Ofoto began life as an online photography service based in Berkeley, California. The service provided three basic features:

It let people upload JPEG images so that others could view them by simply visiting the website.

It let people create photo albums and share them online with friends.

It enabled users to purchase prints online. This feature was supposed to be the foundation for Ofoto’s business model, which was based on the premise that people would want traditional, printed photographs.

Ofoto later added a 35mm online film processing service and an online frame store, as well as some other services, but its core pattern still embraced a core model of static publishing. In May 2001, Eastman Kodak purchased Ofoto, and the Ofoto Web Service was rebranded in 2005 as the Kodak EasyShare Gallery.

Flickr is another photo-sharing platform, but it was built with the online community in mind, rather than the idea of selling prints. Flickr made it simple for people to tag or comment on each other’s images, and for developers to incorporate Flickr into their own applications. Flickr is properly a community platform and is justifiably seen as one of the exemplars of the Web 2.0 movement. The site’s design and even the dropped e in the company name are now firmly established in Web 2.0’s vernacular.

This comparison involves the following patterns:

Software as a Service (SaaS)

Participation-Collaboration

Mashup

Rich User Experience

The Synchronized Web

Collaborative Tagging

Declarative Living and Tag Gardening

Persistent Rights Management

You can find more information on these patterns in Chapter 7.

Flickr is often used as an information source for other Web 2.0 platforms or mechanisms. It offers simple application programming interfaces (APIs) for accessing its content, enabling third parties to present images in new contexts and to access and use Flickr’s services in their own mashups or other applications. Bloggers commonly use it as an online photo repository that they can easily connect to their own sites, but the APIs offer much more opportunity than that. Programmers can create applications that can perform almost any function available on the Flickr website. The list of possible operations is vast and covers most of the normal graphical user interface’s capabilities.

Note

Flickr also lets developers choose which tools they want to use to access its services. It supports a REST-like interface, the XML Remote Procedure Call (XML-RPC), and SOAP (and responses in all three of those), plus JSON and PHP. For more, see http://www.flickr.com/services/api/.

Developers can easily repurpose Flickr’s core content in mashups, thanks to its open architecture and collaborative nature. A mashup combines information or computing resources from multiple services into a single new application. Often, in the resulting view two or more applications appear to be working together. A classic example of a mashup would be to overlay Google Maps with Craigslist housing/rental listings or listings of items for sale in the displayed region.

Flickr’s API and support for mashups are part of a larger goal: encouraging collaboration on the site, drawing in more users who can then make each others’ content more valuable. Flickr’s value lies partly in its large catalog of photos, but also in the metadata users provide to help themselves navigate that huge collection.

When owners originally upload their digital assets to Flickr, they can use keyword tags to categorize their work. In theory, they do this to make it easier to search for and locate digital photos. However, having users tag their photos themselves only starts to solve search problems. A single view of keywords won’t work reliably, because people think independently and are likely to assign different keywords to the same images. Allowing other people to provide their own tags builds a much richer and more useful indexing system, often called a folksonomy.

A folksonomy (as opposed to a top-down taxonomy) is built over time via contributions by multiple humans or agents interacting with a resource. Those humans or agents apply tags—natural-language words or phrases—that they feel accurately label what the resource represents. The tags are then available for others to view, sharing clues about the resource. The theory behind folksonomies is that because they include a large number of perspectives, the resulting set of tags will align with most people’s views of the resources in question.[37] The tags may even be in disparate languages, making them globally useful.

Consider an example. Say you upload a photo of an automobile and tag it as such. Even though a human would understand that someone looking for “automobile” might find photos tagged with “car” to be relevant, if the system used only a simple form of text matching someone searching for “vehicle,” “car,” or “transportation” might not find your image. This is because a comparison of the string of characters in “automobile” and a search string such as “car” won’t produce a positive match. By letting others add their own tags to resources, Flickr increases the number of tags for each photo and thereby increases the likelihood that searchers will find what they’re looking for. In addition to tagging your “automobile” photo with related words such as “vehicle,” “car,” or “transportation,” viewers might also use tags that are tangentially relevant (perhaps you thought the automobile was the core subject of the photo, but someone else might notice the nice “sunset” in the background and use that tag).

