Chapter 1

Roots of Western Urban Form: Centralization

This chapter focuses on key points in the evolution of human settlements that, while reflecting very specific times, cultures, and conditions, also serve as the roots of America’s planning and urban design traditions.

First Cities

Early organized societies: Organic cities

Whenever archeologists think they have identified the oldest human settlement, it seems that a dig somewhere else unearths an even older one. Each new find adds to a rich human tradition: Cities exist because humans are social beings, variously tribal, communal, and mutually supportive. From nomadic beginnings—first hunter-gatherers, then tribal herdsmen—came agricultural settlements that eventually clustered for religious, administrative, defensive, or economic reasons. With the emergence of surplus economies, hierarchical societies appeared and supported the growth of villages, then towns, and, finally, cities.

In simplified terms, two basic city forms emerged early in Western civilization: the organic and the geometric.1 Organic cities arose by chance and accretion; they grew willy-nilly. Geometric cities were typically planned, functional, and rational. Geography, climate, and land apportionment shaped both forms, whether in an administrative center in a Mesopotamian kingdom, a trading settlement on the Silk Road, a Mexican colonial outpost, or a farming community on the Canadian plains.

Likely the more ancient of the two, organic settlements developed around regional crossroads, safe harbors, river crossings, and access to mountain passes or other geographic features crucial to trade or defense. Sometimes an expanse of arable land, reliable access to water, and a good defensive position encouraged settlement. From these beginnings, streets and public ways arose from the paths people and animals traveled, guided by topography. Original settlement patterns, allotment by rulers, negotiation, and trade likely governed land distribution. Often the result was a radial-concentric plan, as small villages merged and, eventually, formed into a town and then a city. Venice and Siena in Italy fall into this category, as do some newer cities, like Boston.

Stronger political, social, and religious organization: Geometric cities

The geometric city form was intentionally designed in some fashion; it dates to at least 2600 BCE. The cities of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa in the Indus River Valley are two early communities that comprised blocks formed by streets running at right angles.2 Rectilinear patterns also appear in excavated towns in Babylon and China that date from the seventeenth to fifteenth centuries BCE. The Egyptians also knew geometric planning: Kahun (nineteenth century BCE) and Amarna (fourteenth century BCE) each follows a rigid gridiron plan, as much for religious reasons as for the speed and mechanization such a plan allowed. Lewis Mumford writes, “City building under the pharaohs was a swift, one-stage operation: A simple geometric plan was a condition for rapid building. . . . More organic plans, representing the needs and decisions of many generations, require time to achieve their more subtle and complex richness of form.”3

Such considerations indicate a more mature society—one that has outgrown purely organic roots. They also suggest authoritarian rule. Geometric settlements were often planned in advance as central places for religion and commerce, remote outposts for control of regional populations, or colonial encampments that prioritized defense and control in their design. The grid offered a practical method for allotting land in colonial settlements and for demarcating land according to use and function.4

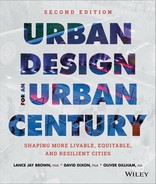

The Greek city of Miletus in Asia Minor offers one of the best-known early examples of geometric planning. While Greek cities on the mainland tended to develop along topographic contours in an organic pattern, Greek colonies in Asia Minor and elsewhere followed a more geometric path.5 Rebuilt in the fifth century BCE after having been razed during the Persian Wars, Miletus spread out on a gridiron around a central, rectangular agora in a plan often attributed to Hippodamus. This organizing scheme proved so compelling that it took on the city’s name—Miletian.

As the Greeks spread westward along the Mediterranean’s shores, they exported the Miletian plan to their outposts in Italy, where the Romans later adopted it. From their rise to power until the demise of their empire in the fifth century CE, the Romans built numerous cities and towns on the Miletian plan throughout what is now Western Europe. These communities, often fortified outposts called castra, usually followed the same strict grid pattern around a central forum. Sometimes they were overlaid atop preexisting settlements of other cultures; cities as distinctive as Cologne, Florence, and London all grew from such beginnings. In Tuscany, behind massive sixteenth-century walls, the historical center of Lucca still preserves its original Roman street grid.

1.1 Plan of Miletus (fifth century BCE). Reconstruction of the Greek colony in Asia Minor—carried out after being sacked by the Persians—followed a gridiron plan, with square blocks radiating from a central agora. As they established subsequent colonies around the Mediterranean, the Greeks replicated the Miletian plan.

Courtesy Holger Ellgaard, via Wikimedia

1.2 Dubrovnik, Croatia. The Byzantine empire inherited the Miletian plan from Rome and prescribed the grid that still distinguishes Dubrovnik’s historic center from development outside its walls, which were begun in the ninth century and completed during the Renaissance.

The classical cities that developed from these two beginnings evolved over hundreds and thousands of years. Rome itself combines organic origins and gridded streets, and historians have identified at least six layers of reconstruction, with the Roman grid absorbed into successive periods of growth and decay.

Rebirth of European Cities: “Organic” Cities of the Late Middle Ages

Few new European cities arose in the centuries after the fall of Rome, and military considerations strongly shaped those that did, primarily bastides in France and Zähringer towns in Germany. Inspired by Roman military outposts, these towns followed a strict Miletian pattern arrayed around a central market square. Planned from scratch, they exemplified medieval town planning and urban design.

Bastide towns dotted the Languedoc, Aquitaine, and Gascony during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the Hundred Years’ War between France and Britain raged over much of France. Bastides were typically planned and built as single units, often by a single lord; Alphonse of Poitiers for example, built several in a bid to consolidate territorial control.6 Roman influences remained strong in medieval France, and the bastides adopted the plan of the castra that preceded them. Wide streets at right angles crossed a central marketplace, dividing the town plan into super blocks, or insulae, which were further divided by narrow lanes. Among other things, the grid plan’s modular character facilitated tax collection and record keeping,7 considerations that encouraged its use in later centuries.

The dukes of Zähringer built fortified towns in Germany’s Rhine Valley in the twelfth century, seeking, like Alphonse of Poitiers, to tighten control over their domain.8 Freiburg, Villingen, and Rottweil survive as examples of the form and, as in France, drew heavily on the model of the castra, with a Miletian grid plan built out from a central marketplace.

What might be characterized as medieval urban design extends beyond bastides and Zähringer towns, however. Cities during the same period, some dating to antiquity, undertook major renovations and expansions that resulted in some of Europe’s most renowned public spaces. From its beginning as a small plaza facing the Basilica di San Marco in Venice, the Piazza San Marco took on its present configuration in the twelfth century, when it was rebuilt to accommodate a historic meeting between Pope Alexander III and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa). The piazza continued to grow incrementally; the doge’s palace, the clock tower, and the campanile were added between the fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries.

The Piazza del Campo in Siena sits on gently sloping ground between the three original settlements that make up the present-day city. The piazza we see today dates largely from reconstruction carried out in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the Palazzo Pubblico was completed. While the piazza may seem like the quintessential medieval space in the quintessential medieval city, it pointed toward a major functional change. Unlike the Piazza San Marco and other medieval public spaces that served as forecourts to great cathedrals, the Piazza del Campo serves no religious building; it focuses instead on a civic building, the Palazzo Pubblico, prefiguring the Renaissance and the beginnings of modern secular civic space.

1.3 Piazza del Campo (fourteenth century), Siena, Italy. The Piazza del Campo broke with an important medieval city-building tradition. Instead of serving as the setting for a cathedral, the piazza’s focus is a secular building, the Palazzo Pubblico, seat of the Sienese republic. The square prefigured the modern idea of secular civic space.

