Reflections and Conclusions

Globalization has been, and will continue to be, a continuously evolving phenomenon. The trade merchants of the past had to react to the changes in the world as events around them propelled the growth and expansion of their commercial interests. Today, managers of business institutions must also deal with the observable fact that globalization, in the modern context, has “replaced the Cold War” as the prime international sociopolitical economic system and “is not a trend nor a fad.”1 Over the course of human history, however, as the process of globalization took root encompassing more and more of the world, the prodigy has always been driven by four prime components along with the fifth fueling factor:

- Market

- Cost

- Government

- Competition

- Technology

Market Driver

The market drivers of globalization consist of a variety of compelling considerations that combine to force commercialization beyond one’s borders. To offer for exchange those products and/or services to new customers in new territories—to expand market penetration—has its roots in antiquity, when a surplus of things emerged and one looked to get value for the extra inventory. Those products that exceeded normal usage in the domestic marketplace were offered in exchange for items found in other places and not at home. The vast storage houses of grain and other agricultural goods found in ancient Egypt, India, and Greece were all built near seaports as once the supply for their citizens was extracted the balance could easily be transported to trading vessels poised to move abroad. Even today the principle of selling off excess continues to be a motivator for the initial export process for firms entering the global arena. Much international trade business has been initiated by looking for buyers in new markets following a local market sales leveling or penetration plateau that resulted in not only overstocked inventory but also excess production capacity coupled with abundance of required local raw materials. The motivation behind the spice and incense trade would match up well with these points, especially with the profusion of the islands’ indigenous resources, which the rest of the world did not enjoy.

In modern times, the growing convergence of world consumers sharing homogenous needs and desires in respect to material goods and in some cases services has become a fast-moving initiator, encouraging firms to go global. This consideration, along with advertising spillover, coupled with Internet word of mouth, lets more and more people see what is new and different in the world thereby stimulating interest. Both these current examples are part of the market driver component of globalization but the idea has been around for centuries. In the ancient world, the common use and desire for olive oil and salt (as noted in Chapter 6 on early commodities) enabled such products to seek out new markets due to universal need satisfaction. With garments made from silk as a prime illustration, Marco Polo’s famous book on his travels along the Silk Road and into China served as a marketing tool enabling new societies to discover and in the end desire the exotic products other countries had to offer. His writing served as both an exciting travel brochure as well as a consumer inducement catalog, a precursor to today’s massive mailings prior to the Christmas season along with the flood of e-mails, Internet pop-up ads, and other advertisements on the World Wide Web. While the underlying catalyst for firms to venture overseas is to increase revenue the concepts developed during the formation of the roots of globalization are still in force today, pulling companies to globalize their operations. With the expansion of sales, firms also gain global economies of scale, a positive effect on cost reduction.

Cost Driver

The cost drivers of globalization pertain to the quest to obtain new, cheaper resources, be they materials or lower production costs, coupled with the gaining of knowledge or know-how that foreign markets offer. The overall desire is to permit commercial firms to increase their value efficiencies and lower costs. The cost drivers of globalization were first introduced in chapter 4 (on the age of exploration), with the search for new resources around the world reaching new pinnacles in the ancient world. Most of these ventures were of a dual nature. Primarily, these early European-led explorations were looking for a cheaper transport route coupled with a direct connection, to circumvent middlemen, to reach the valued resources of the east—a cost driver. Second, to locate gold and silver, the most valued and universally acceptable medium of exchange, the chief wealth determinate at such time by subjecting the local indigenous population to their rule and control (i.e., the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico and Peru). These duel, foreign, resource-based initiatives resulted in the establishment of overseas colonies by European nations begun during the age of discovery. While many ancient societies, including the Phoenicians and Greeks, created trading posts in foreign lands, their presence was not to possess these port enclaves but to insure and promote the cross territorial movement of goods, a market-driven activity. The period of colonization in the New World, the Americas, was a cost-driven impetus. Besides the initial stealing of gold and silver, the eventual mining of these minerals and the construction of vast plantations for harvesting of other natural agricultural resources drove the globalization initiative.

Modern companies have begun, like never before, to seek cost reductions by going abroad. Firms are offshoring in the pursuit of cheaper resources not just in material commodities but in human service abilities and skills. Just as their merchant ancestors traveled the world looking for new and valued things, today’s multinational corporations (MNCs) follow in their footsteps. But unlike the lands in ancient times that could merely offer cheaper raw materials and in some cases cheap slave labor, nations in the modern era induce firms to operate not only more cost efficiently but also with less-restrictive investment, legal, and tax entanglements that translate in the end into expenditure reductions—all contributing to cost as a globalization driver.

Competition Driver

Mankind has always competed with his fellow man for environmental resources to better their lives. In the ancient world the prime driver of early cross territorial trade expansion, the precursor of modern globalization, was the search for foreign resource-based inputs to sustain their civilizations. The first competitive drivers of globalization were the mechanics of everyday life that caused mankind to react and compete. After such a basic impetus, they resolved to go abroad, and then came the desire to locate and obtain new products to assist in making their societies better. In chapter 4 (on the age of discovery), the overriding economic policy called mercantilism drove nations to compete with each other and harbor their global connections for the benefit of the home country. Such a motivating desire still permeates our modern society as MNCs as opposed to countries still compete with each other to dominate their respective industries.

Today, commercial transactions, whether solely domestic or cross territorial in their operations, face foreign competition. Domestic firms are no longer insulated from competition from abroad and one method of defending one’s territorial turf is to take the battle to the commercial enemies land. For centuries The Art of War by Sun Tzu written in 500 BCE has been proclaimed as the prime treatise on winning strategy. His rules of warfare have been transferred to the business world in numerous texts as they provide strategies on defeating competition.2 Author Gerald A. Michaelson outlines principles with advice to generals (or in the commercial venue, CEOs) that upon being attacked at home (at their castles), rather than going on the defensive, they should send their operational troops from their local territory and attack the intruder in his own venue. In essence, they should bring the battle to the territories controlled by the invader, thereby forcing the domestic competitor to withdraw his invasion resources to defend his protected terrain. This preventive or defensive strategy promotes firms to go abroad.

A proactive initiative is also at work in the commercial competitive world. Domestic firms acting as suppliers for local firms must move offshore as their principles target new markets. Failure to follow their buyers not only results in a loss of potential revenue to foreign suppliers in the new territories but also may critically affect home operations, the as the newly encountered overseas become the global providers for MNCs including the original headquarters’ market.

