CHAPTER 2

NEEDY AND INDEPENDENT

Sean, a Millennial, is a first-level manager in a large organization. He’s being groomed to move up soon … if he can stop tripping himself up. He is an excellent employee. His boss appreciates the fact that he works lots of hours and is always available. He is an independent worker who is motivated to do his job well, clearly wants to contribute, and is willing to take on extra work and go the extra mile to make things happen.

But Sean is perceived as constantly needing affirmation. He frequently asks for feedback about how he’s doing and spends a great deal of time publicizing his work within the organization. He has made it clear that he wants to move up and is willing to do what it takes to get there. He wants to know precisely what is necessary to do that and exactly how long it will take.

Sean may be a good worker, but his boss perceives his constant need for affirmation and feedback as needy. Like Sean’s boss, many supervisors say that Millennials are needy because they want to know how they’re doing all the time. They want to be provided with very specific criteria for success. They want a map to tell them precisely how to get from here to there (with here being their current state and there being nirvana, both personally and professionally), and when they don’t get it, they are needy and clingy, wanting constant reassurance. At the same time, they are incredibly independent. They want coaching on how to achieve their goals, but they don’t want to be told what to do (which is how they often perceive advice).

Many of the complaints about Millennials being needy are focused in three areas:

• They want their parents involved.

• They want constant mentoring and assistance.

• They want frequent feedback.

MILLENNIALS ARE NEEDY, RIGHT?

Millennials are each needy in their own special way. Some have parents who hover; others want bosses to act as parents. Some want to be told every 10 minutes that they are doing well; for others, every half hour or so will do. At least that is what people say. Our data tell a somewhat different story.

Millennials Are Needy … They Want Their Parents to Be Involved in Their Work Life

Helicopter parents aren’t just for toddlers anymore—they are now well known in the business world.1 We heard about one high-potential Millennial who failed a drug test for his employer. The Millennial was informed about the results of the test, and a time was set for him to meet with human resources to talk about rehabilitation so he could keep his job. Before that meeting could take place, the Millennial’s mother went to his office and demanded that the HR person show her the drug test results, because she didn’t believe them. The HR person had to explain that it would be illegal to show her the results of the 27-year-old employee’s drug screen, even though he was her child. The mother kept insisting that she had to see the results, because clearly there had been a mistake!

Organizations around the globe have given us similar examples of parents intervening in their adult children’s work lives. It was clear to us that attitudes about parental involvement in adult children’s lives vary substantially by culture—and often within cultures. Even opinions regarding asking about parental involvement vary! In the United States and Europe, some considered our questions about parental involvement both inappropriate and unnecessary (why would anyone think parents would be involved, they asked us), although others were pleased that we were considering this issue because they had encountered it many times. People in India, the United States, and China thanked us for bringing up a topic that they struggle with daily!

While some managers have never encountered this before, parental involvement in one form or another is relatively common. Universum’s global survey found that a quarter of Millennials surveyed said that they involved their parents in their career decisions,2 and a 2007 Michigan State University study found that about a third of large companies had witnessed parents being involved in their children’s work lives.3 One area where Millennials’ parents are more likely to be involved is the job search and application process. According to the 2007 Michigan State study,4 40 percent of respondents said they had observed parents helping their child in the job search process: researching a company, complaining if the company didn’t hire their child, actually attending the interview, and so on.

Source: CartoonStock (www.CartoonStock.com)

We heard similar stories from many organizations. Common stories were about parents appearing in the workplace to negotiate their child’s starting salary or to complain that their child had been working too many hours. One manager told us that a parent directly phoned a supervisor to complain about a bad review. Another manager told us about an incident that happened with a new employee:

I hired a new employee who was scheduled to start in two weeks. That Monday (his first day at work), he didn’t arrive, and no one received a call from him saying where he was. He also didn’t appear on Tuesday. On Wednesday, he arrived and presented me with a note saying he had been ill. The note was from his mother.

The manager didn’t think it was appropriate for an adult employee to arrive with a note from his mother excusing his illness. As the manager said to us, this isn’t high school, and you don’t get an excused absence because your mother says you are ill. He attributed this behavior to Millennials being needy and wanting their parents to continue to take care of them.

While the stories make it sound as if many Millennials want their parents closely involved in their work, we didn’t find that to be true. With regard to parental involvement, the issue is really about the level of involvement. From what we found and heard during interviews, Millennials want their parents’ help but don’t want them closely involved. While we heard many stories about parents helping Millennials find their first job, we found that 90 percent of Millennials do not think parents should be involved in their child’s job interviews,5 and 85 percent of Millennials do not think an organization should send parents a copy of their child’s offer letter.6

