Success Tips for Family Business Owners, Employers, and Professionals

Danny Miller and Isabelle Le Breton-Miller studied 46 successful family businesses, including Wal-Mart, Nordstrom’s, Bechtel, Coors, Corning, Fidelity Investments, Tyson, IKEA, and Cargill. The researchers’ purpose was to uncover what made these firms so successful and gave them the ability to thrive as family firms. They arrived at what they called the four Cs: continuity (a long-term focus), community (a strong cohesive team focused on values), connection (a deep relationship with key stakeholders such as the local community and suppliers), and command (an empowered top management team unfettered by bureaucratic rules, thus enabling them to move fast and seize opportunities).1

To survive for multiple generations, a family business needs enough flexibility to accept transition and the ability to recognize opportunity when the markets or business environment has changed.

Family Employment Policies

Although no hard research data exists yet, consultants who advise family-owned businesses increasingly suggest that the next generation of family leaders should not enter the family firm until first working outside the company. Many professionally managed family firms subscribe to this excellent practice. When the child wishes to enter the business, employees and parents alike will have an increased level of respect for him or her. Ideally, the sons or daughters should work in a business where they will develop new knowledge or skills or in a firm in a different market that can help them when they enter the family firm. For example, it would be beneficial for younger family members to have worked in a retail grocery chain before entering the family’s grocery distribution business. Many firms require the family member to receive at least one promotion at the firm in order to demonstrate the individual is qualified and will be able to make a valued contribution to the firm. Then the family member is seen as adding significant value and is accepted as a deserving member of the team.

Many family firms have instituted policies and procedures to govern the hiring of family members and to indicate what is required before family members enter the family business. Many businesses require children of business owners to obtain a university education and work outside the family firm for a period of 2–3 years before entering the family business. There are multiple reasons why consultants recommend the outside work experience, but most revolve around respect, competence, and confidence among the following three stakeholders:

• Employees. When the children of the owner first arrive at the company, the existing employees believe it is mainly due to their last name. If the job is not earned or deserved, the existing employees will not respect the family prodigy, and disruptive conflict can flare up. By arriving at the company fully qualified, employees will more readily accept the offspring rather than derail them or engage in nonproductive interpersonal conflict.

• Parents. Very often, parents have a difficult time accepting their son or daughter in the family business at anything other than employee status. This is due to the established family roles. (Let’s face it, they have changed their diapers.) It can be a difficult transition for the parents to see their children as valuable members of the business who can make a contribution, rather than as the dumb kid who threw a rock through the church window (like the author did). This transition can be significantly eased by the children finding success outside the family business and entering the business with increased knowledge, skills, and management techniques that can add value and help the business grow or become more efficient.

• Themselves. The young family business leader will have more confidence upon entering the family business if he or she has succeeded elsewhere. Such second-generation members will know it is due to themselves as individuals and not their name or family connections. Even if the next-generation member has outside business experience, some current stakeholders will still harbor suspicions or a bias that the job may not be deserved. The extra self-confidence gained by working outside the firm is priceless.

The family employment policies are documented in the family constitution, and this document should also spell out policies for family employee appraisals, feedback, mentoring, and procedures for developing career plans. Some firms have family members report to nonfamily managers to avoid possible conflict of interest or nepotism issues.

Start the Children Early in the Family Business

Many entrepreneurs got their start by working in the family business when they were young. Statistics show that some stay in the family business, some pursue their own career ambitions, and others move on to start their own entrepreneurial ventures. However, the child of a business owner is two to three times more likely to become self-employed than the child of a nonbusiness owner. In fact, those youths who were actively involved in the family business tend to do better. Business owners who had previously worked in the family business were associated with a lower probability of business closure, a 40% increase in sales, and a higher probability of profits.2

Several of today’s business moguls are good examples of entrepreneurs who learned the meaning of hard work early in life. Warren Buffett, one of the richest people in the United States, had a paper route at age 13; his father was a self-employed insurance and investment broker. Forbes 400 member Donald Trump learned the real estate business from his father; his children are now learning it from him. CNN founder Ted Turner learned the media business working in his dad’s billboard company.

Nonfamily Employees

Most family firms cannot exist by solely employing family members. Nonfamily employees are a time proven, dependable, and important part of the labor pool. Employees feel they are treated better at family firms than at nonfamily firms. In addition, the use of performance based pay, extensive selection processes, in-house training and development, employee empowerment, and job enrichment initiatives have been shown by family firms who use these practices to outperform nonfamily firms. Conversely, family firms not using employee positive behaviors do not outperform their nonfamily peers.3 The contribution of nonfamily employees can be a competitive advantage for family firms.

• All is not good news in the employment area, however. In a study of 278 small family owned business in Pennsylvania, 53% of the respondents did not have professional human resources practices in place.

• Slightly less than 25% had written job descriptions outlining responsibilities, minimum qualifications and reporting structure for each position in the business. Only 16 percent conduct formal performance reviews, and 19 percent have a bonus structure in effect.4

According to a 2015 survey, 60% of family business respondents cited recruitment of skilled personnel as their most significant challenge.5

Unfortunately, another survey shows nonfamily employees are less confident in the next generation of family leadership.6 With the important contribution of nonfamily employees to the positive performance of the family firm, professional human resource practices should be followed. This seems to be an area of opportunity for family business’s to overcome by being more professional.

Tips for Success

For a family business to succeed and advance to the next level, the following tasks have been shown to increase professionalism and business success. By instituting even some of these, a family business will go a long way toward increasing its effectiveness and chances for long-term success.

- Create the family mission statement. Why does the business exist? What is its purpose?

- Create processes to facilitate discussions (e.g., family meetings, family retreats, council, shareholders meetings, etc.).

