Chapter 2

Decentralization: The Rise and Decline of Industrial Cities

World War I, the world’s first fully industrialized war, swept away the romanticized picture of historic European cities and reshaped society around the globe. Europe went to war in 1914 on horseback but emerged from it in motorized vehicles. Aftershocks rumbled through every field of human activity—including architecture and city planning—and the war accelerated the pace of life, broadened the impact of industrial production, and provoked widespread social activism. In Europe, radical ideas about the rebuilding and redesign of cities broke from a familiar Renaissance-derived aesthetic and practice to proffer a vision of a world reborn through technology and progressive political ideas, the manifestation of which became known collectively as the International Style. In the United States these impulses took a very different path, one cleared by scouts as unalike as General Motors and Frank Lloyd Wright and leading not to the hearts of cities but to their leafy green edges: the suburbs.

Proto-Urban Design: Rejecting a Classical Past to Shape an Industrial Future

Europe: Modernizing the past

L’Esprit nouveau

Surrounded by the devastation of the war, the world looked to the future. The 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts) in Paris, a seminal global showcase, launched the streamlined art deco motifs that became widely popular in the 1930s in Europe and the Americas. At the Expo, one modest pavilion—designed by an obscure architect and located in an out-of-the-way part of the fairgrounds—caused an outsize sensation. Its Swiss-born architect, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, had adopted the pseudonym Le Corbusier, meaning “the crow-like one”; his Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau (Pavilion of the New Spirit), a stripped-down, rigidly geometrical box devoid of any ornamentation, endorsed austerity rather than exuberance in housing design. Paintings by Fernand Léger and by Jeanneret himself of geometric forms and colors inspired by machines hung above Michael Thonet bentwood furniture. Le Corbusier banished art deco entirely in a “machine for living” stripped of frivolous decoration.1

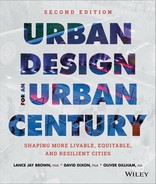

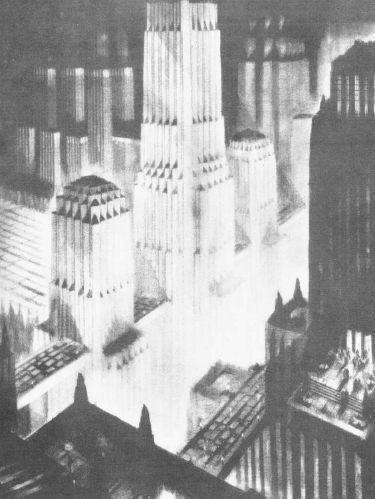

Even more startling was a glass-encased diorama in the pavilion holding a model of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris. Named for the automobile company that had helped finance the pavilion, the plan proposed razing almost the entire historic city north of the River Seine. In its place would rise sixty-story glass office towers arrayed in grid formation, each centered on a vast highway interchange and 800 feet from its nearest neighbor. Open parkland and superhighways filled the vast voids between the towers, and titanic linear apartment blocks zigzagged across the landscape, filled with apartments that look like the model in the pavilion.2 Compared with intervention on this scale, Haussmann’s plans (see chap. 1) seemed tame. The diorama so horrified exhibition authorities and the French architectural establishment that they tried, unsuccessfully, to have it fenced off. Instead, it would have won an award from an international jury had the French not vetoed the prize.

The plan traced its roots to 1922 and the Salon d’Automne, where Le Corbusier had unveiled La Ville Contemporaine, a modern conceptual city for three million people. As in the Plan Voisin, sixty-story cruciform glass-and-steel skyscrapers formed its main office district. These skyscrapers, containing both the offices and apartments of elite industrialists, sat within large parks framed by the same zigzagging proletarian housing blocks in the Plan Voisin. The plan separated vehicular roadways and pedestrian pathways throughout; at the city’s center stood a multilevel transportation center that accommodated buses, trains, a highway interchange, and a landing strip for aircraft on the roof.3 Le Corbusier, writes biographer Robert Furneaux Jordan, believed that “the tall building must at all costs be a liberating thing . . . to release land for other purposes: recreation, foliage, lakes, schools, crèches, theaters, restaurants, highways, and so on.”4

2.1 Plan Voisin (1925). Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, scandalized the French architectural establishment with his plan for razing a large swath of central Paris in order to build massive office towers and apartment buildings set in vast parks and connected by superhighways. His plan reflected an approach that dominated modernist architectural thinking in Europe during the 1920s and ultimately shaped American thinking about urban renewal in the 1940s and ’50s.

© Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris, FLC

The workers’ city

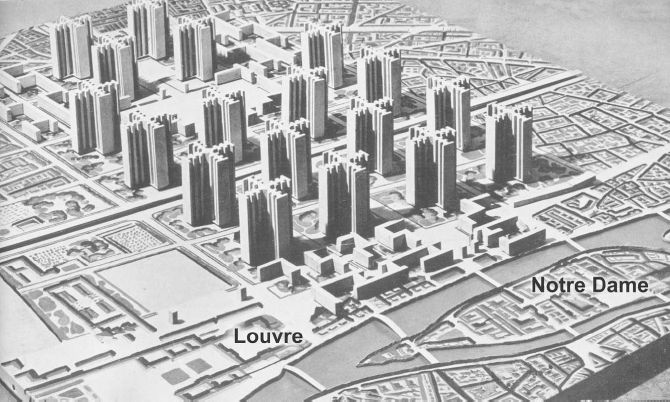

Other widely known plans embraced a new, industrial aesthetic. Tony Garnier’s 1917 plan for Cité industrielle, for example, based on work he’d begun as an architecture student, represented an idealized socialist city designed in reaction to the dehumanizing conditions in which millions of urban residents lived, most of them first-generation urbanites whose families had fled rural poverty. Its utopian agenda in some ways wielded far more influence than Le Corbusier’s plans.

Garnier set his city of 35,000 inhabitants on a river in southern France. In size it roughly matched Ebenezer Howard’s garden cities, which may have provided inspiration. Garnier, however, pushed well beyond Howard’s ideas. Anticipating future planners by decades, Garnier zoned his city rigorously, separating the industrial quarter from residential neighborhoods and public zones that contained cultural, health, and governmental facilities. In a likely bow to Camillo Sitte, the Cité Industrielle preserved and incorporated a medieval town within its borders, and Garnier’s Beaux-Arts training revealed itself in the plan and its monumental civic buildings. But his housing prototypes showed the industrial severity of emergent modernism. “It was above all a socialist city,” Kenneth Frampton writes in Modern Architecture: A Critical History, “without walls or private property, without church or barracks, without police station or law courts; a city where all the unbuilt surface was public parkland.”5 Garnier’s work inspired many plans that emerged after World War I.

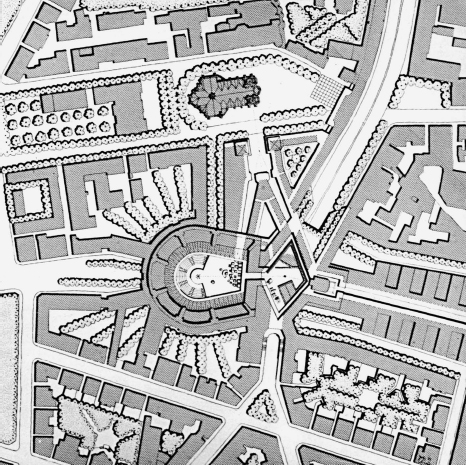

2.2 Cité industrielle (published 1917). Tony Garnier’s plan for an idealized socialist city in France influenced many early-twentieth-century urban plans. It blended emerging modernist ideas (zoning and industrial production of housing) with more traditional influences—and even historic preservation.

Reprinted with permission from Tony Garnier, Une Cité Industrielle: Étude pour la Construction des Villes (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1989).

In the late 1920s, Le Corbusier intended his machine-inspired modern forms to convey a similar break with an elitist past and herald an era of cities shaped to enhance the lives of the industrial working class. The modern idiom clearly expressed Le Corbusier’s social goals to European contemporaries, and the concept of integrating form and social justice quickly spread across industrialized Europe. Germany’s Staatliches Bauhaus design academy emerged as a continental headquarters of modernist design during this decade, first under director Walter Gropius and later under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. (Together with a third faculty member, Marcel Breuer, they would influence twentieth-century architecture and urban design tremendously.) Radical ideas also bubbled out of what had become the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) after the war. Konstantin Melnikov’s Soviet Pavilion and annex represented the Vkhutemas—the Soviet equivalent of the Bauhaus—at the seminal 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne in Paris.6 It offered a stunning representation of the emerging wave of revolutionary architecture and urbanism based on industry.

Throughout the 1920s, the major political battles in Europe—particularly between Marxism and its opponents—resounded in the world of architecture. Socialists saw industry as a means for achieving socialist revolution; opponents, like Gabriel Voisin, sponsor of the Plan Voisin, saw it as the province of elite capitalists.7 Le Corbusier embraced capitalism and sorted housing by class in his Ville Contemporaine. The Soviets, in contrast, aimed for a classless model,8 a new kind of city that strove to express “the disappearance of the contrasts between center and periphery, between fashionable districts and workers’ slums, and even, in the last analysis, between city and country.”9 Imbued with idealism and revolutionary fervor, Soviet architects drew up bold plans for linear cities and crisp, clean housing blocks in parklike settings with plenty of space, air, and light—all things that the City Beautiful movement had promoted in the United States, but with a drastic revolutionary and industrial twist.

