Chapter 7

Make a Film in VR from Start to Finish

This chapter provides step-by-step instructions for making a narrative live-action VR film. A similar structure can be used for both live broadcast and documentaries; simply omit the irrelevant steps.

Development

Screenwriting for VR

When CinemaScope was invented in the 1950s, “Metropolis” director Fritz Lang mocked its super-wide aspect ratio and said, “Cinemascope is not for men, but for snakes and funerals” (in “Contempt,” dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1963). However, CinemaScope became incredibly successful and its anamorphic format has continued to this day. Similarly, one can wonder, what is VR good for, story-wise? Data gathered on the most-watched VR films show that the most successful genre is horror.

Anthony Batt, Co-Founder and Executive Vice President, Wevr

Storytelling will move from three-act narratives with cameras over their shoulder and cutaways, to a completely different form of immersed storytelling, simulation-based. You will be able to live the hero’s journey, the victim’s journey, etc. I can’t even explain what it’s going to be like because it’s so different. I can’t conceive it. But if we keep working and figuring out how to deliver really amazing, agency-rich, sim[ulation]-based content stories, then we’re opening up the opportunity for a new medium to emerge and to decide what that really, frankly is.

Robyn Tong Gray, Chief Content Officer and Co-Founder, Otherworld Interactive

“Sisters” is the first project we created at Otherworld. Personally I love horror movies – bad movies, good movies, I enjoy them all. It was nearly Halloween season and so the timing was ripe to play around with the horror genre. Until then, I’d only ever been a consumer of horror, never a creator.

Figure 7.1 “Sisters” – ©Otherworld Creative

In two weeks with a production team of three, we created “Sisters” and a few months later we polished it up a bit and released it. Since then, it’s been downloaded over 2.5 million times across mobile platforms and is our most popular experience. Something about the particular subsection of horror makes it accessible to everyone (kids, young adults, even moms), and it also, unintentionally, is a very social experience. People love playing it but they also really love watching (and filming!) others playing it.

A big part of indirect control is about getting players to react naturally to authored stimuli. A horror atmosphere calls for heightened awareness and responses. The spatial sound cue of a door opening in a café on a rainy day elicits a very different response than if the same sound cue is played against a dark and stormy haunted house.

It’s also just fun! I think there’s something about the horror genre that allows people to loosen up. The threat isn’t real, they can cede control and indulge in fear in a safe environment. When we craft horror experiences, we shoot for a specific subsection of horror – ghosts and creepy dolls and spooky atmospheres are fair game, intense blood and gore and hyper-realistic visuals are not. We aim for that level of fun horror, and work to create a visual and audio style that complements the story but also leaves plenty of room to remind the player it isn’t the real world.

I think as creators in VR we have a responsibility to our audience to take care of them, and with genres like horror we have to remember that VR really is intense. It really can feel like you’re there and the experience we give our audience in VR creates memories much more akin to real-world experiences than any stories we might tell on a 2D screen or on paper.

Shari Frilot, Founder/Chief Curator of New Frontier at Sundance Film Festival

I think people get excited about VR and excited about the feelings that it creates because it engages with your biochemistry. What makes you laugh, what makes you cry, that’s biochemistry. Not only does VR do that, but it engages with your sense of place, where your body is, and that engages your survival instincts, what makes you live or die, what helps you instinctually avoid the bullet, avoid the tree that’s falling, and that’s something that you don’t get so much in a theater. You always know you’re in a theater, even though you’re losing it in a tragedy or a horror story. You always know that you’re in the safety of that theater. When you’re in the VR headset, you don’t know that. You really don’t. You have to remind yourself that you’re not actually in the situation that you perceive when you’re in a VR experience.

Horror is one of the easiest genres to play with in VR. It is very visceral and that makes it really easy to evoke player response. With horror movies and even video games, there is a safety net – players can only see this curated, two-dimensional framing contained within their screen. In VR the safety of the 2D screen has been removed and they are forced to start literally looking over their shoulder.

Certain genres are indeed more successful in VR than others. However, VR opens up a lot of opportunity for all genres and all stories as long as its immersive factor is taken into account and the storytellers use the power of presence to their advantage.

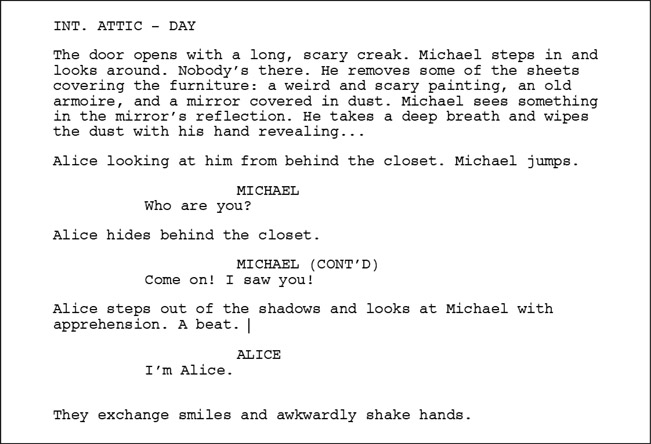

When it comes to screenwriting, it can be difficult to describe the newly acquired 360° space using the traditional script format. For example, see Figure 7.2.

What is happening and where? How do you indicate what the point of interest is? Traditional formatting is optimized for describing actions and characters that fall within the edges of a rectangular frame. Things can become very confusing when multiple actions are happening at the same time in different zones of the sphere. Given the inadequacies, try dividing the four main quadrants of the sphere into different columns.

In the example in Figure 7.3, the POI is highlighted allowing the reader to understand how the 360° sphere is utilized. However, this formatting is time-consuming and can be tedious.

Another method is to use a type of formatting that is sometimes used for commercials.

No matter which format the writer decides to use, the entirety of the 360° sphere should be described at the beginning of each new scene to help readers get situated. For this, I recommend the use of the “clock position system,” as described in Chapter 6 (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.2 Traditional script formatting

Richard L. Davis, Screenwriter

There is a tradition in screenwriting that the length of a description of an action or dialogue on the page roughly equates to how much time it takes up on screen. This is how the guideline “one minute per page” came to be. Writing in VR, there are several actions going on simultaneously, several points of interest that should reinforce the theme or build out the world. Settings, the reality around the viewer, can be described at length, sometimes taking up a quarter of a page. Time described is simultaneous, but the page is sequential. Some pages are three minutes, others are 30 seconds. “One minute per page” is out the window – positively defenestrated!