A good example of the Sun Tzu strategic initiative can be found in an old artistic building trade. In ancient times, the unique skills of the art of masonry were never transferred out of the guilds they created to protect their craft. These specialized tradesmen moved from job to job, from one territory to ever-widening territories following the famous architects of the day. Such constant movement prohibited new artisans from entering the trade in foreign lands and in doing such prevented the rise of competition abroad. This specialized group could be considered the world’s first global worker’s union as a worldwide brotherhood or guild was created by these unique laborers. Not only did the masons exchange their guarded skills with their fellow freestone masons (or freemasons, named for the freestone—a kind of limestone that is relatively soft and easy to work with but then hardens with time and exposure to air), but their semisecret society became a conduit for knowledge collected from around the world. During the Crusades the vast wisdom of the Arab world, from a new mathematical system, to chemistry and medicine, to astronomy and navigation techniques found their way through the ranks of the Mason legion and then out to the rest of the globe’s population. What began as a commercial clustering of artisans to guard against competition and preserve their professional status emerged into one of the first worldwide federations whose members used their ever-expanding territorial work projects to accumulate new knowledge and pass it on to the world. Like the trade merchants of the ancient world that moved from territory to territory and across and between continents, the masons contributed to the exchange of ideas, invention, new process, and methods among the world thereby contributing to the growth of civilization on Earth, yet another societally beneficial by-product of the commercial imperative.

Government Driver

As noted in chapter 9, the partnering of commercial interest with governmental goals has always existed. In fact the first recognized publicly cross territorial merchants (per chapter 4) were dispatched by royal houses acting in the capacity of commercial ambassadors to set up trade associations with foreign nations. Even when private parties or those acting in unison sought out the right to transact business with foreign associates, they did so under privileges granted by the state. The right to do business in the overseas territories claimed by countries was also placed under governmental charter. Beyond such operating constraints nations have always been looked to regulate commercial transactions, beginning with their control of the scales to assure equal apportionment of the exchange of commodities to the enactment of specific laws and regulations.

While in the modern era the support of governmental structures in international trade is not as relevant as in ancient times, the comparative importance of social institutions to support the business initiative is still a driving force today. The legal framework created by governments throughout history has helped solidify the exchange process. Laws that regulate the transaction process have created a platform on which the commercialization of the world can be structured. In the modern era, governments have come together to promote and facilitate cross border trade. The mutual lowering of tariff and investment barriers via GATT and now the WTO by nations acting in concert with one another along with the privatization of the factors of production have enabled MNCs to expand and grow. The creation of regional trade associations from the European Economic Union (EU) to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as well as numerous other economic, cooperative, national accords around the world have created a borderless commercial if not economic mutual domain. Notwithstanding the absence of political unification, such geographical connections would rival in scope and scale the great intercontinental empires of Genghis Khan and the Romans. The shift in economic policies by governments to more open, capitalistic, and freer markets has created opportunities for international commercial venturing. The numerous universal protection conventions in respect to proprietary property as noted in chapter 9 have also created a joint pattern by nations around the world to foster the global commercial imperative.

Technology: The Fuel

Not knowing what to expect in alien lands, early man in his motivational adventures for new resources often carried with him supplies and tools used in the homeland along with the knowledge on how to use them. While they tried to get accustomed to the new surroundings, they found that the natives had the advantage of already being adapted, applying skills and techniques they did not have. Beyond exchanging just things, a more unique principle emerged as the two new groups meet. They could learn from each other.

While numerous individual societies around the world possess their own process of discovery and invention, the mutual sharing of such understandings laid the foundation for the exchange of technology, propelling globalization. New methods in the building of long-distance durable roadways, the emergence of more efficient modes of transport, coupled with advances in architectural design and construction as depicted in chapter 6 not only contributed to commercial globalization but also allowed civilization to improve and connect. The universal desire for new techniques and devices has always been fueled by the commercial imperative as the reward factor in business is the primary innovator of new technology. It provides not only the motivation but also the investment funds. Many sociologists and anthropologists like Lewis H. Morgan, Leslie White, and Gerhard Lenski have declared that technological progress is the primary factor driving the development of human civilization. Since the dawn of mankind’s emergence on Earth, he has always endeavored to advance and improve his life.

From the discovery of fire, the spear, bow and arrow, and pottery making in the prehistoric savage age; to the introduction of domestication of animals, agricultural husbandry, and metal working in the barbarian era; and on to the use of writing—all have propelled mankind forward. To advance technologically past our forefathers is a force that has always driven us. While many inventions were socially induced, the joining of the natural exchange imperative with the biological instinct to better one’s life was a dual motivator that produced and also allowed for dispersal of new innovative techniques and devices.

Technology was and still is the fuel of commercial globalization in regard to mankind’s ability to handle and control the environment around him, as well as his relationships with others in the exchange process. It consists of not only actual improvements but also the motivation to continue finding new ways and methods to improve life on Earth. Such a concept is central to the sustenance and growth of the world’s civilizations. The trading initiative was a developer of new advances (i.e., it directly contributed to its creation), while also a binary inducer of new innovations produced by mankind. It also provided the conduit through which new ideas, innovations, and inventions spread. Trade, therefore, was essentially a triple benefactor to the furtherance of civilizations.

In the process of filling the required needs of customers via valued and desired new products or providing more efficient and necessary services, private commercial institutions risk their own capital on research and development that in the end benefits and improves mankind’s lot. Business people throughout history provided the initiative and the funds to change the world. They became the instruments of change, displacing monarchs and governments as well as religious orders in the fostering of progressive innovation. On the pathways of ancient merchant routes, philosophies and religious teachings; inventions; and knowledge on improving agriculture and resource management, methods of architectural construction, and most of the life sciences were exchanged around the world. Short of war the commercial trade imperative is the greatest force of transformation across regions of the world. From clay tablets—which was first used to record exchange transactions and the precursor to the development of written languages—to using pigeons to send messages and to the modern fax machine, cell phone, and e-mails, the history of business-motivated communication has paralleled human progress. The commercial imperative has propelled the world forward, resulting in a shrunken world where all can literally reach out and touch each other electronically.

