Chapter 5

Developing the Training Program

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Creating a supportive learning environment

Creating a supportive learning environment

![]() Designing materials to ensure that learning occurs

Designing materials to ensure that learning occurs

![]() Examining the pros and cons of presenting information

Examining the pros and cons of presenting information

![]() Identifying a variety of activities

Identifying a variety of activities

![]() Designing for inclusivity

Designing for inclusivity

![]() Considering the purpose for using visuals

Considering the purpose for using visuals

![]() Wrapping up an effective training session

Wrapping up an effective training session

Training is serious business. Or is it?

Educators know that children learn from play. Adults do, too. This chapter addresses the design and development of training. Although the design and development of a training program is a lot of work, you should remember throughout to ensure that the design creates training that is learner focused. That is, the participant learns all the KSAs (knowledge, skills, attitudes —remember? See Chapter 2) while enjoying the process along the way.

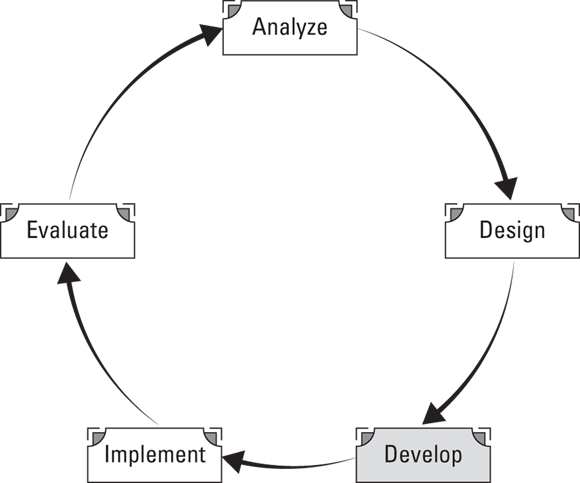

This chapter discusses the third stage of the Training Cycle: Develop (see Figure 5-1). The training you develop is built on a foundation formed by two important aspects: adult learning principles and the learning objectives.

- The adult learning principles, developed by Malcolm Knowles and discussed in Chapter 2, are the basic characteristics that distinguish adult learning from how children learn.

- The learning objectives, created as a result of the needs assessment and analysis, are discussed in Chapter 4. These objectives describe what the participant will know or do as a result of the training.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-1: Stage III of The Training Cycle: Develop.

Development focuses on selecting and creating the materials that you’ll use in your training. You’ll write materials for the participants’ and the trainer’s use, create documentation, and evaluate materials. In this chapter, I divide the development of training into three segments: what you need to accomplish at the beginning of the training, in the middle, and at the end:

- Beginning: An opening that establishes a climate conducive to learning.

- Middle: A body that ensures that learning occurs.

- End: A conclusion that provides a sense of closure to the training and the anticipation of applying what was learned after the training experience.

Dive in when you’re ready to begin the development process, and remember to have some fun along the way.

Deciding Where to Begin

Your training design starts with the end first: the improved change or performance that you expect of each participant. The learning objectives that you write in Chapter 4 act as your guide to the design. List the objectives in the order in which you will teach them. You want to break down some of the objectives to the more specific skills and knowledge that each person will acquire to improve their performance. Can you see an outline taking shape? That’s exactly what you need to begin the design process! Consider the following abbreviated outline of the topics used for a train-the-trainer session:

- Opening and Introduction

- Overview of the Training Cycle

- Define training and trainer’s role

- Training cycle five stages

- Stage I: Needs assessment and analysis

- Conducting needs assessments

- Data-collection methods

- Analyzing the data

- Stage II: Learning objectives

- Types of objectives

- Writing effective objectives

- Stage III: Design and Development

- Adult learning theory

- Sequence and structure

- Learning methods and activities

- Stage IV: Facilitate the Design

- Trainer preparation

- Difference between presenting and facilitating

- Group dynamics

- Technology delivery skills

- Conducting activities

- Stage V: Evaluation

- Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluation

- Ensuring transfer of learning

- Designing evaluation instruments

- Using the data

- Training session follow-up

- Closing and wrap-up activities

How do you turn an outline into a training session? Entire books are written on the subject of designing and developing a training program. Some designers want you to use a specific model, identify confirming and corrective feedback, identify the rationale, create task listings, list the resources (a.k.a. markers), determine a task criticality rating, develop a process map, identify evaluation criteria, identify units, create an information map, and on and on. I don’t know about you, but I can’t keep that many concepts in my head all at one time.

What I can do (and you can do, too) is organize the content in a logical flow and figure out the best way to assist the participants to acquire the skill or knowledge required to achieve the desired performance. That’s what you need to focus on for now. If you want to go into more depth, I suggest that you contact your local ATD chapter to recommend a design course.

Choosing virtual, classroom, or hybrid

Before you continue too far with the design process, you need to determine how the training will be delivered. Someone else will most likely make that decision. The choices include instructor-led training (you will see this referred to as ILT) in a virtual or traditional classroom; on-the-job training (OJT); self-paced, asynchronous online training; or a hybrid model. Because of the pandemic, classroom training was down during 2020 and 2021. ATD’s 2021 State of the Industry Report noted that the use of classroom delivery was about half of what it was in 2019, and all forms of online, remote, self-paced, and other delivery types had increased. In fact, when all training was combined, the total number of available training hours had increased by more than 60 percent. This statistic tells me that employees had time to learn and they took advantage of it.

If you examine the outline on the previous page, you can see how you could keep the entire learning event together as a day or two in a classroom, or you could chunk it into eight or nine 90-minute chunks of content. These choices are why you need to determine the plan for delivery next.

ATD’s research report Virtual Classrooms: Leveraging Technology for Impact (2021) suggests that the heightened levels of virtual classroom use will continue. Most organizations expected virtual classroom use to increase or stay the same as they recovered from the pandemic. Likewise, organizations reported that they expected their e-learning use to continue to grow over the next five years. The advantages of online learning are that it

- Reduces travel time and costs

- Enables training to occur at any time and any place

- Asynchronous e-learning enhances the ability to offer just-in-time training

- Enables organizations to develop a global workforce

- May be more time responsive

The disadvantages of online learning are that it

- Requires learners to adapt to new technology and learning methods

- Requires more time and resources to develop

- May not be suitable for all content

- Is difficult to build relationships online

Blended learning

Blended learning is particularly effective when the best of both worlds is used — that is, the best features of online and the best of a face-to-face session. It is a “blend” of many activities to achieve a learning outcome. For example, it could begin with a traditional classroom, followed by asynchronous online work and self-study, and a 90-minute virtual classroom and self-assessment to wrap up. Mentoring or peer support could provide additional support.

Both participants and the organization benefit. Less time may be spent attending classes when content can be learned by reading or self-study, which learners can complete at their own pace and at a convenient time. Time in the face-to-face classroom is spent in building relationships that enhance peer feedback and also provides an opportunity for skill practice.

Flipped classroom

Flipped classrooms were first popularized by Khan Academy. Participants study and explore concepts, data, and information through reading, watching videos, or viewing a lesson online before attending the face-to-face classroom. Time in the classroom is spent on role plays, practice activities, case studies, and exercises related to using the skills in the real world. The facilitator does less presenting of new concepts and spends more time coaching the participants.