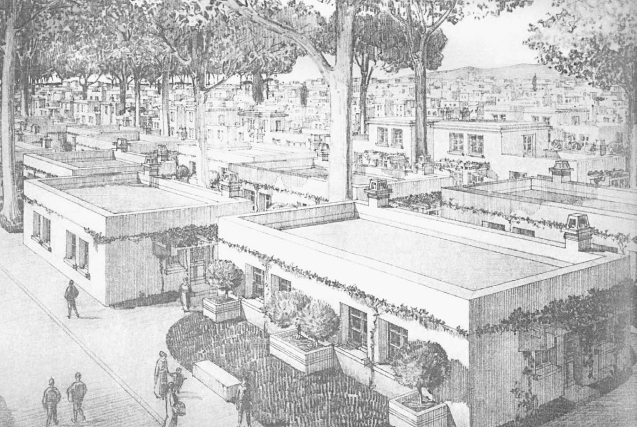

Even in revolutionary Russia, conflicting schools of thought had emerged. The so-called urbanists pushed the communal aspect of the city to the maximum. They proposed housing projects with only 5 square meters (roughly 55 square feet) of private space for each occupant, allocating everything else—bathrooms, kitchens, living areas, outdoor space—to the common realm.10 Another group, the so-called disurbanists, stressed dispersed settlements of detached dwellings organized along transit lines. And Russia, at least for a brief period, actually strove to realize some of these plans, mostly along disurbanist lines, in industrial cities built from scratch, like Magnitogorsk.11

2.3 Communal House by Barsch and Vladimirov (1930). Revolutionary thinking upended traditional approaches to urban planning in Europe after World War I. In the Soviet Union, one school of thinking argued for communal housing that allotted each occupant roughly 55 square feet of personal space, with everything else used and held in common.

From the journal SA (1930); courtesy of Creative Commons.

Despite their differences, architects from different countries strove to bring the world a new international style of architecture that adopted the vocabulary of industrial buildings and found aesthetic inspiration in the newly discovered possibilities of steel-reinforced concrete and an aversion to ornamentation. If housing would become a machine for living, office buildings, too, should lose superfluous detailing; giant towers with walls of glittering glass translated the industrial revolution directly into built form. Planning efforts described revolutionary new cities that embraced industry as its muse while mitigating its impacts with rigorous zoning, better housing for workers, and broad, parklike settings with light and air. It was a logical step for these architects to create an organization for debating, codifying, and executing their ideas.

America: Reaching for the future

Towers come of age

Skyscrapers evolved from their beginnings in the 1880s to their quintessential American form in the 1920s. In New York—which in 1939 boasted more tall structures than any other city in the world—the art deco shapes of the Chrysler and Empire State buildings defined the skyline, buttressed by a host of other elegant towers bearing the names of corporate owners like American Radiator, the New York Daily News, the Cities Service Company, Irving Trust, and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Although art deco had originated in Europe, the United States embraced the style enthusiastically and applied it to architecture on a grand scale.

The masterwork of the era, Rockefeller Center, neared completion in 1939. Begun in 1930, the complex comprised fourteen towers designed by Raymond Hood, all clad in Indiana limestone and sliced by vertical stripes of glass and bronze. In many ways Rockefeller Center represents the archetypal work of purely American urban design. Covering three city blocks, its centerpiece is a below-grade plaza with a heroic-scale statue of Prometheus bringing fire to man. Behind the sculpture rises the knifelike edge of the seventy-story RCA (now General Electric) Building, with Zeus wielding a lightning bolt above its entrance. Everything about the complex celebrated twentieth-century industrial modernity, from the towers themselves, with their decorative arts and sculpture celebrating man and industry, to its nickname, Radio City. Sublevel walkways connect all fourteen towers, the city’s subway system, and a pedestrian concourse lined by shops and restaurants that range around the sunken plaza. This multilevel circulation system prefigured postwar urban design thinking.

Architectural illustrator Hugh Ferriss idealized the style of Hood and his contemporaries, projecting them onto an imaginary cityscape in his book The Metropolis of Tomorrow.12 His dramatic, bottom-lit aerial perspectives of an archetypal art deco city, with ziggurat-topped towers rising into the night, celebrated a purely American, high-density urbanism. Ferriss’s renderings symbolized the age, and by the 1940s such art deco skyscrapers dominated the skylines of American cities as varied as Pittsburgh, Miami, Tulsa, Houston, and Seattle. Boston’s John Hancock Building, Detroit’s Guardian Building, Chicago’s Board of Trade Building, and the city halls of Buffalo and Los Angeles are especially well-known emblems of the period.

Magic motorways

The year 1939 marked a watershed in American urbanism. The United States had reached the pinnacle of its distinct brand of vertical city-building: the skyscraper was king, and the urban center was its kingdom. The supremely art deco Trylon and Perisphere dominated the world’s fair that opened in New York that year, both reflecting its time and hinting at changes to come.

2.4 Rockefeller Center, New York (1929–39). Perhaps the crowning achievement of American urban design in the skyscraper era, Rockefeller Center’s design celebrated industrial modernity. Among its pioneering features, a web of subterranean walkways connects the complex’s fourteen towers and suggest the separated levels of circulation that distinguish many plans in the urban renewal era.

Courtesy David Shankbone, via Wikimedia.org

2.5 Rendering from The Metropolis of Tomorrow. Hugh Ferriss’s distinctive style of architectural rendering helped idealize the massing of New York skyscrapers (itself a product of the city’s 1920s zoning code) and transform the skyscrapers into models that influenced the shape of urban buildings across the United States for decades.

Reprinted by permission from Hugh Ferriss, “Crowding Towers,” in The Metropolis of Tomorrow (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 2005), 63.

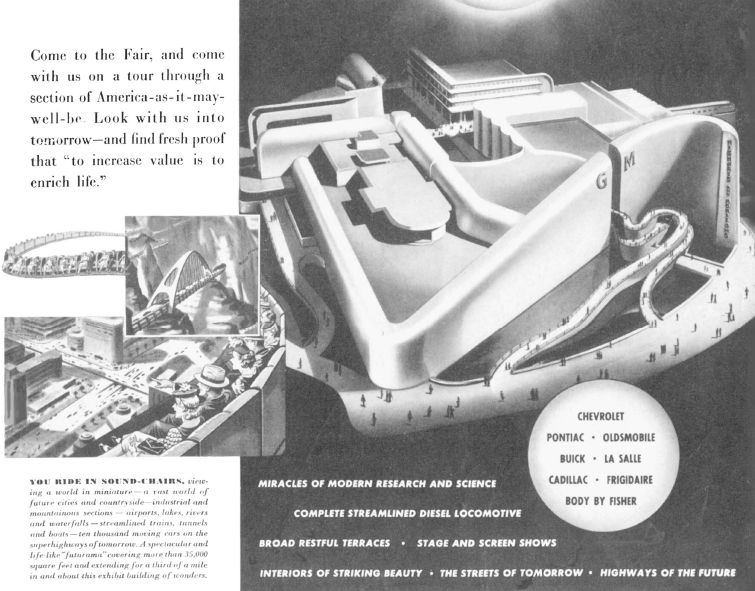

If Hugh Ferriss’s renderings celebrated height and density, the pavilions at the fair (1939–40) proved a more accurate forecast of the future of American urbanism. More than five million people climbed the great serpentine ramps leading to the General Motors (GM) pavilion, the most popular at the fair. Conceived by prominent industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes, the Futurama exhibit provided displays and models of future cities served by high-speed, limited-access continental highways. In stunning dioramas, expressways with looping ramps snaked across the countryside. In The World of 1960, these “magic motorways” sped commuting fathers home to the suburbs at 100 miles per hour. To accommodate an anticipated flood of new cars (the pavilion sponsor did, after all, make them), GM and Bel Geddes redesigned cities, placing vehicles and pedestrians on different levels. Although hardly a new idea—Leonardo da Vinci devised a fifteenth-century plan for Milan that placed service tunnels and canals belowgrade, reserving surface streets for pedestrians—such plans had gone unrealized. Eugène Hénard’s 1910 Street of the Future and other plans for Paris were built around similar ideas;13 World’s Fair patrons could see its realization in Rockefeller Center’s below-grade pedestrian concourse.

General Motors’ dramatic vision of grade-separated cities influenced much urban design in the second half of the twentieth century, even though most city streets in the United States remain single-level today. The pavilion’s real vision lay in its idea of the open landscape. In Metropolis of Tomorrow, Ferriss had posited a vertical urban future; Futurama unveiled an entirely different vision—a horizontal city rarely rising above three stories and spreading from horizon to horizon. Two decades after the 1939 fair, the United States would build a vast continental infrastructure that formed the underpinnings of a nationwide suburban metropolis.

2.6 Advertisement for the General Motors (GM) pavilion at the New York World’s Fair (1939–40). Among the marvels that GM’s popular Futurama exhibit predicted included a vast, automobile-oriented suburbia served by a network of superhighways. Within twenty years, the United States was busily concretizing a very similar vision.

