5

STRATEGY

The first frontier of absence leadership is strategy. Strategy, done well, empowers organizations by showing employees how to deploy the resources they control (time, focus, capital, etc.) in the absence of direct, hands-on leadership. This scale of leadership depends on people understanding the strategy well enough to inform their own decisions with it. In our experience, too many companies are held back by strategic confusion below the most senior ranks. Said differently, strategy guides discretionary behavior to the limit of how well you communicate it. This chapter is about removing the artificial limits.

It starts with getting the strategy itself right. In the first part of the chapter, we walk through a framework for designing strategies that delight customers, protect suppliers, and deliver healthy returns to both shareholders and employees. We like the term “value-based” strategy because it focuses on where value is created and captured. But we also reject the idea that strategy is simply a series of technical decisions. We believe that strategy is a direct extension of who you are as a leader. Strategy embeds your own values and beliefs into your organization’s behavior. It carries who you are into corners of the company you could never reach on your own. Our challenge to you is to use that superpower to unleash the potential of, well, everyone.

What is strategy?

At its most basic, strategy describes how an organization wins. The component parts of strategy vary by industry, but the key inputs are typically customers, competitors, and suppliers—the external stakeholders whose decisions can make or break you.1 We’ll reveal up front that we’re going to make the controversial choice to put your employees on this list, too. More on that heresy later in the chapter.

Your first job as a strategist is to be better than your competitors at the things that matter most to your customers. This sounds simple enough, but here’s the thing: in most cases, this means you’ll also have to be worse than your competitors at other things, ideally the less important ones. A major lesson of our decade of research on service companies—we wrote a book about this idea—is that organizations that resist and try to be great at everything usually end up in a state of “exhausted mediocrity.”2 Sound familiar?

Here’s another way to think about it: one of your central duties as an absent leader is to empower your employees to deploy resources they control without you staring over their shoulders. They could distribute these resources equally, across all potential sources of competitive advantage, but we advise you to help them place those bets more strategically. In particular, we suggest underinvesting where it matters least in order to free up the resources to overinvest where it matters most. We propose being bad in the service of great.

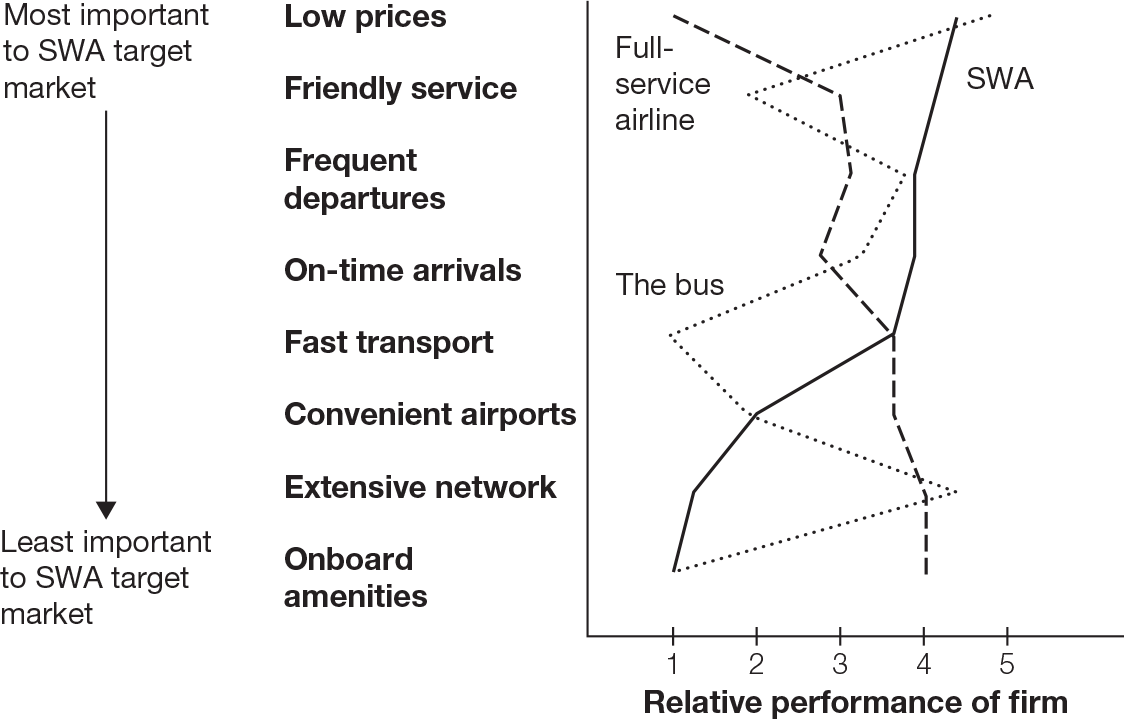

A leader who embraced this part of his job was Herb Kelleher, the iconic cofounder and CEO of Southwest Airlines, which remains an exception to the rule that airlines have to lose money and make their customers sad. On the graph in figure 5-1, the attributes ranging from most important to least important for Southwest’s target customers are arranged on the vertical axis. For clarity, we call these strategy graphs attribute maps.3 On Southwest’s attribute map in figure 5-1, low prices mattered most to Kelleher’s target market, with friendly service in the number two spot. At the bottom, an extensive network and onboard amenities mattered least.