Figure 7.4 Commercial script formatting

Jessica Kantor, VR Director, “Ashes”

The biggest learning is to design an experience within your budget. I’ve found it far more effective to experience something simple but beautifully executed then something beyond the scope of the team which risks the participants escaping the experience emotionally. For example, camera movements without proper stabilization, or reasoning that makes sense to the participants’ brains. The intense feeling of nausea instantly drives participants to take off the headsets and can even keep them from putting on a headset in the future. It is also really expensive in post to clean up the artifacts from a moving camera, so if the budget doesn’t allow for that to happen properly, I’d recommend redesigning the concept.

Budgeting/Scheduling

When it is time to start working on the budget of a VR experience, a lot of producers have the same questions: Is it more expensive to shoot VR than traditional film? Is it slower? How big should my crew be? These are all important questions, but the answers depend first and foremost on the creative. A line producer who has experience in virtual reality can help you adapt your generic budget to VR.

In general, shooting live-action VR can be faster than shooting traditional film. This is due to the fact that we tend to do fewer shots and less coverage in VR. Also, the lighting is often limited to practicals and the camera to static shots. On the other hand, the entirety of the 360° sphere must be dressed and staged, and long scenes require a lot of rehearsals (which are not usually scheduled on expensive shooting days). Long scenes (5–10 minutes) can take anywhere between a half to a full day to film, while shorter scenes can be done in a matter of hours. On a standard film production, you can expect to shoot about five pages of script per day, which usually equates to five minutes of final product footage. The average on VR sets is closer to 5–8 minutes a day. Again, this depends on the story, number of actors, locations, etc. For example, “Marriage Equality VR,” a seven-minute single shot, was filmed in just one day.

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

In the case of “Miyubi,” we did about 12 shots total for a running length of close to 40 minutes. If you do the math, that’s an average of about three minutes per shot. Some are a little shorter, some are a little longer. We did four days of principal photography with about two shots a day. Then we shot one scene in Cuba and we shot one scene in LA, so a total of six shooting days.

In terms of crew sizes, VR crews are usually smaller than traditional film crews. The camera, electrics, and grip departments are the ones that will be the most different, due to the reasons explained above: little-to-no camera movement, practical lighting, etc. In the case of a VR shoot using the “nodal” technique, the crew is often the same as on a regular shoot, as non-VR cameras and lights are required.

When it comes to budget itself, there is usually only one additional line item specific to VR: stitching. Everything else remains similar to a “normal” budget. Stitching price varies greatly depending on the resolution, whether it’s 2D or 3D, and the quality of the stitch itself. As the technology progresses and automatic stitching algorithms are developed, costs will go down. As of 2017, good stitching services for stereoscopic content can top at US$10,000 per minute.

It is important to note that these budget caveats do not necessarily apply for game engine-only VR experiences. A line producer with extensive experience in gaming budgeting should be considered for those projects.

Steve Schklair, Founder, 3ality Technica and 3mersiv

If you’re using a GoPro setup, two or three people can go out and make a project. There is a camera person, a sound person, and a director-type person. A lot of 360° content is shot that way, especially documentaries. Some of the more dramatic narrative material where there is extensive lighting or VFX, then you may have normal-size crews as if it were a film. A small independent film has a very small crew and a large feature film has a very large crew, so it really depends on the scale of the 360° piece you’re shooting. The camera department is taking a big hit. You don’t have focus pullers, you don’t have operators. You’ve got somebody handling the camera so you can call them the first AC (assistant camera). They’re not pulling focus, they’re keeping the dirt off the lenses. They’re helping the engineer plug everything together. In a professional world you need an engineer and camera technicians. On bigger shoots you might bring in a secondary engineer to handle the recording.

Ryan Horrigan, Chief Content Officer, Felix & Paul

Currently non-gaming VR content is often much cheaper (live-action 3D 360° video) than cable television content on a cost-per-minute basis. Animated VR content, however, can cost considerably more to produce than live-action VR content, but is still quite low on a cost-per-minute basis compared to feature film animation. I do believe there is a sweet spot for cost per minute for content being released in the near term, but as the user base across platforms doubles, triples, and eventually quadruples, budgets can and will increase to more closely reflect the cost-per-minute budgets of cable TV series. If VR/MR content someday becomes the most widely consumed content and film, and TV becomes secondary, then we expect VR/MR production budgets to rise as a reflection of the global audience size.

Financing

The million-dollar question is how to finance VR experiences when audiences are still small and limited to early adopters.

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

Most of the projects we’ve made to-date were in partnership with one of the platforms or studios, and without any hope of making money from sales as of today. The platforms really want there to be content. Some have a lot of faith in 360° filmmaking; some are more focused on computer-generated, interactive, positional VR. I think you can make a pretty ambitious project today and have it funded by one of these platforms if you have a good track record. That’s going to shift in the next two years, when you should be able to sell a piece to the public and make money that way.

The way I see it, there will definitely be fewer headsets out there than there are people with smartphones and TVs. However, there will also be less content. If you make a good piece of content, you are not competing against many others, like in TV or in film.

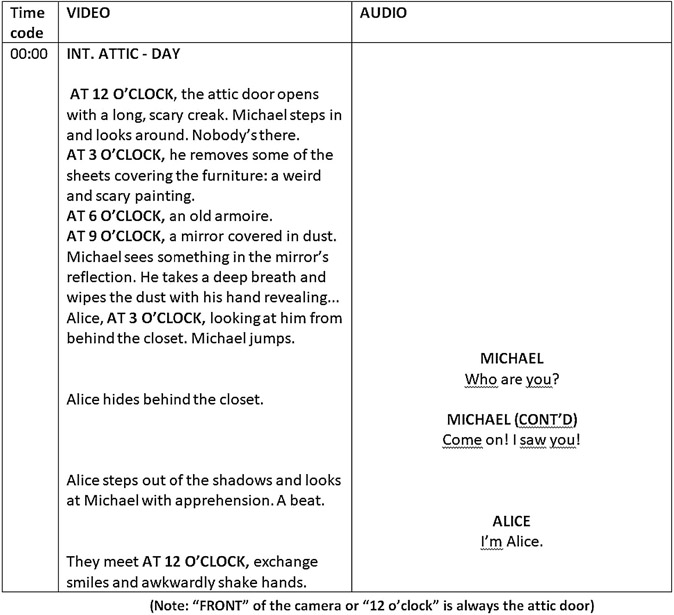

Figure 7.5 “My Brother’s Keeper” ©PBS

Ryan Horrigan, Chief Content Officer, Felix & Paul

It’s our belief that there is one segment of the content market currently missing, which will come to fruition in the next few years and may actually drive the largest majority of user adoption. This type of content, in our opinion, is original premium content, perhaps episodic and serialized, in both fiction and non-fiction: VR native stories that can only exist in VR in the way that these stories are told, thus proving the industry’s assertion that this is an entirely new storytelling medium. In other words, stories that could just as easily be films or TV shows in the way in which they’re told don’t need to be produced in VR and won’t help drive viewership ultimately. As original VR native content emerges, the feeling may be reminiscent of the early days of cable and premium cable, where it took original IP [intellectual property], never before seen in film or on network TV, to give consumers a reason to care (“The Sopranos,” “The Shield,” etc).

