9

Funding Longevity: Retirement Is the Biggest Purchase of a Lifetime – That Many Can't Afford

PEOPLE SAVE FOR RETIREMENT gradually, but if you think of the ultimate price tag, it's the biggest purchase of a lifetime. Retirement costs far more than all of life's other big-ticket items – buying a home, raising a child, paying for college. The average “cost” of retirement is over $1,000,000 (Figure 9.1). The cost keeps going up, not only with inflation, but also with longevity. As people spend more years in retirement, they'll need a lot more funds.

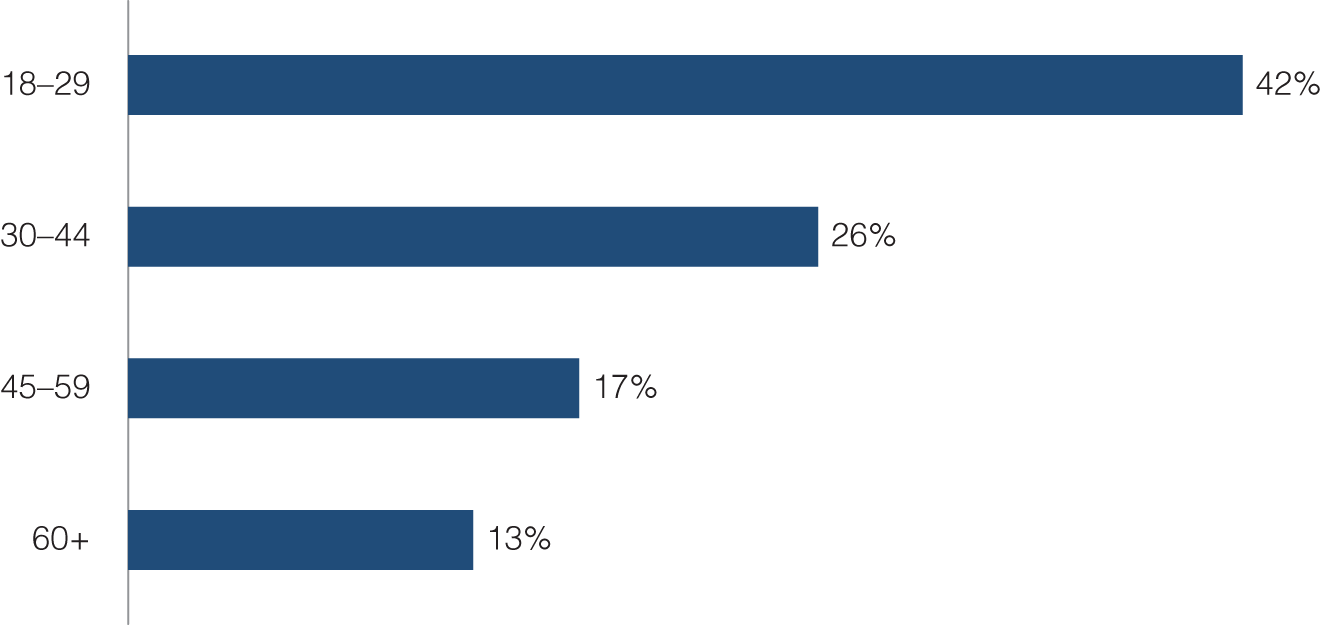

Most Americans are unaware of that price tag. A truly alarming eight in ten have reported that they have no idea how much money they'll need for a comfortable retirement. But they are beginning to realize that they are underprepared – in many cases by a great deal. Only 45% of Americans over the age of 60 feel their retirement savings are on track (Figure 9.2). In fact, the average 60-year-old pre-retiree has saved only about $135,000 toward their retirement.1

How far behind are Americans in funding their retirements? The answer depends on whom you ask and how it's measured. Using the rule of thumb that retirees need 75% of their pre-retirement annual income, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College estimates that half of all working households are at risk of being unable to maintain their standard of living in retirement based on their current savings and retirement income sources. Half of the households age 65+ are in the same situation.2 And half of all Boomers feel they need to catch up on retirement savings. They say they have fallen behind because of inadequate income, unexpectedly having to support family members, out-of-pocket health care costs, and having started saving for retirement far too late.3

Figure 9.1 Retirement Is the Purchase of a Lifetime

Sources: NCES 4 Year Institution, 2016–2017; USDA, 2017; Zillow, 2017; Retirement cost calculated from Consumer Expenditure Survey, National Center for Health Statistics, Social Security Administration

Figure 9.2 Retirement Savings Perceived to Be on Track

Source: Federal Reserve, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Householdsin 2018

Another rule of thumb says that total retirement savings should be at least eight times pre-retirement income. For the average household, that's almost a half-million dollars. That $135,000 average falls far short. And a significant number of households have no retirement savings at all, including 13% of those age 60+ and not yet retired (Figure 9.3).

This is a very serious problem. Are we heading to a new era of mass elder poverty, not seen since the 1930s, when one-third of older people were impoverished? Will the wealthiest generation ever also have unprecedented rates of retirees struggling to stay afloat financially? If nothing major changes, that may well become the case. As income inequality carries over into retirement funding inequality, there will in all likelihood be a public outcry.

The Funding Formula Is Changing: No More Three-Legged Stool

For the second half of the twentieth century, and thus for the Boomers' grandparents and parents, the retirement funding formula was for most a reliable and predictable three-legged stool: (1) personal savings and retirement accounts, (2) guaranteed employer pensions, and (3) Social Security. But the mix and certainty of those three components have shifted dramatically, and it appears that most people haven't made the necessary adjustments.

Figure 9.3 Non-retirees with No Retirement Savings

Source: Federal Reserve, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Householdsin 2018

Living for Today and Not Saving for Tomorrow

In our studies, Americans have told us they think they should be saving 15–20% of their income annually, and they know they should max out all tax-protected accounts such as 401(k)s. But that's not what's happening. The average annual savings rate (all savings, not just toward retirement) in the United States has risen a bit since the recession – largely due to the Millennial generation's savings activity – but is still only around 7%.

While roughly two-thirds of private-sector workers in the United States have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, only 13% of participants contribute the maximum amount allowed (currently $19,500). Incredibly, 26% of those eligible for plans do not contribute to them at all.4 These accounts also suffer what is weirdly called “leakage,” when people tap into them (and bear the tax and penalty consequences), before reaching age 59½. Three in ten have taken a loan or early withdrawal,5 the latter common when people change jobs and fail to roll over their funds. The first leg of the stool is wobbly.