Attribute map for Southwest Airlines (SWA)

Source: Frances Frei and Anne Morriss, Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012).

Under Kelleher’s leadership, Southwest became best-in-class on the attributes that mattered most to its customers precisely because it chose to be worst-in-class on the ones that mattered least. The airports Southwest operated out of were in inconvenient locations (for example, its Washington, DC, hub was in Baltimore), but that meant lower costs for the airline, savings it could pass on to price-sensitive customers who were more than willing to give up convenience in return for cheaper tickets. Southwest denied passengers any meaningful onboard comforts (including an assigned seat!), which meant it could turn planes around faster at the gate, which meant that the airline got more flying time out of its expensive, airborne assets than its competitors, freeing up even more room to lower prices—the thing its customers wanted most.4

These kinds of decisions take real courage, particularly for the leaders among us who do not like to let anyone down. Kelleher once famously received a complaint letter on behalf of an angry grandmother about Southwest’s policy of not transferring bags to other airlines.5 The letter asked for the simple courtesy of transferring her luggage on her way to visit her grandkids. In Kelleher’s response—a story he shared far and wide, using it as a teachable moment for the organization—he pointed out that Southwest’s business model wouldn’t survive if he reversed this policy. If his team had to pause in their turnaround sprints to deal with the complexity and uncertainty of another airline, then Southwest’s turnaround advantage would disappear. So Kelleher was very sorry, but he would not be transferring anyone’s bags anytime soon.

We love this story, enough to repeat it here, because we can imagine how hard it would have been to say no to this perfectly reasonable woman, making a perfectly reasonable request, representing countless other perfectly reasonable customers frustrated by Southwest’s anomalous policies. It would have been strategically excruciating, on one level, to deny her a basic service that every one of the company’s cutthroat competitors offered. But in return for this kind of discipline, Kelleher got to build the most successful airline in history.

Dare to be bad: Leader’s edition

Whenever we teach people about companies that underachieve on some dimensions in order to excel on others, we get the same question: Does this logic work for people, too? The short answer is absolutely. Our male colleagues on the promotions fast track in chapter 4—the ones who were submitting papers before they were perfect—were making this kind of professional trade-off intentionally and strategically. They were choosing to deliver lower quality at the beginning of the review process in order to improve faster and produce exceptional results later on. Bad in the service of great. Meanwhile, our female colleagues who were striving for perfection at every stage of the process were more likely to end up with lower output.

The most successful leaders constantly make trade-offs like these, often describing their workdays as relentless exercises in prioritization. They accept that they can only do some things well, and so they choose to do the most important ones. Patty Azzarello became the youngest general manager at HP at thirty-three, ran a billion-dollar software business at thirty-five, and became a CEO at thirty-eight. Reflecting on her exceptional career and the patterns of effective leaders around her, she observed that “the most successful people don’t even try to do everything.” They apply “ruthless prioritization,” in Azzarello’s words, while the rest of us become “famous for working hard instead of for doing important things and adding value.”6

The potential payoff of a dare-to-be-bad mindset can be easiest to envision in a one-on-one relationship. Here’s an exercise you can do at your desk: pick a person in your life with whom you want to build a stronger connection. Maybe it’s your boss or your partner or even a loved one at home. Consider the following trade-off: What if Super You showed up when it mattered most to them, but it meant that Average You—or even Bummer You—showed up when it mattered least? How would your relationship change as a result? What about your effectiveness or mental health?