The VR technology is still in its infancy, as is its business model. Investors have yet to understand fully how best to monetize VR content. As of today, most of the high-end VR content is either branded or created as companion pieces for big intellectual property tent poles. In this case, the project’s financing usually comes from a separate marketing budget. Marketers and publicity people are very keen to produce engaging VR content as it is perceived as new and exciting. Partnering in these situations offers VR filmmakers the opportunity to tell beautiful stories with a decent budget. For example, “My Brother’s Keeper” is a story-driven VR re-enactment of the Battle of Antietam from PBS Digital. The experience is a companion piece to PBS’ primetime Civil War series, “Mercy Street.”

Other financing opportunities include grants from organizations such as the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), the CNC in France, Oculus (the “VR For Good” initiative, the “Oculus Launchpad” scholarship), HTC Vive (“VR For Impact”), etc. As the VR market develops and profits are realized, financing opportunities will increase accordingly and the process of developing VR experiences will become easier. Other interesting avenues are Google Daydream, PlayStation VR, Amazon, Hulu, Youku, Tencent Video, IQIYI, Fox, Sony, and Disney, which are all currently financing and/or buying virtual reality content.

Pre-Production

Cast and Crew

When the time has come to hire your crew and cast your actors/actresses for your VR project, a few things differ from traditional pre-production. First, it is important to hire a VR supervisor (it can be a director of photography who has experience in VR) as soon as pre-production starts so that he/she can advise both the director and the director of photography before the story-boards or the shot list is finalized. He/she then helps them to choose suitable VR equipment according to their needs and budget. Do not forget that the most important crea-tive aspects of VR are decided in pre-production: artistic and narrative discussions, shot lists, storyboards, and so on.

When it comes to casting, it can be wise to look for actors and actresses who have extensive experience in theater or improvisation.

There is an ongoing debate regarding whether a director of photography is needed or not when shooting VR. It is true that part of the DP’s responsibility is to select lenses and help design shots, which involves framing, camera movement, and depth of field, which do not apply when shooting 360°. The cinematographer’s job is to interpret a script and that is done through photographic tools. Those tools are lighting, filtration, lens choice, depth of field, etc. In VR, it is really a director’s decision on where he/she wants to stage the action and the camera.

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

Virtual reality is much closer to theater than cinema, so when we were casting, we were looking for people who have experience in theater. If they don’t, then we test them with scenes with long dialogue and improvisation. If another actor drops the ball, you need to be good at picking it back up because a long take will never be perfect unless you can spend weeks rehearsing it like you do in theater, and very few films have that luxury. I would say that none of the scenes we shot were what we had written because stuff happens. We have some scenes that have six or seven actors and they’re all interacting and moving around and talking to each other. It never exactly turns out how it was written; someone will skip a line or forget a line or say a different word so it has to be very organic and everyone needs to be working together. It’s also really fun and beautiful to see. The fact that none of the takes are perfect brings a bit of that into it as well. The happy accidents.

However, others argue that the cinematographer in a VR project is almost the same as traditional filmmaking in the sense of being the visual storyteller for the director and helping get his/her vision across within this 360° space. There is also an added layer of technical understanding that is a bit more than just knowing the camera; it is understanding all of the elements that go into creating a VR project.

Scouting Locations

The importance of location and world building are described at length in Chapter 6. It is useful to scout potential locations with these elements in mind, and to take photos in 360° (using, for example, the Ricoh Theta or Samsung Gear 360). Viewing these photos in a headset can help determine whether a location is “360° ready” or not.

Eve Cohen, Director of Photography, “The Visitor VR”

I find myself on VR projects needing to know more technically than I would have before. But I’m hoping that it gets to a point where I can actually just be a cinematographer the way that I feel like I’m the best version of myself, which is just to help get the vision of the director across onto the screen, or onto the sphere.

As a DP, I have a lot of conversations with the director about how we’re going to guide the story. It’s not so much about working with the director to just make a frame anymore. The DP really works with the director to help guide this story visually. They’re guiding the actors and they’re guiding the live action that’s happening around the camera. But as a cinematographer, you’re really in control of the entire sphere and the images and the way that people are looking. For example, if an actor is crossing left to right, are they going to be moving from a shadowy side of the world to a brighter side of the world? Or maybe as they’re walking to the right that’s going to be a cut point. And the next edit that we get to, what is that frame going to look like? And how are we going to fade into that one, using lighting perhaps?

There are documentary projects and television projects that say you don’t need a cinematographer also. And if that’s the kind of project you’re making where you don’t want that role to exist, you have to know what it is that you’re missing.

When it comes to VR, if you’re on a project that requires a very small crew and your director is skilled enough to also operate a camera and train their brain to think the way a DP does, then maybe you don’t need one. But just because it’s VR doesn’t mean you don’t need that creative collaborator who is going to be able to, say, let the director really do what they need to do, and then get all of the cameras, and all of the operators, and tech[nician]s, and really oversee the camera process. And if you just have a tech person who’s working on the camera, they’re not necessarily trained in the creative visual collaboration that goes along with making really great projects. I think a DP is really essential. I think it’s always great to have a collaborator in anything that you do, and you have another brain to make the film even better.

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

For “Miyubi,” the film is set in 1982 and takes place in a house. We decided to find a real house and re-did the decoration of almost every room in the house.

People who were there on the day of the shoot thought, “How did you find a house that still looks like it was stuck in the 1980s?” There was very little that seemed fake. In VR, the camera ultimately becomes a person, and you really need to be able to convince the viewers they are there for real as well.

Figure 7.6 “Miyubi” ©Felix & Paul Studios

Rehearsals

If the director and the camera crew have not shot VR before, extensive tests and training are strongly recom-mended. The crew must learn the new language of VR and be prepared to face any technical and narrative challenges before the first shoot day.