Guaranteed Pensions: Now You See Them, Now You Don't

At the same time, because most private-sector employers phased out guaranteed, or “defined benefit,” pensions in favor of 401(k) and other forms of “defined contribution” accounts, the large majority of today's workers will not have employer-provided post-retirement income for life as their parents might have (Figure 9.4). Just 20 years ago, over half of Fortune 500 companies (59%) still had defined benefit pensions. Today it is only 16%.6 There goes the second leg of the stool.

Social Insecurity

Social Security income can be significant but not sufficient. The average monthly payment is around $1,500. If each party in a couple receives that amount, that's $36,000 a year. Although today's older retirees rely heavily on Social Security, without much-needed adjustments in the program, the long-term viability of those benefits is in question for future retirees. That's because the demographics, including the worker-to-recipient ratio, and the economics of Social Security have changed dramatically since the early days of the program (Table 9.1). Two-thirds of working Boomers now say they're anxious about the availability of Social Security when they are ready to retire. Gen Xers and Millennials are even more concerned, with eight in ten worrying that it won't be there for them.7 They understand that they're nevertheless forced to contribute to Social Security to support their parents' massive generation – the Boomers. That realization is no doubt partly fueling the #OKBoomer outcry.

Figure 9.4 Shifts in Pension Plans

Source: Willis Towers Watson, Retirement Offerings in the Fortune 500: A Retrospective, 2018

Table 9.1 The Changing Social Security Equation

Source: Social Security Administration, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, U.S. Census Bureau, Congressional Budget Office, 2016

| 1940 | 2016 | |

| Life expectancy at birth | 63.6 | 78.8 |

| Additional life expectancy at age 65 | 12.7 | 19.4 |

| Average retirement age | 70 | 64 |

| Population age 65+ (million) | 9.0 | 49.2 |

| Ratio: workers to recipients | 40 to 1 | 2.8 to 1 |

| Number of Social Security recipients | 222,488 | 60,907,000 |

| Average annual Social Security payout | $220 | $16,320 |

| Total Social Security payout (million) | $49 | $916,000 |

| % Federal budget for Social Security | 0.03% | 24% |

As a result, the third leg of the stool is uncertain, and the financial security and peace of mind it was designed to provide is dwindling. So we're back to the first leg. Funding relies more than ever on personal retirement accounts and savings, and there's much more responsibility on the individual to fund one's potentially lengthy retirement.

Retirement Funding Variations Around the World

On average around the world, people now expect the government to provide almost half of their retirement income, their own savings to provide about a third, and employer pensions to cover one-fourth.8 However, funding practices vary greatly. The Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index rates retirement systems using more than 40 indicators grouped in three sub-indices: adequacy of support, sustainability of the system, and integrity of oversight. The top scores (As on an A to E scale) in 2019 went to Denmark and Netherlands. The United States received an unimpressive C for adequacy and C+ for sustainability and integrity.

Other countries have very different retirement funding mixes. In Belgium, about 85% of funding comes from public transfers. In nearby Netherlands, it's under 50% and a large share of the rest comes from occupational, or industry-wide, pensions. Canadians rely most heavily on private pensions and individual savings and retirement accounts. The pension rate, or coverage of pensions compared to working wages, also varies dramatically. Pensioners in the Netherlands receive on average slightly more than what their wages were while working. In the U.K., the pension rate is only 29%. The EU average rate is 71%, in China 83%, in the United States only 49%.9

A sample of the United States, Australia, and six European countries found that most workers were saving less than 10% of their income toward retirement. But again practices vary. The Netherlands requires contributions of the equivalent of 20–25% of people's salaries, the bulk of it by the employers.10

Widespread Lack of Understanding, Confidence, and Trusted Advice

Most people, even those in their fifties who should be focused on funding their retirements, don't understand the often-complicated language and mechanisms of finance. Two-thirds of Americans age 50+ say they find financial industry language unfriendly and not at all understandable. So their “financial IQ” isn't high. Only 60% say they clearly understand the popular terms “IRA” and “401(k).” (And who named it 401(k)? Talk about user-unfriendly – it sounds like the name of a star system at the fringe of the Milky Way.) Even fewer understand the problem of account “leakage” or the process of asset “decumulation” in retirement. A mere 17% grade themselves high on understanding how Social Security works.

That's unconscionable. How can a government put people in charge of saving for their longevity and not educate them about how to do it? Nearly two-thirds of retirees say they wish they had been more knowledgeable about retirement saving and investing during their working years.11 Only 46% say they're doing a good job at drawing income from their savings and investments in retirement.12

To compound these problems, most retirees don't discuss financial matters as much as they probably should. That's in part because, in the minds of many, discussing finances is still socially taboo. Americans are near unanimous (92%) in saying that personal finances are a private matter, and nearly half of retirees say they don't discuss retirement savings, investments, or finances even with close family or friends.13 Many people are more comfortable talking about their end of life than about their finances.

Michelle Seitz, Chairman and CEO of Russell Investments, says, “The industry has an obligation to redesign itself to more effectively provide for people's financial security.” In a 2019 memo she wrote: “We have an escalating societal crisis…. Today's worldwide retirement savings gap has surpassed $70 trillion. According to the World Economic Forum, that number is expected to reach $400 trillion by 2050.”14

At the individual level, Seitz points out that given the magnitude of the shortfall, people deserve to understand their options. It needs to be their choice to work longer, reduce spending, leverage financial tools like reverse mortgages and annuities, or plan to rely more on family and friends. But her main message is a challenge: “Our industry's silence only serves to magnify the problem. As an industry, let's admit that none of us have a panacea product that completely solves this…. What can make a significant difference are savings levels and contribution rates. If a worker is significantly underfunded … they will either need to save more or their employers will need to contribute more, or both.”

Retirees have told us repeatedly that they don't know who or what is a reliable source of advice on managing their assets for and in retirement. Less than 40% work with financial advisors. More than 40% say they have no dependable sources of advice at all.15 And what sources do they trust? Most trusted are financial professionals, family, and friends. Least trusted are social media, the internet, and news media generally. In between are employers, financial institutions, and the financial news media.

More than a third of American adults (36%) say that financial decisions are the ones they second-guess the most (in second place at 18% is decisions about job and career). People may lack confidence in their financial decisions, yet they want to project financial confidence in front of family and friends. Sixty percent agree that, “It's important that others think I'm in control of my finances.”

