4

Putting Wisdom to Work: The New Role, Timing, and Purpose of Post-Retirement Employment

THE AEROSPACE CORPORATION has provided independent technical and scientific research, development, and advisory services to national security space (NSS) programs since 1960. Its workforce consists largely of highly qualified and experienced engineers, and its staffing needs vary significantly with the current contracts. The company's “Retiree Casual” program, established in 1985, brings retirees back to work part time. Employees can retire with full benefits as early as age 55, and after a gap of six months or more, return to work on a project basis for up to 500 hours per year. Most participants are engineers, but the program is open to all employees and includes contract managers and administrative assistants. In addition to their main roles, retiree casuals often serve as mentors, training program instructors, and recruiters.

For Aerospace retirees, the Retiree Casual program keeps former employees connected to their professions and their colleagues. For the company, the benefits are many. Phil Mathews, Principal Director for Talent Acquisition, states, “We are rehiring technical experts who understand our mission and are passionate to be able to continue to support it. The program also affords great mentor and knowledge sharing opportunities. We are proud to support this wonderful program.”

Scripps Health, founded in 1924, is a not-for-profit, integrated health care system in San Diego, California. Scripps offers employees a program to help them “downshift” into retirement by varying the cadence of their work. Employees with 20+ years of service can phase into retirement over a period of up to one year with full benefits. The program is available for all job categories, including nursing, hospitality, and leadership. Eric Cole, Vice President of Human Resources, explains the intent: “We value the diversity of our workforce, and for those who want to phase into retirement, we offer the structure to accomplish that. For Scripps, it's a win-win arrangement – we have the opportunity to facilitate knowledge transfer while assisting the participant with a gradual transition.” Workforce diversity is reflected in the fact that a significant percentage of new hires – 13.5% over the past two years – are over the age of 50. And the organization recaptures talent by hiring former employees who have stayed in touch through the Scripps Alumni Network.

CVS Health has long recognized the value of older employees, who comprise over 20% of their workforce. Customer demographics are changing and mature workers can respond and relate more effectively to older customers. Their “talent is ageless” initiative focuses on mature job candidates who are either reentering the workforce or changing careers. The company partners with federal, state, and local agencies and organizations to recruit, train, and place candidates who fit the needs of specific stores. New hires are often paired with mentors and have access to a variety of additional development and support programs for mature workers. Their innovative “snowbird” program has several hundred employees, including many pharmacists, relocating seasonally, just as their customers do, often from the Northeast to Florida for the winter.

Aerospace Corporation, Scripps Health, and CVS Health are just three of the growing number of organizations that have robust hiring and retention practices focused on utilizing the talent of older adults. Michelin North America, Mitre Corporation, and the U.K. National Institutes of Health also have longstanding phased retirement and retiree return programs. Pfizer's “Mentor Match” program connects employees of different ages and professional experience, and the senior leaders of the company mentor its fast-rising talent. Sodexo USA and Deutsche Bank have intergenerational employee networks that promote both cross-generational understanding and professional development. Deutsche Bank also forms intergenerational project teams.

What are these organizations up to? On one hand, they are protecting their talent supply in the face of both industry-specific labor shortages and the Boomer retirement wave. They are keeping experienced people longer, hiring them back as working retirees, and sharing knowledge and experience that would otherwise be lost to retirement. On the other hand, they are pioneering a future where a growing portion of the workforce will be older employees. They are developing programs and cultures that make them employers of choice for tomorrow's older and more multi-generational workforce.

Organizations that would follow suit may first need to escape some of the common myths and misunderstandings about work retirement (Table 4.1).

The Older Worker Payoff

Working in retirement is becoming the new normal. Today's retirees are working in record numbers. Seven in ten Baby Boomer workers expect to work past age 65, are already doing so, or do not plan to retire.1 If “retirement” used to mean the end of work, now we're at a tipping point: a majority of people will be continuing to work for a while after they retire, and it will become increasingly unusual for retirees not to work. However, retirees want to work differently – part time, in less stressful and more engaging roles, often in new occupations, often for themselves, and for a few years or as long as they like.

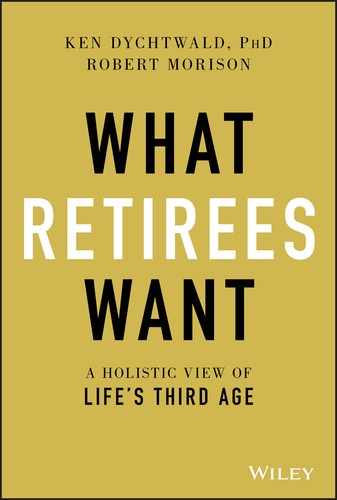

This trend carries profound implications for the workforce. The labor force participation rate of workers 65+ has risen to levels not seen since the 1950s (Figure 4.1). In prior decades, workforce growth was driven by the influx of young workers. In the last decade, however, older workers have accounted for virtually all workforce growth, and those age 65+ continue to be the fastest-growing segment of the labor force. This resurgence can prove a boon to employers across industries and government agencies that are facing shortages of skills and experience, as well as having difficulty hiring and retaining staff. It will not offset all the talent lost in the Boomer retirement wave, but it can mitigate the effects.

