Family Business Decision Making

How Families in Business Make Decisions

Although it is of vital importance to a family firm, there is little information on the subject of family business decision making. The most useful information is contained in a single article from Aronoff and Astrachan,1 who found that 34% of founders made the decisions themselves, 48% of family businesses searched for a consensus, and 6% discussed the issue and took a vote. Fifty-three percent of the voting group is made up of the third generation of family leadership. This suggests a higher level of governance and professionalism among the later generations, accounting for better planning and organizational control.2 An increased use of succession planning among both the second and third generations also gives evidence of a higher degree of professionalism in later generation family firms.3

The research shows conflicting data in our existing knowledge of family business decision making. Feltham, Feltham, and Barnett4 discussed the situation of a single, dominant, key decision maker; Aronoff and Astrachan5 discussed a single decision maker in the majority of firms they studied but found a large number of firms searching for consensus and some firms using a democratic voting process. Family values, personality traits, and their fit within the firm were found to be more influential than strict professionalism in a study of human resources decision making.6

Ibrahim, Angelides, and Parsa7 discovered a nimbler and faster decision-making process compared with nonfamily firms. Conversely, Prince and File8 described a slower decision-making process, with more people involved, and Miller and Le Breton-Miller9 recorded decisions based on the beliefs and values of the family. Miller and Le Breton-Miller10 discussed how Francois Michelin, the former CEO of Michelin, made decisions. When faced with “tough decisions,” he did not make decisions by the financials or the investment community “but according to the enduring beliefs of the family.”11

Prince and File12 conducted several significant research studies on marketing to family businesses from the financial services perspective, including a 1995 study that presented the problems and issues associated with selling products to family businesses. These issues included

• multiple decision makers

• decision makers not actively involved in the business

• a significantly longer decision-making time requiring multiple calls and meetings

File13 surveyed the decisions of 396 family businesses involving both significant family involvement and a lack of family involvement. File divided the family business decisions into four groups:

• Category 1. The decisions had high importance to the business and evoked significant family involvement. These decisions included compensation, benefits, and financial allocation and capital equipment decisions. Included were consulting services decisions and marketing communication decisions.

• Category 2. The decisions had a high importance to the business but evoked little or no family involvement. These decisions included technically complex purchases such as accounting services, property insurance, legal services, software purchases, computer equipment, security services, and telephone leases and purchases.

• Category 3. The decisions had a low importance to the business but evoked significant family involvement. Decisions included employee insurance, buy-sell agreements, and highly visible corporate philanthropy efforts.

• Category 4. The decisions had low importance to the business and evoked little or no family involvement. Decisions included travel agency decisions, car leasing, office design, long-distance providers, and printing services.

An important finding in File’s14 work was the increased involvement of the family in issues that could include favorable exposure of the family and its business philosophy to the community, such as marketing communications and philanthropic efforts. Confirming File’s work on family involvement and delays in decision making, Sharma and Manikutty15 reported that increased family involvement, increased divestment decision making, and resource evaluation decision times.

Goffe and Scase16 highlighted controlling family members and a lack of delegation to nonfamily management employees on key decisions as important elements in family businesses. They studied delegated decision making in 12 family firms in the general building and personal services sectors in the United Kingdom. Four of the firms were operated by the first-generation founder, while the remaining eight were inherited. The firms ranged in size from 30 employees to 1,200 employees, with an average employee count of 300. They found a fluid type of decision making characterized by a lack of management formalization. Family member owners used a consultative approach with management, yet it was the owners who made the important decisions. When the authority was given to make decisions at a lower level, management was “allowed to make some of the decisions some of the time.”17 They showed that, even when delegating, ownership retained control of decision making through the use of “insidious controls, setting of agendas, strict regulation of the amount of information available, and communication channels.”18 Positions that required “overall control”19 were reserved for family members.

