3

LOVE

One of the world’s first leadership scholars was a man named Valerius Maximus.1 We’re going to spend a bit of time with “ValMax” (as he’s affectionately known by classical historians) since he offers us language and ideas that are remarkably relevant to challenges of empowerment leadership. We’ll travel back to ancient Rome, but return to the present tense—and your own patterns as a leader—in just a few pages.

As far as we can tell, ValMax was on a mission. Troubled that only the elite got the chance to study leadership, ValMax began drafting his famous books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings in the late twenties CE.2 The advice he offers in these texts is sweeping and practical—including pro tips on parenting and friendship—but he is particularly interested in teaching the rest of us how to become good magistrates and military officers. Think of him as the leadership guru of the Roman people, the Stephen Covey of the ancient world.

ValMax has a lot to say. He extolls the virtues of being “severe” and hard-hearted when circumstances demand it. A leader must be willing to exact a high price for bad behavior, he argues, as much to punish misconduct as to warn potential troublemakers. But he also devotes an entire chapter to the “fidelity of slaves,” who have some power to determine their own destinies in ValMax’s version of history.a He seems to be using the stories in this chapter as a crude metaphor—at least to our modern ear—for the importance of allegiance to something beyond ourselves. Taken together, ValMax’s books are among the earliest written commentaries on leading a life that’s, well, not about you.

High standards, deep devotion

We were blown away when we first read ValMax, as he speaks to many of the challenges modern leaders face. For example, he teaches us the value of dropping the hammer, when necessary, as a leader, as well as the importance of loyalty to mission and people. But neither behavior on its own leads to glory, and he’s skeptical of both in their extremes. True leadership greatness, it turns out, is reserved for another ideal altogether, which he assigns the lofty label of “justice.”

According to ValMax, justice is all about balance, about embodying multiple strengths at once, even when they feel contradictory. The leaders ValMax truly celebrates are winners, of course, but never at the cost of their integrity. They refuse to lie, cheat, or use evidence gathered through nefarious means. They preserve the dignity of their adversaries and resist the spoils of war if dishonorably won.

One of the most haunting stories he tells involves a legislator who has to decide the fate of his adulterous son. Out of respect for the father, the community wants to spare the son a gruesome punishment—blinding in both eyes—but dad refuses to accept the charity. Instead, he gouges out one of his own eyes and one of his son’s, achieving an “admirable balance … between compassionate father and just lawgiver.”3

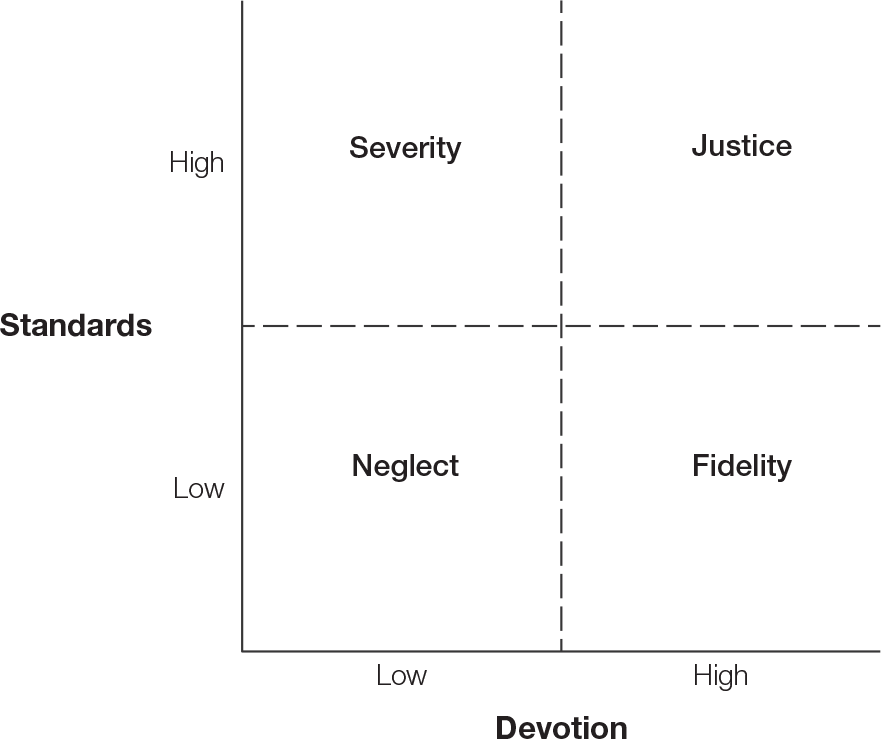

Justice seems to get much of its power from this kind of equipoise. To lead in justice means achieving a rare mix of strength and empathy, of white-hot, battle-ready ferocity blended with the cool, moderating forces of wisdom and grace. Justice is neither blindly devoted to someone else, nor so relentless in its quest for power that leaders lose their humanity. Justice neither imposes its authority at the cost of duty, nor is it dutiful at the cost of authority.

If we were to coax ValMax’s observations into a modern 2×2 framework, it might look something like that in figure 3-1, with authority on one axis and duty on the other. Leaders should aim for high marks on both ideals, embodied by justice in the upper right. They should convey both commanding authority and a profound sense of duty to their fellow human beings.