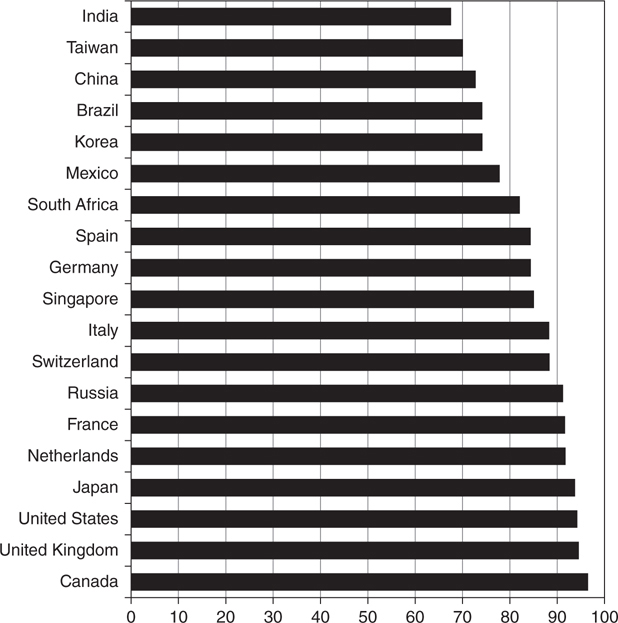

Figure 2.1 shows that Millennials in different countries don’t support parents receiving a copy of their child’s offer letter. In most countries, more than 80 percent don’t support the idea, though in India, Taiwan, China, Brazil, Korea, and Mexico, it’s less than 80 percent. Though few Millennials are clamoring for this type of policy (the vast majority of Millennials in all countries clearly don’t want parents actively involved in the hiring process), it is interesting to note the significant minority who want their parents involved: more than 1 in 5 in some of these countries and 1 in 10 in many other countries. Nonetheless, Millennials as a generation clearly are not in favor of parents’ actively participating in the hiring process.

FIGURE 2.1: Percentage of Millennials Who Don’t Support Parents Receiving a Copy of Their Child’s Offer Letter

Why, then, do people in organizations think most Millennials want their parents involved, when clearly it is a minority in all countries and a very small minority in most countries? This is a good example of how narratives about a generation are created. Someone who knows a few Millennials who want their parents closely involved can easily jump to the conclusion that such views are widespread across the entire generation. Though 10 to 20 percent of the population is a low percentage, it still means that thousands of Millennials want their parents involved. And it doesn’t take meeting more than a handful with this perspective for someone to reach the conclusion that most Millennials are like the handful they have met, even if those few are not representative of the generation overall.

Another area we hear complaints about is parents wanting to be involved in the performance review process at their child’s first professional job. For example,

A college hire who was with us for about nine months was having difficulty getting things done on time. Several coaching sessions were conducted between her and her manager. The manager told her the next time she missed an important deadline, he would have to write her up. When he scheduled a performance management discussion meeting with her, her mom came with her to the meeting. Of course, we told her that her mom couldn’t come to the meeting. The mom and the employee were shocked when we told the mom that she needed to leave or wait until the meeting was over to talk to her daughter. They didn’t see why the mom couldn’t be in the meeting with her daughter.

While we have heard from managers about parents they’ve encountered who wanted to know in detail about their children’s performance, most Millennials don’t want the organization to provide their parents with this information. In fact, 90 percent of Millennials do not support the organization sending parents their child’s performance review—let alone having the parents sit in on a performance discussion, as in the prior example.

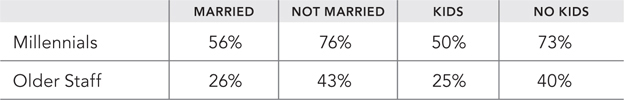

Millennials may not want their parents to take an active role in their work lives, but a majority of Millennials in all countries, except Japan, discuss their compensation with their parents (see Figure 2.2). In fact, a higher percentage of Millennials discuss their compensation with their parents than with their friends (47 percent) or coworkers (38 percent).7

FIGURE 2.2: Percentage of Millennials Who Discuss Their Compensation with Their Parents

One explanation for this pattern is life stage. We find that Millennials who are single and don’t have children are much more likely than those who are married or do have children to discuss their compensation with their parents (see Table 2.1). Millennials are more likely to discuss their compensation with their parents than are older employees who are in the same life stage. It will be interesting to see if this pattern holds when the Millennials are in their forties, as Gen Xers are now.

TABLE 2.1 Percentage of Employees Who Share Compensation Information with Their Parents

Who Millennials Live With

Part of Millennials’ openness in sharing compensation information with their parents may result from who they are living with. In the United States, there has been an increase in the number of Millennials who live with their parents or with other relatives after having finished university.8