Using hybrid models

The hybrid model has been around for a while, but it intensified during the pandemic. You use it when a portion of your participants are in a room with you and the rest are on a screen remotely. Hybrid is not blended learning, but it may use some of the same techniques. The most critical part is to remember that you have members in two very different audiences. When you have smiling, excited people in front of you, you can easily forget about those online. It’s important to do what you can to build the community between the two groups. You may want to open the online group 15–20 minutes before the official start so that you get a chance to welcome them. Be sure to communicate your intentions in advance. You can also encourage the in-person participants to bring their computers so that they can interact with those online. When you wrap up, be sure to ask the online group for their greatest ah-ha or takeaway and then ask the in-person participants, “How many of you shared that experience?” Here are a few additional ways to make your next hybrid session sizzle:

- Ask an in-person participant to join the live stream to watch the chat, make sure you don’t miss any questions, and flag any issues.

- Consider emailing a survey, an agenda, an article, or other pertinent material ahead of time to build a sense of cohesion among all participants.

- I love to send a welcome kit to remote participants so that they have the same things the in-person group has. In addition to course materials, I include a snack, swag, and anything participants might need.

Starting to develop a program

The rest of this book flips back and forth between virtual, online, and other forms of training. Keep Jane Bozarth’s words of advice from the end of the previous section in mind and look for the advantages of each form of training.

You have been asked to develop a training program, but how do you get started? Following are the steps I use to design and develop a learning experience. I think you will find them easy to follow.

- List all the learning objectives for the session. These objectives form the basis for the content.

- If you need to break the objectives down to smaller, more manageable units, do so now.

Arrange the learning objectives into a logical learning sequence.

The sequences that are most often used include

- Chronological

- Procedural order

- Problem/solution

- Categories

- General to specific

- Simple to complex

- Less risky to more risky

- Known to unknown

Determine content to ensure that you have enough, but not too much.

What do your learners need to know? Need to do? What specific knowledge and skills will help them achieve the learning objectives?

- Identify the best methodology — for example, role play, discussion, practice — to use to transmit the content to the learner.

- Develop or purchase the support material you need to go along with what will happen during the learning experience, which includes some or all of these categories, with examples:

- Participant materials: Manual, handouts, job aids, texts

- Visual and media support: PowerPoint slides, videos, software

- Activity support: Role-play cards, scripts, exercises, props, case studies

- Trainer materials: Trainers’ guide, markers

- Administrative support: Agenda, roster, supply checklist, evaluations

- Conduct a pilot to determine what needs to be changed or improved to achieve success.

I devoted the rest of this chapter to how you fill in the gaps of the design outline you have created. It’s divided into the three different parts of the session: the beginning, middle, and the end. (How’s that for a logical sequence?) This chapter also discusses some of the methodologies you may use: lecturettes and more than 50 types of activities.

Developing a Dynamic Opening

Whether you’re in a classroom or on a monitor, the first five to ten minutes of your training design may be the most important of the entire session. A successful opening should accomplish several things:

- Establish a participative climate

- Introduce participants and foster relationships

- Introduce the agenda

- Clarify the participants’ expectations

- List objectives of the training

- Build interest, curiosity, and excitement

- Enable you to learn something about the participants

- Determine some minimum rules of engagement and ground rules

- Establish your credibility

Warming things up with icebreakers

Have you ever attended a training session when someone droned on for the first 20 minutes about the procedure for completing the sign-in sheet, where the bathrooms are located, how to get to the cafeteria, how to get your parking pass stamped, and on and on? Really got you excited about the training session, I’ll bet!

I like to start my sessions with something that surprises or shocks the participants. For example, after being introduced, I have started by walking in with a large shopping bag full of T-shirts and saying, “They say you can’t tell a book by its cover, but I believe you can tell people by their T-shirt!” I proceed to pull T-shirts out of the bag and read the funny sayings to the group. I hand them a bright sheet of paper (several different colors are used) with the outline of a T-shirt and ask them to use the crayons on the table to draw a picture or write a slogan on the T-shirt that represents their motto or what they stand for.

When participants have all finished designing their T-shirts — and it may take some prodding — I ask them to get up and find all the other participants whose paper is the same color as theirs, to introduce themselves to each other, and to explain their T-shirts (giving them about 5 minutes). Next, I have individuals introduce themselves and their T-shirts to the rest of the group. At the end, I have them all hang their T-shirts on the wall.

You discover in the “Selecting activities” section, later in this chapter, how I use the T-shirt theme throughout the session. But for now, what have I done?

- Grabbed their attention

- Established a participative climate and instant involvement

- Set the pace — fast

- Put people at ease (including the trainer)

- Initiated personal interaction and individual introductions

- Heard everyone’s names

- Had everyone speak once in the large group

- Started to define the group’s personality (trainer observation)

- Started to identify the individual personalities

- Created the opportunity for everyone to have learned something about each other

- Established a transition to the content

What? The content? Yes. I use this icebreaker for the train-the-trainer course that I teach, and after the final introduction, the class begins to process the icebreaker itself. This is where I slip in a reference about my credibility: “As a trainer for the last 40 years, I…” or “As the training director for…” or “As I discuss in my last book… .”

By the way, your opening in a virtual classroom should accomplish every one of the tasks in the preceding list, too. If your virtual group will meet multiple times — as is often the case — the time you invest up front during your icebreaker will pay dividends over and over. I used the T-shirt activity in a virtual teambuilding. Participants received a box of crayons and the same T-shirt in the mail about a week before the teambuilding.

As I write this, I’m staring at a quote written by someone who published an article in a training journal: “Icebreakers have nothing to do with course content, but they’re essential if you want people to work together.” Right on the last part, but absolutely wrong, wrong, wrong on the first part. With a little planning, you should be able to design an icebreaker that introduces the content. See the “Design content-related icebreakers” sidebar for further information.

If a group is composed of people who know each other well, an icebreaker may not be necessary for getting acquainted; there are other opening activities you may need to conduct. The first five to ten minutes is a very important time for your session. A well-designed opening and icebreaker establish a climate that is conducive to learning.

Considering other elements your participants expect

Your participants will expect you to design several orientation tasks to get the session started. If I am facilitating a session that lasts at least one full day, I generally allow about 50 minutes for the opening activities. I find that investing time up front to introduce the topic gains participants’ trust and equips me to be more helpful. Okay, so how do I plan for that time?

- Do the icebreaker activity: 15 minutes

- Have introductions: 20 minutes (1 minute per person)

- Review agenda: 2 minutes

- Conduct a mini needs assessment: 3 minutes

- Introduce learning objectives: 3 minutes

- Clarify participants’ expectations: 5 minutes

- Establish ground rules: 5 minutes

- Provide housekeeping information: 1 minute

Remember, these time allotments are estimates. Sometimes the icebreaker takes longer or participants get wordy with their introductions. Build some slippage into the rest of the morning. Believe me, this opening time is worth it. Of course, if this is a 90-minute virtual ILT, you need to adjust it and shave time off of each of these steps. Note that I said “shave time” off of each, not “eliminate.” For example, you can save time in your virtual classroom by sending the agenda, objectives, and ground rules prior to your session. At the same time, you could do a mini needs assessment. You could also use a quick poll to learn about your participants. You could ask participants to introduce themselves by posting their pictures or a video introduction to the group’s website discussion board or other location before the session.