When rehearsing, the director should position him/herself where the VR camera will be, thus enabling him/her to fine-tune the blocking in the 360° space.

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

Once we have the location, we would adapt our staging diagrams and then start rehearsals with the actors, but these rehearsals were not done on location. For “Miyubi,” we did rehearsals in Montreal first, while our actual location was outside of Montreal, about an hour away. We discovered a lot of things and adapted our staging accordingly. Then we had rehearsals on location, and finally a couple more the day we were shooting. In total, we had three sessions of rehearsals.

Play with different heights for the camera and different staging until the scene feels organic and flows naturally. This process can also help the actors/actresses to understand that the VR camera is indeed the head of the participant and adjust their behavior accordingly.

Storyboard and Previz

Richard L. Davis, Screenwriter

The next generation of screenwriting software should directly incorporate elements of previz. This new kind of screenwriting software might look like a simplified game engine or a markdown language that compiles into an environment using a standard collection of objects and actors. Whether a writer is creating on a flat screen or directly in a virtual environment, the writer should have the ability to directly associate action and dialogue with a mock-up scene.

Figure 7.7 “Tilt Brush” VR app by Google

Richard Davis evokes the possibility of building a VR script within a game engine itself. This can very soon become a reality thanks to software such as Mindshow, which makes the process of creating stories in VR simple and accessible. One can also use VR apps such as Google’s Tilt Brush and Quill (for HTC Vive and Oculus, respectively), to draw storyboards in VR and in three dimensions.

You can also use Unity or Unreal to build a VR app that serves as a previz. This may seem overly complicated, but it can be a powerful asset when raising money for the final project.

Production

A Day on a VR Set

You made it! You have successfully written your VR project, raised money, and hired the best VR crew and great actors/actresses. It is now shooting day one.

Shooting virtual reality is very different from shooting traditional cinematography. First, there’s no behind-the-camera. There are a lot of things to consider in that: the amount of crew you have, where they are going to hide, not being able to have lighting rigs and a huge amount of equipment around because you are either going to have to come up with a really tricky way of replacing or removing it, or you are going to have to tear it down and light organically.

It impacts the way one lights and designs a scene, as well as how the set is run (where do you hide the video village? Crafty?). However, more importantly, it changes the relationship between the director and the actors/actresses, who often find themselves alone with the camera when it comes time to roll.

Some of the current VR solutions do not have live VR monitoring. Therefore, the director and the rest of the creative team must find ways to look at the takes without being seen by the camera. Sometimes one person can sit right underneath the camera if it is not moving. Another possibility is to be in the same room with the smallest footprint possible and to shoot a plate that will replace this portion of the sphere in post-production. Of course, this add-on comes at a cost.

Another option is to use an additional small VR camera which can broadcast live, such as the Samsung Gear 360 or the Teradek Sphere system (see Chapter 2 for more details about VR cameras).

Maxwell Planck, Founder, Oculus Story Studio, Producer, “Dear Angelica,” “Henry”

We’ve found it is helpful to storyboard out an idea, but it is dangerous to spend a lot of time discovering story in this process. It can be misleading to feel good about storyboards or 2D animatics when you’ll discover that the same story and pacing feels wrong when adapted to VR.

It is better to quickly move to one of the three previz techniques we’ve used over the course of making “Lost,” “Henry,” and “Dear Angelica.”

The first technique is to use a radio play. By crafting a paced audio experience that’s decoupled from visuals, it’s easier to close your eyes and imagine how an immersive experience could emerge from a radio play. We feel like you get better signal on having a good radio play turning into a good VR experience.

The second technique is from game development and it’s called gray boxing. Similar to how a story layout department works in computer animation, gray boxing is the work of creating rough blocking of the story and interaction mechanics by using simple shapes and stand-in characters. It’s a great way to iterate quickly, but it’s sometimes hard to project how ugly proxy sets and characters will turn into an experience that will feel good. I believe with time, as we see more projects from beginning to end, we’ll have more confidence to project how interesting ideas presented as gray stand-ins will eventually turn into a compelling experience.

The third technique we’ve just started working with is to have an immersive theater acting troupe workshop a script, and then over the course of several days, act out the experience with our director acting as the visitor. We can record the experience through several “playthroughs” and use that coverage to edit together a blueprint of what we would build in the game engine.

In the example shown in Figure 7.9, the VR camera is a Google Odyssey but you will notice that a small Samsung Gear 360 was also attached to the rover to deliver live VR monitoring to the director and the clients. The operator wears a McDonald’s costume, which allows her to pilot the rover while blending into the frame.

Randal Kleiser, Director, “Grease,” “Defrost”

The fact that the crew is isolated from the shooting experience is a bit of a drag for them. In “Defrost,” I cast myself as a character so that I’d be on the set and able to watch and direct the actors. It isn’t easy to muster-up enthusiasm for the day’s work when the crew is in the dark.

I played a wheelchair nurse pushing the viewer along … so I was able to fulfill a longtime wish of being a dolly grip. By being behind the viewer, I knew that not many of them would turn around and watch me, but I had to mask any reactions to the performances, which was not easy.

Figure 7.8 Randal Kleiser on set of “Defrost VR”

Paul Raphaël, Co-Founder/Creative Director, Felix & Paul Studios

In one of the last scenes of “Miyubi,” there’s a remote-controlled robot and the “puppeteer” had to be in the room to see it. He was therefore in the frame and I think (co-director) Felix probably was there, too, in an angle where very little action happened. I think even the sound guy was there. It was one of the scenes that we shot where there were the most people in the shot that weren’t supposed to be there. Sometimes it’s more complicated like, for example, when we were shooting “Sea Gypsies” in Borneo on the open sea, then often we’re on a boat that’s far enough that you can’t really tell that it’s a crew with people watching monitors on it.

Felix and I will also be there for the first few rehearsals on set and then we will split, with Felix staying close to the camera and me going behind the monitors where we basically have a combination of a 360° unfolded view and a security cam-style version of the scene. The person who stays next to the camera has to be very close to the camera or somewhere that’s a dead angle. VR is the perfect medium to be two directors because there’s so much going on in all directions. Felix and I have been working together for 12 years. The first seven or eight years of our career where we were making movies, we did it because there was a great synergy between us, but we were never using ourselves at full capacity. But then as soon as we started working in VR, it all made perfect sense. In some cases, we even brought on a third director. In the case of the Cirque du Soleil series we’ve been doing, we’re working with François Blouin who has a lot of experience with Cirque du Soleil and really knows the shorthand of the acrobats and the performers.

