CHAPTER 8

Own the Narrative

Stories constitute the single most powerful weapon in a leader’s arsenal.

—Dr. Howard Gardner, professor, Harvard University

It was my job to lie about Agile.

At least, that’s how it felt.

The CIO at a large bank was the proud sponsor of new credit card technology that enjoyed a very successful regional pilot. Now his vision was to scale the success of that technology across the entire North American region, with the help of a big-brand brick-and-mortar retailer. The bank would upgrade the technology, and the retailer would deploy it to hundreds of locations across the United States. Both sides were salivating at an opportunity that was valued at $2 billion.

But it was a complex undertaking. Success required supporting every variation of state tax laws, adding support for Spanish speakers, integrating with the loyalty program, scaling the back office card operations, and moving the technology to a place that could handle the increased load. The good news was that the organizational cultures of both sides were steeped in analytical prowess. They were committed to getting it right, because the stakes were just too high. But the market pressure was also high. The retailer made it clear we needed to be done in twelve months. The estimated time required? Twenty-four months.

How do you overcome high risk and high complexity, and do so on such an aggressive timeline? The CIO had a plan: “Step 1, let’s hire hundreds of people right away. Step 2, let’s make them use agile methods. To get it right, and to get it fast, I want 80 percent of the entire backlog identified in the next three months. Once that backlog is approved by the retailer, then we can get started.”

So they hired me to coach up the agility needed to get it all done. When I showed up to the office and heard this story, it took me a moment to digest what I’d just heard. Namely, we were instructed to:

• Plan everything before we do anything.

• Then do it in a fraction of the time required.

• But everything is planned perfectly, so there won’t be any mistakes.

• It was my job to coach everyone to make this happen.

This was the exact opposite of the flexible, incremental, experimental approaches associated with the lean/digital/innovation mindset. Yet somehow, a small army of technology professionals were supposed to figure this all out.

So they came. Scrum Masters, project managers, program managers, analysts, technical writers, and testers began arriving en masse to our glass-enclosed office building in downtown Wilmington, Delaware. All eager to accomplish big things. They all looked at me expectantly. What imaginary management magic would we use to do the impossible? How is this anything like the agility we’ve seen in the wild? How is this not a violation of everything we stand for as modern innovators?

It was my job to advocate for an ill-conceived, confused, and inevitably doomed version of agility. It was my job to tell a story that was both impossible and unbelievable. They hired me for this, and it was my job to own it.

The Problem with Perception

As the agile leader, you have a different perception of reality than those you lead. The fact that you are driving change means you are moving people into a new reality they cannot yet see. They do not see the positive momentum that has been made; they only see the pain and frustration injected into their lives. Even more annoying, they don’t yet have the mindset to see mistakes, pain, and awkwardness as necessary steps for growth. So the greatest value you can add right now is to help them make sense of it all.

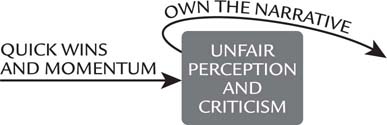

• The Boost. Yes, it was good to score quick wins and spark momentum.

• The Barrier. And yet, the misperceptions and criticisms are mounting.

• The Rebound. So now, own the narrative.

The Pattern of Untapped Support

The Boost: Yes, It Was Good to Score Quick Wins and Spark Momentum

In the previous chapters, we’ve seen all the boosts available to get transformation started. You leveraged your role, installed best practices, ran several local pilots. You invested in a new culture. You captured several opportunities. You mobilized several teams. These were all quick wins to generate momentum that simply did not exist before.

The Barrier: And Yet, the Misperceptions and Criticisms Are Mounting

Despite all the progress made, people are fixated on those barriers we’ve discussed: People are frustrated that the progress isn’t what they wanted it to be and are quick to criticize the changes made. Several of the vocal influencers aren’t on board, the pilot teams’ practices are poor, their results are limited. The culture isn’t moving. There’s too much going on, and they’re challenging your leadership. Given everything that’s been done, it’s an ocean of negativity that simply doesn’t make sense.

Perhaps your peers had a vision based on unrealistic outcomes. Perhaps they feel threatened by the changes to their role. Perhaps your pragmatism doesn’t match the dogma they expected. Whatever the reason, you’re facing a rising resistance.