Digital Advice and Support on the Rise

Older Americans are not yet the heavy users, but financial services are becoming increasingly digitized and democratized. Enormous amounts of information and plenty of financial management tools and calculators are available online. Robo-advisors and hybrid robo-plus-human financial advising services are common. The number of options can be confusing, but retirees who want to learn and do more about managing their finances have resources at their disposal. And there's market opportunity for financial services firms that simplify and package services to meet retirees' needs. As Bessemer Venture Partners points out, today's proliferation of “fintech” products and services are aimed primarily at young “digital native” consumers, not at the older ones who have wealth, spend differently, and need different services and solutions. Technology platforms addressing their needs have appeared but we expect that will continue to evolve in the years ahead.16

David Tyrie, who heads Advanced Solutions and Digital Banking at Bank of America, shared his perspective on digital strategy: “Our digital platforms strive to bring never-before-possible convenience and personalization to our customers. For example, our virtual assistant, Erica, can proactively detect if there are duplicate charges on your account or notify you if your spending is higher than usual. While Gen Zs and Millennials are quick adopters of our digital platforms, we see adoption at every age and we believe our digital tools can make everyday banking experiences simpler and more convenient for everyone. Digital, however, is only half of our ‘high-tech, high-touch’ approach that relies on the expertise of our people and the relationships they build with customers.”

Holistic Preparation for Retirement

It's hard to turn on the news in the evening without seeing ads from financial services firms offering to help you plan for your retirement. Most of the major ones have lines of business that help customers understand their financial situations, sort through their options, and manage their money and savings both in preparation for and during retirement. They all strive to advise and support customers in more comprehensive and holistic ways (and we hope this book helps the cause). Here's what a few of the executives we have spoken with and followed have to say about the industry's objectives and challenges today.

Andy Sieg, President of Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, recounts the recent evolution of financial planning: “For people to experience and achieve what matters to them in retirement, they need good financial planning in dollars-and-cents terms, but it has to be in the context of their plans for life. In this new environment, it's not just about money. Good advisors are trained in assimilating many perspectives. They go through a systematic process to identify what matters to retirees in non-financial terms. To help them do an inventory of their personal values and objectives, as well as their financial objectives and tolerance for risk. Advising has grown more complicated over time because it's not just build a 60/40 investment portfolio, let it run, and hope for the best. It's an equation with many more dimensions that we're trying to solve.”

His colleague David Tyrie adds: “We know that, whether big or small, financial decisions are about more than money; they are about living a better life. That is especially true during retirement, where financial wellness can have a major impact on one's overall experience. After all, for many of our clients, retirement will be the most significant expense they face during their lifetime. Financial advisors should help them navigate the retirement journey, whether it's projecting savings needs, building an investment strategy, helping them decide when to retire, or taking steps to downsize their home.”

Ken Cella, who leads the Client Strategies Group for Edward Jones, told us, “Our clients' needs are complex and their expectations have never been higher. Given that complexity, they are looking to us to provide holistic solutions. Financial advisors are required to have the EQ and IQ – the emotional intelligence and empathy to understand the client's perspective, standing in their shoes to anticipate what they have not yet articulated.”

Challenges Women Face

Women have greater need than men for financial planning both before and during retirement, for a variety of reasons. First, they are paid less than men – 82% for the same work. Over a lifetime, that adds up to a $400,000+ differential. Second, women have longer retirements, retiring on average two years earlier and then living an average five years longer than men.17 Third, women tend to have less saved for retirement after spending more time out of the workforce as parents and then as caregivers.18 The average American woman has a 401(k) balance that is only 68% of the average man's.19 Fourth, given their longevity, women are more likely to need long-term care services. As couples grow older, the husband more often suffers health problems before the wife. She cares for him, sometimes for years, often depleting her energy and their finances along the way. Then when he dies, who will care for her? Women account for 61% of home health clients, 66% of nursing homes residents, and 71% of residential care community residents.20

Award-winning financial planner Ric Edelman says, “Longer lives, lower pay, less savings, more giving and receiving care – that combination makes financial planning really a women's issue. Women must engage in financial planning and management, and financial services firms must engage them. And to men who have traditionally been in the financial lead, I say encourage the women in your lives – mother, wife, sister, daughter – to get the financial planning support they need.”

Women's pay gap while working carries over as a pension gap in retirement. Across the OECD, the average gender difference in pensions is more than 25%. In Denmark, it's only 10%, versus 40% in the U.K. and Netherlands. The pension gap in the United States is about one-third, in Japan almost one-half. If we add the pay gap, the effect of work interruptions, and the pension gap together, the “wealth gap” for an American woman in retirement can be over $1.2 million (Figure 9.5).

However, we're also seeing more financial independence among women retirees. They are coming into their own financially, thanks largely to how Boomer women differ from previous generations. They are twice as likely to have college degrees, more than half again as likely to have been working in their twenties, and twice as likely to be divorced, separated, or never married. They have more experience and confidence as investors, and more awareness of the challenges they face funding their retirement.

Figure 9.5 Women's Lifetime Cumulative Wealth Gap

Source: Age Wave calculation21

Course Corrections in Retirement

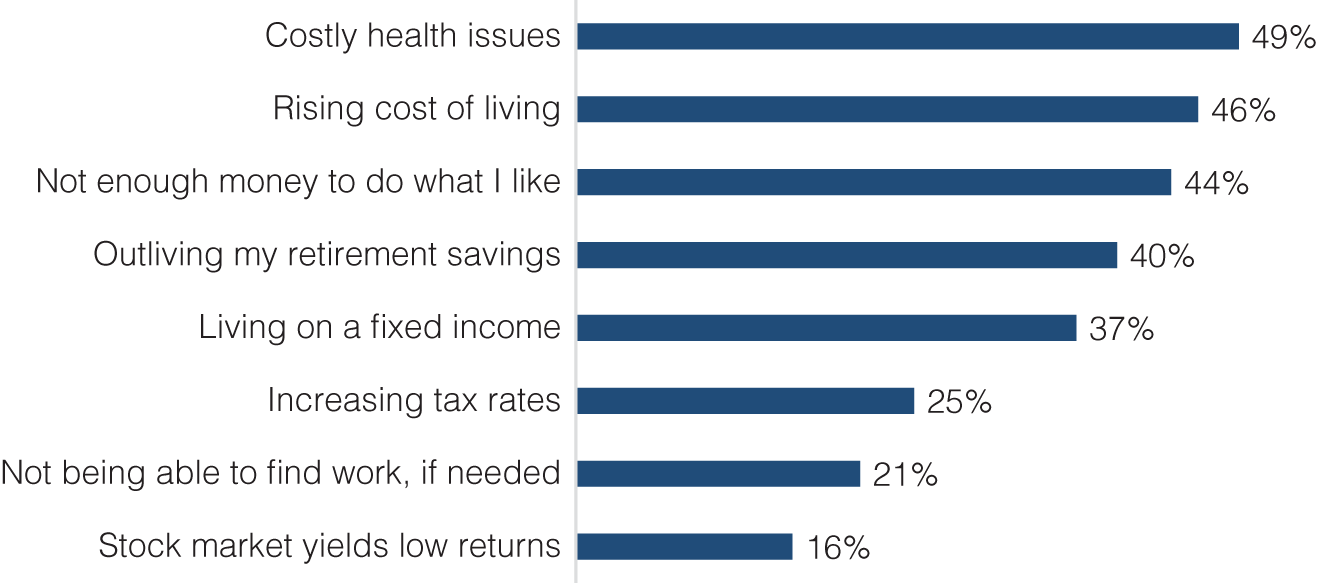

Well prepared or not, people retire and adjust to living on a new mix of spending habits and income sources. But most have three things in common. First, they worry about finances, starting with the potential expense of health problems (Figure 9.6). Other commonly cited concerns are rising costs, lack of money to do the things they want to do, and outliving their wealth.

