Chapter 6

Urban Design for an Urban Century: Principles, Strategies, and Process

For roughly sixty years, the American dream of a community shaped around a suburban single-family house with a yard and two cars in the driveway promising easy access to jobs, shopping, recreation, and education served as a near universal template for shaping American communities. This dream drew on a powerful American belief in self-reliance and the rewards of individual endeavor. A man’s home was his castle, went the pre-feminist formulation, and hard work would guarantee anyone the ability to buy that castle.

The dream grew naturally from its era. In the 1950s and ’60s, individual hard work did pay off for many Americans: the middle class grew while income disparities shrank; industries and their jobs stayed put. The “environment” for most people meant a national park. A sense of community developed naturally in ethnically and culturally homogenous neighborhoods: three-quarters of all households included children, and residents in the same neighborhoods shared the same schools, parks, and churches. Main Streets were for running errands. In an entirely human reaction to two decades of economic depression and wartime privation, most Americans concentrated on achieving middle-class economic status and enjoying the material comfort that came with it—most visibly, a chance to trade the confines of a small urban apartment for a car and a detached house in the suburbs. While this picture oversimplifies the era, it does suggest a widely shared and culturally reinforced system of perceptions and ideals. Most Americans considered them common sense.

This belief system combined two sets of values that can appear contradictory, one with deep roots in the American psyche and one that became widely influential only after World War II. Dating back to the Colonial era, owning land had mattered, conferring the right to vote in the early days of the republic, lauded by the Founding Fathers as a bulwark of democracy, and endorsed by waves of European immigrants who arrived throughout the nineteenth century. That ingrained tradition joined with a self-conscious desire to embrace the new and “modern” that emerged after World War II. The modernist movement increasingly influenced American culture during this period with its dismissal of all things old-fashioned. In architecture and planning, it sought to replace traditional urban form (styles, materials, and the relationship of buildings to each other and their settings) with new forms and physical environments considered more rational, egalitarian, and democratic. In a sense, the modernist impulse combined with the established love of land ownership to articulate a moral rationale for suburban living. Not only did suburbia offer middle-class families an opportunity to own their own castles, it was also an opportunity cast off the pall of the Depression and the war and celebrate the values of this new age.

The American dream circa 1960 no longer fits American society today, which by comparison looks like an alternate reality. Today the middle class continues a decades-long contraction, income disparities have returned to the levels of the 1920s, and owning one’s own castle has moved beyond the reach of millions of households. Today hard work is most likely to pay off if it sits on the foundation of an expensive college education, but economic circumstances for roughly one-third of Americans make this education impossible to attain, and for another large slice of the population it requires painful sacrifice to pay for. Cities today compete to attract highly mobile knowledge industries and jobs. The word environment often seems married to the word crisis. Neighborhoods have become more fragmented economically, and with far fewer children (today living in only one-quarter of all households), the sense of community that once derived through shared schools today seems difficult to achieve (new technologies that have turned communication and play into solitary pursuits hardly encourage a sense of community). Main Streets have become “third places,” less shopping destinations than alternatives to home and work and hoped-for antidotes to isolation. Realtors today tout a property’s Walk Score—a measure of walkability—the way their 1960s counterparts highlighted the quality of the local schools or easy highway access. Authenticity matters. Whereas 1960s eyes saw row house neighborhoods as outmoded and single-family subdivisions as satisfyingly modern, today’s eyes see the row houses as beautiful and the subdivisions as stultifying.

When Josep Lluís Sert proposed the concept of “urban design” at a formal conference held at Harvard in 1956, he assigned it a goal well outside that of the then-prevailing idea of the American dream: reviving cities at a time when economic, political, and social forces all strongly favored suburban development. Sert knew that decaying cities faced much more complex challenges than booming suburbs. He acknowledged that complexity by describing urban design as an integration of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning with a mission “wider than the scope of these three professions.”1 Reviving cities would require an in-depth understanding of tangled social, economic, and cultural forces. It would also require a broadened definition of “design.”

By the 1950s, architecture had fully embraced the modernist movement, in part as a reaction to thirty years of social inequality, militarism, and economic trauma in the United States and Europe. Modernism transformed architecture, including its subspecialty “city design,” into a fine art that sought generally to create beautiful works rather than a civic art that aimed to balance aesthetics and function. Urban renewal—a broad movement to rebuild “archaic” city centers to accommodate cars and match an academic notion of “modern”—showed the dangers of divorcing city planning from social, cultural, economic, and environmental realities. Sert wanted to destroy the idea of architecture and landscape architecture as fine arts that produced beautiful building-objects. By integrating these disciplines with planning, he thought, urban design could emerge as a social or civic art whose charge was the creation of successful communities.

