FREE SAMPLE CHAPTER FROM

STRESS-FREE DISCIPLINE

We hope you enjoy this sample from Stress-Free Discipline. Every parent struggles with a child’s behavior at some point, frustrated in figuring out what to do. Advice is everywhere, but little of it helps you to deal with your child at that moment. From bedtime battles to bad attitudes, Stress-Free Discipline allows you to pick the best strategy for specific situations with specific kids, based on their age, temperament, and issue. Role modeling, communication, ignoring, positive reinforcement, negative consequences, and more will expand your discipline toolkit and help you to nip challenging behaviors in the bud.

1

Decode Your Child’s Behavior

A parent’s job is never easy, or over! Discipline may seem an insurmountable challenge. That’s especially true if you’re reading this book in reaction to your child’s continued bad behavior, which has finally pushed you, or your partner, to a breaking point. But starting now, we want you to clear your mind of those troubles. We know it’s hard, but you’re going to start new with a blank slate and a fresh outlook.

You’re probably wondering, “Okay, Dr. Pete and Sara—how exactly do we do that?”

First, understand that parenting is not simply black and white, right or wrong. There’s no set of rules that say we all have to do things the same way. You’ll find you’ve made mistakes, like all of us do, but don’t let them make you feel paralyzed, or guilty, or inadequate. This is a learning curve for you and your child, and you’re both more resilient than you may think.

Second, we want you to know these two essential truths about child behavior:

1.Most of what you’re seeing is probably just normal behavior for a child.

2.It may feel like it sometimes, but your children are not intentionally trying to drive you crazy.

Sometimes, driving you crazy is just a by-product of their learning. Take a deep breath in . . . and out.

Knowledge is always a great de-stressor, because it more fully informs your decision making and reactions, which for so many of us is where that angst lives. That’s never as true as in parenting. Learning how something works is necessary to be able to correct problems when they arise, as well as to prevent them before they arise.

Understanding the normal functioning of a child’s mind helps us recognize when something really is wrong, as opposed to the typical challenges that we should expect. Child behavior involves an awful lot of trial and error. You can’t freak out if something happens just a few times. It may simply be your child testing his or her boundaries, trying to find the right behavioral path in a world where things are not always predictable.

In this chapter, we take you through normal childhood behaviors. We also help you develop an awareness of the kinds of influences that lead to both good and bad behaviors. Additionally, we explain how you can understand your child’s motives, and examine behavior as communication. You’ll learn to decode your child’s behavior in order to figure out how to shape it.

Knowledge is always a great de-stressor.

Most Problem Behavior Is Normal

What exactly is normal child behavior? Normal is a very broad term when applied to child behavior. The fact is that most kids, by definition, are normal, which means that most child behavior is normal, or at least explainable—even the stuff parents don’t like. Remember that our definition of discipline is education. This book will help you take those behaviors that are normal, but undesirable, and shape them into the kinds of behaviors you want to encourage.

Most behaviors that we consider inappropriate are simply part of child development.

Many behaviors that we consider inappropriate are simply part of child development. Take tantrums, for example. Little kids have tantrums sometimes as a method by which to express frustration, and they may hit or kick others as an attempt to get their way or may say things out of anger that are very hurtful. These are actually developmentally appropriate behaviors for children and are a part of growing up. Kids don’t yet know all the rules, and they don’t yet understand how their behavior may affect others. They test limits and boundaries (and parents’ patience) as a natural part of the development process. Children are learning how far is too far and what reactions they can trigger, while simultaneously trying to satisfy their needs and wants and learning to express emotions in an acceptable manner.

That’s not to say that you allow the hitting, kicking, or mean language to go unchecked, but even if some of these behaviors are repeated, please be reassured this is normal behavior. None of this reflects on your child’s innate goodness or your ability to be a good parent. If you can keep that perspective, you’ll do wonders for your stress level! (But if you are experiencing severe behavioral issues that you believe may go beyond normal and beyond your ability to manage or understand them, in Chapter 11 we discuss what goes into deciding to seek professional help.)

