CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4

There’s No Stopping It Now

From Bans to Bookies

[T]he sweetness of winning much

and seeing others lose had turned to the

sourness of losing much and seeing others win.

—George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

Traditional American entertainment and relaxation with dice and card playing goes far back to the original colonies, over a hundred and fifty years before the American Revolution. But the explosion of gambling was inevitable under the new democracy. And with the purchase of Louisiana at the turn of the nineteenth century came New Orleans, where cards were dealt, dice were rolled, and craps (the American version of hazard) was played day and night. For the next hundred and fifty years that city would remain a sanctuary from the country’s gambling prohibition.

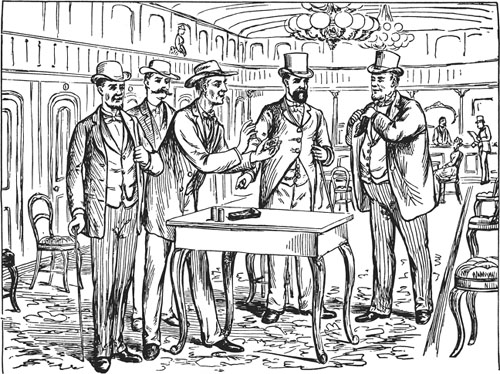

Just as in most of Europe, America had laws against gambling; yet in the bigger cities, in the more fashionable districts, gambling houses were plentiful. Gambling floated up the Mississippi to Vicksburg, then on to Memphis, branching up the Ohio to Louisville, Cincinnati, and Cleveland. By the 1830s paddle-wheel riverboats were sailing upstream along the Mississippi, attracting an eclectic group, from wealthy southern plantation owners with more money than sense to snake oil salesmen and cowboys.

FIGURE 4.1. Riverboat gambler sharking a wealthy businessman in three-card monte. From George H. Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi (Cincinnati: Devol and Haines, 1887), 193.

The typical gambler knew almost nothing of the mathematics of risk but did have a sense of the rarity of hands—that drawing a full house is almost a hundred times more likely than drawing a straight flush and that a straight is almost twice as likely as a flush. Such information was part of the culture, though it wouldn’t have taken much mathematics to figure it out (see chapter 10, in particular table 10.1). Riverboat gamblers wagered on the wildest contests from craps to fly loo, betting that a fly in the room will land on one sugar cube or another at the end of a long table. Rich southerners were seen slapping papers on the table and crying out in southern drawl, “The deed to my plantation!” One of the richest plantation owners of the ![]() Louisiana lost everything, including his plantation, and became a croupier at a New Orleans gambling house.1

Louisiana lost everything, including his plantation, and became a croupier at a New Orleans gambling house.1

In 1848, when the first gold searchers started arriving, the city of San Francisco saw a rise in gambling. But when the next waves came late in the year to that city of only 25,000 at alarming rates (over 40,000 by the end of the year) from South America, Australia, and the East Coast cities of the United States, gambling became a serious concern. Saloons turned into gambling dens crowded day and night with immigrants mad for excitement and testing their luck on what fifty cents could do with the turning of a card. These new immigrants had some pocket money. They sold their land and possessions to move west in search of fortune. No doubt, where there is someone with money, there is someone ready to take it away. And so new gambling houses and brothels, posing as dance halls, opened all over the city, ready to entertain with wine, attractive women, and illusions of fortunes. In San Francisco one could play faro, chuck-a-luck, brag, high/low, or grand hazard in almost any of the over one thousand dodgy dance halls at all hours, day or night. New Orleans was no longer the gambling capital of the country.

During the Civil War, cities and towns rescinded gambling prohibition; gambling spread to all corners of the continent bringing new games such as monte and euchre. Card manufacturers designed patriotic face cards for each side, the Union and the Confederacy, and made a fortune. Each side saw this as a way for troops to learn more about the enemy and it would become a military tool to be used again in World War II (with the silhouettes of German and Japanese fighters), the Korean War, and the Iraq War.2 During the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, U.S. troops were given playing cards with fifty-two of the most-wanted enemies, ranked by importance—Saddam was the ace of spades, Qusay was the ace of clubs, and Uday the ace of hearts.