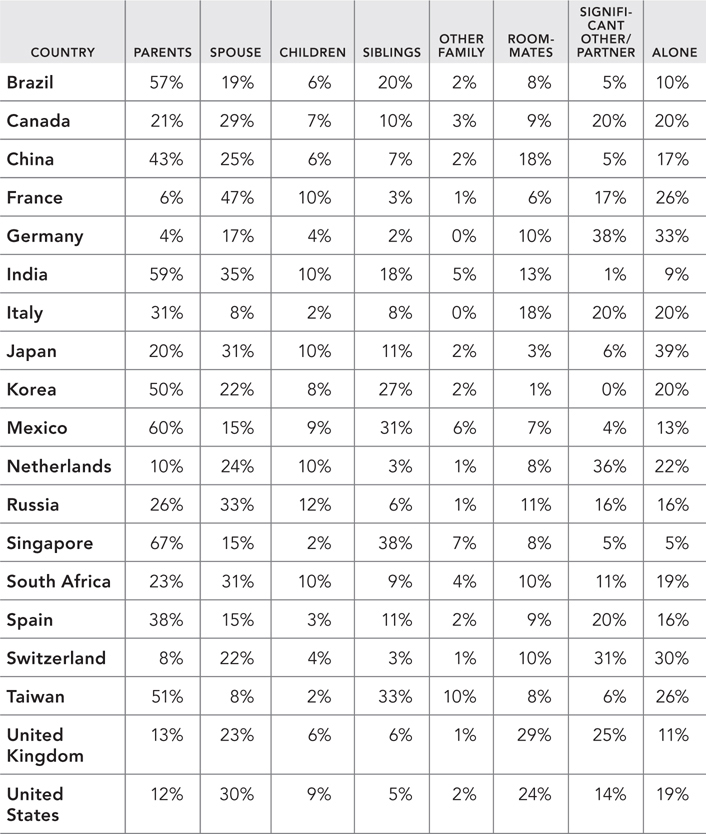

Globally, 28 percent of our sample live with their parents; it varies widely based on where the Millennials are from (see Table 2.2). The range across the globe is quite dramatic, from a low of 4 percent in Germany to a high of 67 percent in Singapore. There are many potential factors that cause adult employed children to live with their parents, including their salary and level of debt. But the level of economic development also appears to be a key contributor: countries with higher levels of national income are among those with the lowest rates of cohabitation with parents (Germany, France, Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada), while the less developed have among the highest rates (Mexico, India, Brazil, China).

TABLE 2.2 Who Millennials Live With (by Country)

Living with family is common, even expected in some countries, and is done as much for cultural as for economic reasons. For example, we heard from many single Millennials who could afford to live alone but who chose to live with their parents. We heard many Millennials who are married with children talking about how wonderful it is to live with their extended families. (Married Millennials living with their extended family seems particularly common in India.) These are people who have the means to live elsewhere if they wish to, so their choice clearly is a preference rather than an economic necessity.

In addition to culture, the cost of housing is likely a key factor in the choice to continue living with parents. For example, the high population density in Singapore leads to extremely high housing prices, making housing for young people starting off their careers quite expensive. (See Chapter 3 for more discussion about housing debt and how it may be affecting Millennials’ life and career choices.) Yet economics cannot explain all the differences in Table 2.2: the rate in Canada is nearly double that of the United States, even though its level of development is virtually the same. So cultural factors clearly play a strong role, even in countries with high national income.

![]()

While it is true that many Millennials live at home, from what we have seen, Millennials are generally no happier with their parents being actively involved in their work lives than their bosses are. In many cases, it appears that the parents are inserting themselves into their children’s lives despite being told not to interfere. For example, one manager in India told us about having issues with employees’ fathers and how she deals with them:

One employee of mine had to work late with her team on a project. She lives with her family (which is quite common in India) and told them she would be working late. The first night she worked until past 11 p.m. and then took a company car home. When she arrived home after midnight, her father was furious that she had come home so late and worried the whole family. She apologized and said that it was because her whole team was working late to meet a deadline. She explained that she would be working late for a few more nights and not to worry. The next night she got a call from the front desk at her office at 11 p.m. Her father had sent the family car for her, and she was expected to leave immediately. (Having a family driver is not unusual for the professional class in India.) She was embarrassed but left, apologizing to her team—and to me (her manager). The next day I received a call from her father, angry with me about his daughter having to work so late. I explained that if he didn’t want her to lose her job, he needed to allow her to work the hours she needed to work to be successful and to not interfere. He could certainly send the car but not pull her away from her work. I told him that I understood his concern for her safety, but she’s an adult and needed to be allowed to behave as such!

While Millennials may share a great deal with their parents, they don’t necessarily want them intimately involved in their work lives. And in many cases, the parental intrusion may be as embarrassing to Millennials as it is annoying to their bosses!

The Point

Millennials may want their parents to help them but don’t want them to be actively involved in all parts of their work. It is a good idea for organizations to provide information that anyone (including parents) can use to understand the organization. But it is not necessary—or even desired by most Millennials—for an organization to include parents in the hiring process and other aspects of the employment relationship.

Millennials Are Needy … They Want Constant Mentoring and Support

While Millennials don’t want their parents to take an active (interfering) role in their work lives, they do want support. Millennials perceive mentors as a support in their careers. They believe that a mentor will help them better negotiate the organization, plan their career, and open doors for them. Ninety-one percent of Millennials say they either have or want a mentor (the remaining 9 percent say they don’t like their current mentor or don’t want one).

Millennials’ desire for a mentor is not new, and this desire is just as common among the older generations. Almost a decade ago, the book Retiring the Generation Gap reported that Millennials (and Baby Boomers and Gen Xers):9

• Wanted a mentor.

• Wanted a senior colleague, an expert in the field, or a coach they choose themselves as a mentor.

• Wanted the mentor to focus on their career, their leadership development, or their job.

• Overwhelmingly wanted the mentor relationship to take place face-to-face (a relationship only over the phone or other electronic medium was not desired).

This desire for a mentor likely comes from Millennials’ belief that the purpose of the mentoring relationship is to focus on their needs as individuals, rather than on the organization’s or team’s needs. While supervisors can act as mentors, there is always the concern that supervisors will filter all advice, emphasizing what is best for themselves, the organization, or the team they manage. The same is not true of a mentor. Mentors may be thinking about how they can best help the individual to advance the ends of the organization, but their focus is still on the individual’s development and what will be mutually beneficial.