You can affect behavior by controlling antecedents and using consequences.

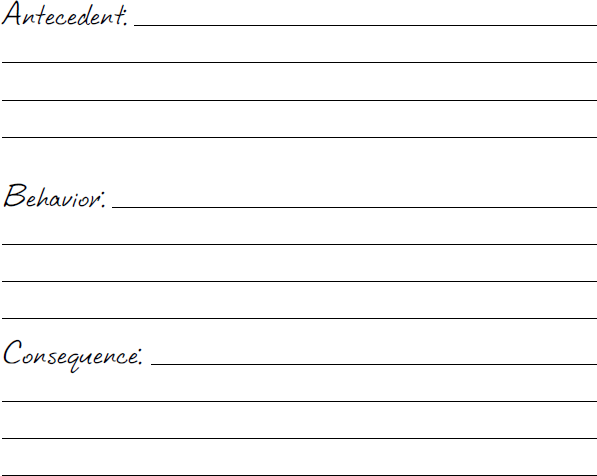

Before you can shape behavior, you need to understand behavior in general. When psychologists analyze a behavior, they think in terms of the ABC formula for behavior management: Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence. While this may seem a little technical, stick with us because throughout this book we will show you how you can affect behavior by controlling antecedents and using consequences in a wide variety of ways. First, though, we need to go through these terms and have a common vocabulary.

For our purposes, the antecedent is the buildup of events, the contributing factors, and sometimes the triggers that lead to the child’s behavior. The behavior is the response the child has in reaction to it. The consequence is what happens after the behavior that makes it more or less likely the behavior will occur again. A parent’s reaction to the child after the behavior can be one powerful consequence, as can punishments. However, there are many other potential consequences (intended and not) that can influence whether the behavior is repeated.

All behavior, positive and negative, follows the ABC pattern. The situations of each component are what vary widely, from person to person and circumstance to circumstance. Children are still learning the most basic of appropriate responses to the world that touches them, so they very often have to learn by watching your reactions, or by trial and error.

The clues to your child’s motivations for his behavior, and ultimately the prudent actions that you can take, lie within the context of this formula. These are the keys to unlocking your family’s stress-free discipline plan.

In its most simplified form, parents should reflect on ABC by asking two questions in the context of a particular situation:

1.Did the events that happened before the behavior make it more likely or less likely that my child would behave in a manner that I did not want? (Antecedent)

2.Did what happened after the behavior make it more likely or less likely that my child will exhibit that behavior in the future? (Consequence)

At first, asking yourself these questions may feel unnatural or unwieldy to consider during the heat of the moment. But as you reflect afterward, you’ll likely start seeing patterns of behavior in your child, and will be able to help shape his or her behavior in more effective ways. Eventually, asking yourself these questions will become second nature, but it’s also possible you’ll have fewer of those moments with which to contend.

Here’s an example of the ABCs of child behavior as seen from three simple scenarios that each begin the same way.

Scenario One: Mya is happily playing with a friend in the playroom. The two have been getting along pretty well for an hour when all of a sudden Mya grabs a toy away from her friend. The friend screams in indignation, and Mom intervenes and makes Mya give the toy back.

Antecedent: There are two girls playing for an hour, and one toy in particular seems to be most popular with them both.

Behavior: Mya grabs the toy away.

Consequence: The parent intervenes, and Mya has to give the toy back. Mya learns that she’ll have to give something back if she grabs it away, which makes it less likely that she’ll repeat this behavior.

Scenario Two: Let’s look at the same situation with a little twist. After Mya grabs the toy, what if the other child whimpers but doesn’t react in any larger way and the parents don’t notice the tiff?

Antecedent: Still the same.

Behavior: Still the same.

Consequence: Mya learns that grabbing gets her what she wants, which reinforces her behavior and makes it more likely she’s going to do it again.

