CHAPTER A-1

Quantifying It

As we inducted new students to their degree in music production, we would find year on year that something odd happened. These induction sessions often began by posing one simple question: “What is a music producer?”—the same single question often asked at their interviews. The answers from both the interviews and the hour-long induction discussion ranged from bizarre to more obvious. One such odd one was “miracle worker,” another was “the fixer” whilst others revolved around the more standard “make things sound good” or “make sure the band don’t get too drunk” among many other attributes.

After many years of few concrete answers we set about asking whether we could externalize what we thought music production was, the way the degree saw it, and the way the institution perceived it. We realized no one really answered it. That is, answered it the way we might answer it.

This book is our response to that. It seeks not to express how to record a guitar, what chords to play in answer to the last chorus, or whether to change the song’s tempo from 120 to 140 bpm. What Is Music Production does represent the often neglected additional skills and actions undertaken in the course of a producer’s day.

WHAT IS MUSIC PRODUCTION?

Music production over the years has become a term that refers to a multitude of different skills seemingly thrown together to create a role. However, this role has developed far beyond its understood meaning of just some 15 years ago. Therefore we can simply deduce that the role is ever evolving and emerging. In order to get there, we need to take a quick look at some of what has come before.

Looking back to before the mid-1960s, the role of producer consisted of being a fixer (booking artists, musicians, and studios), A&R (Artist and Repertoire), plus the ultimate manager of time and resources. We acknowledge that Sir George Martin is perhaps an icon for change to this model, and many may still naturally cite Sir George Martin as the best example of a music producer. Martin was already very successful (leading the Parlophone label with a number of classical recordings and comedy artists such as Peter Sellers, Peter Cook, and Spike Milligan) before taking on the Beatles, who had been turned down by other labels.

His work was to develop and nurture the creative and musical forces within the Beatles, to such an extent that many considered him to be the fifth member. He arranged and wrote string parts and was involved in some of the technical processes behind the sounds that were created. Martin focused his skills on producing the Beatles for many years and created a new perspective on music production, which would have a long-lasting effect. Many books have followed this exceptional contribution, and we will not dwell on Martin’s career specifically here, but what effect he has had on the producer’s role.

With no disrespect to Sir George, nor to the superb work he has achieved, it is no longer possible to identify him as the best example of music production as it stands today. It is perhaps controversial to think like this, but the role of the producer has come to mean so many different things today, something we hope this book explores.

In Sir George Martin’s many influential years with the Beatles at Abbey Road Studios in London, he developed a working relationship and style that became arguably perceived as modus operandi for many years, and to some extent many rock and pop genres today still follow this lead—so much so that we refer to this style of work as that of the “traditional producer.”

THE TRADITIONAL PRODUCER

We refer to the traditional producer as someone who has been allowed creative control of a recording process. For example, we would presume that a traditional producer working throughout the 1960s to the 1980s would have been used to working sometimes with a larger engineering team consisting of an engineer (if required or chosen) and perhaps a tape operator and/or assistant engineer. Their role would be to capture and encourage the performances of the artists using the options available to them. The producer would be the soundboard for the artist: someone to bounce ideas off and to receive an objective opinion from.

So what is music production then? Is it what existed before the ‘60s? Is it what George Martin and his contemporaries created? Is it the excesses traditionally attributed to the ‘70s and ‘80s rock culture? Or is it something completely different?

So what is music production?

“A lot of the concept of record production and what a producer is has really changed in the last five years… What makes you a record producer these days?”

British Producer, Tommy D, in interview.

We have concluded, through our research and discussions over the years, that guidance is a common denominator. Producers guide the process, guide the people, nurture the talent, and enhance the music. This book is thus a guide to that activity. A guide to guidance, if you like.

In the traditional sense, the producer’s creative role is to develop the artist’s music to a level at which it can be realized. This realization could take the form of being a commercial release, where the impetus is sales and exposure, or it could take the form of being artistically realized, in that the impetus is to achieve something unique or innovative whether it sells or not. Either way the producer’s role is important and often misunderstood for those outside of the career. To suggest that the role is a solely creative force in the recording process would be incorrect. There are many other aspects less fun and influential that are just as important, which we’ll cover as we go through the book.

“I’m a producer”

During the first session of an evening course we taught, we held a jovial introductory session where each student introduced who they were and why they were in the course. Students simply responded, “I’m a guitarist in a band and I wanted to learn how to get better recordings.” There is nothing wrong in that statement, as that is partly why the course exists. Others said, “I’m a producer.” In the past no exception would have been taken to that term, as we interpret two meanings of it. However, it does display a marked change in the way in which music creation is now perceived and carried out. One assumes a producer (akin to that of the traditional producer) would not require such a course. This helps to highlight the important fact that there are two meanings to this term.