Courtesy Manfred Heyde, via Wikimedia

Reintroduction of Classical Learning: “Geometric” Cities of the Renaissance

In Europe, the Renaissance revived interest in the great civic works of classical Roman architecture, sparked in part by wide distribution of De architectura, a rediscovered treatise written by the Roman engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (first century CE). The new awareness of classical architecture reflected an emerging humanist worldview that heavily influenced European ideas about cities, as demonstrated in Pienza in Tuscany. Designated a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site in 1996, the diminutive city serves as a prime example of early Renaissance city planning. UNESCO’s citation praised the town’s “outstanding universal value” as “the first application of the Renaissance Humanist concept of urban design, and as such [it] occupies a seminal position in the development of the concept of the planned ‘ideal town’ which was to play a significant role in subsequent urban development in Italy and beyond.”9

Pienza owed its transformation to Pope Pius II, who, in 1459, launched a rebuilding of the center of his native town in conformance with emerging Renaissance principles. To direct the work, he hired Bernardo Rossellino, a follower of Leon Battista Alberti, whose approach to architecture foreshadowed modernity in many ways. In addition to advocating the conscious creation of public places, he and his followers recommended the prohibition of buildings housing noxious and noisy activities, such as tanneries and slaughterhouses, within town precincts. Instead, he suggested the creation of dedicated districts for craft and industrial use—an early instance of land use zoning. Rossellino brought to Pienza a new vision of urban space that culminated in the creation of Piazza Pio II and its surrounding buildings, including the Piccolomini palace, the Borgia palace, and a pure Renaissance exterior for the medieval cathedral.

In Alberti’s wake came a parade of Renaissance theoreticians, from Andrea Palladio to Sir Thomas More, whose writings ranged from purely physical design to the philosophical bases for building. Ideal cities such as Palmanova in northeastern Italy and More’s literary utopia, both from the sixteenth century, served as models for centuries of town planning to follow.

While More’s Utopia imagined an ideal society set in an island nation of reasonable, tolerant, and peaceful people, Palmanova originated in a more bellicose world. Built to defend Venice’s eastern flank against Turkish attack, in plan view the city resembles a nine-pointed star, with a focal piazza surrounded by radiating streets. The unusual form grew from the need to command multiple defensive bastions from a central location and to move troops among the bastions quickly and efficiently.10 Military origins aside, Palmanova’s geometry clearly reflected an idealized plan. Its authoritarian pattern, arrow-straight streets, and imposition of human order on nature foreshadow baroque city planning. Those same traits also reflect major advancements in surveying, which allowed the drawing of scaled plans for designing new cities. Ironically, this small military outpost influenced planning for generations. Its pure geometry and containment within a greenbelt of earthworks inspired planners and designers as diverse as Ebenezer Howard and Paolo Soleri.

1.4 Palmanova, Italy (1593). The strict geometry of the plan for Palmanova—a defensive fort east of Venice—grew out of military necessity, but it influenced town planning for centuries. Its straight, wide boulevards and idealized plan surfaced in baroque-era plans across Europe. Purely geometric inside a broad band of earthen bulwarks, it also inspired designs as varied as English garden cities and twentieth-century visionary projects like Arcosanti in Arizona.

From Civitates orbis terrarum, a sixteenth-century atlas of cities published by Georg Braun and Frantz Hogenberg, via Wikimedia

Architects Vincenzo Scamozzi and Pietro Cataneo also created city schemes that influenced later urban plans. Reviving the classical works of Vitruvius in his L’Architettura (1567), Cataneo plotted idealized grid cities peppered with public squares. Even though Cataneo himself saw few of these plans built, they were realized in towns like Charleville in northern France and Avola in Sicily, and they served as models for American cities like Philadelphia and Savannah, Georgia.11

By the seventeenth century, the urban ideas of the Renaissance had matured into those of the baroque and had spread across Europe. Like baroque architecture, the urban plans of the era favored artifice on a grand scale, with sweeping vistas and long axes slashed through crowded cities. A zeitgeist dominated by absolute monarchies and the Counter-Reformation strongly influenced European city-building in this era. Rulers and their architects attempted to impose a new sense of order upon the accretive muddle that characterized many European capitals. This new order frequently included an authoritarian preference for straight avenues and clean lines of sight, an inclination reinforced by many planners’ backgrounds in military engineering.12

In some respects, the work of these baroque engineers shared the instincts of the U.S. urban renewal era more than four hundred years later. It did not seem to bother Italian military engineers of the time, Lewis Mumford writes, that the “encumbrances” they ordered removed “were human households, shops, churches, neighborhoods.” The fact that this “tissue of habits and social relations” could not be replaced “did not seem important to the early military engineer any more than it seems so to his twentieth-century successors, in charge of ‘slum clearance projects’ or highway designs.”13

This unfortunate parallel may hold true, but this era also gave birth to some fundamental concepts of modern urban design: the idea of the street as a spatial element in its own right; the concept of purposely shaped and defined public space and street networks organized by visual foci; and the idea of deploying buildings with uniform facades to define streets and other public spaces.14

Beyond the development of new concepts, urban conditions required new approaches in the baroque era as the populations of cities swelled dramatically, often overwhelming the functional capacity of medieval street systems. Like planners in later periods, the era’s city builders worked to bring public health, light, and air into the city, to clear hopeless gridlock, and to bring order to perceived chaos.

Early in the seventeenth century, Pope Sixtus V worked with the architect Domenico Fontana to devise a new master plan for Rome.15 The plan introduced a network of long, straight avenues connecting the Porta del Popolo to churches, monuments, and formal public spaces, among them the basilicas Santa Maria Maggiore (St. Mary Major) and San Giovanni in Laterano (St. John Lateran) and the Colosseum. Sixtus’s plan created what Edmund Bacon calls “a controlled sequential experience” out of what is basically a “movement-system design structure.”16 Demarcated by a series of obelisks erected by Sixtus, the system served as the principal framework for city-building in Rome for several centuries. Such significant public spaces as the Piazza del Popolo, the Piazza Barberini, and the Spanish Steps were later designed and built around this framework.

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini’s acclaimed Piazza San Pietro, which superbly rationalizes the entrance sequence to the Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano (St. Peter’s Basilica), stands as a preeminent example of baroque planning and design. Bernini designed the colonnade and piazza around one of Sixtus’s obelisks in another nod to the pope’s vision for Rome. Combining an understanding of perspective inherited from the Renaissance with the baroque penchant for illusion and grandeur, Bernini ingeniously blended oval and trapezoidal plans to foreshorten perspective and make the cathedral seem closer to the piazza than it actually is.17

Baroque urbanism also broke new paths well beyond Italy. In France, the expansion of the Château du Louvre and the development of the Tuileries Garden both exhibit baroque preferences. Not satisfied with those projects, Louis XIV built Versailles and relocated his court there toward the end of the sixteenth century, replacing the Louvre as the royal residence. The axial layout of Versailles and the long perspective vistas of André Le Nôtre’s gardens rank among the foremost examples of urban design and landscape architecture from the baroque period.

In 1660, England’s Charles II hired Le Nôtre to plan London’s Pall Mall. The Great Fire of 1666 provoked a flurry of proposals for rebuilding the entire city from architects and planners, including Sir Christopher Wren and John Evelyn. None was actually implemented, but most displayed the strong influence of Continental designers like Le Nôtre. In submitting his plan to Charles II, Evelyn invoked three principles for the proposed reconstruction: “beauty, commodiousness, and magnificence.” The last principle most clearly reflects the baroque tradition, and Evelyn’s plan of gridded streets broken by long, axial diagonal avenues clearly follows contemporary examples from the Continent.