Chapter 3 described dramatic changes in the conditions that gave rise to the midcentury American dream. A new constellation of forces has given cities—and urban design—new prominence. Chapter 4 dealt with opportunities for urban communities unimagined since the Great Depression, and chapter 5 enumerated schools of urbanism whose theories offer different approaches to achieving these goals. Together these chapters suggest that the time has come to formulate a new and more urban American dream. This chapter doesn’t attempt to do so, but it does offer something just as important: an urban design paradigm that adapts Sert’s idea of a civic art to the realities of America in the twenty-first century. This paradigm starts with principles for applying urban design—concrete and designed with plenty of flexibility to address the varying dynamics that govern a given time and place. These principles build on Sert’s belief that urban design represents a melding of planning and design. They also recognize that today policy also plays a central role in shaping urban design outcomes.

Principles

The previous five chapters set the stage for identifying core principles to guide urban design for this era. These principles begin with enhancing livability, which in turn represents a key step toward achieving the second principle—creating a greater sense of community. Together, these are prerequisites for the principles of expanding opportunity and promoting greater equality. Finally, these four form a necessary foundation for the fifth principle: fostering sustainability. We don’t claim these principles will prove timeless or are universal. They do, however, identify essential priorities for urban design over the next decades of extraordinary growth and change in the United States. The principles, and the strategies that go with them, will need to evolve in response to changes in demographic, economic, social, economic, cultural, and environmental conditions.

- Enhance livability: Offer the widest possible individual choices for living healthier, more satisfying lives.

- America abounds in drivable environments that offer limited choices for living, working, shopping, and entertainment. That model might have worked universally in 1960, when mass-market culture ensured that everyone could find satisfaction by choosing from a few defined options. But that doesn’t work today. We live in a far more diverse society and have the capacity to connect with people of similar tastes and interests to create smaller but viable markets (land use economist Leanne Lachman calls the United States today “a nation of niches”). Today, livability benefits strongly from walkable environments that offer ready access to a broad range of life choices, and urban designers should make creating such environments their top priority.

- Create community: Invite people from all walks of life to engage each other.

- For generations, most Americans of all races and incomes found ready community in the churches, schools, parks, and even workplaces they shared. Ironically, segregation, suburbanization, and single-use zoning reinforced the homogeneity that nurtured this sense of community. As America increasingly becomes a “nation of niches,” people increasingly seek the experience of community that American life no longer provides as a matter of course. The work of urban design is to nurture that sense of community.

- Expand opportunity: Make cities and regions more economically competitive.

- As knowledge industries grow more important to the U.S. economy, thriving cities become essential to regions hoping to lure better jobs and the investment the companies hiring for those jobs bring with them. Cities can provide the dense, walkable environments that attract talent, promote culture, and nurture innovation. The trillions of public dollars invested in regional highways and sprawl since 1950 have undermined cities’ ability to do these things, in the process leaving them ill-prepared to compete in a global knowledge economy. Urban designers must equip cities to compete by creating livable, community-rich urban centers.

- Promote equality: Advance equitable access to livability, community, and opportunity.

- A growing “opportunity gap” has raised income disparities to record levels and pushed millions of poor Americans out of center cities and further from access to transit, jobs, healthcare, and education—the very resources they need to succeed. Displacement deepens the misery, longevity, and social costs of poverty—which research shows degrades quality of life across all income and social levels. Urban design plays a central role in creating environments that help make society more equitable.

- Foster sustainability: Pursue a full agenda of environmental responsibility and resilience.

- A growing awareness of the costs of sprawl and the rapid acceleration of climate change have set the stage for a new era of regional cooperation. Governments will spend tens of trillions of dollars to improve environmental performance, reverse sprawl, and achieve resilience. Urban designers have a responsibility to ensure that investments in resilience translate into improved livability, community, opportunity, and equity.

Strategies for Achieving the Principles: Policies, Planning, and Placemaking

Urban design relies on three core strategies: policies that translate political, social, environmental, and similar values into concrete goals; planning that provides a broad framework for achieving these goals; and placemaking that translates these frameworks into the physical environment we inhabit.

