The ability to carry on a successful intergenerational transfer of ownership and leadership (succession) is by far the single most important family business issue. It is also the most researched topic in the area of family business. Most family businesses do not have a successful transition of ownership from the founding generation to the second generation. Studies have generally agreed that approximately 30% of businesses transfer to the second generation, while only 10%–15% successfully transfer from the second generation to the third generation.1 Only 4% manage to stay in the same family in the fourth generation.2

The majority of family firms want to keep the business in the family and pass it on to the next generation. The American Family Business Survey (2002) found that 85% of the firms surveyed wanted to continue with family ownership.3 The Laird Norton Tyee Family Business Survey4 found that 55% of the senior generation wanted successive generations to take over and almost 85% of the family businesses that had chosen a successor selected a family member to carry on the business. Succession has often been called the final act of greatness. How ideal for a family business founder to have his creation live on long after he or she is gone: That is a legacy.

One survey reported 77% of failed family businesses that declared bankruptcy did so after the death of the founder.5 A family-owned business is more likely to fail due to lack of a succession plan upon the founder’s illness or death than for reasons having to do with competition or market forces. Many family business researchers agree that the primary underlying reasons for failed successions are a lack of effective decision making and a lack of proper planning. Often this decision not to plan is caused by an owner who cannot concede power or will not tolerate a reduction in personal authority, responsibilities, or control.

The reasons for this scenario are numerous and can be quite complicated from a psychological perspective. Often, the previous generation simply does not want to be put out to pasture. Especially if they are the founders of the business, they often feel the company is their baby and their identity is closely interrelated with the company. Others equate retirement with death and simply do not want to discuss the issue. Of the CEO respondents to a large nationwide study, 13.4% reported they would never retire.6 This causes much consternation in the family, especially the next generation members. The next generation waiting in the wings wonders when they will ever get their chance to lead.

Awareness of the life cycle stages becomes apparent when first initiating conversations regarding succession. Research has shown that at certain ages, the relationship of the founder and the successor can be either rife with conflict or relatively smooth. This is especially relevant in a father-to-son generational transfer. When a founder is in his relatively young 40s and 50s, and the successor is in his 20s or early 30s, the role conflict can be at its worst—and most visible. The current familial roles of each family member in their respective life cycles present barriers to effective communication and to efficient working relationships. Conversely, if a founder is in his 60s or 70s and the successor is in his 40s, the competition and conflict is less, producing a more positive working relationship.

An interesting discussion concerns the fact that many business researchers describe succession as the sole measurement of family business success. If a family business did not have a successful succession to the next generation, it would be considered a failure. However, if the goal of the firm was to work with family and build wealth, and they decided to capture the value of the business through an outright sale, why should that be considered a failure of the family firm?

Families have many reasons for not passing on the family business to future generations. Some of them are not necessarily negative, such as the case with the creation of significant family wealth. The children or grandchildren may have been brought up with a very high standard of living: they may have been educated at prestigious universities and they might prefer a professional vocation such as law or medicine. They might also have interests in benefitting society, such as working or volunteering at a nonprofit organization instead of working in the family business. This type of situation should not be considered a failure. Does the company still exist? Are its products still available to the public? If so, then the company was, and still is, a success.

In a study of children from family firms in their first year of college, 20% wanted to be working at the family business within 5 years, 38% were planning to return to the firm “sometime,” and 42% said never. It is interesting to note that 70% of these respondents scored the firm high or very high for authoritarian management practices.7

The media is filled with stories of wealthy third-generation members who make headlines from their outrageous behavior and spendthrift patterns. Based on the fact that few family firms have a successful ownership transition to future generations, there is a well-known adage that states, “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.” It refers to the first-generation entrepreneur who starts out poor, works very hard, and becomes tremendously successful. The second generation watched their parents work hard and suffer for the business, and most often, the second generation worked right alongside their parents. By the time the second generation had their children, the wealth was building as the family business achieved success. Unfortunately, the third-generation children were often brought up with a sense of entitlement, became spoiled, engaged in out-of-control spending, had a low work ethic, and eventually lost the business. The adage has some universal truth to it, as many countries have their own versions:

• In Italy, it is stated this way: “Barn stalls, to the stars, to the barn stalls in three generations.”

