Ancient Societal Infrastructures Originating in and Supporting Commercialism

Ancient cross-territorial trade, the prime root of globalization, effectively changed the world. The need to establish the first vestiges of communication within and between varying social groups was to assist in the bartered exchange process. The establishment of social mobility corridors was beholden to ancient trade passages. The initiative for developing faster and more efficient transportation inventions, from new forms of transportation to navigation tools, was the business imperative. The impetus for urban planning and the resultant architectural designing and construction of physical infrastructures was a response to the need for market centers. The increasing levels of civilized development around the world were built on the commercial imperative.

Trade: An Innovator of Communication

John A. Pierce, an American engineer in the field of radio communication, felt that communication was at the core of what makes us human and served as vital asset to sustain life.1 It is therefore a key element in the construction and maintenance of civilization on Earth. The historic progression from savagery or barbarianism to a civilized society “included the development of agriculture, metallurgy, complex technology, centralized government, and writing.”2 The definition of the term “civilization” denotes “a relatively high level of cultural and technological development; specifically the stage of cultural development at which writing and the keeping of written records is attained.”3 Without communication, language in its oral and written format, the world would not have developed. It is the essential ingredient in the building of human civilization on Earth. It is the way people express themselves—their needs and desires. It is the primary method for passing ideas, recording events, and practicing learning. Without it mankind would not progress. Improvements in language and the emergence of the written recorded word can be directly traced to the commercial imperative.

The requirement of language between people grew out of the process of exchange—the trading imperative. It was essential for man not only to offer one thing for another with his neighbor in order to simply survive but also to expand and improve life. The concept of barter furthered the need to communicate even when people lived in close proximity to each other. They traded with one another, as all of them were in pursuit of the same basic things. As such they had to have familiar words in order to accomplish such primary goals. As people explored territories beyond their normal living borders they encountered others in the trading imperative. The theory of Sprachbund, a convergence area for groups of people who ultimately end up sharing parts of a common language, was created. Sprachbund is German for “a shared linguistic area.” It is an ensemble of areal features—similarity in grammar, syntax, vocabulary and phonology—that results in common understandable messages passing between people. This principle of communication began in ancient times and was based on the need for different cultural groups to exchange their local resources with one another. While a universal language has never been forthcoming, one sees the same principle continuing today at a greater increasing degree and scale. Ask for a “Coke” today in almost any part of the world and the request is understood. The language of computers and electronics is becoming universal as is the recognition of international brand names. The trade factor is responsible for the increased phenomenon of Sprachbund as commercial globalization has allowed for common terms to be included in all languages around the world.

Up to the Middle Ages, the world was illiterate. The limited written word resided in the hands of the royal houses, their administrators and court-appointed artisans, and in many cases, the clergy. Recorded knowledge was used for imperial and religious purposes, something not learned by the common man. Its first extensive public use, however, was for the recording of commercial transactions between common folk. Historically, the merchants were the pioneers in bridging different languages. Out of necessity they created common trading terminologies, beginning with transcontinental material value assessment among and between varying cultural groups. They influenced the spread of shared linguistics and anthropology as they traveled the world in search of trade. It was the early traders that gave the world universal values of exchange, like gold and silver, so that a common appreciation of similar values could be developed. They created universal standards of measurement so the exchange process could be unified and expanded thereby bringing people together.

In the beginning, instead of using the alphabet, symbols were grouped together to communicate the exchange of ideas, thoughts, and representations. The concept of a syllabary was created: a system of symbols that denote actual spoken syllables. The first use of printed or stamped images and drawings on the walls of caves tends to be identified with storytelling, detailing the exploits of the residents. In the Indus region (India) over 4,500 years ago, bales of goods for shipment were wrapped with seals applied. These rudimentary identification signs allowed the receiver to recognize the geographical origin of the goods, presumably ascertaining their unique territorial source, which adds to their intrinsic value and reorder. These notations on exported goods, which authenticate them as produced in regions that consumers associate with high quality and superior workmanship, is still used today. The markings are considered the forerunners of trade marketing even though they originated as a geographical classification. Today, goods in their packing literature indicate their country of origin, the name of the manufacturer, and often include a demonstrative identifier like a trade name or trademark to further establish their uniqueness to the public. In India these commercially induced inscriptions are indicative of an early form of literary that bears resemblance to such use that is also found in the early Greek Minoan civilization. The Minoans may have also created the first vestiges of commercial product identification in Europe as did the Harappan of India in 2250 BCE. The Minoans used clay seals on individual products. Today, the museum of Heraklion in Crete contains a huge collection of seals carved out of clay, stone, or very fine hardwood that were used to mark merchandise “in a way that made it traceable to a particular point of origin.”4 Such mechanisms may have been the first accepted system used by merchants and consumers in the Mediterranean to differentiate competitive resource centers or producers of traded goods. Such markings used on bushels of goods by the Harappans and the Minoans were the forerunners of differentiation marketing strategy and branding—that is, the advertising information on the packaging and the “made-in” territorial designation.

Some archeologists examining the Minoan markings on clay seals placed on individual items discerned a reference, perhaps to the Greek deity Artemis, when phonetically pronouncing the symbols as a-ra-tu-me. Researchers have considered that such markings adorning the products with the name of the goddess of the wilderness connoted that the products possessed the goddess’ characteristics: fertility, strength, and health—a kind of celebrity endorsement to trademark and identify goods in the modern commercial sense. No empirical nor accepted science has verified such a theory, but the idea is intriguing as the concept of using heroism as a marketing tool (as noted in the previous chapter) is used extensively today. Other Minoan clay tablets have also been found showing terms for commodities and transactions.5 In the previous section on the development of ancient trade, Minoans’ use of their symbolic writings as an accounting tool to record commercial transactions is referenced.

The early Greeks were great transterritorial traders, and due to their vast commercial explorations Koine Greek was the lingua franca or working language of business in the Mediterranean and the Near East for centuries. The word Koine itself means “common,” a suitable designation for a language that allows communication exchange for diverse people. No matter their spoken native vernacular language, educated literate people communicated internationally during the period from about 300 BCE to the close of ancient history around 500 CE using Greek. Translations from the originating languages of numerous cultures into classical Greek texts helped preserve learning while also assisting its expansion around the world. The New Testament, formed from various gospels composed by people living in Palestine who spoke Aramaic, was circulated throughout the world through Koine.