Table 6.1 Policy, Planning, Placemaking

| Policy | Planning | Placemaking |

|---|---|---|

| Create a comprehensive transportation network |

|

|

| Concentrate growth in transit-served nodes. |

|

|

| Promote social and economic inclusion. |

|

|

| Create a complete public realm. |

|

|

| Create “common grounds.” |

|

|

| Plan and design to promote environmental responsibility. |

|

|

| Promote smart growth. |

|

|

| Build in resilience: reinforce rather than relocate communities. |

|

|

| ∗FAR: As defined in chapter 4, floor-area-ratio, a measure of density and intensity of site coverage. A FAR of 1.0 for a parcel, in its simplest form, means a one-story building that covers the entire parcel. That massing, however, could be arranged in other ways to cover less of the parcel with a taller building. For example, a building that only covers one-quarter of the parcel would still have a FAR of 1.0 if it were four stories high. For the purposes of this discussion, FAR is based on the net buildable site, not including public streets, parks, and environmentally protected areas. | ||

Process that Supports the Principles

The devil you know: Moving past NIMBY

The architect Michael Pyatok, widely admired for his mixed-income urban housing, argues that a term often used to criticize opposition to development, “NIMBY” (not in my back yard), oversimplifies and misstates neighborhood concerns. “Today,” as he noted in a 2012 address, the increasingly uncharted nature of urban growth “brings change to people’s front doors . . . and in most cases that change is not exactly familiar or instinctively welcome.”2 Saying no to unfamiliar change can be a fully rational default reaction when the speed of development has accelerated and the scale of development has increased. Many communities may legitimately fear a repeat of negative impacts that resulted from previous development—including increased traffic, gentrification, and loss of traditional neighborhood character. A city hall, hospital, or recreation center can trigger this reaction as readily as an office building or housing development. It can occur in a suburb or a city, in rich or poor communities, and across regions or in a specific neighborhood.

Until roughly thirty years ago, urban design operated essentially as a command-and-control process. From highways that cut entire neighborhoods in half to urban renewal measures that eviscerated others, this model rarely produced the best plans (which, in a top-down process, may not even be the ultimate intention). Command-and-control works when a leader—a mayor, a university president, or a developer—can execute a plan regardless of community buy-in. It has become increasingly rare, because the idea that a project can succeed without community support almost inevitably turns out to be wrong. Where it does occur—for example, in the early recovery planning for New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina or in the wholesale conversion of large industrial districts—urban designers carry an extra responsibility to seek out stakeholders, possibly from focus groups or proxies, who can best represent the perspectives of stakeholders who lack a voice in the process.

Proponents of top-down planning often argue that it saves time and enables experts to develop a better plan than a “messier” open process would yield. Aside from the ethical weakness of that argument, community-based urban design—the second approach—has generally yielded better plans and makes implementing a plan much easier. A community-based process draws ideas from diverse stakeholders, provides a forum for testing those ideas from multiple perspectives, and compels participants to work with one another to define and improve cost/benefit trade-offs. In an era of increasingly scarce public resources and a growing role for public/private partnerships, a community-based process delivers two additional benefits: it brings decision-makers and funders to the table from the start, and it builds the widespread political will necessary to make a strong claim on resources—both public and private. This is the kind of process that supports the principles set out above.

What can happen when change knocks at a neighborhood’s door? Alexandria, Virginia, offers a useful illustration. The beneficiary of a strong regional economy, endowed with miles of waterfront, and served by one of the country’s best regional transit systems, Alexandria’s neighborhoods sit in a strong position to realize the benefits of the current urban revival.

As her first major project, the city’s then new planning director, Faroll Hamer, invited residents of one neighborhood to help the city create a transit-oriented district plan that would take advantage of the presence of a Metro rapid transit station. Hamer and the city envisioned new, high-value development on vacant land close to the station, whose benefits could include transformation of concentrated public housing into mixed-income housing; funding of a needed park; easing a shortage of retail that served the neighborhood; and addressing other longstanding problems. Community leaders had balked at similar planning efforts for five years, during which the city presented ambitious proposals from respected developers, explained their benefits, asked for community support—and met full-throated resistance. Neighborhood leaders knew that planning within a ten-minute walk of any Metro station in the region raised the possibility of significant new development. They disliked the status quo, but the prospect of more intensive development—no matter the reassurances offered by the city’s planners—sounded worse.