• In Portugal, the first generation is pay rice (a rich farmer), the second generation is filch noble (a noble son), and the third generation is net pore (a poor grandson).

• In Mexico, it is “father/entrepreneur, son/playboy, grandson/beggar.”

• In China, the saying is “The first generation builds the wealth; the second generation lives like gentlemen; the third generation must start all over again.”

• An old English proverb describes it this way: “There is nobbut three generations atween clogs and clogs.”

• In Jewish cultures, they describe it as “rags to rags.”

• In Germany, the first generation erwerben (creates), the second generation vererben (inherits) and the third generation verberden (destroys).

Based on conventional wisdom alone, problems seem to appear by the third generation. Research has borne this out by reporting the dismal 10%–15% succession rate to the third generation. Upon careful examination of long-lived family firms, some techniques have been successful in keeping control in the family’s hands. For instance, Japan has the oldest family firms, with some of them dating back to the fifth and seventh centuries. This is made possible by their practice of officially bringing a son-in-law into the family (when needed) and having him take the family name. The business can then have a successful generational transfer without passing through blood relatives or family of origin. In the 19th century, the du Pont family maintained their wealth and control through arranged marriages between first cousins, which was common for many rich families at the time.

For the leader, succession planning means asking the hard questions, such as the following:

• Are my children the most qualified to run the business? Or is an outsider better qualified?

• Which child should I choose?

• Do my children have interest in the business?

• Would the family be better off if the business was sold?

• Which children should the company stock go to? All of them? When?

• What will I do if I retire?

In planning for succession, sentimentality should be minimized and reality faced in a businesslike manner. Numerous examples that exist detail what is at stake for the next generation and the financial viability of the firm and the family. As an example of a costly succession decision, Edgar Bronfman Jr. inherited the leadership at Seagram’s (liquor) as a third-generation family member. After a costly merger into the entertainment industry with Vivendi SA, the family fortune plunged by $3 billion to $1.85 billion. The entire family has been affected by the choice of successor and his resulting decisions. The estate-planning implications of succession and tax-planning issues must be considered. Family businesses should seek professional advice from those suitably qualified in the appropriate area, such as attorneys, accountants, tax advisors, financial planners, and others.

Succession Issues

Although it may not seem readily apparent, stakeholders, including several important outside stakeholders, can have significant influences on whether the succession will be successful. In addition to the incumbent, the successor, and the family, the outside stakeholders who have influence are the customers, suppliers, bankers, and employees. If these important interests do not have faith and trust in the competency of the successor, they may pull their support, restrict their activities with the firm, or decide to withdraw their involvement altogether.

Serious dysfunctional sibling rivalries can occur if the choice of the successor were interpreted to be a result of parental favoritism or nepotism. Sibling rivalry is often an underlying cause of interpersonal conflict, one of the most serious issues a family business faces. If significant sibling rivalry is present, the business should seek help in the form of a family business consultant or from a family therapist who is experienced in business issues.

An issue that looms large for the firm’s present ownership is how to equally distribute the family wealth—which is, overwhelmingly, the family business itself—to all their children. Questions arise such as whether equal ownership of the company should go to a family member who has never worked in the business and has no interest in ever working there. This can become problematic in the future for the owner-manager who may want to expand or buy equipment. The nonworking partner may disagree because of a lack of knowledge or different values, such as the desire for a larger dividend check. One survey reported 29% were planning on providing to their heirs an equal distribution of their business wealth, 22% were going to give more to those who were employed at the firm, 6% were going to give zero to nonemployees, and 25% had not decided. Only 8% planned a sale of the firm to nonfamily members.8

When the firm is controlled by a single, dominant family, succession problems are lessened compared with the increased complexity of when there are several branches of family involved, such as distant cousins. Unless the business is very large, it may not be able to support all the family members who want to work in the business. The early recognition of an heir is best for all parties concerned, as other family members have time to choose educational opportunities and other avenues for a career.