The Rebound: So Now, Own the Narrative

The reason why the negativity is taking hold is because it contains a grain of truth. How do we take control of the story by acknowledging that truth and framing it as progress? We do that with an attitude and a technique:

• Half empty, half full. Sometimes complaints stem from logical consequences. Sometimes they are simply the result of a pessimistic attitude. We learn that both war veterans and improv theater performers know the difference between pessimism and pragmatism. That difference sets the stage for our talking points about change.

• Framing the change narrative. We borrow a storytelling template from fiction writing and import it into the leadership context.

• Responding to common criticisms. With these two concepts in hand, we will then be able to systematically deconstruct those recurring complaints.

We hear that storytelling is a key leadership skill, but nobody explains how to do it well. In this chapter, you will learn several tips and techniques for doing exactly that, and thereby enable the next level of transformation.

Half Empty, Half Full

The cliché is a cliché for a reason. It is an obvious recurring fact that different people view the same situation as good or bad. It’s optimism or pessimism.

On the one hand, your agile journey has been mired with grumbling, compromise, and mistakes.

On the other hand, you have much to brag about. People are exposed to new ideas, which were previously totally foreign concepts. Teams are talking more to each other than they were before. We’ve forced dialogue about our traditions, and why we should change some of them. The deeper reality is that both perspectives are simultaneously real reflections of reality. Both are true.

The Stockdale Paradox

In his classic business book Good to Great, Jim Collins introduces what he calls the Stockdale Paradox, named after U.S. military veteran and former vice presidential candidate James Stockdale.1 He was held as a prisoner of war in Vietnam for several years, starved and tortured with no reason to believe he’d make it out alive. Yet he survived. His strategy? He was able to overcome his adversity by building an attitude of simultaneous optimism and pragmatism.

Leadership as Half-Empty versus Half-Full

In the book, Stockdale explained the mindset this way: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

Stockdale was able to avoid the temptation to give up and do so despite acknowledging the truth of his situation. He goes on to explain the dangers of not doing so:

“Who didn’t make it out? Oh, that’s easy,” he said. “The optimists. They were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

We need that Stockdale mindset, where we can acknowledge our struggles and keep hope for future possibilities. Before we learn how that gritty mindset applies to the business of change, let’s take a quick detour to improv theater.

Yes, And

I’ve been through some improv theater and can personally vouch for what most people already know: it is a lot of fun. It’s fun not just for the audience but for the performers as well. Coming up with creative responses to awkward situations creates great positive energy and, of course, often leads to some good laughs.

Curiously, it’s not based solely on the individual talent of the participants; it’s based on the philosophy called “Yes, And.”2 Even more curious, the secret of improv theater relates directly to Stockdale’s philosophy on surviving a prison camp.

• We verbalize “Yes!” Improv performers acknowledge and embrace what your stage partner just said or did, no matter what. If they said a swear word, invented a new character, went off the storyline, danced a little jig, or anything else, we accept it as-is. No objecting to the unexpected turn of events. No complaining. No critiquing. It just is. This relates to the pragmatist part of the Stockdale mindset.

• We verbalize “And!” Next is offering something to the situation that moves the scene forward. Rather than halting movement with an objection or critique, we inject something additive. This relates to the optimist Stockdale, who did not accept his tragic conditions.

In the previous chapters, we’ve covered the Untapped Agility pattern for six common issues. However, our critics don’t see the virtues of the progress made; they only see the pain points. So we need to inject a generative, additive, corrective attitude into the story. Specifically, we can use the phrase “Yes, And” not just as a conceptual guide but also as a template to articulate the Stockdale Paradox for each of those challenges:

• For criticism over buy-in. “Yes, I recognize that not everyone is on board with the change. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation of what agility is about. Therefore, I believe we can now align on what parts relate to us and why.”

• For criticism over impact. “Yes, I recognize that agility so far is localized. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation for others to follow. Therefore, I believe we can now give it away to other champions.”

• For criticism over practices. “Yes, I recognize that our practices are immature. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation to evolve from. Therefore, I believe we are now able to set the textbook aside and evolve into our own agility.”

• For criticism over workload. “Yes, I recognize that we are always behind. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation of informed set of options to choose from. Therefore, I believe we are able to choose what to focus on right now and defer the rest.”

