CHAPTER 7

Look in the Mirror

What got you here will not get you there.

—Marshall Goldsmith

Brian was not expecting his agile journey to hit an inflection point, but it did in 2017.

For more than ten years, Brian Hackerson had been serving as a laboratory manager at an R&D lab for a global conglomerate making products that ranged from battery parts to automobile lubricants to home decorations. During his tenure the lab served mostly as an internal job shop. A product manager would ask him for an engineer, he would find the right skill set, log the charge code, and move on to the next request.

His office was also progressing with the times. He’d read the hot books like Lean Startup and saw a need for speed and innovation. They even took a trip to Silicon Valley and visited companies like Uber to see firsthand what modern practices look like. Given the R&D lab was inside a much larger organization, they would incorporate whatever new technique was doable within their sphere of operation. They were a stable, reliable contributor to new products.

Then 2017 happened. New leadership was installed at the CTO office and with it a new mandate: “We want you to shift from responding to R&D requests to driving innovation. Go figure out how we’re going to create value out of these modern software technologies around the cloud, mobility, big data, AI, and so on.”

Full of inspiration and support, Brian started making changes. He organized teams of three or four to work as a team figuring out what idea to deliver in a given month and start showing to people. Given the company’s culture was very socially networked, it wasn’t a complete surprise that people started talking. Word got around, more and more people got curious. Momentum was building.

A new boss and a new mandate were change enough. But then shortly after that announcement, a different set of leaders arranged for Jeff Sutherland, cocreator of the Scrum framework, to come to the corporate campus and teach a two-day workshop on product innovation. The coincidence was too much to pass up. Brian took the hint from the greater forces of fate, went to the workshop, and was summarily blown away. He describes it this way:

I was struck by his passion for what he was doing. Here’s a guy in his seventies saying, “I’m here to save the world from soul-sucking work.” And I was just like, “Yes, yes please. More of that.” I’ve been leading an R&D function for years, so these concepts weren’t foreign or brand new to me. But I came to appreciate, working with Jeff, the need for good technique and the power of purpose. So because of that, I self-selected into this role as the transformation leader and said, “There are other people that are probably far more qualified on paper, but I know this organization, I know the company. I can make this happen.” And so I went after it.1

What had been a set of informal experiments was now a formal role, and it began to snowball. More and more people were coming to visit the lab, ask questions, and request help. Fast-forward a year into the journey, and the total number of visitors hit a thousand.

This was getting big. Fast.

Eventually, the pressure started mounting. Brian began to feel burnout and to wonder about his own performance as a leader: What if I don’t have all the answers? What if I can’t get to everyone who wants help? What if we start making mistakes? It soon became overwhelming.

In reality, he was doing just fine. But his own self-perception of his performance was becoming an issue.

What happened is actually more fundamental. It was what was going on between my own ears. The imposter had moved in, taken up residence, and was running not just my day job but running my life.

The transformation had hit an unexpected, personal roadblock.

The Problem with Leadership

As discussed earlier in this book, a key aspect of fostering organizational agility is the evolution of the organization’s cultural mindset. Therefore, as a change leaders we tend to be externally focused on shepherding the mindset change in the people around us: senior leaders, peers, teams. But there’s one person whose growth we tend to forget about: ourselves.

In case you haven’t noticed, the underlying thread so far in this book is you. Whether you are like Brian and initiated your role of agile leader, or you were ordered to take the task of creating agility in the organization, you are the originator of the next phase. As the champion for improving the way we work, you are the fulcrum, you are the force multiplier.

You are the agile leader.

Serving this role will ask much of you. It will require

… more of your effort than you think,

… more depth than you already have, and therefore

… more personal change than you could ever anticipate.

In Brian’s story, he had been on a gradual and steady move toward modern practices. He already had an agile mindset. But when it came to emulating, broadcasting, and reproducing that mindset at a larger scale, he simply was not fully prepared for the ride.

For other leaders, the struggle is the other way around: you see what needs to happen, but your staff, your peers, your leadership team simply aren’t changing as meaningfully or as quickly as needed. You feel dragged down by the very organization you are trying to change, and it’s just exhausting.

The personal leadership journey for any agile champion is almost always the most forgotten element of the transformation and simultaneously the most important.

Here’s how the transformation happens on a personal level:

• The Boost. Yes, it was good to mobilize them toward real change.