Leaving at the right time may be the hardest decision a founder can make, but it can be the most important decision for successful and prosperous family succession. The final legacy of the founder should be to leave on top. The new generation, with their aggressive ideas, can now take over. If a founder stays too long, the strategic decision making tends to be overly conservative, which can have a detrimental effect on the firm in terms of lost opportunities. Studies showed that the longer a current owner stayed in control, the less likely he or she would voluntarily give up control. The ideal time for an owner to retire was found to be between the ages of 50 and 60, and the ideal time for a son to step in was in the 27–33-year age range.9 In this manner, the generational gender conflict that is often common between father and son is minimized.

The return of a retired former owner is not uncommon. Such individuals often look for a reason to return to power and authority, like a white knight coming to save the day. This situation is unfortunate for the new successor. If insiders see this situation as likely, employees and others may not fully support the successor’s efforts. Some may even sabotage the decisions of the newcomer in order to bring back the previous leader and return to “the way things used to be.”

Gender Issues

Research has shown that cross-gender succession, such as from a father to a daughter, is easier to accomplish than succession from father to son. The roles we each play as family members are probably the reason for this. Additional complications can arise from the ages of those involved. A considerable amount of inherent conflict is present in the relationship between father and son.

In early adulthood, the son is developing into a man and wants to prove himself, often by challenging the father. The result of this is the father can often feel threatened and resist any new ideas, even good ones, or withhold praise for positive contributions of the son. Conversely, due to the difference in roles, a father-daughter succession does not usually have those inherent conflicts. The relationship between the two is more open, the father does not feel threatened by the daughter’s growing importance in the business, and the daughter does not often challenge the father as a son would. It is a much smoother transition of leadership control. (The increase in the number of women in family-owned firms is discussed in Chapter 9.)

Practices for a Successful Succession

Succession is such a vital area of importance; it is one of the key areas in which professional family business consultants have developed specializations and expertise. It may benefit a family firm to hire consultants to guide them through the process.

A key concept in succession planning is to understand that it is indeed a process, not just a one-time event. Most often, however, succession planning does not take place until the issue is forced or until it is sometimes too late, such as when a death or a serious illness forces the issue. Proper succession planning is a significant and complex process that takes years to accomplish, even when done correctly. One of the first places to begin is the identification of potential successors and the creation of development plans for them. The candidates can be assessed at a variety of stages.

The following seven succession development stages may be helpful:

1. Positive attitude. Attitudes toward work and the family business are formed in the first 25 years of life.

2. Entry into the firm. This occurs most commonly when the successor is between 20 and 30 years old and the individual fills a meaningful position in the firm.

3. Business development. This occurs between 25 and 35 years old, as the successor is developing and creating important relationships, skills, and abilities.

4. Leadership development. This phase usually occurs between 30 and 40 years of age. Skills developed during this phase are networking, team building, and shared decision making.

5. Selection of the successor. Among the available methods for making a choice are the incumbent chooses, the outside board makes the selection, the family executive team selects, or a consensus is formed between the family executives and the nonfamily executives.

6. Transition of leadership. During the transition phase, authority and responsibility are turned over to the successor. The successor takes control of the strategic direction of the firm and develops the management team.

7. The next generation. The development of future successors should be a constant process.10

Successor Development Plan

The successor, if equipped with a formal business education, may become the leader that continues the entrepreneurial nature of the firm and leads the company to increased growth through the recognition of new opportunities, new markets, expanded product lines, and even new divisions or acquisitions. It is vital, then, to choose the successor early by assessing the skills and capabilities of the successor and then to create a plan designed to develop or shore up any areas of opportunity. Many family businesses now require family members to have a university education and an MBA to fully prepare future successors for business leadership.