Bedroom producers, as they have become dubbed by many, have indeed become not only hugely successful in their own right, but have also shown the world they are true producers in the historical sense of the word when they have come out of the bedroom. One such example, if the media hype is to be believed, is Chipmunk (a.k.a. Jamaal Fyffe) who at the age of 18 began an album with a friend in a bedroom, and with some slick assistance (perhaps from a seasoned producer and engineer) created the 2009 masterpiece I Am Chipmunk, upon which were the hit UK singles “Oopsy Daisy” and “Diamond Rings.”

Another famous early example was White Town (a.k.a. Jyoti Mishra) who created “Your Woman” in his Derby home in the UK, which made it to No. 1 in 1997. However, in fairness, there have been many albums recorded at homes prior to this (think Les Paul, for example), but this shone the light squarely at what could be done with very little money and a bedroom studio married with modest modern digital technology.

The seemingly derogatory term of bedroom producer has been born over the last decade or so and it seeks to describe the person who sits at home, plugging away at a sequencer (or as it has developed to these days, a digital audio workstation or DAW) “producing” music. Let’s be clear—the word produce here can be used in its meaning of making something sonically as opposed to guiding its creativity.

David Gray began his career based on several albums worth of recordings in a bedroom studio. One track, with some of that “slick” assistance and vocal rerecordings, created what became “Babylon” on White Ladder”(1999). “Babylon” went on to become the bestselling single of all time in Ireland and led to a Best New Artist Grammy Nomination in 2002.

The term “producer” took on a new meaning for many with the huge rise of dance culture during the ‘90s. It was cool to have decks and claim to be a producer in your spare time, with many actually making music their career. This was an explosion based out of new musical technology such as the widespread availability of sequencers, samplers, and synthesizers all communicating by MIDI. Naturally this book touches upon the art involved in this type of production, as it is music creation in its own right and should not be dismissed.

Whilst we discuss this type of producer from time to time, it is important to consider the context and therefore the role of the traditional producer is more our main focus, as well as where things have come from, and the art of production. The mystique and skills therein are explored, so that they can be utilized by all producers whether in the increasingly competent bedroom or in the elaborate studio complex.

The role of the producer

To try to define the role of the producer is to try to comprehend the sheer range of skills and attributes that come together. One could suggest it essentially encompasses a wide range of skills in one job title combined with some incredible pressures and vital talent. In some ways the pages of this book are a good example of this. Fingering through the contents pages will give a flavor of the wide range of activities and skills required. These range from musical skills, to audio engineering, consultant, counselor, financial manager, project manager, and so on. We spend some time in Section B looking into this and later in pertinent chapters along the way.

The creative input of the producer is unquestionable. The produced style of the music, artistically positioned within its genre of the time, could be the trait of that producer, something we refer to later in this book as the producer’s watermark. This watermark is placed on the music either deliberately or subtly, giving it an identity bigger or more substantial than the component parts. From the producer’s perspective, this is their trademark and could be considered their calling card. The saying is often recited, “you’re only as good as your last record” and can be held true for so many producers of the day who then are relegated to the amusing, yet apt, “where are they now pile” (Spinal Tap, 1984).

Seriously though, we can all identify with an album from our youth or many years ago that still holds value in our hearts. This will perhaps be partly because of the association with our lives at the time, but much of the value may come from the quality of the music and its production at that time. Spotify, the free music streaming service, has been a revelation as it allows the listener to revisit music long since packed away with the age-old vinyl record collection in the loft. The dust has been cast aside and this material now breathes with new life. Yes, we dare admit much of it was pretty awful and it deserves the dust, but much can assist in identifying production gems, highlighting skills and processes which simply worked for that time, place, and genre.

Recognizing and analyzing the producer’s watermark in more depth is something that will take place later within this book. However, at this initial juncture it may be helpful to offer an example watermark that can be clearly heard on the material of the Irish band The Corrs. Robert John “Mutt” Lange’s influence is very self-evident on the album In Blue (2000), which he not only produced but also wrote/cowrote several songs. In comparison to their earlier album Forgiven Not Forgotten produced by David Foster (1995), In Blue has a much more commercial pop sound, an attribute arguably created by “Mutt” Lange’s watermark.