Combining such marvels with faster, more efficient transport devices allowed for a more seamless global supply chain network fueling the commercial engine of globalization and allowing the process to move at a pace the world had never experienced before. Goods from almost anywhere in the world can be loaded at the production site into containers and be tracked instantly as they move to their final consumer destination. Changes in consumers’ purchasing decisions are now automated to provide a constant check on their preferences, which in turn are used to adjust inventories and future production capabilities as well as raw material requirements. A true vertical and horizontal monitoring of the commercial process has been created that, when married to a constant, almost real-time communication system, can alert tactical decision making across and around the world.

Businesses have always demanded innovative attention to their profit needs with the result that the satisfaction they demanded also contributed to the beneficial use of such inventive devices for the world in general.

Another Set of Globalization Propellants

Authors Anil Gupta and Haiyan Wang, offering a dual inspection of China and India as strategic markets for MNCs to currently consider, utilize four stories (levels of evaluation) that build into a critical mass of motivational intent that should drive managers to enter these emerging markets.3 Their criteria are equally suitable as tools for analyzing the historic spread of globalization. Four areas for inspection are the following:

- Rapidly expanding megamarkets

- Cost-efficient platforms

- Innovative platforms

- Launching pads for new global corporations

Market Expansion

The growth of the megamarket is essentially the consumer driver, with more customers having uniform needs and desires. Ancient merchants took advantage of this factor by expanding their sales efforts beyond their limited domestic nucleus, pushing their circle of distribution further out to new territories as larger groups of consumers developed abroad in respect to their common desire for early commodities like olive oil, salt, and wine. This was further propelled by the desire for imported spices and reached new heights in the ancient world after the Marco Polo book, serving as a consumer bridge between East and West, introduced silk, porcelain, and other exotic treats to the European theater. The current development of consumerism in China and India is simply a constant repeat of the same market principle practiced before.

Resource Expansion

Placing production in more labor-efficient areas is a fundamental aspect of the cost driver of globalization. As practiced in ancient times, the concept was more centered on locating offshore natural resources and the specialized skills of native craftsmen that home markets did not have. The idea to seek out new venues of comparative advantage has driven and still drives the development of globalization in the modern age but the principle was birthed in antiquity.

New Ideas

Innovation, the constant striving for new beneficial techniques, is the technology driver and a factor that has always contributed to the growth of globalization. In the ancient world, it primarily consisted of new inventions in long-distance travel and navigation. In the modern world, it involves improvements in the digital informational and communicational age. Entrepreneurs not only have invented new products and brought them to market but also have been the prime inspiration and beneficiaries behind advancements in technology.

New Competitors

The emergence of new entities—national and private enterprises—in the worldwide commercial field has been a practice that has paralleled the development of both the old and the modern worlds. Competition from various emerging global arenas has always been a part of the globalization phenomenon. Chapters 3 and 4 well document the emergence at different times in history of national states and their chartered trading houses as well as independent merchants from all corners of the globe to take advantage of the opportunities of cross territorial trade.

Theoretical Reflections

Today beyond the exploration for additional sales markets and less expensive work forces to lower manufacturing costs, MNCs are in general taking advantage of the worldwide value chain and the pockets of excellence first really comparatively demonstrated and evidenced in Michael Porter’s The Competitive Advantage of Nations.4 The first chapter of his book is appropriately titled “The Need for a New Paradigm,” which implored companies to consider the competitive necessity to search the world for the best each country has to offer to achieve economic prosperity in their respective industries. The germination of this consideration originated with the simple basic premise that the most optimum utilization of natural and human resources can be achieved through the exchange process and its natural progression commercial trade. Early logic offered the idea that free trade could be advantageous for countries based on the sole concept of absolute advantages in production of things. Adam Smith, writing in The Wealth of Nations in 1776, admonished nations to consider that

if a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.5

The idea is simple. If one country can produce a specific set of goods at a lower cost than their neighbors, and if the foreign neighbor can produce some other set of goods at a lower cost than can be produced locally, then clearly it would be best for one to trade their relatively cheaper goods for the other. In this way, both countries may gain from trade.

The original idea was expanded and modified into the theory of comparative advantage in the early part of the 19th century and is often referred to today as the Ricardian model. The idea was first presented in an Essay on the External Corn Trade by Robert Torrens in 1815.6 David Ricardo formalized the principle using a compelling, yet objective, mathematical example that he wove into the context of his book of 1817 called On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. The concept then appeared again in James Mill’s Elements of Political Economy in 1821 and was featured as a key component in defining the composition of the world’s political economy with the publication of Principles of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill in 1848.

National Competitive Advantage in the Ancient World

Porter’s 1990 book was an in-depth examination of the principle that went beyond the originally limited criteria applying the cost of production or what he refers to as factor endowment. He broadened the prospective introducing four complementary and underlying influential determinants of national competitive advantage commonly referred to as Porter’s Diamond model:7

- Factor conditions. A nation’s relative positioning to others in the harboring of specialized or advanced input elements such as endowed natural resources, skilled, or artisan labor induced with knowledge and an infrastructure to deliver final products to consumers.

- Demand conditions. The nature, strength, and sophistication of home country consumer needs that drive an industry, pressuring it to improve. This is a quality issue and not a measurement of quantity sold in the domestic market.

- Related and supporting industries. The presence of collateral agencies that back up and sustain the prime industry.

- Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry. These are determined and influenced by governmental support and oversight.

When taken together, they compose elements of investigation that are used for strategic decision making in regard to the placement of firm activities in the best world geographical locations that afford MNCs the most efficient financial returns on investment. Although not officially recognized as such by ancient planners, such principles were taken into consideration as early merchants traveled from one area to the next appreciating but perhaps not fully contemplating Porter’s expanded approach to the basic comparative advantage theory in the selection of new areas of trade. To better understand and appreciate the use of the Porter Diamond approach in the economies of the ancient world, a review of the early products offered in chapter 6 is helpful. In antiquity the factor that element played the most important role supporting the notion that “the standard theory of trade rests on the factors of production” was natural endowment.8 Early trade was based on natural resource harvesting with environmental and climate the most important of the factor input conditions. The unique domestic artistic use of such resources also played a part.

The cultivation of olive oil, a prime commodity in the ancient world, created perhaps the first global industry but exhibited limited properties of the Porter Diamond model. The key factor endowments were dispersed across many of the Mediterranean coastal regions. Consumer demand, while strong, was even and widely dispersed with no country hosting a local advantage to drive the industry. The industry did not require related nor supporting industries and was not overly regulated by any regime. Hence no country possessed a relative competitive advantage according to the Porter model.