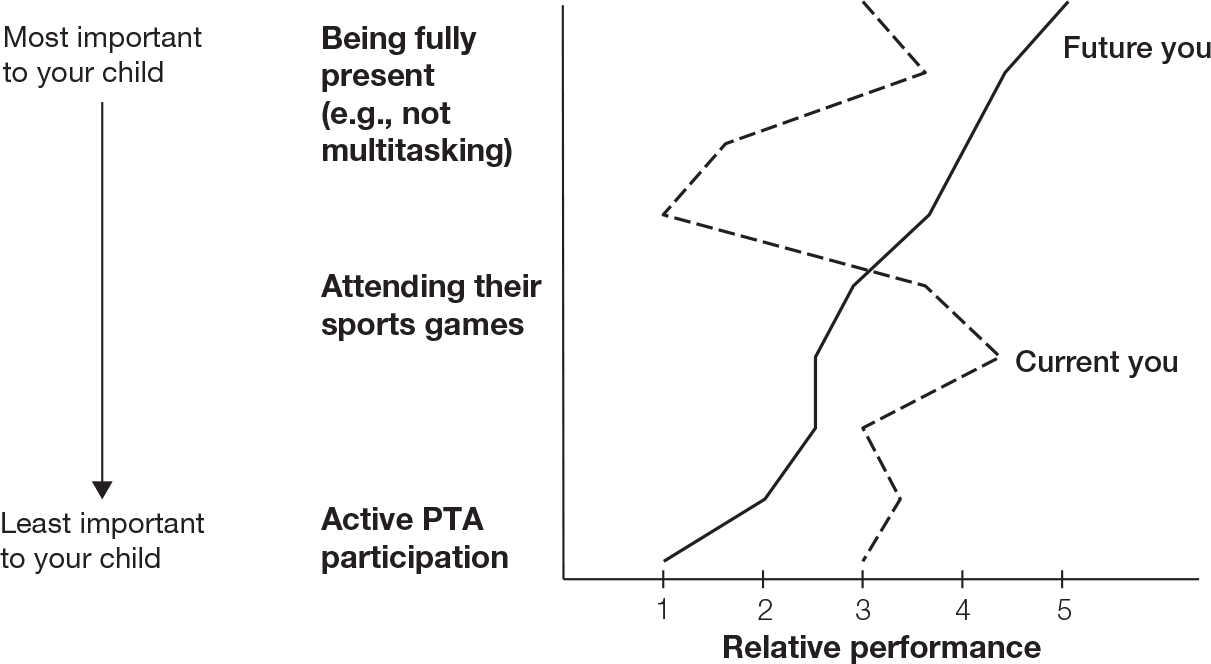

Play this out with us on an attribute map. For the person you’ve selected, rank the activities you share and/or the things you do for them, from most important to least important. Now give yourself a grade on your current versus optimal performance, some reasonable notion of excellence, 1–5, with 1 being terrible and 5 being outstanding.a

Most people end up with a line that looks like the dotted line in figure 5-2. In this example, being fully present in the time you spend with your child is the thing that matters most to them. This means that you’re not on the phone when you’re at home, not thinking about a work problem in the middle of a conversation about whether Hulk or Superman would win in a matchup, and not secretly checking email in the bathroom when you’re supposed to be building Legos. (These are purely hypothetical scenarios used for educational purposes only. Obviously.)

What matters less to this hypothetical child is your regular attendance at PTA meetings. A dare-to-be-bad response to this kind of insight might be to give up the PTA commitment and invest that additional time into making sure you’re not bringing work home from the office. Or it might mean redirecting your school volunteering time from PTA events to the sports program, a space where it is meaningful for you to be active and visible. Again, the idea here is to be bad, to be downright dreadful, at the things that don’t matter in order to be excellent at the things that do. This takes courage and a willingness to give up the fantasy of unlimited capacity. In return, you get to create the space to truly thrive.

Which brings us back to the mission of this book. What we’re describing here are the types of personal and professional trade-offs that make great leadership possible. One thing that doesn’t get a lot of attention in the leadership discussion is a frank acknowledgment that it takes tremendous energy to do it well. Building trust, maintaining high standards and deep devotion, unleashing the potential of more and varied people: these are nontrivial challenges. If you want to excel at them, do us all a favor and please be bad at something else.

Create (a whole lot) more value than you capture

Once you determine how to create value by strategically winning and losing, it’s time to capture some of that value and build a business.7 Price is the central mechanism that allows you to do that, the knife that divides the value cake between you and your customers. And so your next strategic challenge is to figure out how to price that dare-to-be-bad, attribute-infused, product-service feature bundle you’ve strategically designed. For simplicity, we’re just going to call this your “product.”

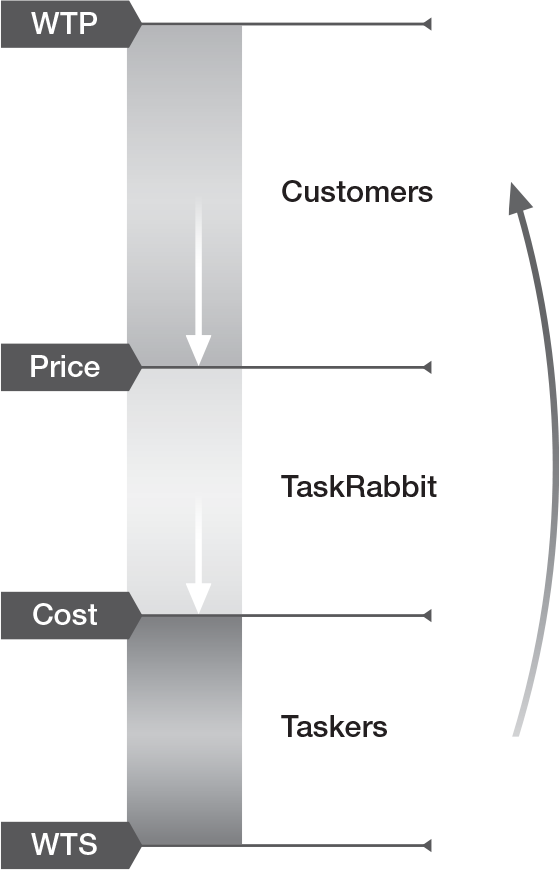

Pricing tends to work better if you understand your customers’ maximum willingness to pay (WTP) for a product. In order to attract customers and stay in business, your price should live somewhere between WTP and cost. If your price is higher than WTP, even a penny over, then your customers will walk. If your price is lower than cost, even a penny lower, then you’re losing money rather than making it, threatening your existential lifeline as a business.b We suggest visualizing your pricing decision on a continuum like the one in figure 5-3.8 Everything above price but below WTP benefits the customer, so we call this the zone of customer delight. Everything below price but above cost benefits the company in the form of firm margin (the zone of CFO delight).

Where should you draw your price line? This decision is often a source of great debate. It usually starts with someone arguing to set price as close to WTP as possible in order to maximize profit and preserve company viability. This perspective is usually followed by more moderate voices that argue to set price somewhere in the middle, between WTP and cost. Eventually, the customer champions jump in with passionate justification for even lower prices (typically above cost, but not by much) in order to attract more customers and make up for low margins with volume.