Large corporations have a term called “fast-tracking,” where an identified leader is put through various divisions and experiences within the firm to increase learning, promote awareness, and understand how the company fits together. As an example, a fast-tracked employee would be given an overseas assignment for a short period of time, and then moved to operations, next to marketing, and so on. The purpose is to expose the future leader to as much of the organization as possible in the shortest possible amount of time. Many executives have reported their best learning experiences were when they were “thrown into the fire” and they had to learn something new. In family firms, it should be referred to as “slow-tracking.” The development process of family members should be thought of more as an apprenticeship because it can often last several decades.

Creating a Succession Plan

Redefining Retirement

It can be beneficial for the senior generation to begin planning a satisfactory retirement early. Many of these leaders do not want to retire, likening it to thoughts of being put out to pasture, losing control, or even dying. It can be highly beneficial for the firm if these leaders would proactively develop outside wealth and outside interests as a way of easing the transfer of leadership to the new generation. Often, family businesses can create a significant position for the retiring leader inside the firm, where the individual can act as a public relations face of the firm. The long-established contacts they have in the industry and the community are valuable assets in this position. Another option could put the founder who steps down in charge of the philanthropic arm of the family business. One Southern California printing company, now run by a five-member, second-generation sibling partnership, uses their founder mother as the public relations face of the firm at chamber of commerce events and as a de facto salesperson in the local community.

A resourceful and constructive use for the former leader is to use their acquired talents to develop new products or new divisions at the family business. Although a nonfamily business example, when Bill Gates stepped back from day-to-day operations at Microsoft, he took on the title of chief visionary. Freed from the grind of his daily responsibilities, he then had time to focus on areas of strategic importance for Microsoft. When he left that position, he focused full time on the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Although most family businesses do not have that level of charitable giving available, a smaller foundation at a more localized level could be a tremendous asset for the firm.

The danger of a poorly planned retirement is that the senior leader does not fully retire and continues to meddle in the business. This murky role confuses stakeholders, employees, customers, and suppliers regarding who is in charge, and it undermines the current leadership, which must solidify its power and authority. This is a common reason successors become frustrated and may even leave the firm, thus placing the company’s continued future in serious doubt. If the retiring leader has a positive role to be proud of, making a valuable contribution to the continuing organization, the retiring executive is more likely to enjoy the new role and improve the chances for a successful succession.

Building wealth outside the family business is helpful to aid in succession and as an insurance policy in case of disruption of the business. Over 90% of family businesses have their entire wealth invested in the company: In other words, all their eggs are in one basket. If the business goes down, the all the family’s wealth dissolves. By having outside investments and using business diversification, the family business eases the way for succession. The original leaders do not necessarily require significant payments from the succeeding generation to maintain their lifestyle, which could burden the new leadership with significant debt. One common practice associated with stepping down is for the previous generation to purchase the real estate associated with the business and then lease it back to the business, thereby providing a stable retirement income.

Estate Planning

It is not the purpose of this book to make recommendations for estate and tax planning purposes. Professionals (tax attorneys, accountants, estate planners) should be consulted. The guidelines change often. This subject matter is so vitally important, the success or failure of the business rides on successful estate planning for future generations to succeed.

The majority of family firms rely on insurance to pay the tax liability upon generational transfer. Approximately 50% of survey respondents regularly utilize the gift exclusion as an estate planning tool to gift company stock to heirs. Approximately two-thirds of other generations know the estate plan intentions in regard to company shares.11

As of December 22, 2017, the Tax Cut and Jobs Act was signed into law. The analysts are working hard to see what this means for family business owners and their families. Presently, it looks as if starting in 2018, the basic exclusion for gifts, estate, and generation skipping tax transfers has been doubled from $5 million to $10 million. After 2026, it goes back to $5 million. The annual exclusion for gifts appears to be $15,000 starting in 2018 and then adjusted for inflation.12

Many firms are forced to sell all or parts of their organization in order to satisfy estate tax requirements. For example, the Los Angeles Dodgers were forced to sell when the O’Malley family was faced with severe estate tax issues. An expense not commonly known to family-owned businesses is the total cost, and thus the cash needed, to successfully navigate a succession transition following the death of the former generation. Expenses often overlooked include CPA and attorney fees, insurance, taxes, and costs for professional advisors. The need for a business valuation is both critical and inevitable.

