CHAPTER FOUR

Trust of Capability

The Third of The Three Cs: Trust of Capability

“Why doesn’t she just let me do my job?” Joyce, an event coordinator, asked in utter frustration. “It seems like every day, the boss is looking over my shoulder, telling me how to do my work. Why did she hire me in the first place, if she isn’t going to use my expertise? Doesn’t she have anything better to do?”

Have you ever felt micromanaged or underutilized because you weren’t able to use your talents to do your job in the way you knew it needed to be done? Did you feel like your education and years of experience counted for nothing?

“I’m not very confident Sam can do this job.” Abby, a programmer, confided to her colleague. “I don’t think he has the knowledge or skills to pull his own weight in getting this project done on time and within budget. His lackluster performance since joining this company has me very concerned. We have a lot riding on this project’s success.”

Have you ever felt concerned about the capability of a co-worker? Do you trust the people who pass work to you or those who take on the next leg of your projects? Do you think they’ll build on your good effort or screw it up and make you look bad?

These concerns and frustrations happen every day on the job. They whittle away at your ability to trust your own and others’ skills and abilities and diminish performance across your organization. In this chapter, we’ll show you how to build and sustain Trust of Capability in your relationships, and regain the productivity and job satisfaction you desire.

What Is Trust of Capability?

When you think of competence in your workplace, you may think of the formal tools used to measure and improve job performance: personnel policies aimed at tracking how well people do their jobs and formal training programs designed to teach them what they need to know. But competence on the job is more than education and training programs; it’s more than hiring and promotion policies; and it’s more than information, tools, and technology.

People trust in your capability when they have confidence in your competence to manage the demands and expectations placed on you by others—by your bosses, colleagues, employees, and customers. It takes more than task-specific skill to meet these demands: you also need to have the attitude, interest, and confidence that will help you work well with others.

Those “others” are an increasingly dynamic population of people from all ranks, levels of responsibility, and types of affiliation in your team and organization. As you work across boundaries and draw upon others’ capabilities on a day-to-day basis, you need to be able to trust that these relationships will produce the results for which you are individually and collectively responsible. You need to trust in others’ capabilities, and you need them to trust in yours. Trust of Capability infuses confidence in your effort and the outcomes it produces.

You know Trust of Capability when you experience it. You can see it, feel it, and hear it. People jump in to both answer questions and ask them. They don’t micromanage or disappear when help is needed. They move with confidence in meeting their objectives because they know collectively they have what it takes to get the job done—today and tomorrow. They want to work to their potential and feel confident that others do, too.

We all want to know that we are contributing

to the success of our workplaces.

Trust of Capability goes beyond confidence in your own and others’ current capabilities, however: it extends to having faith in your future potential to grow, learn, and develop. Do others believe you can take your skills, knowledge, and talents to the next level? Have you seen promise in someone else before he or she saw it in themselves? Has someone trusted in your potential and helped you to blossom? These are the questions at the heart of Trust of Capability.

We all want to be “seen”—to be recognized for what we have to offer and the value we bring to relationships within the organization we serve. We all want to know we’re contributing to the success of our workplaces—that our abilities make a difference. In practicing the Trust of Capability behaviors, people are able to work together to harness and leverage that need and motivation, and create a place to show up and do their best work.

When Michelle graduated from college, she went to work for the Southland Corporation, the global chain of 7-Eleven food stores. She was hired into the company’s management development program, which was designed to get people ready to run store operations. Once she completed classroom training, she went to work as a store clerk to learn the basics of managing a store—everything from inventory tracking, managing money, merchandising, and running promotions, to mopping the floors, stocking shelves, and scheduling staff. After working as a store clerk for three months, she was given her own store to manage. It was a 24/7 operation.

Michelle managed that store for three months and then moved into the position of area supervisor, which held her responsible for eight stores. She was twenty-two years old at the time. She ran those eight stores for a year and a half, and then was given a new group of eight stores, which she ran for nine months. And then she was given another group of eight stores, which she ran for close to a year. After proving herself as a competent area manager, Michelle was promoted to sales manager, and then district manager—a position responsible for running thirty-six stores and implementing corporate sales, marketing, and merchandising programs at the local level.