In downtown New York, at the end of the nineteenth century, there was hardly a street without a private gambling house well-known to the police, who would profit from kickbacks as well as a few turns of faro. Gambling in New York was the common pastime of the poorest workmen, discharged servicemen, and precocious street boys.

The center of gambling attraction in New York was at Pat Hern’s place, on Broadway, near the corner of Houston Street, where visitors would be generously treated with wine and supper. Or Morrissey’s in Union Square, splendidly furnished, welcoming, and, here, too, lavishly generous in food and wine at all hours of the day and night.

FIGURE 4.2. New York City poolroom in 1892. From Harper’s Weekly, April 2, 1892, University of Las Vegas Special Collections; image © 2000 HarpWeek, LLC. See also David Schwartz, Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling (New York: Gotham, 2006), 335.

Such perks were destined to become a feature of American gambling establishments, as it was for a time with the thermal bath spas in Europe. There would be free wines, cheeses, cakes, chocolates, biscuits, and nuts. Even those who were broke and hungry could get a meal at a gambling house.

Morrissey’s visitors were the fashionably dressed, wild, and wealthy high rollers who frequented the plush rooms night and day to drop tens of thousands of dollars at a turn ($1,000 in 1900 would be worth more than $26,000 today). Enterprising Americans had figured out a new way to lure and detain anyone with pockets of coins.

There were also sleazy houses. At 102 The Bowery, there was a downscale gambling house, where those who lost everything at Morrissey’s could win a few bucks and return to lose again at Morrissey’s. If you passed at night, a street hawker would size you up and, depending on what he saw, yell either “Hallo, old sport come and try your luck—you look lucky this evening; and if you make a good run you may sport a gold watch and chain, and a velvet vest, like myself” or “You look down at the mouth tonight! Come along and have a turn—and never mind your supper tonight.”3

As far back as the Revolutionary War, Americans had enthusiastically embraced gambling and had included almost every European game in their repertoire from poker to lottery.4 (The original idea of the lottery goes back to the Han Dynasty of China when funds were raised by a lottery system to finance the Great Wall.) Almost from the time the idea first came to colonial America, the lottery inspiration exploded into an immoderation of private lotteries and raffles administered not by the government to augment tax revenues for building roads or waging wars, as had been the traditional sponsors, but by private citizens and private organizations to build their bank accounts. There is a small difference between raffles and lotteries. In a raffle, each participant buys a ticket for a random drawing of a fixed prize, whereas a lottery prize grows with the number of ticket purchasers. Raffles go back to first-century Rome when members of the Forum would throw prize parties, banquets, and Saturnalias for political supporters where guests received door prizes. However, later, Florentine and Genoan merchants inflated the idea by encouraging the sale of products and used it to generate private profits.

Still later, Venetian princes saw it as a means to generate considerable municipal revenue. Some say that the first recorded lottery took place in 1444 when the Flemish city of L’Écluse raised funds for repairing the surrounding city walls.5 However, that was more of a raffle than a true lottery, for the prize was fixed beforehand at 300 florins (about $300,000 in today’s money). That was a time when an unskilled laborer earned about a penny a day on top of room and board, a time when a whole chicken or a night at a nice clean inn cost about one English penny. In today’s state lotteries it is often the case that nobody wins and so the pot grows and becomes more attractive for the next round and the next pool of participants. Though we must recognize that some form of lottery came to the Italian colonies by way of Flanders, the first true form of lottery happened in fifteenth-century Venice. By the mid-sixteenth century, Venice was teeming with lotteries—the Rialto district was filled with lottery hawkers selling tickets for cash prizes of 1,500 ducats (about $170,000 in today’s money).6 This new form of gambling flourished in the eighteenth century to finance wars, museums, and even universities.7 (Lotteries were used to finance the American Revolutionary War, the rebuilding of Faneuil Hall in Boston, the establishment of the British Museum, and the building of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia.)