Table 4.1 Busting Some Myths About Work in Retirement

| Myth | Reality |

| Retirement means the end of work. People can't wait to retire, and they don't miss work when they do. | Pre-retirees say that retirement ideally includes some work, and the fully retired miss many things about work – most of all the social connections. |

| People work past retirement age only when they need the money. | Work satisfies many needs – psychological, social, and professional as well as financial. More people work in retirement because they want to than because they have to. |

| Retirement is a one-way street out of the workforce. | Retirees are working part time or cycling between work and leisure, and many return to the workforce after career intermissions. |

| Retirement work means more of the same. | Many retirees seek different lines of work and new employers – often themselves. |

| At retirement age, it's too late to launch a new career. | Retirees get additional education, reinvent their professional lives, return to early-career passions, and start new businesses. |

| Work in later life is hard and unappealing. | Working in later years is good for physical and mental health, and older workers are more satisfied with work and life than their younger counterparts. |

| Older workers can be liabilities. | Older workers are more experienced, committed, and engaged – productive and valuable in new ways. |

Figure 4.1 Age 65+ U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Around the world, the labor force participation rates of people 65 and older vary enormously. In most of Europe, the rate is in the (often low) single digits. But in South Korea, Japan, and New Zealand, it's 25% or more.2 Countries that are facing age waves and labor shortages are changing the incentives. In Japan, age 65+ people comprise a record 12% of the workforce, and three-fourths of Japanese age 60-64 are still working. Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's reforms to bolster the economy include raising the eligibility age for receiving pensions from the government and requiring employers to permit employees to keep working to age 65 if they want (however, workers still officially “retire” at 60 and return at lower salaries). In Germany, the age 65+ participation rate is about 8%, but the working-age population is projected to shrink over the next 20 years. The country is also gradually raising the federal retirement age, and its “Initiative 50 Plus” provides training to older people, pairs them with unemployed young people as a mutual learning opportunity, and temporarily subsidizes the salaries of older people who take new jobs at lower pay.3

Working retirees (and older workers generally) bring experience and often need less training. They bring social awareness and skills for engaging with customers, including older ones. They have higher engagement levels, which translates into productivity and customer satisfaction. They tend to be loyal rather than job hop. Many are motivated to share their experience and give back to an organization, including by mentoring younger colleagues. And they bring special management skills, as a recent MIT Sloan Management Review article points out: “While younger managers prefer narrower, more technical approaches, older ones tend to work through others and focus on the big picture.”4

Chip Conley shares more of his work-in-retirement story: “In early 2013, I returned to the workforce in my mid-50s as a senior executive with tech start-up Airbnb. I was twice the age of the average employee and was reporting to co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky, who was 21 years my junior. What I lacked in DQ (Digital Intelligence), I made up for in accumulated EQ (Emotional Intelligence). The mutual mentoring I offered and received turned me into what I call a ‘Modern Elder,' someone who marries wisdom and experience with curiosity, a beginner's mind, and a willingness to learn from those younger.”

These “elder” cognitive skills are valuable in the workplace. Dr. Charlotte Yeh, Chief Medical Officer at AARP Services, Inc., explains: “As you age your brain doesn't process information as fast. You might not remember everything and you're not as quick as you once were. But on the other hand, you're a better problem solver. You have better vocabulary, better pattern recognition, better executive function. You get wiser and have more of the creativity that comes from experience.” Chip Conley adds, “There's growing data showing the value of cognitive diversity on teams, and the best cognitive diversity comes from age diversity, more than diversity of gender, ethnicity, or background.”

Encore.org founder and CEO Marc Freedman makes a similar and timely case for the value of older workers: “We keep hearing that technology is going to render older people obsolete. But the more that artificial intelligence encroaches on traditional roles, the more it brings to the fore a truism: Qualities from the heart, like empathy and the ability to connect, are essential to nearly every role in society. And those are the qualities that peak as we get older.”

To tap into this growing and valuable workforce segment, employers must adjust practices ranging from work arrangements (e.g., to offer the part-time or project work most retirees prefer) to compensation and benefits (e.g., to mesh with health benefits retirees may already have). They must avoid the pitfall of taking older workers for granted, instead offering them opportunities to learn and do new work. They should offer employees options for phasing into retirement (thus retaining talent longer), stay in touch with their retirees (as a source of labor and referrals), and welcome retirees with engaging work and flexible arrangements. We find that many organizations are aware of the demographic shifts and feel the pressure of staff and skill shortfalls. Yet they have not made the needed adjustments to be employers of choice for working retirees.

Why People Work in Retirement

Four powerful forces are behind the rise in older workers:

- Longevity. Increasing life expectancy has produced retirements that can last 20 or 30 years or more. That's a long time to fill, and retirees are filling more of it (especially the early portion) with the stimulation of work, and in the process keeping their retirement savings topped up.

- Pensions. That topping up is increasingly necessary since most employers have eliminated guaranteed lifelong defined-benefit pensions. The burden of funding retirement has shifted from employers more to employees, and the relative role of Social Security is declining, so more retirees rely primarily on their 401(k) and personal savings accounts.

- Economic uncertainty. The 2007–2009 recession and its aftermath depressed employment and ate into the assets (especially in housing) and retirement savings of many. It served as a wake-up call for those who had insufficient savings and would find it financially unsustainable to retire without some employment income.

- Revisioning later life. It's not just about the money. The Boomer generation has looked at things differently and changed the norms throughout their lives. As they retire, they see their later lives as active on many fronts, full of purpose, stimulation, social interaction, and fulfillment, including from work. As more of them work in later life, retirement itself is transforming.