The producer’s watermark is something that will endure with the material. As previously mentioned, it is almost their calling card, but analyzing the watermark more closely shows that this is an intrinsic set of skills, or attitudes to differing situations. Each musician, each song, each arrangement, and each studio will have incredible influence on the outcome. The mastery of the producer in every situation is key and is thus the creative backbone of this book. To begin with we need to get a handle on the types of producer out there.

Production is a very multi-faceted, yet critical, role. The reason why our prospective undergraduate students found it hard to answer the question “what is production” is because it is so hard to define and even harder to write a job description for.

This is our inspiration. Throughout this book we will look toward the process and roles the producer has taken on to get the gig or complete the gig. There is a lot of glamour and intrigue that surrounds the role, attracting many to its doors. However, it is not for the faint-hearted and the responsibility is immense once over the threshold. Once through the door, though, it can be the best job in the world.

Broad types of producer background

The producer’s creative input can manifest itself in many forms, from getting down to the nuts and bolts with the musicians in a rehearsal room carving the music into a ready form for tracking, to taking an engineering focused approach, using the technology and the studio (and studio time) to develop the artist’s material. Burgess, R.J. (2005) accurately highlights a number of types of producer. Burgess described these types as songwriter producer, music lover producer and engineer producer. These are fantastic classifications and ones we employ to some degree here. However, for the purposes of this book and our teaching we boil this down yet further to two main simple types: musician producer or engineer producer.

We have taken the liberty of rolling the music lover producer into one of the other camps, dependent on the skills that producer picks up on the job. For example, Burgess makes the case that there are those producers who come to the fray through loving the music and what they’d like to hear. We suggest that many music lover producers will develop either a strong sense of musicality or their engineering skill and knowledge.

Whether their skills develop in either area, it is common for the quality focus of the producer to be honed in either on the music and the musician or more biased to the engineering. An example of the musician producer would be Trevor Horn, while a good example of the engineer producer would be Hugh Padgham, as suggested by Burgess.

Hugh Padgham’s career blossomed in the 1980s working with artists such as The Police, Genesis, and their solo counterparts Phil Collins and Sting, among many others. His engineering skills are profound to many and has led to his work being widely analyzed. Synchronicity by The Police is one such record. Phil Collins’s legendary gated reverb drum sound is also Hugh’s achievement, or stumble, or even fault, as many would disingenuously blame these days. How wrong! To Padgham’s credit, this was immensely popular, and broadly imitated at the time and this has its rightful place in production history. This trademarking of Phil Collins’ drum sound arguably provided Padgham with one of his professional watermarks.

The type of producer you are, if you can indeed categorize, will of course suggest areas of concern for your work. Hugh Padgham during the 1980s and 1990s had the fortune to work with exceptional musicians who had strong plans for their music, support from their labels, and could in turn work with an equally exceptional engineer/producer to gel the team. Padgham slotted into this role thoroughly, producing a raft of top charting albums which to his credit still sound great to many.

It is therefore natural to argue that a musician producer might spend much more time concentrating on the musical development of the artist and subcontract the engineering to a trusted partner they’ve worked with before. Looking at the long tenure of producer Trevor Horn, he has employed a whole raft of exceptional engineering talent over the years, leaving him to concentrate on the music as a musician producer predominately.

One such intern was Robert Orton. Now an independent mix engineer, Orton spent nearly a decade with Horn as part of his engineering team working on a wide range of chart-topping albums. His work was defined in the engineering and mixing of the productions leaving Horn to concentrate on the musical development in terms of composition, arrangement, instrumentation, and textures he’s so renowned for.

Orton is somewhat different insofar as he is an engineer with a very solid musical background. Orton, a pianist in his own right while also being a trained sound engineer and music technologist, bridges the gap between the engineer producer and the musician producer when he takes that mantle. Nevertheless, his role as an engineer while working with Horn required him to focus on being creative with technology whilst leaving Trevor to work his creative magic on the music itself.

Completing your A-team

Whether an engineer producer or a musician producer, the team you surround yourself with will enable you to succeed, or perhaps fail. George Martin had access to world-class songwriters, musicians, and all of Abbey Road’s engineering staff (the likes of Norman Smith, Geoff Emerick, Ken Scott, et al.). Would the Beatles have been as successful had Martin decided for whatever reason to have somehow independently recorded the projects himself in a period when independent studios were still relatively rare? Would Hugh Padgham have made a success of so many of those large scale ‘80s artists had it not been for the production circle his role completed with the likes of Sting, Phil Collins, et al.?