Family business owners often want to divide the ownership equally among all the children. However, equal ownership is especially problematic when inactive shareholders have an equal vote. If an outside shareholder’s concern is for short-term dividend maximization, the individual may tend to vote down capital outlays for expansion, diversification, or equipment, causing problems for the owner-manager in effectively growing and operating the business.

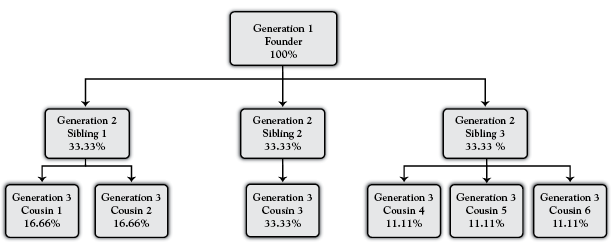

By the third generation, imbalance in ownership may occur, with a larger family having divided ownership, which gives them a smaller share of ownership per family member. Conversely, a smaller family or an unmarried or childless individual would have a significantly larger percentage of ownership and control. As shown by the Shareholder Complexity Diagram (see Figure 6.1), the founder passes the shares on to each of the three offspring equally. By the third generation, due to varying family sizes, cousin 3 has a significantly larger percentage of ownership than do cousins 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. Potential conflicts exist with this type of ownership distribution. Imagine if the family firm is successful enough to make it to the fourth generation of ownership: certain branches of the family would be significantly more powerful than others, simply due to the concentration of ownership.

Figure 6.1. Shareholder complexity diagram.

Solutions

Nonvoting Stock

One of the techniques estate planners suggest in succession planning with family firms is the creation of nonvoting stock. Inactive family members can be owners of the firm, but not decision makers in the firm. The technique has negative aspects associated with it as well, especially when a new generation of descendants of inactive family members becomes active in the family firm. Here, again, the family business should consult a specialized attorney.

Pruning the Family Tree

Studying the history of long-term successful family firms often provides visible evidence of family members or branches of the family being bought out. This technique can enable a family firm to avoid ownership dispersion by maintaining control of the business in one branch of the family. It allows inactive shareholders to turn their investments into cash and can help avoid the problem of having a plethora of owners a few generations in the future. Situations to avoid might include examples such as the sixth-generation family firm McIlhenny Co. (Tabasco sauce). The company has 145 shareholders—mostly family. The English family firm that owns Clarks Shoes at one time had over 1,000 family shareholders. The divergent motives of family members became problematic and the family narrowly averted an outright sale.13 Pruning one of the third-generation family branches shown in the shareholder complexity diagram in Figure 6.1 may be a satisfactory solution to the problem of ownership imbalance.

The pruning strategy is not without risk, however. Such actions can have the opposite effect by causing significant family conflict to the point of family members not speaking to each other. Most often, the concerns revolve around disagreements concerning the fair market value of shares. Due to the limited liquidity of the shares and the prohibition of selling stock to nonfamily members, this can be a recipe for disagreement.14

Trusts

Family firms in the United States often have the company shares held in family trusts. The purpose is to help manage the transition from one generation to the next. Estate planning, especially the financial and tax planning aspects of succession, is extremely complex. Adding to the complexity is the fact that each year changes in the tax code amend what is allowed or disallowed, new techniques are created, new rulings are made by the taxation bodies, and other techniques fall out of favor. The bottom line for family members is to have professional help in these matters. If a trust is found to be invalid, the entire estate may need to go through probate, which is extremely expensive and very time-consuming. The firm’s certified public accountant and tax attorney should be consulted and made aware of the family’s preferences in regards to succession. The estate plan should be reviewed annually and updated as necessary to ensure it is still valid and that legislative changes have not placed the plan’s success at risk.