In addition to wanting mentors, Millennials want their bosses to provide support when they have too much to do. Almost three-quarters10 say immediate supervisors should go out of their way to help team members when demands become too difficult. What this means is that Millennials expect their supervisors to help get the work done when Millennials have too much to do. It is likely that expressing this attitude makes Millennials seem needy.

This wouldn’t be an issue if there weren’t a discrepancy between what the Millennials get from their supervisors and what they think they should be getting. While 73 percent of Millennials expect their supervisors to help, only 57 percent report that their supervisors do. So 16 percent perceive supervisors as not helping out as much as Millennials believe they should.

It is critical for organizations to pay attention to this discrepancy between what Millennials want and what they experience. Regardless of the actual levels of support, the gap between what Millennials believe supervisors should do and what they report supervisors actually do has a negative effect on their organizational commitment and engagement—and on the organization’s performance over time.

The Point

Like all generations before them, Millennials want mentoring in the workplace. They want someone to whom they can turn for advice and help in navigating the workplace. One out of every six Millennials also wants their supervisors to help more with the work than they do currently. Millennials will be more engaged if they feel that they are getting enough mentoring in general, and enough support from their manager in particular.

Millennials Are Needy … They Want Frequent Feedback

Millennials are often described as needy because they want frequent feedback. They want to know how they are doing on a regular basis. This desire is following the tradition of Baby Boomers and Gen Xers, who challenged their bosses and organizations to provide more and better feedback for employees. It is consistent with Millennials’ experience because many of them have grown up in a world where they received frequent feedback about how they were doing. In school and university, grades on papers, tests, and quizzes provided ongoing feedback. During nonschool time, feedback was frequent as well, from activities such as playing sports and interacting with friends (either face-to-face or virtually).

The world of social networking and texting has made it so feedback is typically available whenever an individual wants it. On Facebook, Instagram, and other social networks, people post pictures or notes about their personal lives and receive instantaneous “likes” and comments from their friends. Video games also provide constant feedback. Players win a race, rack up points, move up levels, etc. Anyone engaged in these kinds of activities receives constant feedback.

![]()

Joke

What do Millennials like to eat for breakfast?

Instant Feedback Loops

![]()

For some people, that feedback becomes as necessary as food. Then they get to the workplace. While there is assessment of performance at work, often feedback at work isn’t as constant, as immediate, or as positive as some would like. And sometimes it is missing altogether. For example, one Millennial told us about a project he was on:

Our team created a report for a VP who asked for it. He thanked us, but then that was it. None of us on the team were told what he did with it or what the client thought. We didn’t hear whether it was good or bad or how it could be done better in the future. It didn’t come up at our end-of- year performance review. It was like we had done the work and then had dropped it into a black hole. We assume the work had helped the company, but we have no idea how. How can we improve if we don’t get feedback? How can we feel motivated to do good work if we don’t know how it is used or connected with the organization’s goals? How can we feel appreciated if we aren’t recognized for good work?

Lack of feedback is a common theme we heard while speaking with Millennials. The Millennials we studied were either at work or involved with work in one way or another 8 to 12 hours a day, at least five days a week, and often on weekends as well. With all of those hours at work, how frequently do you think they get feedback? A few times a day? Every day? Every week? No. Most say they get it quarterly (26 percent), a couple of times a year (34 percent), or only once a year (17 percent). While 54 percent of Millennials would like developmental feedback monthly or more frequently (daily or weekly), only 23 percent say they get feedback that frequently.

© Ron Leishman, ToonClipart.com

Rewards or recognition are even less frequent. Millennials would like rewards and recognition for their good work either monthly (25 percent) or quarterly (31 percent). They say they generally get rewards and recognition annually (51 percent) or twice a year (22 percent). What all these numbers boil down to is that Millennials aren’t getting feedback, recognition, or rewards anywhere close to as frequently as they want, and that bothers them a great deal. They aren’t asking for feedback as frequently as they get it socially or when playing video games, but they do want it more frequently than they are currently getting it.

If Millennials appear to be needy, perhaps it is because their managers aren’t providing enough direction. Managers need to remember to set clear expectations for work and not assume anything. The management book The One Minute Manager11 points out how quick and easy it is to provide both recognition and feedback to subordinates. Doing so doesn’t have to take a lot of time. In fact, if it is done more frequently it is likely to take less time because the relationship is better established and there is less ramp-up time to the conversation. When feedback is provided immediately or soon after a relevant experience, the learning is more likely to stick—and you don’t have to spend extra time reminding both sides of the reason for the conversation.

The bottom line is that most Millennials are working with people 40-plus hours a week (plus work outside of standard office hours), and yet most receive feedback or recognition no more frequently than every few months. That doesn’t come close to meeting their needs. Millennials want relevant feedback about their performance frequently enough so they can act on it. If that makes them needy, then, yes, Millennials are needy—and with good reason.

The Point

Millennials want feedback about their work more frequently than they are currently receiving it. Managers should work on making sure that employees receive feedback at least every other week about the work they are doing. The door should be left open for employees to ask for feedback about their work if they are wondering how something went. The feedback doesn’t need to be extensive; often an acknowledgement of the work is enough. But managers do need to provide some sort of frequent feedback.