Second, their objective is peace of mind, not wealth in itself. Given the choice, 88% say that they would like to save enough to have financial peace of mind, only 12% that they would like to accumulate as much wealth as possible. What constitutes financial peace of mind? For the majority (57%), it's simply being able to live comfortably within one's means. For many, it includes freedom to enjoy one's lifestyle, or confidence that unexpected expenses can be handled. What can disrupt financial peace of mind? Most commonly cited are health disruptions (87%), large unexpected expenses (84%), and loved ones needing financial support (57%).

Figure 9.6 Financial Worries in Retirement

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Finances in Retirement: New Challenges, New Solutions

Third, retirees are resilient and adaptable, willing to make lifestyle adjustments and course corrections (the less painful the better) during retirement in order to maintain their financial footing and enjoy this new stage of their lives. The most basic involve adjusting finances, working more, and spending less.

Adjusting Financial Structures

Some course corrections are directly financial. These include maximizing the tax benefits of retirement accounts, finding other ways to reduce taxes, and adjusting the timing (either accelerating or postponing) of initiating Social Security benefits. A strong majority of retirees (60% or more) would consider each of those actions. They are less willing (43%) to withdraw cash value from life insurance policies. One in four would consider declaring bankruptcy as a financial expedient.

Bankruptcy filings are “graying” with the population. The bankruptcy rate for age 65+ households has tripled over the last three decades.22 Individuals age 65+ now account for over 12% of all bankruptcy filers, a dramatic rise from 2.1% in 1992.23 Bankruptcy is a way to discharge medical and credit card debt while homestead exemptions can protect the primary home and savings in retirement plans are protected by law. Older household average debt (excluding mortgage) has declined to pre-recession levels, but at roughly $33,000 it is four times the 1991 level.24 A growing source of debt is student loans taken out on behalf of children and grandchildren.25

Meanwhile, some retirees and pre-retirees hope for or expect inheritances to add to their retirement funds. Thirty-seven percent of Americans age 50+ have received an inheritance from a family member or someone else, and another 7% say they expect to.26 A lot of money is in motion. Nearly two million inheritances are received each year, amounting for nearly $300 billion in transferred wealth. More than half of inheritances received are $50,000 or less, while only 2% are $1 million or more.27 The likelihood of an inheritance peaks at around age 60, when parents are in their 80s. Not surprisingly, people in the top 10% of income distribution are twice as likely to receive an inheritance as those in the bottom half of the distribution.28

Working More

How do people try to catch up financially? The greatest impact comes from working a bit longer, even part time. That adds time to save and delays tapping into retirement savings. While working, people can maximize their contributions to 401(k) and other IRA accounts, and 60% of pre-retirees said they would delay their retirement to improve their finances.

As we detailed in Chapter 4, working part time in retirement is becoming the new normal. Seven in ten Boomers expect to work past age 65, are already doing so, or do not plan to retire at all.29 Many retirees work out of financial necessity, but the majority work for a combination of both personal and financial advantage – staying active and socially engaged while supplementing their retirement income. Andy Sieg sees an increasingly important role for work: “Many retirees' income streams from savings and Social Security are insufficient. However, we've been very fortunate that, at the same time as the longevity wave has been building, the nature of work and the workplace have changed in ways that make it much more feasible and energizing and socially rewarding for people to continue working later into life. Retirees want to stay active and engaged, especially mentally, and the twenty-first century multigenerational workforce values skills and experience. So I'm optimistic about the overall Boomer financial journey through retirement because of the extent to which they're staying active and engaged and working.”

Today's retirees are already working in a variety of formats – regular part time or seasonally, in their former occupations or trying something new, for their old employers or working for themselves, monetizing a hobby or starting a new business. The gig economy offers work-when-you-like options, from driving for rideshare services, to doing administrative or technical piecework online at home, to teaching English to children in China for VIPKids. If needed to improve their finances, three-fourths of retirees and pre-retirees say they would return to work part time in retirement, and 43% would consider working full time.

Spending Less

Cutting back on expenses is an obvious course correction. Nine in ten retirees say they'd do so if needed, and 60% say they spend less money now than when they originally retired.30 Retirees have more time to do their homework and manage their budgets. Finding discounts and taking advantage of loyalty programs help the cause. But retirees want to maintain and enjoy their lifestyles, so general belt-tightening can definitely have a positive effect.

For some, thoughtful cost-cutting is the essence of a retirement plan. Edd and Cynthia Staton were undone by the economic crisis – careers, investments, home equity. Seeing no way to catch up, in 2010 they moved to Cuenca, Ecuador, where they could afford to live on the money they had. They write and blog about their experience and help others researching retiring abroad at their website eddandcynthia.com. Their bottom line: “Turns out it was one of the best decisions we've ever made…. Those financial nightmares are a thing of the past.”

Another approach is extreme downsizing. Luxtiny is a tiny-house community in Lakeside, AZ. Custom-built or standard models range from 162 to 399 square feet. Options include a storage shed and a 144-square-foot guest house, and houses can be built in the community or anyplace in the state. Standard models start at $59,000, and custom houses can cost over $100,000. Owners save significant money across the board – purchase price, insurance, utilities, maintenance. Visitors are amazed on how much by way of both functionality and possessions can fit into a comparatively very small space.31

Some Additional Course Corrections

The retirees we surveyed indicated their willingness to make a variety of other course corrections with financial impact. For example, they say they'd sell possessions, perhaps the second car if no longer needed, perhaps as part of a decluttering process. Another way to make money is by turning a hobby into a source of income. Next Avenue has profiled a variety of retirees who make money and enjoy themselves by monetizing their hobbies. And it's not all woodworking, knitting, and other crafts. Examples include a contract bridge instructor, a purveyor of home-recipe gourmet nuts, and a travel-loving couple who hire out as fill-in innkeepers.32

Finally, one of the most beneficial actions retirees can take is investing in their health – exercise more, eat better, or stop smoking. The payback can't be precisely calculated, but better health means lower everyday medical expenses and the delay or better management of chronic conditions and their long-term costs. The value in terms of personal well-being can be felt even sooner than the financial value.