Here’s what you need to develop in this list of opening activities:

- You need to design the icebreaker, and if you want a handout, you need to develop it.

- You want an agenda either printed on paper or accessible on participants’ tablets.

- Be aware of what information you need for the mini needs assessment. In the case of the train-the-trainer program, I wanted to know how long participants had been trainers, whether they had ever attended a train-the-trainer, whether they had designed training, and whether they thought that training was their destined profession.

- You may want to post the learning objectives and hang them on the wall after you discuss them, keeping them visible.

- You need a way to annotate participants’ expectations and the ground rules — perhaps compiled on a slide or flip chart pages. I don’t dictate ground rules; the groups establish their own. I find that they buy in and follow them better that way.

Finally, be creative. Think about ways that you could use Instagram, Twitter, or other social media tools for introductions.

Developing the Body to Ensure That Learning Occurs

After designing an opening for the training session that meets the requirements to establish a climate that is conducive to learning, you get started on the middle, or body, which is the bulk of the training. This part of the program requires that you design factors into the session that ensure that learning occurs. The purpose of the body is to ensure that your participants

- Accomplish the stated objectives

- Master the concepts presented

- Practice the skills

- Acquire feedback

- Apply what they learned on the job or beyond the training experience

Knowing the value of lectures

You know how important it is for learners to be actively involved in the training. Yet you may sometimes need to deliver new information, and a lecture may be unavoidable. In that case, you need to present the information. Even so, I never use the word lecture. I use a made-up word, lecturette, for these special times. It gives the illusion of being less tedious and a bit more playful! And that’s exactly what I am recommending you do with your lecturettes: Make them playful and learner centered.

Problems with a lecture

“So what’s so bad about a lecture?” you may ask. You’ve probably heard hundreds of lectures in school, and you survived them. It’s not that a lecture is bad, but there are better ways. First, consider some of the problems with a lecture:

- It doesn’t involve the participants.

- It ignores participants’ experience.

- It rarely stimulates excitement and involvement.

- Because of minimal feedback, the trainer has no way of knowing whether participants understand the concepts.

- It’s one-way communication, often resulting in passive learners who don’t have an opportunity to clarify material.

- People may leave with incorrect information.

- It can be dull and boring.

- Holding individuals’ attention for long periods of time is impossible.

- Success depends on a lecturer’s speaking ability.

- It creates a poor transfer of learning.

You may be able to think of other problems with lecturing as well.

Some appropriate times for a lecture

Despite the numerous problems with a lecture, as discussed in the previous section, there may be times when delivering a short lecture — or, as I like to call it, a lecturette — is best. Here are some of those times (and perhaps you’ve been in situations like these):

- A short presentation of less than ten minutes followed by another activity can be appropriate for introducing key conceptual ideas.

- When used in conjunction with a variety of activities, a lecture can be a refreshing way for participants to just listen while they learn.

- If you need to disseminate a large amount of information in a short period of time, a lecture may be appropriate. However, it should be accompanied by a job aid or some other materials for future reference.

- A lecture may be appropriate if you need to maintain control of the group and reduce verbal resistance.

- A lecture is appropriate when specific information must be disseminated that affects ethics, legal aspects, safety, and so on.

- A well-prepared, humorous lecture may stimulate a group.

- Guest speakers, who are known for their expertise in a given content area, may be admired for their lecture. This format can backfire, however, if the speaker loses the group.

- You may use a lecture when a group is so large that participative methods would be chaotic. (But sometimes chaos is fun in a large group!)

You may be able to think of other times when a lecture may be appropriate as well.

If you must use a lecturette, make it participative

If you must use a lecturette, have your learners participate in it. Try any of these suggestions for designing a participative lecturette. Most are practical and easy to design for any presentation, and most can be used online:

- Design pop quizzes in the middle.

- Plan to ask questions regarding predictions or recall of information.

- Create a conversation between trainer and participants.

- Intersperse tasks or demonstrations.

- Develop handouts with a keyword outline of the presentation, with room to write.

- Design visuals to go with the presentation so that participants can follow your words visually.

- Stop midstream at various points to ask whether everyone is with you.

- Design a partial story at the beginning and complete the story after the end of the lecturette.

- Find ways to interject humor, such as by creating a cartoon to match the content you present.

Contemplating countless alternatives to a lecture

There are hundreds of alternative methods you can use to replace a presentation. Recognize that many of these methods usually take longer than a lecturette, but a well-constructed activity enhances learning because the participant experiences the learning by being personally involved. For example, in the classic NASA “Lost on the Moon” exercise, participants experience the power and value of group decision-making.

Why would you use an activity, anyway?

- Activities are energizing. Use games in your design to give people a break, time to stretch (their brains as well as their bodies), to relieve stress, and just to get energized.

- Activities promote learning by doing. Your participants retain the knowledge better if you can engage as many of their senses as possible.

- Activities provide you with a way to reinforce information. It would be pretty boring if you stated the same things over and over in the same way, even though you know that repetition is good. Activities allow participants to experience the same information in another way.

- Activities are motivational. Learners respond because they are actively involved. It’s a pleasant way to learn.

Presentation variations

I use the term presentation to refer to any method that gives information to the participants with less interaction than many of the other methods. Here are some examples:

- Panel: Participants, managers, customers, or top executives provide a unique opportunity for an intimate discussion or a Q&A session.

- Tour: Visit someplace in the organization where a host guides you through the information you need to know, for example, the corporate library, to demonstrate how to retrieve information. You can take an online tour, too, which is especially effective for onboarding remote workers who wonder about things at headquarters.

- Guided note-taking: Create handouts that have spaces available to add information during a lecturette, watching a role play, or viewing a video.

- Storytelling: Telling an event (true or fictitious) that has a moral or lesson or demonstrates consequences. The punch line leaves the listener inspired, influenced, or improved, without explaining the learning point.

- Debate: Two teams address two different sides of an issue to explore perspectives from both sides.

Experiential learning activities

Experiential Learning Activities (ELAs), sometimes called structured experiences, are in a category of their own. ELAs are activities that are specifically designed for inductive learning through the five-stage cycle associated with them: experiencing, publishing, processing, generalizing, and applying. (You can find details for ELAs in Chapter 10.) ELAs are especially useful in a change-management situation, or when attitudes are an issue.

Demonstrations

Demonstrations typically involve someone showing the participants a process or modeling a procedure, for example:

- Instructor role play: Role play by two instructors to demonstrate a technique or make a point, followed by discussion.

- Field trips: Visit the location where the action takes place. If you’re teaching customer service, visit your call center and listen in on a few live calls to discuss technique.

- Video, DVD: Use clips from training, commercial videos, or sites such as YouTube as a basis to identify issues, solve problems, or consider examples to use as application options. Be sure to follow copyright laws or create your own recordings.

- Magic tricks: Use magic tricks to help you make an analogous point within the training session.

- Coaching: Sometimes conducted outside a training event, coaching can be used as participants practice a particularly difficult skill. Participants coach each other in pairs during role plays or other skill practice. Online participants can coach each other in a paired breakout room.