The lottery came to America by inheritance and came to be part of the everyday life of the colonies; it played well in the parent country and when colonists were faced with dire economic problems, they naturally turned to what had worked before.8 These were still private lotteries, administered by companies claiming social benefits. In the thirty years before the Revolutionary War, 161 lotteries were approved by twelve colonies to build revenue for diverse purposes from building a lighthouse in New London, Connecticut, to paying for wars to founding Columbia University (at that time King’s College).9 In England at that time, alongside a rush of fraudulent lotteries that ignited disfavor among respectable folk, legitimate lotteries funded municipal projects, such as bridges and an aqueduct to serve London. After the American War of Independence, when so many in America gambled, the lottery was thought to be an honest business. Even prominent and upright statesmen such as Benjamin Franklin ran lotteries.10 George Washington bought tickets for the Virginia lottery of 1790, which was organized to help pave the streets of Alexandria. And in March 1826, Thomas Jefferson, then eighty-three and facing poverty in the last months of his life, received authorization from the Virginia legislature to dispose of his assets, including Monticello, as bonus prizes by lottery.11 However, by the 1820s, a growing trend of lottery gambling was becoming noticeable; it began to be viewed as a threat to legitimate business and industry, and there was a growing fear that America’s national industry would be gambling.12 Fraudulent lotteries were appearing everywhere. With the potential for enormous profits, lotteries became the cheating tool of any scammer with access to a press to print raffle tickets and means to advertise his own sweepstake. Agents disappeared after the drawings, so prizewinners seldom received their due winnings. Even the contractor for the Grand National Lottery (see figure 4.3) disappeared with several hundred thousand dollars and the grand prize winner—who should have received $100,000 (roughly $1.8 million in today’s money)—had to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to sue the City of Washington for his prize money.

FIGURE 4.3. National lottery ticket, 1821, as it appears in John Samuel Ezell, Fortune’s Merry Wheel: The Lottery in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960). Reproduced courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

Largely due to rampant lottery fraud, lotteries were made illegal in almost every state in America by the time of the Civil War; but after, with so much financial turmoil resulting from the war itself, the Southern states rescinded laws banning lotteries. In the north, the prohibition remained in effect, though it was never enforced. From 1872 to the end of 1894, thousands of lottery vendors all over New York City were operating untroubled by the law, many working from unconcealed shops, others by peripatetic dealing. As of January 1, 1894, lotteries in the United States were illegal. President Cleveland signed a bill into law closing all forms of interstate commerce to lotteries, ending the American lotteries for the next seventy years.

After World War II, most states changed their gambling laws to permit charitable organizations to conduct bingo operations and, over time, other gaming businesses, such as raffles and pull-tabs (multilayered paper tickets containing symbols hidden behind perforated tabs). Then, in 1964, because of mounting opposition to tax increases, New Hampshire legalized a low-stakes biannual lottery. New York and New Jersey followed, and the first legal off-track betting system (OTB) opened in New York. Then New Jersey reversed its gambling laws to permit casino gambling in Atlantic City. Growing liberalization of gaming sentiment led to California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of permitting gambling on Indian reservations. In 1986, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation opened a high-stakes bingo hall in Connecticut, generating $13 million in gross sales and $2.6 million in profits in 1986 dollars, which would translate to $25 million and $5 million in 2009 dollars. Soon afterward, Foxwoods Resort Casino opened within walking distance of the Tribal Nation to become the largest casino complex in the world. As of this writing, it has slipped back to being only the third largest—the second largest is the neighboring Mohegan Sun and the largest, to be called the Venetian Resort, is currently under construction in Macau. It will become the Asian capital of gambling as well as the world’s largest casino. In 2009, at the time of this writing, New York State is thinking that it has the answer to its budget deficit by opening development rights to Aqueduct, the state-owned racetrack, to bidders who will pay $250 million and add 4,500 video slot machines.13 And so, the cycle of gambling continues.

