as medical devices, publishes a guide about different hearing aid options and how to choose the best one for your child’s needs: http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/homehealthandconsumer/consumerproducts/hearingaids/default.htm.

![]() The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has a lot of information about hearing development and disorders: http://www.asha.org/public/.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has a lot of information about hearing development and disorders: http://www.asha.org/public/.

![]() The American Academy of Audiology, a professional group for audiologists, hosts a website that helps parents learn more about hearing loss and find specific information on corrective devices, such as hearing aids. It also contains a link to finding an audiologist: http://www.howsyourhearing.org/index.html.

The American Academy of Audiology, a professional group for audiologists, hosts a website that helps parents learn more about hearing loss and find specific information on corrective devices, such as hearing aids. It also contains a link to finding an audiologist: http://www.howsyourhearing.org/index.html.

![]() The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is another source of information about hearing loss in children: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/hearingproblemsinchildren.html.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is another source of information about hearing loss in children: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/hearingproblemsinchildren.html.

![]() The Sight and Hearing Association publishes a yearly report in November of the noisiest toys and provides the loudness levels of these toys: http://www.sightandhearing.org.

The Sight and Hearing Association publishes a yearly report in November of the noisiest toys and provides the loudness levels of these toys: http://www.sightandhearing.org.