- Interviews: Participants ask questions of a resource person who attends the training session at a specified time. The purpose of the interview is to obtain another perspective, hear from the expert, or add knowledge. Online participants love a guest; that person doesn’t need to travel.

- Props: Oh, my gosh! So many possibilities! Bring tools that participants can use for the “As a team player, I am most like a ______________” exercise. Bring chunks of two-by-fours for participants to write the skills they have acquired and “build” the final structure. Bring packets of seeds and use as a metaphor for the “seeds of communication.” Well, you get the idea.

Reading

Reading refers to any method pertaining to interacting with the printed word.

- Read ahead: Materials provided to participants to read prior to the session.

- Letters to each other: Participants write letters to each other to provide feedback or as a summary of what each has learned in the session, or as follow-up after the session.

- Story starters: Give participants a partial situation and complete it by having them practice the skills and knowledge they’re learning in the session.

Drama

Drama refers to methods that require the participants or the facilitator to act out a role, for example:

- Skits: A short presentation by small groups to demonstrate skill or knowledge learned.

- Survival problem solving: Usually used as a team-building activity in which a team is placed in a role that represents danger. The team works together to make decisions and uncover their strengths and weaknesses.

- Costumes: Can be used by the trainer to make a point or play a role. Partial costumes — hats, for example — could be analogies for the different roles (hats they wear) that people play on the job. Hats are great online, too, especially for a group that meets regularly.

- Writing a script: Participants can script a role play for other participants based on the content.

Discussions

Discussion methods are types of two-way discussions that occur between participants or the facilitator (or both):

- Buzz groups: Two people “buzz” for one to two minutes about a topic before sharing their ideas with the larger group.

- Round robin: The trainer gets opinions from everyone in the session. Discussion or rebuttal is held until everyone’s ideas have been stated.

- Brainstorming: This is a process for generating a large number of ideas without judgment.

- Nominal group technique: Initially, you use this problem-solving tool to generate ideas in silence, and then weight and prioritize them.

- Online discussion: Use chat for group conversations, whiteboards for team collaboration, polls to start conversations, and breakouts for feedback and practice.

- Fishbowl: You divide the group in two, with half the participants sitting in a circle (the fishbowl) discussing a topic. The other half of the group sits around the perimeter and can coach during the discussion, silently motion to replace someone, or offer feedback at the end.

- Develop a theory: Participants make up a theory related to the knowledge or skills they are learning.

Cases

Cases generally refer to learning methods in which the participants are presented with scenarios requiring analysis and suggestions for improvement. You may want to try some of these methods:

- Case studies: A real or fictional situation is presented to the participants for them to analyze and recommend solutions. If an actual situation was presented, the facilitator usually shares the actual outcome.

- In-baskets: Items are given to participants that replicate problems, messages, and tasks that could actually show up in someone’s Inbox. Participants must make decisions, manage their time, and establish priorities as they address the items.

- Critical incidents: You present a short version of a case study, which focuses on the most vital aspects of a problem situation.

- Sequential case studies: You give participants a portion of a case study. Depending on the decision they make on the first portion, a second, third, and perhaps even a fourth set of data is distributed. All groups may end up in different places.

- Problem-solving clinic: Participants bring real-world problems for the rest of the group to solve.

Art

The art method entails using more creative methods involving drawing, design, sculpting, or other nonverbal events like these:

- Portraits: Participants create portraits of themselves being successful at learning the content of the session or as an opening activity to introduce themselves to the group.

- Cartoons: You use cartoons as energizers or to reinforce knowledge or skills that are being taught. Be sure to abide by copyright laws.

- Posters: Participants create posters to make a point, summarize information, and so on.

- Draw how you feel about _____: Have participants draw how they feel about whatever the topic is. You can reword this to have them draw a logo that represents teamwork, for example.

Playlikes

Playlikes are learning methods that are like dramatizations but less serious and more open ended:

- Role plays: Participants act out roles, attitudes, or behaviors that are not their own to practice skills or apply what they have learned. Frequently an observer provides feedback to those in character.

- Role reversals: Participants assume the role of the person with whom they interact daily, such as their bosses.

- Video feedback: Participants are recorded during a role play, skill demonstration, or presentation. They view their own recording and complete a self-critique. A bonus is to record it on their smartphone so that they can review it as often as they want.

- Outdoor adventure learning: Sometimes called ropes courses; used for problem solving and team building.

- Improv: Short for improvisation, actors create a skit without a script. They glean input and ideas from the audience.

- Simulations: A training environment that closely represents the real environment to allow participants to practice skills.

Games

Games refer to any board, card, television, computer, or physical event that leads to learning or review of material. A game requires a challenge, rules, and feedback resulting in a measurable outcome. Here are some examples:

- Crossword puzzles: Computer software can take a list of terms from the session and arrange clues and words into a crossword puzzle.

- Relays: Teams set up in a relay to compete to be the first to complete a set of instructions. Relays are good to use for a review of concepts to test knowledge acquisition.

- Card games: There are as many variations as there are cards! You can place various pieces of data on cards to solve a problem.

- Computer games: These are good for reinforcing skills back at the workplace after the session.

- Any board-game adaptation: You can adapt many board games such as Trivial Pursuit to the content of the training.

- Any game-show adaptation: You can adapt game shows such as Jeopardy! to the content of the training. Excellent online versions exist for you to use.

Participant directed

The method refers to situations in which participants take the leadership role in the delivery of training to others, or the analysis of their own learning. Here are some examples:

- Social learning: Though it’s usually considered informal and unconscious, social learning can be designed into a training event using social media tools such as wikis, blogs, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, TikTok, and others.

- Skill centers: You set up several areas around the training room to practice skills or test knowledge. Participants move from one area to another, selecting the ones most appropriate for them to master. Online, you can assign breakout rooms, and each has its own whiteboard with information.

- Teaching teams: Participant pairs select a topic from the agenda and teach the rest of the group. For online groups that meet regularly, assign one or two each session.

- Digital storytelling: Participants create a 1–2-minute video to capture examples or viewpoints related to the topic. Digital storytelling is effective for virtual and traditional classrooms.

- Self-analysis: This type of learning usually consists of a series of questions with correct answers to review knowledge. It may also consist of a set of thought-provoking concepts or questions that allow participants to examine their personal attitudes.

- Teach-backs: Participants receive a small portion of content that they study and “teach back” to the rest of the participants. You can conduct teach-backs in small groups or the larger group.

- Journaling: Participants keep a written record of thoughts, feelings, reactions, successes, plans, and action items. Journaling is an excellent online activity between classes.

- Research: You give a challenge in the classroom for participants to track down the correct answer between sessions. You can also use research assignments to have them locate information on the Internet during the session.

Participant events

This type of learning event involves learning methods that have a specific placement in a training session, including:

- Icebreaker: A structured activity usually used at the beginning of a training session to initiate participation and introductions.

- Energizer: A brief activity, exercise, or brain teaser offered to “energize” the group.

- Closer: A group activity used at the end to bring closure to the session, make commitments, review key points, plan application actions, and celebrate success.