When shooting using the “nodal” technique, you do not have to worry about these issues, as parts of the sphere are shot separately using a normal camera.

When designing the shots, one must keep in mind the constraints inherent to the VR stitching process described in Chapter 2, and respect a minimum distance to the camera. Most of the current VR cameras can present stitching issues when objects or people come within 4–6 feet of the camera. It is vital to know the workflow well and make decisions regarding the minimum distance before the first day on set.

Figure 7.9 Celine Tricart on the set of “Building a Better McDonald’s, Just for You” – photo credit Benjamin Scott

Cinematography

Liddiard’s description of the work done on “Help” to select the right camera/lens setting and overcome challenges due to the nature of 360° filmmaking proves how technical VR is. An experienced VR DP or supervisor is a must, especially for ambitious projects such as “Help.”

However, VR is a challenging medium for directors of photography. Not only do most current VR cameras lack the same dynamic range and quality of professional film cameras, but they also provide limited choices of lenses and filtration.

In the case of documentaries, we usually rely on natural lighting, with the exception of interviews where we will do some lighting and then erase the lights. For narrative, we will almost always light a scene through a mixture of practicals, natural lighting, and lights that we paint out in post-production. The lights can either be up out of the way on the ceiling, which can be relatively easily plated, or somewhere in the frame that has the least amount of crossing. If the camera is moving, we often use a motion-controlled dolly for the camera, which can either be programmed or remote controlled. Depending on the surface you are on, you can get a relatively close-to-perfect repetition.

Gawain Liddiard, Creative Director, “Help,” The Mill

For “Help,” we used a RED Epic with a Canon 8-15 lens. We found that the geometry was really good. And the 8-15 we can set up in such a way that you are cropping slightly. We had the cameras mounted in portrait so that you had the 180° sweep vertically, but then not the full 480° horizontally, and that’s actually why we went with four cameras. If you had the 480° sweep, you could knock it down to three cameras, but we wanted that boost in resolution, so at that point, there’s the decision to go with four cameras versus three. And so by going with four, you can get a lot more resolution – it’s not just that you had an extra camera, it’s the fact that you can allow a larger coverage of your film back. The only issue with this lens is that it’s an F4 so we had to boost the ISO. We involved the guys from the R&D department at RED. Discussed all the settings that we could possibly tweak to push out as much noise as possible. With such a slow lens, you want to pump your environment full of light, but in the VR world, it’s a really hard thing to do. Any light you put in, you’re gonna have to paint it out. So it’s a real catch-22 if you want a lot of light, but where do you put those lights? And not just seeing the light, but something we’ve found in proof-of-concept tests that we did is the camera shadow is horrendous. You really have to dance around your camera shadow because it’s almost guaranteed that it’s going to ripple across an actor at one point. Obviously the camera shadow moves with the camera itself, so there’s no motion blur on your camera shadow and you get this horrendous, crisp, perfect image of your camera rippling across your scene that has to be taken out later on. So it was a big consideration and it was something we just had to accept, the fact that it was a relatively slow lens and another reason why we’re thankful that the RED camera has the range to sort of pull that up. We really pulled it up to that almost breaking point where you did start to see unpleasant grain.

Excerpt from “fxpodcast #294: Making the 360 degree short HELP,” Mike Seymour, Sydney University, Fxguide.com

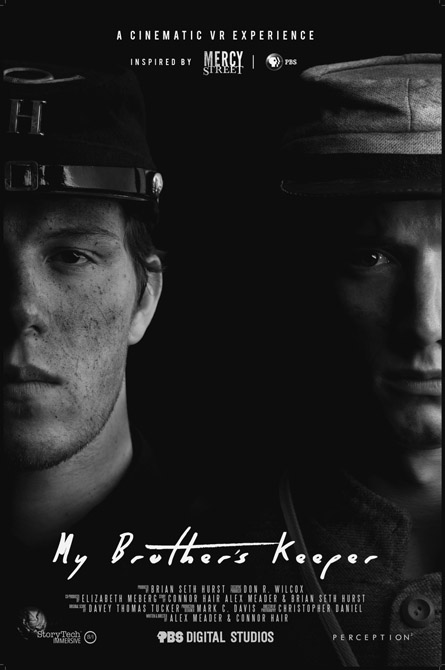

Achieving beautiful visuals can be a challenge given all of these limitations. Some cinematographers find ways around them by picking different VR cameras depending on the light conditions and the type of shot needed. For example, three different VR systems were used when shooting “Under the Canopy,” a documentary about the Amazon rainforest. The daytime shots were made using the Jaunt One; the night-time shots with a VR rig that was custom-made for the Sony A7S DSLR. Finally, the aerials were shot using a GoPro rig as the Jaunt One was too heavy for the drone. The key is to adopt a more “documentary” approach to VR cinematography, even for narrative projects. On the bright side, it can be fun and exciting to find ways of making the best out of the current VR cameras and to use the subtleties in the lighting to guide the participant’s gaze to the POIs.

When moving the VR camera, extra care must be taken to avoid exposing the viewer to motion sickness. Movement itself is not the issue; rather, it is caused by acceleration (change of speed), rotation of the sphere, and variations in the horizon line. Moving shots in VR are possible but challenging to do right. Motion-controlled dollies, cable-cams, or drones often provide the answer.

Eve Cohen, Director of Photography, “The Visitor VR”

If I had all the control in the world, the sets would be built and I would be able to build my lighting into the set. It’s a lot of production design, and it’s a lot of very strategically placed props in the frame to hide your lights. The other end of the spectrum is that you’re outside and you don’t have any control over the lighting. You are left with choosing the right time of day and knowing where to place the camera so that the flares aren’t too extreme. But there are also ways of lighting that need to be cleaned up later if you have a budget that can allow for that.

I tend to use lights that have a much smaller footprint, or lights that I can hide really easily. Whether that be light strips, like LED light strips that are getting wrapped around on the back side of a very thin lamppost to bring up the opposite side of where the light might need a little bit more ambience. I end up using a lot of LEDs, and a lot of practicals that are on dimmers. And a lot of production design to hide the cables.

The production design department needs to do more than it normally would. A lot of times in flat movies they don’t actually have to light things, whereas in VR a lot of times these practical lights have to actually light things.