Longer lives mean lengthier retirements and potential difficulty funding them. So more people are questioning whether a 20+ year retirement without work is practical, affordable, or desirable. They are giving work an important place on their retirement agendas and reaping a variety of rewards – financial, social, physical, and psychological. As one retiree put it, “Not working, that was for my parents' generation. I can't imagine not doing anything for 30 years. Nor could I afford to.”

This trend will likely not reverse any time soon. While many current retirees feel secure in their Social Security payments and may have employer pensions to fund their retirement, younger generations anticipate the need to rely primarily on personal savings and employment income in retirement.5

Chip Conley makes the case for working in retirement: “We survey our Modern Elder Academy alums, and people say it's foolish to retire, for three reasons. One, it accelerates your mortality rate. Two, there's the financial wisdom of working longer. As Stanford economist John Shoven noted, it's hard to finance a 30-year retirement on a 40-year career. Three, people doing hard physical labor are usually enthusiastic to get into retirement, but in a knowledge-worker world people can use their skills much longer, and therefore stay vital and engage with life longer.”

Of course, people who reach their sixties with insufficient retirement funding will need to work in retirement out of financial necessity. For the majority of retirees, however, the nonfinancial benefits are just as important. Many retirees are shifting from full-time, often workaholic careers to part-time work on their own terms in roles they enjoy. Compared to their earlier careers, people describe their retirement work as far more flexible and fun, and far less boring and stressful.

In surveys of the general public, and even of pre-retirees in their fifties, respondents anticipate that they'd work in retirement primarily because they need the money.6 However, when actual working retirees are asked about their reasons for working, they paint a different picture. Money counts a lot, but not as much as staying mentally sharp. Other common motivators include maintaining social connections, staying physically active, challenging oneself, and avoiding boredom. Four in ten working retirees say they can't imagine not working.7 Retirees who work feel more stimulated, connected to others, and proud of their accomplishments. They can achieve satisfying work–leisure balance, pursue personal and entrepreneurial ambitions, and use work in retirement as the chance to give back. Most telling, more people say they work in retirement because they want to than because they have to. Those who choose to work in retirement can significantly improve their finances, but work has great value beyond the paycheck.

Retirees know that staying active and engaged is healthy. Eight in ten agree that work helps people stay more youthful, and two-thirds feel that, when people don't work, their physical and mental abilities decline faster. A study of 83,000 older adults across 15 years found that people who worked past age 65 were about three times more likely to report being in good health and about half as likely to have serious health problems, such as cancer or heart disease.8 As one retiree put it: “If you don't work, you shorten your lifespan. You get old faster.”

Social connections also prove very important. When we asked non-working retirees what they miss most about work, they said it's the social connections in the workplace. Dr. Charlotte Yeh underscores the point: “We did some focus groups on loneliness among retirees. In one group of men, they all said when they were working they had colleagues, friends, and were very active. When they retired they expected to continue to have the same network of friends. But the door came down and it wasn't the same anymore.”

For many, work in retirement kindles a new or renewed sense of purpose through doing good and mentoring others. There are matchmakers to help. Encore.org taps the talent of people 50+ who want to contribute the experience they've accumulated over the years to do good. The Encore Fellows program gives participants paid positions – usually half-time for a year – using the skills from their working lives on behalf of non-profits and social enterprises. Major organizations embrace the program; a few even offer every retirement-eligible employee the chance to serve in a company-funded fellowship. The Encore Physicians program, supported by Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefits, places retired physicians in part-time, paid roles in community health clinics.

Those who are especially happy working in retirement often cite one of four reasons:

- They returned to early-career roles or passions – “I get to be an engineer again.”

- They returned to being individual contributors without the stress of managing others – “No more Monday meetings and weekly reports.”

- They can give back to their organizations or professions – “I enjoy sharing what I know with the next generations.”

- They can start their own business – “I'm working for myself and building something new.”

Another retiree we spoke with offered the best scenario for working in retirement: “When you look at people inspired in their later life work, you realize it is because it's their passion. They don't consider what they do a job – they consider it their life.” Mike Hodin, PhD, CEO of the Global Coalition on Aging, put it in a nutshell: “What do retirees want? There are lots of answers, but many simply want a job. They want to stay in the game.”

How People Work in Retirement

Retirees want to be able to mix work with other pursuits. So most working retirees put in the equivalent of about half time. In terms of preferred work patterns, they fall into two almost equally divided camps. A little over half prefer working part time on a regular basis, which has the advantages of predictability and regular income. But nearly as popular is cycling back and forth between work and leisure. That can be on a seasonal basis, leaving time for special pursuits (camping in summer or skiing in winter). Or it can involve project-based work, which is a good fit for many kinds of organizations.

Some find ways to do project work mainly from home. Work at Home Vintage Experts (WAHVE) is a staffing agency for companies seeking experienced contractors for projects in accounting, human resources, and insurance. They seek to place “vintage professionals who have left the traditional workforce to phase into retirement.” A variety of websites, including Upwork.com, Freelancer.com, and Guru.com, match companies with project-based workers of all ages. AARP does regular research on what jobs are available where for those over age 50, and they provide online resources, including a job board, for employers and employees alike.