As you peruse this list, you can see that with some adaptation, you can also use most of these activities in your virtual ILT. Some, such as videos and reading, can serve as preliminary work. You can use journaling, in-baskets, coaching, and self-analysis as follow-up reinforcement. Most of the rest can, with slight adaptation, be used during the virtual classroom. Think Zoom or Skype for a tour, or consider prepping a couple of learners to complete a role play or a teach-back.

Hey! What about gamification? Gamification uses game-based elements to motivate or engage people or promote learning. Gamification utilizes gaming elements to ensure a change in behavior and the transfer of learning to the workplace.

Selecting activities

Okay, maybe you’re exhausted just from looking at a few of the activity possibilities described in the previous section. How do you know which activities to select? Use two criteria. First think about the learning objective. In which learning category does it fit? Is it knowledge, skill, or attitude? Match the learning category to the activity. The examples discussed in this section show what I mean. You can use some of the activities for more than one category of learning. Don’t try to perfect this step in selecting activities — it just gets you started.

Next, consider other aspects of the activity. But first, examine the learning category examples that follow Karl Kapp’s sidebar.

Strategies for different learning needs

To know which type of activity to select, use the three categories of learning (knowledge, skills, attitude) as a guide. There will still be some crossover, but it’s a place to start.

Different types of learning require different strategies. Match the strategy (type of activity) to the learning objective. Keep reading for some examples.

KNOWLEDGE

If you want people to gain knowledge about something, furnish them with information through these activities: articles, short presentations, diagrams, recordings, or buzz groups.

SKILLS

If you want people to be able to do something and acquire a new skill, help them experiment by using these activities: case studies, demonstrations, role playing, videos and practice, exercises, or worksheets.

ATTITUDE

If you want people to change their values or priorities, assist them to inquire into and observe the old versus the new by using these activities: instruments, role plays, debates, structured games, exercises, or self-analysis.

Considerations for selecting activities

Here are some other questions you should ask when selecting activities:

- What is the purpose? Be sure that the design actually accomplishes what the learners need. If they need practice, don’t provide a word-match game or a demonstration.

- How well does the activity assist with accomplishing the learning objective? Sometimes a learning objective is broken down into smaller segments. Be sure that the time you invest in activities represents the most critical of objectives as well as covers the most of each.

- How much time does the activity take? How much time to debrief? This one is especially critical for online groups. If you don’t know how much time, better try it out with a group prior to the session. Don’t skimp on time if the knowledge or skill is important. Also, don’t try to save time by skipping the debrief. Participants leave an activity without a debrief wondering, “What was that all about?” If you don’t have time for the debrief, don’t do the activity. Also consider how rigid the time restraints may be for the activity, and know what you can do if you run short of time.

- Is the time investment worth the amount of learning that will occur? Concepts can be taught in many ways. Activities provide a hands-on opportunity for participants to master knowledge or skills that may be harder to master through discussion. Because activities take more time, it’s important to be certain that the concepts are related to the most important learning objectives.

- Is it fun — or at least stimulating and interesting? All activities don’t need to be grins and giggles, but if they aren’t at least interesting, learners will find something else to do — or think about. You know it’s true with virtual ILT! Admit it: Your mind drifts during virtual events!

- Do all the participants have the minimum skills to contribute and learn from the experience? Or are skill levels uneven among participants? The question speaks for itself. You may not know about everyone in the session; that’s why you’re constantly observing and learning about your group. If you suspect that someone will have difficulty, determine how you can offer support without being obvious. It may come from whom you pair the person with, what you assign the individual, or how you offer nonchalant sideline coaching. Sometimes you can create activities in which those with the higher skill level deliver the content.

- How comfortable does the activity seem? Your needs assessment should provide information about what is culturally acceptable in general. In addition, build up to riskier activities as the group is together longer. For example, role plays tend to be more acceptable later in the training sequence.

- Is the activity appropriate for the size of the group? Some activities that focus on creativity or mental imagery may seem threatening in small groups. On the other hand, some groups may be too large for certain activities, or space may be too limited to allow small groups to spread out to complete the activity. In a virtual classroom, ensure that you leave sufficient time to hear from all groups.

- Does this activity maintain the tone and climate the participants need? If you’re trying to build teamwork, it may not be wise to interject an activity that tears apart what you’ve built. If you’re encouraging participation, you may think twice about an activity that the quieter people may deem threatening.

- Does the activity have enough real-world relevance for this group? If not, you may want to find another, or add the relevance that’s missing.

- How flexible is the activity? Mold the activity so that the participants can easily relate to the situation.

- Will you be able to easily provide clear, succinct directions? The easier, the better. Remember that you may have 20, 30, or more participants in your session. If the directions are complex and you still think the activity is worth it, plan for how you can ensure that people follow the directions. For example, you could have the directions printed so that groups can read them, or you could dispense the directions in small doses.

- Will the learning that occurs be straightforward? If participants end the activity still requiring a lot of explanation, you will frustrate the learners. Better skip it.

- What is the timing and sequencing of the activity? Avoid conducting two similar activities back to back. Think about the time of day, as well. Incorporate activity and movement immediately after lunch. Increase risk as you move through the day.

- How may logistics affect the design? If you need to travel, you may not want to lug lots of props. Conducting a relay may be difficult if the room isn’t large enough. If two trainers are available, you may be able to include demonstrations or role plays. Equipment availability also shapes the activities you select. If your participants haven’t experienced virtual classrooms, placing them in a chat may take more time.

- Will the experience and the debrief provide participants with the skill or knowledge they need to acquire from the activity? Will you be able to easily relate it to the previous as well as the next training module? Finally, how will you evaluate the effectiveness of the activity you chose or designed?

One last word — or a few — about activities

Activities can be fun to design and plan into your training. Remember that balance is the key. To be most successful with activities or games in your session, you must be sure to do the following:

- Have a purpose. Don’t plug a game into a training session just because you have a space. Make it part of the design by linking it to a learning objective. Ensure that you include plenty of practice opportunities.

- Know the activity. During the design stage, try out any activities on a small group to see whether they accomplish the purpose for which you have selected the activity.

- Think variety. As you design the training program, include different types of activities. You’re unlikely, for example, to use more than one case study in a day when you have so many different activities from which to choose and so many learners with different learning preferences. Satisfy visual preferences through color, charts, pictures, and video clips. Satisfy auditory preferences with debates, discussions, and stories. Satisfy kinesthetic preferences through role plays, games, and practice.

Create a consistent theme. As you design a training program, think of a theme that you could use throughout, or an early event that you could return to, to create consistency. In the “Warming things up with icebreakers” section, earlier in this chapter, I share my T-shirt icebreaker. I continue to use the T-shirts that participants created during the icebreaker throughout the training program. Read on to see how I do that.

The group is in the team-formation stage, so I use it as a team-building exercise. Throughout the three days, participants write on each other’s T-shirts, completing these statements:

- Something I learned about you today is… .

- One thing we could do together is… .

- Something I’d like to know about you is… .

Finally, I use the T-shirts to bring closure to the session by having participants write on at least two other participants’ shirts with a request to “stay in touch” and add their contact information.