I filmed a segment of “Memory Slave” at the Ace Hotel Theater, in downtown LA. There’s this whole lighting grid that’s set up because you’re inside of a theater space. So part of the production design and actually knowing that we were in a location where if you see all of our actual lights and units, it’s okay to see them because they’re on a lighting grid, and you know you’re in a theater, and that is part of the scene. I actually just repositioned almost every one of the lights that was on this grid to be doing something in the frame that I needed it to do.

Figure 7.11 “Memory Slave” ©Wevr, Seed&Spark

Halfway through the scene, there’s a lighting gag where everything turns off and just a spotlight comes up. And all of that was only possible because we staged this part of the scene in a theater space with somebody sitting up on the second level of the balcony. I don’t know that I would have been able to do that hiding of all of the lights. I probably would have had to paint them out.

Figure 7.12 Jaunt One camera mounted on a cablecam system to shoot “Under the Canopy” – credit photo Celine Tricart

Dailies

In VR, just as in traditional film/TV, reviewing dailies is a great way of making sure the needed shots were captured, and to learn from the day’s work. VR scenes can look and feel very different when watched stitched in a headset versus on a flat screen or a mobile 360° player. Most VR cameras come with dedicated stitching software that can render a low-resolution rough stitch quickly at the end of the day. This process can also potentially highlight technical issues and allow for a reshoot the next day, if needed.

Post-Production

It’s a wrap! Time has come to start post-production, which is where the real challenges of VR lie. The successive steps of a traditional VR post-production workflow are described below. Technical details and software are listed in Chapter 2.

Alex Vegh, Second Unit Director and Visual Effects Supervisor

To move the camera in “Help,” we started off with a cart system. We found that we were better moving the camera from above. We had a great deal of elevation changes. At one point we talked about doing motion control [moco], but we really found that there wasn’t a moco unit out there that would give us the freedom of movement and the length of movement that we wanted. So we wound up using multiple cable-cam systems.

It was all intended to try and capture everything in one take. There are three different sections – China Town, subway, and the LA River. The three sections were then tied together and seamlessly blended.

One of the big things was allowing the director to have the creativity to do what he wanted to do, and not have technology get in the way of that. One of the things we did learn along the way was that the cable-cam systems are very capable – they’re generally pre-programmed and you can slow it up or speed it down, but it’s always going to go along the pre-programmed path. Normally the actors would act and you have the camera following them. But our camera is going to move where it’s going to move – there’s no adjusting for that. So it’s a different sensibility.

Figure 7.13 From: Behind The Scenes: Google ATAP “Help”

Excerpt from “fxpodcast #294: Making the 360 degree short HELP,” Mike Seymour, Sydney University, Fxguide.com

Pre-Stitch

Pre-stitch is a purely technical step consisting of rendering a rough stitched version of the foot-age in preparation for editing. It is similar to making a rough previz of the future CG shots to help the editor cut the scenes together. Most stitching software can render low-resolution/low-quality stitched footage, which will allow the editor to go through the footage and select the best takes.

Editing

During the editing process, the director and the editor work together to pick the best takes and piece the film together. The pace of a VR film can feel very different when watched in a headset compared to when it is watched in 360° on a flat screen. It is recommended to check the edit in a headset on a regular basis. It is also during editing that the “POI-matching” technique can be applied and the transitions from shot to shot be tested, as described in Chapter 6.

Final Stitch

Once the editing is locked, the final stitch process can start. This is the only post-production step that is unique to VR and can be time-consuming and expensive. It is vital to have tested the entire workflow and, more specifically, the various stitching solutions before entering production. Depending on whether the film is in 2D or stereoscopic 3D, the chosen VR camera, and the complexity of the shots, the stitch can become extremely complicated. The creative team reviews the stitched shots once they are ready, but it is advisable to involve the VR supervisor/DP in this process, as some stitching imperfections can be hard to detect. Someone who has experience in VR will be able to spot these and make sure the final stitch is as perfect as it can be.

Some plug-ins specifically for VR, such as Mettle’s Skybox or Dashwood, provide tools to de-noise, sharpen, glow, blur, or rotate the sphere in a way that is compatible with Adobe or Final Cut Pro.

Figure 7.14 Stitching imperfection

VFX

In certain cases, the stitching of specific shots can be too difficult for traditional stitching software. It is then necessary to use advanced VFX tools to do this, such as The Foundry’s Nuke and its “CARA VR” toolkit.

Other types of VFX often used in VR include stabilization (to prevent motion sickness), tripod/drone/cable-cam replacement, and plates to hide lights or crew, etc. More traditional VFX, such as those used in film/TV, come second. A stunning example of VR VFX work is Google Spotlight Stories’ “Help,” directed by Justin Lin.

Color

Color is a post-production step carried out under the supervision of the director, the director of photography, and the colorist, yet the VR supervisor/DP can be valuable at this phase to share his/her knowledge of VR and, more specifically, the HMDs. The current HMDs have a much lower quality than calibrated digital cinema screens in terms of resolution, dynamic range, and color reproduction. Most VR headsets have OLED displays, which have known issues when it comes to true black and smearing. It is vital to adjust the color grading and the black level when exporting for HMDs.

Gawain Liddiard, Creative Director, “Help,” The Mill

Something we found throughout the project was almost every tool broke. It was quite bizarre that everything we came across just didn’t work as expected, and the blur is one of the examples I always go to. Something as simple as a 2D blur doesn’t work in an equirectangular environment where you want to blur the horizon less than you blur the top and bottom. Part of it was just being diligent, our 2D team had to be incredibly careful, and simple tasks such as roto[scoping] just took longer. And then the other side to it was there wasn’t sort of an overarching, fix everything, R&D tool that was created. It’s much like plugging all those little gaps of writing, lots of little small tools that allow us to tie it together.

Excerpt from “fxpodcast #294: Making the 360 degree short HELP,” Mike Seymour, Sydney University, Fxguide.com

Eve Cohen, Director of Photography, “The Visitor VR”

I spent a while researching standards in television, but nobody has come up with this standardization for VR color grading. When you do export a VR file, it would go onto Gear, it would go onto Oculus, it would go onto the Rift, or HTC, and I kept asking, “Well, don’t they all look different? They’re all going to look different. How do we grade for this output? How do we grade and export for this output?” And in normal filmmaking that’s pretty standard that you do a different digital path than you would for a theatrical. But we don’t have that yet in VR, but that needs to happen. If you’re doing a car commercial and you have a client who is really particular about the color of that car, it is going to be different on each headset. And there’s no way to control that right now.