• The Barrier. And yet, the pace and degree of change feel wrong.

• The Rebound. So now, look in the mirror.

The Pattern of Untapped Leadership

The Boost: Yes, It Was Good to Mobilize Them Toward Real Change

You introduced new techniques. People are experimenting. New conversations are happening. Both resistance and results are emerging.

Leaders Mobilize Their People

The Barrier: And Yet, the Pace and Degree of Change Feel Wrong

People are doing it wrong. Skeptics are fighting back. Too many are reverting to old habits. Others are taking credit and taking control. Everyone is pulling in all directions. This is not what you bargained for.

Leaders Struggle with the Change They Created

The Rebound: So Now, Look in the Mirror

Can you tolerate agile mistakes? Can you accept leadership expectations different from yours? You forgot about changing yourself.

In order to scale the leadership capacity of the organization, we have to start with the key role model for those behaviors. We have to start with you.

In this chapter, we will explore the ways in which an agile journey will put your personal leadership to the ultimate test:

• The leadership gap. We will explore the unique expectations placed upon leaders in today’s context, and the very real pattern that most leaders do not live up to those expectations.

• Defining effective leadership. Research has proven the specific leadership competencies required to thrive in such environments.

• Close the gap. Finally, we will talk about two key practices shown to build leadership capacities to achieve higher levels of impact: consistent reflection and intentional feedback.

Agile organizations are only created by those leaders who exhibit personal agility. If you’re curious about what the next level looks like, then let’s explore exactly what that means.

The Leadership Gap

Over and over, we hear about the problem with senior leadership. In our survey research, we see a recurring barrier to organizational agility:2

“Inadequate management support and sponsorship”

“Lack of agile executive leadership”

“Lack of support from executive leadership”

“No sponsorship/support from senior management”

The temptation is to think that this refers exclusively to executives. Certainly that is important. Change management research confirms the greatest indicator of successful change is “visible and active sponsorship.” However, that same body of research also asserts that our people want to hear how their specific job is impacted “from their direct supervisor.”3 That means our teams need clear engagement from the top-level leader to the lowest-level leader, and therefore everyone in between.

If you are an influencer, then you are the leader they are looking to. Also, if you are leading an organization into a new way of working, then by definition, others are following behind you. You are farther in your journey than most of the people you are mobilizing. They need you to scale your leadership capacity, so that you are able to

• Tolerate those who are slow to adopt

• Show empathy to those who resist and complain

• Explain the changes and the reasons for them

• Frame the changes in the context of where your teams have been before

• Adjust your talking points, depending on your audience

In their book Scaling Leadership, Robert Anderson and William Adams, the creators of the Leadership Circle, describe this tension as a gap between the leadership you are capable of and the leadership that is needed of you. Specifically, “The complexity of my heart and mind, my internal operating system, is not enough for the complexity of the context we face.”4

Most of us have learned our leadership roles in a different context. We’re used to the stability, certain simplicity, and clarity of what we know. We’re used to this. But the world is moving into a more challenging reality, often referred to as a VUCA world. VUCA is a term coined by Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus in the 1980s, and popularized by the U.S. military over the last several years. It describes the nature of today’s world that makes leadership so hard:

• Volatility is unexpected change, causing disruption. What was true yesterday is no longer true, throwing everything into disarray.

• Uncertainty is unknown change expected in advance, causing anxiety. This is knowing that whichever road you take could be the wrong one.

• Complexity is unexpected scale and interdependency, causing overwhelmedness. As soon as you’re confident of a path forward, more information comes to light.

• Ambiguity is about unwanted ownership, causing frustration. With so much happening so fast, we have to move forward with imperfect information. This forces our people to make more detailed assumptions than they are unaccustomed to making.

And so many of us—whether we’re a team lead, middle manager, or executive—we’re still expecting stability, certainty, simplicity, and clarity. But we’ve watched the world change right in front of us, and everyone in our teams, departments, and organizations are looking to us for how to move forward. That’s the leadership gap. Put another way, an organization’s agility cannot exceed the agility of its leaders. Your leadership skills and tool kit are being stretched like never before. You need to fill this gap.