With all these potential course corrections, retirees need guidance assessing what moves will really make a difference for them. Expense-cutting may be straightforward, but major financial course corrections can be complicated. Some involve decisions, such as selling a house or purchasing an annuity, with long-term implications. Tapping the cash value of life insurance policies can sometimes be beneficial if the original need for the insurance has declined. Just deciding when to initiate Social Security benefits – early, at “full retirement age,” or as late as possible – is puzzling for most Americans. Eight in ten retirees say they are willing to seek professional financial advice on these matters; however, as we mentioned, only about half as many actually work with advisors.

Spending and Decumulating in Retirement

The guideline we mentioned that retirees need 75% of their pre-retirement annual income seems a reasonable approximation in light of research from J.P. Morgan. However, spending doesn't always drop by exactly one-fourth upon retirement. The long-term pattern has household spending peaking when people are in their 50s, then gradually declining until leveling off around age 80. After age 60, the only cost category that increases is, as we would expect, health care. The short-term pattern has spending increasing measurably but not dramatically (about 5% on average) in the year before retirement. People may be investing in pre-retirement adjustments like home renovations or splurging on that retirement celebration trip. A year into retirement, spending is back to where it was a year before retirement.33

This analysis has good news for retirees. They may need less money in retirement than the retirement funding calculators typically suggest. But there's some bad news as well. They may be tapping into more of their retirement funds earlier than planned at the start of retirement. We can also conclude that a few years before retirement is a difficult time to still be playing catch-up financially.

Another common guideline is the 4% rule for drawing down, or “decumulating,” retirement savings. Taking 4% of the total nest egg per year, adjusting for inflation (so the withdrawal amount grows a bit each year), can cover a 30-year retirement. The simple math works, but there are major variables, including the size of the initial nest egg, performance of investments, and the age when decumulation starts. An annual 4% withdrawal may do little to supplement Social Security and any pension income, and little to support the retiree's preferred lifestyle. In that case, adjustments are needed to income and outlay.

One of the biggest variables behind how much retirement costs and the pace at which retirees spend is location. GOBankingRates calculated how long a $1 million nest egg lasts on average state-by-state across America. It would last 25 years or more in Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Michigan, or Tennessee, but only around 17 years in California, Alaska, New York, Connecticut, Maryland, or Massachusetts. In Hawaii, it would be consumed in a dozen years.

Guaranteed Paycheck for Life? The Potential Role of Annuities

Financial annuities got a major shot of awareness when the Alliance for Lifetime Income, the industry association of annuity providers, was the sole sponsor of the Rolling Stones recent North American tour. Annuities are insurance products that turn an initial lump sum premium into lifetime income, like a regular paycheck. They are typically purchased with proceeds from a 401(k), IRA, or other retirement savings account. An annuity provides income for life, thus serves as a form of “longevity insurance,” with a minimum payment period's value guaranteed to the estate if the insured dies early in the annuity contract.

When asked to describe the ideal retirement investment, three-fourths of American adults said something that provides guaranteed income and something that is guaranteed not to lose value.34 That's an annuity. However, annuities come in complicated variations, many consumers are wary of them, and they are underutilized. Todd Giesing of the LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute feels that the market is poised to grow: “The overall annuity market will thrive in an aging population. The number of people reaching age 65 or older will reach 60 million by 2023 – the target market for individual annuity products.”35 Abaris serves as a direct-to-consumer marketplace for retirement annuities from insurers such as AIG, Pacific Life, Guardian, Principal Financial Group, and Lincoln Financial Group.

The primary upside of an annuity is the security of guaranteed income. An insured person who lives long “comes out ahead.” And for people who lack financial discipline, annuities prevent them from spending down their assets too fast. The downsides start with the money's no longer being in the insured's control – it takes a psychological leap to trade a lump sum for a series of payments in return. Inflation can reduce the spending power of payments (though cost-of-living riders are available). The insurance company could fail (though contracts are government-backed up to a limit). And if the insured dies prematurely, the estate can “come out behind.”

Andy Sieg takes a measured view of annuities: “It's hard for the private sector to create a broad annuity market, from Boomers to Millennials, because what company wants to bet against longevity? There could be a breakthrough in genetic engineering that dramatically increases life expectancy, and that makes it challenging to be out there with an open-ended guarantee of lifetime income. For a program to scale in a big way, it would have to build on the bones of Social Security or reinvent Social Security for a new century.”

Many financial experts recommend annuities or other guaranteed-return investments as part of the retirement funding mix. The idea is to establish a combination of annuity, pension, and Social Security income to meet retirees' baseline living expenses indefinitely, regardless of the performance of any other investments. If consumers are shy about annuities, that creates opportunities for financial services institutions that can simplify and more effectively explain and market them.

