INTRODUCTION

If you read no further than this page, we want you to know two things before you put the book down:

1. Millennials want to be happy and effective at work.

2. You can provide an environment where Millennials can be both happy and effective without ruining your organization, if you focus on what actually is important to them.

These two points are the essence of what we’ll be talking about. But the trick is knowing what to do. In this book, you’ll learn who Millennials are, what they want, and what to do about it.

“But it’s impossible to make Millennials happy,” you might say. “They are so unreasonable! They want the newest gadgets. They want to work three-hour days at full pay and to bring their pet, or their parents, or both to work every day. They don’t understand how business works! If you knew about the bizarre things I’ve seen them do or heard the stories I’ve heard, you wouldn’t say that it is possible to make them happy without changing the very nature of work!”

Well, sometimes appearances—and even behavior—can be misleading. We’ll explain how Millennials view the world of work, what they want, and how you can deal with them effectively, whether you are a coworker, a manager, an HR professional, or someone in charge of talent strategy for your organization.

Fundamentally, Millennials want to do interesting work with people they enjoy, for which they are well paid, and still have enough time to live their lives as well as work. Everything you need to do about Millennials follows from there.

Let’s Start with Who We Are Calling Millennials

Throughout the book we use “Millennials” to refer to a specific group of people, those born between 1980 and 2000. They have also been called Echo Boomers, Gen Y, and NetGen.

Millennials have grown up with greater access to technology than earlier generations. They are typically proficient with new technology (some say addicted to technology and uninterested in human contact), and many people believe their skill with new technology makes Millennials an asset to organizations.

Millennials have also been described as needy and entitled. Their detractors say that is because life was easy for them when they were growing up, at least in comparison with their parents. On the other hand, many of their families experienced financial hardship as a result of economic and social shifts. So some people posit that these hardships make Millennials skeptical of organizations in general and authority within organizations in particular. They have been derided as disloyal, uncommitted, and unwilling to work hard.

We have found these stereotypes of Millennials to be largely the same everywhere we have done our research. Though the details of the behaviors associated with these stereotypes might differ, the basics are consistent in all of the countries included in our research.

How We Got Here

This book introduces and explains the results of a series of projects we have worked on between 2008 and 2015. The data used for this book are global and include a total of more than 25,000 responses from Millennials and more than 29,000 responses from older employees from 22 countries. The research included both surveys and fieldwork conducted by us (Jennifer and Alec) and our colleagues directly with global organizations, and from the World Leadership Survey, which is an ongoing research effort funded by the Center for Creative Leadership. In addition to these data, we conducted numerous interviews and focus group meetings in most of the countries. The work of many of our colleagues helped produce the data used here, and we are grateful to them for their contributions.

We decided to write this book because we hear so many generalizations about Millennials promoted by pundits, consultants, and even some researchers—generalizations based mostly on anecdotes and not on real and rigorous data. Just as important, even when the conclusions reached by others are based on data, they typically focus on only one or two factors, not the complete package of who Millennials are and what they want.

When we took a step back to think about what we had learned from all of our different projects, we realized that we had developed an unexpectedly complex picture of Millennials globally. Considering all of the stereotypes we had read about in newspapers and online and had heard about from clients and colleagues alike, we kept finding ourselves saying “yes, but . . .” or “no, but . . .” The caricature-like descriptions we heard didn’t live up to the complex reality we encountered during interviews and focus groups and saw in our data. Since our job (our calling actually, but that’s a different conversation) is to provide information that people at all levels in organizations can use to make themselves and their workplaces more effective, we decided it was time for something different from the caricatures of Millennials. Those who work with and lead Millennials need an accurate picture of what the Millennials want from work, and how organizations can benefit from that knowledge: a picture that is both nuanced and simple enough to be actionable.

So that’s what we intend to do. But before we start, some background information.

Who We Studied

The survey data reported in this book come from just under 25,000 Millennial respondents from 22 countries: Brazil, Canada, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States. Those respondents work in more than 300 different organizations, most medium to large in size. All sectors of the economy are represented in the data set: government, non-profit, and for-profit. Industries include technology, food service, retail, aerospace, manufacturing, and professional services, among others. The majority of our survey data comes from organizations in the professional services industry, which is also where we conducted most of the interviews and focus groups. While our data are global, the majority of survey responses are from the United States.