Salt, also profiled in the same chapter, was in some instances an imported prized commodity exchanged for gold, as some regions did not possess the necessary mineral deposits or did not have the technology to extract it from the seawater. Hence factor conditions did play a greater role in the industry then in olive oil production. Consumer demand was again evenly dispersed around the world with marginal effect as a determinant of national competitive advantage as with olive oil. Few or no supporting industries contributed to its sustenance with the exception of trade routes developed to reach other markets. No overt governmental oversight, except in China where its products were controlled by royal decree, impacted the industry. The industry was, therefore, marginally characterized by the Porter criteria.

On the other hand, the early trade in spices as recalled in chapter 6 was a good example of Porter’s Diamond model at work in the ancient world. The factors of production and environmental conditions were paramount to the agricultural harvesting of the spices; they were tied to the lands in India and the so-called Spice Islands due to indigenous plants and centuries of cultivation. Consumerism, while not localized, was extremely high and centralized in a wealthy sophisticated foreign clientele who demand the best the region had to offer. The social infrastructure of the lands producing the spices contributed to and actively sustained the industry as the native population was geared to its harvesting and export. In addition, the region was commercialized by knowledgeable merchants who organized a narrow, funnel-like, monopolistic distribution network stretching halfway across the globe that strongly supported the spice trade. While the tribal social order (the government on the islands) did not take an overly regulatory part in the industry, the norms of group behavior orchestrated in the tribal system allowed for a uniform maintenance of the social structure and a well-balanced collective rivalry that sustained the industry. Taken together, the spice trade illustrates many of the key determinants for the development of a regional competitive advantage.

The silk trade may be the prime and therefore the best example of the Porter Diamond model at work in the ancient world. The rare silkworm is indigenous to China, which possessed a natural conducive environment for its habitation and reproduction. The cultivation of the valued material taken from the cocoons and the skill required to extract the fibers making up the pouch comprise a specialized technology held by Chinese workers. The continuous domestic demand was very strong due to its segmentation among the royal house and extremely wealthy patrons that were separated from the masses in a predominant class society. The power of the buyer coupled with their high sophistication required never-ending excellence from the industry. Failure to please the empire’s court could even be considered an offense and merit a punishment. The industry was organized along strict supportive functions with the weaving and dyeing of the cocoon strains only available in the country. The sewing of the fabric into elegant garments with unique and distinctive patterns was an art with the necessary skills harbored in China. The government in the form of royal decrees forbade the exportation of the silkworms and the knowledge inherent in the industry abroad. Laws prohibiting such export were strictly enforced with severe punishment. All foreign trade of silk products was under strict control with distribution in the hands of government-appointed agents. Alien buyers of the materials were approved yearly and operated under license. All the determinants of national competitive advantage were satisfied in the silk industry and the country was assured a global monopoly of the trade.

The Porter Diamond model offers determinable patterns of industry success via the identification of clustering in which related groups of similar firms and industries emerge in one nation to gain leading positions in the world market. One could reasonably question if the analysis in respect to the competitive advantage of nations is a more appropriate strategic evaluation model of globalization determinations in the ancient world and up through the mid-1980s as opposed to modern times. The centralized nature of the Diamond approach to identify a single, most competitive nation for a particular industry to be placed in may not be germane in the highly decentralized world of today. The exhaustive and comprehensive research in his book published in 1999 spans the period from 1960 to 1987, a total of 27 years. But in the last 23 years the world has dramatically changed. The strategic shift to offshore labor to emerging nations for more cost-efficient means of production and the collateral use of outsourcing for services and other value enhancing primary and support activities in areas that contain the specified skills that MNCs traditionally harbored in their home office are not included in the analysis. A review of the determinants could support this contention.

Today, factor conditions (the quest for inputs to a business enterprise) are segmented and not dependent on a particular nation to provide all the components. The modern extreme global value chain, coupled with advancements in technology to tie it all together into a seamless organized structure, has divided the world into pockets of excellence. MNCs are free to roam the world and place their value-producing activities in a series of countries as opposed to putting all their operational eggs in one national basket. They can divide the globe, crisscrossing numerous nations in their quest for the most suitable locations for raw materials, efficient low-cost production, advantageous marketing expertise, and purchasing, assistance as well as logistical support. Even in use of research and development (R&D) teams they can comb the world for the most knowledgeable centers and link their combined efforts if necessary. They can also choose from a variety of national sources for capital while determining a valuable headquarters site that gives them virtual control, administration and taxation advantages. All these considerations contribute to modern globalization.

The demand condition that historically placed companies in a market where the sophisticated strength of indigenous consumers pressured constant improvement tends to be a moot issue as universal consumerism driven by the homogenous needs and desires of similar users around the world negated such criteria. Globally recognized branding and trademarks have today replaced the traditional “made-in” designation and more and more quality is attached to name recognition and not the place of production.

The need to place a business in a country where related and supporting industries are concentrated, which thereby provide assistance in sustaining and driving the prime industry, has been fractured by the extreme global value chain and by the persistent and growing use of alliances around the world. Even competitors are joining to form strategic alliances that benefit each other. The collateral industries that once were necessary as local feeding stations to keep an industry alive in a particular country are now scattered around the world. The use of offshore contracted labor, both in the manufacturing and service industries traditionally centered in the home country, is today commonplace. With certain industries being afforded greater latitude in some nations in regard to regulatory oversight, foreign ownership rights and freedom of exchange and profit—capital movement over others—companies are freer than ever to compare and choose those countries that offer them the best deal. Rivalry in almost all industries is today truly global in scope and scale as opposed to concentrated in one particular country.

While some vestiges inherent in the ancient and the post-1990 tradition world of globalization still exist for some industries and therefore are validly susceptible to Porter’s Diamond analysis, the model of competitive advantage of nations for all business venturing in the future may not be based on this historic and important research. National competitive advantage in the coming modern age of globalization may not be industry specific as Porter’s criteria imply but rather it is more relevant to the individual primary and support activities, the areas of measurable value input that are today decentralized around the world and not placed in specific nations.