Defining Effective Leadership

Since the dawn of mankind, the debate has raged over what constitutes good leadership. From generals to monarchs to priests, humanity has assessed leadership prowess against a smorgasbord of characteristics. Even through the industrial era and into the twentieth century, good leaders were said to be more extroverted, more charismatic, more masculine, more intelligent, and just better overall human beings. This culminated in the Great Man theory, popularized by Thomas Carlyle in the mid-nineteenth century, who concluded “The history of the world is but the biography of great men.”5

In other words, the beginnings of modern management included the notion that effective leaders are supposedly born and not made. The bad news is this mindset carried on from generation to generation, in every field of leadership. The good news is that simply does not match with science. We now live in a world that benefits from the very real research into what leadership means, what works and what does not work, who can and who cannot thrive.

Let’s take a look.

Effective Leadership Is Flexible, Not Fixed

Without question, the most popular leadership model over the last several decades is situational leadership.6 Its key point is that as followers journey through varying degrees of competence and confidence, the leader should apply an appropriate amount of support or direction. Effective leadership, therefore, is not about the most powerful innate style, but about the most appropriate style.

There is a sort of common sense to the concept: be the leader a given person needs you to be. As a supporting point, all of us have been unimpressed by that grumpy supervisor who would declare, “My leadership style is my style. If people can’t handle it, that’s on them.” Unfortunately, those grumpy supervisors are butting up against a leadership principle that has been formalized over the better part of a century:

• Published in 1975, the Path-Goal Theory asserts that a specific leadership style is only effective based on the employee’s goals and the nature of the work at hand.7

• From 1967, the Fielder contingency model states that a leader’s effectiveness is based on two variables: leadership style and situational favorableness.8

• Starting in 1939, the Harwood studies by Kurt Lewin were the first to formulate distinct leadership styles, and found that each had a different kind of impact on the culture of a study group.9 These studies became the foundation of the field of organizational development.

The most popular validation of the idea of context-driven leadership came in a landmark article in 2000 by the sometimes controversial author of Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman. The article published a study measuring the correlative impact between specific leadership style and organizational impact. The conclusion?

The best leaders don’t know just one style of leadership— they’re skilled at several, and have the flexibility to switch between styles as the circumstances dictate.10

As champions of modern ways of working, this means your people need you to exhibit personal agility. Not merely to role model the adaptiveness to change we’re promoting but also to have the patience, empathy, and humility to guide them in their walk.

Effective Leadership Is Balanced, Not Biased

Many debates over effective influence center around whether leaders should focus on people skills or achievement skills— whether it is relationships that drive results or action. The science tell us sustainable impact requires both.

Let’s go back to Anderson and Adams. Their research has yielded what they describe as the Universal Model for Leadership,11 and rests on a body of over 1 million data points. The data reveals that effective leadership correlates to effectively wielding both the people side and the task side of the proverbial coin.

The People Side of Leadership

On the one side, effective leaders create new possibilities through relational competencies like caring connection, collaborator, composure, among others. In contrast to the Great Man theory, the research shows that these competencies are only effective when performed with purpose and intent. Moreover, these skills improve with practice over time.

By contrast, when those relational skills are overrun by impulse and instinct, they turn into counterproductive reactions like pleasing, passive, and distant. Put another way, when a leader is too focused on the people side, it can negatively impact results and thus effectiveness.

The Task Side of Leadership

On the other side of the leadership conversation are task-oriented competencies like sustainable productivity, systems thinking, or purpose and vision. Similarly, when these skills are over-applied or done merely on reactive instinct, they too have a darker side that cloud the leader as perfectionist, autocratic, and arrogant.

Bill Joiner, a Boston area researcher, has been collecting his own data on leaders worldwide. His findings point to a progression of sequential stages of increasing leadership skill. One compelling discovery is how power is displayed at each increasing skill level.12

At the most common skill level (45 percent of all managers), leaders are overly assertive with subordinates and overly accommodative to their supervisor. These are two distinct power styles that exist in every leader. But at lower skill levels, they show up at distinctly different scenarios, based mostly on instinct and reaction. However, as leaders grow, increasing their depth and capacity, Joiner noticed an increasing blend of these two power stances: more listening to our people and speaking truth more often to those in higher positions. The highest levels of leadership performance show a near seamless interweaving of these seemingly opposite dynamics. Accommodative people skills, assertive task skills—the science tells us effective leadership requires both.