England exported the ideas it had absorbed from the Continent to its possessions abroad. The Regional Plan for the Ulster Plantation was produced in the early seventeenth century as part of the colonization of Ireland. In a 1614 master plan for the walled city of Derry (now Londonderry), baroque planning principles define the streets and square that make up “the Diamond.” The design of space surrounding key public buildings—such as St. Columb’s Cathedral and the Bishop’s Palace—received careful attention. As buildings (designed in the emerging baroque architectural style) began to fill in the dictated street pattern, they formed collective walls that reinforced the public spaces.18

1.5 Piazza San Pietro (1656–67), Vatican City. Bernini’s quintessential baroque plan for a plaza and colonnade masterfully blends Renaissance knowledge of perspective with the baroque penchant for grandeur and illusion to orchestrate the experience of approaching St. Peter’s Basilica.

Courtesy Jalesee, via Wikimedia

Spain sent baroque European planning ideas to its cities in the New World, as did other colonial powers. In fact, the urban design principles that emerged in the baroque period came to dominate city planning and urban design in both Europe and the New World over the next three centuries. The same ideas of axial public streets and landscaped boulevards; radial and diagonal patterns defined by specific visual focal points; monumental public spaces; and uniform street walls characterized Pierre-Charles L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, D.C., Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s plan for Paris, and many other urban plans and expansions in both Europe and the Americas. But baroque planning of another sort, borrowing heavily from the Miletian tradition, ultimately wielded the most influence in North America.

The Emergence of Merchant Cities: Integrating Renaissance Ideas and the Marketplace

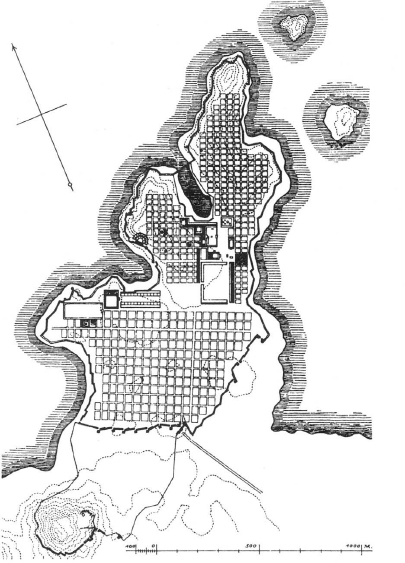

In the Netherlands, Amsterdam in 1607 adopted the Plan of the Three Canals,19 which called for a quadrupling of the city’s area with the construction of three new encircling canals that would also serve as the main streets of new districts. The plan’s innovation lay not only in these combined canal-streets but also in its incorporation of phased execution over a long period of time: each canal would serve as the outer boundary of the city in successive enlargements. In its long, straight canals and streets, and its radial form, the plan created a spiderweb pattern that drew heavily on baroque planning in other parts of Europe. Yet it also relied upon a distorted version of the ancient Miletian grid (borrowing slightly, perhaps, from the earlier plans of Pietro Cataneo).

The grid form supported another innovative quality of the plan: its joint execution by public and private actors. The municipal government drew up a plan that parceled out the land in a grid of blocks, established firm guidelines for the use and form of the buildings along the canals, and reserved specific areas of land for churches and marketplaces. That done, the government pulled back and left build-out largely to the private sector—often investors working for profit.20 This approach prefigured the planning of North American cities. Gridded expansion, phased construction, and a combination of public and private enterprise all anticipated the methods that American cities adopted in subsequent centuries.

1.6 The Plan of the Three Canals (1607), Amsterdam. The Three Canals Plan, adopted by the municipality, introduced a baroque sense of geometry and order into expansions of the medieval city. Amsterdam’s novel approach to the plan’s execution proved influential in the United States: the municipal government identified the plan area and set guidelines for construction, but it left realization of the plan to private developers.

Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

The Grid Reaches the New World

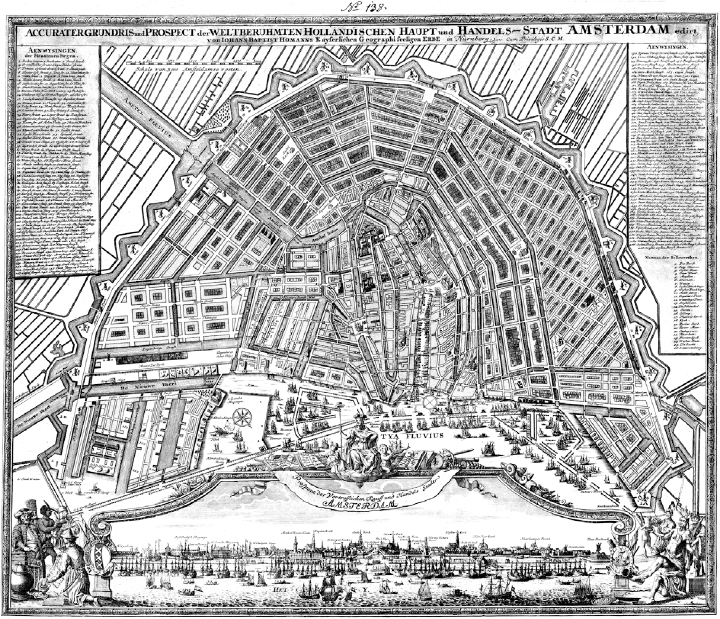

Amsterdam, in fact, served as a model for one of the New World’s most important cities. In 1626, less than twenty years after the Plan of the Three Canals, the Dutch West India Company decided to consolidate its scattered North American trading outposts into a single defensive settlement called New Amsterdam at the southern tip of the island of Manhattan.21 At the time, the Dutch claimed all of the land between Virginia and French Canada as part of their colony of New Netherland, but by the 1640s settlers from New England had begun planting small towns on both shores of Long Island Sound, moving ever closer to New Amsterdam. Within twenty years the trickle of English settlers into New Netherland had become a flood, and in 1664, after a brief military assault, control of the colony passed to the English, who renamed the town in honor of the Duke of York.22

New Amsterdam may have started out as an organic, somewhat chaotic settlement, but that changed under Peter Stuyvesant, governor of the colony from 1647 until its handover to the English. By the time the Duke of York’s troops arrived, Stuyvesant had transformed the town plan into a miniature version of its namesake city. In a move worthy of baroque European planners, the governor had imposed a lattice of new streets over the “town’s confounding jumble of lanes and footpaths.”23 He also built a canal and a dock, repaired the colony’s fort and northern defensive wall, and established rudimentary building and sanitary codes. The result was a curved grid of streets, blocks, and a canal not unlike those of Amsterdam’s 1607 plan, albeit much less dense and on a far smaller scale. However primitive, this pattern entered the settlement’s DNA, and the English continued the grid pattern, although with distortions. When the city’s population mushroomed in the nineteenth century, the grid devoured the surrounding landscape, taking on the rigidity and uniformity that characterize New York City today.

Grids influenced the form of other English colonies. In 1683, shortly after William Penn received a grant for what became the Colony of Pennsylvania, Thomas Holme published a plan for its urban center—a deliberate grid aligned on an east-west axis running between the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers. Holme, a surveyor, collaborated with Penn on the plan, which laid out the pattern for the city’s subsequent growth. In promoting an orthogonal plan right from the beginning, the team showed vision far beyond that of the Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam. Indeed, the Philadelphia plan bore the hallmarks of the idealized grid cities of the Renaissance envisioned by Cataneo. The purposeful placement of public squares and axial streets made Holme’s simple diagram an almost utopian vision for Penn’s planned community of Quakers.24