Cash Poor But Brick Rich: Ways to Monetize the Biggest Asset

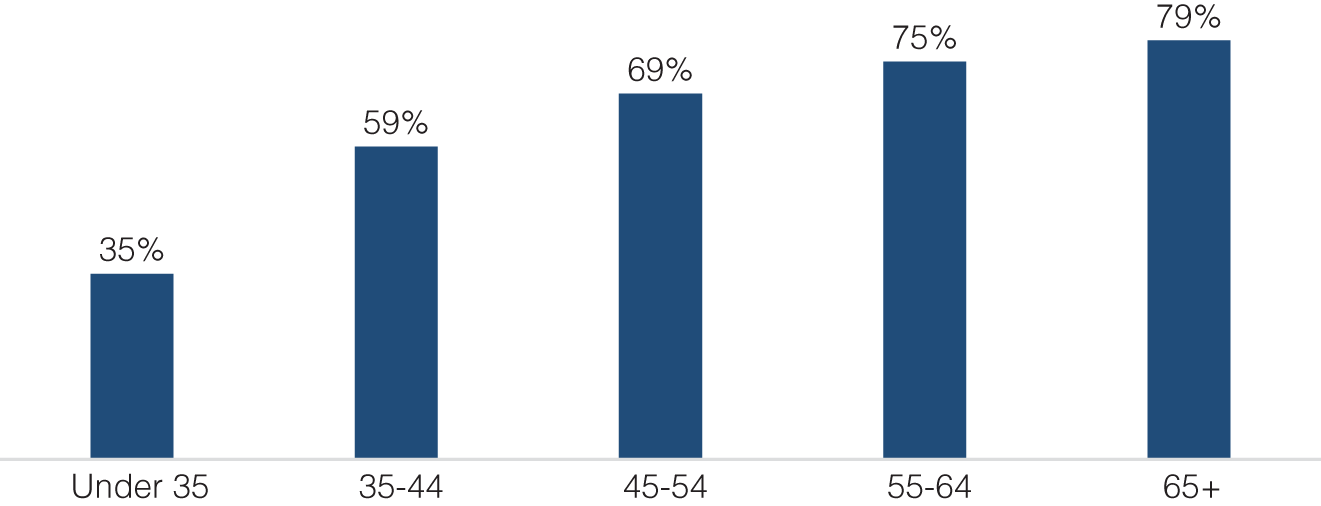

Owning a home remains a solid part of the American Dream for 90% of adults of all ages.36 But it takes time for most of us to accumulate a down payment and establish the cash flow to service a mortgage, then 20 or 30 years to pay it off. So homeownership and home equity naturally skew older. A majority of Americans have become homeowners by age 40. Among those age 65 and older, 79% own their homes (Figure 9.7), and seven in ten of those have paid off the mortgage. Their home equity, averaging nearly $300,000, may represent a significant portion of their total net worth, not to mention a big contributor to their financial peace of mind. The total home equity held by age 62+ American households reached a record $7.14 trillion in 2019.37

In the years ahead, one of the most significant financial moves in retirement for many people may be to monetize the value of an owned home. Sell and then rent, adding all the proceeds to the retirement fund. Or sell and buy a downsized home, pocketing the difference. And perhaps relocate in the process to someplace with lower housing, living, and property tax costs. For example, suppose a 62-year-old New Jersey couple sells their $325,000 house that still carries a $75,000 mortgage. They buy a $135,000 house in South Carolina, freeing up $115,000 to invest or spend, and leaving them mortgage-free. Over the next 15 years, their savings in cost of ownership (mainly lower property taxes) and cost of living average $28,000 per year, or an aggregate of $420,000. If both live to age 90, the aggregate saving is $620,000.

Figure 9.7 Homeowners by Age

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2017

Retirees we surveyed tell us that, though emotionally attached to their homes, they are willing to adjust. Three in four would downsize. Two-thirds would relocate to someplace less expensive or cut back on home improvements and repairs. Nearly half would consider selling and then renting.38 And renting seems to have growing appeal. The number of age 65+ households that rent is projected to increase by a whopping 80% from 2015 to 2035.39

Especially if home equity is going to be a significant source of funding in retirement, most retirees need help considering all the variables – mortgage or rent payments, property taxes, insurance, utilities, and maintenance and repairs. They need help considering all the options – including stay-put alternatives such as home equity loans, reverse mortgages, and refinancing when rates drop. And then help determining what home equity actions make the most sense.

Selling or borrowing against it isn't the only way to monetize one's house. Older Americans have become the fastest growing segment as both hosts and patrons of Airbnb. In 2017, hosts over age 60 earned $2 billion from Airbnb by accommodating 13.5 million guests across more than 150 countries. Airbnb embraces the retiree market: “Airbnb is helping to redefine retirement by providing new ways to earn extra income, overcome loneliness and isolation, and travel the world in a truly local and authentic way.”40

A Role for Reverse Mortgages?

Many retiree homeowners are cash poor and brick rich, thus potentially interested in ways to tap into their equity. Home equity loans, home equity lines of credit, and reverse mortgages are all forms of “home equity release,” whereby homeowners can get cash while retaining the right to live in the home.

With reverse mortgages, the homeowner receives monthly income based on the home's value, no payments are made, and the balance (along with interest) is repaid when the borrower (or last borrower) sells the property, moves into permanent long-term care, or passes away. If the loan balance then exceeds the value of the property, the borrower or borrower's estate is usually not required to pay the difference.

Reverse mortgages are marketed as ways to supplement retirement income while having the security of owning a home. Retirees commonly use the money to cover everyday expenses, make home improvements, pay off other debt, or take trips and enjoy their leisure. Older homeowners have traditionally treated the mortgages as a last resort, but attitudes may be changing as both retirees and their heirs are focusing less on inheritances being passed down and more on enabling retirees to live comfortably.

Equity release has gained some popularity in the U.K., where retiree homeownership is high, and the market is approaching £4 billion a year. The Equity Release Council finds that nearly a half million homeowners have released equity with the help of their member institutions over the last three decades. Retirees trust the products because the industry is regulated, lenders are conservative regarding loan size, and sales are predominantly through financial advisors.41

In the United States, reverse mortgages are less popular – the market is not much larger than in the U.K. despite almost five times the population. Reverse mortgages are increasingly promoted by television ads featuring celebrity spokespeople, but consumer uncertainty remains high. The products can be complex and difficult to understand. Some retirees take out the mortgages too early, draw down all their home equity, and find themselves in financial trouble paying property taxes and maintenance. When the loans are paid off, borrowers or their heirs can be taken by surprise by the settlement complications and how little equity remains.

Ric Edelman, founder of Edelman Financial Engines and three times ranked the country's top financial advisor by Barron's, says: “In principle, reverse mortgages are a wonderful idea. Unfortunately, current products fail to serve the best interests of most homeowners, so anyone interested in generating income from their home equity should proceed with caution.”

Reverse mortgages could become a useful part of more retirees' financial plans. However, as with the annuities market, we believe it will likely take the combination of simpler and more transparent products and better consumer protections for the market to really take off. Until then, independent advisors can help retiree homeowners make sure the products are clearly aligned with their financial interests.

Coping with Health Care Costs

Health care cost is many retirees' greatest financial worry for good reason – the costs are high, increasing, and uncertain. Most retirees are willing to spend what they can afford to regain or maintain their health. But for those of modest means, sudden and unanticipated health care expenses can be financially disastrous. This concern is ubiquitous, as Andy Sieg points out: “Health care funding is not a niche topic or niche market. When you talk about it, everyone tunes in. Everyone is thinking about longevity and the need for caregiving and the worry about dementia. Look how quickly Alzheimer's became a dominant health concern. More people are trying to balance caregiving to their parents with the needs of their immediate families, and it's something they have to engineer on their own for the first time.”

Longer retirements naturally mean more accumulated out-of-pocket health care costs (Figure 9.8). Even with some recent reforms, medical costs have continued to outpace inflation. Since 2000, they have risen an average of 3.41% per year, half again the 2.12% rate for total consumer categories.42 Adding to the financial challenge is that retirees are largely on their own paying for Medicare supplement programs and other out-of-pocket costs. And like guaranteed pensions, “now you see it, now you don't.” As recently as 1988 two-thirds of large employers provided retiree health care benefits. Today it's only 18%.43

Figure 9.8 Out-of-Pocket Health Care Costs if Your Retirement Lasts …

Source: Dale H. Yamamoto, Health Care Costs – From Birth to Death, Health Care Cost Institute Report, 2013

Fidelity Investments estimates that a 65-year-old couple retiring in 2019 can expect to spend $285,000 out-of-pocket in health care and medical expenses in retirement.44 That's more than the average home equity and more than the median household net worth of Americans 65 and older.45 And that estimate does not include long-term care.

