Chapter 5. You Already Know How

If you think that creating a story map is complicated, or mystical, or in any way hard to do, let me assure you right now that it’s not. In fact, you’re already wired to understand all the basic concepts used to create a map. Let’s work through an example right now, taken from everyday life. And, to make it simple, we’ll use your life. Along the way I’ll give some names to those important concepts you already understand.

Grab a pad of sticky notes and a pen, and follow along with me. Don’t worry—take your time. I’ll wait.

Ready?

1. Write Out Your Story a Step at a Time

Close your eyes, and think back to the moment you woke up this morning. You did wake up this morning, right? What’s the first thing you recall doing? Now, open your eyes, and write it down on a sticky note. I’ll write along with you. My first sticky note says, “Hit snooze.” Unfortunately, it usually does. On bad mornings I may have to hit it two or three times.

Now, peel off that sticky and put it on the table in front of you. Then, think of the next thing you did. Got it? Now, write it on the next sticky, peel it off, and place it next to the first one. Then keep going. My next couple of stickies say, “Turn off alarm” and “Stumble to the bathroom.”

Keep writing sticky notes until you’ve gotten ready for work, or whatever you’re doing today. I usually end with “Get into my car” to start my drive for work. I expect it’ll take you three or four minutes to write all your stickies.

Tasks Are What We Do

Take a look at all the sticky notes you wrote. Notice how all of them start with a verb? Well, almost all of them. These short verb phrases like “Take a shower” and “Brush teeth” are tasks, which just means something we do in order to reach a goal. When we describe the tasks people using our software do in order to reach their goals, we’ll call them user tasks. It’s the most important concept to building good story maps—not to mention writing and telling good stories. You’ll find that almost all the sticky notes in story maps about what people do using your software use these short verb phrases.

Now stop here for a minute and think about how easy that was. I asked you to write down what you did, and naturally out of your brain tasks came out. I think it’s pretty cool that the most important concept is the most natural.

Don’t get too hung up on that word task. If you’re a project manager, you’ve noticed project plans are full of tasks. If you’ve been using stories in Agile development, you know that planning work involves writing a bunch of development and testing tasks. If you’re neither a project manager nor a software developer, watch out when you use the word task because those other people might think you mean the kind of tasks they usually think about, and they’ll tell you you’re using it wrong.

User tasks are the basic building blocks of a story map.

Now, count the number of tasks you wrote down.

Most people write somewhere between 15 and 25. If you wrote more, that’s fabulous. If you wrote less, man, you’ve got a simple life. I wish I could get ready in the morning that quickly. But you may want to look back at your list and see if there’s anything you skipped writing down.

My Tasks Are Different Than Yours

I’m sure this doesn’t come as a surprise to you, but people are different from one another. You’ll see these differences expressed in the way they choose to do things.

For instance, some people have both the motivation and self-discipline to exercise almost every morning. If you wrote a couple of tasks related to exercise, you rock! I’m still working on that myself.

Some people simply have more responsibilities because of the household they live in. If you’ve got kids, I promise you wrote down several tasks that people without kids didn’t. If you have a dog, you may have a task or two dedicated to taking care of the dog.

Keep that in mind when you’re thinking about people using your software. They may have different goals when using it. They may use it in different contexts that force them to take into account other people or things.

I’m Just More Detail-Oriented

In this exercise, some people just write a lot more details than others. They might take something like “Make breakfast” and instead write “Put bread in the toaster,” “Pour a glass of juice,” or, if you’re my wife, “Add kale to the smoothie,” which is one of the tasks I really hate her doing.

Tasks are like rocks. If you take a big rock and hit it with a hammer, it’ll break into a bunch of smaller ones. Those smaller rocks are still rocks. It’s the same thing with tasks. Now I don’t know when a rock is big enough to be called a boulder, or small enough to be called a pebble, but there’s a cool way to tell a big task from a small task.

My friend Alistair Cockburn described the goal level concept in his book Writing Effective Use Cases (Addison-Wesley Professional). Don’t worry, we’re not going to start writing use cases. It’s just that the concept is really useful when we’re talking about human behavior.