Advertisement from the New York Times, March 5, 1939

In fact, GM’s auto-dominated future had already begun taking shape by 1939. An invention of the late nineteenth century, the automobile began as a plaything of the wealthy; by 1900, the United States had a modest supply of just eight thousand.14 As manufacturing costs fell and as governments at all levels enlarged the network of paved roads, automobile ownership burgeoned. By 1927, Americans were driving twenty-six million cars, an increase of well over 3,000 percent in less than three decades. The car was on its way from upper-crust toy to middle-class necessity.15 By 1939, a national highway system was already in place, comprising primarily two- and four-lane arterial roads with traffic lights, roadside retail, and multiple curb cuts. The numbered roads in the national system began with Route 1 on the East Coast and ended with Route 101 on the West.

By the 1930s, parkways had appeared near New York, Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and other cities. Often grade-separated and with minimal curb cuts, these roads for “pleasure vehicles” formed part of park systems or provided access to parks well beyond the city. Carefully landscaped, they incorporated picturesque overpasses that carried intersecting roads to provide for a scenic—and minimally interrupted—ride. Although intended as routes to recreation for city dwellers, parkways turned out to be convenient for commuting from the suburbs as well. Originally treated as civic improvements built for recreation, their function quickly shifted to utilitarian commuter routes.16

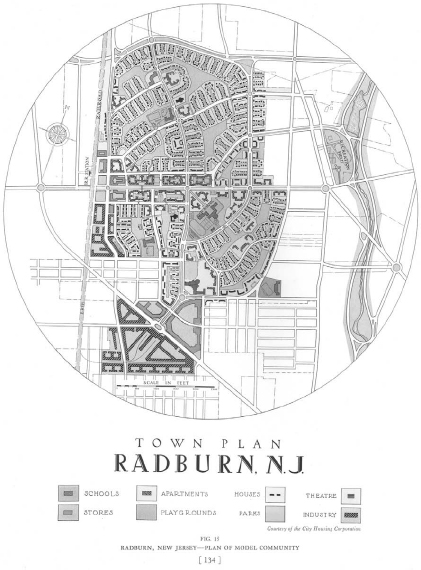

Automobile suburbs for Everyman

As early as the 1920s, with a national highway system and new parkways under construction, U.S. cities began to see their first automotive suburbs. Radburn, a community within the town of Fairlawn, New Jersey, gained a national reputation from its 1927 launch as one of the first “towns for the motor age,”17 with a layout prototypical of suburbs to come. Street sizes matched the traffic volumes they were intended to support, with large arterial streets carrying the heaviest traffic outside the community and roads through residential neighborhoods narrowing until they reached cul-de-sacs that each served a cluster of individual residences. The entrances to individual houses turned away from the street to face private gardens, which in turn provided access to pedestrian greenways that ran behind the houses and crossed streets on overpasses and underpasses. Many of Radburn’s innovations became standard suburban features, although the greenway system survived in only the wealthiest or most self-consciously visionary developments.18

Radburn led a wave of similar developments. During the 1920s, the suburban population of America’s ninety-six largest cities grew at double the rate of their center cities. The populations in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, and Elmwood Park, Illinois, exploded by more than 700 percent. The population of New York’s Nassau County on Long Island tripled during the period, and Los Angeles added more than 3,200 subdivisions with a total of almost 250,000 homes. Much of Kansas City’s Country Club District dates from the 1920s, as do significant portions of Philadelphia’s Main Line. Rail and streetcar service linked some of these new suburbs with downtowns, but it was the automobile that made most of them possible. As early as 1922, almost 135,000 homes in sixty cities could be reached only by automobile.19

The new pattern broke from anything that had preceded it. Walking distance to a fixed transit line no longer constrained new developments. Consequently, untouched land between rail and streetcar corridors began to fill up. While streetcar suburbs had been relatively dense—thanks to limits imposed by comfortable walking distances and land prices—automotive subdivisions spread out as increasing access made walking immaterial and lowered the cost of buildable land by greatly enlarging the supply. The size of an average house lot nearly doubled, while residential densities dropped by half. Garage doors began to replace front porches as house fronts faced away from the street.20

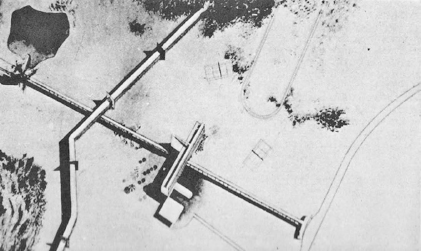

2.7 Plan for Radburn, New Jersey. Automobile registration surged in the 1920s, Radburn became one of the first communities whose design presumed car ownership. Many of its features—including a hierarchy of streets geared to handling auto traffic, cul-de-sacs, and houses facing away from the street and toward private backyards—became staples of suburban planning in the years after World War II.

Courtesy of the Regional Plan Association

Broadacre City

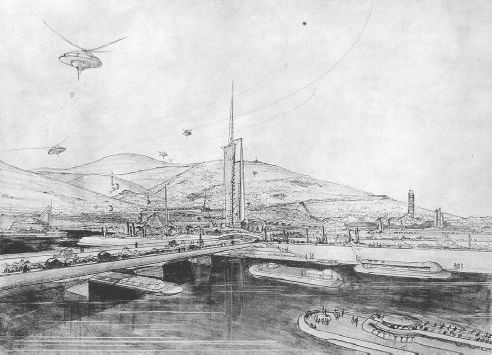

In 1932, architect Frank Lloyd Wright published The Disappearing City, in which he argued that the future lay in suburban metropolises. By 1939 he had formulated a large-scale model of his vision, Broadacre City, a prototype he continued to refine for two decades and described more fully in his 1958 book The Living City. He saw dense city centers as dead ends dominated by machines, gasping for air, and shadowed by skyscrapers. Wright minced no words: “The city, as we know it today, is to die.”21 In its place he envisioned a centerless, horizontal city connected by automobiles and advanced telecommunications. “Natural horizontality,” he wrote, “is the true line of human freedom on earth.” Condemning works like Ferriss’s Metropolis of Tomorrow as “sterile urban verticality,” he argued that dense American cities were, in truth, no more than “pig-pilings” unfit for humans.22 Broadacre City would unfurl across the countryside a carpet of single-family homes, apartments, and office and industrial parks stretching beyond the horizon. In Wright’s vision, the houses would be interspersed with farms and forests held “in trust for future generations.”23

Wright strongly believed that this new city would embody the ultimate expression of Jeffersonian democracy. Decentralization, he felt, was the only way to guarantee individual freedom, and the nascent highway system would deliver that vision. “The great highways are in the process of becoming the decentralized metropolis,” he wrote.24 Wittingly or otherwise, Wright’s vision matched GM’s—and both came close to describing the America’s postwar urban future.

International urbanism: CIAM and the birth of urban design

Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne

In the three decades after its founding, and particularly after 1945, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (International Congress of Modern Architecture, known by its French acronym CIAM) became a significant force in shaping cities in Europe and North America.25 Le Corbusier and his colleague Sigfried Giedion organized the first congress (CIAM 1) and issued a selective set of invitations to avant-garde architects across Europe.26 Urbanism figured prominently in the CIAM 1 agenda. According to Eric Mumford, author of The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960, Le Corbusier used the conference to restate “the ideas of his Plan Voisin in emphasizing the need for urban ‘surgery’ to reorganize existing cities.” He also “asserted the importance of building at very high densities in the centers of cities while still allowing the maximum of space for greenery and transportation routes.”27 In the end, leftist members, shunning skyscrapers as “the last cry of capitalism,” prevented the congress from endorsing these ideas. The congress did, however, support two concepts advocated by Le Corbusier: centralized land planning and the “functional city,” made possible by zoning that separated land uses by function.28

2.8 Perspective of Broadacre City. Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1939 vision for low-rise, decentralized development matched GM’s Futurama ideal. Both predicted America’s devotion to suburban development in the post–World War II era.

Courtesy Flickr user Kjell Olsen, via Wikimedia.org

Europe: The idea of the functional city

Although the rise of totalitarianism in Russia and Germany had muted some voices on the left by 1933, Le Corbusier moved toward that end of the political spectrum in the wake of his involvement in a Soviet competition to plan and design a socialist garden city for 100,000 people. He modified his commentary on the competition into his plan for the Ville Radieuse, or Radiant City, which he presented at CIAM 3 in Brussels in 1930. The Ville Radieuse plan at once affirmed and expanded planning ideas embodied in the Ville Contemporaine and the Plan Voisin, and it significantly influenced CIAM thinking and debate. Meanwhile, Germany’s Walter Gropius had begun to side with Le Corbusier on the subject of tall buildings following a period of sustained opposition to them by German leftists, some of whom maintained their antagonism. In the same spirit of repudiating familiar city forms as a way of rejecting oppressive social systems, Gropius, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and other Bauhaus theorists began exploring concepts for decentralizing cities.