Basics of the language developed during the classical era and were spread abroad as ancient Greek merchant seamen carried it with them thereby forcing foreign parties desirous of forming business relationships with the foremost cross border traders of the day to learn and accept it as the first language of international commerce. The language was expanded by the armies of Alexander the Great and his colonization of the then known world after the postclassical period and continued as the prime collective language through the time frame referred to as medieval Greek and the start of the Middle Ages. Koine not only became a common standard for commercial dealings in most of the Western world, even surviving the Roman period, but also was the prime learning language for knowledge expansion as well as the prime link in cross-cultural translations for important texts and documents. Koine shares a unique comparison with English in modern times. Both languages, due to the respective strength in specific historic time periods of their national economics and the global reach of their businesses, greatly influenced the rest of the world. They each became the second language of choice of international traders, which in turn impacted the domestic societies they came from. Many of the words and terms found in today’s array of global languages have roots in Koine. The universal spread and use of Greek is primarily attributable to the extensive travels of global traders originating in the Greek region as in ancient times there was no nation called Greece, just a collection of kingdoms.

From the Greek word embalo we get the English word “emblem,” a stamp of authenticity to indicate the genuine article. Consumers rely on such markings in their buying decisions around the world today. Trademark designs such as the Nike swoosh, the Ralph Lauren polo player, and the IBM initials not only identify the products of these corporations as authentic but also act as advertising beacons on stores shelves and packages themselves. They also inform the consumer of their social status. Global companies allot vast amounts of their expenditures to create and sustain product and service images, which are known by their corporate and individual trade names. The protection of these valuable assets has produced both national laws and supranational regulatory registrations for such proprietary rights. They are the subject of countless litigations and form part of worldwide trade administration. Both these ancient societies summarily drew from an exchange imperative to construct such designs and create an initial written communication vehicle from which a written language was constructed. The process itself also contributed to an advanced developmental stage of culture as writing in any message format, as noted earlier, is a prime criterion for progressive civilizations.

The ancient trading process was a key contributor to such consideration, as the earliest writing in the Mesopotamian and the Minoan societies were pictograms of memoranda, lists of goods or receipts as “their emphasis is economic.”6 The same attribution is found in Egypt, China, and depicted in the Inca civilization. All these ancient societies used the wonderful new skill only to keep records,7 of which most pertained to exchanges between individuals of traded goods.

The cuneiform markings of the Sumerians placed on clay tokens in 3000 BCE were characters representing numerals to quantify amounts and the names of such objects like sheep, amounts of grain, and reams of cloth, which are all daily traded commodities. The intent was to record possessions of people8 and how they changed over time; representative of the bartered transactions between them. It also recounted the accumulation of wealth, which could be taxed by authorities. Essentially, the first Sumerian texts contained a clerical accounting system that included records of goods paid to the central government and agricultural rations given to workers. Only later did Sumerians progress beyond “logograms to phonetic writing,” which included descriptive “prose narratives, such as propaganda and myths.”9

The writing of the Sumerians predated Egyptian hieroglyphics by 250 years and replaced the Neanderthal pictographs found on cave walls in prehistoric times. As the Sumerians expanded trade with their neighbors around 2500 BCE, their written language found its way into other cultures. The Phoenicians in 1100 BCE adopted a phonetic (sound based) alphabet, a radical departure from pictographs and cuneiform scripts. They instructed their associates encountered on foreign trading missions in this new form of written communication and the legacy of such an introduction in the Mediterranean region was the foundation for modern-day Western languages. Recently archaeologists have unearthed 4,000-year-old tablets representing some of the oldest and perhaps first written trade agreements in the area of Anatolia, Turkey. These cuneiform-script writings in the region occupied by Assyrian tradesmen contained recordings of transactions in tin and fabrics with businessmen in Mesopotamia.10 The development of the written word owes its importance to recorded wealth creation and its distribution, both constructed on the first vestiges of organized commercial trade dealings and the earliest recorded heritage of modern globalization transactions. The Sumerian language, originating as a trading communication device, has survived for over 6,000 years. So basic are its properties that it was included in the September 5, 1977, interstellar mission of the spacecraft on one of the Voyager Golden Records. This unique phonograph record contains sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. It is intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form, or for future humans, that may find it. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University Of the 47 earthly languages recorded on the disk the first is Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about 6,000 years ago, and due to Sprachbund, is in essence the Sumerian text.

Today business to business and business to the final consumer take up a great portion of the communication that transpires around the world. Internet sites that help one navigate the knowledge network are endowed with commercial advertising while television programming abounds with commercials every few minutes. The exchange of information by companies, both internally and externally, via wireless technology, telephones, and computers competes with private messaging and is a key component in the establishment of international business. The ability of host countries to provide a comprehensive communication system is a key factor as MNCs decide on which markets to enter. Communication is the rail on which the exchange process moves and hence the need for advanced technologies to support trading practices was a natural outgrowth of the commercial imperative. From record keeping to transactional dialog to the modern age of information, gathering business has been both a motivator of and a prime beneficiary of advances in communication technology. In the modern era, trademarked goods in the language and pronunciations of one country are being transmitted identically around the world. Such universal sharing of language in both written and verbal communication has helped unite populations through the commercial imperative. More and more brand names with distinctive identification logos and accompanying symbols are recognizable by larger audiences of consumers around the world than ever before.