FIGURE 3-1

Valerius Maximus’s worldview

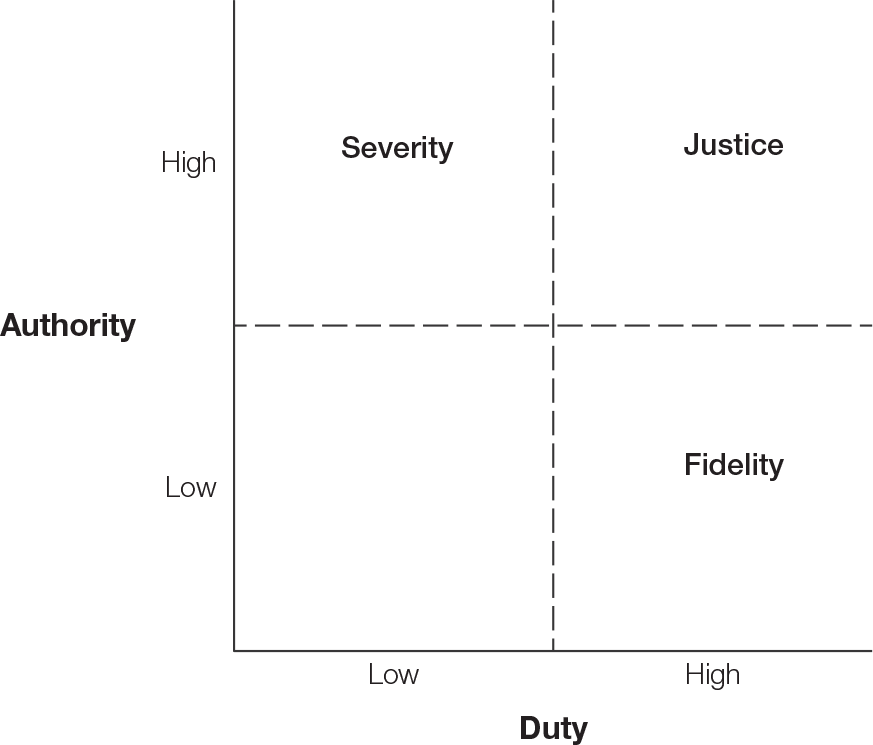

In our experience, there’s truth at the heart of this worldview that’s still resonant thousands of years after ValMax picked up his stylus. Leaders are most effective in empowering other people when they create a context we describe as high standards and deep devotion. When a leader’s expectations are high and clear, we tend to stretch to reach them. And we are far more likely to get there when we know that leader truly has our back. It’s a version of tough love that places equal emphasis on the toughness and the love. We hope to convince you, by the end of this chapter, that it’s the highest form of love.

For a very current example of what we’re talking about, watch Lisa Su in action. As the first female CEO of a semiconductor company, Su led the turnaround of Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), from the point of near bankruptcy to downright spectacular performance five years later.4 She credits the clarity of her internal communications for her success (along with her mother’s role modeling as an entrepreneur), but we see a clear example in Su of high standards–deep devotion leadership. One practical expression of this is her “5 percent rule,” which is her commitment that AMD will get a little bit better every time the company performs a task. Demanding 50 percent improvement, she believes, is too daunting (in ValMax’s language, too severe), and accepting the status quo is an unthinkably low bar. Pursuing a relentless 5 percent is exactly the right, justice-steeped balance.5

How do other people experience you?

Now let’s explore the patterns in your own leadership behavior. First, find your comfort zone on the standards-devotion matrix in figure 3-2, the quadrant where you’re most at ease operating. In this framework, we’ve tried to honor ValMax by using his language as inspiration for our four quadrants.6 Which of the four tends to be your default position? Pick the category where people are most likely to experience you, the one that feels most natural to you.

In our experience, most of us gravitate to either fidelity or severity, displaying an opening posture of either devoted or tough.7 (The psychology behind these patterns could fill another book, encompassing social norms, human development, and the biology of personality, among other rich topics.) Our conditioning would have us believe that these positions are incompatible, that there must be a trade-off between standards and devotion. It’s the rare leader who defies this trade-off, casually setting the bar high while revealing deep commitment to others. The rest of us have to work our way there with healthy doses of intention.

To develop your intuition, actually draw a blank standards-devotion matrix and put a star in your default quadrant, along with a descriptor of the people who experience you this way (for example, “my sister Anita” or “new hires”). Now populate the rest of the matrix in the same way. Under what circumstances do you leave your comfort zone? If you’re naturally in fidelity, when do you step up and bring the severity? If severity is your resting state, under what circumstances do you soften your position? Find yourself in all four quadrants and describe the patterns you observe. (See the sidebar “Discovering Your Leadership Profile.”)

Discovering Your Leadership Profile

To help you populate your standards-devotion matrix, we offer prompts below for when you may be occupying each quadrant. To be clear, there’s no silent judgment embedded in this exercise. For example, someone may need your unconditional fidelity to get through a tough experience, and severity may be exactly the right response to a willful violation of your company’s rules or values. Even neglect may have a strategic role to play in organizations with limited time and resources (more on this idea in chapter 5). What we’re getting at here are your patterns—and how they may be impacting your ability to unleash other people.

Fidelity. Who has a prized place in your life, but pays a low price for maintaining that position? Who gets what they want from you (status, freedom, extra dessert), with relatively few conditions placed on the exchange? Maybe it’s your boss or a longtime colleague with whom you’ve worked for a while. Maybe it’s someone who’s hitting their numbers but otherwise wreaking havoc. One clue to this segment is whether you regularly protect someone from hard truths such as how others experience them.