Just as she was finding her way in that level of management, Michelle was asked to take over another district that was struggling. This district consisted of thirty-eight stores that also had gas stations. It was the third-largest revenue-producing district of stores in the eastern United States, but it was not making money. Michelle had been identified for her ability to turn around failing operations, and she stepped into the job with a $40M budget and 350 people working for her. She was only one of two women at that level of responsibility—and the youngest and least tenured. At twenty-seven, she was seen as a shining star.

Michelle’s rapid progression might give you the impression that she was a master operator. The truth is, she was not. In fact, in a couple of cases, she was promoted beyond her operational knowledge and, in some ways, beyond what she was really ready for. There were times when she was nervous, vulnerable, and worried about whether she could “pull it off.” The operations were complex. She was young and still rather inexperienced. Reflecting back, Michelle believes the reason she was able to handle this level of responsibility so quickly was that she learned how to connect and build trusting relationships with others, and, in turn, trust in their capabilities.

The operations Michelle ran were outside of Washington, D.C.—a cultural melting pot. People who worked in her stores were from all over the world. She took an interest in them. She learned about their lives, their families, their hopes and dreams. She learned about their knowledge of store operations. And she asked them to teach her what they knew.

The company taught Michelle procedures and standards. She knew about gross profit margin and what she needed to bring to the bottom line: profits. She tapped into the people who worked for her to learn how to make that goal a reality. When she left 7-Eleven, her group of thirty-eight stores was one of the strongest performing in the region. She was being groomed for the next level.

Michelle received the gift of Trust of Capability—in capabilities that she didn’t even know she had. This trust from others allowed her to develop a kernel of self-trust, which gave her the confidence to reach out and ask people for help when she needed it. She extended trust in others’ capabilities and allowed herself to be taught by them. As she reached out, she discovered additional capabilities that allowed her to be successful beyond the limits of her defined skills and responsibilities. By giving her the freedom and flexibility to do her work her way, Michelle’s bosses increased her motivation and ability to perform beyond expectations.

Trust of Capability is required to get any work done, whether that work is a specific task or a more complex combination of activities. People need confidence in one another’s skills, abilities, and judgment to collaborate and perform at their best. When this confidence is missing, then expectations are not met, communications break down, and performance declines. Results suffer, as does morale and motivation. What can you do to head off these breakdowns by building and maintaining Trust of Capability in your workplace?

Four behaviors build and maintain your own and others’ Trust of Capability: acknowledge people’s skills and abilities, allow people to make decisions, involve others and seek their input, and help people learn skills. When you practice these behaviors up, down, and across your reporting relationships, you notice that others respond to your confidence in them, and they reach out to you for your expertise and support.

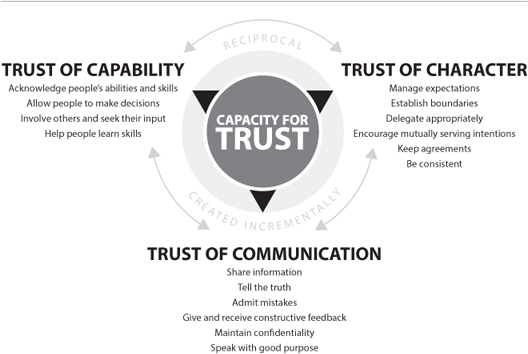

Three Dimensions of Trust

Behaviors that Contribute to Trust of Capability

You want others to trust that you know what you’re doing. And you want to be able to trust them in return. To earn this Trust of Capability, you need practice the four core behaviors that show others (and yourself) that you can be counted on to be trustworthy regarding your own and others’ abilities. Let’s look at each behavior in more detail.

Acknowledge People’s Skills and Abilities

“I have a lot of experience in this job, and one of the hardest things for me to do is to step back and let someone else do something,” said Joe, a pipe fitter. “It’s easier to just do the job myself than to guide someone through it correctly. Sometimes, I have to just step back and let other people struggle through as they learn to do the job their way.”

Do you acknowledge your colleagues’ abilities to do their jobs? Do you allow them the freedom and flexibility to learn and support them to discover their own approaches to doing good work?