Early Roadways

The first roads created by humans, even back in the Stone Age were for the cartage of goods that often moved over game trails used by hunters such as the Natchez Trace used by Native American Indians in the southeastern United States. Improvements to these initial paths consisted of clearing trees and large stones along with the flattening and widening of the carved way to accommodate farms goods destined for local markets and then for the movement of larger commercial shipments of merchants. These early roadways—which in some civilizations like the extensive Incan Empire in South America and the Iroquois Confederations in North America, neither of which had the wheel—had massive interconnecting networks to mainly facilitate trade among other regions. The Incas of Peru traded up and down the Pacific coast of South America and may have been visited by the Polynesians of the South Pacific on mutual exchange trips. A large, diverse collection of crops, yielding vast amounts of products created by artisans from such raw materials, was transported by sure-footed llamas over sometimes torturous but well-established trade routes stretching from Argentina to Colombia and across the mountains to the tributaries of the Amazon and on to the Brazilian coast. On the four highways emanating out from the great plaza in Awkaypata were constructed state warehouses or way stations for trading. Even though Incas did not have knowledge of the wheel nor the use of horses (the Spanish conquistadors introduced them), networks of well-constructed roadways, the most extensive built in the Americas (many still existing today), has been compared to and perhaps eclipsed those built by Rome. The Inca road system called Capaq Nan or Gran Ruta Inca has been estimated to have exceeded 40,000 km (24,855 miles). It consisted of two main arteries: one just adjacent to the western coastline of South America running between Tumbes in Peru and Talca in Chile and another through the Andes highlands linking Quito in Ecuador and Mendoza in Argentina. Numerous additional routes lead across the empire with the most famous being the Inca Trail from Cuso to the ruins of Pachacuti, known as Machu Picchu. As the various routes were intended for foot traffic accompanied by caravans of sure-footed llamas as pack animals, the roadways were constructed of stone cobbles with the addition of rock steps or stairways to traverse mountainous paths. Many were just dirt pathways with the ground padded down following the footprints of travels and hence only 1 to 4 m in width. To assure navigation through various terrains, bridges, culverts, tunnels, and retaining walls with elaborate drainage systems were constructed to assure safe travel during the rainy season. Placed 20 to 22 km along the more well-traveled commercial routes were a series of tampu, small clusters of buildings forming tiny villages that provided food and lodging for business travelers. Although not as extensive as the caravansary found along the Silk Road, they offered a respite for merchants, serving as a gathering place for the exchange of information and some trading activities. The Incas deeply upheld the need to keep these commercial passages well maintained as they were the lifeline of the empire.

Stone—crushed or whole—and other strong materials for street paving within crowded cosmopolitan settlements have been found in the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization on the Indian subcontinent of Harrapa and Mohenjo Daro. The Greeks used similar methods including marble fittings to accommodate the movement of citizens in their cities with the key objective of furthering the commercial exchange process between them. In the city of Ephesus in southern Turkey (founded in 281 BCE), the major street, Curetes, to this day supports tens of thousands of tourists each year, a testament to the excellence of the original stone composition. The Romans took the construction of highways to a new level. The phrase “all roads lead to Rome” is not so much a metaphorical reference to their early dominance of the world but to the recognized fact that their territorial colonies were constructed as commercial resource centers to serve the needs of and increase the wealth of the empire via the most extensive network of roadways the world has ever seen. With over 180,000 miles created, and at the height of construction averaging over 1 mile of new roadway every 3 days, such still standing remnants like the Apian Way were the lifeblood of the state, allowing trade to flourish and the Roman Army to move around. In ancient Rome, farm roads were paved first on the way into towns in order to keep fresh produce clean on their way to metropolitan markets.

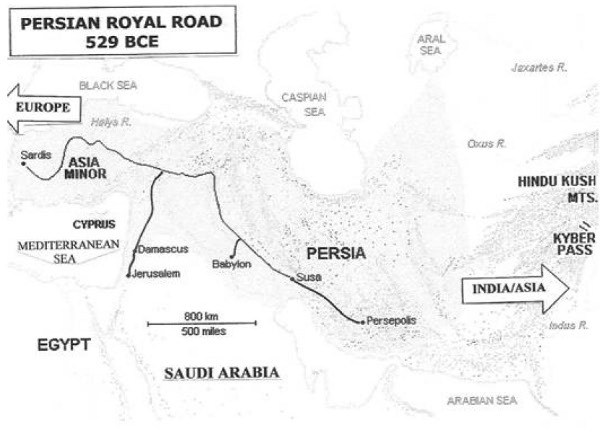

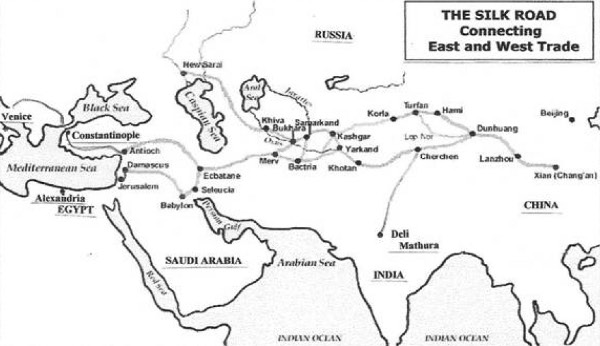

The Persian Royal Road, not be confused with the King’s Road out of Egypt that also had royal heritage, was enhanced by Darius the Great in the 5th century BC. Covering just over 1,677 miles, it effectively linked Asia Minor with the eastern part of the continent. The roadway was initially constructed to facilitate efficient communication across the empire, a reported 7-day journey by rapid continuous horseback, an early version of the western American Pony Express. The highway ran from Susa, the capital of the kingdom, to the southeast city of Persepolis near the Indian subcontinent, while moving east to Sardis on the Aegean coast of Lydia (modern Turkey) and down to Babylon in the south (see Figure 6.1.) Centuries later this vast road system would intersect with remnants of the aforementioned King’s Road across northern Arabia and other local trade routes in India and China to form the cross-continental network commonly referred to as the Silk Road (see Figure 6.2.)

Persian Royal Road

The Silk Road

In the Middle East vast roadways were built specifically for the extensive Arab-led merchant trade. Perhaps the most sophisticated systems were found in Baghdad. Built under the insistence of the caliphate in the 8th century, they were paved with tar, which was derived from petroleum extracted from oil fields. The finished surface therefore resembles many of the modern street and highways found around the world today.11 All of these ancient road systems were the forerunners of a common national goal, the creation of an infrastructure to enable commercial development of their lands under their control and to encourage trade with neighboring regions. The echoes of the ancient roadways like the King’s Road, the Royal Road, the Incense Road, the Silk Road, and even the little known Tea Horse Road invoke memories of the valiant merchant traders who used these commercial ancient highways to further social exchange connections, which contributed to the development of civilization and paved the way for modern globalization.