Perhaps, as Edmund Burke put it in a speech to the House of Commons at the end of the eighteenth century, “Gaming is a principle inherent in human nature.”14 And perhaps gaming is natural for the survival of our civilization. The biggest gaming houses in the world are not the casinos of Atlantic City or Nevada but the stock exchanges in New York, London, Frankfurt, Tokyo, and Hong Kong, and 115 other stock exchanges around the world, which every working day shift billions of securities from one place to another in adrenaline-gushing ventures. These gambles that may be primed by mixtures of greed and profit support our civilized existence, without which goods and services for much of the growing population of the developed world (now approaching seven billion) would starve.

Sometime back in the twelfth century a group of Frenchmen came up with the idea of selling shares in the ownership of their textile mill in order to finance its ongoing operations. In 1553, some rich and daring London businessmen gambled by purchasing shares in the Mysterie and Compagnie of the Merchant Adventurers for the Discoverie of Regions, Dominions, Islands and Places Unknown. The company sent three ships under the command of Sir Hugh Willoughby to places unknown at a time when news from sea and faraway lands would take months, if ever, to return. Early news was very bad; two of the company ships along with their crews froze in Arctic ice and for a time it seemed that the shareholders had lost their bet. But the third ship made it all the way to Russia and the crew negotiated a lucrative trade treaty with Ivan the Terrible, opening trade between England and a very rich Russia. The original investors hit a jackpot.15 Other companies quickly saw share selling to independent investors as a business model for success.

And so the idea of buying and selling shares spread to other countries in Europe and was eventually picked up by governments that sought to finance their wars. But several centuries would pass before the first real commodities trading stock exchange opened in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1531. Hamburg picked up the idea in 1558, followed by Amsterdam in 1619, followed by London and Paris later in the century. In 1792 Alexander Hamilton (as secretary of the Treasury) advised that American government debt securities be traded on the corner of Wall and Broad streets in New York City, where neighborhood coffee shops were abuzz with traders of bonds and stock issues. Twenty-three years later, the trading moved indoors at 40 Wall Street and later became the New York Stock Exchange.

At first, the exchanges were simply bets on current and future values of commodities with guesses about what the world would bring to the marketplace in the way of metals, textiles, and agricultural products. In Amsterdam smart money was laid on the Dutch East India Company (the first company to issue stocks and bonds). But who could know for sure that it would be the Dutch rather than the Portuguese who would secure trading posts in the Spice Islands? The bets were on fleets returning with everything Eastern, from cloves to gems. However, there was always a better-than-even chance for a shipwreck.

Take the case of the Dutch tulip mania that moved through buying and trading in 1636 when prices went so high a single rare tulip bulb could fetch a house and land, as well as a carriage with a pair of horses.16 The next year the tulip market got jittery and the market wilted—imagine the pain of those who traded their houses for valueless bulbs. Or take that of the South Sea Company of London, whose shares in 1720 shot up tenfold in just eight months. Thousands of investors were bankrupted by betting on the company’s overvalued claims of profitability; in turn many investors, including the king and prime minister, put down very little of their own money to buy the shares on credit and the company was left worthless.

And what about insurance? Is that not a form of wagering with a hefty hedge? The idea was not born in the coffeehouses of London but did get a terrific boost from Lloyd’s, the coffeehouse at the corner of Abchurch Lane and Lombard Street owned by Edward Lloyd. There, a group of underwriters met to gamble on everything from ship risks, overdue voyages, fires, burglaries, earthquakes, and tramcar accidents to insurance against having twins or against the queen passing through certain streets on her Jubilee. Shipowners and merchants frequented Lloyd’s, and, since Lloyd himself was a newspaper publisher, his establishment naturally became the hub of shipping news and bets on commerce. (Until the end of the nineteenth century, almost all newspaper news was about shipping, listing ships’ arrivals and their contents.) The company grew to become the world’s leading insurance market. Even today, it is not a company but rather a market for insurance, just as it was when its underwriters met at the coffeehouse in the second half of the seventeenth century. A company called Phoenix that met at the Rainbow Coffee House at 15 Fleet Street underwrote the first fire insurance policies sixteen years after the Great Fire of London.17 Was that not gambling? Those early coffeehouses, though dim and scant, were perfect places for betting and insurance transactions to occur along with merchant affairs and all kinds of political gossip, and both social and business news.