Adding Zest with Visuals

I can’t imagine facilitating a training session without visuals. They are so useful! Here’s what’s available:

- PowerPoint, Prezi, or other slide types of visuals

- Whiteboards, SMART boards, magnetic boards

- Flip charts, posters, chat, or graphics

- Participants’ own devices and laptops

- Props

Knowing why you need visuals

Why use visuals? The benefits far outweigh the problems they cause and the time it takes to create them. The first bullet is the most important one in this list of reasons to use visuals:

- Help participants grasp the information faster, understand it better, and retain it longer

- Clarify a point (a picture is worth a thousand words)

- Add variety

- Communicate the message both visually and aurally (through your presentation)

- Emphasize a point

- Make you more persuasive

- Help you be more concise

- Enhance a transition to change the focus

- Add color

- Keep you organized and on track (visuals cue you about content and what’s next)

- Help the brain transfer from short-term to long-term memory

Creating effective visuals

As you develop the visuals that will support your training, remember what makes them effective. Visuals are most effective when

- They are relevant to the subject (obvious, but I had to say it!).

- They are visible and understandable.

- Words are large enough to read.

- They are oriented to the listener: “Here are four ideas you will… .”

- Color is used appropriately.

- The typeface varies in boldness and size.

- The print is in both upper and lower typeface.

- The typeface enhances the readability (usually a san serif font).

- Bullets set off each point.

- The visual enhances your performance rather than replaces it.

- Visuals are tied together with a common theme — for example, a sketch, graphic, or background color.

- They are customized for the group.

If you’re sold on using visuals, review Chapter 11 to learn what you need to know during this design stage. The chapter is filled with tips to make you a savvy visual producer.

Designing handouts or participant books

Participant handouts should not be just a page full of words. You can ensure that handouts and other printed participant materials are effective if you consider these ideas:

- Know how the handout will function in terms of note- taking, exercise, and as a future resource. Match the text to the visuals you use.

- Use heads and subheads in a variety of type sizes and degrees of boldness.

- Don’t mix too many typefaces.

- Unlike with visuals, experts recommend that you use a serif typeface, to make the letters appear to flow from one to the next.

- Use graphics and sketches.

- Use bullets, dashes, borders, indentations, and margins for ease of reading.

- Number the pages.

Planning for Inclusivity

Trainers must be accountable for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). As my friend and inclusivity expert Maureen Orey shared, “You need to plan for inclusivity. Once you’ve finished designing the training, it’s too late.” Trainers talk about creating an environment in which learners feel safe and respected; they know they should arrive early to greet learners whether online or in a classroom; and they plan activities so that participants can get involved. All these are important; however, you need to take other steps to create a learning environment that is truly safe and respectful for all learners, including those with disabilities, who identify as LGBTQ+, or who come from diverse cultural backgrounds. Use the guides in this section to help you remember to consider both the content and the environment.

Reflecting diversity in learning and development content

Start with these guidelines to ensure that your program content is inclusive and represents diversity:

- To represent diversity:

- Select images that illustrate diverse people in everyday settings engaging positively.

- Ensure that clothing and hairstyles are representative and culturally appropriate.

- Use names, pronouns, and personas that represent diversity.

- To use inclusive language:

- Make sure that the roles you assign are equitable for all organizational roles: CEO; executive assistant; engineer; accountant; general counsel.

- Check for phrases or words that may be perceived as exclusionary.

- For multimedia:

- Use video clips with diverse actors or speakers.

- Review scenes to ensure that they are culturally appropriate and free of biases and stereotypes.

- When using sources/expertise:

- Cite diverse authors and thought leaders.

- Use quotes from diverse individuals.

- Use organizations and leaders who have a positive reputation for DEI when selecting examples or models of best practices.

Planning for inclusive learning environments

Equally important to the content is to consider how your training will be delivered. The methodology you choose will dictate how you will plan the delivery. Will it be online, in person, or a mix of both? Consider these guidelines as you develop your learning event:

- Instructors and speakers:

- Select trainers or training teams that reflect diversity.

- Ensure that panels represent diversity.

- When moderating a panel, make sure everyone has ample opportunities to speak.

- Invite guest speakers who are diverse or have a positive reputation related to DEI.

- Training location:

- Provide substantial classroom space for people with mobility issues to maneuver easily.

- Ensure visibility for all participants to see.

- Ensure that the facility is accessible for all needs (for example, is close to public transportation, offers accessible restrooms, and provides easy storage for food items for people with dietary restrictions).

- Activities:

- Modify activities that require moving around for people with physical mobility challenges.

- If online, ensure that appropriate equipment is available.

- Provide adequate breaks for people to take care of their physical needs.

- Provide a mix of activities to create learning experiences without exhausting participants.

- Instructor interactions:

- Use consistent greetings with participants to create an inclusive learning space.

- Give equitable attention to participants.

- Ensure that your micro-messages (eye contact, physical proximity, nonverbal gestures, facial expressions) indicate respect and inclusion to all.

- Learner participation:

- Communicate norms up front to ensure commitment to a respectful learning environment.

- Balance your requests for input from all.

- Mix up participants during activities to diversify groups.

- Consider assigned seating or breakout groups to maximize diversity in interactions.

Designing a Finale That Brings Closure

It’s 4:25 and your session is scheduled to end. Do you just say, “That’s all folks. Goodbye!”?

Well, of course not. Although the finale forms a small portion of the training session, it’s an important one to ensure transfer of learning beyond the classroom. How long to leave for this part of the training depends on the length of the session. If you’re giving a half-day session, you need at least 15 minutes. If it’s a two-or-more-day session, plan on at least 30 minutes. If it’s a 90-minute virtual session, allow 5 to 10 minutes. If you test participants before they leave, add time to complete the test. Remember that these are just guidelines from my experience. You may have a unique situation.

The conclusion should provide a sense of closure for the learners. It should also create anticipation for applying what was learned. Here are some elements to include in the design to bring about closure:

- Ensure that expectations were met.

- Provide a shared group experience.

- Evaluate the learning experience.

- Request feedback and improvement suggestions.

- Summarize the course accomplishments and gain commitment to action.

- End on time and send participants off with a final encouraging word — or two.

Ensuring that you’ve met expectations

One of the easiest ways to verify that you’ve met your participants’ expectations is to design time into the agenda to go back to the expectations they shared at the beginning of the session and ask whether you accomplished all that was expected.

Providing a shared group experience

You may want to design a closer for your session. You may use it to state a commitment about next steps, review key points of the training, plan for the next actions, or identify how to apply what was learned. You may also use the closer to celebrate success.

If the group has bonded, you may also want to do something that helps keep people in touch with each other if they work in different departments, at different locations, or even at different companies. A list of names and emails is an easy perk to supply.

I usually design a large group send-off experience. An old favorite goes like this: Have all the participants stand in a circle and ask each of them to state what they intend to do as a result of the training within the next ten days. I like this for two reasons. First, each statement gives other participants ideas of what they could implement. Second, this call to action helps participants bridge the distance back into the real world. You may have the same effect in a virtual session by asking participants to post their action in the chat.

Evaluating the learning experience

You should develop an evaluation for the session. Remember that you may need to evaluate at a couple of different levels. Chances are that if you’re new to designing training, someone else will assist you with the evaluation for the session. You can find additional information about evaluation in Chapter 7.

Requesting feedback and suggestions

You may also want to design time into the agenda to obtain verbal feedback and suggestions from the participants about how to improve the session before you offer it again.