The Porter model to determine the comparative advantage of nations in certain industries is therefore subject to a paradigm shift. The determinable criteria employed to screen and evaluate countries beneficial to the location of a given industry with their territorial borders is not as relevant today (due to globalization) as when its results were presented in the late 1990s. No reference in the Porter index is made to China or India no less any emerging (than called developing) countries. As previously mentioned the use of one or a series of integrated offshoring or outsourcing centers for specialized activities or value inputs to enhance or even sustain the comparative advantage of firms operating in a selected industry was not part of the survey conducted nor the subsequent evaluation and hence model presented. The analytical method illustrated in the original model is relevant to the two early eras of globalization, ancient trade and the age of discovery, when firms began to span the globe looking for suitable locations for their entire operational base based primarily on territorial resource allocation, cheap labor and local governmental assistance; factors that now may be static and temporary. Today the definition of modern globalization is indicative of a period when value-creating activities are not centralized in a singular nation but divided or segmented into a linked chain of collaterally related supporting elements that contribute collectively to the accomplishment of firm goals. The new strategy is to utilize far-flung clusters of excellence, an idea later presented by Porter in 1998. Such global clusters are defined by Porter as an “array of interlinked industries and other entities important to competition,” represented in “geographical concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field.”9 They include suppliers of specialized inputs from labor to components to services while extending to logistics, channels of distribution, and firms related by skill and technologies. Also included are governments, institutions, and associations providing specialized support. The global system is truly multinational as it is created by an array of cross-disciplinary and supportive interaction, which when used together drives innovation and results in efficient productivity; and as such, is the essence of modern globalization.

Industrial Competition in Ancient Trade

Even the techniques for analyzing industries and competitors to device strategy using the ideas presented by Michael Porter’s analytical model normally referred to as the five forces of competition10 can be applied to ancient trade in specific industries. The forces are composed of the following:

- Potential entrants. The threat of new competitors into the industry as determined or measured by the barriers to entry or the required start-up resources.

- Bargaining power of suppliers. The ability of providers of inputs to exert monopolistic holds on the standardized inputs necessary for firms to compete successfully in the industry. It is also influenced by the concentration and number of suppliers in an industry.

- Bargaining power of buyers. The relative strength of customers to exert pressure on the industry. Also influenced by the concentration and number of purchasers.

- The threat of substitute products or services in the industry.

- The extent of the rivalry among industry competitors.

In ancient times, the players or competitors were in reality nations or kingdoms using limited private institutions to accomplish their economic ends. While they competed to a degree in what could be then be labeled industries, as many were just local trades, their gradual expansion across territories began the roots of modern global competition. However the emergence of the spice and silk trades reviewed earlier presents good examples of strategic decision making on a global field although this was not really appreciated by the commercial merchants of old.

The threat of new competitors were limited in both the spice and silk industries. The compressed and narrow distribution network on shipments from the spice islands through the Indian sea routes on through the South Arabia land mass and to northern Mediterranean Europe provided a virtual monopoly for the middlemen traders involved. Indian captains closely guarded their secret of monsoon aided transit across the Indian Ocean. Arab merchants, using their tribal heritage links like the Nabateans who created the city of Petra as previously presented, did not allow outsiders to replace them in the spice distribution chain. Even at the consumer level, local wholesalers used valued upstream contacts to secure their precious allotments and sold downstream to exclusive shop and bazaars that dealt only with a selected higher clientele, the wealthy landed gentry. The entire distribution channel was a closed system allowing a few choice entrants, who were already close associates of the existing players. Entrance to this unique commercial club was severely limited. The competitors in the industry tended to split the trade monopoly in their operational areas and all were content to have their fixed or prearranged portion. Little rivalry was, therefore, evident as there was enough profit to go around. The threat of substitute products was almost nonevident as the individual spices themselves could not be duplicated anywhere else. The bargaining power of suppliers really did not play into the industry as the spices were produced by numerous independent tribal growers. all happy to sell their harvest. The bargaining power of buyers on the industry was also minimal as they took all the spices they could get their hands on with the consumer appetite only growing. A competitive evaluation utilizing the five forces of inspection indicates that a strategic positioning in the spice trade was worthwhile for ingrained participants. While competitors in the industry could not avail themselves of Porter’s 20th-century analytical approach, they nevertheless reaped the reward—wealth accumulation, which is the same goal that modern firms would pursue as they used this industry evaluation model. No wonder European nations undertook at great expense in the age of discovery the finding of alternative routes to the treasures of the East. Entrance into this exclusive industry was costly and only governments could afford the required dues. The ancient merchants in this trade while perhaps not understanding the Porter model used its principles well.

The silk trade would also match up well with spices as the industry to be involved in during ancient times. Potential entrants would need to run the gamut of establishing organized caravans across 3,000-plus miles of dangerous travel while mastering the cultural and political differences along the way. They would need an initial sizable investment in goods that could be traded along the initial outposts on the eastern outbound journey. To insure safe and effective passage they would have to be granted a chartered right to trade with the Chinese royal emissaries at the other end who controlled silk export. Getting into the silk business was difficult, preventing most entrants to even consider it. The benefits of the silk trade, the enormous markups at the wholesale and consumer levels made for a most attractive profit initiative and a testament to the negative power of buyers to exert downward pricing pressure on the industry. Just like spice the appeal of this exotic foreign material with consumers made for a growth industry. The suppliers to the industry were not independent as they were already integrated into the core and could not exert any undue power. While the whole industry on the Chinese side was under the direct control and administration of the royal court, they had the ability to affect the industry but their desire to extract revenue for the empire’s treasury limited their ability to pressure the Western traders that they needed. It should be noted that Chinese merchants did not travel abroad to sell silk or any domestic goods, so the foreign traders had to be welcomed and not taken undue advantage of, or they would lose the valuable service they provided the empire with. So rare and so exquisite were silk garments found in China that finding a substitute product or even having the fabric made somewhere else was not a threat.

While there was rivalry among the existing silk garment makers for the affection of the royal court to favor their creations, the competition for the global trade was severely limited, as it was under the province of the emperor’s export agents. Industry competition at the global level was really in the middleman merchant arena and while rivalries existed most were friendly struggles as they all shared common commercial challenges: the harsh voyages from West to East and back again and the Chinese monopoly of the silk trade. Porter’s reflective analysis of the silk trade would show it to be a most lucrative industry to compete as an established player during ancient times, a strategic positioning that the ancient merchants new well without the advantage of this modern evaluation model.