Gawain Liddiard, Creative Director, “Help,” The Mill

There was a huge amount of back and forth when coloring “Help.” It was great that we did all the color here in-house. Greg Reese did all our color for us. He would work with grading a certain area that he knew he wanted to grab hold of separately, and then we’d work back and forth between Nuke and him. And then there was also ways that we found to solve the edge-of-frame issue. We would essentially overscan the edge, the entire frame, take a small sliver of left-handed frame and stick it on the right side, and a small sliver of the right-handed frame and stick it on the left side, so you had this safe zone buffer.

Excerpt from “fxpodcast #294: Making the 360 degree short HELP,” Mike Seymour, Sydney University, Fxguide.com

Figure 7.15 Color grading session for “A 360 VR Tour of the Shinola Factory with Luke Wilson” – ©ReelFX

One possible workflow for VR color grading is as follows. The first linear “match” grading is done before or during the final stitch to make sure all the cameras are even. Next is the linear primary and secondary grading within the spherical frame composites. Finally, the spherical frame is sent to “traditional” non-linear grading (in DaVinci, for example). Beware when grading an equirectangular unwrapped frame as any grades that get close to the edges will create a visible line when the sphere is mapped.

Sound

Sound post-production happens in parallel to the final stitching/VFX/color steps. It usually starts right after the edit becomes locked (although some preliminary sound design and music work can be done beforehand). When it comes to sound editing, there are no differences between VR and a more traditional post-production. Sound recordings are selected and assembled in a timeline. Things become more complicated when it comes to sound mixing. The positioning of the various sound elements in the VR sphere is a delicate, yet important, process. Dialogue, sound effects, soundtrack, and voice-over can be used as “cues” to influence the participants and set the POI. Just like in real life, sounds often precede visuals and allow us to create a mental representation of our surroundings, beyond the limits of our field of vision. Using the binaural or ambisonic technologies as described in Chapter 2, we are able to create and emulate a realistic and precise sound sphere to accompany VR films. Unfortunately, sound often comes as an afterthought even though it is key to creating presence and immersion in the VR story world.

Anthony Batt, Co-Founder and Executive Vice President, Wevr

The early attempts that we were making were very visually focused. What we’ve learned through doing that is that humans are into relations and in our real lives, audio plays a much richer input device than we’ve realized. That’s a great creator of a simulation, whether it feels like a film or it feels like a video game, or it feels like anything. Not paying attention to the richness of how audio needs to be placed and played back is a big miss.

We have learned and recognized and respect that. But it’s different than having Hans Zimmer’s score or something for us. It’s more about creating the right room tone and have the right spatial audio. A lot of people that jump into making VR really focus on the visuals first. They don’t realize how important sound is.

Titles

Titles, subtitles, and supertitles (supers) in VR can be hard to place in space (and in depth, as is the case for stereoscopic 3D projects). If the POI and the cor-responding title/subtitle are placed too far from each other, the participants might not see it at all. Ideally, all the added elements should be reviewed and adjusted in an HMD. Sometimes a title is placed in multiple positions in the sphere to ensure it does not get missed, such as in the example in Figure 7.16.

Another possibility is to use a game engine to “host” the VR film and use its tracking capacities to make titles and supers appear in the participants’ field of vision, no matter where they are looking.

Just like the previous post-production steps, quality control of the title placements should be done by someone who is knowledgeable about VR, and who can only make the final project better.

Distribution

The audience for virtual reality is currently limited to early adopters due to the price and technological limitations of HMDs. However, the fast and steady growth of 360° platforms such as YouTube 360 and Facebook 360 considerably opens the market for VR creators who are willing to have their content seen on a flat screen instead of a headset. Most of the current high-end VR content is financed by the various distribution platforms themselves. This brings the VR industry closer to the TV industry than to the cinema system of distribution. Content is paid for upfront and then belongs to the platform, instead of being created in the hopes of finding distribution and monetization after the fact. This approach might change in the months or years following the publication of this book, but is the case as of 2017.

Figure 7.16 “A 360 VR Tour of the Shinola Factory with Luke Wilson” directed by Andrew & Luke Wilson – ©ReelFX

Steve Schklair, Founder, 3ality Technica and 3mersiv

This is where we get deeply into the realm of opinion. I am still skeptical in the viability of monetizing narrative scripted VR content. In today’s world, a majority of professional VR content is coming out of corporate marketing budgets. You could possibly monetize educational material. You could possibly monetize industrial and corporate projects. You can monetize product demos as they come in on a work-for-hire basis. The traditional short film narrative scripted that you view for entertainment purposes, I don’t know how you monetize that, but since so much is being done in that area maybe I’m just missing something. I’ve been involved with a few projects of this nature, but it has been difficult to monetize those. Maybe someone in the future will figure it out or when the audience hits critical mass it becomes obvious. The idea behind a lot of companies is that there’s going to be a “Netflix” of VR, an entertainment channel. I’m having trouble buying into that because what happens to your business model when Netflix wants to be the Netflix of VR? Or maybe it’s YouTube being the Netflix of VR, if you want to use that as a way to describe it. I’m not sure what the potential is for monetizing or not. You’d need a very large audience in order to monetize content in that way. I’m not sure they’re going to get that size of an audience for this type of content.

Festivals

A lot of prestigious festivals now have a VR selection, which has encouraged storytellers to create bold VR experiences that push the boundaries of the medium. One of the most renowned is the Sundance Film Festival and its “New Frontier” program. New Frontier has been accepting VR submissions for many years, but the overwhelming quantity of virtual reality submissions has led to the creation of VR-specific venues that are now ticketed. With Sundance leading the way, additional festivals are adding VR.

Sundance

The Sundance Film Festival committee encourages the submission of inventive, independently produced works of fiction, documentary, and interactive virtual reality projects. Projects must be viewable via Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, Samsung Gear VR, or Google Cardboard. The late submission date is usually in August.

Figure 7.17 Sundance festival-goers immerse themselves in new-media artist Oscar Raby’s virtual-reality piece “Assent.” Photo by Neil Kendricks

SXSW

South by Southwest is an annual film, interactive media, and music event that takes place in mid-March in Austin, Texas. The last date to apply is usually in October.

Tribeca Film Festival

Tribeca exhibits experiential work throughout the festival to showcase new forms and uses of media, including virtual and augmented reality. The last date for submission to this category is usually in December.

Atlanta Film Festival

Atlanta Film Festival is now open for groundbreaking works in virtual reality. The late deadline for submission is October.

