Chapter 10

Timecode and non-linear post-production

This chapter has been the most difficult to write for this third edition, not because the subject is intrinsically difficult, indeed manufacturers of data management and non-linear editing systems have been spectacularly successful in making their products intuitively easy to use. No, it has been difficult to write because of the enthusiasm these products have engendered in the author! I have tried to avoid turning this chapter into a pocket textbook on how to edit, and I hope I have been successful, but any discussion of timecode application in video-assisted film post-production is bound to touch on the business, if not the art, of editing.

What timecode to record

In the Preface to the second edition of this book timecode was likened to a 'business manager', and like any business manager it can do its job most efficiently if it is involved, and thought given to what type/s of code are to be involved, at the very start of a project, no matter how simple the making of the finished product is likely to be. It is also advantageous to appreciate just how non-linear editing systems handle timecode when material is digitized.

Non-linear systems vary in their timecode requirements. Some will accept only LTC, some are happy with either LTC or VITC, and yet others will call for - and accept - timecode in the ESbus data sent down the RS422 (9-pin) interface used to control the VCR or Telecine remotely. Some non-linear editors will not accept LTC directly, but will record it onto one of the audio channels, from where it can be loaded into their databases. At the time of writing no non-linear editors will accept raw KeyKode® data straight off the telecine, though will accept databases containing such codes generally externally. Most non-linear editors allow material to be loaded in (digitized) without timecode, in which case timecode data will have to be entered for both pictures and sound if accurate EDLs are to be generated. If timecode data is not sent at the time pictures and sound are digitized it will be a great help if 'burnt-in' code (BITC) is displayed within the picture area, and (if appropriate) a matching picture and sound slate is placed at one end or the other of each take. Most non-linear editors can display audio waveforms so a tone slate will greatly ease the synching of sound with picture.

Non-linear editors do not, by and large, store timecode data on a frame-by-frame basis – it takes up valuable memory Instead they load the time address of the first selected frame of a take, and from there onwards calculate the time address, when needed, using the frame count from the last event as an offset. To this extent, it is usually regarded as good operational practice to set any timecode break detection to ON. If set to OFF when digitizing the result could be an inaccurate EDL, as the discontinuity in the code will be ignored.

Options are also available for the loading of the start KeyKode® number of the take, and again there are differences between nonlinear editors as to how this is handled, and for the form in which the final EDL will be presented on disc. Thought should be given as to how any online video edit or negative cutting is going to be undertaken. The organization/s undertaking these tasks should be consulted before the non-linear process is begun, and manufacturers of non-linear editors are invariably encouraging when it comes to asking advice. After all they have a vested interest in making their systems as trouble free as possible. One manufacturer, with a refreshing honesty that does them credit, acknowledges that at the time of writing everyone involved with nonlinear editing is on a fairly steep learning curve, and that there are several data and material handling and management strategies available to progress the route from loading raw stock and blank tape into cameras and recorders to the presentation of the final product on videotape and/or film.

Basic organization of film production using non-linear editing

The organizational principles are the same for both traditional film conforming and non-linear editing to produce a cutting list. Briefly, the following steps are involved:

- Negative is shot in camera.

- Negative has edge number to uniquely label every frame.

- A print is made from the negative. This also carries the edge numbers.

- The print is edited to produce a cutting copy (pull list).

- The negative is cut to match the cutting copy (including any lab process work such as dissolves etc) using the edge numbers as a guide.

- A final release print is made from the cut negative.

Figure 10.1 illustrates the process. The key to the whole process is that each frame of film has a unique Label to identify it. As long as the labels on the original negative and the cutting copy are identical, the conformed cutting list will be what the film editor wanted.

Figure 10.1 The basic process by which film is post-produced. Courtesy of Lightworks Editing Systems Limited.

In non-linear editing the processes are similar, but powerful data management systems allow the editor to perform the cuts (and a limited but growing number of special effects) non-destructively, permitting a degree of experimentation along 'what if lines with an ease that is not possible on film. The data management systems track the various timecodes (original Aaton/Arri, KeyKode®, recorder), check for errors, match pictures and sound shot at different timecode frame rates, and produce EDLs and cutting lists in a variety of formats to suit most online film and video conformers.

As stated earlier, there are many ways of arriving at the final product from the insertion of raw stock into camera and blank tape into recorder. One option could be as follows:

- Telecine transfer film neg or print to videotape.

- Create databases to hold and manage the relationship between the film codes (e.g. KeyKode®) and video codes (this can be done on most nonlinear editors).

- Convert databases into a form that the non-linear editor can handle (if not done on the non-linear editor).