Organizers planned to hold CIAM 4 in Moscow, but the Russian political climate forced it onto a cruise ship sailing from Marseilles to Athens. Focused on the functional city, CIAM 4 (1933) produced little agreement and no formal resolutions, but it did spin off a series of constatations, or observations. Edited by Giedion and Le Corbusier, these documents became the defining text for CIAM’s urbanism, and Le Corbusier incorporated them into his Athens Charter, published in 1943. Josep Lluís Sert—a new supporter of Le Corbusier’s ideas from CIAM’s Spanish contingent—used the constatations as the fodder for his Can Our Cities Survive?,29 which appeared in the United States in 1942, shortly after Giedion’s seminal Space, Time, and Architecture (1941).30 By this point, Gropius, Giedion, and Sert had all relocated to the United States. All three ended up in key positions at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, from whence they spread their ideas, and those of Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter, throughout North America.

The Athens Charter, ostensibly shaped by CIAM’s membership, actually reflected the thinking of Le Corbusier, Giedion and Sert. The document showed the strong influence of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, his earlier Ville Contemporaine and Plan Voisin, and Gropius’s 1920s housing plans for various German cities.31

CIAM leaders come to the United States

Together, the Athens Charter, Can Our Cities Survive?, and Space, Time, and Architecture amplified the influence of European modernist doctrine in the United States after World War II. The planning ideas these architects advocated dominated American urbanism well into the 1970s and have recently enjoyed a revival. For example, the contemporary Landscape Urbanists (discussed in chapter 5) point to Lafayette Park—a utopian redevelopment of Detroit’s Black Bottom “slum” neighborhood developed in 1946—as a “city in the park” model, a useful template for contemporary urban development.

Under the banner of CIAM, Le Corbusier, Giedion, Sert, Gropius, and their American followers advanced a series of urban planning and design principles. First, they posited that cities could be rationally analyzed and described by four functions: dwelling, work, leisure, and circulation.32 Although not entirely original, this functional-city idea established the foundation for the rest of their thinking.

2.9 Detroit’s Lafayette Park, planned and designed by Mies Van der Rohe, replaced a slum with a mix of towers and town-houses set in a landscaped park. Today Lafayette Park is a neighborhood of choice for professionals who want to live close to downtown.

Christian Unverzagt photo courtesy OpenBuildings.org

A second principle excoriated the creeping sprawl of U.S. and European cities and condemned Wright’s Broadacre City concept. They endorsed instead the preservation of the natural environment from what Le Corbusier described as the “leprous suburbs.”33 The solution, they insisted, lay either in wholly new cities, such as those envisioned by Le Corbusier, or in “heroic measures” that would transform existing cities. “The first thing to do,” Giedion argued, “is to abolish the rue corridor with its rigid lines of buildings and its intermingling of traffic, pedestrians, and residences.” In other words, the traditional city with blocks of street-defining buildings would have to yield to something new. He echoed Le Corbusier’s feeling that the existing urban street was “no more than a trench, a deep cleft, a narrow passage. . . . Our hearts are always oppressed by the constriction of its enclosing walls.”34 Le Corbusier himself put the idea even more bluntly that same year: “The present idea of the street must be abolished: death to the street!”

Highways—or parkways, as Giedion called them—would be the new urban corridors, and pedestrians, residences, and vehicles would be clearly separated.35 Tall buildings containing homes and offices would stand apart from one another to allow sunlight and air to circulate through parklike surroundings. “In order to achieve the placement of living quarters amidst greenery in densely populated districts, which is imperative,” Giedion wrote, “there must be a concentration of groups of high buildings standing in parks or, at any rate, in open spaces. Only by such means can the distances necessary for light and air between buildings be secured.”36 (Despite his noble intent, substituting “open spaces” for parks left the door ajar for parking lots to become the open space of choice in subsequent decades.) This ideal was the apotheosis of key goals of the City Beautiful movement and the move toward zoning that had dominated urban design in the first decades of the twentieth century: maximizing light, air, and green space within the city and providing new means of transportation. The automobile would offer the primary means of circulation and govern the layout of future cities—just as GM had forecast.

The theories of English architects Peter Smithson and Allison Smithson took these ideals a step further. They advocated separating pedestrians from the baleful impacts of traffic and proposed putting them on actual pedestals—elevated circulation networks separated from roadways for cars. Their thinking broadly influenced American urban renewal.

Under their third principle, these architects chose government as the primary mover behind “heroic change.” CIAM had endured a long debate over the impediment of private land ownership, but most members ultimately agreed on the need for eminent domain to uproot antiquated city patterns to carry out the necessary changes—a position that paved the way for the midcentury urban renewal movement.

The “anti-industrial city”: Towers in a park

In 1933, at CIAM 3 in Brussels, Le Corbusier had argued that his towers-in-a-park concept would make residents safer from aerial bombardment and gas attack in war.37 This assertion—made at a time when memories of World War I were still fresh—resonated again during the Cold War. By 1951, some U.S. planners argued that traditional, dense cities posed a serious risk in the event of atomic attack. In the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the chairman of Harvard’s Department of Regional Planning, William L. C. Wheaton, called for a national policy of dispersing urban centers. In his article “Federal Action Toward a National Dispersal Policy,” Wheaton recommended “that new construction and urban redevelopment in existing major metropolitan areas be utilized to reduce congestion and excessive concentrations of industry or population.” He went on to praise the “programs of urban redevelopment and slum clearance” carried out under the Federal Housing Act of 1949, which had already begun flattening dense blocks in cities across the United States.38 The same issue of the Bulletin—devoted entirely to dispersion as a national civil defense policy—included an article by a former commissioner of planning for New York City, Goodhue Livingston Jr., recommending the creation of urban firebreaks. “Such firebreaks,” he wrote, “carved out through presently crowded industrial and residential areas, if used as vehicular express highways . . . will afford a means of escape for thousands who otherwise will be burned or suffocated to death.”39

It was not only planners who recommended dispersion and decongestion of the United States’ urban centers; the newly created federal Civil Defense Agency actively encouraged dispersal of industry and employment with financial incentives for new plant construction. The National Security Resources Board also produced literature recommending dispersal with such titles as Is Your Plant a Target?, some of which carried lurid pictures of atomic blasts. Civil defense considerations such as these, in fact, ultimately helped win passage in 1956 of long-stalled legislation to fund the interstate highway system. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 opened the floodgates for what was already a steady stream of migrants to the suburbs in the United States, the dream of GM’s Futurama and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City.

Civil defense considerations, along with the increasing blight in U.S. cities resulting from their depopulation, left municipal officials receptive to the recommendations of Le Corbusier, Giedion, Sert, Gropius, and their followers. Yet despite a prevailing emphasis on dispersion, Le Corbusier and his American followers believed strongly in the survival of the city—but only if completely reinvented using Giedion’s “heroic measures.” The city, Giedion insisted, “cannot continue to exist in its present form.” It “must be transformed but need not be destroyed.”40

2.10 In 1956, Lúcio Costa won an international competition to design Brasília, Brazil’s built-from-scratch capital city, with a proposal inspired by Le Corbusier’s towers-in-a-park model. Intended to contain 400,000 people by the year 2000, the city had actually surpassed 2 million residents by that date. Costa embraced a modernist rejection of “archaic” city qualities, and his plan illustrates some of the most cherished goals of CIAM, including “rational” separation of uses (districts for residential, office, government, hotel, and others) and the use of arterial roadways to separate them. Although Costa’s plan guided only the development of the city center, Brasília stands as the most prominent citywide application of modernist principles. Architect Oscar Niemeyer designed most of the government buildings, including those for the supreme court, presidential offices, and the congress (pictured). Landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx designed the landscapes.

Courtesy Eurico Zimbres, via Wikimedia

Interstate highways abetted this transformation. Construction of the new roadways broke through existing cities, sometimes cutting straight across crowded residential and commercial areas. Supporters used civil defense concerns to justify this destruction, but the perceived need to modernize older cities in order to compete with a rapidly emerging suburban economy drove these projects forward as well. The new urban unit would be the “superblock,” a fusion of multiple city blocks bounded by modern arterial roads and highways. These “urban corridors” would accommodate cars only, with pedestrians relegated to an independent system outside the corridor. And new zoning reinforced such federal urban renewal and highway programs.

Modernism soon dominated in neighborhoods and commercial districts razed and rebuilt according to principles laid down by Le Corbusier and his colleagues thirty years earlier. New York City replaced the setback zoning that had defined the art-deco city. The new zoning allowed developers to build taller buildings in exchange for creating ground-level open space, a change that transformed the Midtown blocks of Sixth Avenue (renamed Avenue of the Americas) into a parade of broad, open plazas nearly devoid of activity, with slablike towers at their center, separated from sidewalk, street, and neighbor.41

2.11 Slablike office towers along New York’s Sixth Avenue set behind plazas devoid of active programming or dedicated use beyond ornamental landscaping exemplify the influence of Le Corbusier and CIAM on American cities.