As we will discuss later in Section B, the network of people you can draw upon will become the free-flowing team you’ll call upon in production situations. Using your favorite engineer or drummer for a production, whatever the material, is very likely based on experience and perhaps social currency.

Therefore, skills in developing relationships, teams and communities of practice can be invaluable for the success of producers. In this book we’ll also look at these aspects and consider how important it is to develop these connections.

Essentially there is no need to state your intent at this stage as to whether your strengths are in musical aspects or engineering ones. Begin to consider the network of people around you who will complete your team, your circle, and help you in the areas where you’re less experienced.

Production outlook

The descriptions above discuss how the professional focus of the producer is revealed. However, it is how they apply their art that is of interest. Their outlook on music production is something to consider at each turn and, as with all interactions with other human beings, we’re constantly learning. The studio is somewhat of a melting pot and can often bring out new skills and sensitivities in producers. Later in the book we discuss how to integrate with people in the studio and how to get the best out of the production team, the artist, and the musicians around you.

Some producers take a very hands-off approach to their work, leaving their artists to crack on with the music at hand, perhaps believing that the artists may need less intimate direction than other less experienced artists. Other producers may choose to guide and be the fifth member of the band throughout. How the producer integrates with the artist will neatly depend on the type of artists, the level of additional support they may need or the type of music itself. Reading a situation or scenario so as to interpret the level of intrusion or impact required is a significant talent that must be a part of every producer’s skill set.

In preparation for this book, we have heard from some producers that have described their involvement in some projects as being very minimal. There are, however, producers who we know have taken quite a leading role in the shaping of the final music, producing its every essence. It all depends on what is required and what the terms of the agreement may be.

Naturally it is very hard to make any one-size-fits-all statements, only to identify the common denominators for many of the producers we’ve spoken to and we’ll leave it for you to develop your toolkit and your outlook. We have taken the decision not to use quotes from all of our interviewees for this book but to analyze common threads, thoughts, and outlooks shared by the vast majority at different stages of their careers and in different genres. It’s their outlook that counts, not the anecdotes for us.

Your outlook will be based considerably on the type of producer you are, whether you get on easily with people and can be cool and calm in times of high stress. Developing this outlook will assist in your development as a producer. The ways in which you communicate and describe things will be of importance later on.

Backdrop

Historically, the role of the producer has been that of someone who has managed the project from the finances, studio personnel, musicians, and the product as a whole. Production (for many a traditional producer) was the management of the session and as such typically not always the glamorous role that many associate with production. It could be argued that the process was much more restrictive both creatively and financially. Allied to this, unions such as the Musician’s Union in the U.K. then stipulated that all musicians be paid in three-hour blocks. For this reason many sessions would either be three or six hours long. The fable has it that once the three-hour session was over, musicians would stand up and leave mid-song unless another three hours could be paid (how things have changed in rock and roll at least)!

Many musicians, especially some session musicians, who are called in stick to such M.U. rules. Expect this from orchestras and quartets and the like.

In early days of recording many sessions were seemingly limited to this time-frame, based on the belief that nobody really needed more. The aim of the game was to capture a well-rehearsed performance. The production would have taken place beforehand in rehearsal (pre-production as we now know it; see Section C). Added to this, the expectation of highly polished productions using technology was not the norm. Well-recorded, honed, and well-performed, yes, but produced a little less than by today’s technologically intensive standards. One could argue that the polished productions expected by today’s music industry have shifted the focus from this type of pre-production to production and postproduction, where the knowledge and use of technology now plays a greater part in smoothing off the edges after rather than before the record button has played its part.

Today’s producer

Today the word production appears to allow different connotations or a wider range of activities than it once did. The diversity of musical genres has now thrown aside the traditional model, allowing for people who, quite literally, physically produce the music to be considered as producers. Using the traditional model, an artist would have been the writer/performer and the producer would be the producer. Nowadays artists can blur those lines, becoming co-producers, and the producer can take some part in the songwriting and performance.

Change the music to recent dance genres, such as trance and house music, and the word producer will inevitably mean the writer and the producer combined. The interesting thing here is that, within the trance and house model, much of the music is likely to have been produced alone with little or no human interaction in terms of someone to physically produce, other than perhaps a solo session vocalist.

Additionally, it is interesting to note that many of the compositions that lie behind dance music genres such as trance require as much effort and skill as traditional songwriting. The difference comes in the fact that a song can be written with an acoustic guitar and be developed to the full complement at a later date. Within trance, for example, this might be somewhat complex and inappropriate to do on an acoustic guitar. As such the composition and production really are seen hand in hand. In other words, one cannot exist without the other; some music cannot necessarily exist without the associated technology. This can add to today’s blurring of the term “producer” from its historical benchmark.