Millennials Are Less Happy than Older Generations

One reason Millennials may seem needy is that they’re not terribly happy. Less than a third12 say that they look forward to each new day at work, and they scored lower than all older generations on a variety of positive measures, such as being enthusiastic, active, excited, and inspired. They also scored higher than all older generations on a variety of negative measures, such as feeling scared, upset, hostile, afraid, irritable, etc. In short, Millennials aren’t particularly happy (see Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.3: Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)

It is unexpected to find that people in their twenties and early thirties are less happy than their colleagues in their forties, fifties, and sixties, because the research on what is called the “U-bend of life” suggests that people in their twenties and early thirties typically would be happier than their older colleagues.13,14 It is possible that this result is specific to our sample of professionals, managers, and executives. It is also possible that Millennials will have a different pattern over their life span. Researchers will continue to investigate the phenomenon.

![]()

NEEDY DOES NOT MEAN DEPENDENT

While Millennials want support, feedback, mentoring, and appreciation, that doesn’t make them dependent. They actually are being quite strategic. They think about what they need to be successful, and that’s what they ask for.

Millennials believe that they have no choice but to be independent actors in their careers. Baby Boomers grew up watching their parents (the World War II generation) in a work world characterized by long organizational tenure, secure pension plans, and organizational loyalty (employees staying with one organization for a long time were rewarded with steady, if slow, promotion). Millennials grew up in a different world altogether. They saw their parents (many of whom are Baby Boomers) deal with long hours, cutthroat competition, layoffs, wage stagnation, and insecure retirement plans. They witnessed the consequences of employees not having an independent attitude toward work. They saw dependence on an organization as an invitation to be taken advantage of, rather than something that is rewarded. As a consequence, they are independent: they want control over their work, don’t trust or defer to authority much, and want their work to be flexible.

Millennials Are Independent … They Want Control over What They Are Doing

One way Millennials demonstrate their independence is through their desire to control their work lives and careers. Though they might want coaching and mentoring, Millennials don’t want to be told what to do and don’t like being expected to execute like automatons. Following the path established decades ago by the Baby Boomers and Gen Xers, Millennials don’t see themselves as cogs in a giant machine; they see themselves as people who will shape their world to be what they want it to be.

For example, we were told about one Millennial nearing the end of a one-year rotation program during which she had three assignments in different departments to build her skills and capabilities so she could move up within the organization. As her program was ending, she was presented with a couple of different options for permanent roles. She didn’t like either of them, so she turned them both down. She didn’t accept the first because she didn’t think the executive responsible for the group understood her development needs. She declined the second because she didn’t think it aligned with her long-term career goals. She told the executive she was concerned that she didn’t have a future with the company because the opportunities she was presented with were not ones she felt would further her career.

As in this example, Millennials want to actively take control of their careers and work assignments. Ninety-nine percent of Millennials (and 99 percent of older employees) say that having control over work assignments is important to them. Unfortunately, Millennials don’t feel that they have control because they don’t believe they are told what they need to know for their work or their career. They ask questions but aren’t provided with the necessary information. In fact, a majority think their supervisors are not candid about why they are assigned specific work.

Millennials don’t think this is a general communication breakdown. They believe most supervisors don’t put a high priority on providing them with career-relevant information. While 61 percent of Millennials say they have enough information about how to accomplish their work related to the team’s goals, almost the same percentage (58 percent) say the reason for their particular part of the work was not clearly explained to them. From their perspective, supervisors are better at communicating when the information advances immediate objectives or team goals, and are less effective at communicating information when the information is more general or helps Millennials’ understand where their careers are going.

For example, a manager will be quite specific about the timeline for delivery of a project. But then five minutes later he might say that he will “have to see” when in the future the Millennial will be eligible for a developmental opportunity or promotion. The lack of specific communication regarding Millennials’ future with the organization is unsettling to them. There is a “trust us” factor implied by the interaction, yet the organization is providing no reason for Millennials to trust that their needs will be met.

Addressing Millennials’ desire for control does not have to be difficult. The key is that they want more control, not full control. They know it’s unreasonable to expect complete autonomy in deciding what work they will do and how to do it. They want more information about the choices for their assignments, and the latitude to decide how to get the work done. Where appropriate, they also want the latitude to decide what work they will be doing. All employees want to be able to influence what work they are doing and how their work is performed.

The Point

Millennials feel like they have little or no control over their careers, and they want more control than they feel they currently have. Managers can help improve employees’ feelings of control by providing more latitude for their employees to choose how and where work is done, by providing more information about why individuals are selected to do specific work, and by helping employees understand how their current work fits into their career plans more broadly.

Millennials Are Independent … They May Not Trust or Defer to Authority

Trust is a critical part of the workplace, but Millennials don’t have unwavering trust in the people above them in their organizations.15 This is not a new phenomenon and has been around for as long as young people have been challenging the norm of unquestioning faith in institutions and organizations. Part of the reason Millennials are so independent is that they aren’t particularly trusting in general and of authority in particular.

For example, we heard a story from an executive about a time he made a request of a Millennial. He couldn’t find one of his directors, so he asked someone two levels down in the organizational hierarchy to create a simple spreadsheet that day for a meeting with a senior vice president the next day. He made sure the Millennial didn’t have any questions about what was needed or when he needed it and went on with his day. The next morning he hadn’t received the spreadsheet, so he checked in with the Millennial and was told that he hadn’t started working on it yet. The Millennial’s manager (the direct report of the executive making the request) had been out the previous afternoon, and the Millennial was waiting on his approval. The Millennial didn’t believe he should do the work without the approval of his supervisor, regardless of the fact that it was his supervisor’s boss who had asked for it. The executive said, “I was gobsmacked first that he thought I was requesting versus assigning work, and second that he believed that my direct report needed to OK work I had assigned.”