Because we find it to be impossible to talk about Millennials without mentioning other generations, we periodically include data from more than 29,000 people from older generations in our databases (primarily Gen Xers and Baby Boomers). These older respondents come from the same organizations and industries as the Millennials we are studying.

While the standard definition of the Millennial generation encompasses everyone on the planet born in a 20-year range, we studied only those Millennials currently in the workforce, which means those born from 1980 to 1995. Most stereotypes about the Millennial generation at work primarily focus on a specific subset: people in professional, technical, managerial, and executive positions who have college degrees (bachelor’s or higher). Our sample reflects this, so it is made up of Millennials in these types of positions. Our sample doesn’t represent all Millennials everywhere.

In general, we find that Millennials around the globe have remarkably similar perceptions about the workplace. Differences show up in how strongly people respond to a certain topic, not the direction of the belief. And the differences are largely a function of individuals’ economic environments. For example, all Millennials keep an eye out for new opportunities, and well-educated Millennials in developing economies (e.g., Brazil, India, and China) often have more opportunities to change jobs than those in economies which are more mature (e.g., France). Where we see interesting country differences in the global data, we make note of it.

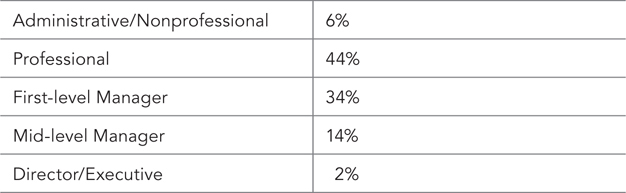

Organizational Level

All of the participants included in the results reported here were in support, professional, managerial, and executive roles (for more detailed information by country, see Appendix I.1).

TABLE I.1 Millennials and Organizational Level

Gender

The sample was well balanced with regard to gender, including slightly more men than women (51 percent men, 49 percent women; for more detailed information by country, see Appendix I.2). Though Millennial men’s and women’s responses to some of the questions did differ slightly in some countries, the differences weren’t large. We will tell you when the differences are meaningful.

Education

Most respondents in all countries and at all levels had university degrees (80 percent). In some cases, people were working at a job while simultaneously pursuing a university degree.

Married and Children

Although they are young, 25 percent were married, and 9 percent had children. Twenty percent of those who had children said they had primary childcare responsibilities (for more detailed information by country, see Appendix I.3).

As noted earlier, our sample is not representative of all Millennials everywhere. We are not claiming it is. It is, however, a very large sample of Millennials working in a range of organizations in professional or quasi-professional roles. This book speaks to the characteristics, behaviors, proclivities, and desires of that group.

Generalizations Are Not Always True—Including This One

Now that you know how we collected the data used for this book, it is important to explain that no matter how many people you survey and interview, and no matter how complex and apparently accurate your statistics are, there will always be some who don’t fit the general descriptions. In other words, no generalizations about people are always true, including the ones in this book.

Why? Because there are always outliers—people who don’t fit a generalization. For example, in general men are taller than women. But every man isn’t taller than every woman. In fact, some women are taller than most men. So while the generalization that men are typically taller than women is true, it isn’t true for every man and every woman.

Even though there are outliers, that doesn’t mean the generalizations are wrong. It just means that any generalization that claims that it is always correct for everyone everywhere is . . . wrong. One of us currently has a late Millennial (teenage) daughter who fits many of the generalizations of a technology-obsessed young person who communicates with her friends only through social media and texting—except that she prefers to read books on paper. So even when a generalization is usually correct, it can be off the mark on occasion.

One of the issues with social science research is that we can’t make claims with as much precision as physical scientists, such as chemists and physicists. While chemicals consistently have the same reactions with other chemicals, and apples on Earth always fall down rather than up, people are not so well behaved. Practically, that means that while we have great confidence in the accuracy of what we are saying, there will always be people who are exceptions to the general rule; there are always going to be some men who are shorter than most women, and some women who are taller than most men. To make sure people understand that the general rules aren’t true all of the time, many people automatically add qualifiers (what we call “weasel words”). These are words that make sure the reader doesn’t think that the authors are asserting that what they are saying is true for everyone everywhere in every circumstance forever and ever—words such as “sometimes,” “can be,” “may be,” and so on.