When you acknowledge people’s skills and abilities, you’re letting them know you see what they have to offer and that you respect their abilities. You provide them with opportunities to use their talents and develop new ones. Most people want to engage with their workplaces in meaningful ways, to invest their time and energy toward measurable successes. You build Trust of Capability into your relationships when you support people to make a difference.

Extending gratitude to your co-workers for their contributions, giving one another the latitude to do the work they are delegated to do, and spotting opportunities for them to grow professionally are key ways to build Trust of Capability. Not only do you grow trust in your relationships through these actions, but you contribute to others’ capacities to trust in themselves. When people know they have your support, they’re empowered to learn new tasks, handle new situations, and view uncertainty through the lens of adventure rather than fear or doubt.

You build Trust of Capability when you extend

gratitude to your co-workers.

An added bonus to extending trust in your co-workers’ capabilities is that as they’re encouraged to grow and develop so are you. When your colleagues and employees assume additional responsibilities, you’re often freed up to take on new projects, initiatives, and roles that you wouldn’t have had the time or energy to tackle earlier. You also develop trust in yourself as a thoughtful, caring mentor—a level of self-trust that influences how confidently you engage in your own work and relate to others.

Anton, a developer, had an employee Margaret who was her own worst critic. She was so afraid of making mistakes that she couldn’t take risks—even smart, necessary ones. When she did take a step forward and happened to make a mistake, she would repeatedly beat up on herself. Margaret didn’t want to let the team down, yet her fear of letting the team down paralyzed her. She was so focused on her fear that she trusted the fear instead of trusting herself, and she continued to fail.

Anton took Margaret aside and asked if he could coach her. Margaret reluctantly accepted his offer. “I urged her to stay in the present,” Anton said, “and to focus on the objectives, not on the obstacles. I encouraged her to reach out and ask for the help of her teammates.” As Margaret began to focus on the task at hand and ask for the help she needed, she started to make some progress. Although she suffered a few setbacks, she started to trust herself and her teammates more.

Ultimately, Margaret was successful in accomplishing one major task, and then another and another. She started to gain a sense of success, and then pride in following through and accomplishing her goals. That was more than a year ago. Today, Margaret continues to grow, learning more about herself and developing deeper trust in her abilities as time goes on.

Anton often reflects on what he learned in coaching Margaret and how the experience allowed him to take the next step toward the position he wanted. Before Margaret, he wasn’t sure if he was ready for such a big promotion, but once he’d seen that he could be effective in helping others achieve their potential, he had the guts to apply for the position. Later, after he’d landed the job, Anton reflected on his experience with a colleague: “Sometimes,” Anton said, “another person’s trust in us gives us the courage we need to trust ourselves.”

We all have insecurities, doubts, and vulnerabilities as we stretch and grow. This is natural and healthy. It’s not a bad thing to question your own and others’ abilities to perform; there are times when you honestly don’t think you or they have what it takes to get the job done.

The key to moving forward when you have reservations is to reach out and ask for what you need, or find out more about what others need, to gain confidence. This act of reaching out will build Trust of Capability into your relationships. When others see you’re willing to ask questions rather than blindly make assumptions and risk deliverables, they’re more likely to trust you in the future. You gain their support and confidence. You become more confident in yourself to take risks and navigate challenging situations, and you become more likely to see the potential of others to overcome similar obstacles. Trust begets trust, and trust begins with you.

Allow People to Make Decisions

Organizational charts can’t be described in hierarchal terms anymore; the days of two-dimensional, top-down models for management are gone. In their place, people are benefiting from working relationships and teams that span rank, level of responsibility, and area of focus. Lines of accountability have been redrawn to accommodate these new environments, where people are encouraged to address issues, solve problems, generate new ideas, and ask for help when they need it. To be effective in such settings, people need to be able to trust one another to make good decisions to move their shared work forward.

Do you allow your co-workers the freedom and flexibility to make decisions? Do you give them latitude and discretion on matters that impact their work? Do you respect the experience, knowledge, and judgment that go into their decisions—particularly in their areas of expertise? Do you support them in the implementation of their ideas?

Or, do you second-guess, overanalyze, and thoroughly scrutinize others’ judgments? Do you fail to support the execution of their choices?