Hamer decided to change the process. She invited stakeholders to engage in a community conversation, with no topic barred, and then to plan. She brought in consultants and speakers, sponsored workshops that brought together public housing residents and newly arrived professionals, and led neighborhood walking tours. The conversation began by asking community members to set the agenda. What did they like about the neighborhood? What did they want to change? How did they think the community should approach the starkly different opinions of longtime public housing residents and affluent new residents? Where was the common ground? As the discussion proceeded, participants began to translate anxieties into questions. How do we decide what kind of higher density—if any—is good for our neighborhood? How many new residents and what kind of development would it take to support a new neighborhood Main Street? Does mixed-income housing really work—and in the marketplace, not just in the hearts of city officials?

Consultants provided hard data about the economics of redeveloping public housing into mixed-income housing and the densities required to prevent the displacement of current residents. Residents were invited to explore trade-offs such as lowering below-grade parking requirements in return for requiring developments to share the cost savings by investing in a new park and street trees. The city and its consultants provided information about the feasibility of developing a public square lined with neighborhood retail to replace a parking lot across from the Metro station—including the densities required to fund a lively public space. Community members then worked with consultants to create design guidelines that shaped the necessary height and density in ways that would respect adjacent row house blocks. The city openly debated alternative implementation strategies with community members—for example, height and density bonuses in return for additional community benefits and different approaches to design review—and invited community leaders to take a substantive role in managing implementation.

Conversation morphed into an urban design process on the community’s terms, and eight months later Hamer had achieved a remarkable turnaround: strong neighborhood support that crossed lines of race, income, and other divisions, together with unanimous City Council support for a plan shaped around urban design principles that put forces for growth and change in the service of the full community’s needs and aspirations.

Community-based urban design: Early in the process

Urban design starts with the stakeholders

Identifying which stakeholders need to participate in the process starts with questions. Who will be affected by the outcome? Who lives, works, operates a business, or owns property in the study area? What agencies, institutions, developers, or other potential funders will be responsible for implementation? Who are the elected officials or other decision-makers? What historic preservation, sustainability, or other advocates have a stake in the outcome?

Bringing all these stakeholders together to listen to one another, absorb the same technical information together, learn to trust one another, and ultimately make trade-offs and decisions together represents a critical first step toward layering ideas necessary to craft a relevant, rich, and nuanced vision that captures a community’s spirit and enjoys widespread support. The full spectrum of the community should be directly involved in the process from start to finish. At the same time, an advisory committee that represents points of view across this spectrum and meets (and debates) regularly plays a particularly valuable role—as community leaders empowered to make decisions and as advisors to the urban designer in shaping the plan (and sometimes the process as well) by adding the right information and perspective.

There is no right way to engage stakeholders. Different approaches work in different circumstances. A politically divided community may require a series of workshops and charrettes over several months to find common ground. In other communities, an intensive multiday charrette (a method favored by New Urbanists) can produce a great plan as well as support for its implementation. No matter the structure chosen, however, certain ground rules can have a positive impact. These include transparent information sharing and decision-making; agreeing that “100% of zero is zero” (meaning that trade-offs produce better results than refusing to compromise); and a commitment to granting every participant the right to speak freely without retribution in another forum or later in the process. Still relatively new as an urban design tool, social media have demonstrated rich possibilities for broadening engagement in the form of dedicated Twitter feeds, Facebook pages that encourage feedback, crowd-sourced mapping tools for pinpointing areas that require attention or offer new opportunities, and online polling tools like SurveyMonkey.

6.8 No single approach to engaging the community works universally. Most processes benefit from a round of (often extensive) one-to-one meetings with key individuals and groups to ensure that everyone has the same understanding of the issues and that everyone gets to know one another in the context of a shared task. After all stakeholders’ perspectives are understood, the moment is right to bring the full range of stakeholders together—across lines of income, race, background, role in the process, and other differences—to move from a parallel to a shared planning process.

Courtesy of Goody Clancy

Every idea develops its meaning from its context

Context involves far more than the study area and its vicinity. It begins with learning and documenting the full spectrum of stakeholder needs and aspirations. Context also means understanding what mix of physical, social, economic, cultural, and environmental issues will shape urban design and determine its success or failure. These will include national demographic, economic, and other trends that have local implications. Yet context must also incorporate a clear sense of place. What are the physical conditions—surrounding uses and character, topography, and views? What are the environmental and climate conditions? Can the project build new social connections between racially or economically divided communities? Can it create amenities that will attract knowledge workers and the investment that follows them? Can it take advantage of predictable demographic changes, from a surge of school-age children learning English as a second language to a wave of retiring baby boomers? Can additional density fund a desired performance hall or theater? Can the project form the nucleus of an eco-district?