The Silk Road was a contemporary name given to describe a system of interconnected complex merchant routes that linked the East with the West through the caravan city of Palmyra in Syria and from there to the Mediterranean (Europe, North Africa, etc.). This early transcontinental caravan highway may have begun with the Han dynasty in 206 BCE, as the royal house reached out through appointed intermediaries to the steppe nomads in search of horses, glassware, gems, and other products from the West. This collective series of trade routes survived the demise of the great Han and Roman Empires, reaching its zenith as the world’s prime commercial corridor during the Byzantine and Tang Kingdoms in the early Middle Ages. By the 11th century this fabled land route connecting East and West, and later receiving the namesake of its most valued commodity that moved across it—silk—was in decline due to the intense competition from Indian Ocean merchant shipping and later during the age of discovery, as traders developed routes rounding southern Africa, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific.

Early Transportation Devices

Archaeologists consider that the initial step toward the development of man-made transportation devices began somewhere between 4000–3500 BCE with the invention of the wheel in either Mesopotamia or Asia. While the domestication of horses and oxen enabled and assisted early farmers to more efficiently till the soil for crop planting, the introduction of the wheel was followed by that of the cart and chariot—devices that made the transport of crops from one place to another less awkward and more labor economical—as increased quantities could travel over greater distances. Eventually, the four-wheeled cart took the burden of carrying products off the shoulders of the common man and increased the load capacity of beasts of burden. The chief beneficiary of this technological advancement was trade and exchange, as it paved the way for the establishment of centralized destinations for transactions—the marketplace. It also allowed for the concept of competition to enter the commercial matrix, as previous individual agricultural locations needed to be visited and only singular concealed transactions could be completed.

While the wheel enabled man to overcome the cumbersome boundaries of land travel, his ability to also transit bodies of water was collaterally approached. Researchers tend to conclude that the first water transport vehicle was the dugout canoe used in rivers but the actual inventors are hard to pinpoint. This transport device also allowed for the movement of goods over natural water highways, again contributing to trade expansion over greater distances and with added economic efficiency although the power to move across water had to be supplied by man or with the manipulation of the river current. This engineering drawback led to the invention of the sail to harness the wind. The Egyptians are credited with inventing the sail, as living next to the Nile it was imperative that the navigation of the lifeblood of their civilization include such a technological advancement. The attaching of a cloth to the central pole of the vessel turned it into a self-propelled machine. Eventually, the addition of oars and rudders, then deck coverings in Greek and Roman times, provided better steerage as well as storage areas or shipboard towers to carry men and supplies. Such alterations in design developed into the medieval stern and forecastles as part of the ship’s basic design. During the European Renaissance and the age of exploration, oceangoing ships gained tiers of rigging and rows of sails while also becoming sleeker, adding speed and agility to them and thereby making long-distance travel faster and safer. The progress in such water-travel vessels was collaterally aided by the advent of more precise map-making and open-water navigation tools based on astronomy. The Arab, Indian, and Chinese merchants, due to the lure of the spice trade across the Indian Ocean but originating in the so-called spice islands of southern Asia, studied the heavens for directional consideration, and it was the impetus of trade across continents that propelled the quest for such innovative and imaginative astronomical observation and knowledge to be developed. The Chinese invented the compass, although its initial motivation was as a land structure building device based on the spiritual desire to construct homes facing north. About 70 years before Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to find a westward route to the riches of the Far East, the Chinese in 1421, under the command of Emperor Zhu Di’s finest admirals, launched the largest fleet the world had ever seen. Called the Star Fleet, it consisted of 3,750 ships, the centerpiece of which were 250 enormous 9-masted treasure ships that were each estimated to be over 500 ft. long. Columbus’s ships—the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María—could, all together, fit on its deck. The mission of this armada was to sail the oceans of the world, chart them and their lands, while bringing the territories explored into the orbit of Chinese influence including Confucianism and the royal tribute system. Such a task was to be accomplished by extending trading privileges coupled with protection from enemy aggression.12

With the growth of trade via water-based routes and the advent of better-equipped larger cargo ships it was natural that the construction of ports would follow. Around 2250 BCE in the Indus region of what is today India a civilization emerged that some call the Harappan, who valued external exchange with neighboring territories, the import-export principle. This was exemplified by their construction of a vast dockyard complex linked to a mile-long canal to the sea, enabling area merchants to reach as far as Southeast Asia and the legendary spice islands through the Persian Gulf. The port dominated the landscape and was larger in scope and size than any temple or public edifice, attesting to the importance of the commercial trading imperative to this ancient civilization.

While Roman roads were vital in the maintenance of the empire, many of them were connected to ports, a growing source for the importation of valued commodities. Perhaps the most important stretch of highway was between Rome and the port city of Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber River, a distance of 15 miles. Grain to feed Rome was delivered from Egypt, the most important of the many foreign sources of supplies to the empire. Merchant ships also arrived from the North African city of Carthage as well as Hispania (Spain), Gaul (France), and even from as far as India and the Far East, all unloading their regional cargo, which in turn was placed on barges in transit to the capital city. Ostia was a major geographical player in the tactical downfall of Rome in 409 CE when it was captured by Alaric the Goth by starving the population of Rome into submission. The port city is also the starting place for the popular political rise of Julius Caesar, perhaps the most well-known Roman emperor. During Caesar’s early military career he was assigned the task of ridding the lucrative and necessary commercial sea-lanes in the Mediterranean from the marauding pirates. As a commander of the Roman navy (much like the exploits of the later noted American Navy and the Barbary Coast pirates), his success in the campaign become the launching pad for his rise in the army ranks and eventually earned him fame and glory.