Danny Cope, author of Righting Wrongs in Writing Songs (2009) suggests “Gone are the days, in certain genres at least, where the creative type needs a producer to make them ‘sound good’. That’s because of the tools that are so readily accessible (Logic, Reason, GarageBand, etc.) which often make it easier to ‘sound’ good before you have actually composed anything of any real substance. The process has shifted so that instead of writing something and then making it sound good, we have something that sounds good that we then need to create something with. It’s like buying the expensive custom-built picture frame first, and then having to paint an exquisite painting to fill it.”

Needless to say, the historical production role still remains to some extent. There are many albums created using that traditional production role, but the pressures are very different now, having changed subtly bit by bit over the years. For this book we’ll continue to focus on the traditional role and from there how it has evolved since. Musicians performing as artists, bands, and ensembles will be with us forever and while they record singles and albums, the objectivity and assistance a music producer provides will always be required.

The lifestyle of the producer these days has changed too from those early days where you once belonged to a record label or recording studio. Nowadays the role is very much based on being freelance and working hard to generate business, thus often with long hours and great personal responsibility. The rose-tinted vision of the producer being in control of all and sundry, firing orders from the plush leather sofa at the back of the studio with a cigar is quite far from the truth. Producers, in our experience, are hard-working, innovative (in the studio and in business) affable and entertaining people with plenty to say about their love of music and the way in which it can be developed.

Their working lifestyle is something we’ll approach later in this book as we discuss navigating the freelance role and the ups and downs of working in the studio.

The recent climate

The current music industry is a very competitive environment financially, yet there is more music available than ever before. This is mainly due to the widespread availability of music production equipment in the past decade or so. The average home computer is able to develop high, often studio-quality, productions with the correct know-how. That know-how is the all-important aspect and something we encourage people to experience and brush up on. This book describes some of the things it takes to be a producer.

This financial climate is squeezed at the top end and as a result the artist development that was so important to the sound and identity of so many bands has been seemingly reduced in many labels. Artist development whether from the label, artist manager, or elsewhere has been paramount to artist success.

To say that artist development does not carry on inside the labels would be disingenuous, as many artists do of course get the treatment they need. However, the prevalence, we suspect from what we have learned, has been far reduced. The supposed hedonistic excesses of the ‘70s and ‘80s within the rock and pop scenes have ceased to exist as we knew them. During this period, very large budgets indeed were poured on productions in the relatively safe knowledge that many artists would recoup the money from sales.

It could be said that the industry was then in a healthy state. Producers were often given complete scope to mold and produce their artist’s music as they saw fit with some intrusion from the labels. Some seminal albums discussed within this text were produced in this period.

Among the heavyweights on the rock scene in the ‘70s and ‘80s was Queen, a band best-known for their musical prowess, lush vocal arrangements, and unique sound. As producer, Roy Thomas Baker certainly had a daunting task of steering and molding Queen’s creativity in the studio. However, time and money was more abundant compared to the climate of today’s music industry and therefore spending many days just recording Brian May’s multiple guitar parts was often a reality.

This luxury of time in the studio environment enabled Roy Thomas Baker and the members of Queen to experiment with different recording techniques and sounds and produce anthemic rock tracks such as “Killer Queen,” “Don’t Stop Me Now,” and the monumental “Bohemian Rhapsody.” It is interesting to consider whether such tracks could be produced within today’s time and budget-conscious climate, even with the speed that advanced technology affords us.

However, over the years and more recently, the record companies have suffered some reduction in revenue through the widespread loss of sales to digital downloads and digital copying, a topic we investigate a little in Section C. This, in turn, has changed the way in which artists are developed and delivered to the marketplace. It is not uncommon for a good quality demo to be placed on the shelves with some minor changes. The aforementioned album from David Gray, White Ladder, is a fine example of this. The demos were rebalanced and all the vocals rerecorded, but the organic package was too precious to alter. This strategy proved to be correct, making the single “Babylon” a Top 5 hit in the UK.

A slightly different but interesting situation occurred in the U.S. in the mid-’90s with the band Jars of Clay, who while playing together at college submitted a demo recording to a talent competition. Upon winning they were given the opportunity to play in Nashville. The buzz from the performance coupled with the popularity of their original demo saw record deals being offered from labels. Further down the line the demos were rerecorded in the studio for their first album (self-titled Jars of Clay) and the band have since gone on to be multimillion selling artists with two Grammys to their name.