Stakeholders as educated decision-makers

A successful urban design process is in many ways a community-education process. From beginning to end, the urban designer and community members learn from one another. Conveying data and studying their implications in public sessions can build a shared and realistic understanding of opportunities and challenges. A transparent process builds trust among all participants and can defuse opposition from skeptics or people working with outdated information. Participants in the community-education process deserve real information and make far better decisions when they have it. A fully informed process will likely not only produce better results, but produce them faster and with more political momentum: diverse stakeholders armed with the same information and understanding are far more likely to reach consensus.

Inject implementation strategies into every step of the process

The reality of reduced public resources today means that most projects require complex public, private, and institutional partnerships to ensure funding, management, and implementation. Considering potential implementation strategies at the process’s inception can identify key stakeholders and help determine the program mix for a real estate development (for example, which uses would create the value needed to pay for affordable housing, public space, or other civic benefits for which no public money exists). Making all stakeholders aware of implementation issues from the start can set realistic expectations and help a community understand the need to build broad political support to secure funding for an ambitious project. Bringing potential partners to the table at the start helps all stakeholders understand one another’s goals and gives them a chance to shape a project that meets multiple goals—and has a better chance of winning the support of multiple partners.

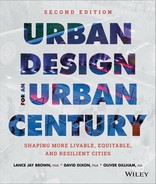

SOURCE Zimmerman/Volk, 2013

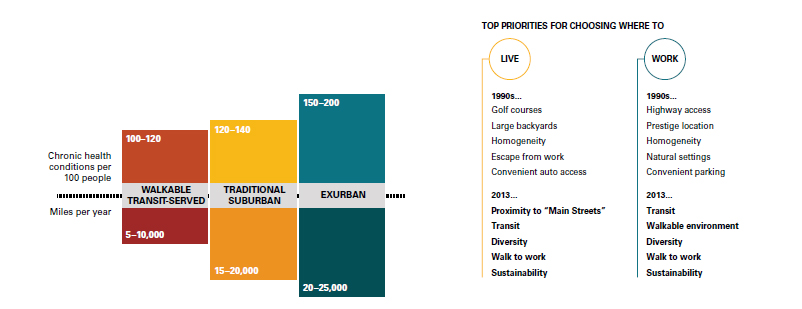

SOURCE Arthur C. Nelson, keynote lecture, Pace University Land Use Law Center Annual Conference:“Places for People” (2012)

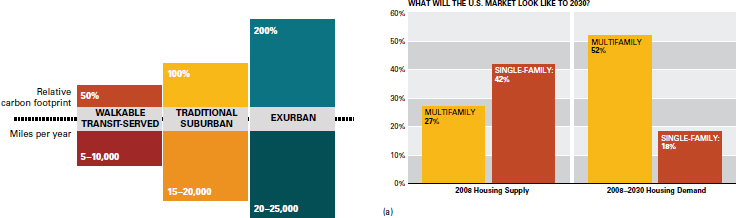

SOURCE Arthur C. Nelson, keynote lecture, Pace University Land Use Law Center Annual Conference:“Places for People” (2012)

6.9 Information that bears on a variety of perspectives—social, economic, and environmental—is critical to providing stakeholders with an understanding of the challenges and opportunities that face them and their community.

Courtesy of Goody Clancy

Midway through the process

An achievable vision

Every plan should include a vision—a compelling picture of the future that meets the needs and captures the aspirations of the community. It functions as a kind of mission statement for the community and an organizing framework for the plan itself. A poor understanding of implementation options or an overly ambitious vision can make a plan unworkable. That plan will sit on the shelf (the profession’s code for a plan that never gets implemented) and waste the time, money, and community energy spent on developing it. Plans that are never implemented undermine the value and credibility of urban design.

Part of creating a vision is determining when sufficient information, analysis, and perspective are in hand. Crafting the vision too early can yield a plan that fails to address the full range of opportunities and challenges or does so in a tentative way because participants lack confidence in the implementation. Achievability lies in identifying a believable path to implementation for every concept within the plan document. Funding or legislation may not yet be in place, but each recommendation has a champion, a believable near- and longer-term funding strategy, and broad political support.