Severity. Who are you “toughening up” out there? Who gets the impatient version of you, the one-strike-and-you’re-out you, the you with little tolerance for neediness and imperfection? Maybe you’re on a mission to teach someone about personal responsibility, making up for the fact that other people haven’t held them fully accountable. Whatever the rationale, signs that you’re settling into severity include spending a fair amount of time justifying your behavior. You don’t have time to coddle anyone, right?

Neglect. Whose name do you have trouble remembering? Who have you written off as not worthy of your time and attention? You may think they don’t notice your decision to relegate them to neglect (they do). In general, a crowded neglect quadrant is a red flag for both leaders and companies, so we counsel people to find ways to empty this bucket as quickly as practical. We discuss how to do this with integrity later in the chapter.

Justice. Who reliably shows up around you as the best version of themselves, the one who’s eager to excel and grow? And how do you feel about yourself when you’re around them? This is a crucial indicator of being in justice. You feel like a superhero because, in many ways, you are one. People go higher, further, faster in your presence because they experience your conviction about what’s possible for them. When do you feel like this? If it’s rare, when have you ever felt like this?

We’re making two simple points in pushing you to find yourself in all of the quadrants. The first is that you have it in you. We all have the ability to foster a range of emotional contexts for the people in our lives. This is important when we move on to the challenge of going from one quadrant to another. There’s no place on this framework you can’t go; indeed, you’re already familiar with the landscape. Our second point is that from the standpoint of empowerment leadership, not all quadrants are created equal. If you want to unleash people, then spending most of your time in justice is much more effective than the other three options.

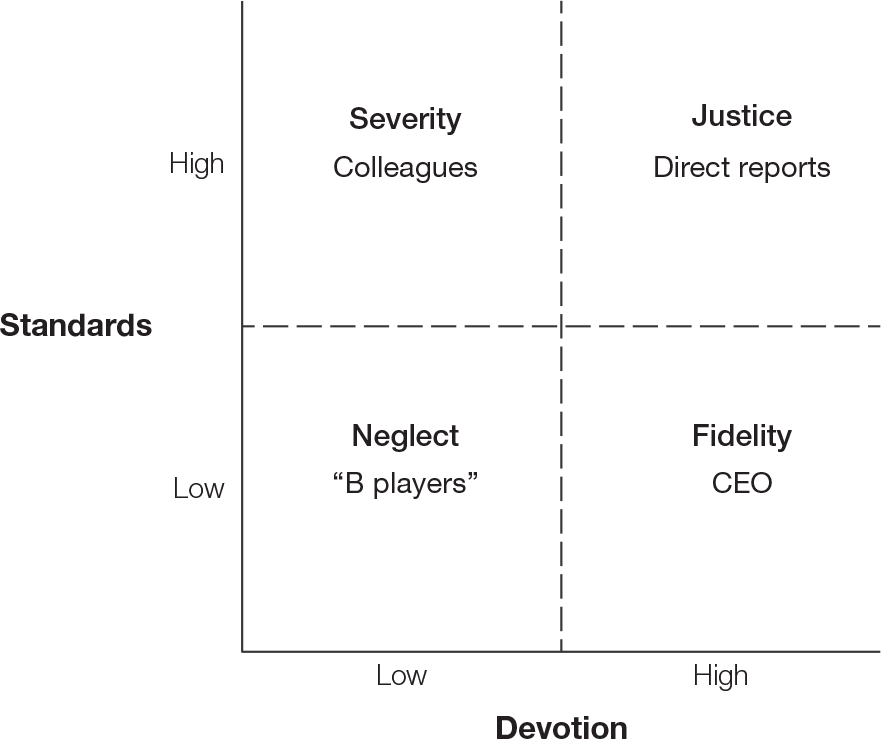

We’ve done this exercise with thousands of leaders, and a typical self-assessment looks something like figure 3-3.

FIGURE 3-3

How do other people experience you?

In this example, a C-level tech leader we were coaching (we’ll call him “John”) realized that his default position was severity. John easily set the bar high, but often held back his devotion, which had earned him a companywide reputation for being “cold.” With his direct reports, however, it was different. He was able to combine clear expectations with deep commitment, resulting in a highly empowered, high-performing team.

In doing this exercise, John realized that the reporting structure was a factor. It was part of his job description to develop his team, and the collaborative nature of the work created plenty of opportunities to reveal devotion. But the structure was a mental barrier for him with everyone else. Without an explicit mandate to develop the rest of the company, John found himself in severity. In addition, while he was loyal to the CEO to whom he reported, he also sometimes slipped into a “yes-man” relationship with her. His deference to his boss’s authority got in the way of telling her what he really thought and becoming a rigorous thought partner.

Finally, John acknowledged that he sometimes unfairly dismissed people he coded as “B players.” And while a few may have earned their exile to neglect, John’s judgment was a blunt instrument. Colleagues often shut down in response to his swift, nonverbal verdicts, even when they had something valuable to contribute.

The journey to justice for leaders like John involves resisting the gravitational pull of our leadership conditioning, the part of us that worries that if we reveal more devotion, then we’ll also have to somehow lower our standards. Nothing could be further from the truth, which we’re going to help you visualize by introducing you to Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor.

The Notorious CRP

Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor is a self-made billionaire in Peru who has played a pivotal role in supporting and enabling the country’s emerging middle class. His company, Intercorp, touches nearly every part of Peruvian life, from banks to supermarkets to schools. “CRP,” as he’s lovingly known, is the living, breathing embodiment of high standards and deep devotion. CRP sets sky-high standards, while maintaining absolute devotion to everyone in his expansive orbit.