Examples like this highlight an interesting pattern that we found: a majority16 of Millennials (and almost three-quarters of older employees17) don’t think that employees in general or they themselves in particular should do what their manager tells them to do if they can’t see the reason for it. This is likely rooted partly in a lack of trust. Millennials don’t have a great deal of trust in people at work, and even less in the organization they work for.

If Millennials don’t trust the people in charge, it is logical that they would be less likely to do what a manager or higher-level executive tells them to do without checking with their immediate manager first. Why would they do something if they can’t see the reason for it, don’t believe that employees have a duty to go along with the wishes of their manager (or their manager’s manager), and don’t believe that obedience to supervisors at work is desirable? Given the lack of trust and cultural shifts in the past 40 years, it makes sense that Millennials would not follow every directive given by their superiors within the organization.

TABLE 2.3 Millennials and Trust

38% of Millennials say that they trust their boss a lot,

while 8% say they do not trust their boss at all.

33% say that they trust the people they work with a lot,

while 4% say they don’t trust them at all.

28% say that they trust their CEO a lot,

while 10% say they don’t trust the CEO at all.

24% say that they trust their organization a lot,

while 7% say they don’t trust their organization at all.

The larger question is why this lack of trust exists. Leaders and managers sometimes forget that employees willingly follow the people they respect, think are honest, and feel treat them fairly. As Baby Boomers pointed out years ago and Gen Xers reiterated, trust in leadership does not come simply from leaders having a higher-level role than those they supervise. The leaders have to continuously earn their direct reports’ trust. And that comes from a combination of being honest, leading by example, demonstrating relevant knowledge, and giving people the room to succeed or fail on their own, with appropriate accountability, consequences, and rewards for performance. Often, employees don’t believe that their leaders and managers at every level embody these characteristics and behaviors.

Not trusting authority doesn’t mean that Millennials reject structure in an organization. In fact, a majority of Millennials think structure in an organization is important and say that they want there to be a clear chain of command and lines of authority (for more on this, see Chapter 1).

While Millennials want an organizational structure, they don’t want a boss who orders people around just because he or she has the authority to do so. Happily, a majority (64 percent) of Millennials say they don’t have that kind of boss. Unfortunately, 16 percent of Millennials say that their boss does behave this way—and 20 percent aren’t willing to say one way or the other. What this means is that 16 percent of Millennials are working for people they perceive as abusing their authority—and an additional 20 percent may be. So more than a third of Millennials may be seeing their bosses behave poorly. And even if the organization is addressing the supervisor’s bad behavior behind the scenes, Millennials care about how they are being treated more than they do about organizational initiatives that may address the problem eventually. When the bad behavior continues, it reflects poorly on the entire organization and its leaders.

The Point

Millennials are not wholly trusting of authority. Like older employees, they dislike working for people who exert their authority arbitrarily. Managers shouldn’t order employees around just because they can, regardless of the employees’ age. Managers should provide enough direction and information regarding required work to satisfy the employee. At the same time, if some Millennials don’t do their jobs, their managers should hold them accountable. No one, including Millennials, wants to pull the weight of colleagues who leave it to others to do their jobs for them.

Millennials Are Independent … They Want to Have Flexibility at Work

Millennials are quite independent in their work style. For example, 99 percent of Millennials say that it is important to have autonomy in getting their work done. Part of autonomy for Millennials is having the flexibility to work where and when they want to, while still being productive.

Millennials and Overall Trust

Millennials’ lack of trust extends beyond the workplace. When asked whether they believe that most people can be trusted,

• 32 percent of Millennials say people can be trusted.

• 24 percent say you can’t be too careful dealing with people.

• 44 percent say it depends.

In other words, only about one-third of the Millennials included in our research believe that people in general can be trusted, which is less than the 44 percent of older employees who say that people can be trusted.18

That number is supported by answers to other questions we asked about whether they trust the police in their own community (15 percent don’t), whether they trust the media (35 percent don’t), and whether they trust the banking industry (29 percent don’t).

When it comes to people in their communities, Millennials aren’t particularly trusting either. Less than 15 percent of Millennials say that they trust the people in their neighborhood or their community a lot. Further, only about a third19 say that they trust the people in their place of worship, and a paltry 13 percent say they trust those with whom they share their religious beliefs. (Older people are slightly more trusting on average.20)

Why are Millennials not particularly trusting of the people around them? Some have suggested it is because Millennials feel they themselves are not trusted because of how they are treated in the workplace. Our data show that Millennials who report feeling someone thinks they are dishonest are less trusting—of their bosses, their CEOs, their organizations, and the people they work with. Therefore, managers need to demonstrate to Millennial employees that they are trusted. To send that message, managers should provide them with flexibility, not micromanage them, and give them additional responsibilities.

![]()

For example, a focus group of Millennials in the United States was asked what bothered them about their work. Partway through the focus group, one particularly high-achieving Millennial got very upset. Why? Her boss wasn’t allowing her to go to her 7 pm yoga class. This was particularly upsetting to her because going to the yoga class was an important part of her life—it was how she managed her stress. When her boss said she couldn’t go, she said she would come back and work until midnight to “make up the time” she missed to go to her class. The work she was doing was independent of anyone else, so as long as she got it done, why did she have to miss something that was important to her? The perspective of the boss was that she was part of the team and needed to stay in the office without a break to show support for the team.