Yes, you may ask some of those questions on the paper evaluation that you design. On the other hand, the group discussion often provides more useful ideas because they can be clarified. This is an excellent discussion to end an online session with.

Summarizing accomplishments

I usually build this summary of accomplishments into the shared-group experience in some way to save time. You may want to use a game or, if time is critical, conduct a brief large-group discussion at the close of the session. Examine the expectations and learning objectives to verify that they were all accomplished. Then ask for volunteers who could talk about how they intend to implement what they learned back on the job.

In the case of the train-the-trainer session, presented throughout this chapter, participants wrote a memo to themselves regarding two performance improvements they intend to make. When most people were finished, I asked for volunteers to share one of their improvements with the rest of the group. They placed the memo inside an envelope and addressed it to themselves. I collected them, and one month later, mailed the memos to each trainer.

Ending on a high note

One last thing I like to do is to put up a cartoon, a quote, or some inspiring thought that is both rewarding to the learners and pertinent to the next action they must take. In the case of the train-the-trainer session, I did two things, the first of which was to use a mind-teaser.

The participants were concerned about how they would remember all that they had learned. I have a slide that I put up in cases like this. The slide can be interpreted in two ways — with exactly the opposite meanings. Therefore, I ask people to read it out loud as soon as they see it. The slide says “OPPORTUNITYISNOWHERE”:

- Some read this as “opportunity is nowhere.”

- Others read it as “opportunity is now here.”

I explain that just as the letters are the same and can be interpreted two different ways, the learners are leaving the session with an experience that they can interpret in two ways. They have an opportunity to believe they will be successful, or to believe they will not be successful. And no matter what they believe, they will be right. It is really about attitude. The right attitude goes a long way with skills that are maturing.

For the second send-off at the end of the session, I asked them to take their T-shirts with them and hang them on their refrigerators at home. This is a super activity, especially if they have children. Mommy and Daddy are bringing home their schoolwork! It opens discussions at home about what happened in the training. The T-shirt motto is an interesting discussion point, but the comments that colleagues wrote on the shirt are even more interesting to families.

Finally, stand at the door, shake participant’s hands, wish them luck, and say goodbye. When ending an online session, say farewell to as many participants as possible and be one of the last to turn off your connection.

The schedule for the last half hour of the train-the-trainer session looked like this:

- Reviewed expectations on wall chart: 5 minutes

- Self-memo (two performance improvements I will make): 10 minutes

- Volunteers shared with larger group: 5 minutes

- Evaluated the learning experience: 10 minutes

- OPPORTUNITYISNOWHERE: 2 minutes

- T-shirts and goodbye: 3 minutes

Selecting Off-the-Shelf Materials

You may decide to purchase off-the-shelf materials instead of designing them yourself. However, you most likely still want to customize them for your organization. In that case, ideas throughout this chapter can help you with that task.

Determining whether off-the-shelf materials meet your needs

At first glance, purchasing materials that have already been designed and are packaged, tested, and ready to implement may appear to be a perfect solution. Here are some possibilities for locating prepackaged training:

- Presenters and speakers from consulting firms, speakers’ bureaus, and universities

- Asynchronous content or videos on almost any training topic

- Ready resources from your company’s corporate Learning Management System (LMS) and its learning vendor

- Public seminars offered regularly by training and consulting firms; some are on a regular travel schedule presenting in most large cities

- Packaged training programs that include the participants’ materials, a trainer’s guide, media and visual support, computer support and programs, and even the job aids, the “cheat sheets” that participants take back to the workplace to remind them of what they learned

- Customized training packages designed by training and consulting firms but created to your specifications; most start with a needs assessment

Adapting the design of a prepackaged program

Buying a training program isn’t always as easy as it sounds. To ensure that the design achieves what it needs to, you will most likely need to adapt the design to your organization by using these guidelines:

- Circulate the off-the-shelf program to key managers and participants. Ask for their suggestions to make it a perfect match for your organization.

- Review the program well in advance of the training. Make notes in the margins using company examples, anecdotes, policies, and so on that bring the topic home.

- Weave your organization’s core themes and philosophies into every part of the program. The skills and behaviors taught may be generic, but the way your organization applies them is not.

- If you’re teaching a technical process or procedure, add or delete steps to be consistent with the way the process is performed in your organization.

- If you’re teaching a behavioral skill, add comments that reflect your organization’s values and philosophy regarding the behavior.

So, make or buy? That’s the question. If you’ve decided to buy an off-the-shelf program, find out as much as you can about the package and the company before you buy. What exactly are you buying? How is copyright handled? Can you customize it to meet your needs? What do others say about the product? What kind of support will you receive? How consistent is the content with your needs and your organization’s culture? How much will it cost?

Pulling It All Together

At some point, you need to capture your design on paper. Most designers use a simple matrix to organize their scheme. Later, you or someone may write a trainer’s manual with much more detail. But for now, something simple will serve you well. The design guide that I use has four columns like the one you see in Table 5-1. Think of the design guide as a blueprint like one used in building a house. Use it to capture your plans. You see that it has just enough information to capture the flow of content from a big-picture perspective. You identify the knowledge or skill and the activity or method you intend to use. List also the support materials (participant handout, media or visual, prop) required and how long it will take. If you’re like most trainers, you have too much in your initial design. You may have 7 hours of available face-to-face time with your learners, and your design is 12 hours long. Trust me, that’s normal.

TABLE 5-1 Design Guide

Module _______________________________________________ Time _______________________________________________ | |||

Objectives: | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

Time | Knowledge or Skill | Activity or Learning Method | Support Materials and Media |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before you begin filling in the blanks, think about the factors that affect your design and the strategies you may consider. The next two sections present you with these considerations.

Understanding factors that affect a design

Every training design you create will be different. That, of course doesn’t mean that you can’t use aspects of a design or modify a design for two different purposes. You can. If you design often, take care not to fall into a rut of doing the same things over and over. Try something new. It keeps your designs fresh and keeps you inspired and interested.

Think of the following factors as the big-picture items you should consider before putting design pen (or keystroke) to paper:

- Content: How do you determine content? Content should be a natural offshoot of the learning objectives. Include what the participants need to know — not what would be nice to know. If you’re a subject matter expert (SME, pronounced “smee” in trainer jargon), you may have most of the information you need. Be sure to ask potential participants what they need to learn.

- Research: Start with the Internet or your organization’s library.

- Brainstorm: Get a group of people from your department together to identify resources and materials that may already be available.

- SME: Identify the subject matter experts and ask what you need to include. Be sure that they understand who the target audience is and their skill and knowledge level. Find out the six secrets to working successfully with SMEs in Chapter 15.

- Time available: How much time will be allowed for the training? The amount of time available for training depends on many factors: how critical the content is; whether employees can be spared from their daily work; and the length of the training.

- Participants: If you didn’t gather this information during the needs assessment stage, find out now the number of participants, how familiar they will be with each other, their level in the organization, and their knowledge level concerning the content.

- Culture: Determine anything unique about the culture of the organization or department that may be a concern as you develop the course.

- Cost: Find out how much money has been budgeted for the design and development.

- Trainer’s experience and expertise: Assess your skills and knowledge to determine whether you have the ability to develop your own activities and participant handouts.