It starts with a rigorous selection process. Interviewing with CRP is a famously drawn-out experience, comprising what feels like endless rounds of meetings, often outside the office, where he believes people are more likely to reveal who they really are. He is quick to put candidates “in the freezer” if he thinks they’re using connections to get hired. While the concept of a meritocracy has become confused in many sectors, CRP’s merit-based culture is among the healthiest we’ve observed.

If CRP does have a bias, it’s for entrepreneurial personalities who find ways to achieve more with less. He gravitates toward people who reveal hard-earned grit and a hunger to improve themselves. One year he famously rewarded his top performers with an invitation to join him in climbing a mountain near Mt. Everest. The more-senior executives purchased business-class tickets to fly in comfort on the multileg trip from Lima to Nepal. In classic CRP style, he offered a last-minute invitation to anyone flying coach to join him on his private plane for the journey, a story that spread quickly throughout the company. Everyone got the message: for CRP, status doesn’t mean access.

CRP’s most defining trait may be his unshakable belief in what’s possible for the people around him, from his colleagues to his fellow Peruvian citizens. CRP believes that human beings are the only truly competitive asset, and he invests in people with unapologetic audacity. His employees can earn no-strings-attached scholarships to top schools, and intensive education is baked into the job design of everyone on his team. Even his most senior leaders must complete rigorous coursework, and CRP expects his team to approach this work with as much intensity as the rest of their jobs. He often sits in on classes himself, taking detailed notes on his employees’ participation and then huddling with faculty to review those notes at the end of sessions. For context, we’ve taught countless classes to executive audiences and have never seen another CEO do this.

Remarkably, CRP is almost never alone, at least not when he’s working. Someone else is always by his side, typically a rotating cast of young leaders, invited to learn from direct exposure to his approach. He regularly moves people around business units for the developmental value of operating in new contexts, and he hosts an annual learning trip where managers travel to a foreign country simply to learn. The trip is designed to expose his team to how fast the world is changing, at a speed that means they’re almost always behind someone else. He describes the trip as “our annual vaccine against complacency.”

In short, CRP refuses to miss a teachable moment. One day, in perhaps our favorite example of the lengths to which he’ll go to communicate expectations, CRP purposely went to the office wearing a pair of clown bloomers under his suit pants that he revealed “accidentally.” He went about his day soberly, participating in meetings, working with his team—with red and white polka dots pouring out of his waistband. No one dared to say anything. At the end of the day, he rounded up everyone with whom he had interacted and said, “I’m now questioning whether you should be on my team.” No one lost their job, but CRP made it clear how much he valued the truth, regardless of hierarchy or power differences.

Once he’s convinced by someone’s potential, CRP is all in, particularly with people who share his values and ambition for equitable change. CRP’s goal is nothing less than the country’s economic transformation, and development indicators suggest he’s on his way.8 This development ethos comes to life at scale in his Innova Schools project, an innovative network of private, K–12 schools he designed and funded. Innova Schools deliver exceptional results at a fraction of the cost of public schools in the developed world, a business model designed to address the crisis of access to quality education in Peru. At last count, Innova had opened fifty-five schools—fifty-four in Peru and one in Mexico—serving more than forty-three thousand students. It’s now on track to become the largest private school network in the region.

The young people coming out of these schools are primed to build the future that CRP envisions. One recent Innova graduate we learned about—her dad drives taxis and mom sells pastries at the local market—saw an ad in the local newspaper about Peru Champs, a scholarship program for bright kids who want to enroll at Innova Schools but can’t afford it. The student competed with hundreds of other kids for a spot and passed with flying colors. Soon after, she enrolled at the school in Santa Clara, a low-income area on the outskirts of Lima where many families from the Andes have migrated.

At first, this young woman was intimidated by her new environment, feeling out of place in a school that charges an aspirational fee of $100 a month and caters to an emerging middle class she was far from joining. Over time, she thrived and ultimately graduated at the top of her class. She chose to apply to the best schools in the world for college, applying to institutions that could put her on a path to becoming a world-class neuroscientist. In April 2019, she became the first ever Innova Schools graduate to be admitted to Dartmouth, NYU, Swarthmore, Georgetown, Tufts, Emory, Oxford, and Stanford. Innova has offered her a full scholarship to pursue her studies. No strings attached.

CRP’s ultimate dream is to empower Peru. He believes that if the people around him, like the path-breaking Innova graduate, become strong leaders in their own right, they will invest their talent back into the country, spurring a virtuous cycle that will unleash the potential of an entire nation. He’s already seeing parts of this dream become a reality, as dynamism and activity in Peru’s most important service sectors continue to grow. Many of the leaders he has developed and launched are now building vital businesses of their own, continuing CRP’s transformative tradition of high standards and deep devotion.

Leadership in motion

Given the mission of this book, the pattern we care most about is this: most of us are not like Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor, practicing high standards–deep devotion leadership almost casually at this point. Instead, we’re often spending less time in justice than our leadership mandate asks of us. We’re sometimes creating empowering contexts where other people can succeed wildly; at other times, we’re either not helpful or making choices that undermine their ability to thrive. Our thoughts and emotions distract us from leadership. It becomes about us rather than them.