Close the Gap

Now we know the kind of leadership skills we are supposed to develop. But how do we go about that development? The research reveals two practices that correlate to higher levels of leadership skills:

• Consistent reflection

• Intentional feedback

The Practice of Consistent Reflection

Shortly before our Minnesota lab manager Brian’s world was disrupted at work, he had bumped into Dr. Michael Gervais, host of the Finding Mastery podcast.13 Brian credits Gervais as the one who helped him get curious about mindfulness practice as a form of brain training. Gervais explained it’s not the religious cult thing that skeptics are concerned about. Rather, the science of neuroplasticity and high-performance psychology asserts that we can reprogram our brains to new ways of thinking. We are not hardwired to be the same people we were at birth. You can change; you can develop.

So Brian tried it out. Through a certain amount of practice, he says, “I became aware of the imposter in my head: ‘When is my boss going to fire me? Why would these people even listen to anything I have to say?’ On and on and on. I knew it was there, but I chose to listen to it anyway.”

He kept with it and eventually had an aha moment: “There was an inflection point where I pulled out of the pit of despair. I was able to say to myself, ‘Wait a second. Okay, this self-doubt is really stupid. I see where we need to go. I see a path to get there. And you know what? I’m not going to get it perfect, but I got this.’ That moment of self-care prompted even more energy. Color came back into my life.”

If strong leadership is about applying the right balance at the right time, then it requires the perspective to do just that. The perspective to zoom out from your current situation, see yourself in a larger context, and then zoom back in to deploy the skill that best fits that context. This is the essence of building a reflective capacity, a core skill that correlates to measurably higher leadership effectiveness.

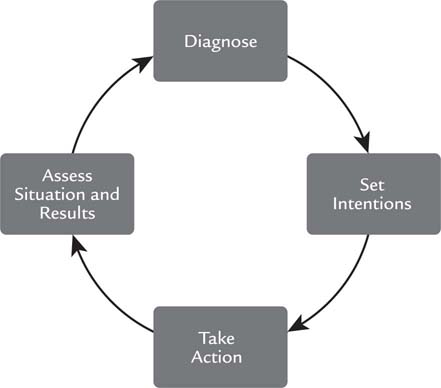

Joiner describes this capacity as a cycle of four actions:

1. Assess situation and results. Scan your environment and determine what issues (problems or opportunities) need your attention.

2. Diagnose. Once you have an issue in mind, think through the underlying cause or barrier.

3. Set intentions. Ask yourself, “What do you want?” and think through a pathway to get there.

4. Take action. Act with intent toward your goal.

Move back to step 1, examine the results of your actions, and continue the cycle.

Joiner makes the point that everyone moves through this cycle regularly, but we do so unconsciously. Most of our daily decisions and actions are based out of instinct, habit, or autopilot.

This was the secret to Brian’s breakthrough. He was iteratively listening to the narrative in his head, trying an action, and then testing that narrative against reality. Listen, try, test. Over and over until he could see the bigger picture.

Options for Practice

By now you might be thinking, “That sounds great, but how do I do it?” While meditation works for some, many of us just don’t resonate with it. So let’s turn to some successful CEOs for other ideas:

Just Pause

In one of the Finding Mastery episodes, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella explains his own version of meditation each morning.14 He wakes, sits up, puts his feet down, and pauses for ninety seconds. “It grounds you,” he says. “It gets you in touch with yourself and the world around you. It’s fascinating.” No chants, no incense, no yoga. Just pause.

Exercise

Engaging in physical activity allows the brain to relax. Virgin Group founder Richard Branson starts every day with exercise. He prefers tennis, cycling, or kite surfing, because, he says, “Exercise puts me in a great mind frame to get down to business, and also helps me to get the rest I need each night. There’s nothing more satisfying than knowing I have applied myself both physically and mentally every day.”15

Soak

Buffer CEO Joel Gascoigne adds a little bonus to his morning exercise. “Most days I do 30 minutes of cardio (swimming or running) and then 10 minutes in the hot tub. Then I have a simple breakfast, before starting work. This gives me the best start I’ve found for my day, gets the endorphins going, and makes me feel refreshed and ready to make progress.”16

Wake Up Early

By now you’re wondering, where do these people find the time? Well, they get it in the mornings. Twitter’s Jack Dorsey wakes up at 5 a.m. For Apple’s Tim Cook, it’s 3:45 a.m. Successful people don’t sleep in.17