These changes in the current music industry climate have led to many other avenues or types of signing. Many genres have sprung up and remain quite small in terms of sales and clientele, yet have sustained a solid following for many years. Such diversity has only been prevalent for a number of years now and offers musicians and aspiring producers the opportunity to get their music heard.

In conjunction with new websites offering distribution, it has never been easier to have a professional presence without a recording contract per se and reach the public. Other methods have allowed for many bands to continue with their careers, without the machinery of big labels. One such example is the U.K. band Marillion. They have used many different methods in recent years to enable them to write and produce their next album. Anoraknophobia in 2000–2001 was one example. In 2000, without a contract or the money to release a physical album themselves, they decided to use other methods. The one big leap for them was to email their fan base via the website to ask them if they would be prepared to pay for an album up-front. This was very successful and enabled them to make a record for their fans, paid for by their fans.

Although not a new method by far, a recent example of DIY can be seen in the career of folk musician and songwriter Seth Lakeman. Lakeman’s self-written and produced solo album Kitty Jay was allegedly recorded at home for just £300. Lakeman is now signed to the record label Relentless and has received much critical acclaim and success.

Another facet of the technological explosion is that producers of a different variety have emerged. For example, despite rap being entrenched in popular music culture for quite a while since the 1980s, its now enormous mainstream emergence in the U.K. was given a boost by Dr Dre and U.S. artists such as Eminem. Dr Dre is both an excellent producer and businessman, having brought many major selling acts to the fore. Within this genre, it is important to demonstrate the right sound, impact and base upon which the rap resides. Dre mastered this to a fine art.

To compare radically differing people such as George Martin to Dr Dre would reveal some interesting disparities. Not simply their upbringing, education and musical tastes would offer differences, but the management of their artists would be completely different, as would their business dealings.

It would therefore be fair, and obvious, to suggest that differing musical genres require different treatment, and in most cases a different producer and production team. There have been few producers that have spanned a wide variety of genres. One example is Robert John “Mutt” Lange, who has worked with pop act The Boomtown Rats, to soul/pop Billy Ocean all the way through to the heavier rock of AC/DC and Def Leppard and more lately based within country/pop, producing his former wife Shania Twain.

Throughout this book we will try to give examples of the industry as it is now and how this affects the role of the producer. However, we are mindful that the industry moves so fast and that some examples will be less relevant than others. Therefore, we have selected those examples that we believe demonstrate the discussed matter well and thus the information can be transferred to a wide range of situations. We have placed sources of interesting comment and further reading in Appendix F-1 –the tape store.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROCESS

Understanding what is required

It is always interesting to read interviews with the major producers in the trade magazines. They are portrayed often as having planned out the work they were producing. However, this is unlikely to be the case every single time. Only so much preparation can be completed prior to recording. So many artists now write in the smaller studio and as such the production happens there and then as an iterative and integral process. This is of course so much easier by today’s standards now that we have nonlinear editing and all the gadgetry.

However, planning is something everyone can improve upon, and in many a music production it can be vital. We spend some time in Sections B and C looking at the behind-the-scenes work of a music production and the preparation you may need to consider.

In earlier times, producers had only preparation to guide them to a successful conclusion. Often limited by the three-hour block of time, the producer would use an arsenal of skills to prepare the music for the session. This understanding gives way to arrangement organization. Phil Spector is regarded as one of the masters of this with his work in the ‘60s. He would place musicians around a large live room to create a large, almost orchestral, “wall” of sound.

A well-known example of this painstaking arrangement methodology is “River Deep, Mountain High” by Ike and Tina Turner (written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich). The large ambient wall of sound that can be heard in this track and many others not only became Spector’s production watermark but also a trademark of the era. Incidentally it is documented that Spector worked Tina Turner hard during the recording sessions in order to achieve the desired energetic and powerful vocal delivery. This attention to detail was based around what we refer to as the producer’s CAP (Capture, Arrangement, Performance), which is covered in Chapter C-4.

The brief

In so many assignments, a brief of sorts may be given or directed by the label’s Artist and Repertoire (A&R) department (see later in this section for more information). Somewhat inaccurate folklore would have it that the A&R department will throw in a brief something along the lines of “This band needs to sound a little like Oasis, with lots of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, with a splash of Norah Jones thrown in during the choruses.” Perhaps this is a bit too flimsy and diverse an example on our part (and with no offense to the artists who are incidentally held in good regard by the authors). We agree that it is an extreme example of the directions you may be pulled in as a producer. Realistically, of course, you will be able to discuss a better and more suitable alternative route.