As the Roman Empire began to grow it patterned many of its foreign territorial trading city centers on models developed in the home country. The Roman Empire’s trading excursions far outstretched their military conquests and the parallel establishment of colonies under their rule. Italian-based merchants via overland trade routes through Anatolia and Persia made limited entries to the eastern lands while also trading with middlemen in the Kingdom of Axum (Ethiopian), which transacted directly with India. In the beginning of the Common Era, during the reign of Augustus Caesar, the conquest of Egypt opened up a southern water route to these lucrative trade regions. During the occupation of Egypt the most important trading outpost was the port of Berenice (Berenki Troglodytica) on the Red Sea. Merchant ships from this strategic port sailed the Indian Ocean to the Malabar Coast of India. After nimble seagoing captains learned the secret of the mason winds, seasonally blowing both East and West, the journey was reduced to 45 days and allowed for a safer route than the old long and dangerous coastal path that was beset with traitorous offshore reefs that destroyed the hulls of cargo ships.

Archeologists have uncovered precious parchments detailing not only the navigational directions but also information on exchange techniques—the secrets of getting the best deals from traders in the Far East. Perhaps the most valuable cross territorial freight of the day was incense and spices including pepper. The Roman amphora, the holding pottery jar, was the vessel of choice for these prized foreign-grown resources, and the capacity of small ships was up to 3.5 tons of these containers. The average shipment was valued at 7 million drachmas or $270 million at current exchange rates. Larger merchant ships had a 7-ton capacity and averaged 120 trips a year. Over five-and-a-half centuries, the cumulative value of the Roman-Egypt trade with India and the Far East is estimated at $10.5 trillion, a vast sum even by today’s financial measurement and a testament to the globalization of the ancient world.

After unloading these resources at Berenice, they were moved inland via caravans some 200 miles from the Nile River and onward to the Mediterranean port of Alexandria, previously built by the Ptolemaic dynasty for commercial dispersal across Europe and one of the grand ports of ancient times. Roman garrisons were strategically built on the mountains surrounding Berenice and the overland route to the Nile to guard against attacks on the merchant convoys. Records maintained by the Roman overseers in the area indicated that duties for the movement of everyone and everything were extracted. People were taxed according to their vocation or skill. Prostitutes were charged a flat fee of $2,700 to enter the city of Berenice. Owners of donkeys and camels, the means of transport, were charged according to the animal’s size while trade goods were taxed at 25% of their anticipated value. The profit to be made in the physical movement of just about anything in the region was so enormous that such a mandated additional expense was not prohibitive. The port city of Berenice consisted of a multitude of international nationalities with over 11 different languages both spoken and written. Merchants who plied their trade in the region made enormous fortunes generating more income than the combined cities of New York and San Francisco do today. All this ceased after the fall of the Roman Empire in Egypt when Muslim armies overran their dominance of the Egyptian territory and the military protectorate of this lucrative trade route was lost. While this trading outpost proved to be a most beneficial wealth creator in the ancient world for Rome, the route to India and the Far East also allowed for the parallel exchange of cultures to take place, contributing to the growth of civilization, a valuable antecedent to the commercial process. Social ideas moved with goods as merchants brought their customs, traditions, and beliefs with them. Mythical stories have circulated that have Jesus himself traveling on Roman merchant ships bringing the preaching of his gospel to these new lands while more tangent evidence suggests that the Apostle Thomas may have started a Christian mission in India using such commercial routes. In later centuries, the emergence of Islam in the Middle East also made its way on the trails of merchants traders to India and onward to Southeast Asia as represented today by Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim nation. In reverse, the teaching of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism found their way into the Indian subcontinent through the use of similar commercial dealings.

The construction of roadways in antiquity, the emergence of ancient seaports as water routes emerged, railroads in the industrial era and airports in modern times are all examples of physical infrastructure to support the exchange process and the maturing commercialization of the global environment. To allow for continued and expanded trade, both internally and beyond bordered territories, such technological advancements have always endeavored to further connect the world by shrinking the movement of goods into a more manageable system that is efficient, seamless, and cost efficient. The process continues today. Multinational companies are using their foreign direct investment (FDI) funds in emerging nations not just to develop commercially valued enterprises but to contribute on a collateral basis to the improvement and modernization of the infrastructure. In Africa, Chinese quasi-governmental investors are marshalling their capital funds to primarily target the ore industry as well as other business projects with either outright contributions or soft loan arrangements to improve transportation infrastructure and communication facilities. Such technological advancements were necessary in the economies of the ancient world and they remain so today. From the building of new roadways and seaports to the refurbishment of dilapidated railroads, such developments propel a civilization forward and are a necessary component to further the global exchange process (they go hand in hand). Transportation, throughout history, has spurred territorial expansion and served as a precursor for modern globalization, as better transport devices allowed for more trade and a greater spread of people. Economic growth and the progression of civilization have always been dependent on increasing the capacity and rationality of transport.13

The Brick and Mortar of Ancient Trade

While roadways and advances in transportation played key roles in the globalization of trade in the ancient world, local store merchants serving the final link in the commercial chain, consumers, pressed authorities of ancient municipalities to provide better commercial infrastructures. Historically, town or village markets are naturally active around harvest time, when area residents gathered to exchange the fruits of their labors for those produced by others. The idea of a year-round marketplace that was a permanent part of a city infrastructure was introduced in antiquity and remains as a central planning tool for municipalities around the world today.

The concept and type of business models have constantly evolved through commercial history. A very basic and popular model, since ancient times, has been the “shopkeeper model,” which involves establishing one’s store in a location that is most likely to attract potential customers and make it easier to advertise the products or services being offered.

The Greek-inspired agora was the forerunner of the modern-day indoor shopping malls and centers. These retail centers, examples of which still exist today in places like Ephesus in Turkey, were founded for a second time by Androclus, the son of Codryus, king of Athens. The city, with a sheltered harbor, was described by the historian Aristo as being recognized by all the inhabitants of the region as the most important trading center of its time in Asia. Made up of colonnades that protected pedestrian walkways from wind and rain in the winter and from the sun in the summer, the architectural design originally supported an open-air market measuring 110 ×110 m. These outdoor stalls were converted into rows of permanently built shops of alternating or next street entrances so customers could come and go without store owners seeing which shop they came from. The fronts of the shops opened into vaulted store rooms at the back for a year-round protection of inventory. Signs were erected above the doorways with symbolic renderings of the merchandise available inside. Tourists visiting the site today still play a game of trying to identify the goods through the restored sign images archeologists have placed on them. Perhaps the most well known of the artifacts of Ephesus is a relief on the Marble Road depicting a left foot, a portrait of a woman, and a heart decorated with perforations, referencing the city’s brothel. Such a graphic depiction is perhaps the ancient world’s first outdoor advertisement, a precursor of American billboards that punctuated automobile roadways in the 1950s and the genesis of the commercial advertising industry today.