Applying strategies for a good design

Of course, you want to design the best darn training possible. The following guidelines help you determine how to do just that:

- Variation: Use as many different methods and types of activities as possible.

- Timing: Plan for a high level of activity after lunch, decide on the best time for breaks, increase risk slowly, and ensure a mix of high- and low-energy activities.

- Participation: Design activities to keep participants involved and engaged.

- Sequence: Content should build on itself.

- Application: Design activities that relate directly to the learner’s real-world needs, ensuring that they have ample practice opportunities.

- Lecturettes: As noted earlier, present when you must, but keep it short and involve the participants.

Table 5-2 is a sample of one module of the design guide I developed for the train-the-trainer session described throughout this chapter.

As you examine the sample guide, try discerning some of the strategies I planned into the design:

- Sequencing of topics to build on each other as well as difficulty within the role play

- Variation in types of methods

- Variation in pace from moving around to sitting alone for self-assessment

- Variation in grouping size: pairs, five, self, large group

- High level of participation

- Variety in whom participants are learning with

- More time allotted for critical skill

- Minimal amount of time spent “telling”

TABLE 5-2 Sample Completed Design Guide

Module Facilitation Skills _________________________________ Time 155 minutes _________________________________ | |||

Learning Objectives:

| |||

Time | Knowledge or Skill | Activity or Learning Method | Support Materials and Media |

30 min | Preparation for facilitation | Intro with ten-minute interactive discussion: “what ifs” Small group guided discussion (Find someone on the other side of the room with whom you haven’t worked with yet — groups of five.) | PowerPoint Worksheet |

45 min | Identify training style | Complete self-assessment. Share in pairs to identify personal strengths and weaknesses. | Training style instrument Assessment sheet |

60 min | Co-facilitating skills Note: Critical new skill | Role play with observers. Three rounds with different person as observer each time. Role plays get progressively more difficult. Summarize in large group: what worked, what didn’t? | Role play card Observation sheets Team trainer checklist |

20 min | Apply co-facilitating skills to personal situation | Write memo to co-facilitator: more of, less of, continue doing. | Handout: Memo |

Developing materials

Materials support the training you have designed. You either develop or purchase these materials, which supplement and support each learning experience. Materials may include some or all of these:

- Participant material that includes at least the handouts or manual with information and note-taking space.

- Media or visual support such as a PowerPoint presentation to guide a mini-lecturette.

- Activity support that the participants may need for the activities such as role-play cards, self-assessment instruments, or checklists.

- A trainer’s manual to guide the facilitation of the session.

- Administrative support for keeping yourself organized or completing the administrative requirements of the session. It may include an agenda, roster, supply checklist, certificates, and evaluations.

When developing the participant materials, don’t try to include everything on paper. The activities you design tap into the knowledge, experience, and expertise of the participants. Participants should have a place to capture ideas they may want to use after the session. Allow space for note-taking.

Do consider job aids, performance-support tools, checklists, reference cards, and other guides for people to use after completing the session. Investing time to develop these materials, especially for tasks participants do infrequently or for complicated tasks, is a good decision. You still include these tasks in the design, but you free up some classroom time instead of increasing the amount of practice time for tasks that may not be completed very often.

Essential components

As you design participant materials, begin by knowing what content you will include and how participants will use them, such as assigned reading prior to or during the session. You also want to consider materials that are the basis for an exercise, the backdrop for taking notes, or are to be used as a future resource. Here are some guidelines for participant materials:

- Make content easy to read and information quick to find by breaking up the text with heads and subheads in a variety of type sizes and degrees of boldness.

- Use short paragraphs and wide margins, leaving space for taking notes.

- Use bullets, dashes, borders, indentations, and margins to enhance each page.

- Write in a conversational tone.

- Use graphics and sketches, even just lines and boxes, to set off key concepts and to add interest.

- Number the pages.

How about a trainer’s manual?

Your trainer’s manual may consist of anything from your notes written on the participant handouts to a complete manual with references to the training plan, facilitation tips, time use, media and visual list, and masters for the participant materials. A well-designed trainer’s manual

- Uses icons

- Has plenty of room for adding notes

- Identifies everything you need to know at a glance (what visual you’re using, what page participants should be on, what materials you require, and so on)

- Provides you with either a lead-in statement, a transition statement, or both

For now, I suggest that you allow someone else to worry about writing a trainer’s manual. Chapter 9 provides a few ideas about personalizing your manual.

Whew! That’s all, folks! As you can see, the development stage of the Training Cycle requires a lot of work — whether the training takes place in a virtual or face-to-face classroom.

The development of training is a big job, but don’t forget to have fun and to build fun into your design. You can do it. I pass on Henry Ford’s advice: “Whether you believe you can or you can’t, you will prove yourself correct.”

ATD’s Capability Model is divided into three domains: personal, professional, and organizational. This book focuses almost exclusively on the Developing Professional Capabilities Domain, and this chapter covers one of the capabilities: Instructional Design. It addresses the creation of learning experiences and materials that result in the acquisition and application of knowledge and skills.

ATD’s Capability Model is divided into three domains: personal, professional, and organizational. This book focuses almost exclusively on the Developing Professional Capabilities Domain, and this chapter covers one of the capabilities: Instructional Design. It addresses the creation of learning experiences and materials that result in the acquisition and application of knowledge and skills. Jane Bozarth reminds us that when we separate “‘traditional’ and ‘virtual’ classrooms, we suggest that they are entirely different undertakings. We need to remember that many activities used in traditional face-to-face training translate very easily to other environments.” She suggests that if you are mostly engaged in live-classroom work, you start paying attention to the times you conduct activities that are social and collaborative. Consider which activities can easily be translated to a virtual classroom or social learning.

Jane Bozarth reminds us that when we separate “‘traditional’ and ‘virtual’ classrooms, we suggest that they are entirely different undertakings. We need to remember that many activities used in traditional face-to-face training translate very easily to other environments.” She suggests that if you are mostly engaged in live-classroom work, you start paying attention to the times you conduct activities that are social and collaborative. Consider which activities can easily be translated to a virtual classroom or social learning. If you need to play with the sequence of the learning objectives, you can do it on your laptop, of course. Another possibility is to write each objective on a separate index card. Lay the cards on a table and move them around until you achieve what you’re looking for.

If you need to play with the sequence of the learning objectives, you can do it on your laptop, of course. Another possibility is to write each objective on a separate index card. Lay the cards on a table and move them around until you achieve what you’re looking for. Present content if you must, but build in participation.

Present content if you must, but build in participation. Thousands of activities, games, and exercises exist. I’ve published several that feature many of your favorite training gurus. If you’re looking for activities for your virtual ILT, start with these authors: Jane Bozarth, Darlene Christopher, Cynthia Clay, Jennifer Hofmann, Cindy Huggett, Karl Kapp, Becky Pluth, Kella Price, Clark Quinn, and Patti Shank. There are others as well.

Thousands of activities, games, and exercises exist. I’ve published several that feature many of your favorite training gurus. If you’re looking for activities for your virtual ILT, start with these authors: Jane Bozarth, Darlene Christopher, Cynthia Clay, Jennifer Hofmann, Cindy Huggett, Karl Kapp, Becky Pluth, Kella Price, Clark Quinn, and Patti Shank. There are others as well.