Alistair uses an altitude metaphor where sea level is in the middle, and everything else is either above or below sea level. A sea-level task is one we’d expect to complete before intentionally stopping to do something else. Did you write “Take a shower” in your list of tasks? That’s a sea-level task because you don’t get halfway through your shower and think, Man, this shower is dragging on. I think I’ll grab a cup of coffee and finish this shower later. Alistair calls these functional-level tasks and annotates them with a little ocean wave. But I’ll just call them tasks.

Tasks like “Take a shower” break down into lots of smaller subtasks like “Adjust water temperature” and “Wash hair,” and, if you’re my wife, something involving an exfoliating loofah thing. Remember, people are different, and you’ll see behavior differences in the way they approach tasks. Alistair annotates these with a little fish because they’re below the ocean.

Finally, we could roll up a bunch of tasks into a summary-level task. Taking a shower, shaving, brushing teeth, and all that other stuff you do in the morning after you get out of bed could roll up into a summary task. I’m not sure what I’d call it, though. “Getting cleaned up?” “Morning ablutions?” Ablutions is a silly word. Don’t use that.

Use the goal-level concept to help you aggregate small tasks or decompose large tasks.

2. Organize Your Story

If you haven’t done this already, organize your tasks in a left-to-right flow with what you did first on the left, and what you did later on the right.

Try telling a story by pointing at the first sticky note and saying, “First I did this,” and then pointing to the next sticky and saying, “then, I did this.” Now keep going moving from left to right and telling your story. You can see that each sticky note is a step, and hidden in between each sticky note is the nifty little conjunction phrase “…and then I…”

I’ll call this left-to-right order the narrative flow, which is a fancy way of saying “storytelling order.” We’ll call this whole thing a map and that narrative flow is its left-to-right axis.

Wow, my flow got pretty wide. I started stacking things that happen in and around the same time. As I lay out the flow, I see I already missed a few details, and I’m trying to decide if they matter.

Maps are organized left-to-right using a narrative flow: the order in which you’d tell the story.

Fill in Missing Details

The cool thing about this arrangement of sticky notes is that it allows us to see the whole big story. Seeing the story organized in a narrative flow allows you to more easily see the parts of the story that are missing.

Look back at your growing map and look for steps you might have missed.

I added just a few more. There’s lots of details that are below sea level that I’ve decided to not write down. If I did, there’d be hundreds of stickies.

3. Explore Alternative Stories

So far this is dead obvious, right? Learning this was hardly worth the paper you’re wasting. But wait, it’s about to get interesting.

Take a minute and think about what you did yesterday morning. If there are different things you did yesterday morning than you did this morning, write them down and add them to your map.

Think of mornings when things went wrong. What if there was no hot water? What did you do then? What if you were out of milk or cereal or whatever you normally eat for breakfast? What if your daughter flew into a panic because she forgot to do her homework that’s due today, which is what happens in my house every once in a while. Then what? Write tasks for what you’d do and add them to the map.

Now, think about your ideal morning. What would make your morning perfect? For me, it would be getting some exercise and enjoying a long breakfast while I catch up on some reading. But then I’d have to get up a lot earlier and stop hitting snooze.

Notice also that you’ll want to put some tasks in a column, both to save space and because they seem similar to other tasks you might normally do. For example, you might find that you’ve got tasks for making a really great breakfast that you can put in a column along with the tasks for making the quick breakfast you normally make.

My friend David Hussman calls this “playing What-About,” a phrase you might remember from Chapter 2 and Chapter 3. Unfortunately, we could play What-About for a long time and make this map huge. I added a few more things to my map specifically for things I wish I’d done, like exercising or doing a bit of relaxing reading during breakfast. I also added a few more common alternatives that often happen in the morning.

Details, alternatives, variations, and exceptions fill in the body of a map.

Keep the Flow

Notice that when you start to add these new tasks, you’ll likely have to reorganize your narrative flow. I know I did. For instance, I’d need to slip that exercise thing in between getting up and taking a shower. And I’d have to add in “Put on exercise clothes,” which isn’t the same as the “Get dressed” step after taking a shower.

If you relax and put things where it seems natural, you’ll find a narrative flow that feels right. When you tell your story now, you’ll find that you can tell it a bunch of different ways. You can tell the typical day story, the fabulous day story, and the story that has an emergency or two—all by pointing at different stickies as you talk through it from left to right. Try using some other conjunctions to glue your tasks together. You might say, “I usually do this, but sometimes I do this” or “I do this, or this, and then this.” (I’m expecting you to fill in the word this with what you actually do, because I can’t see what you’re pointing at from here.)