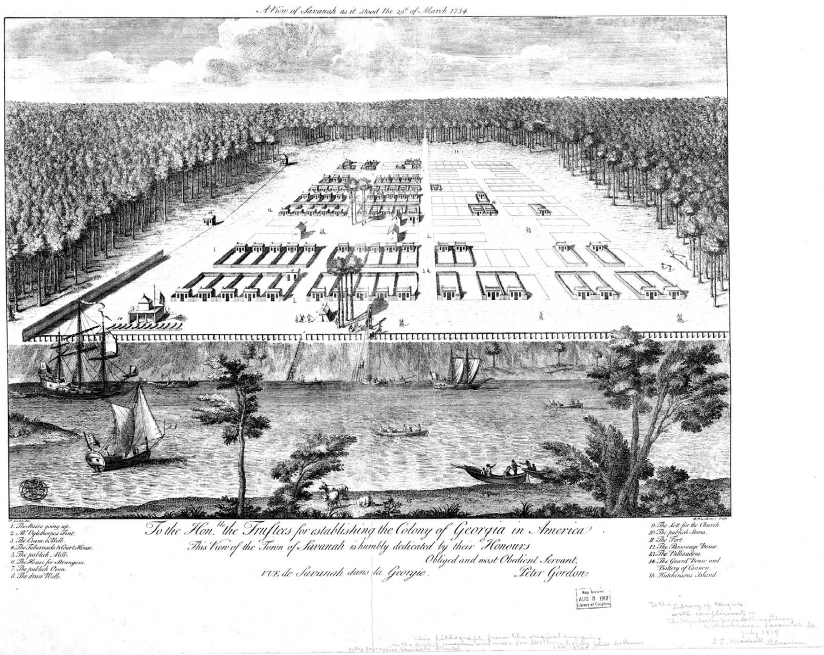

The grid plan for another early American city, Savannah, Georgia, proved even more sophisticated and visionary. Earlier settlements in the southern English colonies generally avoided grids, but Savannah and Charleston, South Carolina, embraced them. Laid out in 1733 by James Oglethorpe, Savannah largely followed Cataneo’s plans for ideal cities, with a pattern of blocks centered on public squares. Each square anchored a cell of eight blocks, with the east and west ends of the square appointed as sites for churches and other public and commercial buildings. The plan reserved other lots for residential use. The Savannah system carried out a political function as well, with each eight-block cell representing a political unit of landowners called a ward. The settlement began with four such wards in the middle of a forest on the banks of the Savannah River. Those four wards fixed the pattern of the city’s growth for more than one hundred years.25

1.7 Plan of New Amsterdam (1660). In nearly twenty years as governor, Peter Stuyvesant turned New Amsterdam’s jumbled lanes into a gridded pattern that suggested the influence of both the Three Canals plan and baroque planning sensibilities.

Courtesy of I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox & Tilden Foundations

Not every American settlement started out in such an organized fashion. Boston, settled in 1630, had no planned layout and retained a largely accretive, organic character for more than two centuries. Early maps of the city do suggest a loose and distorted grid, but a true and regular orthogonal pattern did not appear in any major way until the construction of the Back Bay on filled land in the mid-nineteenth century. But Boston remains a notable exception; the Miletian approach ultimately dominated in American city building.

Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that grid geometry represented the democratic principles upon which the new nation was founded, a belief that reflected the fundamental role real property played in the American idea of democracy. The founding fathers—themselves all property owners—saw holding real estate as a fundamental right of each citizen. They established ownership as a precondition to voting in the early nation, in part because having land seemed likely to ensure economic freedom in an agrarian economy. Such freedom remained unattainable in Europe, where only a privileged few owned land. The new democracy encouraged widespread distribution of land—a commodity the United States happened to have in abundance.

1.8 View of Savannah, Georgia (1734). Although not every English settlement in the American colonies adopted the grid, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah embraced it. The visionary plan for Savannah arrayed eight blocks around a central square to form a physical and political unit, with appointed sites for public functions like markets and churches; the rest of the land was reserved for houses. These units (or wards) remained the building blocks of the town’s growth for more than a century.

Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

Jefferson did much to devise the land-distribution process. He proposed stretching a surveyor’s grid of ten-mile squares across the nation’s undivided territories; aligning each square with its neighbors would ensure that no land was left vacant. In organizing toward these ends, Jefferson saw himself as the designer of a landowning—and hence orderly and self-regulating—democracy. When Congress passed the legislation for disbursing land, it altered Jefferson’s original plan by creating “townships of six miles square” subdivided into thirty-six sections of one square mile each. The land was to be sold at public auction by section at a price of one dollar per acre, or $640 per section—the smallest parcel that could be bought at the time.26

Whether relying on a six- or ten-mile basic unit, the work and theories of Thomas Jefferson guided the parcellation of the United States’ seemingly endless common realm. Congressional surveyors cast a vast, rectilinear net over the wilderness—imaginary grid lines that eventually stretched from the Appalachians to the Pacific, heedless of topography, geology, water, soils, vegetation, or wildlife. That grid became the framework for dividing the continent into individual plots of land and placing them in private hands.

Some of the surveyors’ work remains visible today. A flight over the flat lands of the Great Plains shows sections clearly defined by property lines and roads. It is even possible to pick out the points where surveyors adjusted for the convergence of lines of longitude running between the poles. Every so often, roads that run as straight as arrows for miles suddenly make a right-angle turn where section lines shift to account for meridional convergence.

That vast geometry inevitably influenced the growth and pattern of American cities. Eventually, Americans applied grids to cities along the eastern seaboard, straightening even Boston’s streets outside its meandering core. Midwestern and Western cities like Indianapolis, Chicago, Oklahoma City, Austin, Denver, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco all grew along grids imposed from the beginning. Although the United States’ use of the grid has often been associated with a democratic political attitude—and despite Jefferson’s firm belief in it as an instrument of democracy—the grid had historically served to enforce power and control. Greek colonial cities, Roman castra, bastides, and many other examples suggest that it took meaning from the way it was applied.27 Despite Jefferson’s lofty aims, in the United States the grid came to symbolize not freedom as much as practicality and speculation.

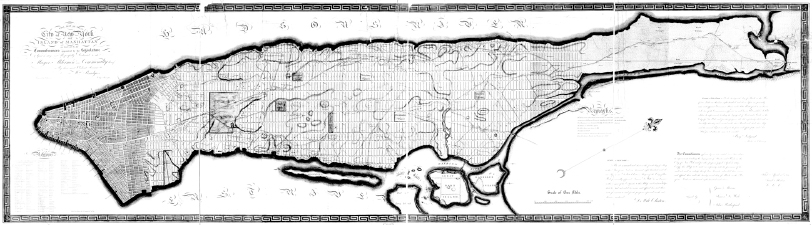

Private investors financed the building of transcontinental railroads in part by selling off sweeping tracts of public land they had been granted by the U.S. government as an incentive to complete the project. They stamped out hundreds of grid-pattern towns to parcel out the land for quick and easy sale. In 1811, a special commission chartered by the state legislature created a notorious plan for building out Manhattan: an unrelieved gridiron of regular blocks from 23rd Street to 155th Street. The plan allowed relatively little public open space (Central Park was not part of the plan, for example) or deviation from the grid—Broadway’s errant diagonal is nowhere to be seen. The commissioners declared it obvious that “straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build, and the most convenient to live in.” The commissioners’ surveyor, John Randel Jr., added that his plan offered particularly good opportunities for “buying, selling, and improving real estate.”28 In the end, plans for the gridded cities of the United States responded more to the needs of the real estate developer than the interests of the designer or the democratic idealist.

1.9 Commissioners’ Plan for New York City. The gridiron that signified order and authority to baroque-era rulers in Europe took on a more practical meaning in the United States—it made development easier. The unrelenting grid laid over Manhattan’s topography in this 1811 plan provided the framework for the city’s nineteenth-century growth.

Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

1.10 L’Enfant Plan for Washington, D.C. Pierre-Charles L’Enfant scoffed at the simple grid as too humble for a national capital, yet he relied on it as the background pattern for his baroque plan of squares threaded onto a web of avenues radiating from public monuments. Most U.S. cities stuck with a basic grid for ease of design, development, and management.

Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

The nation’s capital, however, proved an exception. To plan the new city, George Washington turned to Major Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, a military engineer trained in the European baroque tradition. L’Enfant belittled the humble grid plan that Jefferson had sketched out, stating that the plan for the nation’s capital should be “proportioned to the greatness which . . . the Capital of a powerful Empire ought to manifest.”29 Scorning grids in general as “tiresome and insipid,” L’Enfant proceeded to draw up a plan of starlike squares radiating diagonal avenues that makes up today’s Washington. In its use of long vistas centered on public monuments, the design recalls Sixtus V’s plan for Rome. In its pursuit of baroque grandeur, it looks beyond democracy to a time when the new nation might entertain imperial ambitions. Yet even L’Enfant’s bold vision rests atop a familiar background—an ever-practical, easy-to-use land-apportioning grid.

In the end, L’Enfant’s plan proved an exception to the gridded rule of most U.S. cities (although the City Beautiful movement would revive his ideas in early twentieth century). Ease of design—so easy an office boy could figure it out, said Lewis Mumford—ease of record keeping, and a mass-produced nature made the grid pattern irresistible for a speculative nation in a hurry to grow.30 It also turned out to be highly suitable for a vast industrial revolution; the grid became the foundation for a generation of high-density U.S. industrial cities.

The Industrial Revolution

Explosive growth overwhelms America’s cities

Before the Industrial Revolution, forces such as trade, agriculture, and defense determined the shape of cities in North America and Europe, whether planned or unplanned. How far a person could reasonably walk and the requirements of carts, wagons, and herds of animals heavily influenced the layout and dimensions of city streets regardless of the form the larger city took. Defensive strategy and technology also dictated form, but the resulting walls—and the need to guard them—often imposed smaller footprints than cities might otherwise have produced.

A jumble of uses marked preindustrial cities, where home and workplace were often either combined or located near one another. The inefficiency of walking great distances dictated that most land uses ended up as close neighbors, even in the most rigid of gridiron plans. No matter how noisy or obnoxious, different activities existed cheek by jowl and one atop another. Attempts to organize uses—particularly to banish offensive or disruptive ones from residential areas—rarely succeeded. Yet except for the most jarring juxtapositions—houses next to tanneries, living space over abattoirs, food markets next to fulling mills—preindustrial city dwellers generally accepted these conditions. The mix of residential and commercial uses added to the liveliness, interest, and excitement of a city.

The biggest settlements in the mid-nineteenth-century United States were largely port cities. Back in 1820, the ten largest cities included Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, and Salem—all major ports. Their populations ranged from more than one hundred thousand in New York to just twelve thousand in Salem. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 marked the first instance of an American infrastructure project influencing urban development—an impact in its day as significant as that of the interstate highway system in the twentieth century. By the close of the decade, Albany and Buffalo had both grown into major cities. Sailing ships lined wharves. The prime regulator of building height was the number of stairs a person could reasonably climb, which meant that few buildings rose higher than four stories and church steeples stood as the tallest structures on urban skylines. Noise in the streets came mostly from people, animals, and the wheels of carriages and carts.

The Industrial Revolution redrew this picture. Up to that point, U.S. manufacturers had relied primarily on waterpower and favored water for heavy transport, making rivers and streams preferred sites for operations. After the Civil War, coal and steam power replaced waterpower in industry and railroads dominated shipping. Now factories could locate almost anywhere, as long as they had access to a railroad to deliver coal (for making steam) and to carry away finished goods. But factories also needed labor, and the biggest labor pools were found in mercantile cities, where the markets for goods and the means of cross-oceanic transport were also close at hand. Suddenly, stately urban homes on quiet streets found themselves in the shadows of looming, high-decibel factories that operated around the clock. Huge new rail-marshaling yards came to dominate many neighborhoods and waterfronts.

Lewis Mumford has described the era:

Large-scale factory production transformed the industrial towns into dark hives, busily puffing, clanking and screeching, smoking for twelve and fourteen hours a day, sometimes going around the clock. . . . Extraordinary changes of scale took place in the masses of buildings and the areas they covered: vast structures were erected almost overnight. Men built in haste and had hardly time to repent of their mistakes before they tore down their original structures and built again, just as heedlessly. The newcomers . . . crowded into whatever was offered. It was a period of vast urban improvisation: makeshift hastily piled upon makeshift.31

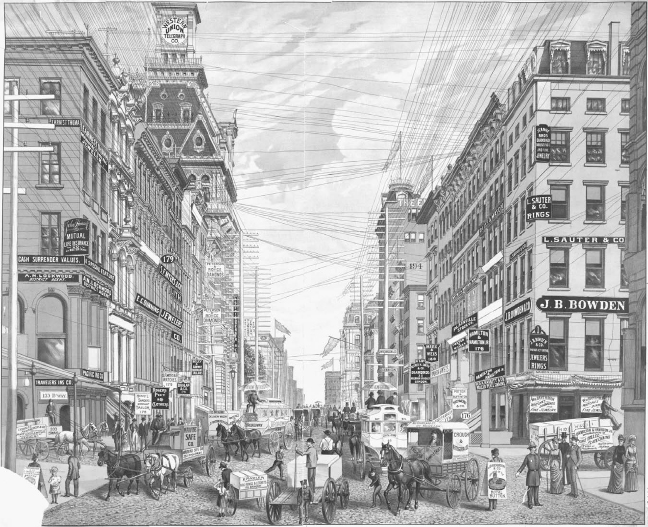

These newcomers represented a vast demographic change wrought by industry. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, most Americans lived on farms or in small towns. High factory wages and the opportunities for more varied lifestyles that city life offered gradually depopulated the countryside. The 1920 census showed that for the first time in U.S. history, more people lived in cities than on farms.32 A flood of immigrants from abroad joined this urban influx, creating crowding and chaos as cities ballooned in size. Between 1870 and 1920, New York City’s population grew more than sixfold; Chicago’s, ninefold.33 An expanding labor pool attracted more factories, further encouraging overcrowding. As in preindustrial cities, uses remained mixed together, and new housing sprouted up next to new factories. There was, at first, no other choice—people needed to get to work, and only the rich could afford to travel by horse-drawn conveyance.

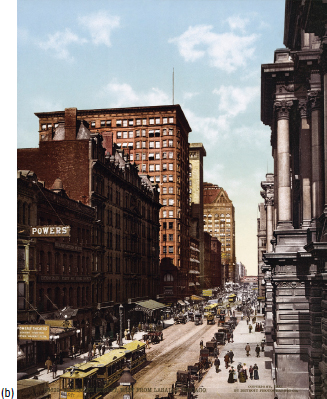

1.11 a,b In the last half of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution transformed the shape of U.S. cities. These of views of Chicago, one of America’s most heavily industrialized cities by the start of the twentieth century, suggest how much the scale and intensity of urban life had changed. In 1850, a few years before the first photo was taken, the city had 29,000 residents. By 1900, when the second photo was taken, it had 1.7 million. New forms of mechanized travel—railroads, then electrified streetcars, then subways—radically altered street design while dramatically extending the distances people could travel to work and shop. This fueled a rapid expansion of the grid pattern in cities and the annexation of adjoining communities to accommodate surging populations and expanding industries. Railroads encouraged the development of distant suburbs, sowing the seeds for later decentralization. Industrialization itself fed the trend, as people sought housing and green space away from the smoke and noise of factories.

Alexander Hessler photograph from McClure’s magazine, via Wikimedia user Bob Burkhardt. Randolph Street chromolith courtesy of Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Giving form to industrial cities: A “new American urbanism” takes shape

To the heavens: Skyscrapers

As urban populations ballooned and new businesses crowded into city centers, market pressures mounted to use land more intensively, if only to earn more money for landowners. But it took technological breakthroughs to allow buildings to rise above five or six stories, the number of flights of stairs most people could climb. Because of the climb, in fact, owners generally had to reduce rents for higher floors in order to lease them.34 In 1852, Elisha Otis invented a safety brake for elevators, removing one limit on building height.