Shopping in ancient Rome was much like shopping in today’s commercial environment. Rows of stores offering their wares could be found on the main streets of the city, which had specific areas devoted to specialized product categories. Like the Greek shops before them, elaborate signs adorned their entrances advertising to the strolling public the merchandise to be found within. Many were constructed using colorful inlaid mosaics while others were paintings. Besides the public signage, store owners were required to prominently display a government license, a document permanently sculpted in marble, to trade in particular categories. The idea of a license to service the pubic served a twofold objective. It allowed the government to keep an administrative handle on market trading activities and to collect a fee and thereby finance the municipality’s treasury. In addition to the shops selling both everyday and luxury goods, there were food and drink stalls for the plebeians and slaves shopping for their masters, a forerunner of the food courts found in today’s modern shopping malls. Most shop proprietors did not use employees to run their operations but instead purchased slaves. It was not uncommon for shops selling exotic imported merchandise to also utilize slaves from the foreign region that produced them, thereby creating an atmosphere that consumers found appealing and different, which is a concept today’s retailers aim for—enhancing the shopping experience.

Beyond the commercial infrastructure of street shops, ancient Roman city planners introduced the concept of the forum or dedicated market and business center. Most noteworthy were the basilicas, not to be confused with large church buildings constructed during the later development and spread of the Christian faith. These commercial basilicas were several stories high and contained a variety of consumer services from business offices to lawyers and accountants along with rows of specialty shops. This mixed-use structure is still employed in modern commercial development projects.

Trajan’s Market (in Latin, Mercatus Triani), the last great structure in the Roman Forum, is thought to be the world’s oldest metropolitan shopping center. Constructed in 100–110 CE on a semicircular design, it sat opposite the Colosseum, positioned perhaps to attract spectators at the games. The entry to the vast marketplace was made in travertine surmounted by an arch. The ornately decorated interior hallways were made of delicately cut marble while the outside walls used bricks. It was roofed by a concrete vault raised on pier acting both as a covering and to allow air and light in the central space. The remarkable architecture of the building is considered a wonder of the ancient world as its splendor was not only to attract customers but also to proclaim to all citizens the symbolic embodiment of the grandeur of the Roman Empire.

This early tiered marketplace rising six stories high contained over 150 shops and administrative offices, with medieval apartments on the top floor added later. Such mixed use of structure became a model of urban planning and the concept is still in use today. Shops on the ground level floor featured fresh produce of the day as well as taverns while those on the second were primarily devoted to olive oils and wines. The third level was for grocers’ specialty shops along with exotic imported items such as rare incense, silk cloth, rare gems, ivory, and a host of foreign products collected from the far regions of the empire. Although the shops varied in sizes, most were rather small. Customers would most probably approach the shopkeeper at the door and make their purchases without entering the room itself. The chief reason for such a buying procedure is that the bulk of the premises was devoted to inventory warehousing as opposed to display selling. Patrons would rely on the expertise and recommendations of the shop merchant, a common practice in those days and still found in small traditional villages across the globe.

The remnants of the infrastructure still found in the Roman city of Pompeii are good examples of the commercialization of an ancient international port city. The explored ruins of the city reveals the use of a large banking facility for foreign specie trading as the international clientele of the city arrived with varying mediums of value (coinage, gold, and silver as well as precious stones from their respectful lands) all requiring the services of local money exchangers that made a market in such transactions; the forerunner of today’s global currency arbitrators.

Vast markets or bazaars for all varieties of exotic imported goods, erected and maintained by the municipality government, dotted the landscape. Such an action served a dual purpose: (a) it provided a protected commercial environment for the stimulation of business and (b) allowed for direct oversight to insure proper payment of a transaction levy, the precursor of the municipal sales tax. The city’s main entertainment attractions were its 80 wine bars and 28 houses of prostitution, many based on interlocking ownership, an early use of the franchise concept. These establishments were often connected by adjacent alleyways, kind of a cross product marketing promotional program that many companies use today. Even the brothels contributed to the growth of the commercial advertising process using, like the Greeks before them, signs of their services in the form of phallic engraved street carvings directing potential clients to their premises. In these establishments they catered to the foreign visitor via the use of menu-like murals on the walls to get around the numerous language differences—customers only needed to point to receive the services they desired. Today internationally directed products also use diagrams and illustrations to explain their product benefits and instructional use. Specialty craftsmen such as bakeries provided the impetus for modern-day marketing concepts. Their individual breads were branded with a hot iron featuring a symbol to identify the specific establishment that prepared it. While slaves did the majority of sustenance shopping, such commercial markings enabled their wealthy patrons to distinguish which ones they enjoyed at the dining table, instructing these illiterate servants to return to such shops in the future to assure continuing supply of the specific breads they liked. The use of the trademark or brand name on everyday consumer goods was established ahead of today’s use of distinguishing packing. This idea was a commercialized progression from the seals placed on large amounts of commodities to distinguish the lands and providers from which they originated. The merchant shops in the city were constructed using the agora template but with a unique addition. They were built as two-story units. The store was on the street level, while the second floor served as the shop owner and his family’s living quarters. This multipurpose housing unit, combining a commercial and residential venue, became the prototype for architectural city planning and was repeated for thousands of years across cities in western Europe. It later found its way in the late 1800s and early 1900s to the cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago when European immigrants came to the United States. Even today builders continue to construct intercity combinations featuring commercial establishments on the lower levels and an enlarged series of apartments and condominiums on the upper floors

In the modern commercial world, the emergence of similar retailing venues across borders, as well as the Internet, has created duplicate patterns of channels of trade where products are purchased through. From the American grocery Walmart to the French retailer Carrefour to the United Kingdom’s Tesco, these traditional brick-and-mortar retail chains have expanded their uniform merchandising platforms throughout the world. Franchises like McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken use similar business models and service systems to attract customers in different markets with little adjustments for local tastes in respect to menu items.