• For criticism over philosophy. “Yes, I recognize that we’re getting snapback to our old habits. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation of cultural/structure changes. Therefore, I believe now is the right time to add more substance to the change by blending in some structural/cultural elements.”

• For criticism over leadership. “Yes, I recognize that I asked a lot from all of you. And on the other hand, we’ve set a foundation of growth we can be proud of. Therefore, I believe now is the right time to reflect on our own personal leadership journeys.”

As the champion of agility, your job is to tell a change story that inspires and motivates, but that is also is credibly grounded in reality. This is not easy, but it is doable. And if the “Yes, And” template doesn’t sufficiently address a given critique, there is another reliable technique to try.

Framing the Change Narrative

In fiction storytelling, there are several ways to set up a story. One of the most recognizable is called the frame narrative, and the best way to explain it is with an example.

As the movie Forrest Gump opens, we see Forrest sitting on the iconic bus stop bench.3 When a stranger sits next to him, Forrest proceeds to shares a solid hour’s worth of flashbacks on his life, including his football years, his fighting in Vietnam, his running across the country, and his complex relationship with heartthrob Jenny. Eventually, the story catches up to the present day, where he’s sitting on the bench, eagerly anticipating the reunion with Jenny. The flashbacks have created the tension, the excitement we feel for the rest of the story. The present, then the past, then back to the present with more context. The present frames the past.

From Fictional Stories toward Change Stories

When it comes to telling the change story, we do the same thing, with a twist. In fiction, context is created by the past. In change, context is created by the future. The present, then the future, then back to the present with more context.

1. Clarify their perception. Sometimes people voice their concerns inelegantly, especially when they’re frustrated or fearful. A simple follow-up question will allow you to get more data about the problem and avoid reacting to the poor packaging of the problem.

2. Acknowledge the present. This is empathy for the pessimist. Whatever the anxiety or objection, there’s almost always a grain of truth. Calling it out and giving it air gives you credibility.

3. Envision the future. This is the time for the optimist. You have to believe there is light at the end of the tunnel. If you don’t believe it, why should they? This is where you shine the light.

4. Connect the future and present. As before with Forrest Gump, now we can go back to our change story with a deeper context. Close out the narrative by returning to the task at hand.

Let’s see how this framework of framing works in action.

Framing the Bank’s Broken Agility

I knew it was going to be a tough meeting.

We were already a few weeks into the onboarding of the several hundred people needed to deliver this complex banking technology project in half the time needed. Every day they were seeing things that violated their agile sensibilities.

It was time to gather all the change agents into a private meeting. I had spent some time reflecting and preparing talking points. Now I had to communicate a narrative that would keep people moving forward but also keep them from losing their minds.

Clarify Their Perception

I opened the meeting. “Okay, gang. We’re here to roll up our sleeves on the use of modern delivery methods to achieve the challenge put before us. Remember, we have a lot of work to do, so we may have to choose our battles. That said, what are you seeing there that worries or frustrates you?”

And boy, did they let me have it.

“How can you justify a three-month planning phase? That’s literally the opposite of iterative prototyping and incremental delivery. We’re not allowed to begin delivering any work until the retailer agrees on literally everything to be delivered?”

“I was hired to facilitate and empower a Scrum team, but I have not yet been assigned a team. Why am I here?”

“Heck, the team I was assigned doesn’t even honor my role. Their manager is overruling and contradicting me in every meeting. Doesn’t he know I’m here to help him?”

“Why are we estimating this backlog? Why measure the work in man-weeks when everyone knows that time-based estimation is unreliable?”

“Jesse, it’s so bad, the bank’s agile transformation office said we will not be listed as an official agile project, because ‘endorsing your approach will set the wrong tone for agility in this organization.’”

Acknowledge the Present

I responded with empathy, as well as offering some additional causes for their frustration they may not have realized.

Yes, the majority of people on this program do not understand or appreciate your role. That’s because, unlike you, they have no expertise or experience using modern methods. It will take time for us to teach them.

Yes, many of you do not yet even have a team. That’s because we are still staffing up our teams. Until you have a quorum of people on a team, we can certainly use your help getting other existing teams moving on the backlog.

Yes, we’ve been asked to document a backlog of work we know very well will change as we move forward. That’s because we have two organizations, both with perfectionist cultures. We have a long way to go to guide them to a better balance of planning and doing.