Scenario Three: Here’s another twist: The children are playing and Mya’s mother says, “Mya, you’re doing such a great job sharing with your friend. High five, sweetie!”

Behavior: The toys are shared! The grab never happens because the parent has just reinforced the idea of sharing in Mya’s mind.

Consequence: Mya learns that she gets praise from her mom when she shares, which makes it more likely that she’ll share again at the next playdate.

As we said, these are very simple scenarios, and we all know that praising your child once won’t teach her to share. These three examples were aimed at giving you an obvious blueprint to the ABCs of behavior so you can identify each point in the cycle and see where you can start to shape behavior. There are a great many nuanced tactics that go into shaping behavior, and we take you through them for the most common stress points in the next few chapters.

Because parents can control antecedents and consequences to some extent, those are primary methods of dealing with behavior. A lot of the work of parenting involves manipulating A and C in order to impact B.

Most of us understand the concept that if we give our child a consequence, we can manage behavior. Punish bad behavior to make it stop. (So you know, punishments don’t always work, and, if they do, they often have merely short-term benefits; but more on this in the Universal Strategies in Chapter 2.) We’ve all used that word consequences countless times with our kids, and probably we heard it ourselves ad nauseam growing up:

“Be careful, or you’ll have to face the consequences!”

“Listen up, or there will be consequences!”

But let’s turn that on its end: Consequences do not simply consist of punishments. Praise is also a consequence. In fact, anything that happens after a behavior that impacts the likelihood of the behavior occurring again is considered a consequence.

Think back to the most recent behavioral issue in your family. Can you identify the antecedent, behavior, and consequence?

How could you have reframed this situation to positively affect your child’s behavior? Could you have avoided some of the contributing factors or triggers that served as antecedents? What if you chose a different consequence? Would that have made it more or less likely the behavior will repeat? Try making these changes the next time this situation crops up.

Antecedent: Jake and his dad take a boys’ day to go to a baseball game. It’s a last-minute treat because someone in Dad’s office had two tickets he couldn’t use. They’d been meaning to go all season but just hadn’t got there until today.

Behavior: After they get home from the game, Jake’s dad starts doing a few chores to get ready for the next day. As he’s taking out the trash, he sees Jake come in and start to help by sorting the recyclables into the right bins and then dragging the bins out to the curb, where he sees his dad put them each week.

Consequence: Jake’s dad thanks him for helping, and then later in the kitchen Jake overhears him bragging to his mom about how nice and responsible Jake was in helping. Jake loves feeling responsible, and was proud when he heard his dad saying such nice things about him to his mom. This makes it more likely that he will repeat the helpful behavior in the future. Jake’s mom and dad realize that more one-on-one time is likely to promote positive behavior and that sincere praise and acknowledgment further encourage that type of behavior.

We’re going to take a more nuanced look at the concept of punishing bad behavior and praising good behavior as we go through this book. Consequences can be highly effective, and since it’s what most of us currently use, we go through the concept in more detail in Chapter 2. Often, we parents fall back on negative consequences when we find ourselves in uncharted territory, discipline-wise, and that’s okay. Sometimes it’s most appropriate. Sometimes it gets your child’s attention more quickly.

Positive reinforcements and negative consequences are a powerful combination.

But giving a negative consequence is just the beginning, and it shouldn’t be your only tool. If it has been thus far, that may be the cause of some of your parental frustration. Avoiding problematic triggers, interrupting contributing factors, and using praise can shape your child’s behavior just as effectively as using a negative consequence. Taken together, positive reinforcements and negative consequences are a powerful combination of parenting tools.

Know this: Your child may not even be making a choice when it comes to bad behaviors. We adults think about choosing our actions, but our children may not yet be at that stage developmentally where any behavior is truly a conscious choice. Often, they are just acting on impulse, some more so than others.

Keeping vigilant about the contributing factors that lead to an undesirable behavior may sometimes be more effective (not to mention avoiding the combat that sometimes goes hand-in-hand with negative consequences). For example, by paying attention to the trigger in a number of meltdowns, you may start to see a pattern: that your child is not likely to follow directions well when she’s tired and grumpy.