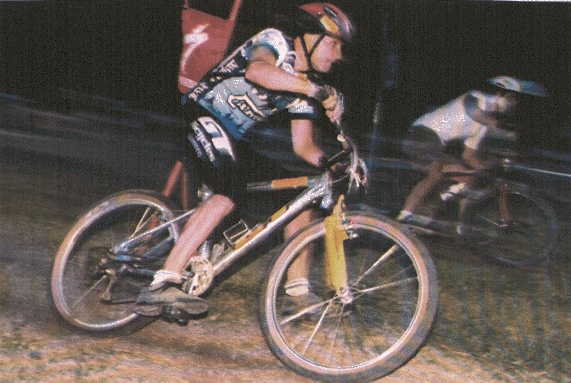

With this in mind, how would you tag the photo in Figure 3-4?

We might tag the photo in Figure 3-4 with the following keywords: “mountain,” “bike,” “Duane,” “Nickull,” “1996,” “dual,” and “slalom.” With Flickr, others can tag the photo with additional meaningful keywords, such as “cycling,” “competition,” “race,” “bicycle,” and “off-road,” making subsequent searches more fruitful. Semantic tagging may require more thought, but as a general rule, the more minds there are adding more tags, the better the folksonomy will turn out.

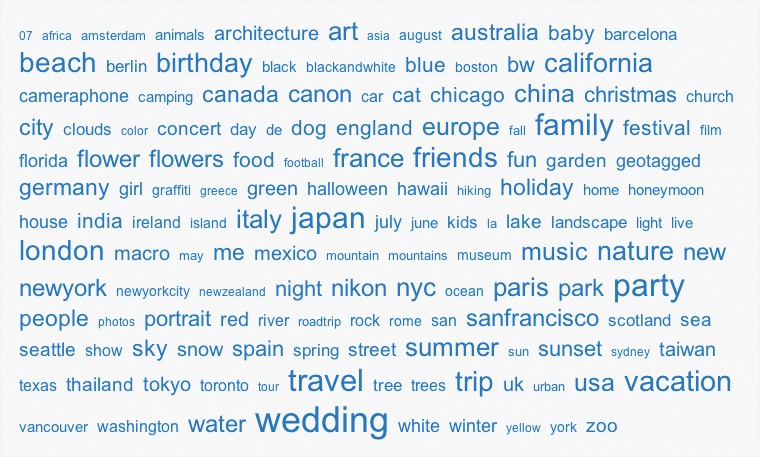

Flickr has also built an interface that lets people visiting the site see the most popular tags. This is implemented as a tag cloud, an example of which appears in Figure 3-5.

The tag cloud illustrates the value of a bidirectional visibility relationship between resources and tags. If you’re viewing a resource, you can find the tags with which the resource has been tagged. The more times a tag has been applied to a resource, the larger it appears in the tag cloud. You can also click on a tag to see what other assets are tagged with the same term.

Another advancement Flickr offers is the ability to categorize photos into sets, or groups of photos that fall under the same metadata categories or headings. Flickr’s sets represent a form of categorical metadata rather than a physical hierarchy. Sets can contain an infinite number of photos and may exist in the absence of any photos. Photos can exist independently of any sets; they don’t have to be members of a set yet can be members of any number of sets. These sets demonstrate capabilities far beyond those of traditional photo albums, given that each digital photo can belong to multiple sets, one set, or no sets. In the physical world, this can’t happen without making multiple copies of the photos.

[37] Flickr’s tagging is effective, but it represents only one style of folksonomy: a narrow folksonomy. For more information on different styles of folksonomy, see http://www.personalinfocloud.com/2005/02/explaining_and_.html.