Many see retirement as a chance to try something new or even pursue careers they were unable to explore when working full time. Carol Thomas told Next Avenue how her lifelong love of photography turned into more than a hobby in retirement. After retiring as CEO of Education Northwest in Portland, Oregon, she began taking photography classes. Now photography has become her “second act,” and she volunteers for Pro Bono Photo, a group that provides nonprofit environmental groups with free professional photography.

The majority (60%) of working retirees we surveyed said they stayed in the same or a similar line of work, but that leaves plenty who switch. When retirees choose to stay in the same line of work, they say it's because they're good at it and they know how to balance it with the rest of their lives. Few feel confined to their careers for financial reasons. The top reasons retirees move to a new line of work are all about flexibility and fulfillment: work schedule, enjoyment, and the opportunity to learn new things or pursue a passion or interest. Making more money is seldom the motivation for a switch. Those who take breaks from work at the start of retirement are more likely to change line of work, perhaps because they had the time to explore new options.

Retirees often welcome the chance to work for their pre-retirement employers on a part-time or project basis – providing the employer with experience, continuity, and opportunities for knowledge exchange. Many are motivated to give back to their employers, sometimes by lending their experience to business improvement projects, sometimes by training or mentoring younger coworkers. Others seek ways to advance their professions more generally. Law enforcement executives such as chiefs of police tend to retire at relatively young ages, and it's common for them to then join advisory or technology firms devoted to improving law enforcement work.

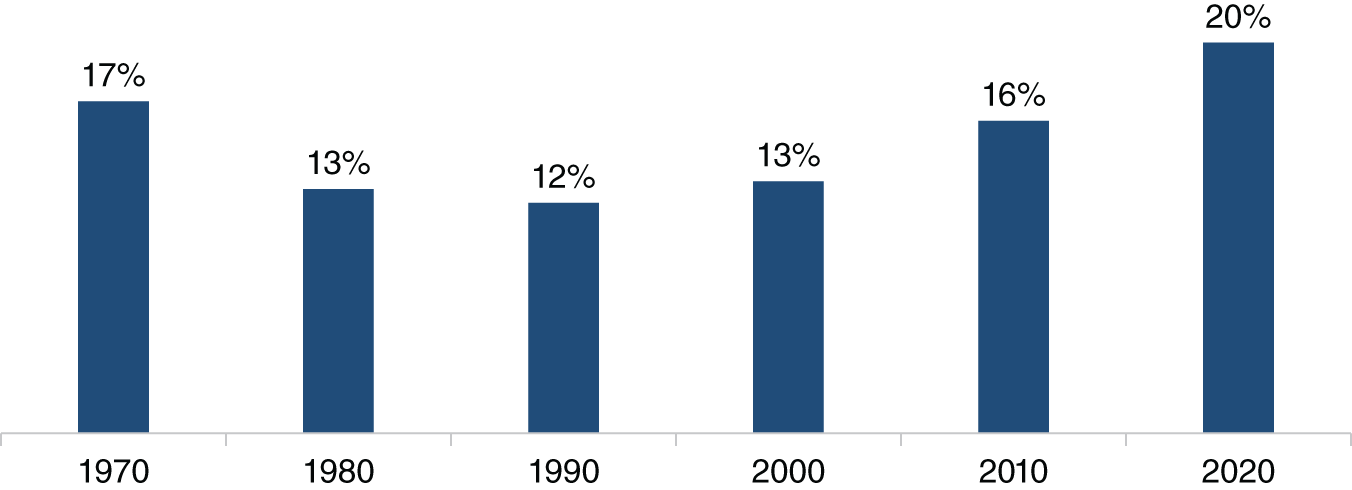

About one-quarter of workers over the age of 65 are self-employed as independent contractors or business owners. They're three times more likely to be working independently than younger workers are, and their overwhelming reason is the ultimate flexibility of working on one's own terms. Only 14% said they're on their own because they couldn't find employment (Figure 4.2).