Said differently, most of us hit the justice target when it’s emotionally convenient. We embrace justice when the conditions are optimal—when we’ve slept well, or we’re not under pressure, or when it doesn’t require too much discomfort or deviation from our preferred patterns of behavior—but this convergence of circumstances rarely coincides with our biggest opportunities to lead.

The thing that will matter most, hands down, to your ability to empower others is the capacity to move into justice whenever it will make a difference. How do you achieve that level of control? How do you travel, on your terms and timeline, from severity or fidelity or even neglect all the way into justice? It’s the ultimate leadership journey and the focus of the rest of this chapter. It turns out that leaders and scholars—including ValMax—have been wrestling with this question for thousands of years.

Forget who you are

There is healthy agreement among leadership practitioners about the first step on any developmental path, which is to start by letting go of strict assumptions about who you are and, more importantly, who you are not. Get yourself into a frame of mind where you’re willing to challenge the rules you’ve written for yourself about the stark lines and limits of your identity.

As you may have discovered in the chapter’s opening exercise, identity is often more pliable than we think. When it comes to leadership, we tend to have patterns and preferences, but it’s rare that we’re truly stuck—inflexibly severe, for example, or uncritically devoted. Indeed, we tend to have it in ourselves to be everywhere on the standards-devotion matrix, to be the dismissive, apathetic blockhead in the meeting and the most inspiring general on the competitive battlefield.

Your leadership past does not define your future, and therein lies the possibility. Writing about the dynamism of circumstance and identity, ValMax urges his readers to look closely at the lives of the leaders they admire. Many had undistinguished starts in life, if not downright grim ones. But they persevered and turned challenges into gifts, pulling glory from the crucible of adversity.9

At one point, ValMax offers a startlingly modern “best self” metaphor for Sulla, a famous statesman and general and one of the most colorful characters in ValMax’s writings. Sulla’s worst self—on flamboyant display in his early years—was marked by self-indulgence and self-distraction. His disciplined best self, in contrast, delivered countless battlefield victories for Rome in the name of something bigger than himself. ValMax concludes there was a great leader lurking inside Sulla all along, just waiting to scatter the “bars … by which it was confined.”10

We all possess this type of character strength, the strength to break free from whatever leadership identities we’ve chosen to occupy in the past. It’s simply a decision about whether to use that power—and where to go with your newfound freedom.

From devotion to love

On her quest to teach the world about the merits of a “growth mindset,” Professor Carol Dweck has grown comfortable with tough conversations. She’s chosen to get in the face of parents and educators worldwide to let us know—in clear but loving terms—that we’re holding kids back with all of our good intentions. Among other behaviors, Dweck wants us to stop praising our children in ways that do more harm than good.

At some point on our journey to becoming passable parents, both starting deep in the fidelity camp, we were exposed to Dweck’s research. She advises focusing on a child’s effort (“you worked so hard!”), something within their control, rather than innate traits (“you’re so smart!”) that ratchet up the stakes of failure and undermine the drive to take risks and improve. Crucially, Dweck’s approach allows you to raise the bar without trading off a shred of devotion.11

In our worldview, Dweck is the embodiment of justice, on a mission to broadcast the price of fidelity. The punchline, of course, is that fidelity is going to cost you. To remain in a high-commitment, low-standards posture as a leader allows you to feel as if you’re in service of others, since you’re taking care of them, but it’s mostly about you. It’s a decision to trade off other people’s excellence in order to stay within the limits of your own emotional safety zone.

Dweck summarized her challenge with the following questions: Are you preparing the child for the path? Or the path for the child? Our translation to leadership is this: Are you asking your people to evolve? Or are you instead—because of loyalty or complacency or conflict avoidance—asking relatively little of them? Are you empowering others or are you making them comfortable?

If people feel supported but unmotivated around you, cozy but passive, then your path to justice involves raising the bar. Let Dweck’s prep-for-the-path challenge be your battle cry—a reminder of the Sulla within all of us, waiting to break free.

Catch them doing something right

There are countless ways to raise expectations, some more or less of a stretch for longtime fidelity occupants. The trick is to reject the flawed assumption that in order to move the goalposts, you have to give up any of that beautiful devotion.

The good news is that the most effective mechanism we know for accelerating human progress taps into our natural devotional impulses. The idea is simple: catch someone in the act of behaving exactly as you want them to behave, using sincere and specific praise. Describe the behavior in enough detail so that they can replicate it. Take it from Dweck and focus on things that a person can truly control. Rinse and repeat on a very regular basis.

The specific part matters a lot. Sincere but nonspecific praise is easier to dispense, but it rarely helps someone improve, since they’re not entirely sure how to recreate the magic. For example, telling someone they did a “nice job” after a meeting generally doesn’t help, since the recipient has to guess what they did to earn it. In contrast, telling someone, “The way you took two competing ideas and articulated what was in common between them was really effective in breaking the stalemate,” has enough detail so that the listener knows what to do more of the next time. Another word for this, of course, is positive reinforcement.

Positive reinforcement can feel awkward at first, as it’s a departure from prevailing feedback norms. (If you took our other people’s awesomeness [OPA] challenge in chapter 1, then you have a running start.) Within about two weeks of practice, however, people consistently report back to us that it begins to feel natural and also refreshingly, delightfully good. It forces you to pay closer attention to the people around you and generates a positive charge between you. You get to be the Santa Claus of feedback, handing out improvement gifts wherever you go.