Carney found the attributes of family firms that result in their ability to outperform nonfamily firms are “embedded”20 in the firm’s system of corporate governance. Based on the nature of ownership and control “rights,”21 family firms exercised the rights in decision making on a level that is not available to those in nonfamily governance systems. According to Poza, “Family businesses may be able to make decisions more quickly and therefore take advantage of opportunities that others may miss. Quick decision making is critical in business, and tight-knit families in business move fast.”22

In a study of over 300 family executives, family firms had quicker and more effective decision making because they had less bureaucracy. The decision-making hierarchy “may be completely ignored, existing only to be bypassed,”23 which often frustrates outsiders. People who are accustomed to working in corporate environments consider so much overlap of job responsibilities and the lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities to be messy and confusing. This may help to explain the negative connotation of family firms being unprofessional mom & pops that lack management skills. Often, when a family business makes a personnel decision, they use the perspective of family values and personality fit issues, rather than basing decisions on strict performance criteria.24

A Model of Second-Generation Family Business Decision Making

To fully understand the nature of family business decision making, the differences between the generations should be explored. An entrepreneur is often a dominant personality who makes most of the decisions. This leaves succeeding generations ill prepared for decision making in the absence of the founder. Heavy dependence on a single entrepreneurial founder underscores the centralized decision-making process common in the vast majority of first-generation firms. In a study of 765 family firm executives, the organization was either dependent or very dependent on a single decision maker in 75% of the firms surveyed. Feltham et al. discovered founders exhibit such control over decision making that 31% made all the major decisions, including 87% of all finance decisions. Entrepreneurial founders also tended to utilize intuition and heuristics as a way to make decisions.25

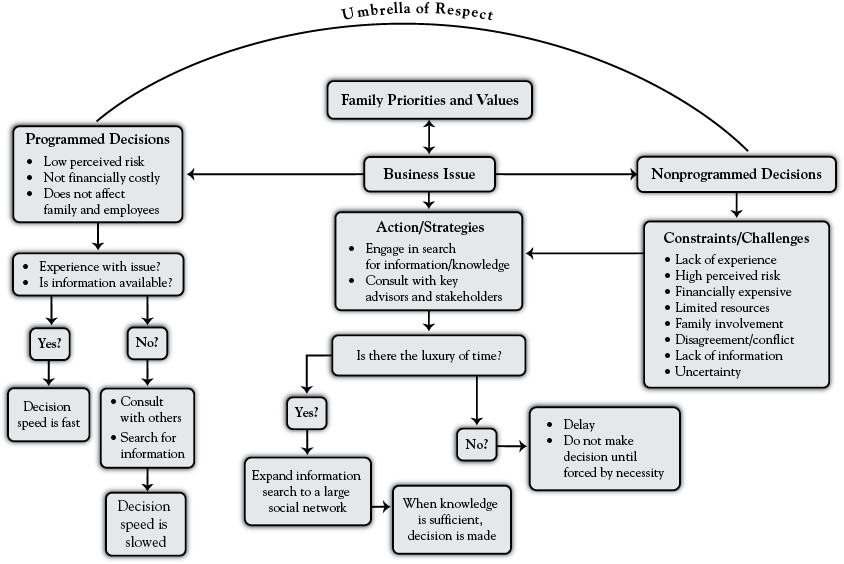

Research among 15 senior-level second-generation family business members (depicted in Figure 4.1) showed the second generation did not make decisions without complete information unless forced, did not feel comfortable utilizing intuition, engaged in a broad search for knowledge and more information, and had a larger social network they used to gather information and discuss business issues than their first-generation predecessors did. The second generation used a consultative decision-making style to obtain the needed information and arrive at a decision. These are major areas of difference, compared with the first generation. The second generation therefore seems more rational than the previous generation, yet not as rational as the third generation. The third generation is different from the second generation with a tendency toward the more professional consensus approach and majority voting.

Figure 4.1. A model of second-generation family business decision making.