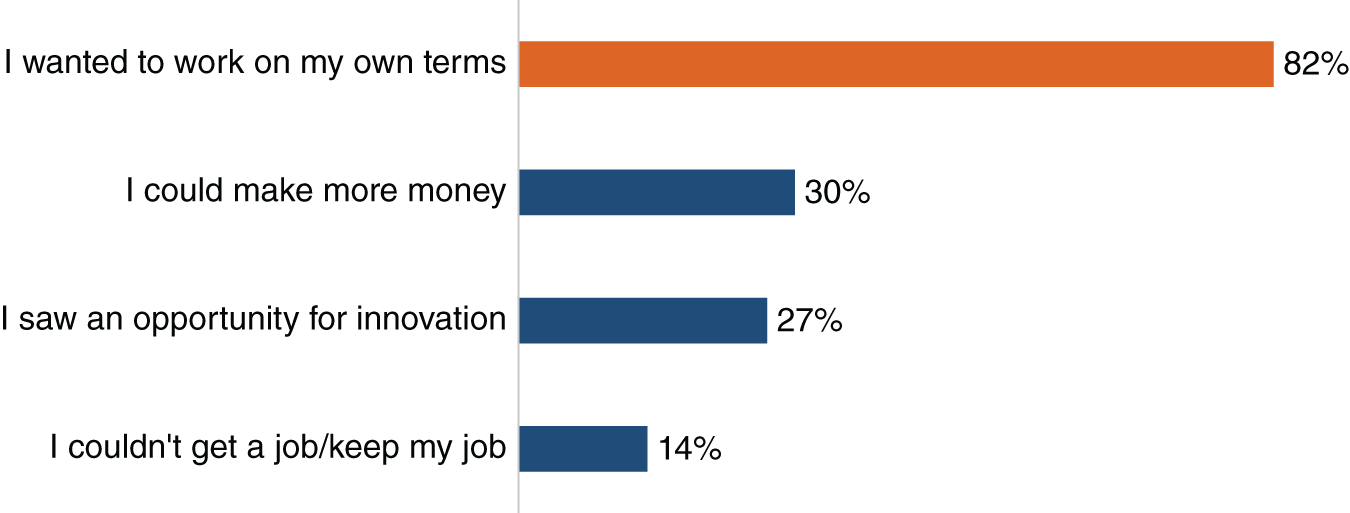

When we say “entrepreneur,” many may think of a Silicon Valley 20-something. The reality is that older people – with greater experience, business connections, and financial resources – consistently outpace younger ones in entrepreneurial activity. One-fourth of the new business owners (defined as those who have paid employees) in 2018 were 55 or over. That's up from 15% two decades earlier (Figure 4.3). And a 60-year-old startup founder is three times more likely to succeed than a 30-year-old founder.9 Lori Bitter, author of The Grandparent Economy, points out that financial services firms are recognizing this trend: “American Express, for example, has a small business group that works with entrepreneurs, and it's very age inclusive. Their newsletters and ads and services all support people who are starting a business later in life.”

Universities have recognized the need and opportunity to help experienced professionals prepare for and launch their “second act” careers. Stanford and Harvard have year-long programs. Notre Dame and the Universities of Texas and Minnesota have followed suit. Harvard's Advanced Leadership Initiative calls itself “a third stage in higher education designed to prepare experienced leaders to take on new challenges in the social sector where they have the potential to make an even greater societal impact than they did in their careers.” These are year-long programs in conventional academic format. Shorter and much less expensive programs focused on social purpose and nonprofit roles are offered at Union Theological Seminary in New York City and University of Connecticut. Through Encore!Connecticut, professionals transition their skills and experience into managerial and professional roles – paid or volunteer – in the nonprofit sector. The program combines coursework with a two-month practicum in a nonprofit organization.10

Figure 4.2 Why People Start Businesses in Retirement

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations

Figure 4.3 Entrepreneurs by Age

Source: Kauffman Indicators of Entrepreneurship, 2018 National Report on Early-Stage Entrepreneurship

Employers are also playing educator. Goldman Sachs, Deloitte, Credit Suisse, and HP Enterprise offer “returnship” or “career reboot” programs that help people who have been out of the workforce for a while get back up to speed. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles has a physician reentry program. CloudFlare has 4-month paid internships for professionals returning to the workforce after taking time off for caregiving. Paul Irving, JD, chairman of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging (as his encore career), has a recommendation: “Training for an encore career is an experience that we should provide to as many people as possible in very different ways. This is something that should be available on high school campuses at night and certainly in community colleges throughout America.”

The Life Cycle of Work-in-Retirement

For some, the essence of retirement is to be free of work. They may have accomplished their career goals, be financially secure, have a slate of retirement activities planned, or want to be rid of the responsibility and stress of holding a job. Others may not have enjoyed their work and have been counting the days until retirement. Those at the opposite end of the spectrum can't imagine not working. They enjoy their work, have gotten good at it, and are passionate about it. This category includes high proportions of artists, entertainers, writers, educators, craftspeople, and those who build things, including family businesses.

For the large portion of retirees in between, part-time work can be an attractive option, especially early in retirement, and they commonly take a break from work before returning to it. Employers who understand this common life cycle of work in retirement are able to engage retirees in the right ways at the right times, including helping them phase into retirement and then back into the workplace.

Many people who know they want to work in retirement give themselves a head start beginning several years in advance, and their preparation naturally intensifies as retirement approaches. They talk with friends who are working in retirement, network with professional colleagues, consult with their employers about opportunities to continue working in retirement (or phasing into it), perhaps get some additional education or skills training, and put together a personal “business plan.” Some engage career planners when approaching retirement. The Retirement Coaches Association and the National Career Development Association help them find certified career counselors, and companies like The Muse offer quick access to profiles of coaches.

About half of working retirees told us they took a significant break from work when they first retired. They wanted to take time to relax, recharge, give “not working” a try, take extended vacations, get some projects done, and perhaps do some of the work-in-retirement preparation that they'd postponed. The length of these “career intermissions” varies widely, but most are more than six months, and the average intermission is over two years. Those who take intermissions tend to enjoy them as sabbaticals – chances to escape the responsibilities and stresses of busy careers – more than filling them with new responsibilities.

As the standing joke has it, “I failed retirement and went back to work.” One working retiree gave us a different spin: “It took just three years of retirement before the bucket list started getting empty.” Returning to work after an intermission may require some catching up with industry changes, technologies, or everyday methods and skills. But the intermission has probably clarified what work retirees want to pursue and how much they want to work. Some will job hunt, some move into jobs that have been waiting in the wings, and some take the plunge to work for themselves or start businesses. Retirees tend to have the flexibility and perspective to reengage with work on their own terms.