Sophia, an analyst, was given the sole responsibility to research the best options for launching a new line of business her company was planning. After nine months of extensive research, hard work, and due diligence, Sophia came up with three viable options. Her boss, Bill, took her work to the senior leadership team for review, excluding her from the meeting, and her ability to present her comprehensive findings. The senior leadership team took a mere five minutes to hear Bill’s review of Sophia’s findings, then quickly dismissed them. When Sophia heard the news, she was exasperated and deflated. “That’s the last time I am going to work that hard, for so long, and give my blood, sweat, and tears to this company. What was the point, just to be so promptly dismissed!”

When you aren’t allowed to contribute to final decisions that impact you and your work, or are contained within the scope of your assigned responsibilities, you feel devalued and disempowered. You may lose motivation to collaborate or contribute, and you might even begin to question your ongoing role in your team, department, or organization. You lose your sense of ownership and motivation for your work.

These same feelings are felt in others when you don’t allow them to make decisions related to their responsibilities. They feel devalued and begin to doubt themselves and their approach to their work. As a result, they question your intentions and will most likely take a defensive stance toward your future decisions. When you don’t extend trust and allow others to make decisions, you paint a big red target on your back for grievances about your choices.

When you aren’t allowed to contribute to decisions that impact

you and your work, you feel devalued and disempowered.

On the other hand, when you trust your co-workers’ abilities to make good decisions, you reinforce their trust in themselves, and you encourage them to trust your decisions as well. This exchange of Trust of Capability infuses your workplace with optimism, energy, and a collective sense that individual expertise is valued. You lift yourself and others out of the mindset of doubting, second-guessing, scrutinizing, and fear. You open up opportunities for breakthrough innovation, process improvements, and enhanced profitability. You discover you are capable of more than you imagined.

You may encounter situations where lack of experience—either your own or someone else’s—influences your willingness to support a colleague’s decision. This is often true in a new relationship, collaboration with new partners, or when you start a new project and the stakes are high. It’s important to understand the difference between appropriate trust and blind trust—and not fall victim to the latter. There are times when it is appropriate to involve others in a key decision.

“I allow people to make decisions when they demonstrate good judgment, aren’t uncomfortable asking for help when they need it, and are willing to give help as part of a team effort,” said Francois, a designer. “If I have doubts or concerns, I tend to be very watchful and offer assistance. I’m also proactive in being approachable, so they won’t feel uncomfortable to ask a question.”

When you extend trust and allow others to make decisions within the scope of their responsibilities—and don’t encumber them with micromanagement—you’re doing your part to create an empowered, productive, competitive workforce for your organization. The extension of this trust doesn’t mean you can’t ask questions, develop an opinion on core competency, and offer support or advice as a project moves forward. On the contrary, these actions form the basis of the Trust of Character behavior of delegating effectively. The idea isn’t to remove yourself from the decision-making process entirely, but to make sure the role you play in it generates trust in your working relationships.

Involve Others and Seek Their Input

Megan, an accomplished professional, was stepping into a new job. It was a big move up with lots of added responsibility. When asked about the first steps she planned on taking, Megan replied, “I’m going to spend a lot of time with my team and have them teach me what they know. I’m bringing myself in with humility and the understanding that I have a lot to learn. Yes, I’m there to lead, but I need to be open to hearing what others have to say if I’m going to be successful.”

Can you think of an occasion when someone asked for your advice or opinion? How did it feel? Pretty good? Now, think about how often you invite your co-workers to discuss options, give feedback, and help you solve problems. Considering how much you yourself like being consulted, are you surprised you don’t seek others’ input more often?

When you involve others and seek their advice in brainstorming, problem solving, or work project discussions, you demonstrate trust in their expertise. When people feel trusted, they are more likely to take ownership of—and feel pride in—a project’s outcomes. These feelings of pride inspire feelings of validation, which in turn cultivate your co-workers’ trusting approach to providing input the next time you ask for it. When you extend trust and ask others for their opinions, you not only gain perspective and knowledge about how to do your best work, you also gain their commitment to your project’s success. Ultimately, you do your part to create a more trusting workplace for both yourself and your colleagues.

A crucial warning: asking for input can’t just be “lip service.” The only thing worse than not being asked for your opinion is being asked, then having your thoughts, ideas, or concerns discounted or held against you in the future. These situations can lead to feelings of betrayal, as you or others suspect that your involvement was sought only to fulfill a line item on a checklist. The result may be that you don’t feel safe enough to participate in critical discussions of problems or confident enough to ask for others’ feedback when you really need it.