- Record video into non-linear editor (this may be automated using the database to control the play VCR).

- Do the edit.

- Merge the various databases (can be done on the non-linear editor).

- Produce cutting list from the database/s.

- Print the cutting list.

Label options

Labels are the means by which individual frames of film or videotape, and the corresponding audio tracks (either analogue or digital), are identified. Traditionally, electronic editing has treated these labels as separate entities, but it is more helpful if they are thought of generically, with in-camera code, timecode and edge-codes (such as KeyKode®) being thought of as examples. It is also helpful for non-linear editing if timecode is regarded as a label to identify a film or video frame, and not time as such.

Edge numbers

These are recorded as latent images on the film stock. As they carry a code that uniquely identifies the film reel as well as frame number, these codes uniquely identify each frame of film. They are both machine and human readable once the stock has been developed. Edge numbers cannot be used to label sound since they are unreadable on unprocessed film.

Timecodes

Used as labels on both videotape, film and audiotape, they do not uniquely identify every frame as they repeat every 24 hours, and may not carry information about the camera number. The reel or camera number can be placed in the 'hours' digits, the data can be placed in the user bits (see Appendix 7), and at the time of writing there are developments in the ways in which non-linear editors are able to handle user bits information.

It helps if the sound is shot at the same timecode frame rate as the video, as it simplifies the digitizing process, but it is not essential –remember that non-linear editors only regard timecode as a label to identify the first frame of a take – think of audio tape as something that runs at 7.5 inches/second (or whatever) and not as so many frames/ second.

Camera code

Both Aaton and Arriflex use in-camera labelling of film. The labels are recorded as latent images at the time of shooting, and identify each frame, though only Aaton code identifies the date and camera number in the time data. If date and camera number are not recorded with the time data, they should be placed within the user bits, or logged separately, and burnt-in for the digitizing process.

Rubber numbers (Acmade or Ink numbers)

Where picture and sound are synched up on film print and sepmag, the sync rolls are stamped with rubber numbers (Figure 10.2) to help maintain sync during film cutting.

Syncing options for sound and pictures

As picture and sound are recorded on different media, thought needs to be given as to how they will be combined for editing. For non-linear editing a number of options are open:

- Film negative/print and segmag sound can be synced up prior to telecine transfer.

- Film and segmag sound can be synced up in telecine. The process can be automated using camera-generated codes if they correspond.

- Synchronization can be done on videotape, using an edit controller.

- Sync can be achieved at digitization (chase sync).

- Sound can be synced to picture within the non-linear editor (most of which have easy to use utilities or 'tools' to achieve this, and will also give a visual indication when sync has been lost).

However syncing up is achieved, it is important that all the labels will allow accurate tracking back to the original pictures and sound. Each of the above methods has its own pros and cons (invariably trading off simplicity against cost) and it is helpful if either the non-linear manufacturer is approached for advice, or specialist advice is sought at an early stage from a specialist organization, such as a sync suite. A variety of such organizations exist, often using relatively cheap audio workstations (with professional quality sound) and simple edit controllers, and usually equipped with a range of DAT, Beta, Nagra or even disc-based recorders such as SADIE.

Figure 10.2 Super 16 print showing rubber numbers.

Maintaining labels

There are two basic strategies for maintaining the labels during non-linear post-production:

- Store the various labels in a separate database (such as Excalibur or OSC/R) and digitize together with a single timecode such as LTC or VITC (or if available use the facility to have it sent down the RS422 interface). The database must generate matching lists so that the various label types can be correlated to produce the cutting list.

- Place all the labels somewhere on the videotape prior to digitizing (only possible if the non-linear editor is able to handle data placed in the timecode user bits).

Whichever method is chosen it is essential that, for the pictures, KeyKode® and/or rubber numbers and / or camera code plus camera roll or date, and, for sound, rubber numbers and/or timecode plus sound roll or date are maintained. It is also helpful if the videotape reel ident is available on the database for cross-checking.

Figure 10.3 'Burnt-in' display on a non-linear editor, displaying the various time- and film-codes. Courtesy of Lightworks Editing Systems Limited.

If a separate database is created prior to loading into the non-linear editor, it will be converted by the editor into a form that can be used, but it must be in a format and disc operating system that the editor can read. Most non-linear editors accept a range of database files, and the manufacturer can usually give advice as to whether or not a particular database format is acceptable. Aaton's Keylink, Evertz's Keylog, FLEx, Keyscope and FilmLab's Excalibur are commonly acceptable. If commercially manufactured databases are not an option, one can usually be created on the non-linear editor, often 'customized' from one of a range of standard templates provided.