Journaling

Another option is to be your own coach, using your own language. The kinesthetic act of reading and writing can engage our fuller minds. The leadership mega-blogger Michael Hyatt has described journaling as a practice he has seen with almost all the high-powered leaders he’s met. Curiously, his blog has served as a very public journal of his thoughts, making him a powerful example of how simple it can be to use the written word as a reflective tool.18

Retreats and Sabbaticals

The best way to sift out truth from noise is to get as far from the noise as possible. During his Microsoft days, Bill Gates would famously take a week off in the woods twice a year. He would spend almost all that time going through books and papers. “I would literally take boxes out to a beach place and sit there for a week reading them day and night and scribbling on them to put it entirely online.”19 Both academics and clergy have an established tradition to leave their day jobs for months on end, with the intent of rethinking the biggest questions of the universe. For you, it might be enough to take a weekend to yourself and see what percolates to the top of your mind, without the daily grind.

Executive Coaching

Bill Campbell was the “trillion dollar coach,” according to the book of the same name.20 This name was given to him by his clients—Steve Jobs, Eric Schmidt, Warren Buffett, among others. They all asserted that Campbell was a key reason for their successes at generating a collective trillion dollars of economic impact. Why did they speak so highly of him? One key theme was the tough questions he would ask CEOs, forcing them to check their assumptions and think more deeply about situations and choices. If it worked for them, coaching can help you too.

Here are some examples of how Emmit is working on building his reflective habits after receiving executive coaching.

• “During my morning run last week, it occurred to me which vendor partnerships are worth bringing along on this transformation, and which I could live without.”

• “Last month’s journal entry shows me more bothered by the Q1 metrics than I am now. I wonder why my feelings have changed.”

• “In our last coaching session, we talked about my desire to get more connected to my staff, and I still believe that’s important. But with my schedule so much in demand, I guess I’m struggling with whom to disappoint in order to make that happen.”

• “I took the weekend to go hiking without my family. It helped remind me what legacy I want in my career. I feel more grounded against the inevitable bickering that awaits me at the office.”

You have several options for activating your mind. Pick the ones that work for you, and start building the critical skill of reflective capacity.

The Practice of Intentional Feedback

Let’s go back to Brian at the R&D lab. He was making progress on becoming the agile leader he wanted to become. But to go farther, he knew he needed an outside perspective. In 2018, the Global Scrum Gathering came to his home town of Minneapolis-St. Paul, bringing thousands of other agile champions with it. He decided to go check it out, see what others might have to say.

It was there he bumped into Michaele Gardner, an agile coach and adjunct instructor at the University of St. Thomas. They started a conversation about their respective experiences, what it means to them, and what it means to those they serve. Their contrasting perspectives were refreshing: he was the data, numbers, and math guy; she was the technologist with roots in psychology and counseling. That collaboration continued weeks after the conference through a series of conference calls, coaching each other in various challenges.

Then another inflection point happened. Brian describes it this way:

One day, I was sitting in my basement and we were on a teleconference, staring at a page on a shared screen. We were talking through the twelve principles of the Agile Manifesto and how they relate to leaders in an agile context. At one point during that conversation, I said, “What if we changed them? What if we rewrote the first principle so it said, ‘Our highest priority is to be our best self so that we can help others be their best’?”

So, they did. Together they rewrote every single one of them, and something clicked. It was a rewarding experience to have their thinking challenged and reframed by a like-minded professional. But it didn’t end there. Michaele was at another conference when she briefly met Kent Beck, a coauthor of those original agile principles. Kent helped push the conversation to the extreme— he brought it beyond “self care” and to “best self” outcomes. More feedback.

They posted their new principles online at agilebestself.com, which invited comments and encouragement from their colleagues. Still more feedback. They went a step further and delivered these principles to seventy of their peers at a local Twin Cities agile meet-up. Brian was dumbfounded at the positive response: “They showed up in the evening to come to this. That number of people was shocking to me. On a Tuesday night ? Who would do this? And so we delivered the workshop and when we got done, they all stood up and cheered.”

All that happened because Brian took the intentional effort of going to that conference seeking professional feedback. He was discontent with his assumptions and perspectives, and needed an outside party to inject new information into his understanding of the world.