Yes, we’re using traditional estimation techniques. That’s because we simply don’t have time to teach those strange and different agile estimation practices.

Envision the Future

Despite all that yuckiness, there were some very real bright spots I could see. So I shared them.

The good news is we have a lot to work with:

• The bank and the retailer are highly committed to working together. That “customer collaboration” value is very much in play.

• There is a lot of demand in customer-driven product development using techniques like customer journey maps, story maps, and a backlog taxonomy.

• The management team have designed pods, real teams that each involve all the critical departments.

• Those cross-functional pods are also generating their own estimates.

In some respects, we’ve already had an impact building an agile mindset. If we build on that, we can get to the other aspects that are missing. Specifically, leadership believes passing the next funding milestone will give us the green light to begin more iterative and incremental delivery.

Connect the Future and the Present

Then I brought them back to reality:

The key is to build a just barely sufficient backlog to pass the next funding milestone. If it’s okay, I’d like to focus the rest of our workshop on that topic.

Not a Silver Bullet

That message served as just enough air cover for us to move forward. We held several virtual training sessions, we leveraged the collaborative spirit on the program to generate a backlog, and we hit the short-term deadline for a funding review.

To be clear, there were still plenty of bumps and bruises along the way. A few staffers did leave the program, and the program’s future was still very much up in the air. But it was a start. It was a vision. It was me taking ownership of the job I was given. To craft a message was just barely sufficient to keep the vast majority of people focused less on the frustrations of “bad agile” and focused more on the goals at hand.

This was just my story. For the rest of this chapter, we cover several other common criticisms you may come across. I’ll show you how to frame a change story that contains some grounding pessimism and some inspiring optimism.

Common Criticisms

Now that we’ve seen the reframing technique in practice, let’s examine how our personas could reframe the change narrative in the face of withering criticism.

Emmit Responds to Criticism over Impact

Earlier in this book, we talked about the need to let go of control of your transformation in order to achieve greater impact. When you’re ready to take that step, we will praise and encourage you as you aspire to move to the next stage. However, until you get there, you might get some flak for going forward alone.

Emmit has been piloting fancy techniques. However, his boss, the COO, has some concerns that it’s a waste of time and a distraction. She says, “I’ve seen this movie before, and it doesn’t go well. I don’t want your team losing focus on core services.”

Clarify Their Perception

Emmit starts with, “That sounds reasonable. Are you concerned that we’re doing a lot of things, but our mindsets have not yet changed to a new way of being?”

The COO replies with new input: “No, it’s understandable that mindset change takes time. Rather, I’m skeptical there’s any value to your team using these techniques in a silo, unless you have the whole organization doing them as well, and we’re just not ready for that scale of change.”

Acknowledge the Present

Emmit replies, “That is a fair point. It would be ideal if our whole group was able to collaborate together. We’d be able to speed up work moving across all the departments. My team’s improvements will not have that kind of impact. Moreover, I agree with your point about readiness. Jason, Marcos, and Cindy all have their teams doing a lot right now, and an organization-wide improvement effort would be a distraction.”

Envision the Future

Then Emmit appeals to what motivates the COO: results and risk aversion. “However, there is a method to the madness. First, I believe our talent can find some real opportunities on the ground, just in customer service alone. I don’t want to jinx it, but initial indications are rather promising. Second, these new ways of working should only be shared with the other leaders if we’ve first proved they can add tactical value. Given the other leaders don’t have my familiarity with agile methods, I don’t think they should take the risk of change until I’ve first validated my hypothesis.”

Connect the Future and the Present

Emmit continues, “I’ve put guardrails in place that ensure they can experiment a little and still hit their targets. We’re moving forward cautiously. You know me well enough to know I take my targets seriously. If you give me a little leeway here, we’ll have more information soon enough to see where it goes.”

Ted Responds to Criticism over Practices

In chapter 4, we discovered two key principles to help us position our poor practices within a bigger picture:

• Find your legs as you crawl, walk, run into the practices.

• Find your own agile practices that fit your context.

These principles will help you own the fact that you’re using these methods in an unconventional way. Here’s an example of how crafting a crawl, walk, run story can change the perception of those poor practices.

Team lead Ted has a new addition to the team, Geri the Genius, who says, “I’m new to this team, so I’ve waited a week to highlight this problem. But based on my experience, I can tell you that’s not a proper Kanban practice. You’re missing half the data.”