Your incentive may be that “you are only as good as your last record.” This is all you have to go on. The manipulations from either the A&R or the band may conflict with your ultimate plan for the band or artist in question; you will try to reconcile this with your ultimate plan and direction for the band, while making great music, which is, after all, what you’re in the business to do.

This conflict may happen internally for the most part and thus cause a lot of deliberation. However, a conclusion is required, and therefore it is often necessary to be rather visionary at this stage. It is important to bear in mind that not all productions require over-production. Sometimes, as with a mastering engineer, it is often best to live by the adage that “less is more” or better still “know when to do nothing at all.”

Many producers, we often think meddle with the music presented to them, not because it needs it but because they feel that they need to be seen to have produced it. In their eyes, this means altering what is there. One producer we spoke to was amazed when he was asked to work on a band’s next album because of what he didn’t tell the band to do!

In this instance the band recognized that the production sage might opt to alter many minor elements and that was critical, meaning the producer maintained the rights to the production credit. This less-is-more approach is critical to success.

There are so many artists out there who simply do not require the high production so often applied to them. They can carry their own. Even Peter Gabriel in 2010 called in Bob Ezrin (producer for many artists including Pink Floyd) to assist him in the production of Scratch My Back—not as the producer, but as almost a production consultant. In this instance Ezrin’s brief will have been to support and assist the development of the album.

Rupert Hine, while speaking with us, discussed how he has started working in a way that could be described as a production consultant. He now works with some artists remotely. The artists will send Hine MP3s of the musical development and he can then reflect and discuss with the artist, steering the musical outcome.

Artist & Repertoire?

A&R have received a bad reputation unfortunately, not least because the tradition of A&R is said to be lost. These departments were once responsible for bringing the artists together with their songwriters and producing a format and a buzz. For example, Frank Sinatra did not write his most notable material. It would be partly the duty of the label to source material and songwriters for artists and match them together accordingly.

So what changed? Well, as artists began to write more of their own material (the Beatles being an excellent example), the A&R person developed to survive. In doing so, they continued to act as the talent scout but also, as Neil Peart in his 2004 book Traveling Music puts it cynically, A&R may meddle with the music based on the label head’s guidance. “[It’s] the kind of meddling of the ‘business’ in the ‘music’ that always bugs me.”

But let’s spare a thought for our colleagues in A&R. Their careers are insecure with high turnovers of staff. Again the adage “you’re only as good as your last record” (or in this instance, “signing”) is applicable here. Consistency is lacking and as a result reputation and the artist development has been under some jeopardy.

It is widely believed that A&R meddle in mixes and final output based on a whim, or a musically inept perception of market influence at the time, which may in turn jeopardize the music they are attempting to promote. Therefore the role of the A&R department is often understated and undervalued within the marketplace by both employers and the music fraternity alike. A great shame, perhaps? We need to look far more closely at the issues surrounding the record labels and the current investment levels in new acts before we should judge too rashly.

The term production

“Production” can be used to describe so many different things these days. In this book we discuss production in two ways:

First is what we would naturally refer to as music production, which is an expression of the creative and artistic development of music both in and out of the studio. While this book does not intend to address the whole gamut or any specific creative and artistic elements of music production, it does deal with the back-office work and the day-to-day life that the producer undertakes.

Second is the production process itself. By production, in this latter instance, we refer to the process of producing an end product: the making of the CD; the making of the media that sits on a server for download through an online store; the physical medium perhaps not yet decided upon which will convey our music to the masses in the future, if a physical medium is even needed at that point.

Any creative, yet commercial, process resulting in a final product can follow a model similar to this. It is worth noting that this is by no means exhaustive and variations can be the norm.

This latter reference to production is the process we outline within this chapter. Each stage of the process has its own innate history and has developed into a well-oiled machine that responds with innovation to change and style throughout time.

The production process

Anything published, whether a book, a magazine, a movie on a DVD, a website, or an audio CD, must follow some kind of production process. In this instance, we do not mean music production per se, but some kind of production process, as defined above (Blu-Ray? SACD?, etc.).

This production process has, for whatever artistic output, been carved out from initial trial and error, and through painstaking refinement, to create and define the present systems and procedure we rely upon today. Any artistic process can follow a generic model, similar to the one shown here. In this example, we’ve identified seven rough stages of the production process.