It turns out that deliberate practice of intentional feedback is a secret superpower for agile leaders. Let’s go see what that is.

The Missing Feedback Loop

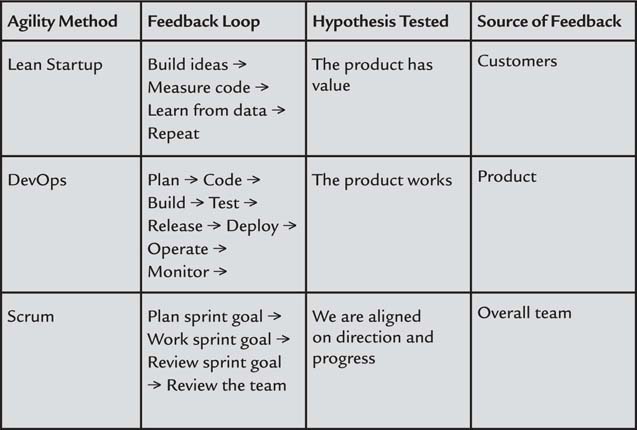

One of the fundamental ingredients of all agility is feedback. Virtually every one of the formal methods is designed to test some kind of hypothesis, evaluate the results of that test, and use the learning to inform the next steps.

• The Lean Startup loop. Ideas we build → code we measure → from data we learn → which impacts the ideas, restarting the loop. We engage the customer and the market to test the hypothesis that people actually want our stuff.

• The DevOps loop. Plan → code → build → test → release → deploy → operate → monitor → which impacts the plan, restarting the loop. We design the system to test the hypothesis that things actually work.

• The Scrum loop. Plan sprint goal → work the goal → review the goal → review the team’s effectiveness → which informs the next goal. We schedule conversations to test the hypothesis that we are aligned on where we are versus where we should be.

Do you see what’s missing from these feedback loops?

You are. The agility leader.

Comparison of Agile Feedback Loops

Certainly, many of the methods target skills growth for the on-the-ground product teams. Techniques like pairing people together and team retrospectives are sometimes used to offer feedback to individual contributors, to help them grow on a personal professional level.

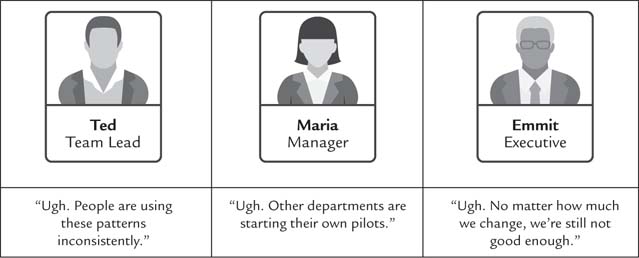

But what about the founder? The product owner? The transformation leader? The Scrum Master? What about Ted, Maria, or Emmit?

In all the push for iterating and improving everything we do, we have no formal mechanism for iterating and improving the leadership skills of those driving agility. We talk endlessly about the need for “servant leaders” to develop a “growth mindset” that “empowers the team.” But we forgot to apply the same formalized feedback mechanisms to achieve that leadership goal.

“Okay, Jesse. Fair enough. But how do we do that?” Glad you asked.

Spinning Around in 360

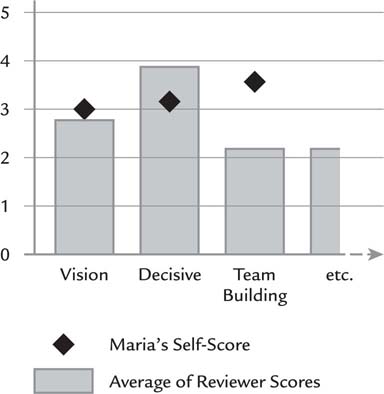

One option to generate personalized feedback on how you’re doing is to use the established technique of a 360 leadership survey. Here’s how it works.

The survey asks some questions about how you approach your leadership work. Then those same questions are posed to your supervisors, mentors, peers, colleagues, and subordinates. Usually, the responses are anonymized to encourage candor and then aggregated into a team average. This allows for a contrast between how you perceive your performance versus how others perceive you.