When I was a kid, there was a popular series of children’s books called Choose Your Own Adventure. Maybe you remember them. The idea was that you’d read to the end of a section and then be given a couple of choices about what the hero of the story would do next. After each choice was a page number. Once you made your choice, you would turn to that page and continue reading the story from there. Truthfully, I was never a fan of those books. I always seemed to end up at the same place no matter what choice I made; there never seemed to be enough choices to make a really great adventure. The map works a little like that, except better. The number of ways through a map is almost limitless—which, if you’re thinking about the way real people might use a software product to meet their goals, is actually pretty accurate.

If you want to make things really challenging, do this exercise with a couple of people you work with. You’ll learn more than you ever wanted to know about the people you work with, and you’ll have a bit of fun finding a narrative flow everyone agrees on. By “fun,” I mean “argument.” There are always people who eat breakfast before showering, and some who eat after. There’s the great tooth-brushing debate—do you brush before or after breakfast, or both?

Relax.

If you’re arguing, it likely means that it doesn’t matter. For instance, putting breakfast before or after taking a shower is a matter of preference. Go with what’s most common for the group you’re working with. You’ll find people won’t argue about things that do matter. For example, putting “Get dressed” after “Take a shower” isn’t just a matter of preference. Doing it the other way around results in showing up to work wearing wet clothes.

4. Distill Your Map to Make a Backbone

By now, your map should be looking pretty wide, and if you’ve explored lots of options, maybe a little deep. It’ll likely have 30 or more tasks. It should look like the spine and ribs of a weird animal.

If you step back a bit and look across your map from left to right, you’ll find there are bunches of stories that seem to go together—for instance, all those things you do in the bathroom to get ready, or all those things in the kitchen to make breakfast, or that junk you do to check the weather, grab a coat, and load your bag with your laptop or other stuff you’ll need before leaving the house. Can you see those clusters of tasks that seem to go together to help you reach a bigger goal?

Above each of these clusters of similar stickies, put a different colored sticky note. Write a short verb phrase on it that distills all the tasks underneath it.

If you don’t have a different color of sticky note, I’ll let you in on a secret. Every package of sticky notes comes with two shapes! Rotate a sticky note 45 degrees and, poof, you’ve got a cool diamond shape. Use that if you want to make a sticky look different.

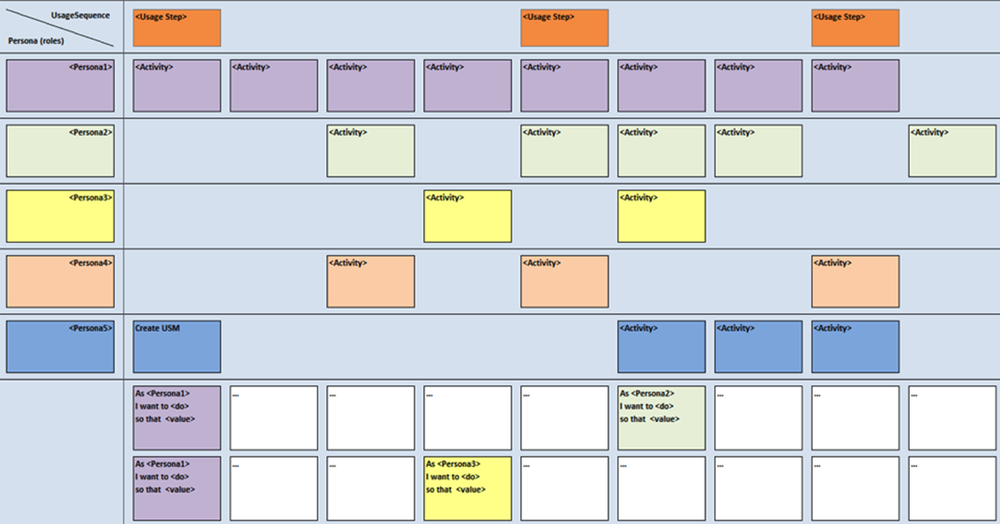

These sticky notes with a higher goal-level task are called activities. Activities organize a bunch of tasks done by similar people at similar times in order to reach a particular goal. When you read the activities across the top of the map, they’re in a narrative flow, too. The row of stickies is the backbone of the map. If you’ve got a map with lots of stickies in it and you wanted to share it, a good way to start is by telling a high-level story. Just read the backbone of the map, with the “…and then they…” conjunction between each activity.