Porter’s five forces of competition in industries continues to be relevant in modern times and perhaps even more so in the future, as the competition of MNCs historically placed in the economic triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan has today expanded with the emerging nations of China, India, and Brazil as well as others producing new global directed companies. More firms from more countries than ever before, as noted in the prologue of this text, have joined to push for commercial opportunities and hence the threat level of new entrants has dramatically risen. Playing the global strategic game has gotten more complicated and more diverse with new players able to enter the worldwide playing field. The existing participants will be pressured to take a wider global view and they will need to be ever vigilant in the exercise of their judgments in the future just as early governments and public enterprises did in the past. The age of discovery is about to be replaced by the age of competition—with the same goals, just different game rules and more players converging on an ever-widening field.

Mankind’s Desire to Trade Revisited

Mankind’s inherent desire to trade is vividly portrayed in the opening scene of the film Apocalypto, a fictional depiction of Mayan times and their culture.11 A band of village tribesmen are hunting in the forest when they come across an unfamiliar group fleeing from some unknown terror. The leader of this strange native group seeks permission to cross their territorial land and offers tribute in the form of mysterious fish and plants for the privilege, which is granted. Such a transaction conducted with gestures and accompanied by languages unknown to the movie audience well exemplifies a principle rooted in the cultural anthropology of almost every society around the world—the exchange imperative. The symbolic offerings by one to another as they encountered new groups across alien territories is repeated throughout history and is the foundation for modern-day globalization. It is one of the prime roots on which civilization developed. For those that do not see it in such broadly painted strokes, it is at least its chief nourishing agent. The commercial branches produced by the roots of the ancient trading process have culminated over time into today’s transnational business system.

The Stepping-Stones of International Trade

In ancient times, trade between geographically noncontingent territories moved through a system of interlocking transactions. On a direct state-to-state basis, countries in ancient times carried on trade across their borders. For example Egypt received the exotic treasures of central Africa by initiating trade relations with the nation of Punt which acted as a middleman between Egypt in the north and a series of tribal African supply venues in the continent’s interior. However in the case of private merchant trade, numerous individual and independent middleman transactions took place, forming an indirect patchwork of intercontinental trade that helped weave the tapestry of early globalization. As eloquently exemplified in Henry Yule’s Cathay and the Way Thither,12 a traveling caravan might leave Jordan loaded with local resources, trading them at each part of the journey for those of another location and then proceed onward, hopefully making a profit each time. Upon reaching Cathay through the Silk Road, it finally reversed direction back to the West where it would continuously engage again in separate exchanges, returning home with a cumulative return on its original investment in domestic goods first collected in Jordan months and even years earlier. Along the way, merchants would frequently have changed travel guides and locally hired guns to ward off attacks from bandits. Their mode of caravan transport changed from camels to horses to donkeys, and they even changed the intermediary forms of exchange to suit separate areas he moved across and to suit the products he continued to purchase or barter for. Merchants needed to deal with not only other merchants but regional governmental administrators and roving bands of thieves. The commercial skills of such men were truly remarkable with amazing cross-cultural negotiation abilities. They were daring explorers with a taste for adventure and they were risk-taking business entrepreneurs. Today managers of multinational enterprises possess the same spirit ingrained in these first global commercial pioneers. They continue to encounter many of the same obstacles their forefathers experienced. In modern times, global business still passes through the multicultural layers of varying cross societies while encountering varying governmental regulations as they piece together the advantages of the extreme global value chain. The ability to filter them and unite them is a skill set that modern managers must still hope to attain as they emulate many of the characteristics of their merchant ancestors. As mentioned earlier in the book, to trade, from the Anglo-Saxon root word “trod,” means to walk in the footsteps of others that went before. Surely this is the path that today’s global managers take and the roots of globalization continue to act as a valid initial pathway.

The Role of Businessmen

A review of the roots of globalization and the commercial imperative finds the role of businessmen in the development of civilization a most influential factor. As players in the natural extension of the exchange process, they have emerged over time—alongside government systems and religious orders—as prime agents of social growth. They were the first explorers of new territories, the first foreign travelers, and as such cross-cultural ambassadors. They served as human instruments of change, bringing new ideas with them, sharing them with others, and in return bringing back to their homelands the innovative ways found in distant lands. They spread customs, religious teachings, and technological improvements across the globe. Their activities initiated the introduction of sovereign direct taxation, tariffs, along with payments of numerous other fees that funded royal and later national treasuries. While the revenues generated from commercial ventures contributed to the war chests of rulers, it also helped to finance the construction of public infrastructures to benefit society. They contributed to the founding of spiritual houses of worship, often combining with the Church and government in their overseas actions to alter the social development of nations. The needs of business helped spark inventions in various scientific fields, especially communication, transportation, and navigation. It was the commercial inspiration that drove the creation of numerous devices and systems aimed at bettering people’s lives.

The exploits of merchants were not without moral outrage, as their global search for resources and labor resulted in the oppression and forced dispersal of minorities around the world. They took undue advantage of their monetary power to suppress and alter the lives of many, which often accompanied colonization by their national governments to control the destinies of the populations of occupied lands. While they were perhaps the first beneficiaries of foreign conquest, they also helped to establish civility and stability in war-torn territories often to the detriment of the inhabitants. Like the other social institutions mankind has created to manage the lives of others, they also provided societal opportunities as well as constraints.

The natural stratification of societies placed entrepreneurs in a distinct class in every culture, some revered and others chastised. In some societies they attained a level just below that of the elite noble gentry and in doing so became a link between rich and poor, a new class we today refer to as the middle. The craft trade guilds they patronized became a new social force while the transition they orchestrated from agriculture to industrialization was instrumental in altering the life styles of working populations.

The heritage of the ancient merchant is visited on the modern-day equivalents: the multinational corporations and their legions of global managers. The actions of this new group continue to impact the world just as their forefathers did, and in fact perhaps to a greater degree and scale in the modern era of globalization. The influence on the world’s social stage of the commercial imperative in the past, present, and in the future cannot be overlooked nor minimized. Merchants were and continue to be not only engines of world economic development but also contributors to the growth of civilization on Earth. Little has changed since the process of exchange yielding the first businessman. Today’s practitioners of the global commercial arts share a common legacy with those that went before them.