It seems pretty obvious as you read that paragraph, right? Often, again in the heat of the moment, it’s easy to overlook the realities of hunger and tiredness as connected to bad behavior. We just see a child who isn’t following directions. But when fewer or simpler directions are given to a tired and grumpy kid, we see fewer problems. Save the other directions until he or she is alert and awake, and in this instance use the tools of redirection and coaching, which we discuss in Chapter 2.

The antecedent stage, once you can spot how it links to behavior, is one of the easier places to intervene and solve a problem before it happens.

Develop Awareness of Influences That Lead to Bad (and Good) Behavior

When you think about those factors that lead up to your child’s behavior, keep in mind that there are an infinite number of conditions or influences that can contribute to them. These include temperament, expectations of behavior for your child’s age, physical state, emotional state, as well as how he perceives himself.

It’s important to remember that both short-term antecedents (those that happen immediately before the behavior) as well as long-term antecedents (those that happened at some point in the not-so-recent past) can lead to a behavior. Like adults, children can nurse a grudge or dredge up long-forgotten conflicts from the past, which can influence problem behavior today. Some of our own reasons for taking action may go back years in time; others may have been caused by an annoyance from a few moments before that put us in a bad mood. It’s impossible to know everything that causes a behavior.

However, when looking at child behavior from the eyes of a parent, there are ways to target those contributing factors that have the most influence on an undesirable behavior. As a parent, you likely do this unconsciously, by knowing your child and using your instincts.

In order to truly utilize Stress-Free Discipline, we ask you to become more aware of these influences and how they affect your parenting approach. These influences can be both positive and negative, in terms of spurring behavior. We’ve broken them down into three broad categories, with examples, to help you connect them to your specific family challenges: situational influences, internal influences, and parental influences. All are ingredients in the soup that is behavior.

Situational Influences

Situational influences are circumstances that are actually happening at the time of the behavior. From causing an impulsive action to inhibiting a child from doing something, situational influences are “in the moment.”

•Temptation. The availability of something your child wants but that you’ve restricted, such as a plate of cookies within reach on a counter, as opposed to the plate being up high where she can’t access it.

•People. Individuals nearby can affect behavior, such as an authority figure who inhibits bad behavior, or friends who laugh and inadvertently reinforce silly or disruptive behavior.

•Activities. Lots of activities, or new activities, can mean competition for the child’s attention, providing more potential reasons to ignore a parent’s directive.

Internal Influences

Internal influences are those that stem from your child’s thoughts and innate disposition. They may include forces of which you are unaware. Many of them are far less controllable than other influences (for example, you can’t change temperament), but these factors should still be considered as you make your parenting decisions.

•Temperament. The child’s innate characteristics that are forming his or her personality, such as how a competitive child argues a point further than one who is sensitive, and a risk-taker is more likely to push behavioral limits to the max.

•Development. Cognitive, physical, and emotional maturity can affect behavior, as when the child with greater self-esteem may be able to better understand her own motives or consequences and behave accordingly.

•Knowledge. What the child understands about the situation, such as the child who is used to getting in trouble and no longer responds to negative consequences, or the child in an unfamiliar setting who can’t reason out the rules without explicit directions.

Parental Influences

Finally, we arrive at the type of influences on your child’s behavior that stem from you. Moms and dads, we have all been there. Stressed out, had a bad day at work, got caught in traffic, you name it—there are many things that can compete with your attention and influence your child’s behavior, as well as your reaction to that behavior. When your resources are reduced, you may not have the ability to pay attention to the factors that lead up to your child behaving badly.

•Temperament. You have your own temperament, or core personality (think Type A or Type B), that hardwires your responses to things like stress or problematic situations, which in turn affect your child’s behavior.

•Activities. As with your children, the types and number of activities you take on in any given day can induce a wide variety of behaviors.