Source: Alderson (2009).

The need and ability for family decision makers to obtain whatever information is required is exemplified as follows:

I make my decisions the reverse of my parents. When I make decisions that I have the authority to make, I’ll talk to one of the managers who it will affect. I’ll talk to my parents about it, talk to who it concerns, talk about the issues, and then I’ll make the decision.26

I mine for more information. Always, if I don’t feel I have enough information to make the decision, I’ll do whatever is necessary to make the decision. I’ll do whatever is necessary to get more information. One thing I want . . . you know . . . haste just causes more mistakes in the long run.27

Figure 4.1 shows the umbrella of respect at the top of the model, overseeing all the activities of the firm. This term describes the high level of respect and reverence for the accomplishments of the first generation. All decisions are immediately filtered through the founders’ stated priorities and values. The decision maker first makes sure the decision is not in conflict with the family’s mission. Then, the decision maker proceeds to make the decision.

All decisions are divided into two main types: programmed decisions (i.e., small decisions or those made numerous times before) and nonprogrammed decisions (i.e., larger decisions that are made infrequently). These decisions almost always lack adequate information to make a good decision. They are financially costly, perceived as risky, and often involve several other members of the family. The result is a slowed decision-making process.

A retail store owner discussed the respect he has for his father’s accomplishments:

Dad ran a very successful large corporation (Fortune 500). He retired and went out on top. He started this company in 1982. I learned all I know from him. I am not real bright; Dad is, though. I always yield to him. I have a lot of respect for Dad. I am lucky; he’s like a prop. I am not sure what I am going to do when he dies.28

A third-generation retail store owner described his father, only half jokingly:

Now that he’s gone, I look back and he was right. It’s like Samuel Clemmons said: When you’re 5 years of age, Dad is great; at 15, he’s a moron; and later in life, Dad was pretty smart! My dad was like God. No, he advised God! He was God’s advisor!29

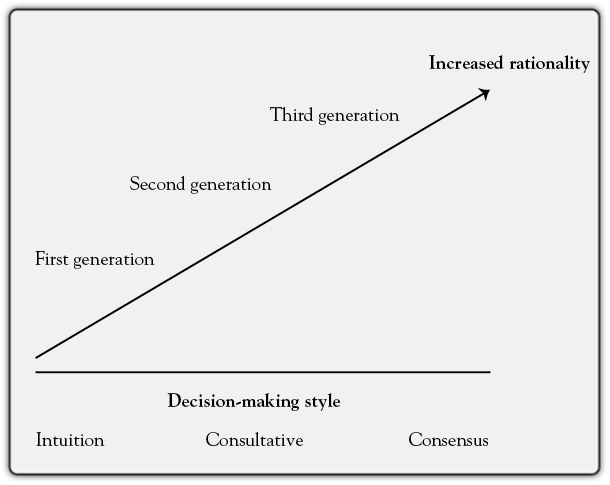

The Family Business Rationality Continuum seen in Figure 4.2 graphically depicts the increase in rationality from the first through the third generations. There is no data specifically focusing on the fourth generation and their decision-making processes. Based on the larger family size and business growth, it is likely that the fourth generation is increasingly rational as well, including embracing the addition of nonfamily professional management.

Figure 4.2. Family business rationality continuum.

Source: Alderson (2009).

The third generation is often larger than the second generation. It involves various family members, many of them equal partners, including some family members who may not be employed at the family business but who have an ownership stake. To maintain harmony, family members often use a consensus style of decision making and often a majority vote is taken. This increase in rationality was confirmed in the literature by Aronoff and Astrachan,30 who determined the third generation (the cousin consortium) used the more rational consensus or voting approach.

Research has shown the longer a family firm has been established, the more successful the firm is. Especially if a generational transfer has occurred, rationality and logical decision making increases. In other words, family members make decisions more carefully, with a variety of solicited inputs, in order to maximize the decision effectiveness.