Final Thoughts

While the term “globalization” tends to be associated with a current period that is beset with conflicting viewpoints and therefore contradicting indications of equal value for the world’s population, the overture to the idea of interlinked nations tied together by cross border trade began in ancient times. It evolved out of a common shared instinctive international heritage of all civilizations, no matter where they developed, to reach out to alien territories. And in the process, to exchange things and ideas. It is therefore hard to condemn the principle that originated with our ancestors from every world compass point. In search of enlightened intelligence, they strove to discover new lands and prize the attributes of global trade.

Trade as a Disincentive to War

The cartoon in Figure 10.1 illustrates the prime reason for conflict between people—the invasion of another’s land for their resources. While ancient rulers, and even modern-day national leaders have used external warfare for the propaganda value of military success to promote national pride, the securing of new territorial riches has always carried a lucrative economic benefit to the victor.

It can also be used to exemplify the opposite principle: If people traded as opposed to making war to receive the bounty that the inhabitants of another territory produces then perhaps such man-made conflicts might end. A limited example is Western Europe where countries were almost constantly at war before 1945, but in modern times with the formation of the European Economic Union (EU, successor to the 1950 six-country formation of the European Economic Community), a period of peace has been maintained in the region.

Economic Imperative for War

Reprinted with permission of John L. Hart FLP, copyright 2011.

In January 2001, Havard Hegre presented a paper titled “Trade as a War Deterrent”13 in which he devised a model to show how increased trade between two states may make war between them less probable. The theory is based on the conjecture that reciprocal equal dependency renders war irrelevant and fair trade constrains armed conflict. The urban myth attributed to Thomas L. Friedman that “no two countries that both have a McDonalds have ever gone to war”14 could be the slang interpretation of Hegre’s proposition. Even if Hegre’s model is complicated and open to attack and the McDonald’s reference a contrite ad-lib on reality, the model at its core has a simple notion for one to ponder. If two parties have what each other desires and a fair, equitable exchange can be made, why would one risk a fight, injury, or loss when a simple trade will do? It seems like we are back to ancient barter as a deterrent to human hostility and a contributor to a more civilized world. We should remember where this idea has taken us to today—the era of contemporary globalization.

Hostilities Do Not Always Impede Trade

While the concept of trade as a deterrent to war is interesting, conflicts over territorial trade rights in ancient times historically led to hostilities from the Trojan War to the Punic Wars (Rome verses Carthage over who would rule the Mediterranean) as well as a host of other armed disputes across the globe. However, a recent interesting archeological finding has led to equally intriguing observation as to the role of trade in diminishing hostilities even among warring factions.

Naucratis, a Greek trading emporium in Egypt that existed during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, has long baffled anthropologists and sociologists. This immigrant-dominated commercial conclave was composed of Greek citizens who are themselves hailed from among the then several Greek nation-states that were themselves at war. Yet in this distant land they lived peacefully and in harmony.

How these “inhabitants managed to operate on foreign soil and create a new sense of common identity” in “a trade settlement in Egypt under the protection of powerful Eastern empires”15 is an inquiry worthy of consideration. Dr. Alexander Fantalkin of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archeology explains that Eastern Greece at such time was controlled by the powerful Lydian Empire (Turkey), and as such, the Greeks were required to operate commercially under their regime and pay tribute to such overlords. When Naucratis was established Lydia had a formal political alliance with the Egyptian royal house. Greek businessmen used such an association to establish, as Greek representatives of the Lydian government, a trade settlement using a rather astute commercial venturing shield on two fronts. First, they made the best of a repressive regime back home to further their foreign trading opportunities; and second, they got around their own domestic interstate rivalries. Fantalkin calls such a unique global economic approach an instance of “contact zones” in antiquity:16 the ability to pursue offshore business commercialization in spite of foreign entanglements between the home lands of the parties seeking associations, a kind of a neutral site, perhaps akin to Switzerland during World Wars I and II and Hong Kong prior to the quasi-capitalistic opening of communist China.

This example in history is important as its shows how warring factions, in this case adversarial Greeks, finding a common interest in trade, could overcome homegrown hostilities and create instead a brotherhood of merchants in another territory. They even used an oppressive adversary as an edge to further their own commercial interests. The opportunity to trade may trump political and social disharmony with war just another barrier to overcome in the process.

World Economy: Back to the Future?

Even for economic historians it is difficult to investigate and analyze, no less statistically codify, the exact structuring of the global economy and the relative positioning of nation-states in the ancient world. However, in Getting China and India Right: Strategies for Leveraging the World’s Fastest Growing Economies for Global Advantage, the authors look back 1,000 years in an attempt to measure the changes in globalization gross domestic product (GDP) by country and show, by the “standards of the times,” the leading centers of economic prominence, and the shift in dominance over such a period.17 The authors present a chart of the percentage of world GDP achieved by the U.S. and other western offshoots, Europe, China and India from 1000 to 1950.18 It shows that for over 800 years, 1000 to 1820 China and India together accounted for almost 54% of the world’s GDP. The swing to other regions of the world in the 19th century is attributable to the Western industrial revolution coupled with the internal weakness of China and India, allowing for the dominance of colonial powers that stymied their continued internal growth as well as independent foreign trading opportunities.

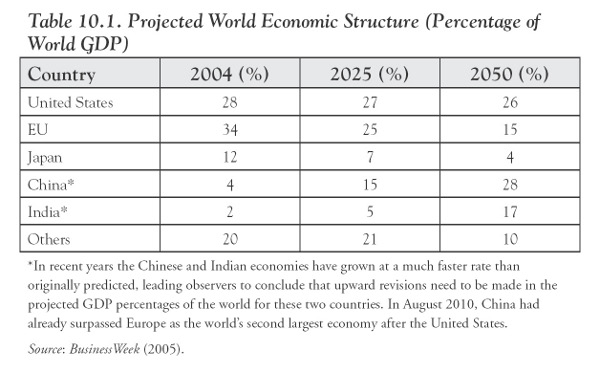

Perhaps the next 50 or fewer years we will see a rotation on the world GDP national degree wheel (a pie chart illustrating China and India taking a larger share of the pie), with a reemergence of China and India and hence a new adjusted realignment of the global economy. Projections into the future (Table 10.1) reveal that while it took centuries for a dramatic shift in global economic dominance to occur, today’s modern MNC’s globalization imperative, driven by governmental directional adjustments and fueled by technology, may allow for a faster shifting of leading country players:

As the world has grown economically, it has changed and future predictions seem to indicate that it will revert to its original roots and the main trunk of its growth: East-West trade.