In the 1920s shareholders borrowed to invest in a market, but their investment returns could not cover the interest rate on their borrowed money. When prices fell in 1929, millions of investors couldn’t pay their loans and the banks were left with too many defaults to pay depositors who demanded their money.

At the age of fourteen in 1891, Jesse Livermore had a job chalking stock quotes on a board for Paine Webber. By recording and analyzing stock patterns over the next six years, he was able to make some predictions and make $10,000 from $5 by trading at bucket shops, small-time betting shops that would accept small transactions, often within coffeehouses, drugstores, and hotels. Some were dishonest, posting false prices, but most were legitimate. Livermore made his first million just before a substantial crash in 1907 and, in the wake of the 1929 Wall Street crash, sat on a reputed fortune of $100 million.18 How did he do it? By mastering the art of selling short; in other words, by betting that the values of some stocks would drop, and even betting on the likelihood that some companies would go bankrupt.85 Very clever, but by the age of sixty-two he was bankrupt.19 A year later, on November 28, 1940, at 4:30, Jesse Livermore walked into the Sherry-Netherland Hotel on Fifth Avenue, sat at the end of the cloakroom, and shot himself in the head with a .32-caliber Colt automatic pistol.20

At the end of World War II, Alfred Winslow Jones, who was then a financial journalist for Fortune, took Livermore’s short-selling idea one step further in creating a fund that hedged investment risk, which has now come to be known as a hedge fund.21 As the name implies, he minimized his risk by hedging his bets, a phrase that came out of roulette where one places a bet on the hedge between two competing choices.22 Until then, most investments were bought long, that is, in the hope that their values would soon increase. The idea was as old as insurance; in England’s great lottery years of the early nineteenth century, Londoners could insure their lottery tickets by betting that their number would not be drawn on a particular day.23 But Jones hedged his bets by going long as well as short; that is, identifying shares that were overvalued and betting that their value would decrease.24 He borrowed such shares, immediately sold them, and later when their value plummeted bought them back at the lower price, exactly the sort of thing Livermore did to make his fortune. Any profit made would cover his long shares and so his risk in picking stocks more aggressively was minimized.

Thousands of speculators, including hedge funds, buy shares in companies that have no products other than the cash that comes from issuing their own stocks. They are the penny stocks whose prices can be manipulated by “pump and dump” schemes. These are companies with little fundamental value and no other business beyond the capability of printing shares by the millions. Promoters manipulate the stock by posting glowing information on bulletin boards or through brokers who contact investors through mass e-mails. Speculators, who do not own or borrow shares, engage in naked short selling; they place bets that stock prices will decline. Pumping and dumping works in the short run before everyone discovers that the company is worthless. Then the promoters bail out and the price hits a bankrupting bottom.

And now, in the twenty-first century, we can bet not only on plunging values of shares but on credit-default swaps, making it possible for us to bet that particular companies will default on repaying their loans. “Such bets on credit defaults,” said the billionaire George Soros, predicting the 2008 economic meltdown a year before it actually happened, “now make up a $45 trillion market that is entirely unregulated. It amounts to more than five times the total of the US government bond market. The large potential risks of such investments are not being acknowledged.”25

Shipwrecks on the high seas are now rare and the outcomes of many ventures are more certain, but for the novice, modern trading is as much a gamble as what happens on the green tables at Vegas.