Only 37% of Americans anticipate that they may need long-term care at some point, when informed estimates put it at about double that (70%).46 In 2018 the average annual long-term care costs in the United States were $45,800 for a home health aide for 40 hours/week, and $89,300 for a semi-private nursing home room.47 Total out-of-pocket expenditures were $9.6 billion on home health care and $46.1 billion on nursing home and continuing care facilities. The average lifetime costs for an individual's paid long-term support services is $266,000, more than half of it not covered by insurance and thus out-of-pocket.48 Aggregate national spending on home health care is expected to nearly double in the next 10 years.49

Retirees can protect themselves from the high cost of long-term care. But the market for traditional long-term care insurance hasn't taken off because it's perceived as an expensive “use it or lose it” proposition. That is changing with the availability of hybrid life-and-care insurance. LIMRA reports that sales of annuity/long-term care combinations have surpassed sales of individual long-term care policies for the last five years.

Retirees need help understanding, anticipating, and managing the costs of their health care, balancing the objectives of quality care and financial asset protection. But many don't really understand their health insurance coverage to begin with. Over 40% erroneously think that Medicare will cover nearly all their health care and long-term care costs.50 Part of the problem is that many find information on insurance and costs to be complicated, often overwhelming. Among people age 55–64, only 7% say they feel knowledgeable about Medicare and its options.51 That only rises to 19% of those over 65 who are currently covered. It's perhaps one of the reasons that AARP and UnitedHealthcare's partnership leads the market. Millions of people, unable to figure out the whole crazy world of Medicare Supplements, think, “Well, I can't tell the difference, but if AARP is supporting UnitedHealthcare, it must be good.” They're probably not aware of the more than $600 million that AARP receives each year through the arrangement.

Anticipation and preparation should start well before retirement, yet health care is often a missing link in retirement planning. Only 15% of pre-retirees say they have ever attempted to estimate their health care and long-term care expenses in retirement.52 Nearly all would welcome guidance on Medicare and supplemental plans, long-term care, other insurance and funding options, and how much money they may need for health care. However, as with financial advice generally, few say they have a trusted source for answers on financing health care.53 As we discussed in the chapter on health, they could use something like a personalized “Health Waze” app.

At the point of retirement, most people also need to play catch-up with how they'll fund their health care. A retiree we spoke with shared her sticker shock: “I read the numbers on what health care can cost. I didn't even think about that when saving for retirement.” Another put the challenge bluntly: “Uncertainty is the real problem. If only I had an expiration date, I'd know how much I need to save.”

Avoiding Elder Fraud: A Hidden Menace

Financial fraud and abuse are a scourge on older Americans. True Link Financial estimates the losses at over $36 billion annually across three categories. Exploitation accounts for about $17 billion in losses, as when people use misleading language and pressure tactics to get seniors to pay for things that are marked up, unneeded, or worthless. These include subscriptions, quack products and services, work-from-home schemes, and hidden shipping and other fees. Individual amounts lost may be small, but the number of incidents is uncountable.

The second category, criminal fraud, includes email and phone scams to obtain financial information and money directly. Nearly $10 billion is lost to scams, $3 billion to identity theft. And the third category is caregiver abuse, where $6.7 billion is lost, mainly through theft, to trusted people – family members, paid helpers, friends, lawyers, or financial managers.

The National Adult Protective Services Association describes the common ways family members and other trusted people exploit vulnerable adults. Direct financial abuse often involves misuse of powers of attorney, withdrawing funds from joint bank accounts, or using the victim's ATM card or checks to take funds. In-home care-givers may overcharge for services or simply not perform them, or “keep the change” from errands. Family members may not arrange for medical care the recipient needs in order to keep the money available to themselves. And financial abusers may resort to threats to abandon or harm the victim if they don't get their way.

Financial institutions are increasingly vigilant, and the number of “elder finance exploitation” (EFE) “suspicious activity report” (SAR) filings is rising steadily. But it's estimated that the 63,500 SARs in 2017 may represent less than 2% of actual incidents, and more than 3.5 million older adults were victimized that year. The banks tend to report the larger losses. The slight majority of SARs are associated with strangers, and the median loss is $8,500. Those associated with persons known to the victim have a median loss of $23,300. The likelihood of incidents increases with age, and the highest average losses are incurred by people in their seventies.

Preventing financial fraud and abuse also requires vigilance by individual retirees, with some technological help. For instance, EverSafe is a subscription service that monitors activity and patterns of bank, credit card, and investment accounts and issues suspicious activity alerts and warnings about unusual withdrawals, missing deposits, and unpaid bills. EverSafe was created by Howard Tischler after his aging mother received an unusually high credit card bill with fraudulent charges including an auto club membership. His mother was legally blind and didn't own a car. Tischler says, “Baby boomers control trillions of dollars in wealth, much of it in retirement funds. And as that big generation gets older, a treasury of life savings will increasingly beckon predators who are cunning with computers.”54

Tools and Resources to Help Keep Affairs in Order

There's one more financial matter to attend to in retirement – keeping one's formal “affairs in order.” Retirees care very much about the legacies they leave. They want to remain in control in their final years, including in control of their late-in-life health care. And they want to enrich rather than burden the lives of their loved ones and heirs.

So they need three essentials: a will or trust to control distribution of assets not already covered by beneficiary arrangements, a durable power of attorney to make financial decisions if one is incapacitated, and health directives specifying treatment preferences and who can make medical decisions if one is incapacitated. In addition, their key documents (including insurance policies, real estate titles, family medical history, and account passwords) need to be organized and secure but accessible.

Unfortunately, the overwhelming majority of older Americans cannot claim to have their affairs in order. Only 55% of those age 55+ have a will, and only 18% have the trifecta of a will, power of attorney, and health directive (Figure 9.9). One-fourth of those age 75+ still lack a will,55 and an estimated 23% of wills in force are out of date.56 Best prepared are widows, who have learned from the experience of dealing with their deceased spouses' end-of-life and legacy matters.

Figure 9.9 Possession of the Essentials among Ages 55+

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Leaving a Legacy: A Lasting Gift to Loved Ones

What does this mean for the unprepared and their families? The unprepared are increasing the odds that they will be financial and caregiving burdens on their families. And they risk diminishing their personal legacies, because heirs recognize that dying without having the formal affairs in order is irresponsible. The heirs inherit disarray and headaches as part of the estate.