These debates are often passionate because there’s no universally correct answer. The argument for maximizing profits is perhaps obvious, but it can also be good business to leave enough room on the value range to delight loyal, buzz-generating customers. Apple’s pricing strategy is a good example of this approach. Apple deliberately prices its products below its customers’ sky-high WTP (but still well above cost), generating a form of customer devotion that approaches frenzy.9 Despite paying a handsome price premium by industry standards, almost everyone leaves an Apple store feeling like a winner. Meanwhile, Apple’s profits continue skyward.

Our practical advice is to be like Apple and aim for the middle of the value range, even if you’re competing for a segment of the market that’s not particularly price sensitive. Great products are built on enduring stakeholder partnerships where companies and customers are increasingly rewarded for the ride they’ve decided to go on together. Even if it’s counterintuitive, leaving value on the table for customers is a way to compensate them for doing their part. It’s an expression of trust, love, and belonging, all wrapped into that transactional moment of truth.

This idea is also at the heart of one of our favorite leadership maxims: create more value than you capture. Legendary entrepreneur and open source pioneer Tim O’Reilly has been challenging tech companies with this phrase for the last few decades.10 We think this advice is a clarifying principle for anyone building any organization, and certainly anyone seeking to lead one.

All this is to say that price is not simply a technical decision you make with your strategy team, informed by what you can get away with. It’s also a proxy for your commitment to be in service to your customers. You’re in this together, and the price of doing business with you should reflect that truth.

Looking at leadership through a value lens, the responsibility of a leader is to create value for others. You will of course want to capture some of that value for yourself, but the capturing part is not about leadership. Capturing is about survival and security and wealth creation. We make no attributions about those pursuits—indeed, they are necessary—but we want to be clear about the distinction. You create value as a leader, and then capture some of it as an individual. And so our modification to O’Reilly’s challenge might be to get out there and create a whole lot more value than you capture.

Enter your suppliers

At the other end of the value spectrum are your suppliers. Suppliers are the people and organizations providing things like labor and raw materials and office space, the sugar and eggs to the value cake you’ve now so thoughtfully sliced up and shared with your customers. The size of that cake of course depends heavily on how much you pay your suppliers for their inputs. The less you pay, the more cake you’ve got, and vice versa.

So how much should you be shelling out? Just as pricing works best with an understanding of customer WTP, costing works best with an understanding of supplier willingness to sell (WTS). WTS is the lowest amount a supplier is willing to accept for their goods and services. If the amount you offer is lower than your suppliers’ WTS, even a penny under, they’ll walk. Everything between this minimum WTS threshold and what you ultimately pay (your cost) represents supplier surplus. In figure 5-4, we add these additional variables to the mix. In its full glory, this framework is called a value stick.

Strategic value stick

Source: Adam M. Brandenburger and Harborne W. Stuart, “Value-based Business Strategy,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 5 (March 1996): 5–24.

To review, the lower you can get your costs, the more value there is to distribute between you and your customers. So should you squeeze your suppliers to reduce cost as much as possible without crossing their WTS threshold? Large retailers and major players in the auto industry are notorious for this approach, and you will find lots of reasonable people telling you it’s your birthright for gaining market power.

We don’t advise squeezing until it hurts for the simple reason that it’s a lot harder to sustain your company’s health without happy, prosperous suppliers. They generally aren’t going to stick around or work hard for you if they’re not rewarded for it, and so protecting supplier surplus can be just as strategic as leaving value on the table for your customers.

We have observed that too many businesses underestimate the return on delighting their suppliers. One company that doesn’t make this mistake is Zappos, the service-crazed online retailer that flamboyantly defies industry norms when it comes to suppliers. Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh is super clear about the rationale for investing in healthy supplier relationships: when your suppliers can’t thrive and make a profit, they start making choices that are bad for you, like cutting back on service and innovation. And when suppliers can thrive—as in Zappos’s case—Hsieh estimates the number of benefits as roughly “endless.”11

The company walks the talk in its supplier relationships. Zappos returns vendor calls within a few hours. Vendors who visit the company’s Las Vegas headquarters are picked up from the airport by a Zappos employee and treated like royalty when they arrive on site. They’re thrown a blowout vendor appreciation party every year at a club on the famed Vegas strip. Zappos even gives vendors access to the company’s own performance data, which helps them run their own companies better while becoming better suppliers to Zappos. And when it comes to negotiating price, Hsieh honors supplier surplus as the strategic input that it is: “Instead of pounding the vendors, we collaborate. We decide together … the amount of risk we want to sign up for, and how quickly we want the business to grow.”12

This same logic applies to all of your suppliers, including your labor suppliers. For most companies, this means your employees, a reminder that HR decisions can be as strategic as anything else we’ve discussed.c Which brings us to an essential question: What should you pay for a steady supply of good labor?