The post–World War II industrial city

Urban design emerges

The profession of urban design was born into this climate. The followers of CIAM in the United States had for some time believed that there was no borderline between architecture and city planning and that the architect’s ultimate client was society. Le Corbusier and other members of CIAM had arrived at the idea of the “architect-planner” who could “orchestrate” urbanism as early as the 1930s.42 As their U.S. followers’ stature increased, they further developed that concept. In Space, Time, and Architecture, Giedion talks of the “town planner” who must think in more than two dimensions.43 Sert uses the same phrasing in Can Our Cities Survive?44 Yet as city and regional planning gained widespread recognition as a distinct profession, Sert, Giedion, and their colleagues felt the need for something else, neither strictly architecture nor city planning but some combination of the two that could bring about the “heroic measures” necessary to salvage the nation’s cities.

In 1953, Sert—by then the president of CIAM and dean of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design—delivered a lecture entitled “Urban Design” at a conference of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in Washington.45 This is the first widely known instance of the use of that term in an architectural forum. At that conference and subsequently, Sert advocated the “carrying out of large civic complexes; the integration of city-planning, architecture, and landscape architecture; [and] the building of a complete environment” in urban core areas.46 Sert’s evocation of a complete environment built on an idea he’d suggested nine years earlier in “The Human Scale in City Planning,” an essay in which he argued for countering the American trend toward suburbanization by replanning metropolitan regions based on walkable “neighborhood units” focused on schools and other public facilities.47 His idea’s importance, as Eric Mumford later wrote, is that Sert “began to advocate the cultural and political value of urban pedestrian life . . . right at the moment when many businesses and the federal government saw the movement of the white middle class to the suburbs as both desirable and inevitable. Out of this combination of the earlier CIAM effort to redesign cities ‘in the general interest’ with a new focus on pedestrian urban ‘cores,’ Sert eventually developed the discipline of urban design.”48

This idea ran counter to the thinking within CIAM and in the dispersionist circles of American planning. Influenced in part by a splinter group of younger CIAM members known as Team 10, Sert broke with CIAM’s general deprecation of the density of older cities while hailing the cultural aspect of cities and great urban spaces such as “the Acropolis, the Piazza San Marco, the Place de la Concorde” as models of face-to-face pedestrian interaction.49 In fact, at the AIA conference at which he first used the term urban design, Sert represented one side of a debate about the future of American cities. Tracy Augur, a planner for the Tennessee Valley Authority, championed the other side, arguing that “urban centers make inviting targets” for atomic weapons.50 Sert disagreed, advocating a renewed focus on city-center redevelopment, albeit with reduced congestion and with new downtown parking facilities and modern roadways along the lines of earlier CIAM recommendations. In taking this tack, Eric Mumford writes, Sert set “the direction of much downtown urban renewal for the next few decades.”51

Three years later, in 1956, Sert hosted at Harvard the first conference dedicated solely to urban design. Participants included members of CIAM as well as such key figures as architect and planner Victor Gruen; Edmund Bacon, the head of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission; historian and urbanist Lewis Mumford; and writer and activist Jane Jacobs. Many historians agree that the conference gave birth to urban design as a distinct discipline with a specific focus on the renewal of declining core cities. “Urban design,” Sert said at the conference, “is that part of city planning which deals with the physical form of the city.”52

Harvard had already introduced a seminar on urban design, describing it as focusing on the “physical expression of city planning” and using the term urban design interchangeably with civic design.53 The 1956 conference, judging from its participants and their comments, represented a sincere attempt to solicit diverse viewpoints about the future of the city. Nevertheless, Sert’s view on the importance of retaining and rebuilding core cities as areas of civic engagement set the framework not only for the conference but for the future of urban design. “The urban designer,” Sert said at the conference, “must first of all believe in cities, their importance, and their value to human progress and culture.” He went on to describe the necessary process as “not one of decentralization, but one of recentralization.”54

Suburban dominance

“Detroit,” says urban designer Constance Bodurow, “spent the first fifty years of the twentieth century bringing the industrial age to America and then went to sleep for the next fifty years.” She points proudly to revitalization initiatives across her city, but her comments apply to much of urban America. In the late 1940s, mayors and chambers of commerce proclaimed a bright future for U.S. cities—an optimism that frequently proved premature. Instead, a perfect storm of economic, technological, and social forces dramatically refashioned the American landscape after World War II.

Migration to the suburbs tracked the transition in an economy that no longer needed mills and factories in urban centers. In America’s largest manufacturing cities, industrial jobs dropped by more than 40 percent between 1967 and 2001. This shift reflected a fundamental transformation not just of the economy but also of social classes. Median income rose sharply after the war, dramatically increasing the number of Americans who considered themselves middle class. With more money to spend on housing, Americans increasingly chose homes in the suburbs. Central cities soon gained a reputation as the province of working-class, poor, and nonwhite households—people who could not afford the suburbs (and who found their paths blocked by discriminatory lending and sales practices). Government housing programs of the late 1940s concentrated low-income housing in urban core areas at the same time that large numbers of Southern blacks trekked northward in search of industrial jobs and relief from Jim Crow laws. These factors aggravated a growing racial and economic gulf between city and suburb.

2.12 Renaissance Center, designed by architect John Portman and described as “a city within a city,” represents the high-water mark of urban renewal’s commitment to replacing traditional downtowns with “modern” auto-oriented urban centers. The Center’s location within downtown Detroit made it far more accessible by workers driving from affluent suburbs than it was from downtown, which sat isolated (or fenced off) from the complex by an arterial highway.

Courtesy Ritcheypro, via Wikimedia

Rising middle-class wealth together with high postwar birth rates drove demand for both home and car ownership. Fueled by government-insured mortgages, this demand spawned unprecedented tract-housing development; cities did not have the huge quantities of cheap land they needed to compete. By the mid-1950s, generous funding of the interstate highway system became yet another stream of federal subsidy supporting suburban development.

As suburban investment rose, urban investment fell. Middle-class and wealthier Americans not only moved out of cities, but they stopped working and shopping there as well. Although industrial uses began moving out of Northern cities as early as the 1920s, a massive relocation began after World War II. Trucks and interstate highways freed industry from the need to remain near big urban rail hubs. Air-conditioning and refrigeration removed yet another locational restraint. As a result, manufacturing gravitated to the urban fringe, deserting much of the northern United States, particularly its center cities and unionized workforce. By 1963, more than half of all the industrial employment in the United States had moved to suburban locations. Less than twenty years after that, almost two-thirds of manufacturing was taking place in industrial parks well beyond city limits.

By 1990, the real value of assessed property in the city of Detroit had dropped to less than a quarter of its 1950 level. Even though the decline elsewhere was less dramatic, almost every American city shifted rapidly from being a center of wealth to a center of poverty. Indeed, some suburbanites took pride in organizing their lives so that they never had to set foot in a downtown or urban neighborhood. By the 1970s, cities and traditional urban forms generally had taken on the air of outmoded relics of an earlier age.

Urban renewal: Remaking cities in an era when “what’s good for General Motors is good for America”

Even before the interstate highway system began to take shape, the car was fast becoming America’s travel mode of choice—and necessity. Virtually every plan from this time had to find innovative ways of dealing with automobiles. This problem principally involved how to capture the car and store it so that people could walk, shop, and engage in a fully pedestrian environment. In a paradigm-setting 1956 plan for Fort Worth, Texas, Victor Gruen proposed building a completely pedestrian urban core surrounded by a ring of parking structures all connected by a loop freeway. For Philadelphia, Louis Kahn proposed a series of parking garage “harbors” served by expressway “rivers.”55 Gruen’s plan holds special interest as it essentially recapitulated—on an urban scale—his 1953 plan for the first fully enclosed shopping mall in the United States: Southdale Center in the Minneapolis suburb of Edina.

Essentially, Gruen designed Southdale—which opened its doors in 1956—as a climate-controlled downtown shopping street anchored by department stores and dropped it into the center of a burgeoning suburb. Unlike a real downtown street, however, Southdale arose from scratch and offered ample parking. Moreover, both the public space within and the parking lots outside were privately owned. Gruen didn’t invent this concept, and he had designed earlier outdoor malls, notably Northland Center, which opened in 1954 in suburban Detroit.56 But Southdale proved a highly influential prototype for a generation of shopping malls that became the town centers and market squares for countless acres of otherwise centerless suburbia across the United States.

Despite their suburban origins, Southdale and Northland served as the basis for Gruen’s Fort Worth plan. Like them, Gruen’s plan for Fort Worth offered a fully pedestrian environment surrounded by parking; garages provided the interface between driving and walking. The main differences lay in scale, history, and ownership. Gruen’s suburban malls—considerably smaller than the one in downtown Fort Worth—were built de novo, had single owners, and sat amid vast fields of surface parking. The Fort Worth plan covered an entire existing downtown comprising multiple property owners. Additionally, despite its structured parking, the plan left much of the pedestrianized urban core outdoors. Finally, unlike an all-retail mall, the Fort Worth plan mixed both commercial and civic uses.57 (Because the State of Texas refused federal urban renewal money, the city could not assemble the funding to buy out downtown property owners—one reason the plan was never realized.)