Cinequest Film & VR Festival

This vanguard film festival is organized in San Jose, Silicon Valley. Cinequest fuses the world of the filmed arts with that of Silicon Valley’s innovation to empower youth, artists, and innovators to create and connect.

Dubai International Film Festival

“DIFF” is a leading film festival in the Arab world. Since its inception in 2004, the festival has served as an influential platform for Arab filmmakers and talent at an international level.

Kaleidoscope VR

Kaleidoscope is not only a film festival but a community for virtual reality creators to share their work, build a fan base, secure funding, and discover new collaborators. There is no deadline for submissions; Kaleidoscope accepts projects on a rolling basis.

World VR Forum

The World VR Forum is a Swiss non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the virtual, augmented, and mixed reality industries.

Many more VR festivals and events can be found online and with the help of VR-focused social media groups. Festivals are a great way of getting innovative and artistic VR creations seen by wide and diverse audiences.

Shari Frilot, Founder/Chief Curator of New Frontier at Sundance Film Festival

The things I look for as a film programmer are a bit different than what I look for in VR. With film, it’s rarely different because it’s a very mature medium and it’s a mature industry. With VR, every year it’s different. Last year, in 2016, I looked for innovation and got excited about demos that showed a new kind of technology. For example, I got really excited about volumetric capture. There wasn’t a lot of story there but I knew what they had achieved was significant. Sometimes, we bring technologies that are not necessarily driven by story, but to expose our storytelling audience to these technologies so that maybe they could do something with it. Maybe it could expand their storytelling culture.

Now, last year, I knew going in judging that I did not want to show any demos. I really wanted to show work that was breaking ground in storytelling. There are so many films about Africa that it was really hard for a film about Africa to make it to the selection. There was one, but it wasn’t going to be ready on time for the festival. The VR experiences had to be the best of what was out there that I had seen of its kind. I drew a lot from my own experience looking at work and listening to my response and trusting it. Trying to learn how to trust it. My instinct is to do both this coming year. There are new trends that are coming up that I know are going to be important.

I think I’ll continue to separate VR as an independent platform and work to really serve the community that is now coming to the festival that, basically, doesn’t even see films. I’m trying to figure out how to get them to see films as well as VR!

Choosing the Right Platform/Monetization

Most of the current distribution platforms are listed in Chapter 2 (for live-action VR) and Chapter 3 (for game engine-based VR), but many more are likely to have been released since the publication of this book. Once the festival round is completed (if any), it is time to pick the right “home” for your VR project.

Unfortunately, as noted above, most of the high-end VR content is produced and financed by the distribution platforms, such as Oculus or Within and its “Here Be Dragons” production department. Even if none of the established platforms is financing your project, you should have discussions with them as early as possible and try to put a distribution deal in place. If no distribution has been agreed on, you will likely have to publish and publicize your project yourself, either through the non-curated platforms such as YouTube 360 (for non-game engine content) or by packaging it into a downloadable app.

As of the first quarter of 2017, only 30 VR apps have made over $250,000 on Steam, according to Valve. More than 1,000 titles are supported on the technology. Only a few VR titles have seen more than $1 million in revenue. However, Steam is a high-end gaming platform compatible only with expensive headsets such as the HTC Vive.

When it comes to narrative live-action content, it is complicated to assemble precise numbers. Currently, most VR content is accessible for free to encourage audience growth. Even high-end and expensive content such as that from Felix & Paul is free. Once the market reaches its maturity and enough HMDs are sold, it is likely that these platforms will switch to a subscription-based or pay-per-view system. The Transport platform by Wevr has already made this transition: since 2017, users can have access to a number of free curated VR experiences, but can also pay a yearly fee to get access to premium, high-end content. The mobile version is offered at $8/year, and the PC+mobile version at $20/year. Time will tell if this system works and if the market is ready for the switch to a subscription model.

Ryan Horrigan, Chief Content Officer, Felix & Paul

While some of the platforms/hardware makers are funding projects (Oculus, Google, HTC, PlayStation), they are doing so in exchange for often lengthy exclusivity periods and with the intent to make the content free for all of their users, avoiding monetization for the time being as they seek to grow. This has been a great way to kick-start the industry for content studios like ours; however, as user adoption continues to spike in the next one to two years, we’ll start to see content financing from other avenues become more readily available. Such as via China, from SVODs [subscription video on demand] like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu, telecoms with marketing and SVOD dollars like AT&T and Verizon, as well as from the world of independent film and television finance.

While some content studios are also distribution platforms that sit on top of Oculus, PlayStation, Daydream, and HTC Vive, we have deliberately remained platform agnostic so that we can be nimble and flexible on a project-to-project basis in terms of how we finance and distribute said projects, working more closely with the hardware makers/core VR platforms.

We see a near-term opportunity for models to develop akin to those from independent film and television finance, whereby financing and distribution can be arranged across platforms via pre-sales of various windows and territories. It’s important for content studios to seek monetization (direct-to-consumer TVOD [transactional video on demand] in particular), in order to become self-sustaining entities that can ultimately fund their own productions for wide distribution across platforms, taking the onus off VR hardware makers/platforms such as Oculus and Google, who are surely not interested in funding VR content indefinitely once a self-sustaining market is established. After running many detailed financial models in regards to content financing and distribution, also taking into consideration the current number of active VR users across platforms, and projections for user growth in one year, two years, and beyond, we believe making premium VR series (scripted and non-fiction) will be a profitable business within one to two years, once said content is distributed across platforms in TVOD and SVOD windows.

Ryan Horrigan, Chief Content Officer, Felix & Paul

Monetization is coming, but as an industry we must do more to differentiate for the consumer what is branded/marketing-driven content for free, versus high-quality original content worth paying for. The move to episodic content will help delineate between the two, however. Platforms must not wait too long to begin training audiences that premium quality is worth paying for. It’s easy to neglect this in the short term as we all seek user growth, but in the long term it’s the key to a self-sustaining business model.

Direct-to-consumer pay-per-view (TVOD) is much more interesting to me than SVOD, as there is more upside perhaps for content creators, which will only help them self-fund their own content. SVOD incumbents such as Amazon, Netflix, and Hulu will play a big part in funding and licensing content, the three of which will also lead the way in terms of VR SVOD business. They already have millions upon millions of people paying $12/month or $99/year for their TV and film content, so as soon as there are enough VR users, we expect them to make and distribute plenty of original VR content. The barrier to entry is quite low for them as they don’t have to acquire new users like others that may attempt SVOD models as VR-only distribution platforms. In other words, these incumbents have an advantage and a pre-existing user base to pivot into VR with.