As a floor, you must pay your employees a living wage, full stop. But there’s also a powerful case for going above and beyond that minimum threshold. In her breakthrough “good jobs” research, MIT professor Zeynep Ton demonstrates the performance return on investing in decent wages and dignified jobs, even in low-cost, low-margin business models.13

She blows up the assumption that companies that compete on price don’t have the luxury of taking care of their employees. A classic Ton example is QuikTrip, an Oklahoma-based chain of convenience stores. Now an $11 billion company with more than eight hundred stores in eleven states, QuikTrip pays low-skilled employees mid-market wages, cross-trains them to perform different types of work, and empowers them to make decisions that matter in the absence of hands-on supervision.14 These investments lead to higher engagement, higher productivity, and higher retention, which then leads to lower operating costs elsewhere in the business. Ton also makes the connection from these investments to higher sales and more satisfied customers. The end result is that companies like QuikTrip are prospering because of higher labor costs, not in spite of them.

Rather than treat their employees like unreliable, interchangeable cost units, the companies Ton studies are investing unapologetically in their frontline people. They’re reducing operating costs and growing their employee surplus in the form of high wages, while fostering cultures of community and belonging in the workplace. By the way, one benefit of a great culture is that it actually pushes down employee WTS, which then grows their value surplus even more.d According to Ton, these choices generate an abundance of workforce delight that attracts and retains the best people in a talent market and unleashes them to make the business better.15 As she said to us one morning, during a walk along the Charles River (the only way we could catch her, as the entire world is excited about her work), “These aren’t just good jobs, they’re great jobs. And the firms that provide them are winning because of them.”

Ton’s research is a provocative counterpoint to assumptions embedded in many of today’s business models, including the so-called “gig economy.” The standard gig business model creates a massive amount of customer delight by meeting a basic human need (e.g., food, transportation, the trash bags you just ran out of) with lightning fast, push-button convenience, all for ludicrously low prices. Because many of these services appear undifferentiated to the market, low price has emerged as a key competitive attribute, delighting consumers even further.

The model seems to work as long as labor suppliers—contractors providing the final, consumer-facing step in the service—can capture a reasonable surplus.16 Many companies have struggled to pull this off, but an inspirational exception is TaskRabbit, the company that in many ways launched the gig economy. One of the lessons of TaskRabbit’s evolution is that even gig companies can create business models where everyone wins: customers, companies, and, yes, even suppliers.

Strategic transformation at TaskRabbit

TaskRabbit CEO Stacy Brown-Philpot (remember her from chapter 1?) made the leap from Google to TaskRabbit (initially in the COO role) when she felt a calling to do something new. She was captivated by the chance to empower an organization: “How can I help a community of people do something more than they could otherwise accomplish on their own?”17 The breakthrough business model she encountered at TaskRabbit had proven you could build a business that connected consumers to freelance workers, but there were cracks in the model that Brown-Philpot felt she could address. Almost a decade of slaying growth-related dragons at Google had prepared her for the role.

TaskRabbit was founded in 2008 to create a space where supply and demand could be met for everyday tasks. The company connected people who could do stuff—known as “taskers”—to people who needed to get stuff done. Tasks ranged from housecleaning to running errands to assembling IKEA furniture, one of the company’s most frequent requests. Customers could outsource the jobs they didn’t have time or expertise to complete, and flexibility-loving taskers could generate income on a when-they-wanted-to-work basis.

Matching taskers with jobs originally happened through an auction-like system. Clients would post jobs, and taskers would bid against each other to perform them. The model reliably generated a list of competitively priced bids for users, who then chose their tasker based largely on price and availability. In the language of strategy, the auction system had the effect of generating value for customers at the top of the value stick by shrinking the surplus of its supplier-taskers. Although magic was happening at the high end of the tasker skill spectrum, where taskers were often well compensated for their expertise, many lower-skilled taskers were being bid down in a race-to-the-bottom to offer the cheapest possible price for their labor. (See figure 5-5.)

It also took a long time for taskers to sort through jobs and find the ones they wanted—taskers spent, on average, two hours a week searching open tasks. The time and pain of dealing with the system were additional burdens, and so while user and tasker numbers were at their highest in 2013, there was some troubling news buried underneath this headline: the company’s fulfillment rate was only 50 percent. In other words, one out of two customer tasks were not finding taskers willing to do them.18

To address this problem, Brown-Philpot started at the bottom of the value stick, exploring ways to expand and protect supplier surplus. In a new platform model the company created, taskers were empowered to set their own hourly rates, which could no longer be lower than the markets’ minimum wage. Taskers also set their own schedules and made clear the kind of jobs they wanted to do. In this new model, instead of spending hours on the site trying to match their skills and interests with market demand, the company now did the bulk of that work for them.

The result was a more reliable surplus for taskers, but this also meant higher average prices for users. To make these prices palatable for the market, Brown-Philpot knew that increased fulfillment rates would go a long way. But in order to preserve—or even increase—the amount of delight customers experienced, the company also streamlined the user experience to make the customer’s hiring process faster and easier to use. The changes helped to increase customer WTP by enabling users to find a qualified tasker in a single visit to the site. (See figure 5-6.)

FIGURE 5-6

Improved TaskRabbit value stick

The new model was a wild success in London, the first place it was tested, a greenfield market where the company could avoid the pain of retraining stakeholders on a new system. User numbers in London grew three times faster than in other markets, and clients doubled the amount they spent on tasks.19 The number of repeat customers was also significantly higher, along with overall client satisfaction and user sentiment. And the all-important fulfillment rate grew to 90 percent.20

As the company rolled out the model to existing sites, Brown-Philpot overcame an initial backlash from taskers who worried about losing income. The experience taught her hard-earned lessons about managing change, including the importance of communication, particularly when suppliers’ livelihoods are on the line. It also reinforced the value of staying close to what suppliers are thinking and feeling. She created a Tasker advisory council and invites employees to both hire Taskers for their own needs and perform tasks themselves. If you order the service today, there’s a chance Brown-Philpot herself may show up.