Regrettably, much of the feedback culture in organizations today is downright Scrooge-like. Feedback tends to be vague and mostly negative. One particularly ineffective manager we observed had a habit of sending two-word emails that said, “not good.” Literally, that was the entire email. Not surprisingly, this behavior created mild-to-intense anxiety among her colleagues, with little hope of improving anything.

There’s still a time and place to correct negative behaviors, but we advise doing so sparingly, as it’s much less effective at spurring improvement.12 When you do have to do it, bring evidence to the discussion. Be clear about the future state you envision and the higher-order reasons for it. Whenever possible, frame the behavior change as a small pivot with a big payoff to your shared mission. Let’s call this type of intervention “constructive advice.”

For the feedback Scrooges among us, this next part is important: for constructive advice to be credible, it must be layered on top of a foundation of trust. Of course, that foundation requires empathy—the recipient’s conviction that you’re truly seeing them, both the good stuff and the bad. (If someone only sees what’s wrong with us, then we tend to process what they say as judgment rather than as fuel for improvement.) In the absence of empathy, constructive advice can easily become destructive, making the recipient worse rather than better. For example, it could make them more self-conscious in their execution or less confident in their decision making. Note that this happens all the time.

Somehow an assumption has taken hold in many companies that “real” feedback is the negative stuff, the difficult conversations that we all need to learn how to have with each other. Positive reinforcement, in contrast, is something to be tolerated suspiciously on the way to getting to all this realness. In our experience, the very opposite is true. It’s positive reinforcement that gets the job done, the most powerful accelerant we’ve observed for helping human beings scramble up a learning curve.

If you want more data, observe the training of well-behaved dogs. We suggest the legendary Pawsitive Dog training center in Boston, founded and led brilliantly by Jenifer Vickery. On any given day in the center, most of the dogs are doing things humans find difficult, such as lounging peacefully, untethered, in the presence of constant stimulation. Watch the methods of Vickery and her team closely. Are the dogs getting rewarded for good behavior or corrected for bad? At what ratios? The headline is that the dogs that are thriving are being lavished with a constant flow of food and attention, in response to very specific behaviors the trainers want to encourage. We’d argue that this approach works for most creatures, goldfish and above in biological complexity.

There’s a role for both positive reinforcement and constructive advice in anyone’s evolution, but here’s the part that surprises most people: the right ratio of positive to constructive is at least 5:1. For every unit of constructive advice you decide to hand out, the recipient should ideally receive five units of positive reinforcement. Many of the workplace cultures we’ve studied are closer to 1:5, with far more effort going toward behavior correction, only some of it constructive.

We’ve seen firsthand that a 5:1 positive-to-negative ratio is within anyone’s reach, even the die-hard constructive advice givers. If you give constructive advice once or twice a week, for example, look for daily opportunities for sincere, specific, positive reinforcement. Monthly constructive advice? Shoot for the positive stuff slightly more than weekly. And so on. You get the math. Once you get hooked on the uptick in improvement, we’re confident you’ll be converted.

How will you know if you’re getting it right? Your performance metric is someone else’s improvement. If you’re not seeing improvement, then it’s your job to try another way. Restate your observations with more specificity. Build more trust so that your recipient(s) can actually hear what you have to say. You don’t get credit for trying regardless of whether you were effective. Your job as a leader is to make others better. If the feedback you’re giving has a neutral to negative impact, then you’re not doing your job. (See the sidebar “Ten Ways to Set Higher Standards Tomorrow.”)

Ten Ways to Set Higher Standards Tomorrow

What else can you do to quickly raise the bar for the people around you? Here are some of our favorite approaches, all achievable within the next twenty-four hours:

- Make it a group project. If fidelity is your jam, one painless way to get started is to raise the collective standard. Gather your team and describe the team’s goals and the why of your new expectations. Decide together how you’ll achieve your shared goals and how the team wants to be held accountable for delivering.

- Celebrate a win. Take that positive reinforcement machine out for a real test drive. Publicly praise someone for doing exactly what you want them to do, using the magic of sincere and specific praise. Make it clear to everyone listening precisely what they have to do to get their own “Scooby Snacks” from you (our preferred term, as inspired by the rewards-motivated cartoon dog).

- Treat someone like their better, future self. Don’t just stay open to the idea that someone might one day evolve: assume they’ve already done so. Engage with a new and improved version of someone, even if they’re not quite there yet. For example, give them that stretch assignment you’ve been holding back or offer advice that only their better self can execute. Anything to signal that the future is now.

- Put your high performers to work. Ask the high performers on your team to help you raise the bar by coaching and inspiring their colleagues. This type of mentoring can take lots of forms, from group meetings to intensive one-on-one work. Give your new coaching squad the flexibility to interpret their mandate in ways that will energize them.

- Convene an after-action review. This is the US Army’s formal protocol for learning from what actually happened. Do your own version by getting your colleagues together to discuss what you could have done better as a team, even when things went well. Just the act of setting this agenda allows you to communicate that the status quo isn’t good enough.

- Set better goals. Great work is being done to codify and share the world’s learning on goal setting. Get smart about this movement and adapt it to your own context. One of our favorite tools is the OKR (objectives and key results) system used by Intel, Google, and others. And if you want to get started even faster, consider taking the SMART approach, which calls for goals to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time bound.

- Broadcast your ambition. Tell everyone around you what you’re trying to achieve, at a level of detail that makes sense for the relationship. Make your audacity and sense of purpose infectious. If recruiting accountability partners will help you succeed, then don’t be shy. Find a peer (or two, or three) to keep you honest.