But standard construction technology—masonry walls and wooden columns and beams—still imposed strict limits on how high a building could rise. Each new floor required substantially thicker walls on the floors below to hold the weight it added; particularly on small sites, even a few extra stories demanded so much additional bulk at the base that some lower floors became too tiny to be useful. Inventor James Bogardus pioneered the use of cast iron to fabricate both facade and internal structure in a five-story structure he built in New York in 1848–49.35 For Bogardus, cast iron opened the door to fire resistance and manufactured building parts. But in the process he stumbled on the model for the curtain wall—a structural skeleton that provided strength and stability, with walls essentially hung like curtains from the frame. Bogardus’s first building predated London’s Crystal Palace by two years. In the 1880s, experiments with ways of adding steel framing to structures in both New York and Chicago quickly bore fruit; within a decade, architects and engineers had begun to master the use of internal steel skeletons to support higher buildings without sacrificing the usable space on any floor.

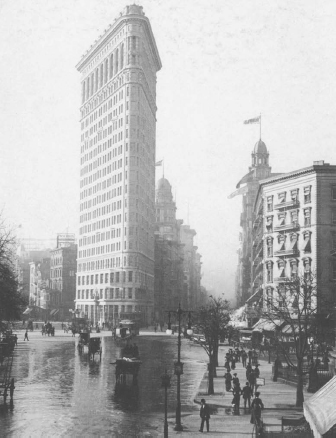

Despite these advances, the first true skyscrapers relied on the tried-and-true technique of masonry bearing walls, using metal only for interior structure. Burnham and Root’s sixteen-story Monadnock Building of 1884–92 followed this model in Chicago, but exclusively steel-framed buildings began to appear at about the same time. William Le Baron Jenney’s ten-story Home Insurance Building, built in Chicago in 1885, boasted one of the first skeletons of cast-iron columns and steel beams. Adler and Sullivan soon followed with steel-frame office towers in Chicago, Buffalo, and St. Louis. By 1903, Chicago’s Daniel H. Burnham had completed the twenty-one-story Fuller Building in New York City, which the public quickly redubbed the Flatiron Building because of its iconic triangular plan. All of these buildings followed an architectural model developed in Chicago: a tower structure; a clearly defined base; a straight, vertical shaft that filled the site and rose without interruption; and a distinctive final story to mark the top.

1.12 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, New York and Chicago competed to build ever-taller skyscrapers. In 1903, Daniel Burnham’s Flatiron Building reached twenty-one stories, making it the world’s tallest.

Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Within five years, the forty-one-story Singer Building, designed by Ernest Flagg, had overtaken the Flatiron Building as the tallest in New York. In 1908, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company added to its existing building a fifty-two-story tower designed by Napoleon LeBrun, only to see it surpassed in 1913 by the fifty-five-story Woolworth Building designed by Cass Gilbert.36 The race was on, as captains of the Industrial Revolution and their armies of managers raised lofty new palaces above the laboring city.

1.13 The Singer Building (1908). Provoked by the Flatiron Building’s unvarying massing from pavement to cornice, architect Ernest Flagg argued for setting towers back from the property line at the tenth or fifteenth story. Buildings like the Flatiron, he argued, blocked sunlight and failed to capture the drama of skyscrapers, so he used his own design for the forty-one-story Singer Building as a real-world demonstration. The idea of upper-level setbacks appeared in big-city building codes across the United States in the 1920s and directly inspired New York’s “wedding cake” skyscrapers from the 1920s through the mid-1960s.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Although U.S. cities had rapidly pushed outward, their focus remained their core commercial areas. As land values rose, new technology allowed more density and height, which further increased land values. For millennia, the design and pattern of cities had been horizontal. Now city planners and designers began to think about the vertical, and planned ever-taller buildings that would define streets and public spaces.

Ernest Flagg himself loathed the shadowed streets and stark canyons produced by the burgeoning crop of skyscrapers. Unable to hold back the tide, the Beaux Arts–trained Flagg shifted to reforming skyscraper design. Departing from his own earlier designs, which filled their sites in the same way the Flatiron Building did, Flagg advocated setting back from the property line a tower of ten or more stories so that it would fill only a portion of the building’s footprint. Doing so, he argued, would open all four sides of the tower element to design and view, and that “we should soon have a city of towers instead of a city of dismal ravines.”37 Flagg’s design for the Singer Building helped introduce this model. He rebuilt an 1896 structure to serve as its base, and the resulting Beaux Arts building rose more than 600 feet above Manhattan. Flagg’s approach, which influenced other towers, including the Woolworth Building, impacted later building regulations strongly.

To the horizons: Suburbs

The first industrial-era American suburbs were leafy enclaves for the rich. In these railroad suburbs, managers and owners traded the squalor of industrializing cities for a quiet, clean, and uncrowded setting. The onset of industrialization helped promote a new, idealized view of the outdoors reflected in the large volume of literature and sentiment on the subject that appeared between 1840 and 1860.38 Henry David Thoreau wrote Walden during this period, and an increasing flow of books about suburban cottages and landscaping were published in the emerging architectural press.39 Americans began to yearn for a new Eden in the healthful and wholesome countryside—an idyllic paradise of garden cottages far from the soot and din of the industrial city and, ironically, made possible by the era’s smoky icon, the railroad.

1.14 Upon its completion in 1913, the Woolworth Building in Manhattan became the tallest building in the world, a title it held until the completion of the Chrysler Building in 1930.

Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Upper-class railroad edens

Some early new Edens represented experiments: Llewellyn Park in New Jersey, Riverside outside of Chicago, and Garden City on Long Island. They caught on quickly, however, and railroads soon led to some of America’s most celebrated suburbs, from Chestnut Hill in Massachusetts to Lake Forest and Oak Park in Illinois. Plans for some of these early suburbs emerged from the offices of such influential designers as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, known for New York’s Central Park and other major urban parks across the nation. True to their design roots, Olmsted and Vaux visualized the housing in their new suburbs as “cottages in a park.” Their designs combined generous lot sizes, “English cottage” architecture, and sumptuous landscaping. Their work shaped a new approach to urban design closely allied with the English Romantic landscape school and characterized by winding lanes and picturesque views. This approach became the model for early automotive suburbs and for major interventions in the industrial cities themselves.40

Middle-class “transit” suburbs

Suburbs did not remain a preserve of the rich for long. Complementing the era’s emerging forms of transportation, new building methods encouraged an entirely new kind of development: the streetcar suburb. After the middle of the nineteenth century, a new way of framing buildings—using light wooden members joined by industrially produced nails and screws—began to replace existing, more labor-intensive methods. Within a few decades, this new approach had transformed home-building from an ancient craft into an industrial process; the rapid development of common designs, pattern books, precut kits, and manufactured windows, doors, and molding accelerated the transformation. For the first time, housing could be mass-produced.

The new building technology and electric railways arrived at the right time for skyrocketing urban populations. While early railroad suburbs had established secluded enclaves far from the city, electrified streetcars, subways, and elevated trains spurred dramatic expansions of the cities themselves. Existing grid patterns marched across the landscape, frequently growing in long ribbons of new construction that shot out from the center of a city along new streetcar lines, with land often developed by the transit operators themselves. The width of the band of new development was controlled by walking distance from the rail line as well as the operators’ land acquisitions.41

1.15 West Newton Hill, near Boston. The first American suburbs—leafy enclaves built for the rich and connected to nearby commercial centers by railroads—adopted a romantic design vocabulary of winding streets, cottage-style architecture, lush landscaping, and picturesque views. In a sense, they represented the “anti-grid” and introduced a new approach to urban design in the United States.