Trust of Capability is built on the confidence in your own and others’ individual contributions to the workplace. When that confidence is fed, so is trust. With trust, you and your co-workers are able to engage one another in meaningful, respectful dialogue and explore possible alternatives to shared challenges. You feel safe to question one another’s assumptions in appropriate ways; secure in the knowledge that one person’s new idea doesn’t have to mean loss of power or authority for anyone else. The end result is an environment rich in Trust of Capability—one that ensures the full contribution of each colleague according to his or her talents, experience, and creativity.

Help People Learn Skills

“I need to know where a person’s skills lie to make me feel confident in delegating a task,” said Erik, a project manager. “So I talk with people before I delegate to see if they have the experience needed or if the task will require them to develop new skills. This helps me to know the type of support they need. It’s extra work on my part, but the look on people’s faces when they’ve learned new skills is priceless.”

Do you take time to discover how you can help others do their best work? Do you take risks and tackle new ways of doing things, learn new skills—and encourage others to do so, too?

Investing in your co-workers’ development is a powerful way to build Trust of Capability into your relationships with them. When you help your colleagues learn new skills, you demonstrate your trust in their potential and their ability to become the best versions of themselves. You create the space where they can discover what they’re capable of achieving. And you build Trust of Capability across the organization as others see that you’re committed to your colleagues’ success.

When you help others learn new skills, you

demonstrate your trust in their potential.

The pace of today’s work can make it hard to find time to encourage others (and yourself) to learn new skills or develop existing talents. Staying “current” can take a lot of your time and energy, leaving little in reserve for “extra” work—even if that extra effort would pay off in the long run. Finding the time to encourage your co-workers to stretch and grow may be difficult, but it’s a habit that, when developed, pays off in performance and creative problem solving—possibly in your next big project. When you and your colleagues are better equipped to do your jobs well, your results, job satisfaction, and competitive edge more than compensate for the time you invested in professional development. You grow as individuals. You grow as a team.

You can’t afford not to make time for training that helps you develop. You have a responsibility to yourself to stay on top of your game.

You want to work in an organization that offers a wide array of training programs, workshops, conferences, and learning opportunities to observe others’ methods and practices. You’d like to encourage and enable others to continue their formal education, take on special projects, or step into promotions that would further develop their skills and experience. But these opportunities aren’t always immediately available—or available at all—due to funding, the size of your organization, or the sophistication of your co-workers’ current skill sets.

Even if these formal mechanisms for professional development aren’t available, don’t forget your strongest asset for deeper learning: those within your organization with long tenure, proven expertise, and invaluable perspective. When you recognize and tap into these rich sources of mentoring and coaching, you not only learn from their proficiency and longevity, you engage a group of people who may have been feeling discounted or irrelevant. Your colleagues at the top of their career ladders have a wealth of technical and organizational knowledge that can rival formal professional development tools. Forging bonds with them can help you cultivate your own and others’ capabilities—and build additional trust into your relationships as they respond to your respect for their lives’ work.

Developing your own and others’ competence can be thrilling and empowering. Through working together to highlight strengths and address weaknesses, you empower yourself and others to go beyond expectations in discovering your collective potential. Trust of Capability grows when your co-workers get better at what they do, take more joy in doing it, and encourage others to follow their lead toward a more effective, vibrant workplace.

Developing your own and others’ competence

can be thrilling and empowering.

Dealing with Disappointment

What about the times when your support of others’ competence doesn’t work out? When you trust your co-worker with a major project and he or she drops the ball?

Larry, a partner in an accounting firm, shared a hard lesson he learned: “Having Trust of Capability is not blind trust—you’ve got to follow your intuition. I allowed Susan, who was outwardly very confident, to ‘snow’ me. Susan’s confidence overshadowed a slipshod approach to her books. I trusted her, but I should have followed my instincts. She didn’t perform up to my expectations.” By the time Larry realized Susan wasn’t performing up to par, it was almost too late. The books were due, and Larry’s co-worker had failed to deliver. Larry reflects: “The lesson for me is ‘Do not be afraid to confront.’ A lot of external distractions clouded my intuition. Because of my trust in this person, I made an assumption that Susan should know how to do this closing. I mistook her assertiveness and confidence for competence. I needed to trust my intuition.”