Ironically, Gruen’s mall-inspired plan for Fort Worth largely followed the precepts that CIAM had laid out for urban centers at its 1951 congress. Foreshadowing Sert’s call for recentralization, CIAM 8 (called “The Heart of the City”) recommended that each city have only one core; that the core contain a mix of uses, including retail, office, and civic functions; and that it remain free of vehicular traffic, with cars parked at the periphery. Yet even in 1951 this was old news: Sert and other architects involved in CIAM (as well as others unaffiliated with the organization) had promoted this idea for nearly a decade. Nevertheless, Gruen’s plan for Fort Worth stood out for its clear application of the suburban mall model to an entire city, and it followed CIAM 8’s prescription for the urban core—hardly surprising, given that the suburban mall itself followed the model of a downtown shopping street.

2.13 Plan for Southdale Shopping Center (1953). The first enclosed mall in the United States, Southdale opened in 1956. It served as a prototype—albeit on a smaller scale—for many downtown-revival plans into the 1980s.

Courtesy Gruen Associates (formerly Victor Gruen & Associates)

The urban renewal model

By the early 1950s, the pace of urban disinvestment—spurred by federal investment in highways and low-cost mortgages, an exodus of white residents fearful of racially integrated living, the growing stigma of urban neighborhoods as places ill-suited for middle-class households, and the difficulties of accommodating cars—was a national crisis. Elected officials and their allies from industrialized states with major cities created the federal urban renewal program, which became the major source of funding for urban redevelopment until the mid-1970s. Echoing Burnham’s “make no little plans” spirit, the advocates of urban renewal demanded transformative federal investments in cities to restore their ability to compete with burgeoning suburbs for investment and middle-class residents and workers in an automotive age. Many projects from the urban renewal period of the 1950s and ’60s shared major traits:

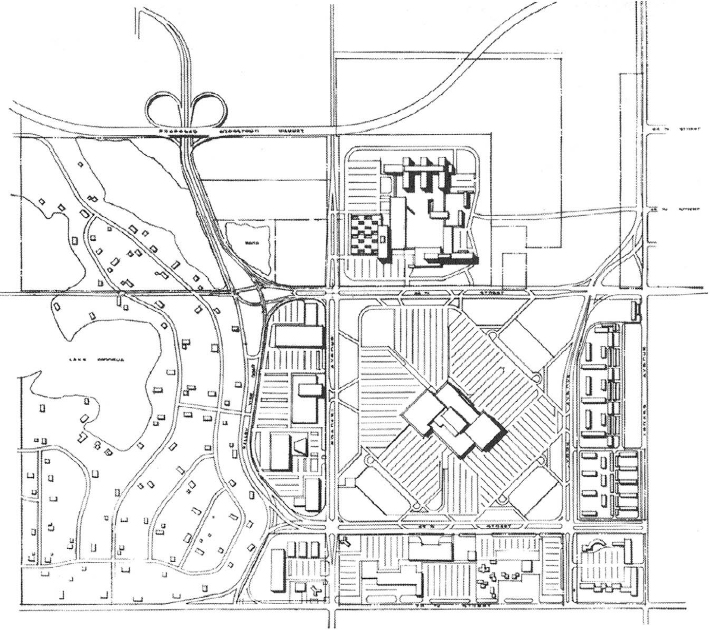

2.14 Plan for Fort Worth, Texas (1956). Architect Victor Gruen’s plan for downtown Fort Worth—a pedestrian core surrounded by garages for cars that arrived on an encircling freeway—recapitulated his earlier plans for suburban shopping centers and established a highly influential paradigm for rebuilding city centers in an auto-oriented age.

Courtesy Gruen Associates (formerly Victor Gruen & Associates)

- They were unabashedly modernist and monumental, that is, they embraced the aesthetic tradition developed by CIAM in Europe before World War II.

- They followed CIAM’s ideas by setting high-density towers and slab blocks within open space to allow light and air between the buildings.

- They attempted to rework existing urban patterns to accommodate the needs of automobiles by adding car-oriented roadways, superblocks, and interceptor parking in peripheral garages or hidden under platforms.

- They attempted to segregate pedestrians and vehicles, creating central pedestrian spaces or networks of pedestrian greenways, often on a different level from automotive circulation.

- They also segregated different uses, creating distinct zones along the lines of CIAM’s “functional city” recommendations.

A large majority of significant urban design undertakings from the 1950s through the 1970s were urban renewal projects heavily subsidized by government. Municipalities used powers of eminent domain to clear large tracts of inner-city and core areas—especially in the industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest—with the goal of introducing new life: the “recentralization” that Sert had called for. But not all of these efforts met the criteria that Sert and other urban designers had proposed, and many of those that did were built around vast civic pedestrian plazas fully separated from vehicular traffic. In retrospect, the underlying model—segregation of pedestrians and vehicles—proved a poor substitute for the lively streets, squares, and pedestrian networks eliminated to make way for these projects.

2.15 Empire State Plaza, Albany, New York. Separation of pedestrians and cars—in this case with a civic pedestrian plaza above a highway and parking—became the standard during the period of urban renewal.

Courtesy Jer21999, via Wikimedia.org

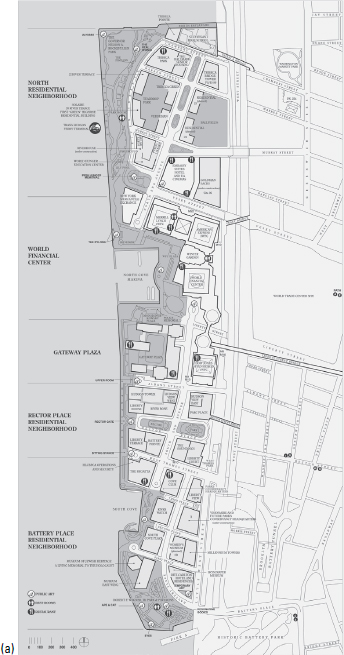

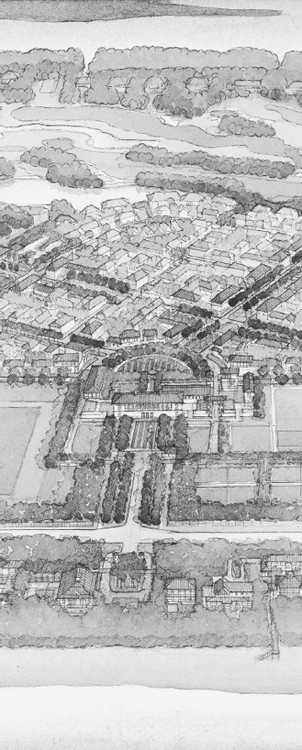

Urban renewal in Boston: A model for America

Redevelopment of central Boston, which began before the 1956 urban design conference and continued after it, paralleled the Fort Worth plan while embodying earlier CIAM ideas. Unlike the Fort Worth plan, Boston’s was actualized. Starting in the 1950s, Boston used the Federal Housing Act of 1949 to raze the historic but rundown West End neighborhood and replace it with a modern housing development called Charles River Park (Victor Gruen served as architect for the development). This attempt to provide new housing downtown as an alternative to suburban flight is a classic example of CIAM’s “towers in a park” concept, albeit with less room between towers than Le Corbusier would have demanded. It also conformed to modern CIAM-inspired zoning, replacing an older mixed-use neighborhood with a single-use residential district that confined commercial uses to peripheral development along adjoining streets.

2.16 (a) Boston before and during urban renewal. (b) Taken in the early 1960s, several key urban renewal initiatives are complete or well underway. The elevated Central Artery, not yet ten years old, cuts across the bottom of the photo. Above the highway at right, the low-rise, nineteenth-century buildings of the West End have disappeared; only the Massachusetts General Hospital campus remains, clustered near the river. The first buildings of Charles River Park—built on a model harking back to Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin—rise to the right of the hospital. The left edge of the cleared swath of land forms the site for the future Government Center and plaza. At top center, the framework of the Prudential building rises over former rail yards.

From the Malcolm Woronoff Family, Aerial Photos International Collection. © Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design.

During the same period, demolition proceeded on a corridor of buildings near Boston’s waterfront to make way for an elevated expressway. Planned to speed regional automobile access into downtown, the Central Artery connected on its northern and southern ends to roads that eventually became part of the interstate highway network. Negative reaction to both these projects, especially the demolition of the West End, drove a newly elected mayor in 1961 to hire Ed Logue, who had led redevelopment efforts in New Haven, as Boston’s chief planner.

Under Logue, most projects continued to follow Gruen’s model of using structured parking to intercept cars, so as to create exclusively pedestrian zones. Less than a mile from downtown, the Prudential Insurance Company undertook the construction of a monumental office tower on the Boston and Albany Railroad switching yard in the city’s Back Bay neighborhood. Charles Luckman’s design for the Prudential Center epitomizes many projects built in the 1960s. Planned as a superblock surrounded by a loop road, the Prudential Center followed the by then familiar Gruen model, although it tucked its parking beneath the complex rather than next to it. A plinth raised the center’s pedestrian level well above the surrounding streets. The mixed-use complex centered on the fifty-two-story Prudential Tower and included apartment and hotel towers, secondary office buildings, department stores and shops, and a convention center.58 These components sat atop the parking platform, like so many vacuum tubes plugged into the chassis of an early television set.