- Eliminate an inefficiency. Make it clear that time is too valuable to waste. Discover what people dread doing and reduce their pain. Easy wins in most organizations include streamlining reporting and optimizing performance reviews, but stay humble and curious in this process. Assume you don’t know everything that’s draining your team’s time or all of the latest tools that could help.

- Take bold action. Take immediate, meaningful action toward a personal or team goal—the bolder the action, the better. Ideally, do something you’ve never done before, something that surprises even your closest colleagues. Make it clear that beliefs and norms have changed, starting with you.

- Be the standard. Model the standards and behaviors you want the people around you to adopt. Be impatient with your own mediocrity and don’t let yourself off the hook. If you find yourself slipping, take a timeout from the leadership path. Spend some time recovering until you’re back on track.

From expectations to love

Some of us are most comfortable as leaders in severity. If that describes you, let’s assume you got there for good reasons. Revealing high standards but minimal devotion might serve a productive, short-term purpose for the herd (e.g., making a negative example of someone), but for a leader to stay there is a pricey choice for most teams.

Like the trade-offs associated with fidelity, to stay in severity is a decision that’s driven primarily by your own needs, particularly the need for control and security. Severity can meet these needs, at least provisionally, but its upside is limited. Other people tend to give you what you ask for, but rarely much more than that. They exert just enough energy to avoid feelings of failure or shame or whatever your management weapon of choice may be, but it’s often too risky around leaders in severity to innovate or deviate from expectations (even if it’s to exceed them).

The counterexample, some would argue, is Steve Jobs. At times notoriously severe as a leader—arrogant, bullying, impatient—Jobs built the most sustainably innovative company of the last century. But we don’t see Jobs as a severity success story. From our perspective, Jobs was at his most effective when he paired high (if blunt) standards with unflinching devotion to the potential of his team. He regularly empowered the people around him to perform superhuman tasks, and they responded with fierce loyalty, even at the height of the war for tech talent. Debi Coleman, an executive on the team that launched the first Macintosh, summarized the feeling of many of his top lieutenants: “I consider myself the absolute luckiest person in the world to have worked with him.”13

One of our favorite Jobs anecdotes is recounted by Walter Isaacson, who wrote the definitive biography of the iconic leader. He tells the story of Jobs trying to get the glass on the first iPhone right, which he believed the company Corning had the ability to manufacture. Jobs flew to meet with the CEO of Corning, Wendell Weeks, who informed him that his request was impossible, certainly in the time frame Jobs needed, since Corning hadn’t made the glass since the 1960s. “Don’t be afraid,” Jobs replied, to a fellow corporate titan he hardly knew. “You can do it. Get your mind around it. You can do it.” An astonished Weeks figured out how to retrofit his Kentucky factory and delivered the glass in under six months. To this day, the glass on iPhones and iPads is manufactured by Corning.14

In this exchange with Weeks, Jobs made the fundamental choice that all leaders have to make, to choose “me” or “you” or, in our worldview, to choose fear or love. Instead of dismissing Weeks, he made him feel like a hero, someone capable of achieving the impossible. In our experience, this is not as hard as it sounds. Many leaders already are deeply devoted to the people around them; they’re just not effectively communicating that devotion. They’re rooting for their people in the quiet—and safety—of their own hearts, keeping their humanity to themselves, where it isn’t doing anyone much good. The journey from severity to justice is often about finding ways to reveal your true commitment. There are innumerable ways to do this, and we call out some of our favorites in the sidebar “Ten Ways to Reveal Deep Devotion Tomorrow.”

Ten Ways to Reveal Deep Devotion Tomorrow

The following are ten things that you can do to communicate commitment to the people in your life, all achievable within the next twenty-four hours:

- Again, put down your phone. In a world of relentless, device-driven distraction, giving someone your undiluted attention is among your clearest devotion signals. Use your devices as they were meant to be used, to get closer to people at a distance instead of further away from the people right next to you.

- Channel your inner Terry Gross. Get curious about the lives being lived around you. Why have your colleagues made the choices they made? What has surprised or delighted or disappointed them along the way? If you’re stuck for how to begin the conversation, kick things off with the a line favored by iconic public radio host Terry Gross: “Tell me about yourself.”15

- Experience their reality. Assuming you know what your colleagues do all day is a fairly common severity stance, along with concluding that it’s probably not the right things. Find out the truth with active inquiry or even some good, old-fashioned job shadowing. If they’re spending their time in ways that are indeed less than optimal, help them to prioritize better.

- Ask how you can help. Find out how to be of service to someone. Don’t muddy the agenda with other things on your to-do list; keep the conversation focused on how you can help someone achieve something meaningful. And don’t end the conversation until you’ve committed to take action in ways that improve their chance of success.

- Proactively help (without the asking part). Pick someone on your team whose proverbial “plate” you know well (ideally, because you’ve piled things onto it) and surprise them by removing something. Show them you get it by choosing something that’s causing particular frustration and/or is misaligned with their long-term goals.

- Offer snacks. Feed people, preferably something they actually want to eat, but even a surprise box of doughnut holes will do the trick. To feed someone is to acknowledge their presence and humanity at the most foundational level. An edible offering can be wrapped in all kinds of packaging—celebration, gratitude, sustenance for a hard night ahead—that transforms easily into the currency of devotion.