Beyond the creation of the exchange imperative, localized market and the subsequent construction of centralized grouped shopping areas to accommodate larger commercial requirements, the brick and mortar development, as occasioned by the trading initiative, had two other elements in antiquity. Storage facilities for grain and other required commodities were erected. They were first used to insure against famine due to natural disasters, then as collection points for governmental decreed taxation. They were later built at port cities to act as domestic surplus warehouses containing goods for export in support of the foreign trade activities of kingdoms and merchants. Such massive edifices were the first publicly constructed infrastructures along with roadways designed to bolster and sustain cross border trade.

The other major facility that directly owed its development to intercontinental commerce was the caravansary. The word originated in Persia and is a formation of the terms karvan (caravan) and sara (a palace or building) with sheltering fortifications. These were initially roadside inns where merchant traders could rest and recover from their argent daily journeys but they also serviced pilgrims and other travelers. Thousands of these facilities were built along the Silk Road and in cities to support the movement of commerce across the interconnecting networks of roadways moving from across Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East as well as Southeastern Europe. In his Guidebook to the Silk Road, written prior to the Black Plague of 1348, Baladucci Pegolotti, an Italian merchant, observed that the journey from Khanbalik (Beijing) to the Black Sea could take 300 days but advised his fellow travelers that the roadway was perfectly safe, whether by day or night, according to what the merchants said who used it. A contributing reason for the safe passage was the ability to spend nights in a caravansary. These commercial fortifications also became conduits for the flow of information and learning, furthering the flow of multicultural exchanges, a by-product of cross territorial commerce.

Many of them, built by Seljuk sultans and grandees to encourage and protect intercontinental traders, have retained their original physical properties, such as the walled conclave built on the Mediterranean Sea coast in Acre, Israel. Some like the Kürküü Han, the oldest caravansary in Istanbul, still function as a shopping arcade. The traditional caravansary was built like a box, a walled fortress with a single gate opening that allowed caravans of work animals laden with merchandise to enter and leave. An open interior courtyard was surrounded by gated chambers rented for individual merchant to board their animals, drivers, servants, and off-loaded commercial products. Some were of two-story construction with apartments on the top to allow traders to find respite from the road. The bottom storage bay was also used as a makeshift store allowing merchants to display and trade merchandise. Fresh water, food, and other amenities were provided at a price along with a money exchange and translations services to assist in exchange transactions with fellow travelers. Libraries offering both entertainment and educational value and even elaborate baths to allow for the travelers to rejuvenate and relax as well as perform ritual cleansing were placed in such facilities. It was at such establishments that news from distant lands was dispensed along with stories, ideas, and religious teachings. It was perhaps the first true multicultural cosmopolitan structure built on a commercial imperative. The caravansary system survived numerous political, military, religious, and economic calamities with many becoming the forerunners of villages, towns, and even cities that grew up around them. Palmyra in Syria was originally founded by a series of caravansaries as were other metropolis along the extended cross continental trade routes.

Toxic Nature of International Trade

The natural progression of the ancient exchange process evolving into a worldwide commercial system is not perfect. Like all secular human developed schemes, it is flawed. Notwithstanding the legal constraints imposed on global business institutions both nationally and internationally the questionable ethical actions of organizations involved in cross border trade is full of direct immoral injustices as well as indirect culpability. The spread of the Black Death or plague during two periods in world history was unswervingly traceable to the spread of international trade as merchant ships moved westward from India to the Arabian Peninsula and then Eastern Europe as well as easterly to China. While not an intentional act, the activities of global commerce predicated the events that devastated major populations around the world.

The ethical practices of multinational companies in the modern era of globalization garnered increased public attention beginning in the 1990s. The picture of a 12-year-old Pakistani child stitching Nike soccer balls and working the whole day for $0.90 released by Life magazine was a shocking example of depressed labor conditions in underdeveloped countries.14 Fostered by the unscrupulous associations of firms in their global supply chain associations the term “sweat shop” has become a universal sign of unethical conduct. The destruction of the Amazon rain forest as well as the harmful effects of other resource extraction industries on land and water around the world has called into question global commercial development. Environmental disasters like the 1989 Exxon Valdez tanker spill off the coast of Alaska to the 2010 oil rig leak in the Gulf of Mexico threatening the southeastern shorelines of the United States only serve to highlight the perhaps unscrupulous nature of business enterprises. The global financial crisis of 2009 is also a blot on the tarnished reputation of globalization, but its most offensive action was the international commercialization of the slave trade.

Slavery

Historically, however, the commercialization of the world was always beset with incidents of immoral turpitude on which the phrase “behind every great fortune lies a great crime,” as uttered by Honore de Balzac, may be based.15 With the exception of murder, slavery could be considered the most morally wicked action one person can do to another. But the practice of assigning property rights to a person and allowing them to be treated as chattel, and thereby exchangeable like a common commodity, is embedded in human history. The Bible, both the Old and New Testaments, recognizes the treatment of slaves, how hard you can work, no less beat, them and even when the owner can have sex with female slaves. While interpretive translations of such revered social religious guidelines use words like “servant,” “bondservant,” or “manservant” to mask or mitigate the concept of slavery, the ability to buy and sell them is approached with the same conditions of livestock and other valued products of the day. Leviticus 25:44–46 NLT advises that “you may treat your slaves as property, passing them on to your children as a permanent inheritance.” Ephesians 6:5–8 NLT admonishes “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with deep respect and fear. Serve them sincerely as you would serve Christ.” The Bible in Exodus 7–11 and 13:14 does however depict how God feels about racial slavery, noting the plagues he poured down on Egypt to release the Hebrew slaves. Both the Old and New Testaments condemn the practice of manstealing with the penalty written under the Mosaic law: “Anyone who kidnaps another and either sells him or still has him when he is caught must be put to death.”16 A similar consideration is directed at slave traders, as they are portrayed as “ungodly and sinful.”17