Other U.S. projects—including Constitution Plaza in Hartford, Empire State Plaza in Albany, the World Trade Center in New York City, Renaissance Center in Detroit, and Embarcadero Center in San Francisco—adopted the platform formula. In a plan for Stamford, Connecticut, an office complex known as the Landmark Center anchored a second-story pedestrian system for the city’s entire downtown. Never completed, the plan left some parts of downtown with a two-level system.

2.17 Prudential Center, Boston, Massachusetts (1960–65). This redevelopment project incorporated several of the era’s common characteristics: it followed Victor Gruen’s model of capturing traffic in a parking structure (in this case, underneath the development); it formed a superblock far larger than the basic unit of the adjacent grid; and it segregated pedestrian and automobile traffic.

In a fourth urban renewal initiative, the City of Boston leveled the delicate tracery of blocks that made up its red-light district, Scollay Square, after declaring it blighted. Use of the “blighted” designation said little about the neighborhood’s economic or physical condition but much about decision makers’ desire to remove poor people from the heart of the city and signal their own embrace of modernity. Where Scollay Square had stood, the city consolidated federal, state, and municipal offices in a complex of modern buildings, rechristening the area Government Center. The final master plan for the area by I. M. Pei & Partners organized every structure around a huge brick-paved plaza modeled on Siena’s Piazza del Campo. A long, curving midrise office building framed the western edge of the plaza, and a federal office complex designed by Walter Gropius defined its northern edge. A new city hall, the centerpiece of the project, anchored the plaza’s eastern edge, holding the same position as the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. With the exception of the federal buildings, no structure around the plaza rose higher than ten stories. City Hall itself had been the subject of a much-publicized competition won by the firm of Kallmann McKinnell and Knowles. Executed in the concrete brutalist style, the building won wide acclaim as a contemporary masterwork upon completion in 1969.59

2.18 Government Center, Boston, Massachusetts (1962–69). The complex of government buildings, planned by the architect I. M. Pei, replaced an energetic red-light district demolished in the early 1960s. Despite architectural praise for the city hall building, the vast pedestrian plaza often remains desolate, in contrast to lively mixed-use streets nearby.

Government Center, the quintessential urban design plan of the era, adopted the Fort Worth model. A large, adjacent parking garage intercepted cars from the regional traffic system in the hope that a driver’s downtown experience would occur on foot. City Hall Plaza deferred to this notion—its vast brick expanse was intended for public gatherings and to serve as a place of civic engagement along the lines Sert had laid out. In a remarkably similar exercise, the state of New York built Empire State Plaza in Albany, which gathered state government functions around a broad pedestrian plaza lifted above a platform of parking with direct highway access. It replaced the Pastures, a “blighted” neighborhood that was actually a stable Italian and Jewish district of Federal and Victorian houses.60 Remarkably, the state, which owns one America’s foremost contemporary art collections, chose to display its collection on the walls of the pedestrian arcades that served a shopping mall sandwiched beneath the pedestrian plaza and above an immense parking garage located in the project’s podium.

The design for Government Center failed to anticipate how little use the plaza would actually get. As quickly became clear, adjoining streets were livelier and more interesting than the plaza itself. Surrounded entirely by office buildings, it lacked any housing, which could have generated activity after 5:00 PM, and what little retail existed sat across a wide street with high traffic volume. Subsequent decades have produced a parade of proposals for redesigning and even eliminating the plaza.

Reactions to urban renewal

“After we have so painfully cleared away the old environment, dislocating hundreds of thousands of families, and after we have spent our billion dollars, will the new environment we create be worth the effort?” Edmund Bacon asked the seminal 1956 Harvard conference on urban design61 Indeed, that question troubled many people over the next twenty-five years. Some projects produced during the period won major awards but later fell into disfavor. Others, like Bacon’s planning initiatives for Philadelphia, enjoyed alternating periods of approbation and opprobrium. Still others, like Boston’s Government Center, continue to generate controversy today.

Preservation and rediscovery

America’s preservation movement emerged in the nineteenth century as a series of largely isolated local campaigns to save historic landmarks such as Mount Vernon in Fairfax County, Virginia, in the 1850s and Boston’s Old South Church in the 1870s. The early twentieth century saw a shift in focus from individual buildings to historic districts, starting with the creation of a historic commission for New Orleans’s Vieux Carré (French Quarter) in 1925 and the adoption of zoning protections for historic buildings in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1931. Formation of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1949 signaled the emergence of preservation as a national movement. While in its early decades the Trust focused on saving historic sites, preservationists organized themselves into loose coalitions to oppose the destruction of the traditional urban fabric that almost always accompanied urban renewal projects. By the early 1970s, these informal groups in cities across the United States had emerged as pioneering advocates of urban neighborhoods as places of choice, not last resort.

In 1963, the New York City Planning Commission granted a variance allowing demolition of Pennsylvania Station to clear the way for construction of a new Madison Square Garden and an office complex. The commission found no legal basis for denying the variance, as no law then protected historic buildings.62 The destruction of McKim, Mead & White’s masterwork provoked widespread condemnation as a national tragedy, but it galvanized the historic preservation movement. Once the preserve of a small number of wealthy Americans, the movement expanded dramatically during this period, as preservationists joined forces with community groups to protect endangered neighborhoods from highways and urban renewal projects. Within three years of the Penn Station debacle, New York City had put in place a landmarks preservation law and Congress had passed the National Historic Preservation Act.

Penn Station’s demise accelerated a dramatic shift in American thinking about the value of cities already underway. Buildings that architects, planners, and others had once dismissed as blighted now enjoyed new critical approval as valuable historic resources. The delicate network of lively urban streets and blocks appeared to offer an alternative to urban sprawl and modernist superblock planning schemes. The seminal Death and Life of Great American Cities had appeared in 1961, written by Jane Jacobs, a senior editor at Fortune magazine. Inspired in part by her experiences working to block construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway in the 1950s, Jacobs advanced the idea that urban renewal destroyed precisely the things that made cities great: the intimate scale and complex social networks found in, say, Greenwich Village, where she lived. She exhorted planners to “go back and look at some of the lively old parts of the city. Notice the tenement with the stoop and sidewalk and how that stoop and sidewalk belong to the people there.”63

“Cities,” she wrote, “need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them.”64 At the same time, she wrote, “the continuity of . . . movement (which gives the street its safety) depends on an economic foundation of basic mixed uses.”65 Small blocks, she said, not vast superblocks, give cities vitality and provide the qualities that make them better and more interesting places to live than suburbs. Prominent academics and intellectuals joined Jacobs—including Lewis Mumford, William H. Whyte, and Ada Louise Huxtable—and a groundswell of opposition soon became a tidal wave as residents in city after city protested the destruction caused by highways and urban renewal.

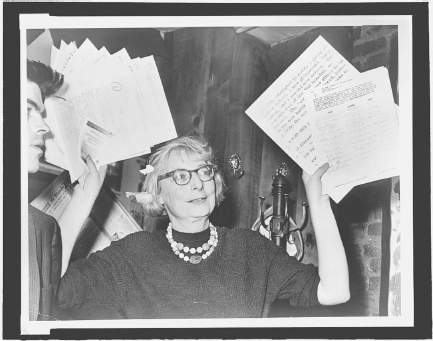

2.19 Writer, activist, and urban theorist Jane Jacobs. In her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs set out the intellectual underpinnings of the reaction to urban renewal and its modernist precepts. She argued that the very qualities that car-focused urban renewal destroyed—varied buildings, intricate social networks, and pedestrian street life—were precisely what make cities successful. Her thinking continues to influence urban design today.

Courtesy Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection

During this same period, an MIT professor catalogued the elements that make a city viable for its citizens—the constituent parts that people use to orient themselves and travel through a city. In The Image of the City (1960), Kevin Lynch analyzed the features that contributed to what he called the “imageability” of a city. In this and subsequent books, Lynch found that the most “imageable” cities often turned out to be the more historic ones—Venice, San Francisco, and Boston, for example. Such places tended to contain more iconic buildings and features—that is, more memorable structures and places—such as the Piazza San Marco in Venice, the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, the art deco John Hancock Building in Boston. While some newer plans introduced identifiable markers in certain cities, a growing number of architects and urban designers felt that the industrial anonymity of modernist buildings (a logical outgrowth of the machine aesthetic promoted by modernists and CIAM) lacked this quality of imageability. Essentially, these new projects might arise in any city; nothing distinguished a modern building in Dallas from one in Denver or Detroit.

Other factors contributed to cities’ distinctiveness independent of the work of architects, planners, or urban designers. Older neighborhoods like Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, Boston’s South End, San Francisco’s North Beach, and Philadelphia’s South Street had continued to attract artists, writers, and others who steadfastly refused to move to the suburbs. These people formed the nucleus of grassroots movements that began to transform entire districts of older cities without government help—and sometimes without government approval.