•Support Level. There are times when the level of support from a co-parent, spouse, or extended family changes, and this may affect the way you parent.

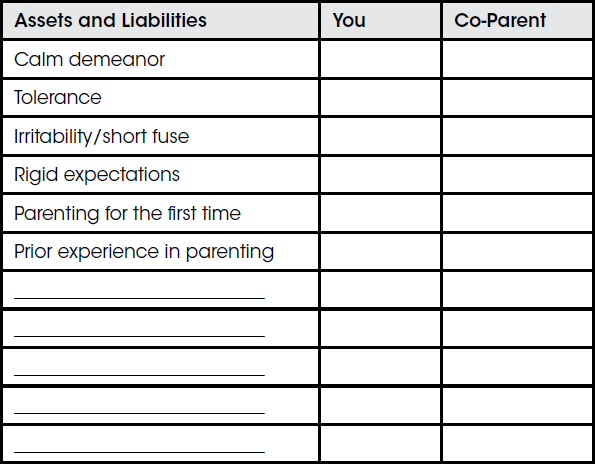

Chart Your Assets and Liabilities

Put a checkmark next to the asset or liability that describes you, and ask your spouse or co-parent to do the same. Then, add other assets or liabilities you see each of you possess at the end of the chart.

Finally, ask, “How does your partner respond to your weaknesses?,” and answer by circling one of the following:

IRRITATED DISMISSIVE NEUTRAL SUPPORTIVE

TOTALLY IN SYNCH

Use this chart to start a conversation with your spouse or co-parent and get on the same page in terms of your reactions to your child’s attitude behaviors. As co-parents, you want to play to each other’s strengths and minimize each other’s weaknesses. Consistency and persistence are what will yield behavior improvements in your child.

Understand Your Child’s Motives

“But,” you ask, “how can you be so sure my kids aren’t intentionally trying to drive me crazy?”

Not knowing your particular child or children, we can’t be 100 percent positive, but knowing our own and many thousands of others makes us pretty sure they’re just trying to find their way. Driving you crazy might be an entertaining fringe benefit, but it’s not usually their main goal.

But what exactly is their main goal? They want what they want when they want it.

What follows are some generalizations about different age ranges, but they’re commonalities that are true for most children.

Ages 3 and 4

In this age range, most children are self-centered. They feel like the world revolves around them. No one else matters except to help them get what they want, like a toy, a piece of food, or a destination. They want to get it, or get there. And that’s developmentally appropriate—it’s natural.

This is the core of why little kids don’t share. They don’t know they should, and they don’t see any benefit to it. They haven’t learned about perspective or empathy—that other people have feelings that should be considered. Part of the education (discipline) process for kids is to be guided by parents in developing these skills.

When you think of motives in children of this age, remember to keep perspective and focus on your child’s actions. As an example, at the playground, your 3-year-old daughter grabs the swing away from another child. When it’s pulled away, the other child loses his balance and falls down. She isn’t intentionally trying to hurt the other child; she just sees something she wants and acts accordingly.

Focus on your child’s action of grabbing the swing away, not necessarily on the fact that she hurt the other child. Explain how her actions affect others: “Use your words when you want something. If you’d talked with that boy instead of grabbing, you could have asked for the next turn and he wouldn’t have gotten hurt. Let’s go say ‘sorry.’” Keeping your child’s motivations in the forefront of your mind will help you with appropriate responses.

Ages 5 Through 7

In the 5-through-7 age range, goals shift a little. Children in this age range are starting elementary school and beginning to understand there are others around them. They’re trying to figure out how they can leverage relationships to get preferred treatment—testing boundaries of how they’re able to assert themselves, seeing how much advantage they can get in a certain situation.

Again, this is developmentally normal behavior, and frankly this is a trait to be prized. Balancing leverage is an important skill for successful adults. It’s okay for children to be selfish at this age, but they should be learning how to consider those around them.