Almost all working retirees decide at some point to “finally retire.” They may have met career goals, solidified their financial security, encountered health problems, or simply decided that they were ready for more leisure and other activities. When they do finally fully retire, they may experience a reduced version of the culture shock people feel when retirement means quitting full-time work “cold turkey.”

Workforce Ageism, Skills Obsolescence, and Other Barriers

There are, of course, challenges to reentering the workforce, especially following a lengthy career intermission. When older workers seek employment, it can take nearly twice as long to find a job as younger workers take.11 Perceptive employers can recognize the hurdles and help working retirees over them.

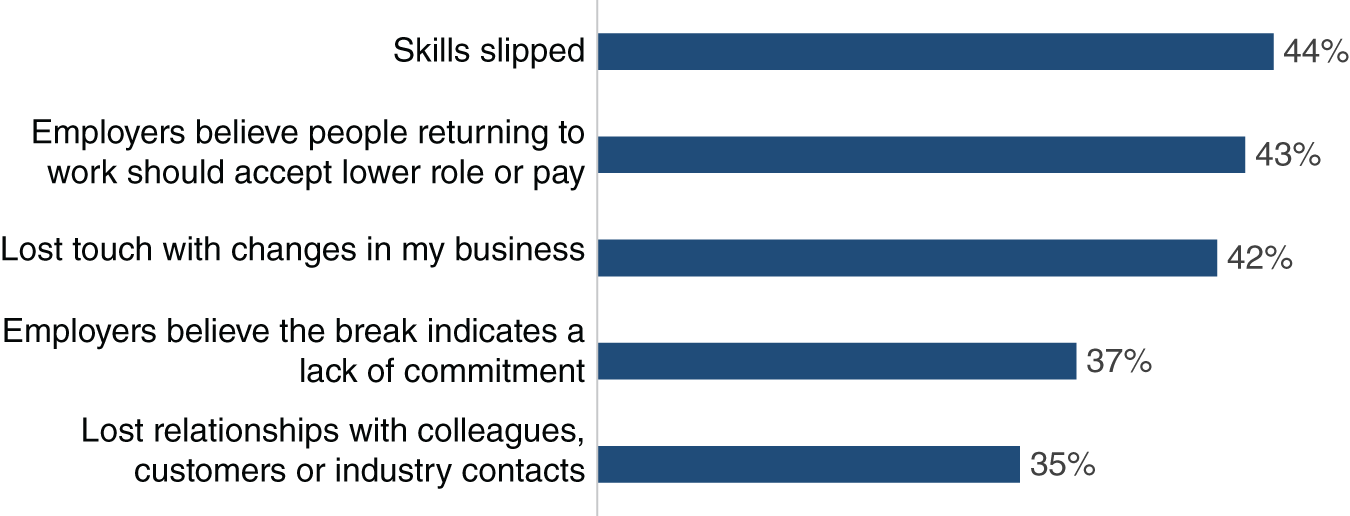

Retirees find the biggest issue to be skills slippage (Figure 4.4), and 40% of Boomers say they are keeping their skills up to date to ensure they'll be able to continue working in retirement if needed.12 Other barriers include employer assumptions regarding role and pay, losing touch with business trends, and lost relationships with key contacts.

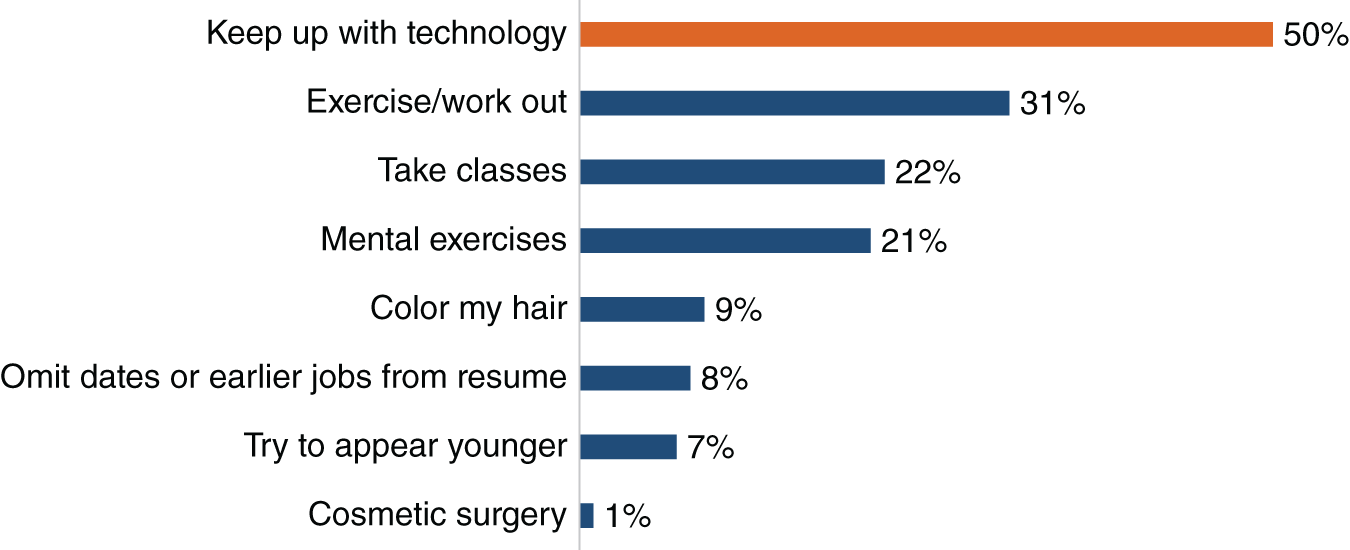

We asked working retirees for their advice to pre-retirees who are considering employment in retirement. Three-fourths recommend being open to trying something new and being willing to earn less in order to do something you truly enjoy. We also asked what they would do to make themselves more employable (Figure 4.5). Keeping up with technology tops the list, followed by physical and mental exercise and taking relevant classes. Those are all deemed more important than cosmetic changes to oneself or one's resume.