Maria’s Leadership 360 Review

There are an uncountable number of 360 tools to choose from. You can choose from instruments created by the aforementioned Anderson and Adams or Joiner, or your company may have one that was developed in-house. Regardless of which you use, the intent is the same: to get feedback on how you are perceived as a leader. The chart shows what a snapshot of the results for Maria might look like.

A quick glance at the chart reveals a few conspicuous trends:

• Self-awareness. In the area of “vision,” Maria’s self-score is very close to those of the reviewers. Seeing yourself the way your colleagues do can be an asset in challenging situations, so that you don’t overplay or underplay your role. Here, she agrees with her peers that she is only average at crafting and communicating vision, which can serve as an area of shared understanding.

• Hidden strengths. In the area of decisiveness, Maria scores herself lower than her reviewers do. This could mean her team is grateful for her decisions, or it could mean she has a simmering lack of confidence in the decisions she does make. The tool doesn’t tell us why there is a gap, only that a conversation could open up more possibilities for her.

• Blind spots. Maria’s self-perception on team building is much higher than that of the reviewers in the area of team building. This might be because the team has recently grown and she’s been too busy to create some collaborative glue between the older and newer team members. Or it could be she doesn’t know where to begin with that mushy stuff. The data doesn’t tell us the cause; it only tells us a conversation should happen here.

In addition to the quantitative scores, all good feedback instruments include qualitative comments. It’s in the comments where the numbers start to show their true meaning to Maria:

“Maria has been stretched by the team’s recent growth. She should consider delegating more or asking for help.”

“We do a lot of work, so I’m grateful for Maria’s decisiveness. That said, I do wish she would explain the big picture more often, so we know how she comes to those decisions.”

“Maria is pretty vocal about focusing her team on execution and staying out of our strategy debates. But given her team’s been making improvements in the organization, I think she’s missing a key influence opportunity. I would like to see her flex more visionary skills.”

As you can see, this kind of instrument can be powerfully insightful. But sometimes it can go in a negative direction. People can be unusually harsh in anonymous surveys. Below are some tips for approaching technology-driven feedback with success.

• Discuss context, not truth. One concern around 360s is that they are deeply contextual. If an adrenaline junkie scores Maria as 3 out of 5 on “quick decision making,” that doesn’t mean she’s average at it. It only means that’s how that one person sees her. And that is the point. Leadership perceived is leadership achieved. How people experience you may not be the fullest truth of who you are. That said, the perception of your leadership is how people are experiencing you, and knowing that is the first step to improving your impact.

• Seek development, not assessment. Whenever we use data to measure ourselves, it can be tempting to place a value judgment on whatever the numbers end up being. However, looking for high scores, or at least scores higher than others, can be a recipe for dysfunction. Academics, researchers, consultants, and seasoned leaders disagree on much, but they all agree on one thing: the point of 360s is not where you are, but rather what your next step is.

• Choose your raters wisely. One thing the Internet has taught us is that people can be really mean, especially when technology keeps us incognito. Using a tool to collect anonymous feedback can yield some false negatives, both in the qualitative numbers and the qualitative comments. Avoid that mess by choosing only those people whose perspective you trust and respect. Then give them a heads-up as to why you’re asking them and what your goals are.

• Use a coach. Sometimes the feedback we get can be confusing or even crushing. Use a professional coach who can walk you through the results. A neutral perspective will help you sift away the distracting parts and get to the true substance that matters to you.

• Chart a path forward. The whole point of feedback is to adjust your path. As you go through your results with your coach, design a roadmap for building on your key growth area. Then schedule recurring check-ins with your coach or a few trusted colleagues. That way you can get sustained accountability on progress toward your goals.

Just Ask

If using a formal feedback instrument sounds like more hassle than it’s worth, don’t worry. You don’t have to. You can use the old-fashioned approach to get feedback: go talk to people. Whether it’s your boss, your peers, or your teams, you could get some very powerful insights by asking pointed questions. For team lead Ted, it could look like this:

• “How am I doing with walking the agile talk?”

• “Is the reason behind these practices clear to you? To others?”

• “Do I give enough ‘space’ for people to contribute?”

• “Does the team feel like I stick up for them?”

• “What does support from me look like?”

I know. These are tough questions. Potentially dangerous questions. How do we keep the conversation from getting weird? How can we make sure we get good, actionable information? To try this more informal feedback approach, leadership author Peter Bregman offers some very helpful tips:21

• Be clear that you want honest feedback. Let people know they’re doing you a favor by being truthful. “Don’t be nice,” you can tell them. “Be helpful.”