Activities aggregate tasks directed at a common goal.

Here’s my growing map with activities added to give the map a backbone. It makes it easier to read and find things, at least for me. And it makes it easier to really get the big picture of what’s going on in my morning.

Activities and high-level tasks form the backbone of a story map.

Activities don’t seem to have common language the way tasks do. For instance, what do you call that thing you do before leaving the house? That thing where you gather up your bag, find a shopping list, check the weather, and grab an umbrella if you need it? I could call it “gathering up my junk.” You might call it something different.

When you build these for your products and your customers, you’ll want to call it what they call it.

5. Slice Out Tasks That Help You Reach a Specific Outcome

Now, here’s the really cool part—the part where you get to use the map to help you imagine something that didn’t happen.

If you look at the map you’ve built, you’ll probably see “Hit snooze” or “Turn off alarm” somewhere on the left edge. Imagine that this morning you can skip that one. You can skip it because last night you forgot to set your alarm. Your eyes shot open and looked at your clock and you saw you needed to be somewhere in just a few minutes. You’re really late! Don’t panic—we’re just pretending.

Write “Get out the door in a few minutes” on a sticky and place it to the left of the map near the top. Now, imagine a line slicing through the middle of the map left to right—kinda like a belt. Now, move all the tasks below that line if you wouldn’t do them to reach the goal of getting out in a few minutes. Don’t move the activities down, even if there are no tasks left under them. Having the activity with no tasks in it lets you show that you aren’t going to hit that goal this morning.

You’ll likely be left with just a few tasks in the top slice. Now go back through the flow and fill in tasks that are missing and that you would do if you were late. For example, you might normally take a shower, but when you’re late you instead add in tasks like “Splash water on face” or “Use a washcloth to wash the particularly stinky parts of my body.” When doing this activity with a group of developers, I often see the task “Apply extra deodorant.” I’m not judging. I’m just saying.

Here’s my map sliced to find the tasks I’ll need to get out the door in a few minutes.

You can try this trick by thinking of different goals to hang on the left side. Like “Have the most luxurious morning ever” or “Leave for a two-week vacation.” You’ll find the narrative flow stays pretty durable, but that you’ll need to add or remove tasks to help you reach that different goal.

Use slices to identify all the tasks and details relevant to a specific outcome.

That’s It! You’ve Learned All the Important Concepts

That was really easy, wasn’t it? As you built this map you learned that:

- Tasks are short verb phrases that describe what people do.

- Tasks have different goal levels.

- Tasks in a map are arranged in a left-to-right narrative flow.

- The depth of a map contains variations and alternative tasks.

- Tasks are organized by activities across the top of the map.

- Activities form the backbone of the map.

- You can slice the map to identify the tasks you’ll need to reach a specific outcome.

Do Try This at Home, or at Work

Now, I’m pretty sure a great number of you were just reading along and not really mapping as you read. Don’t think I didn’t notice. But if you’re one of those slackers who didn’t map your morning, promise me you will try it. It’s hands down my favorite way of teaching these basic mapping concepts. If you’re trying out mapping for the first time in your organization, get a small group of people together and run through this exercise. You’ll all learn the basics. And you’ll be well on your way to being able to map anything.