Figure 4.4 Challenges Reentering the Workforce

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations

The biggest barrier retirees face, however, is more systemic. Ageism in the workforce has been illegal since the Age Discrimination Employment Act of 1967, yet it remains prevalent. A 2018 AARP study found that nearly two in three workers aged 45 and older have seen or experienced age discrimination on the job. And a study from ProPublica and the Urban Institute found that about 56% of Americans over age 50 have faced or could face “employer-driven” job loss.

Figure 4.5 What Working Retirees Would Consider to Remain Employable

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations

Sometimes the problem goes public. Until 2018, Facebook was enabling companies to post job advertisements based on the user's age. ProPublica published an investigative piece on how IBM had pushed out upwards of 20,000 older workers. But more often ageism happens behind the scenes. And there's a fuzzy line between outright discrimination and subtle bias, as Chip Conley writes in MarketWatch: “One paradox of our time is that baby boomers enjoy better health than ever, remain vibrant and stay in the workplace longer, but feel less and less relevant. They worry, justifiably, that bosses or potential employers may see their experience and the clocked years that come with it as more of a liability than an asset.” For all the reasons we've discussed, such attitudes toward older employees are extremely short-sighted.

Four Types of Working Retirees

We've described how people work in retirement for a variety of reasons and in a variety of patterns. Looking across them, our research has revealed four distinct types of working retirees, each with different attitudes, priorities, and ambitions for work and its place in life (Figure 4.6). Recognizing and appreciating these segments can help organizations be realistic about the variety of older employees and how to attract and retain them.

Builders

Builders keep right on working and achieving in retirement. Work is an important part of their identity, and they feel at the top of their game. Working in retirement provides the opportunity to use their expertise, try new things, and accomplish more. Builders have the highest levels of engagement and satisfaction (84%) with work. They are energized by work, see it as a way to stay mentally and physically healthy, and feel they would be bored if they didn't work in retirement. They are proud of their accomplishments and most likely to consider themselves workaholics, even in retirement.

Figure 4.6 Segmentation of Working Retirees

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations

Builders are also the most likely of the segments (39%) to be self-employed and to have started their own businesses in retirement. They tend to stay in the same line of work because they're good at what they do. They do the most planning for working in retirement and are least likely to take a significant career intermission. Demographically, Builders are more likely to be men (61%) and highly educated. They have the highest levels of income and assets, and they are most likely (54%) to feel financially prepared for retirement. Their soundtrack for working in retirement is Rod Stewart's “Forever Young.”

Contributors

Contributors find ways to give back, often by working for nonprofits. Retirement is a whole new chapter of working life and an opportunity to do good. Work is a means to the end of helping others, the community, or worthy causes, and those results constitute much of the reward of working. Contributors are very engaged at work and have a high satisfaction level (75%). They also tend to feel happy, connected to others, and content in their lives. They feel that giving back in retirement should be the norm.

Most Contributors change jobs in retirement to pursue a passion or interest. Four in ten work for nonprofit organizations, and they are also most likely to volunteer significant amounts of their time. Many have prepared for working in retirement by volunteering in a relevant field, taking classes, and networking with colleagues or friends. If they take a career intermission, they return to work because they want to be making a meaningful contribution. Demographically, the majority (53%) of Contributors are women. They tend to be well educated and comfortable financially. Their soundtrack for working in retirement is Frank Sinatra's “The Best Is Yet to Come.”

Balancers

Balancers work in retirement largely for the activity and social connections, and without letting work dominate their lives. They may need the extra money, but work–life balance is the top priority. They feel that they have paid their dues and that retirement is their time. They want enjoyable work, flexible schedules, and likeable colleagues. They are relatively satisfied (67%) with work, but not highly motivated to put in extra effort, and they don't feel a strong need to give back. They tend to feel happy, content, and relaxed about life in general.

Balancers are most likely to work part time without changing lines of work. They did little to prepare for working in retirement, and if they take career intermissions, they return to work because they missed their work friends and relationships, or because they simply found a good opportunity. Demographically, Balancers' gender split is 50–50, and they are most likely to be married. They are somewhat less educated than average but have above average income and assets. Less than half (42%) feel financially prepared for retirement. Their soundtrack for working in retirement is the Eagles' “Take It Easy.”

Earners

Earners keep working primarily to pay the bills, and with less satisfaction than the other segments. They're the least likely to say they'd keep working if they won the lottery, or that they'd be bored if they didn't work. Earners express more frustration than other working retirees do, including over ageism, lack of training, and feeling irrelevant or unmotivated. They may feel like they got a raw deal – that retirement was supposed to be leisure time. They have poorer general health and miss more days of work due to personal illness than other retiree workers.