Whether you write information into your database manually, or create it automatically, do remember that the accuracy of the final product will depend on the accuracy of the information held in that database, and (if used) the accuracy of any burn-ins. Figure 10.3 shows an example of a non-linear display of a 'burn-in' plus timecode label, and Figure 10.4 illustrates a typical film database display.

24 fps pictures in PAL

In the past, there has been much confusion about how pictures shot at 24 fps are handled by non-linear editors that work at 25 fps. Possibly the confusion arose because non-linear was a new technology for many, and few editors appreciated that timecode addresses were used mainly as labels to identify starts of shots. Handling film material shot at 24 fps is in fact quite simple.

The telecine transfer is done at 25 fps, straight frame-for-frame. This ensures that each film frame has a corresponding video frame. If sound is synced up prior to digitizing (options 1, 2, 3 and 4 on page 181) it should be played in at 25/24 times its original speed. This is possible on some analogue machines, some recent DAT machines and on earlier digital machines if a correspondingly higher speed word-clock can be provided. If sound is to be synced up in the non-linear editor (option 5 on page 212 or wild track) it should be played in at its original speed. As the non-linear editor will record pre-synced pictures and sound at 25 fps and replay them at 24 fps they will remain in sync. As the editor will record pictures at 25 fps and replay them at 24 fps, separate sound recorded at 24 fps will maintain sync.

If the option to play sound in at 25/24 times its natural speed is not available, it can be digitized at its natural speed, and it will run at a slightly lower pitch in the editor. Keeping track of the timecode addresses is not a problem since, as we saw earlier, time addresses are used simply to label the selected starts of takes.

Figure 10.4 A typical film database display on a non-linear editor. Courtesy of Lightworks Editing Systems Limited.

24 fps pictures in NTSC

In Chapter 5 the business of transferring film shot at 24 fps to 30 fps video using 3/2 pulldown was examined. Some non-linear editors ignore the extra pulldown fields when digitizing, on the basis that these cause movement to appear somewhat jerky. To ignore these extra fields the system must know where they are located. This it usually does by examining the timecode at the sync point and calculating the pulldown fields for the rest of the clip from this point. This can be done automatically on some external database generation and management systems, or by examining a few frames over the sync point on the VCR and checking whether the timecode changes in value from field 1 to field 2. If the film frame at the sync point has been keypunched prior to digitization life will be easier:

| For an A frame: | There will be two keypunched fields, timecode value will not change from field 1 to field 2. |

| For a B frame: | There will be three keypunched fields, timecode value will change between field 2 and field 3. |

| For a C frame: | There will be two keypunched fields, timecode value will change between field 1 and field 2. |

| For a D frame: | There will be three keypunched fields, timecode value will change between field 1 and field 2. |

Digitizing without timecode

If material (sound or vision) is recorded into a non-linear editor without timecode, this need not pose a problem as long as BITC is present. The first frame of the sequence can be located (non-linear editors have a utility for this), and in the case of sound reels, Digital timecode slate is a great help in locating the sync point) and its BITC value placed in the database (again, nonlinear editors have simple to use utilities to do this). In this respect it is worth bearing in mind that some non-linear editors have a BITC facility, which will provide a BITC display, with options as to how much detail is displayed and where it will be positioned on the screen, the value /s being calculated from the labels provided at the time material was digitized. Obviously this facility will not work if no accurate timecode was logged in at digitization, but it can be of use in synching and labelling sound to pictures.

Creating logging databases externally

If you are going to create a logging database prior to digitizing, and import it into the non-linear editor it will be important to check the following points:

- Will the non-linear editor support the particular database? All nonlinear editors are evolving, as are database management systems. Check with all organizations involved in the database creation and transfer (including the manufacturers) if you are unsure.

Figure 10.5 Printout of a typical film logging database containing information on time, footage, roll number, scene, take and date. Courtesy of Wren Communications.

- Will the negative cutters be able to read the pull-list that will eventually be created?

- What time/ film data is to be handled at each stage of the post-production process, not just for pictures but also for sound? Ensure that all relevant codes are loaded into the database.

Different non-linear editors require their externally generated databases to be provided in different formats. All, however, will require the information regarding video and sound parameters (e.g. 25 fps, 48 kHz digital), a header that describes the database layout, and the entries themselves. Figure 10.5 illustrates a part of a typical logging database and Figure 10.6 illustrates three options for logging edge-number and timecode during film-to-videotape transfer.