This wasn’t a generational conflict—the boss was a Millennial just four years older than she. This was a conflict over differences in perception, the need for autonomy, and beliefs about flexibility at work. The employee didn’t see why the hour of additional face time at 7 p.m. was necessary for the work; her boss thought it was. In the end, she didn’t go to yoga because she was concerned about the negative effect it would have on her boss’s perception of her as well as on her career prospects.

Millennials think that autonomy and flexibility mean working where and when they want so they can meet their personal needs—as long as they are being productive. Nowadays, working remotely using a computer or mobile device is easy. Because it is so easy and anyone can do it in principle, flexibility is perceived as just part of the job that everyone should have, rather than a perk to be earned. Older workers remember a time when leaving work early or working at home was a perk rather than an expectation. They often are annoyed by many smartphone-carrying workers—especially Millennials who are new to an organization—who believe that their work schedules should always be flexible, rather than seeing flexibility as a right that is earned.

Millennials disagree. They are part of a decades-long tradition of pushing organizations to increase workplace flexibility. They are independent workers who enjoy autonomy and don’t believe that spending time in the office indicates they are being productive. Given that 91 percent are contacted about work outside of work hours, clearly their bosses and coworkers don’t think that being in the office is required to get work done either. The frequency of contact about work outside of work hours means that they are already working flexibly to accommodate the organization’s needs (for more on this, see Chapter 1). So why shouldn’t they be able to work flexibly to meet their own needs?

When asked whether flexibility was important to them, Millennials overwhelmingly answered yes:

• 95 percent said that occasionally doing work from home (or wherever they want to be) is important to them.

• 96 percent said that occasionally shifting their work hours later or earlier to accommodate their personal life was important to them.

Flexibility does have some downsides. There is the issue of face time, which is important for learning, bonding with teams, and being seen to be productive. When people work flexibly, they have to show they are so productive and committed to the organization that they are available whenever necessary, even if they aren’t in the office. This can pose a challenge to those who want to have some uninterrupted personal time. But it appears that Millennials are willing to take on this challenge in exchange for the autonomy they enjoy and the flexibility to meet their personal needs.

The Point

Millennials want workplace flexibility. They want to have the latitude to be someplace other than at work, as long as it doesn’t affect their productivity. Managers should provide such flexibility as much as possible. Part of providing flexibility is having planning conversations with employees about deliverables so everyone is on the same page and working toward the same goals and timelines.

CONCLUSION: MILLENNIALS ARE BOTH NEEDY AND INDEPENDENT BECAUSE THEY’RE GOAL-ORIENTED

As you can see, the evidence shows that Millennials may be needy, but they are also fiercely independent. Millennials are both needy and independent simultaneously because they are focused on improving their work experiences and their career trajectories. They are needy because they realize they need assistance from those around them to improve. They are independent because they don’t trust those same people to make their best interests a priority.

One way Millennials are simultaneously needy and independent is in their desire to learn. Because they understand the work world they have entered and think that they are disposable to any organization, they strongly believe that they have to be continuous learners and can’t allow their skills to stagnate. They don’t expect to be able to stay in one job for 30 years and do the same thing over and over again (even if they wanted to). Instead, they believe that they have to keep growing, learning, and contributing more and different things to the organization. In fact, lack of learning opportunities is one of the reasons they will leave (see Chapter 5 for more information).

Given that Millennials are simultaneously needy and independent, the following sections describe some actions you can take to work more effectively with them, whether you are a team member, a manager, or a leader.

![]()

How Different Are Millennials, Really?

On average, parents of Millennials are likely to be more involved in their adult children’s work lives than the parents of older staff were. And when it comes to sharing information on compensation, even Millennials who are married and have children are more likely to share with their parents than are members of older generations. While parents are more involved in Millennials’ work lives, there is general agreement among Millennials, Gen Xers, and Baby Boomers that having parents very involved in their adult children’s work lives isn’t desirable.

Millennials are similar to older generations in their desire to have mentors, to get frequent feedback, to feel appreciated, to have control over their work, and to receive help when they need it. Millennials are slightly less trusting of most people they interact with at work and in their personal lives than are older generations.

![]()

Recommendations for Working with Millennials as Team Members

Some older team members worry that Millennials want them to act like parents. Not to worry—they don’t. Millennials have their own parents to worry about. What they would appreciate, however, is a helpful older mentor who can provide feedback on how they are doing and how to be more organizationally savvy. Millennials realize that their older peers have knowledge that they didn’t learn in school, and they appreciate it when this knowledge is shared. They won’t necessarily act as you’d like them to, but they do appreciate the information.

What Millennials don’t appreciate is being told that a task needs to be done a particular way because it has always been done that way. There is a big difference to Millennials between saying something like, “You might want to try it this way because I’ve found it saves me a lot of time and effort in the long run, but of course it is your choice,” versus “You should do it this way because this is the way it’s been done for a long time and it works well enough.” Remember, Millennials don’t like boring work and don’t want their time wasted, so how long a process has been used is not a good rationale for continuing it; they need to understand the logical reasons for it.