- Give them a break. The research is clear that sprints only work when they’re combined with time for recovery. Protect the space for real recovery for people, especially those who think they’re the bionic exception, who think they can keep going indefinitely without stopping to rest. It’s even simpler for those who report to you: make it non-negotiable and send them home for the day (or longer).

- Acknowledge their lives outside work. Recognition of someone’s multidimensional existence can show up in many forms, so, no, you don’t have to feign interest in their toddler’s Spiderman-themed party. Instead, you can simply operate under the assumption that they have a life outside work by minimizing evening and weekend work. This is particularly meaningful to women, who are more likely to be primary caretakers of children and aging parents.

- Offer sincere, specific gratitude. Thank someone for doing something that truly made your life better. Be specific about the act and its effects, how their decision made a difference. For a bigger devotion bang, send a thank-you note or another tangible expression of your gratitude. There’s no shame in being unoriginal here. “Stop with the flowers,” said no one ever.

- Less me, more we. Language matters, in ways that can shape—and reshape—our realities. As a starting place, check the number of “I” and “me” statements you’re making over the course of the day. Replace a healthy percentage of them with “we” and “us.” For bonus points, throw in more “you” and “yours,” as in, “How can we help you achieve your hopes and dreams?”

From neglect (all the way) to love

When you find yourself in neglect, you essentially have two choices: invest in the relationship or respectfully sever it. Staying in neglect with people is generally a toxic choice, for you and everyone else. There is such a thing as benign neglect, but it’s a high beta strategy, as likely to produce disastrous outcomes as positive ones.

One pattern of neglect we see is the subconscious decision to disregard someone who needs to be separated but is still in the ecosystem. As creatures of feeling, we often insulate ourselves from the discomfort of the separation process by dehumanizing a person, sometimes even in small ways like reduced eye contact. See the sidebar “How to Respectfully Fire Someone” for a broader discussion on how to terminate someone with integrity, which it will not surprise you to hear, requires a move into justice.

How to Respectfully Fire Someone

Over the last decade, we have worked with countless senior executives, many of them in challenging circumstances. Regret is rarely their primary emotion, but when it does show up, it’s almost always regret at not moving fast enough to do something they knew was right for their business. In the vast majority of those cases, the thing they waited too long to do was to let someone go who was no longer right for the company.

The ability to quickly and gracefully part ways with employees is among your most important tactical leadership skills. Here’s our advice for how to do it with high standards and deep devotion for everyone involved:

Recognize the pain of the status quo. Start with a full and honest accounting of the costs of inaction. Most leaders are aware of the downside of an underperforming employee (for example, their impact on performance or culture), but they underestimate the upside of having the right person in the role. What would true excellence in this function do for your team or company? How would it change your business?

Preserve their dignity. Anyone getting fired is going to feel some pain, in most cases, emotionally and financially. Protect their dignity however you can, from the timing of the discussion, to the separation package, to the exit protocol you follow. If you can avoid involving security, please do. Somehow it became standard practice to make separated employees feel like criminals, and yet rarely does the retaliation risk justify the humiliation we extract on their way out the door.

Do it yourself. Do not outsource the discussion to someone else on your team. Your people are paying close attention to how this goes down, and it’s a chance to send clear signals about accountability and values—both the company’s and your own—and to also make sure the person being separated is properly supported. Those opportunities can be easily squandered if you’re not in the room.

Commit to their future success. Be honest about your decision and consider framing it in ways that help them find their next opportunity. Give them the organizational context. Thank them for the contributions they did make. Everyone stumbles at some point in their career, and in most separation cases, there’s no reason you can’t play a role in helping them get back up. There may be complicating factors, but whatever the situation allows you to do, be generous.

Honor everyone else. Make sure the team members that stay behind are getting sufficient attention. What does your decision mean for them? What conclusions should they draw from it? Although some tension may be healthy at this point, have a plan for reducing unproductive anxiety. Answer whatever questions you can, quickly and ideally in person. Then get your legions back out on the battlefield, focused on advancing the larger mission.

The path from neglect to justice can feel like a long one, but like many of the choices that transform our experience, it can be traversed in an instant. It turns out the decision to see someone takes no time at all.

By any other name

We were originally going to name this chapter “Tough Love” but decided simply on “Love.” The gift of helping someone reach for a better future than the present they’re living is among the purest forms of human love we know. It’s certainly the one that gets us up in the morning.

Part of the reason we use the word “gift” is because it’s not free: to make others better comes at a price for the giver. As we’ve explored throughout this chapter, there’s no path into justice that doesn’t involve some amount of tension for you as a leader. When you’re doing this right, when you’re making the kinds of changes that enable other people to thrive, you may feel as if you’re out over your skis at some point. Our message to you, to all of us, is to tuck your head and keep going. Get comfortable with the discomfort. The payoff is a force with enough power to unleash other people, a force conventionally known as love.

And whenever you’re ready, move on to the next ring of empowerment leadership: belonging. This is where you get to empower not only individuals, but also the unit of teams, ensuring that everyone can contribute their unique capacities and perspectives. It’s where diversity and inclusion create the path—the freeway, more accurately—to truly exceptional performance.

GUT CHECK

Questions for Reflection

- What do other people tend to feel when they’re around you? What do you want them to feel?

- Where do you naturally find yourself in the standards-devotion matrix? Which quadrant is most comfortable for you?

- What do you need to do differently as a leader to consistently occupy the justice quadrant? To reveal high standards and deep devotion simultaneously?

- What makes doing the work to be in justice worth it to you? What will change when you can reliably set other people up to thrive?