We are going to make a lot of generalizations in this book. These generalizations are backed up by data and will be accurate for most cases, though not necessarily all. But we don’t like weasel-words. So rather than inserting qualifiers in most sentences (which would make this book just as tedious to read as it would be to write), we ask that every time you see us making an assertion or generalization, you should remember that we are also saying the following:

This is true for many—we believe most—Millennials, under many—we believe most—circumstances, but isn’t true for all Millennials everywhere in every circumstance. And just because we can all think of a Millennial who doesn’t fit this description perfectly, that doesn’t invalidate the general principle.

While the generalizations are generally applicable to Millennials, there isn’t one universal solution for how you address any one Millennial in every single context. In most cases, the insights and advice are applicable regardless of how you interact with Millennials—understanding them is fundamental to interacting with them effectively, whatever your level. However, each recommendation isn’t universally applicable, so we have sections with specific recommendations for working with Millennials and for managing Millennials. The information is general. How you apply it is specific.

Much of What Is True About Millennials also Holds for Gen Xers and Baby Boomers

If you’re a member of the Millennial generation reading this book, we hope your response in many instances will be, “Yes! That’s so true. They get us!” And if you’re a member of an older generation, we expect your response in many cases will be, “Why are you saying this is just their generation? We asked for these things years ago! That’s what we said! That’s what we want, too!”

In reality, a lot of what makes people tick doesn’t change from one generation to the next. In our research on Millennials, we discovered many interesting characteristics that make this generation unique. But we also found that in most ways, Millennials’ expectations about work are strikingly similar to those of other generations. In many cases, Millennials are continuing a decades-long tradition of pushing organizations to change. We provide information about what Millennials want from work because the purpose of this book is to describe who Millennials are. While we occasionally compare Millennials and older staff where we think the contrasts or similarities are particularly interesting, an exhaustive comparison is beyond the scope of this book. However, we believe the majority of the recommendations we make for managers will be as effective for Gen Xers and Baby Boomers as they are for Millennials.

If we’re all the same, why bother to think about one generation at all, you might ask? Change is incremental, and what seemed like a massive shift when it was begun by Baby Boomers or Gen Xers can look like no big deal to someone who walks into the workplace with the change firmly in place. The benefit of a new generation entering the working world is that its members look at the workplace with a lens unclouded by past experience with the organization. When members of a new generation start working with us, their presence and new perspective can help shake us out of complacency, making us question some of the fundamental assumptions about why we do things the way we do. That’s a good thing.

A Brief Thank-You

While our names are on the front of the book, we wrote it with considerable assistance from a lot of people; we hope we thanked all of them in the acknowledgments. The work of many of our colleagues helped produce the data used here, and we are grateful to them for their contributions. It is incredible to us how many people were kind enough to give up their scarce free time to be interviewed, comment, help, read, review, and kibitz, rather than do something that was personally important to them. It is a gift for which we cannot thank them enough. So if you like what you find in the book, be sure to thank them because they helped make it that way. For anything you don’t like, complain to us!

One Last Thing Before You Start Reading

This book presents five core chapters that address stereotypes of Millennials we have found consistently around the world and two chapters about the implications for now (Chapter 6) and for the future (Chapter 7).

Our research revealed that, fundamentally, Millennials want what older generations have always wanted: an interesting job that pays well, where they work with people they like and trust, have access to development and the opportunity to advance, are shown appreciation on a regular basis, and don’t have to leave. They are focused on three key areas: the people, the work, and the opportunities. Hopefully, the knowledge gained from the research will help all of us bring their (and really, everyone’s) desires closer to being realized. Even if you follow our advice, we can’t promise that all issues with Millennials will miraculously disappear and you will have nirvana at work. However, we are confident that your organization will be a much better place in which to work, and the Millennials will be more engaged with their work and teams and more committed to the organization overall.