Once she scaled the new model to all TaskRabbit markets, Brown-Philpot noticed something else surprising: instead of simply competing with each other, taskers were starting to help each other, holding classes and posting videos about how to earn more income through more specialized tasks. This created more opportunities for taskers to learn and grow (at virtually no cost to the company). Taskers were finding new meaning in their jobs by unleashing potential in each other, a leadership flywheel that was empowering people—lots of people—in Brown-Philpot’s absence.

Defy strategic gravity

This is where value-based strategy gets even more interesting. The goal of strategy is to grow the “wedges” on your product’s value stick (customer delight, firm margin, and supplier surplus) without making any of the other wedges smaller. We call them wedges because it helps people visualize the opportunity for expansion and contraction. It’s relatively easy to grow one wedge by shrinking another one. That’s what cable companies do when they raise consumer prices—and fury—without doing anything to increase our WTP.21 Great strategy asks you to work harder than that and find ways to grow everyone’s wedge.

One classic way to achieve this is by driving up your customers’ WTP, a challenge that has consumed strategists since markets were invented. Whenever you make your products better, cooler, easier to use, more fun, more convenient, and so on, you’re putting upward pressure on your customers’ WTP for them. This gives you the option to raise prices and enjoy higher margins, while also increasing how much delight your customers experience.

Additional strategies for increasing WTP include better branding and storytelling. They include finding or designing great complements (the ketchup to your hotdogs) and leveraging network effects (more users, more value). They include ideas that could fill entire books, collectively entire WTP libraries, and our objective here is not to add to this impressive catalogue. Instead, we want to remind you that strategy is an extension of who you are as a leader. As impersonal as the language of strategy sometimes sounds, with its forces and sticks and wedges, strategy embeds your humanity into the behavior of your company. It allows you to empower anyone, wherever they may be in your organization, including places you could never reach on your own.

That’s what Toyota did when it decided to cooperate with its suppliers rather than compete with them. Toyota broke from the auto industry’s norm of brutalizing OEM suppliers and committed to making them better off instead.22 The calculation was simple, clear-eyed, industrial math: more efficient suppliers would mean lower costs for Toyota. And so Toyota gave its suppliers access to the wisdom of its famed Toyota Production System (TPS). Suppliers got to learn from TPS how to lower their own operating costs, while Toyota got a progressively lower price on parts. This extraordinary learning partnership gave suppliers the chance to expand their surplus not only with Toyota, but also with every other client they served.

Again, we challenge you to bring this type of thinking to your relationships with all of your stakeholders. As you explore ways to stretch the middle of your value stick by lowering internal costs, we invite you to think particularly hard about employee compensation. This doesn’t necessarily mean bigger paychecks, although that investment may very well be in your strategic best interest (again, see Ton’s research for inspiration). Keep in mind that you may also be able to expand employee delight by giving people more flexibility, more autonomy, more opportunities to upskill and learn. You may be able to find ways to put mission and meaning at the center of the employee experience, which have been proven in countless studies to be as important to many people as the salary they’re paid.23

We offer you these anecdotal, illustrative examples—more like parables—to challenge the widespread assumption that in order for you to win as a company, someone else has to lose. We believe that you can align the interests of customers, shareholders, employees, and suppliers, particularly if you take a holistic, long-term view of your organization. In the next section, we give you the chance to test that idea end explore empowering strategies for your own organization. As you begin, get very clear on the fact that most people will be making most of their decisions without you. How will you design a strategy that will lead them in your absence? How will that strategy reflect who you are as a leader?

Find your wedge

In our experience, great strategy is creative, innovative, and above all, optimistic. Leaders who get it right refuse to accept that the gains of their customers or employees have to come at their company’s expense. They refuse to treat their suppliers as competitors scrapping it out for a fixed pie of resources. Instead, as world-class strategists, they strive to stretch the value stick and make everyone better off.

We’ve found that a simple exercise can help you spark this kind of strategic thinking in yourself and your organization. The exercise works well in both small and large groups (we’ve done it with hundreds of people at once), and it’s one answer to the perennial question of what to do at your next strategic planning offsite. For anyone who dreads that annual ritual, this one’s for you.

Sit down with your colleagues in groups of two to four people and do the following:

- Tell your company’s wedge story. Look back at the history of your organization and use the value stick framework to describe the major plot points in your strategic story. Which “wedge” formed the basis for your original strategy? How did that strategy evolve over time and which stakeholders gained and lost value along the way? Which wedge do you prioritize now? At whose expense?

- Come up with a new idea that expands at least one wedge without shrinking any of the others. The idea here is to create space for new ideas, so try to push yourselves to greenfield thinking. Dwell in the possibility of future wedges. Some questions to prompt your creativity: How could you delight your customers without increasing costs by much (if at all)? How might you help your suppliers use less time or capital in their delivery of great service to you? Could paying your employees more help you lower costs elsewhere in the business? Are there ways to make your employees’ happier without paying them more?