Also at this age, children are learning the value of intangible goals, such as achievement. They’re looking to overcome a challenge and, in the case of the more competitive children, they’re looking to achieve something faster, higher, or better than another child. The competitive side of things can get quite intense at this age. One thing they often compete for, which is crucial for you to understand if you have more than one child, is your attention.

A common refrain you’ll hear is a claim of fairness. In some ways, this idea stems off as a variant of competition. Of course, the child’s sense of fairness is usually skewed in his or her own favor. While something is “equitable” from the parent’s perspective, it’s almost never fair from the child’s perspective.

Ages 8 Through 11

In the following few years, from ages 8 through 11, children begin to hone their persuasion skills, and their motivations may skew toward convincing you that they are right or that they should have what they want. (This, by the way, continues through adolescence and sometimes well into adulthood.) Again, this is perfectly natural, and a further extension away from egocentrism to perspective, but they are still refining the technique.

The child who learns to argue well to get what he wants is, in a way, learning to express the same sentiment as the one yanking the swing away from the other kid at the playground. Asserting their sense of self, children see themselves as having influence in the world, having power for the first time. They want to be important, and a way to do that is to manipulate or persuade others to their point of view.

Behavior = Communication

Rather than finding a specific motive to explain your child’s behavior, you should consider the idea that from the toddler to the preteen years, behavior is often a means of communication. For example, for a child who gets frustrated and acts out may have no other motive than simply expressing frustration. She might not have any words she can use to express this feeling within herself adequately, so, instead, the behavior erupts to help release the emotion. This is no different from the off-color words that might escape our lips when we, say, crack the screen on our phone, find the dog got into the trash, or get cut off in traffic.

Expressing negative emotions through behavior is common. A child stamps her feet or slams the door; she’s saying she’s mad. Another child bursts into tears, rubs his eyes, and puts his head down; he’s trying to say that he’s tired, but he may not even know or admit it.

There’s something cathartic about exploding that feels better than saying, “You know, Mom, the cookies are right there on the counter, and there seem to be plenty. I’m frustrated that you say I can’t eat any of them right now.” The refrain we’ve all heard and have likely said—“Use your words”—isn’t always possible, and certainly doesn’t feel as good. That’s not to say we disagree with it, but simply to remind you that your children are also human beings, and human beings do explode from time to time.

Children can communicate exuberance or excitement through behavior as well, expressing even positive emotions through bad behavior. A super-giddy girl may spin throughout the house, her arms extended straight out, forgetting her parents’ admonishments to watch out for that expensive vase on the counter until she hears it crash to the floor. In this case, unintended bad behavior was brought on by a positive motivation (happiness) she was trying to communicate through action.

When thinking about your child’s motives, remember not to overcomplicate things. If your young child hits another child in response to being bumped, there may not be any real motive behind that action. The behavior may have looked “mean,” but the intent was nothing more than impulsive retaliation. If it happens at school, however, he’ll be in trouble whether the intent was there or not. Because older kids who hit often do it to be mean, we might assume the young child has the same intent. Try not to assume motivations. What we’re trying to do is provide discipline (education) that helps our children change the way they deal with deep emotions away from behavior and into more appropriate methods of expression, like talking with a person about a problem.

Discipline (education) helps our children change the way they deal with deep emotions.

With older children, motivation increases in stages, so while a 5-year-old may not have sophisticated motives behind hitting another, an 8-year-old may have more so. And a 10-year-old certainly has more.

This relates back to the idea of behavior as a choice. As adults, we’re expected to be accountable for the choices we make. That’s not to say that children shouldn’t also be accountable. But children are often making far less informed choices than adults because they can’t consider all of the factors or options available to them. They aren’t capable of complex judgment in behavioral situations, so their motives can’t be considered in the same vein as ours.

It’s an important part of parenting and the establishment of discipline (education) to teach children to consider these various factors and consequences of behavior. Often, it’s hard to remember how impulsive children are and that their motive for doing something may simply be “because it was there.”