Clarify Their Perception

Ted starts with, “That sounds interesting. Are you concerned that we’re not tracking blockers?”

Geri replies with new input: “No. That’s not a problem; we can just talk through those in our daily stand-up. Rather, I’m frustrated that you’re only posting maintenance requests. Unless you put all the work up there, we can’t see the flow, and that’s the whole point of the technique.”

Acknowledge the Present

Now Ted sees where to take the conversation. “That is a fair point. It would be better for our own internal work assignments if we posted all our work in the same place. However, you may not know that our boss is very anxious about doing that. This board is very visible, and if we put our whole mess up there, he’ll get heat he’s not ready to handle.”

Envision the Future

Ted continues, “Instead, we’re moving forward cautiously. First we’ll get good at visualizing, expediting, and measuring those maintenance requests. Meanwhile, we’ll get better at slicing our projects into smaller work items, and gradually add a few of those smaller items on the board. Eventually, we’ll have both habits and data that are credible enough to include all our work in the technique.”

Connect the Future and the Present

Ted concludes his pitch: “So, we’ve agreed as a team to suffer the short-term annoyance of slower projects and broken Kanban, and work our way to a better place. I take comfort in knowing the deeper principle of the Kanban method is to start where you are and get better one small step at a time. Is that something you can support?”

Maria Responds to Criticism over Leadership

In chapter 7, we saw Brian’s journey to overcome imposter syndrome. On the other hand, some of us are brimming full of confidence, barreling forward with our own ideas and emotions, and create unintended impact on the teams we influence. In either extreme, your agile-minded boss may not appreciate the time it’s taking you to grow into the right mindset.

Let’s say Maria is tasked with driving the agile transformation, and the conversation gets awkward when her boss, the vice president, says, “I’ve called you in here because I’m concerned about how you’re doing in your role. You’re making great progress installing some of the processes. But you’re too assertive with this change effort.”

Clarify Their Perception

Maria knows this is going to be tough. “Okay, I’m listening. Can you give me an example?”

The VP dives right in and shares a recent complaint: “Well, one project manager came to me last week rather shaken. He shared how the two of you got into an argument during a kaizen meeting. He was asking me whether I’d heard about the episode and whether he’d done anything wrong.”

Acknowledge the Present

Maria knows it’s time for some candor. “Yes, that happened, and I know who you’re talking about. He made a point that his suggestions haven’t been implemented by the change committee, and I just … I just reacted. I didn’t realize it at first, but eventually I felt bad about shutting down the conversation. I apologized to him privately on Monday, and we came up with some ideas for moving forward. I’m sorry the timing of the events got you involved. The truth is, I’m aware I have some liabilities that are impacting my effectiveness.”

Envision the Future

Maria continues, “For the last couple months, I’ve engaged an executive coach, at my own expense. My coach is helping me surface a handful of insecurities I didn’t even realize I had. They started after I took this role. Between the change resistance, the dilution of the practices, and the demands for support, I’ve had to juggle more frustration than ever before. The good news is I’m starting to catch my anxieties before they show up as reactions. Last week was one that got away from me. I’m trying to be honest about the journey. The hope is by doing so, I can rebuild some relational capital. Heck, it might even serve as an example to others of the personal growth this transformation can require.”

Connect the Future and the Present

The VP’s body language shows him to be intrigued, so Maria continues. “Listen, I appreciate the accountability. I need as much feedback as I can get on this. I know I can only serve in this role if I do it well, and I don’t want to be a liability. If you’re willing to let me, I’d like to keep going into the challenge.”

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve tackled what to do when your boosts all incur recurring criticism and unfair perceptions. To craft a better story, we’ve learned about:

• Half empty, half full. The mindsets of a prisoner of war and an improv performer are strangely, similarly effective. Yes, acknowledge the unexpected, unwanted reality. And add a creative, positive step forward.

• Framing the change narrative. The same storytelling technique used in the movie Forrest Gump can be adjusted to tell the fuller story of your transformation.

• Responding to common criticisms. It turns out the specific criticisms are not the challenging part. All of them can fit the talking point techniques we’ve explored. The hard part is knowing the deeper truths you are marching toward. If you know that, you can take the heat with more confidence.