- Present your best idea and invite pushback. Once you have brought your best ideas and arguments to a place you like, present them to the rest of the team. Use the value stick framework to describe the trade-offs and payoffs. Which wedges are impacted? Which remain untouched? Use the feedback you receive to sharpen your thinking and make your ideas even stronger.

- Pilot at least one idea coming out of this exercise. Send a strong “How about now?” signal and reward creative thinking by executing quickly on the best one or two ideas to come out of the exercise. Frame it as a pilot and put mechanisms in place to learn quickly from the outcomes.

Use your words

True confession: we love the show Shark Tank. We love that the outsized energy and possibility of entrepreneurship—something that has brought so much color and shape to our own lives—is the animating force of the show. We love that the show’s “sharks,” investors who are pitched by contestants on early-stage companies, engage just as vigorously with the African American couple making products for curly hair as the white guy trying to build a better beer cozy. It’s a stylized, made-for-TV version of the world we want to live in, one where good ideas compete on their own merits for capital and attention, regardless of the identity of their originators. (Some advice to future Shark Tank participants: make sure you’re properly valuing the potential upside of having a shark on your team. A shark’s dollar is worth more than other dollars.)

We also love that there can be moments of pedagogical magic in an episode. Almost every concept we’ve explored in this chapter has a good Shark Tank analog. When Aaron Krause invented Scrub Daddy, a clever sponge that’s soft in warm water and hard and scrubby in cold, he found a way to spike our WTP over traditional sponges without adding much cost. When guest shark Alli Webb, founder of Drybar, reluctantly said no to an investment in CurlMix, we saw the emotions that often accompany alignment tensions. Webb appeared to love the entrepreneurs and their business model, but she was in the business of straightening hair, not making curly hair look great, which was CurlMix’s value proposition.

One part of strategy that repeatedly gets a spotlight on the show is the importance of being able to communicate strategy quickly and persuasively, in language that everyone can understand. Your plan has to be as accessible to a shark who may know little about your industry as it is to the viewers keeping up at home. If you can’t describe simply how you’re going to win as a business, there’s almost no point in showing up and getting into the tank.

We believe the same is true in the real world of leadership. To put this in starker terms, nothing we’ve discussed in this chapter matters if the rest of the people in the organization don’t understand your strategy well enough to make their own decisions based on it. As we said in the beginning, strategy guides discretionary behavior to the limit of how well you communicate it. So, let’s talk about how to communicate it.

The goal here is to understand deeply so that you can describe simply. If you understand your strategy deeply but can only describe it in a complex or jargony way, then you only get to talk to the subset of your organization that speaks that esoteric language. If you understand your strategy only superficially, then it will not survive out in the wild, in dynamic conditions where the pressure to abandon the plan is relentless. Your people will be continuously tempted to deviate from the strategy—usually for excellent reasons, like responding to a customer service request. A strategic North Star, simply described, gives us all a fighting chance at staying the course.

Pick any mode(s) of communication you want and certainly play to your strengths. Every year Jeff Bezos writes a long letter to his shareholders in which he reinforces the pillars of Amazon’s strategy. It’s addressed to investors who own a piece of the company but clearly written for every stakeholder in his orbit. Bezos is a clear, persuasive writer, and these annual letters are a great example of “deeply/simply” communication.

In his 2017 shareholder letter, Bezos reminded everyone of his internal ban on slide presentations in favor of long-form, six-page, double-sided memos that Amazon executives draft to pitch new ideas to each other. Memos are drafted collaboratively and circulated without the authors’ names, to minimize politics. Strategy meetings at Amazon start with everyone reading every word of a “six-pager” and then engaging with the ideas in what one Amazon alumnus recalled as “the most efficient and exciting meetings I had ever attended for any company.”24 When was the last time you described a meeting that way? Efficient? Exciting?

Bezos has called this practice as the smartest thing he ever did, since the discipline of crafting sentences and paragraphs forces deeper thinking.25 We tend to think of writing as a tool for influencing others, but writing is also the greatest tool for sorting out our own thoughts that human beings have invented.26 If you want to create a better strategy, we advise writing about it early and often. Start with a blank page and give yourself real time and space (think days, not hours) to develop your ideas. Share what you’ve written with your colleagues so they can help you improve your logic—and so you can start influencing their choices, even in your absence. (See the sidebar “An Ode to Old-School Strategy Communication Tools, aka ‘Books.’ ”)

An Ode to Old-School Strategy

Communication Tools, aka “Books”

One of the best strategic communicators we’ve encountered in our work is Jan Carlzon, the CEO who turned around Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) in the 1980s. In a gift to strategists everywhere, Carlzon documented the turnaround in fantastic detail in his book Moments of Truth.27 We teach excerpts of this book in the HBS classroom so that students can see what it means, on a day-to-day basis, to change behavior at the scale of a sprawling, twenty-thousand-person organization.

Carlzon has thought deeply about the role of strategic communications, particularly when it comes to empowerment leadership: “A leader communicating a strategy to thousands of decentralized decision-makers who must then apply that general strategy to specific situations must go much further. Rather than merely issuing your message, you have to be certain that every employee has truly absorbed it.”28 One way Carlzon achieved this at SAS was through a red-covered booklet he wrote titled Let’s Get in There and Fight, which the company eventually started calling “the little red book.” It was a small, illustrated, comic-style book that used few words, big type, and a cartoon airplane to explain the company’s shift to a market-oriented strategy anchored on delighting business travelers. The little red book’s storyline honored the past, articulated a change mandate, and provided an optimistic way forward, a three-part structure we have seen work again and again in turnaround situations.