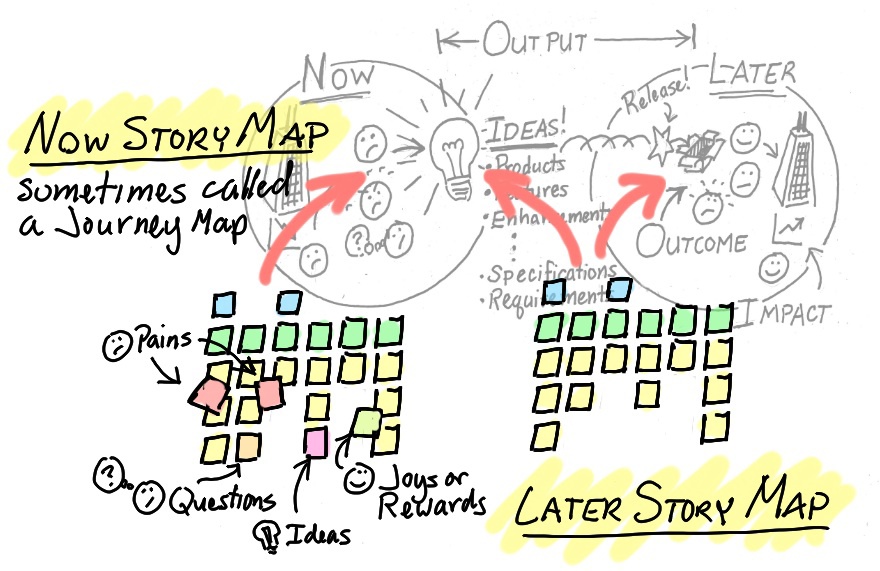

It’s a Now Map, Not a Later Map

I suspect a few of you caught this, but the map you just created has a fundamental difference from the maps created in the first four chapters. The maps Gary, Globo.com, Eric, and Mike and Aaron created all imagine how users will use their products in the future—later, after the product is delivered. They wrote tasks and activities that they imagined people doing in the product. But the map you created is a map about the way you do things now—this morning, as a matter of fact. And, as it turns out, the concepts are the same in both. So be relieved I haven’t wasted your time.

One of the cool things about “now story maps” is that you can build them to better understand how people work today. You just did this to learn how you got ready this morning. You can learn even more if you go back and add other things to the map. The easy things to add are:

- Pains

- Things that don’t work, parts people hate

- Joys or rewards

- The fun things, the things that make it worth doing

- Questions

- Why do people do this? What’s going on when they do?

- Ideas

- Things people could do, or that we could build that would take away pain, or make the joys even better

Lots of people in the user experience community have been building these for years to better understand their users. Sometimes they’re called journey maps, but they’re the same basic idea.

Try This for Real

In the early 2000s, I led a team at a small product company called Tomax. We built software for brick-and-mortar retailers—those shopping places we used to go to before spending all our time online. We’d taken on a new customer that ran a large chain of paint and interior decoration stores. Now, we knew quite a bit about retail—and about the users who sold things at point of sale and managed inventory—but there were some things we didn’t know that were specific to paint and decor stores. For instance, we didn’t know how to sell custom-tinted paint or custom blinds. And we had to learn fast.

To help us learn, we asked for the help of these three ladies. They’re not software people. They’re interior decorators working for the company that wanted our software. From them we learned the ins and outs of selling custom blinds. So that we could learn quickly, we asked them to think back to the last time they sold custom blinds. We asked them to write down everything they did—from the moment a customer contacted them, until the moment the blinds were installed and their customer was happy. Now that should sound familiar, because we asked them to do the same thing you just did to map your morning—and it went pretty much the same way. They could name what they did to sell custom blinds as easily as you could name what you did to get ready in the morning. And, when we organized their tasks, we all learned that there wasn’t any one way to do things, that they each did things differently or in a different order. You’ll see the same thing if you try the getting-up-in-the-morning map with a small group of different people.

From this simple storytelling and mapping activity, we all built shared understanding of how they worked now. It was from here that we could begin to translate this map into the things they’d need to do in the software we’d create later.

With Software It’s Harder

I won’t lie to you. If you’re a software professional, it may take you a while to stop talking about features and screens, and to start writing short verb phrases that say what people are really trying to do. Keep practicing. You’ll get it.

This will be really hard if you don’t know exactly who your user is, what she’s trying to accomplish, or how she goes about it. Sadly, trying to build a map in this situation will just point out what you don’t know. If that’s where you are, then you’ll need to learn more about people and what they do. Better yet, work with them directly to create a map.

The Map Is Just the Beginning

Building a map helps you see the big picture, to see the forest for the trees. That’s one of the biggest benefits of story mapping. But if you’re the one responsible for building the forest, you’ll need to do it one tree at a time. You’ve already learned the two most important things that make stories work:

- Use storytelling with words and pictures to build shared understanding.

- Don’t just talk about what to build: talk about who will use it and why so you can minimize output and maximize outcome.

Keep these things in mind, and everything will fall into place as you go forward.

It’s time we talked about some of the tactics for using stories “tree by tree,” because a lot can go wrong, and there are a few more things you need to know to use stories well.

[8] Cover Story is one of the many great practices found in the book Gamestorming by Dave Gray, et al. (O’Reilly).