Figure 10.6 Three options for logging time/footage data: (a) using a film-use timecode generator, (b) using an Aaton computer such as Keylink, (c) using a timecode generator with built-in Arri Decoder. Courtesy of Filmlab Systems International Limited.

Working with external databases

It has been the creation of powerful data management systems that have 'empowered' timecode. Systems such as Excalibur, Keylink, Keylog etc. are more than just databases. They can play a key part at any and every stage of film-with-video-assist post-production. They can not only store time- and footage-related data for film, video and audio tapes, but will handle roll numbers, date, camera number and position (set-up), carry PAL field and NTSC pulldown field information, and even provide a means of logging information needed by the colourist. They may generate VITC for the video that will be digitized into the non-linear editor, and even log external GPI events such as might come from the telecine's colour controller, such as Pogle®. Not all of this data can be transferred with the video, certainly not in the user-bits of a single frame of traditional timecode. One manufacturer arranges for all this data be carried as 'tags', stored in three VITC lines (lines 19, 20, 21), within the user bits of one VITC line, with another line (the KeyKode® line) carrying edge numbers in full, and the third line (the real-time line) carrying time-of-day. Figure 10.7 illustrates a typical display provided to a colourist at the end of a transfer session.

Figure 10.7 At the end of a session the colourist can view and print the details of the transfer. Courtesy of Aaton des Autres.

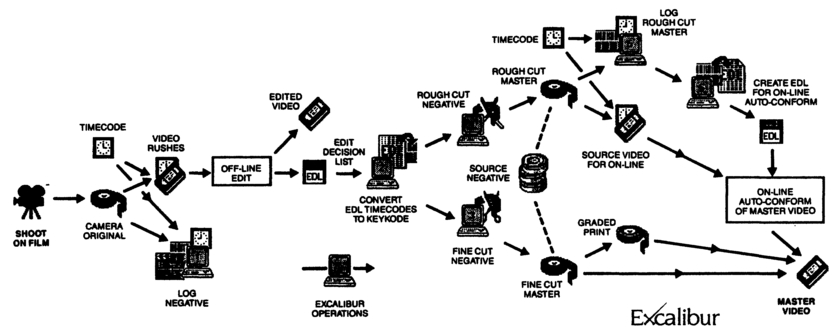

With much television material being shot on film (for quality, the film look and the wide-screen format) for later mastering onto videotape, data management systems can be used at all time-critical stages of postproduction; for negative logging, providing an edge-number edit list for a rough-cut assemble of the negative and, after assembly of the rough-cut, an accurate EDL for auto-conforming the on-line. Figure 10.8 illustrates a typical sequence of operations.

Figure 10.8 Options for film-to-video post-production using a data management system. Courtesy of Filmlab Systems International Limited.

When the final product is to be released on film, data management systems can be involved at the initial logging of the negative; for later conversion of the off-line video EDL to a matching KeyKode® list; for organizing a frame-accurate cut list for providing the check print; and lastly for providing any modified cut list for the fine-cut of the source negative. Figure 10.9 illustrates two typical film-to-film post-production processes.

Figure 10.9 Options for film-to-film post-production using a data management system. Courtesy of Filmlab Systems International Limited.

Doing away with the external database

Top-of-the-range non-linear editors no longer require external databases for the management of time and footage codes. Camera and Telecine manufacturers provide options that permit 3-line VITC to be encoded onto the videotape at the time of transfer from Telecine, and non-linear editor manufacturers have developed a range of 'template' options for internal database management systems. The data thus encoded into 3-line VITC (see Chapter 5 and Appendix 8 for details) can be loaded into the non-linear editor at digitization, being carried either in the video signal to be digitized, or via a separate physical link. Once in the editor, internal database management systems, coupled with EDL and cutting list generators can provide just about any option required.

The future?

Manufacturers of non-linear systems are working on increasing the time-data options that they can accept during digitizing (as opposed to relying on databases generated externally), more and more routes are being mapped out for the journey through film-to-film and film-to-video postproduction. Video with 3-line VITC is now available to the non-linear editor straight from the camera's video assist facility (though obviously without key numbers). This will allow an off-line editor, on location, in conjunction with the Director, to decide whether or not a scene needs to be reshot for editability and/or continuity. At least one manufacturer of non-linear editing systems is actively exploring the possibility of transferring digital audio data to audio workstations without having to do it in real time. The same manufacturer is currently developing a database management system that will permit sync sound to be digitized separately from the pictures, using 3-line VITC to marry up sound to picture within the editor, and an option to discard unwanted audio. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, with the cost and size of memory both coming down, non-linear editing is now becoming available in broadcast quality.