Employee Stock Ownership Plans

Many family firms have successfully utilized employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). This tool is especially useful when a family owner does not have heirs or, most importantly, the owner wants to take care of long-term valued employees. The employees can buy in over a period of time and eventually end up controlling the firm. The owner is able to turn an illiquid asset into cash. This is an especially difficult method and must be discussed with an experienced professional.

Exit Strategies

Depending on the purpose of the family business, such as whether the intent is to pass the business on to future generations or to build financial wealth, strategic thought should be devoted to the exit strategy. The most apparent strategy is to have a succession from one generation of the family to the next. If no successor can be identified, or no family member is interested, the family may need to consider a sale to a nonfamily employee or to an outsider. This might be the time that the family firm institutes nonfamily management and steps away from day-to-day management responsibilities.

Although it is easier said than done, the most opportune time to sell the firm and thus to obtain the highest value is when the business is doing well. Many families wait until the wolf is at the door before considering a sale. By this time, it may be too late, and the destruction of wealth can be devastating to the family. This is obviously an emotion-filled topic for many families, but it should be explored at family meetings. The need to understand the goals of the succeeding generations in regard to selling the business is critical. Should a sale be considered? When? Under what circumstances? What would the process be?

One large California construction firm had a fully completed succession from the original sibling partnership to the second generation at a significantly reduced price compared with the firm’s outside value. Within just a few years, the successors sold the firm to a larger company and pocketed the windfall. Needless to say, the first generation was not pleased. It would be beneficial to assess everyone’s views and long-term goals regarding a sale of the firm.

Selling the Business

There are certain instances where the sale of the business to nonfamily members is justified: after an exhaustive search when no qualified family candidates are located or no candidates are available for development. The second scenario occurs when the business environment has changed so extensively that the firm is unable to compete or family members are unwilling or unable to invest in new technology to allow the business to compete. Family members should consider a sale of the firm rather than allowing the business to limp along toward a slow death. The family investment and wealth can be saved rather than lost due to the family’s inability to face the inevitability of business failure.

If the family has decided to sell the firm, it can often become an extended process in order to obtain the highest value. The financial reports should show increasing sales and they need to be accurate for a minimum of 3 years (ideally, 5 years). This can be problematic, as many private firms’ lavish perks on family members, such as expensive company cars, technology products (e.g., computers and cell phones), travel, restaurants, entertainment, clothing, and personal and professional services. Justification for these purchases is often tax minimization (as these items can be written off as a business expense rather than be given to the owners in the form of salary or income). The vast majority of private firms practice highly aggressive tax minimization strategies. The financial reports then show the business to look less profitable than it actually is, which has the effect of lowering the firm’s value to potential outside purchasers. Extensive time, up to several years, may be required to make the needed changes from a tax minimization strategy to a sale maximization strategy.

The valuation of the firm is a technical undertaking. The firm’s accountant will be involved, as will its attorneys and, more than likely, an outside business brokerage firm, who will represent and promote the firm to possible interested parties.

The Role of the Spouse

Since the majority of family-owned businesses are male dominated, this section discussed the important role that a wife or female partner has in the business. However, family firms owned by women are increasing; the spouse may now increasingly be a male. The spouse has usually taken on the role of chief caregiver to the family’s needs at home, allowing the marital partner to concentrate on running the business. Because of this role, the female spouse has been given the term CEO (chief emotional officer). The spouse plays a necessary and vital role in the healthy functioning of the family. If the children are fighting with each other or angry with their father, the mother often listens to the issues and, if needed, mediates. Spouses may broker discussions or use their influence on their spouse to provide awareness of situations within the family that may have an adverse impact on the business and thus the extended family. It is for this reason the spouses should be welcomed at the family council and at all other family meetings.