• Focus on the future. Avoid the drama, frustration, and guilt of the past. Instead, ask them to offer recommendations for being more effective going forward.

• Probe more deeply. Don’t let them off the hook. If you sense there’s something under the surface of a particular comment, ask, “And what else?” or “Tell me more about that.” If you’re not getting anything of substance, try being more specific: “How could I get more active participation from you in big-room planning?”

• Listen without judgment. This is the hardest part. If they offer something critical, it may well be a test to see if you’re serious about hearing the truth. Try your best to redirect your natural feelings of defensiveness, injustice, or frustration. Remember, you asked for this awkwardness because you have a much bigger goal in mind. Whatever input you receive, express your gratitude for their honesty.

• Write down what they say. I love this suggestion for two reasons. First, it shows you’re paying attention and respecting the input you receive. Second, it serves as an emotion safety net, giving you something to focus on when you hear something annoying. Simply write it down, be polite, and trust the process.

Remember, learning is the secret sauce to higher performance. Feedback is the means to achieve deep learning. Pursue it ruthlessly, regardless of whether you use a fancy psychometric instrument like a 360 survey or you start engaging people in honest dialogue.

An Agile Leadership Development Plan

Reflection and feedback. These are two development actions that can and should be pursued to expand your capacity as a leader and an agile practitioner. But don’t limit yourself to just one action at one point in time. Growth is continuous and layered, so you want your own actions to be continuous and layered. Much the way DevOps, Lean Startup, and Scrum give us overlapping feedback loops of varying cadences, a personal development plan should feature the same.

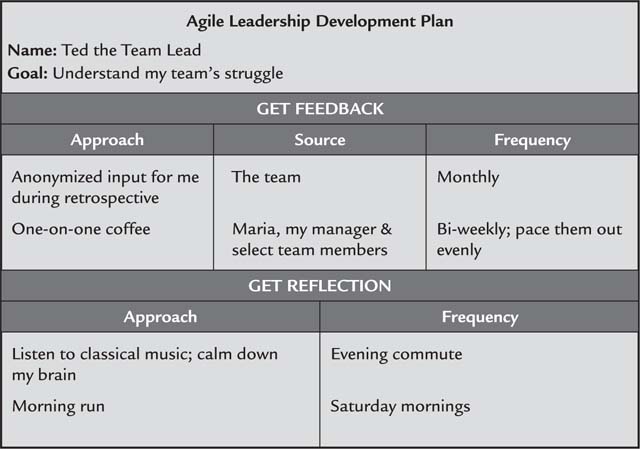

On the website for this book is a template for designing such a plan. It is a simple worksheet to help you think through both sides of the equation.22 Here is an example of how team leader Ted could use the worksheet to sketch a path forward.

“My biggest hurdle right now is the team’s struggle with new technical practices. I guess the best source of feedback is the team itself. I could leverage our regular retrospectives, while also trying the occasional informal coffee chat. Regarding reflection, I’m not able to take much out of my day for, so perhaps if I leverage those chunks of time I already use—aha! What if I turned off the podcasts during my commute and just let my brain wander? That might be interesting. Also, I’m pretty reliable with my Saturday morning run, which could be used as some reflection time.”

When Ted has finished scribbling on the worksheet, it looks like the figure.

Summary

In this chapter, we have done the hard work of looking in the mirror. Sometimes changes are happening, but the pace and degree feel wrong. We’ve learned about:

• The leadership gap. The expectation of agile leadership is to guide an organization through more volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) than we ourselves can tolerate.

• Defining effective leadership. Research over the last century has shown us that navigating that VUCA requires a leadership style that is flexible from situation to situation, and balanced across the task-side and the people-side of daily work.

• Closing the gap. Rather than try to grow every leadership skill, we make the most progress focusing on the practices of continuous reflection and intentional feedback.

Your growth is critical to your team’s growth. Too often the agile conversation is about making “them” more innovative, collaborative, and responsive. Too often we forget about our own personal agile journey. As a result, the surveys identify over and over a key roadblock is “inadequate leadership support.”

Unless you embark on your own journey, you will only get so much out of the teams on their journey. The good news is we now have a way forward