Just as essential, we parents must respect that our children are becoming people in their own right. They aren’t our malleable little babies any longer, and we need to respect each child as an individual. That means that we try our hardest to understand their influences, motivations, and temperament so that we can decode their behavior and address it effectively. We protect our children as much as we can, but we allow them to make mistakes so they can learn from them. We encourage them to be considerate of us as actual people, too (instead of simply food providers or trash receptacles; right, moms?). When they can start doing that, they can have empathy for their siblings, friends, teachers, and classmates. Eventually, as they mature into the strong, healthy adults we’re working so hard to produce, that empathy will extend to coworkers, neighbors, spouses, and their own children.

Helping your children begin to understand that their behavior has ramifications that need to be thought through is a long-term developmental process. But you’re already on that road by using this book to help shape your child’s behavior for the long term.

![]()

We’ve now taken you through the basic psychological understanding of your child’s behavior, both good and bad. You’ve learned your ABCs, and know there are an infinite number of contributing factors that can influence your child toward choosing one behavior over another. We’ve discussed consequences and how they can shape behavior (both positively and negatively), and learned that antecedents are equally able to shape behavior but are unfortunately overlooked by many parents.

We’ve also explored situational, internal, and parental influences that are important to keep in mind as you think about your child’s behavior. And, we’ve looked at motives.

Beyond all of this, every parent needs to remember that not all behavior is rational or understandable. This book is all about understanding your child, the circumstances that lead that child’s behavior, as well as your own reactions to behavior. In short, we’ll explain everything you need to know about behavior and how best to prepare for it and respond to it. But occasionally, all the information you have about what’s going on in your child’s life may not be enough for you to figure out why he did what he did. Sometimes there’s just no real reason. It’s okay if you can’t figure it all out, and you shouldn’t let that frustrate you to the point where you abandon your tactics. Chalking it up to “Kids these days!” and moving on is almost always the best bet.

Other Parenting & Family titles from AMACOM:

Parenting with a Story: Real-Life Lessons in Character for Parents and Children to Share

Tell a young person what to do—play fair, be yourself, stick to the task at hand—and most will tune you out. But show them how choices and consequences play out in the real world, with real people, and the impact will be far more profound. Parenting with a Story gathers 101 narratives from people around the world and from all walks of life, reflecting unexpected moments of clarity about who they are and how they should treat others. The lessons illuminate the power of character—integrity, curiosity, creativity, grit, kindness, patience, gratitude, and more—to prepare us for anything.

ADD/ADHD Drug Free: Natural Alternatives and Practical Exercises to Help Your Child Focus

If you’re the parent of a child with ADD/ADHD, you know just how much it affects his or her life—as well as yours. ADD/ADHD Drug Free gives you the natural alternatives you’ve been waiting for. The first book to feature enjoyable, practical activities for children that will help them cope with their disorder by strengthening brain functioning, this life-changing guide shows parents, teachers, and counselors how they can improve learning and behavior effectively and without medication. Timely and thoroughly researched, this guide will help thousands of children become more focused and more successful in school and in life, without jeopardizing their health.

The Un-Prescription for Autism: A Natural Approach for a Calmer, Happier, and More Focused Child

Blending natural medicine with evidence-based science, The Un-Prescription for Autism is a parent’s lifeline. The detailed diagnostic tools, clear explanations, simple protocols, and Online Action Plan support vibrant health on the autism spectrum with safe, natural, over-the-counter supplements. Once the invisible health challenges are tamed, these kids can calm down and break out of their fog, get more out of school and therapy, and become the children you’ve always known they were meant to be.

Home for Dinner: Mixing Food, Fun, and Conversation for a Happier Family and Healthier Kids

Dinnertime has become a rare luxury among today’s busy families. Yet study after study shows that no other hour in your children’s day will deliver as many emotional and psychological benefits as the one spent sharing food and conversation, unwinding, and connecting. Increased resiliency and self-esteem, higher academic achievement, a healthier relationship to food--these and other positive outcomes have been linked to the simple act of eating dinner together.