According to Carlzon, he was surrounded by skeptics who thought that SAS’s highly educated, intellectual workforce would reject such a simple communication tool. In fact, the opposite happened. The book was embraced up and down the hierarchy, reinforcing Carlzon’s view that “there is no such thing as oversimplified.” Three years after the little red book’s debut, SAS came out of its nosedive, increasing revenue fivefold with an industry-leading profit margin and rapidly improving customer satisfaction, particularly among business travelers.

We’ve worked with executive teams all over the world on drafting their own versions of the little red book, and we’ve seen immediate impact in industries that range from retail to health care to energy. (One multinational firm we worked with finally broke a strategic logjam that had been in place for years after senior leaders worked through this exercise.) As you try writing your own, we suggest limiting your first draft to just three pages: The Good Ol’ Days, The Change Mandate, and The Optimistic Way Forward. Choose language and pictures that a loved one at home would understand, someone with only passing exposure to the industry. Write multiple drafts and only then layer in more pages once the story holds together.

If you question the relevance of books and pages in an age of digital communications, we’ll refer you to Marguerite Zabar Mariscal, Momofuku’s visionary, 30-something CEO. Mariscal commissioned beautifully designed, pocket-size “guidebooks” once the company reached a thousand employees. It was the scale at which she could no longer rely on direct exposure to leadership to teach people what made Momofuku’s restaurants special.29 Mariscal created a powerful new tool for leading in her absence, using the oldest trick in the book (wink).

Of course, words and pictures aren’t the only ways in which you can communicate as a leader. Your actions scream louder than anything else, and we invite you to use that bodily megaphone, well, strategically. When Herb Kelleher refused to transfer those bags, the news rocketed around every Southwest check-in counter, faster than any memo could have, reminding employees of the bag transfer policy. When Stacy Brown-Philpot quietly joins the ranks of her taskers, she’s reminding everyone in the company that TaskRabbit’s front line is essential to the success of the business.

Hiroshi Mikitani, CEO of Rakuten, transformed the Tokyo-based, e-commerce giant by embracing English as the company’s common tongue. Convinced that adopting the “business language of the world” was critical to globalizing the company, Mikitani used the full force of his CEO position to change workforce behavior at extraordinary scale, a campaign called “Englishnization” that our colleague Tsedal Neeley documented in her riveting book.30 Mikitani rolled out a system of incentives and disincentives (including demotion for linguistic resisters) that got everyone speaking English in record time. But the most impactful choice he made may have been to stop speaking Japanese himself at the office, even in one-on-one conversations with Japanese colleagues with whom he had worked for decades. Mikitani was betting the company’s future on English, and his message could not have been clearer. According to Neeley, “he was committed enough—and courageous enough—to model the change he envisioned in every single interaction.”

The emperor’s got clothes

The most effective strategic leaders we’ve observed are Mikitani-esque, internalizing their strategies so deeply that they inform their most fundamental choices. A former CEO of Vanguard once showed up in Frances’s office in a threadbare suit and shoes that had clearly been resoled multiple times. He had traveled there from the company’s headquarters through some ungodly mix of indirect flights, airport shuttles, and subway rides. Vanguard’s strategy is to be the lowest-cost player in the financial services space, which it achieves through a unique, customer-owned structure and companywide obsession with efficiency. Frances asked him very directly: “So is this just for show or are you really this frugal?” He essentially answered, “It’s both.” When you step up to the leadership challenge, whether you like it or not, there’s no option to turn off the broadcast feature on your actions. Is it who you are or just for show? The answer is always both.

We loved this exchange because it was a reminder of what a strategic leader looks like—literally, someone so committed that their strategy influences the clothes they put on in the morning. It’s also an example of using any means necessary to empower the organization to act in its strategic interest. If it takes scuffed-up shoes or speaking a new language or cartoon airplanes to get everyone to work differently, so be it. The best strategists aren’t above it.

They’re also not above changing the plan. Most strategies have an expiration date, as conditions evolve and your good intentions get roughed up by reality. The minute your competitors improve their products, that attribute map is out of date. As soon as your suppliers innovate or your customers switch up their buying criteria, the borders on your value stick become fluid again. Many companies have an annual strategic planning rite, but 365 days is a very long time to wait to adapt to changes in the behavior of your most critical stakeholders.

If you seek to lead in your absence, then get your strategy right, tell everyone about it, and revisit it early and often. And if you’re swinging for maximum absentee impact, pull that other, all-powerful organizational lever: culture. Get your culture working for you rather than against you. That’s the focus of our next chapter.

Questions for Reflection

- How do your colleagues and/or direct reports—the people you seek to lead—know what to do with their discretionary behavior? How reliant are they on being told what to do by people who manage them?

- Can you describe your organization’s strategy in simple, jargonfree language? Can the people around you?

- How do employees learn about your organization’s strategy? Can you think of new ways to reinforce that learning?

- Can you think of ways for your organization to win without customers, suppliers, or employees losing? How might you create more value for both your company and its major stakeholders?