Courtesy of Oliver Gillham

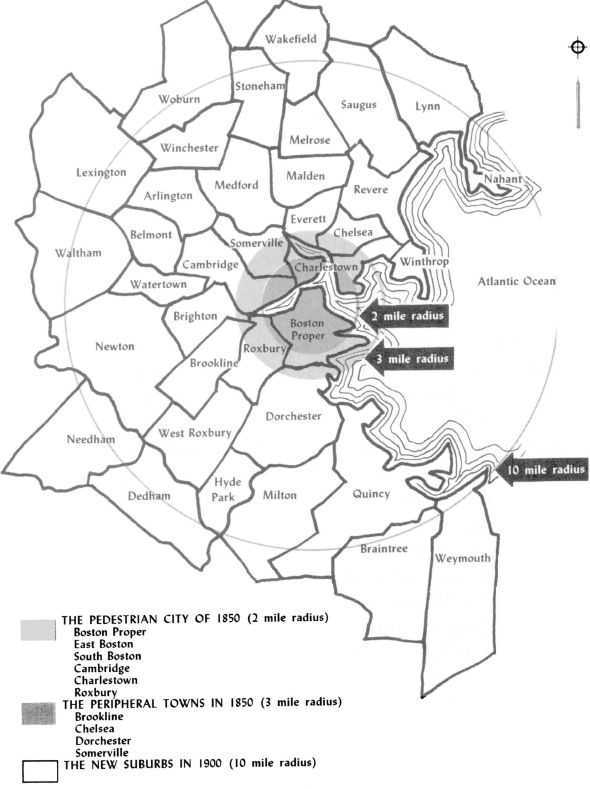

Over time, the ribbons broadened into what are today the older, inner-ring suburbs of many major cities. These include Highland Springs in Richmond; Dorchester and Brighton in Boston; Mount Lebanon in Pittsburgh; Shaker Heights in Cleveland; Hyde Park in Chicago; University City in St. Louis; and similar communities. Electrified transit lines opened up a new urbanized territory that more than tripled the size of many older cities. New York City increased its territory from 27 square miles to more than 300 square miles between 1850 and 1900 (the annexation of Brooklyn accounted for roughly a quarter of this increase). During the same fifty years, the radius of urbanized Boston expanded from 3 to 10 miles, and the land inside Chicago’s city limits mushroomed from 10 to 185 square miles.42 These expansions mostly accommodated the working and middle classes. Electrified transit, combined with wood-frame construction, made land and construction cheap enough for large-scale development. As Kenneth T. Jackson writes, “For the first time in the history of the world, middle-class families in the late nineteenth century could reasonably expect to buy a detached home on an accessible lot in a safe and sanitary environment.”43

Streetcar suburbs created an entirely new type of urbanization in the United States: relatively dense, wooden-framed neighborhoods of one-, two-, and three-family homes on lots as small as a tenth of an acre. High-volume transit lines in places like Brooklyn and the Bronx turned these suburbs into urban neighborhoods in their own right, dense enough to rival any city center. Boston, Chicago, and other cities retained their wooden-frame texture. For all of these communities, a grid layout principally offered a convenient tool for parcellation, development, and land sales. Such pragmatic concerns often crowded out public land uses, including streetscapes, public squares, and parks.

1.16 The growth of Boston’s “streetcar suburbs.” The advent of electrified streetcars and new methods for framing and erecting buildings supported dramatic expansion of U.S. cities in the last half of the nineteenth century. Development followed the inauguration of new transit lines in an early expression of transit-oriented development.

Reprinted by permission of Sam Bass Warner, Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston 1870–1900, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and MIT Press, 1978): 2; © 1962, 1978 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

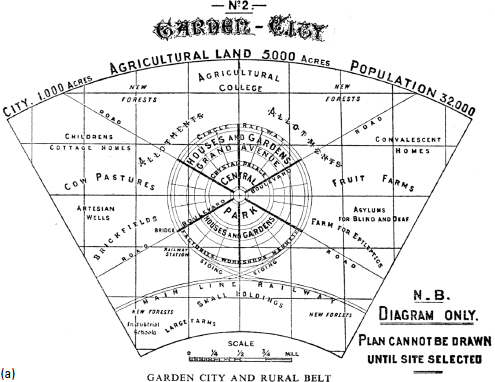

A British refinement: Garden cities

Europeans looked aghast at such American urban patterns, which they saw as the equivalent of late-twentieth-century sprawl. The discontented included Sir Ebenezer Howard, the inspirational planner of England’s greenbelt towns. In his influential book Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902), Howard proposed a compelling alternative to the uncontrolled suburbanization he saw devouring the English countryside. To avoid haphazard expansion of industrial cities, he proposed substituting strings of discrete, mixed-use communities of about 6,000 acres and thirty thousand residents. Each new city would contain its own employment centers, residential neighborhoods, and shopping districts, together with an ample supply of parks and other public open spaces. He proposed surrounding each community with a permanent belt of agricultural land,44 a concept borrowed from the baroque military engineers and from towns like Palmanova.

Howard’s ideas never caught on in America, despite many advocates and more than a century of attempts, but his influence remained powerful. For example, Clarence S. Stein’s Toward New Towns for America proposed a series of regional towns based on Howard’s model. Walt Disney drew on the model, too, in planning Disney World’s Epcot Center. (Built after Disney’s death, the project wandered far from the path Disney had mapped out).45 The greenbelt community concept enjoyed a brief resurgence in the New Town planning movement of the 1960s and ’70s: fragments of Howard’s vision appear in the communities of Columbia, Maryland, and Reston, Virginia. More recently, the New Urbanist and Smart Growth movements have revived some of his ideas.46

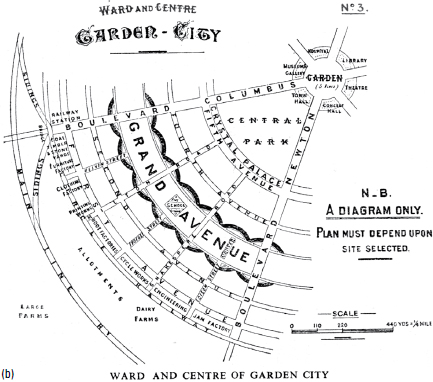

Regulating the industrial city

Early in the industrial age, popular prints presented factories as icons of awe-inspiring beauty. As cities grew more congested and dense, however, such sentiment waned; mixing horizontal and vertical uses felt increasingly like a threat to public health and an assault on aesthetics. Factories and rail yards in particular made bad neighbors in residential districts, smoking and roaring day and night, heedless of their impact on light, clean air, and tranquility. Factory workers lived jammed together in wretched conditions that created serious health and fire hazards. Publication in 1890 of Jacob A. Riis’s photographs in How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York provided graphic documentation of the squalid living conditions that immigrant factory workers endured, inflaming public opinion and joining a swelling chorus of condemnation in the arts, mass-circulation newspapers and magazines, and politics.

In 1916, New York City instituted the first zoning ordinance in the United States, prompted not only by the squalor of industrial slums but also by the encroaching shadows of the skyscrapers that had come to dominate the skyline in just a few years. The new code established specific building and land use districts and spelled out enforceable regulations for building sizes and uses within those districts. Zoning caught on quickly: within ten years, more than 80 percent of U.S. cities had adopted zoning ordinances.47 And financial concerns dovetailed with the public health concerns that drove their adoption. Zoning might bring light and air back to city streets and homes, but it also helped stabilize property values by providing some assurances about what might someday be built next door.48

Zoning formalized the idea of separating land uses into specific districts, or zones, of a city. Confining new factories and rail yards to industrial districts and gathering houses and apartments in residential zones sequestered incompatible uses so that families would no longer have to share Sunday dinner with the drop forge or hat factory next door.