Some of these preparations begin early in life – executing a will upon marriage or buying life insurance upon becoming a parent. However, a concerted effort to get one's affairs in order is usually triggered later in life by a health scare in the family, a life event like retirement, or the influence of family, friends, doctors, or financial advisors. A lot is already changing at the point of retirement, and that can make it a good time to get some affairs in order, to consider the still-distant as well as the immediate future.

We're seeing online services and tools to help retirees with rudimentary estate planning and organization of their affairs. For example, Future Vault is a “digital safety deposit box” that enables people to share with financial advisers their financial, legal, and personal as well as small business documents. Genivity is a similar service that also incorporates family health information so financial advisers can consult with clients about health risks in conjunction with financial and estate planning. Both tools support clients' relationships with their planners. Whenever assets are significant, family structures are complex, or life and health circumstances are complicated, keeping affairs in order requires the help of financial, legal, and estate planning professionals.

Funding retirement rightly focuses on saving and preparing well in advance. But even if retirees have attained their “magic number” of funds accumulated, other factors – starting with family and health – can disrupt their plans. “Easy Street” is a bit of a myth. Many people need closer attention to – and more help with – their finances during retirement than before.

Notes

- 1. Ann Brenoff, “Here's How Long $1 Million in Retirement Savings Will Last in Your State,” Huffpost, August 25, 2017; Darla Mercado, “Here's the Number 1 reason why seniors work well into retirement,” CNBC, October 9, 2019.

- 2. Anqi Chen, Alicia H. Munnell, and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, “How Much Income Do Retirees Actually Have? Evaluating the Evidence from Five National Datasets,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, 2018.

- 3. TD Ameritrade, 2019 Retirement Pulse Survey.

- 4. U.S. Government Accountability Office, The Nation's Retirement System: A Comprehensive Re-evaluation Is Needed to Better Promote Future Retirement Security, 2017; Vanguard, How America Saves 2019.

- 5. Nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, 19th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey, 2019.

- 6. Brendan McFarland, “Retirement Offerings in the Fortune 500: A Retrospective,” Willis Towers Watson, 2018.

- 7. Transamerica, 19th Annual.

- 8. Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement, The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, 2019.

- 9. OECD, Pensions at a Glance 2017.

- 10. European Commission, “Country Fiche on Pensions for the Netherlands – The 2017 Round of Projections for the Ageing Working Group.”

- 11. Nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, A Precarious Existence: How Today's Retirees Are Financially Faring in Retirement, 2018.

- 12. Society of Actuaries, 2017 Risks and Process of Retirement Survey, 2018.

- 13. Transamerica, A Precarious Existence.

- 14. World Economic Forum, “Investing in (and for) Our Future,” 2019.

- 15. Transamerica, A Precarious Existence.

- 16. Charles Birnbaum and Tali Vogelstein, “Roadmap: Fintech for the aging,” Bessemer Venture Partners, September 27, 2019.

- 17. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Frequently Requested Data, 2018; Centers for Disease Control, National Vital Health Statistics: Life Expectancy, 2016.

- 18. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Women & Financial Wellness: Beyond the Bottom Line, 2017.

- 19. Vanguard, How America Saves 2019.

- 20. CDC National Center for Health Statistics, “Long-Term Care Providers and Service Users in the United States 2015–2016,” 2019.

- 21. Age Wave calculation compares a man who works full-time uninterrupted and a woman who works full-time except for periods of caregiving, each earning average wages for their gender, based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic News Release, Usual Weekly Earnings Summary, January 17, 2020.

- 22. Anne Tergesen, “Bankruptcy Filings Surge Among Older Americans,” The Wall Street Journal, August 7, 2018.

- 23. Deborah Thorne et al., “Graying of U.S. Bankruptcy: Fallout from Life in a Risk Society,” Indiana Legal Studies Research Paper, 2018.

- 24. National Coalition on Aging, “Older Adults and Debt: Trends, Trade-offs, and Tools to Help,” 2018.

- 25. Lynn Stuart Parramore, “Why Bankruptcy Has Become a Rite Of Passage for Many of America's Seniors,” NBC News, August 9, 2018.

- 26. Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, “The Impact of Intergenerational Wealth on Retirement,” 2017.

- 27. Laura Feiveson and John Sabelhaus, “Lifecycle Patterns of Saving and Wealth Accumulation,” Federal Reserve System, 2019.

- 28. Laura Feiveson and John Sabelhaus, “How Does Intergenerational Wealth Transmission Affect Wealth Concentration?” Federal Reserve System, 2018.

- 29. Transamerica, 19th Annual.

- 30. Transamerica, A Precarious Existence.

- 31. Kerri Fivecoat-Campbell, “Will Tiny-House Communities Help Middle-Class Homebuyers?” Next Avenue, April 29, 2019.

- 32. Nancy Collamer, “How to Make Money from a Hobby in Retirement,” Next Avenue, July 3, 2018.

- 33. Katherine Roy and Yoojin Kim-Steiner, “Three retirement spending surprises,” J.P. Morgan, January 21, 2019.

- 34. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Americans' Perspectives on New Retirement Realities, 2013.

- 35. “Fixed & Indexed Annuities Poised For Growth Amid Volatility In Equity Markets,” Advisor Magazine, April 4, 2019.

- 36. Samantha Smith, “Most think the ‘American dream’ is within reach for them,” Pew Research Center, October 31, 2017.

- 37. “Senior Housing Wealth Reaches Record $7.14 Trillion,” National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association press release, June 24, 2019.

- 38. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Home in Retirement: More Freedom, New Choices, 2014.

- 39. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, “Housing America's Older Adults 2018.”

- 40. Greg Greeley, “Ageless Travel: The Growing Popularity of Airbnb for the Over 60s,” Airbnb Newsroom, October 1, 2018.

- 41. “Equity release market rises 8% in Q3,” Equity Release Council press release, October 28, 2019.

- 42. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index, 2000–2019.

- 43. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey, Section 11.

- 44. “Health Care Price Check,” Fidelity Investments press release, April 2, 2019.

- 45. U.S. Federal Reserve System, Survey of Consumer Finances, 2016.

- 46. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Finances in Retirement: New Challenges, New Solutions, 2017.

- 47. Genworth Cost of Care Survey 2018.

- 48. Melissa Favreault and Judith Dey, “Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016.

- 49. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditure Projections 2018–2027,” 2019.

- 50. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Finances in Retirement.

- 51. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Health in Retirement: Planning for the Great Unknown, 2014.

- 52. Ibid.

- 53. Ibid.

- 54. Howard Tischler, “2017 Data Breaches Are a 2018 Danger and Beyond,” EverSafe, February 15, 2018.

- 55. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Leaving a Legacy: A Lasting Gift to Loved Ones, 2019.

- 56. Tim Hewson, “Are there even fewer Americans without wills?” USLegalWills.com, 2016.