In the 1960s and ’70s, a gradual exodus of garment manufacturing from Lower Manhattan left behind an exemplary collection of nineteenth-century loft buildings. Low rents and large spaces attracted painters, sculptors, photographers, dancers, and other artists who used these buildings as both work and dwelling space. The City of New York initially discouraged this movement because it violated zoning laws and seemed likely to drive remaining factories—and their well-paying jobs—out of the city. But the movement nonetheless exploded in the 1970s, as others began to follow artists into the lofts. By the 1980s, SoHo and neighboring Tribeca had become fashionable addresses. Over a twenty-year period, these old industrial buildings were recycled into new, mixed-use residential and commercial neighborhoods that had never existed before, with rehabilitated loft condominiums eventually selling for millions of dollars.66

Manhattan offers only one example of the grassroots reinvestment that began in the 1960s. Urban pioneers began fixing up and restoring old buildings in neighborhoods like College Hill in Providence, downtown Charleston, South Beach in Miami Beach, Ybor City in Tampa, Virginia Highlands in Atlanta, Pittsburgh’s North Side, Lincoln Park in Chicago, Lower Downtown in Denver, and in neighborhoods in many other cities. Although initially antagonistic, most city governments ultimately became active supporters of the movement. This change in perspective owes much to the work of Jane Jacobs and her political and intellectual allies who staked out the battle lines against urban renewal and urban highway building in the 1960s.67

At about this time, some of the huge public housing projects inspired by CIAM and modernist ideals (or, more accurately, a misunderstood and poorly executed version of those ideals) fell victim to major operating problems. Instead of improving the lives of residents, these complexes—with structural deficiencies and social ills contributing in equal measure—made residents’ lives worse. The iconic 1972 demolition of the troubled Pruitt-Igoe complex in St. Louis highlighted this turn and undermined CIAM’s notion of the architect-planner as an able agent of social improvement. Turning away from CIAM’s influence, urban designers across America moved toward the Jacobs camp, and a new idea of urban design began to take form.

Utopianism

In 1967, more than fifty million people from around the planet flocked to Canada for Expo 67 in Montreal. Many found themselves enthralled by one of the fair’s iconic structures, Habitat 67, a hill of giant concrete boxes that looked randomly thrown together. The apparent chaos, in fact, belied the exacting thinking behind the boxes’ arrangement. Each industrially fabricated module joined with one or two others to make a dwelling unit replete with landscaped terraces that sat on the roof of the unit below. Habitat was, in fact, a painstakingly planned megastructure, an industrialized casbah, and its architect, Moshe Safdie, became famous overnight. To many, it seemed a revolutionary vision of the future of cities and housing.

Utopian visions abounded in the 1960s, but unlike Habitat 67, few were actually built. In the Arizona desert, Paolo Soleri worked on a utopian megastructure called Arcosanti.68 In Japan, Kenzo Tange proposed a megastructural plan for Tokyo Bay, and Arata Isozaki set out plans for his Joint Core Stem urban system. In Great Britain, three years before Expo 67, Archigram—a loose federation of avant-garde English designers who produced theoretical designs—proposed the Plug-In City—live/work modules that could be moved at the owner’s whim from one towering infrastructure frame to another. The collaborative devised many other unorthodox schemes, including one for a city that moved on massive hydraulic legs.69 In 1968, Paul Rudolph unveiled a proposal that would have combined four thousand units of housing with offices, schools, and factories in a single massive structure built in Lower Manhattan.

2.20 Habitat 67, Montreal, Quebec. Although it looks like a haphazard pile of boxes, Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 was actually a carefully planned housing development. Built for the 1967 world’s fair in Montreal, it stands as one of only a handful of 1960s megastructure plans that were built.

Photo by Tim Hursley

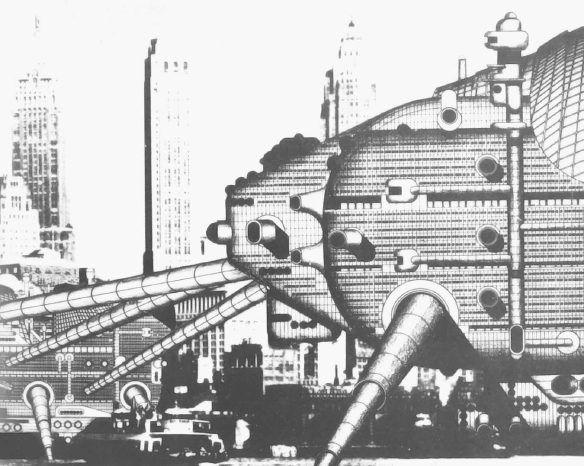

2.21 Walking City. One of many unbuilt megastructures from the 1960s: Archigram’s 1964 plan for a city that moves on massive hydraulic legs.

© 1964 by Ron Herron. Courtesy of the Ron Herron Archive

Inspired, as CIAM had been, by the idea that housing could be mass-produced, these designers extended the idea of industrial production to other urban building types and systems. These projects pushed CIAM’s theory of the functional city to an occasionally fantastical conclusion, turning transportation and utility systems into organizing spines and cores that housing and other building types could plug into. (CIAM’s elegant towers, surrounded by light and air, sometimes vanished entirely within the structural maze some of these projects created.) While European countries did complete housing that borrowed some practical aspects of these utopian ideas, few such structures broke ground in the United States, where a strong backlash was brewing. Nevertheless, unbuilt utopian projects from this period remained an inspiration for later architects and urban designers.

Reform

As early as the 1960s, city governments began to modify or abandon their approach to urban redevelopment. Without walking away from big housing and redevelopment initiatives, they began to incorporate mixed-use and infill projects that respected existing urban neighborhoods. The skyrocketing price of gasoline in the 1970s refocused thinking on mass transit as an alternative to highways and parking garages. City governments began to take up what had been a grassroots cause, restoring historic neighborhoods and downtown subdistricts, often with federal or state funds earmarked for urban renewal. In the 1970s, Newburyport, a faded seaport north of Boston, reversed course in the middle of demolishing its historic, Federal-style downtown. Instead, the municipality listed the district on the National Register of Historic Places and used the remainder of its federal urban renewal funding to launch a massive restoration. The resulting Market Square Historic District project became one of the first AIA Honor Award winners to encompass historic revitalization of a major portion of a downtown.

Less than an hour inland from Newburyport, the rundown mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, used National Park Service funding to transform its dying center into a national urban cultural park. Adding federal urban renewal funds, and with the active support of the state, the city sparked the recycling of thousands of square feet of abandoned mill buildings into offices, homes, and museums. Other cities identified and began restoring key parts of their historic downtowns. Philadelphia had already begun work on its Society Hill neighborhood. In Seattle, Pioneer Square became a center of revival efforts. San Diego focused on the Gaslight District. Denver residents organized to reclaim Capitol Hill, and Providence began refashioning both the College Hill and Federal Hill neighborhoods.

A major restoration project of the period became widely influential: Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace, created by the Rouse Corporation and architect Benjamin Thompson. Winner of an AIA Honor Award, the project converted a wholesale food center into the nation’s first “festival marketplace” by rehabilitating three huge nineteenth-century market halls and transforming the surrounding sea of asphalt into beautifully landscaped pedestrian space. Here was a vibrant urban environment that encouraged true civic engagement and enjoyment. Located on Boston’s Walk to the Sea, the marketplace created an exciting transition from the “New Boston” at City Hall Plaza to the city’s historic waterfront, where wharf buildings were undergoing rehabilitation for residential use. The marketplace set a national standard for urban retail development and historic building reuse; variations exist in cities across the United States, including the highly successful Harborplace in Baltimore; Jacksonville Landing in Florida; and Navy Pier in Chicago. As much as it became a new paradigm, Faneuil Hall Marketplace in many ways simply adapted the familiar Gruen model, creating a pedestrian shopping zone attached to a large parking garage with near-direct highway access.

2.22 Newburyport, Massachusetts. Making a midcourse correction, the city abandoned an urban renewal project, listed its downtown on the National Register of Historic Places, and redirected unused urban renewal funds to restoration. The historic preservation movement emerged in the 1970s as an alternative to urban renewal, offering an approach to downtown revitalization that focused on restoring rather than replacing urban fabric.

Courtesy of Oliver Gillham

By the late 1970s, communities across the United States had begun restoring historic downtowns and Main Streets with newly available federal funds and tax credits. In 1977, the National Trust for Historic Preservation launched its Main Street program, designed to spur economic development by preserving the historic commercial architecture of declining downtowns along with other cultural and historic resources. By 2013, the program had reached more than two thousand American communities.70

All these efforts aimed to revive downtowns that had suffered from suburbanization. That work continues nationally as downtowns adopt standard-practice storefront-revitalization programs and signage guidelines and install new paving, landscaping, and lighting. Revitalization plans have often combined these initiatives with new parking facilities (following the Gruen model) and targeted redevelopment and adaptive reuse of existing downtown buildings.

2.23 Faneuil Hall Marketplace, Boston, Massachusetts. The first “festival marketplace” became a national model for urban retail development and adaptive reuse.

Photo © 2006 Chris Wood, via Wikimedia.org

Looking back for inspiration

Postmodernism and contextualism takes root in cities

Postmodernist and contextualist architectural movements emerged in the late 1970s as complements to the growing historic preservation movement. Both movements challenged the dominance of modernism and the industrial aesthetic in architecture, advocating a return to the historic orders, decorative detail, and scale of premodernist architecture—often with a contemporary twist. Art deco reinterpretations became popular alongside more purely historicist approaches, as seen in buildings designed by Robert A. M. Stern or in Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s One Worldwide Plaza in Manhattan, which reflected architectural styles from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.