In Why the West Rules—For Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future, a historical investigation into the balance of power in the world, author Ian Morris opens his book by postulating a fictional account of England’s Queen Victoria subjecting herself to the rule of the Chinese Emperor Daoguang in 1848.19

This fictional account is used to dramatically introduce the reader to the differences in globalization and how economic development affects world history and, perhaps, what it can reveal about the future. The reason given for the West’s domination of the world is that sometime around 1750 European entrepreneurs, led by the English, harnessed the power of steam and coal, ushering in the Industrial Revolution and propelling their rise to power in the 19th century. The opium wars arising out of the triad of trade as opium was exchanged for sliver and silver for tea created a global economic force that subjected China (and India indirectly) to foreign rule. Led by the government-backed British East India Company, South Asia became their private commercial fiefdom. In short, the shift in global political power for the last 250 years via the globalization of the world was economically tilted toward the West. Such supremacy can be traced to the reluctance of China, India, and even Japan, before American Admiral Perry forced open their harbors, to not only unlock their respective territories but actively seek out foreign trading activities. If the original Star fleet of the Chinese Admiral Zheng in 1421 had been allowed to continue their efforts after their ill-fated return and rejection by the Chinese Imperial Court, today’s world would have been very different and the factious account of England’s surrender to Chinese rule, following that of Europe, might be correct. As noted in chapter 3, the Chinese armada of close to three hundred ships was far more advanced in map design, navigation techniques (such as the magnetic compass), advanced rudders, watertight compartments, and elaborate signaling devices. Along with 27,000 sailors were 180 doctors and pharmacists, in contrast with Christopher Columbus and his 3-ship contingent of 90 men that sailed in 1492 from Spain.20 The ability of China in the 15th century to dominate the world and appear as the most advanced civilization at that time has been well documented but its reluctance to pursue and engage the outside world via trade has historically plagued this magnificent society. A number of explanations ranging from cultural and geographical to political have been offered along with the overriding fear of alien contamination. However, the historic economic mind-set of China, supposedly voiced in 1793 by Emperor Ch’ien-Lung in response to a British trade delegation, may sum up the Chinese view and provide an insight into their thinking: “Our Celestial Kingdom possesses all things in abundance and wants for nothing within its frontiers. Hence there is no need to bring in the wares of barbarians to exchange for our own products.”21

Such proud arrogance may have permeated the thinking in 1423 when the aforementioned Star Fleet returned and China virtually locked its borders from alien influence. While an opportunity was missed at that time China is now poised to regain its once wasted sophisticated supremacy. The historical and future path of Asia is best summarized by Victor Mallet:

The debate about whether Asia will once again dominate the global economy—as it did for two millennia before the industrial revolution in 18th century Britain and the rise of the US—is over. The 21st century will be the age of Asia’s return to economic pre-eminence.22

Scholars have suggested that more than half of the basic inventions and discoveries on which the modern world is based originated in China. A list of the innovations—from the wheat shaft separator, saddle stirrups, compass, water clock, abacus calculator (capable of figuring the decimal system and the value of pi), moveable type, seismograph, parachute, rudder, mast, cartography, and gun powder just to name a few—were developed centuries before they made their way into Western society. They were carried abroad by commercial tradesmen and merchant seamen visiting their market. By looking backward does one attain the ability to understand and appreciate the future?

Concluding Points

Globalization is not a specific event in time, it is a culmination of the wonders of difference and discovery that our ancestors recognized thousands of years ago. It is a modern-day echo first produced by ancient trade. Exchange with others gave man the opportunity to expand and grow.

Therefore, globalization is merely the natural progression begun in ancient times as an ingrained social custom. It is a force of natural civilized order that continues today. How the current generation uses this legacy is open to debate. The eminent scholar John H. Dunning acquainting modern globalization with entrepreneurship and free enterprise reminds us that “capitalism is a better instrument for the creation of wealth that it is for the equitable distribution of its benefits.”23 He reminds us that we must also be ever vigilant as to how such inheritance is used.

Let us not forget, however, that cross border trading opened the world to innovations and progress while increasing performance standards—today known by the terms “global benchmarking” or “world class.” World trade enabled humanity to grow, to come together, and integrate their lives and learn from each other. It was the midwife for civilization as contributed to by all cultures at different periods in their own history. Let us embrace the concept, as it is the one true common heritage that the world shares. It is developed everywhere. No nation has a patent on its creation; it belongs to all of us, and it is a fulcrum on which the world society developed and is still perched today. Through trade cultural diffusion occurred, although the process is selective, anthropologists generally agree that as much as 90% of all things, ideas and behavioral patterns—from religious orders to sociopolitical economic systems to inventions found in any society—have their origins in other cultures.24

This phenomenon called globalization is not to be measured nor classified as good or bad but merely understood. Such instructional knowledge begins with an inspection into its roots. Educational instruction offered to all business students necessitates an exposure to the ancient trading pillars on which the current world is constructed. Not to allow such examination is to rob students of an appreciation of the richness of the commercial imperative they inherit today and the importance of their continuing influence and contribution to the development of civilization on Earth.

Globalization does not necessarily promote new vocational gains or wealth creation in all the people it touches. It both gives and takes. Inherent in the man-made process is the possibility that it can either uplift or depress certain segments of the world population by providing opportunities for some while also taking advantage of others. As Dunning rightfully points out, “Globalization is a morally neural concept. In itself it is neither good nor bad, but it may be motivated for good or bad reasons, and used to bring about more or less good or bad results.”25

But the one unarguable thing about the exchange process, from ancient times until today, is that it causes one to form new relationships with foreign groups. The more we interact with each other the more knowledge we gain abut others. With such new insights, the less we have to fear of alien things and the more tolerant of difference we become. This is the true gift of globalization to humanity and its chief contribution to civilization. Perhaps Dunning best defines globalization in its expanded sociopolitical and economic role throughout the ages when he states, “By globalization, I mean the connectivity of individuals and institutions across the globe, or at least most of it.”26

Globalization, despite the modern interpretation of the phenomenon as a technological communication device as depicted in Figure 10.2, is much more. Its roots are firmly planned in antiquity as the process of exchange is fertilized by mankind’s natural affinity to reach out and touch others. It has always existed and always will. The only change throughout history is its influential degree and scale in regard to life on Earth.

Modern Portrayal of Globalization

Reprinted with permission of John L. Hart FLP copyright 2011.