- Create a strategic plan.

- Institute influential boards.

- Create policies and procedures that detail family members’ roles (i.e., family constitution).

- Hire nonfamily professional managers.

- Institute the succession planning process.

- Create a fair and appropriate equity arrangement that takes into consideration those family members active in the management of the business.

In a survey, family business leaders were asked the following question: “Which of the following characteristics do you think are most important for success in a family business?” Clear succession planning, shared objectives, and conflict resolution score high, pointing to the need for and importance of good, open communication:7

- Clear succession plans: 47%

- Clear and shared objectives: 44%

- Strong leadership: 41%

- Ability to resolve conflicts quickly and effectively: 30%

- Ownership restricted to family members: 26%

- Ability to take risks: 20%

- Strong governance structure: 19%

- Willingness to recruit outsiders: 15%

Appendix D lists a series of important discussion questions that should be asked of family firms and their members. These questions can help with the creation of the family constitution and can be used at family council meetings or family retreats.

What Family Business Professionals Need to Know

There are cautions for the various professionals who view family businesses as potential customers, such as family business advisors, attorneys, accountants, financial services firms, insurance firms, and small business suppliers. Suppliers can often become frustrated working with family businesses. They question why the family takes so long to make a decision, why so many people are involved, and why their decisions sometimes do not make logical business sense.

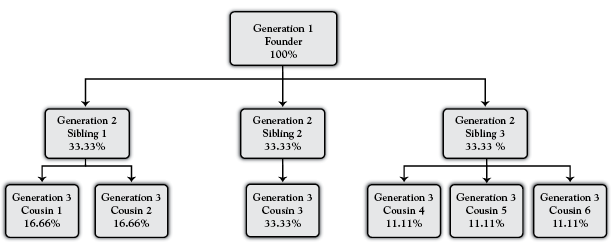

When the firm is operated by the first generation, usually a single founder with sole discretion authority, the decisions can happen quickly, with little apparent difference between this type of business and any other business of its size. In second- and third-generation firms, professionals can expect a longer decision period because multiple family members are involved. The professional should plan for delays based on the differences in goals and objectives among family members. Professionals should take notice of the number of involved family members at the firm. The decision process is slowed significantly when three or more family members are involved in the decision. Depending on the product or service offered, the decision times are usually lengthened if the family perceives the decision as expensive (or risky) when it concerns other family members or if the price of failure is high.

A tool was created to help family business professionals and suppliers understand where each family business lies in regard to decision making for various products and services (see Figure 8.1). This tool shows how each decision area increases in complexity in a fairly linear fashion, from small, everyday (programmed) decisions with one or two involved family members, to small programmed decisions with three or more involved family members, up to the larger nonprogrammed (less common, not previously made) decisions with one or two involved family members. Once the nonprogrammed decision area reaches family member involvement of three or more people, the complexity grows exponentially in an extreme nonlinear fashion.

Figure 8.1. Family business decision complexity chart.

The chart is a tool allowing family business professionals to assess the level of their customer’s firm and the corresponding action necessary to provide the firm with the required information to enable a decision.

Source: Alderson (2009).

When a professional calls on a specific family business, he or she should first understand how the products or services offered will be perceived by the business.

1. Is it a quick and relatively easy type of everyday purchase such as janitorial services or stationery, which will not involve other family members?

2. Conversely, could the family perceive it as risky, costly, or requiring a large capital outlay?

3. Would other family members want to be involved in the decision based on the previously mentioned factors?

4. Would it affect a larger number of family members than just the individual who sees the presentation?

5. Could the decision affect the family reputation in the community?

After the products and services have been analyzed, the particular family business should be assessed as to where the business decision should be located on the chart. As the level of complexity increases, the professional should be prepared for a longer decision time, the involvement of more family members, and a need for more information. If the professional cannot make a presentation to all family members, then he or she must depend on the family business contact to disseminate the information to all concerned members. The professional may facilitate this process by asking what information would be helpful to other family members, by providing multiple copies of brochures or documents, and by presenting a much more in-depth informative report, addressing as many of the family’s potential questions and concerns as possible. In this manner, every family member can be provided with the information to answer individual questions and or concerns.

In the broad search for information and knowledge undertaken by the firm as part of its decision making, the professional would be well advised to provide an abundance of information, bordering on the minutia. Such abundant information may provide the family the sense of comfort they need to collect as much information and knowledge as possible. Previous customer recommendations, testimonials, guarantees, warrantees, known business associates, and conversations with or special attention from key company executives can all help to enable the family business to reach a knowledge comfort level. By understanding the history, makeup, and structure of the family business and its key decision makers, professionals can adjust their proposals and provide more information in order to increase the family’s knowledge and comfort level, thereby helping involved family members make a knowledgeable decision. Additionally, the professional can become a more valuable resource for his or her customers. Such value may increase business within the family business area, gaining a competitive advantage over those competitors without knowledge of family business decision making.

One sibling partnership (composed of five owners) I consulted with in Southern California was carefully reviewing the specifications for a multimillion-dollar piece of machinery after previously buying similar machinery that did not perform as promised and experiencing years of an expensive legal battle. Is anyone surprised that the firm’s owners requested a personal conversation and guarantee with the president of the machinery manufacturer? This was the final piece of information the family needed in order to feel comfortable with their purchasing decision. The machinery firm thought it an odd request. However, it is not odd when the background information is reviewed:

- There are 5 second-generation family decision makers.

- All worked in the business.

- The founder is still involved.

- The previous machinery purchase almost crippled them financially.

Businesses that target family firms and have a thorough understanding of their potential client’s needs, wants, and lengthened decision process may develop a significant competitive advantage. (Yes, the president’s meeting sealed the deal, and the family made the purchase.)