This story illustrates the hard lesson that trusting in others doesn’t mean you should neglect your common sense. It’s important to review each situation carefully “with open eyes” to determine whom you can trust with what. You may trust in a person’s competence more than he or she does: this is a situation ripe for your coaching. Other times, you may feel like you should trust, but something is telling you otherwise: this is a situation that warrants more measured, controlled delegation of a major project. You need to listen to yourself and follow your intuition.

And there are times when, despite your co-worker’s very best efforts, you may still be disappointed in results: “I asked you to do X; you gave it your best effort but came up short. I am disappointed.” When a person has honestly tried to accomplish a task but failed due to lack of skill or aptitude, you may feel let down. It’s important, however, to realize your colleague’s behavior isn’t a betrayal per se—it may be an honest shortfall in meeting your expectations. He may have not have been aware of his own shortcomings.

In these situations, it’s vital that you take a close look at your role in the breakdown.

Did you provide him any support throughout the project? Did you hold back your trust, making it difficult for him to ask for help when he needed it? Did you not trust your intuition?

Contributing to the growth of others starts with raising your awareness of how you bring yourself to your relationships. Through reflecting on these questions, you may find you need to shift your perspective and be open to trusting yourself and others more fully. You may need to reframe habits, thoughts, and perceptions that have caused you to hold yourself and others back in the past. You can choose to behave differently in a way that better serves you and your relationships. Remember: trust begins with you.

Disappointments can be opportunities to reframe

your behaviors and improve your relationships.

There will be times when you’re disappointed, even frustrated, by a co-worker’s performance—or lack thereof—but you’ll benefit in the long run if you continue to provide support. You can help the person see how he or she can enter into similar situations differently in the future or illustrate how to tap into others and leverage their skills and support to be successful. An old Chinese proverb is as true today as ever: “If you want one year of prosperity, grow grain. If you want ten years of prosperity, grow trees. If you want one hundred years of prosperity, grow people.”

Trust Building in Action

Reflecting on Your Experience

1. Where in your personal and work life do you experience high levels of trust in your capability?

2. Of the four behaviors that contribute to Trust of Capability, choose one or two that you feel represent opportunities for you to build more trust in your relationships with others.

![]() Acknowledge people’s skills and abilities

Acknowledge people’s skills and abilities

![]() Allow people to make decisions

Allow people to make decisions

![]() Involve others and seek their input

Involve others and seek their input

![]() Help people learn skills

Help people learn skills

Trust Tip ![]() When you trust others’ capabilities, you demonstrate that you value their skills and abilities by giving them the latitude and flexibility to do their jobs, instead of micromanaging them. Doing so increases their commitment, motivation, and performance.

When you trust others’ capabilities, you demonstrate that you value their skills and abilities by giving them the latitude and flexibility to do their jobs, instead of micromanaging them. Doing so increases their commitment, motivation, and performance.

Summary of The Three Cs of Trust

This chapter concludes our exploration of the Three Dimensions of Trust: The Three Cs. Before moving on to the next chapter where you will explore your readiness and willingness to trust, pause and review The Three Cs and their related behaviors in concert with one another.

In our work with people around the world, we’re often asked if trustworthy relationships can thrive based on only one dimension of trust. The answer is: No, not for long. The Three Dimensions of Trust are interrelated. Although you may choose to focus on strengthening one dimension of trust within a specific relationship at a specific moment, your overall approach to building sustainably trustworthy connections must holistically incorporate all three dimensions and their respective behaviors.

To help clarify this truth, consider the last time you were hired for a position based on others’ trust in your capability. Although your subject matter skills and talents landed you the job, you needed more than technical prowess to be effective in your team. Your boss, colleagues, direct reports, clients, and other stakeholders needed to know they could trust your word and character as deeply as they could trust your ability to complete a series of tasks. The Three Cs of Trust work hand in hand in the creation of sustainably trustworthy relationships, teams, and organizations. You have the opportunity to contribute to this trust-based community by practicing the behaviors within each dimension of trust. Trust begins with you.