More finely graduated land use combined with enforced low density as zoning evolved, leading critics to blame it for many things, including suburban sprawl. Jane Jacobs also fingered single-use zoning as the culprit that destroyed the vitality of dense, mixed-use cities in The Death and Life of Great American Cities.49 Despite zoning’s flaws and unintended consequences, urban life in the industrial era was undeniably intolerable without it. (Only recently has its application to suburbs and postindustrial cities come into question).50

1.17 a,b Diagram details for a prototypical garden city. British reformer Ebenezer Howard advocated an alternative to relentless expansion of industrial cities: small, self-contained cities surrounded by permanent greenbelts. His vision, which drew on the plan for Palmanova (among other sources), influenced twentieth-century city planning in the United States, from the first car-oriented suburbs to the thinking behind the New Urbanist movement in the 1980s and ’90s.

Courtesy of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA)

1.18 By 1890, community leaders had begun to argue for regulations to control the proliferation of telegraph, telephone, and electrical wires in Manhattan’s streets. The city eventually required their burial, a precursor to broader controls that ultimately produced the country’s first zoning ordinance.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Zoning shaped cities in powerful ways. New York City’s art deco “wedding cake” skyscrapers, for example, owe form to the city’s early zoning, which mandated setbacks on new buildings to allow light to reach the street. Following World War II, many cities adopted zoning that took a different approach—allowing the construction of taller buildings in exchange for the creation of pedestrian plazas—producing a strikingly different effect. With the retreat of buildings to the center of plazas, sidewalks lost both energy and definition, which diminished the appeal of walking.

Bringing beauty and order to the industrial city: The City Beautiful movement

New models of urban intervention emerged in Europe in the middle of the nineteenth century, particularly in Paris, where many influential American architects received their training. In 1853, the French emperor Napoléon III hired Georges Eugène Haussmann to modernize the city with the aim of improving public health by opening streets to light and air and enhancing circulation and safety. Beyond these goals, the emperor had a political agenda—creating streets wide enough to accommodate rapid troop deployment and making it impossible to block streets with barricades, as the revolutionaries of 1848 had done. Haussmann laid a series of broad diagonal boulevards and starlike squares over the tangled Paris street network. In the grand manner of baroque-period planning, his much admired scheme showed little regard for the character of medieval streets.

Haussmann’s revival of baroque-style planning gained a foothold in the United States at the Chicago world’s fair of 1893—formally, the World’s Columbian Exposition. Under the leadership of Daniel Burnham, a team of leading architects and designers that included such luminaries as Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles Follen McKim, and Louis Sullivan designed a vast temporary city to house the exposition. Although covered in flimsy white plaster, the classical architecture of the great Beaux-Arts pavilions along Lake Michigan influenced American city-building for a century. Visitors to the “White City” returned home wondering what might be done to bring light, air, and beauty to their own drab and sooty municipalities. That impulse to brighten, beautify, and improve civic spaces coalesced under the banner of the City Beautiful movement.

Advocates of City Beautiful sought to advance many of the same goals Haussmann had pursued. Motivated by a desire to bring in light and air, the movement also responded, if less overtly, to concerns about growing radicalism among urban industrial workers (a concern memorialized in the profusion of urban armories that sprang up in this period51). The City Beautiful movement also reflected a growing interest in slum clearance among the emerging urban middle class.

The impulse to beautify American cities actually reaches back to the 1840s, when writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne began to romanticize the bucolic countryside.52 In 1853, New York’s legislature set aside more than 800 acres of land for a park in Manhattan, partially at the urging of nationally known landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing. In 1857, the city’s parks commission selected Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to design what would become Central Park.53 Olmsted and Vaux drew inspiration from popular pastoral urban cemeteries like Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but great European parks like London’s Hyde Park and the Bois de Boulogne in Paris were equally influential models.

1.19 Georges Eugène Haussmann’s “modern” boulevards cut through Paris, redefining a medieval city that had grown organically for more than two thousand years into the baroque city we know today.

Courtesy Beth Lieu Song, via Wikimedia

Not everyone applauded City Beautiful interventions, however. Spiro Kostof writes that “common people and cultural critics alike looked with increasing distaste and alarm at the new breed of technocrats . . . who unapologetically gutted historic cores for the sake of circulation. Eventrement, evisceration, was the term popular with the most famous ‘demolition artist’ of the time, Baron Haussmann.”54 In fact, a countermovement arose in Germany headed by followers of Camillo Sitte, whose 1889 book City Planning According to Artistic Principles advocated a more contextual and picturesque approach to street planning.55 Sitte’s followers became dogmatic advocates of curvilinear street patterns, in direct opposition to the more baroque ideas of Haussmann and others.56 Sitte’s ideas and those of his followers eventually influenced American urbanism—particularly the design of suburbs—in profound ways, but Burnham and his team remained devotees of Haussmann’s work.

In the wake of the 1893 fair, Burnham became an active proponent of the City Beautiful approach, devising master plans for Chicago, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Washington, most of which drew in part on Haussmann’s plans for Paris. Burnham’s plan for Chicago included a series of great diagonal avenues piercing the city’s well-known grid and converging on the city’s business district and a new civic center. His concerns were both functional and aesthetic: he believed that diagonals saved time and distributed traffic more evenly but also held beauty. “There is true glory in . . . vistas longer than the eye can reach,” he wrote.57

1.20 World’s Columbian Exposition (1893). The temporary pavilions at the Chicago World’s Fair influenced American city-building for a century—most directly through a revival of interest in classical architectural vocabulary for civic buildings, but more broadly through the City Beautiful movement, which promoted large-scale gestures to improve the appearance of American cities.

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Few of Burnham’s plans were ever fully realized, in part because only an authoritarian patron could make his sweeping recommendations possible. France, with a highly centralized government headed by an emperor, differed markedly from the republican United States, with its stubbornly independent city, state, and federal jurisdictions. Kostof describes the problem:

The City Beautiful movement left America’s cities with significant and treasured, if often fragmentary, improvements. Planning inspired by the movement continued into the 1930s and included such iconic works as the National Mall in Washington, D.C.; great parkways like the Merritt in Connecticut; Charles Eliot’s parks along the Charles River in Boston; the Chicago lakefront; Kansas City’s parks and parkway system; the Denver and San Francisco civic centers; and even many early works masterminded by New York City redevelopment czar Robert Moses, such as Jones Beach and Riverside Park. Moses, in fact, came closer than any other American to achieving the authoritarian status needed to carry out a sweeping City Beautiful plan. By shrewdly playing state and local politics and by winning appointment to key public infrastructure posts, he transformed the New York region with bridges, highways, parks, and recreation centers over a forty-year period. His planning almost invariably assumed wiping parcels clean of existing urban fabric; the resulting destruction of vast swaths of traditional neighborhoods symbolized popular attitudes toward American cities for much of the twentieth century.

1.21 A grand city hall and plaza stood at the “center of a system of arteries of circulation” around which architect Daniel H. Burnham organized his plan of Chicago in 1909. A nationally influential leader of the City Beautiful movement, Burnham made only passing reference to the emerging concept of zoning, instead proposing a baroque framework of grand boulevards and public spaces intended to give Chicago a new sense of grandeur. This same aesthetic informed plans Burnham drew up for Cleveland, San Francisco, and other cities. Only Washington, however, with its grand L’Enfant layout, fully embraced his recommendations, contained in the MacMillan Commission report of 1901.

Jules Guerin rendering from Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago (Chicago: The Commercial Club, 1909).

In the pursuit of the curvilinear and the picturesque, some City Beautiful projects reflected the ideas of Sitte and his followers more than those of Haussmann and Burnham. But all shared a romanticized view of cities that looked back to an imagined preindustrial era of grand, even aristocratic European cities.