Giving form to urban design

An urban design vision exists in two dimensions. One is placemaking, a framework for the physical qualities of a place that may encompass a plan of streets and squares; the scale, character, and quality of the buildings that frame this public realm; the experience of moving through the spaces the plan creates; the way development fits with nature; vistas to and from the plan area; and other qualities that define the experience of a place. The second involves the functions of a site—decisions about the uses that occupy buildings and public spaces; access to transit; diversity of incomes, ages, and backgrounds; and other policy and planning decisions that will bring a physical place to life.

6.10 Equipped with a shared understanding of the issues and trends, a highly interactive charrette in which stakeholders from every neighborhood and livelihood work together and make trade-offs can lead to a vision that is both fully achievable and more ambitious than visions brought to the process by different groups of stakeholders.

Courtesy of Goody Clancy

6.11 Bringing stakeholders together around a shared vision yields enthusiasm and political will—important outcomes and essential implementation tools.

Courtesy of Goody Clancy

Placemaking often results from the creative work of an individual urban designer, but, rather than an abstract process, every step toward its realization should be informed by and shared with the larger community through the engagement process. The best urban designers understand that the many levels of community input—design preferences identified through visual surveys, design workshops that address the tough issues of height and massing or street design, guidance on trade-offs between alternatives like massing or locating particular uses—don’t replace individual creativity; they enrich it. They ground it in the realities of people and place. The community owns the needs and aspirations that should inspire the plan, and it is critical that they feel ownership of the results.

Later in the process

Create an urban design plan

Translate the vision into urban design that connects principles to proposals and proposals to implementation. The kind of guidance needed and the intended audiences should drive a plan’s form, content, and level of detail. Plans often address multiple audiences—residents, advocates for specific issues, elected officials, developers, property owners, institutions—which means they need to respond to multiple agendas. Those might include the basis for new zoning, a call for developer proposals; implementation of a regional smart-growth strategy; creation of an innovation district; and/or the encouragement of community interest in an environmental initiative.

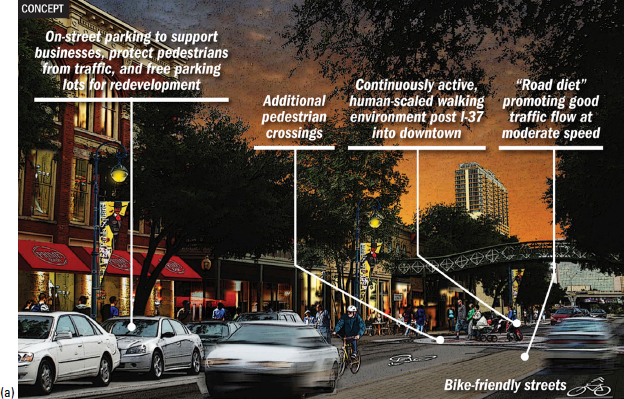

6.12 a, b Sunset Station District Charrette, for the Zachary Companies, San Antonio. Demonstrating the direct connection between later proposals and the values articulated by participants in the vision process can help stakeholders see their input in the urban design concepts that emerge.

Courtesy of Goody Clancy

The product generally takes the form of a report, online or in print, and usually involves drawings; three-dimensional computer models; fly-through computer animations; presentation materials for public meetings; and websites, posters, or other communication tools.

Engage partners

As the plan takes shape, engage city, businesses, developers, and other potential partners in attaching specific implementation strategies to every recommendation to ensure that the vision is achievable. Have both residents and elected officials agreed to the idea of new zoning? Do developers believe that potential private-sector development—and associated community benefits—are feasible? Does the transportation department support reduced parking ratios? Is a local institution or bank willing to set up a revolving community investment fund? Getting answers to such questions doesn’t represent cutting backroom deals but rather a public and transparent effort to ensure that the plan will adhere to the community’s vision.

Report to the community

Never deliver a plan without fanfare. Publicizing the thinking behind the vision, the vision itself, and how it will be achieved is an important component of implementation—as well as a civic responsibility. The larger community not involved in the urban design process should understand the plan and their stake in its success. No plan—or study area or concern such as sustainability or economic development—exists in isolation. Every plan deserves to be understood, and embraced, as part of the larger and continuous process of community building.

Next steps

Without champions committed to seeing it carried out, an urban design plan can easily end up on a shelf. The process will have involved collaboration among multiple members of the community, professionals, and public officials. Each of these groups will now play an important role in implementing the plan, and a key function of any plan should be to identify them.