Earners most often work for an organization other than they retired from. Whether they pursue a different or similar line of work, their priority is the income. They did little preparation for working in retirement and often regret that they didn't plan better. Those who take a career intermission return to work when they need the additional income. Demographically, they are slightly more likely to be female (53%), most likely to be unmarried, and have less than average education. They have the lowest assets and income, and are least likely to have guaranteed pensions. Almost none feel financially prepared for retirement. Their soundtrack for working in retirement is Simon and Garfunkel's “Bridge over Troubled Water.”

Employers are not likely to attract a lot of Builders because they are fewer in number and tend to work on their own, but their expertise and ambition can both be very valuable. Contributors will gravitate toward roles that involve serving customers or colleagues and sharing their experience. With Balancers, the employer should keep working arrangements clear and respect how these employees separate work from the rest of their lives. Organizations employ a lot of Earners (of all ages). Their productivity can best be maintained by keeping the work engaging and by regularly recognizing their contributions.

How Employers Can Engage Working Retirees

Businesses, nonprofits, and other organizations that want to make the most of the retirement-age workforce – to alleviate labor and skills shortages, improve business performance, and promote knowledge and experience sharing – must be programmatic in their approach. It will make little difference to hire individual retirees here and there. You need to engage them at scale. The process begins with getting in touch with the demographics of an organization's workforce. What is the age distribution? Is a retirement wave under way or impending? What key roles and skills may be in short supply? And what are the options for retaining and replenishing the supply of talent?

We started this chapter with examples of programs at progressive organizations. Here we briefly review five key programs for engaging, retaining, and leveraging the experience of older employees and working retirees. You may devise local variations that fit your employees, culture, and need for experienced labor.

- Phased Retirement programs, like that at Scripps Health, offer reduced responsibilities and flexible role and work arrangements as employees approach retirement. Forty-two percent of pre-retirement Boomers envision phasing into retirement, yet only 29% say their employer offers any sort of phased retirement arrangements.13 Phased retirement enables the organization to keep talent longer, and the individual to give partial retirement a try instead of quitting “cold turkey.” The most effective programs also incorporate knowledge exchange to understudies or teams of colleagues.

- Retiree Return programs, like Aerospace Corporation's, tap into the large talent pool of qualified retirees to meet staffing and skills needs cost-effectively, as well as promote knowledge and experience exchange. Retirees can be hired or rehired efficiently. And when they are deployed in customer-facing roles and reflect the customer demographics, they can engage customers effectively. So the business case serves retirees (who want to keep their hands in), the organization (that can hire and onboard people efficiently), and often the customers (who can better relate to the employees serving them).

- Retiree Networks are communities of retirees that can serve as a channel for a variety of activities, including rehiring retirees, collecting business and employee referrals, enlisting retirees to participate in community programs, and, depending on the business, serving retirees as customers. Retiree networks may be organized and managed by the company or the retirees themselves, and they are typically supported by a website, regular communications, and local events.

- Career Reinvention programs serve employees of all ages by facilitating in-company role, location, or career changes. But these “second acts” can be especially valuable for rejuvenating and reengaging older employees, many of whom may not be getting all the career development opportunities that younger colleagues have. Reinventors gain new skills and experience while sharing what they already know. The company can use career reinvention to fill talent gaps, expand skills and experience, and enable mobility and cross-pollination across departments or lines of business.

- Knowledge Exchange happens through a variety of means – from ongoing mentoring, to occasional events, to intergenerational team structures, to online repositories of information. The objectives are both to capture and retain knowledge and experience before it walks out the retirement door, and to accelerate the development and productivity of other employees. Many retirees and pre-retirees are happy to give back to their employers by playing teaching and mentoring roles.

These five programs can work together and reinforce each other, and a comprehensive approach to an older workforce will incorporate several. Programs must recognize what working retirees want – starting with engaging work, enjoyable workplaces, and flexible work arrangements. They must also manage an ongoing tension. On one hand, though typically part-time, retirees want to fit in and be treated like regular employees, including when it comes to learning opportunities and on-the-job variety. On the other hand, they need adjustments appropriate to their lifestage, including to scheduling and compensation and benefits. The special ingredient in many successful programs is how organizations mix the generations, enabling knowledge and experience exchange in both directions. Everyone enjoys that process.

Notes

- 1. Nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, 19th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey, 2019.

- 2. OECD, Labor Force Participation Rate, 2018.

- 3. Zarla Gorvett, “How elders can reinvigorate the workforce,” BBC Generation Project, November 14, 2019; Richard Eisenberg, “How These 3 Countries Embrace Older Workers,” Next Avenue, May 10, 2018.

- 4. Julian Birkinshaw et al., “Older and Wiser? How Management Style Varies With Age,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Summer 2019.

- 5. Unless otherwise cited, all survey results in this chapter are from Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations, 2014.

- 6. Nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, 18th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey, 2018.

- 7. TD Ameritrade, Unretirement Survey, 2019; Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Work in Retirement.

- 8. Diana Kachan et al., “Health Status of Older US Workers and Nonworkers, National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2011,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015.

- 9. Jeff Haden, “A Study of 2.7 Million Startups Found the Ideal Age to Start a Business (and It's Much Older Than You Think),” Inc.com, July 16, 2018.

- 10. Chris Farrell, “Coming Soon: 2 New Encore Career Programs at Colleges,” Next Avenue, March 22, 2018.

- 11. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014.

- 12. Transamerica, 19th Annual.

- 13. Ibid.