Millennials appreciate the opportunity to learn new things, which means that they are likely to want to learn about what you’re doing and help you with it. This is also why they appreciate positive mentoring. They understand that they don’t know everything, even though they may appear very sure of themselves; they realize there are many things they have to learn at work. In fact, they want to learn—it makes work more interesting and keeps it from getting too boring and routine.

One key to working with Millennials lies in striking the right balance between telling them what to do and being supportive of their independent action. Help them understand what they don’t know and provide them opportunities to learn from you. Hopefully, at the same time, you’ll also find some areas where you can learn from them. They do have considerable knowledge; thinking in terms of what you can learn from each other can improve your relationship. They are likely to be open to and interested in your input. So approach them as peers and appeal to their desire to learn new things, while also appealing to their desire to avoid doing things that waste their time and create rework. Acting superior is a surefire route to turning them off and creating conflict instead of allies.

Recommendations for Managing Millennials (and Everyone Else)

1. Don’t worry about managing their parents.

Most Millennials don’t want their parents to be intimately involved in their work life any more than Gen Xers or Baby Boomers do. Does this mean you will never encounter an intrusive parent of a Millennial? Unfortunately, you might. But if you do, you should treat it like any unusual, out-of-bounds behavior. All employees can have family members—whether parents, a spouse, or a sibling—who find ways to interject themselves into work processes where they aren’t invited. Employees usually don’t want them involved but may have a little difficulty navigating the situation entirely on their own. And even if they have it under control, some compassionate words and support from you can go a long way toward smoothing things over and minimizing any potential embarrassment the employee might feel. If you happen to be managing the very rare Millennial who thinks it’s perfectly fine for his or her parents to get involved in the workplace, the best thing you can do is clearly and unequivocally, but gently, explain the bounds of appropriate behavior.

2. Let them know how they are doing—frequently. Provide them with mentors and frequent feedback.

The simple truth is that most employees receive too little feedback in organizations today, regardless of their generation. Virtually every role in every organization would benefit from greater and more frequent feedback and guidance. You need to work toward that goal, not because it’s a good employment practice for your Millennial employees but because everyone, young and old alike, would benefit from more frequent and detailed feedback.

Therefore, as a manager, look for opportunities to provide feedback at appropriate times, not just at regularly scheduled intervals once a year or at the end of a project. Employees want both to know how they are doing and to feel appreciated on a consistent basis, not just when the work is done. If their work falls short of what you consider to be acceptable, they will respond much better if they are told in the moment when they have a chance to fix things rather than afterward, when the immediate opportunity to demonstrate improvement has passed. And if they are doing uninteresting work, you should take special care to let them know how they are doing and that their contribution is valued (see Chapter 1).

3. Provide support when things get tough.

Most employees want and need independence to do their work and don’t welcome being micromanaged. It is important to give all staff—including Millennials—the opportunity to succeed on their own, or else they will never develop the self-confidence needed to operate at higher levels within the organization. Yet independence and being totally cut off from all support are two very different things.

As a manager, make sure that employees have the time and space to work on and accomplish their tasks on their own. However, if you see that their work is subpar, provide them with support quickly so that they can correct their work and learn from their mistakes. Employees will not only benefit from learning from their mistakes; their self-esteem and business performance will be more shielded from risk.

4. Let them control as much as possible.

Control at work can be a tricky thing. People want to have a voice in determining what work they will do and choosing opportunities for the future. They also want to determine how and where they do their work. Of course, you can’t let people change every aspect of their work on a whim because there are too many proven processes that have to be followed in order for work to be done efficiently and effectively. However, in most roles, there is often room for individuals to control a great deal of how they do their work.

As a manager, giving your employees the freedom and control to determine parts of their job duties and work processes is a key to heightened engagement, commitment, and productivity. Communicate clearly and often with them about goals, timelines, and expectations for performance. Then give them the time, space, and autonomy to make decisions about work processes where there is some discretion in how things are done. Doing so will make them much happier and more committed to working for you in both the short and longer term.

5. Trust and be trustworthy.

Millennials might not be particularly trusting, but our data show that they will feel more trusting if they feel trusted. Give them some control over their work, listen to their thoughts, and provide the right kinds of support. Don’t disregard their ideas, and don’t micromanage them. Support them with the tools, resources, and colleagues needed to get the job done in an efficient and effective manner. Show that you trust them to get the job done.

Employees today have very sensitive lie detectors. They can sense when people are being inauthentic or dishonest. Though managers can’t always tell the complete truth, they need to be aware that people are sensitive to a leader or manager saying one thing at one point in time and then doing something different later. If there is a chance a communication might be perceived this way, it may be better to say nothing at all or explain that you can’t say anything rather than open yourself to the potential criticism that you weren’t entirely honest.

Five Points to Remember

1. Millennials want to control their lives and work as much as possible.

2. Millennials want to know what they need to do to be successful.

3. Millennials don’t want to be told precisely how to do everything.

4. Millennials are more likely to trust when they feel trusted.

5. Millennials don’t want their parents too involved.

![]()

Who Millennials Are and What They Want

Millennials:

• Don’t want their parents involved, even if they live with them

• Want mentors and support

• Want frequent feedback

• Want assistance where it is needed and expect people to pitch in to help

• Want to be appreciated

• Want control over what they are doing

• May not trust or defer much to authority

![]()