African Slave Trade

The idea of manstealing originated in Africa and is directly attributable to the commercial exploits of slave hunters who rounded up or sometimes traded for them with tribes who had acquired slaves during tribal warfare. The Portuguese began dealing for black slaves in the 15th century, purchasing them initially from Islamic traders who had established inland trading routes to the sub-Saharan region. Along with prized products like gold, ivory, salt, and other spices, the interior of Africa also provided for the opportunity to deal in human commodities. It was not until the 19th century that the international wholesale trade in slaves reached its zenith as occasioned by the need in the New World, the Western Hemisphere, to work on plantations and farms, and later silver mining operations. Slaves from the continent’s interior were forced to march hundreds of miles to the east coast to be resold and placed onto ships owned by Spanish, English, Dutch, and French slave merchants. Many perished on the land route with loss estimates of up to 40%, from the point of capture to arrival at these slave trading forts.18 With a figure of approximately 11,128,000 slaves delivered to the New World during the Atlantic slave trade,19 the number of captured African slaves (using a 40% casualty rate en route) would be as much as 23.5 million. This does not include those killed in the process of capture or who died during the sea voyage to the Americas, so the number of those caught in the international slavery trade may have been even higher. The dispersal of slaves shows the vast majority going to the West Indies (4.5 million), Central and South America (5.7 million). Only 500,000 or 4.5% of the total were delivered to British North America. It should also be noted that about 300,000 went to Europe.20 This massive shift in the population of the world, the wanton killing of human beings and the deplorable conditions of those who survived, is unmatched in history and attributable to globalization. The immoral stain of the international African slavery trade continues to plague the global commercial imperative, an atrocity that should always be remembered so it is never repeated.

Slavery in the Classical World

The ownership and trade of slaves was a common business venture in all parts of the ancient world. The population of the Greek city of Athens in 313 BC consisted of 84,000 citizens, 35,000 resident aliens, and over 400,000 slaves.21 A portrait of the Roman Empire at the end of the republic period around the 3rd century BCE indicates it was a slave-based economic society. Estimates indicate that the slave population just within Italy was 2 million, which would yield a 1:3 ratio of slave to free citizen.22 Slavery for Romans, and as with the Greeks before them, was a matter of citizenship with neither religion nor race factored into the determination. Qualification for slavery was being born outside the state, assuming the birth was not attributable to a domestic slave, whose offspring were automatically slaves. Upon capture, such individuals—considered barbarians, as they were not citizens—were considered booty, just like other possessions or property acquired by the victor in war. Prisoners provided the greatest resource and legitimate slave traders would often contract with military units for a set quantity at agreed-upon prices, extending their supply chain to distant lands. Many campaigns were paid for by the selling off of slaves, the spoils of war. It was possible for such potential slaves to buy their way to freedom. There was however no class distinction as the rich and poor were subject to slavery. Many of those captured were well educated and possessed skills and knowledge, which only contributed to their value when sold to new owners, thus fetching a much higher price on the auction block. Even slaves had discernable marketing differentiations. Slaves were promoted just like products for their unique attributes with their birth origins acting like a geographical trademark denoting they came with built-in skills found only in their specific birth land.

As abhorrent as the commercial slavery trade was it was also one of the primary contributors to the dispersal of knowledge in the ancient world as the slaves brought new ideas and techniques, even new inventions, to their master’s abodes. They were not just beasts of burden: Many slaves became governesses and tutors to the children of the master while others were secretaries or scribes in the household and business interests of the family. They imparted wisdom and information from around the world to the households they served in.

The business of slavery also came with caveats, just like those attached to all commercial transactions. Reputable dealers in slaves had a duty to provide buyers with a certification of the slave’s good health and criminal record. It was also their responsibility to attest that the sold slaves were in appropriate physical or intellectual condition for the buyers’ requirements and were not runaways—someone else’s property. Such conditional elements in the transaction were the beginning of product or service warranties—that is, items sold should be suitable for the purpose for which they were intended, a basic tenet found in today’s Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). In Roman society aediles—one of the board of magistrates in charge of public buildings, streets, markets, games, and other administrative duties—were appointed to oversee slave market transactions. Like special masters in law, they acted in a semijudicial manner to settle disputes between parties and to generally oversee that the sellers at slave auctions presented all the required certifications to the buyers and that the process was dispute free. The concept of business rental was introduced as collateral to the sale of slaves. The option of renting was available to those who wanted their services for a limited period of time (to assist with a harvest or to cover for an unwell slave). The public display of material wealth illustrated the social standing of Roman society just as it does today. The ownership of slaves was the most common way for a man to display his status and power with the elite maintaining a large cadre of slaves at their residences. It is reputed that Lucius Pedanius Secundus, a Roman politician in the 1st century CE under Emperor Claudius, kept over 400 slaves in his personal household. He was eventually killed by his slaves. Most slaves were utilized as field workers on the latifundia (large Italian commercial estates), which caused unemployment within the free Roman community and later contributed to the institution of land reform laws in the empire.

The economic value of slaves in the ancient world is well exemplified by the high percentages they occupied in the populations of Greece and Rome. The enormous transfer of slaves from Africa to initially promote and then sustain the economic growth of the New World is also a testament to their commercial importance. However, to quantify the impact of slavery, consider that in the mid-1800s the value of slaves in the United States was the single largest financial asset, worth over $3.5 billion in 1860 dollars—larger than the combined value of the country’s railroads, banks, factories, and ships.23 The cotton industry, solely dependent on slave labor, was America’s number one export and the financial fuel that drove the nation’s emerging capital markets. The Civil War, although influenced by arguments over states’ rights and driven by the clash of the industrialized North and the agrarian cultured South, had at its core a philosophical division over slavery, which is a human rights issue.

As business ventures moved around the world in both ancient and present times, the treatment of those who has encountered the commercial ventures of business institutions suffered. Many native populations in numerous areas of the world were and are still today pressed into the service of multinational enterprises whether by economic choice or necessity. Such remains a negative of the globalization phenomenon.