To produce a creative work, an idea must flourish, or the desire to capture an experience. So often, many of these ideas fall by the wayside, but from time to time, they will make it to the drawing board. The composition of the music is mainly outside the scope of this book as we make the presumption that, as a producer, you’ll be working with an artist. However, it must be pointed out that in this day and age of 360° deals, producers are having to protect themselves and their income streams. As a result, the clever and insightful are beginning to engage much more in the writing process. We discuss income streams and 360° deals later in the book.

The next stage in the process is pre-production. In this book, we dwell for some time on this topic, looking at its importance and some approaches that can be employed to improve productivity in the remainder of the process. Preparation for any creative project can seem to detract from the art form, but in the case of any production, there is a business side that needs to be considered and supported.

It is imperative that planning is given equal value, or equal consideration, when contemplating a project. Is the project viable? How should the project begin? Who should be involved? These are all valid questions that require valid answers before commencement (or sometimes during): Answers that will inform the rest of the process and the ultimate success, both financially and artistically.

As with any art, it needs to be captured so that it can be portrayed. Paintings need a canvas upon which they can be structured and later viewed. Music requires some form of canvas too. This can of course be manuscript using traditional notation, or a sound wave captured in either digital or analog form. The captured work needs to be structured or formed. In music production and recording terms, forming means mixing so the elements can be balanced accordingly. For the painter, this would mean less red, more light, and so on.

Postproduction as a stage in the process is the first stop on the mass-produced train track. For a painting to be mass-produced, or copied, it must be encapsulated first. Once copied it can then be prepared for mass-production. Any edits in light, color, or shade can be applied to ensure a maintained quality across the various mediums (postcards, posters, prints, etc.). It is the same for music. Music needs to be prepared for the medium upon which it will be presented, or mass-produced. Additionally the quality can be improved, or balanced, at this stage.

Next in the process is the production itself—the way in which the mass-produced material is collated and reproduced. Replication, distribution, and marketing are things that are of least interest to the artist compared to the inception, composition, and capture of the art. However, it is imperative for the mass-produced reproduction to retain as much quality as possible. Equal interest should be paid to this part of the process (as it is in this book).

Traditional roles in the studio

The roles of the production process have remained broadly the same since the inception of the recording studio. Naturally much has changed over the years due to the necessity of some maturing in the process, but also because of the advancement in technology and the ability to bring so many roles into one should that be necessary. Some artists and producers still have a strong preference to have a larger team than simply one engineer/producer.

Historically, sessions were attended by a small group of specific roles with large responsibilities in each department. The sessions would be managed by the producer, and in attendance would be an engineer, an assistant engineer and/or a tape operator. It would even be possible on some larger sessions for more than one engineer or assistant engineers to be present. The equipment might, of course, require this, as the tape machine should be attended to regularly and managed. One slip-up here could cause loss of that perfect take, so to manage this at the same time as a mixing console would (in a time before auto-location and memories, etc.) be perhaps too much. As such the division of roles was very structured and simple to comprehend.

These structured roles have been used in our teachings for many years, as they allow not only a sensible division of labor within the control room, but also engender sensible educational group work—something that is so crucial in this industry. The advent of the computer, with its own onboard mixer, has naturally blurred these strict lines. No longer is there one mixer in some studios, but two. For example, Robert Orton chooses to mix completely “in the box” within Pro Tools, simply resigning the SSL on most occasions to no more than a stereo volume control via two faders (a 2-track return essentially!).

Recording sessions these days can be managed by one person if desired. As previously mentioned, modern studio equipment allows the engineer alone to manage and develop the session if required. Therefore three or four engineers are no longer required in each session, but just the one if necessary. Additionally, this person could be the engineer and producer rolled into one.

Therefore, the roles in the studio will alter dependent on the session ahead. A simple acoustic recording or rock band perhaps can be managed by one person alone, while an orchestral session will require you to engage a number of assistants to simply move between the control room and the live room to alter microphones.

Historically the producer would, as we will explore in this book, be in charge of the production process, timings, and artistic direction. The role encompasses the financial side of the production in addition to all the nitty gritty project management we’ll explore later.

The engineer, meanwhile, would preside over the management of the audio signal through the console through to the multitrack machine, ensuring it is tracked appropriately. In addition, the engineer would ensure that the session runs smoothly from the perspective of the engineering team. Alongside the engineer would be the assistant engineer, ensuring that the microphones are placed accordingly and that the musicians were helped in achieving the sound required. Naturally the role also would be to help track signals if required, amongst a whole plethora of other activities.

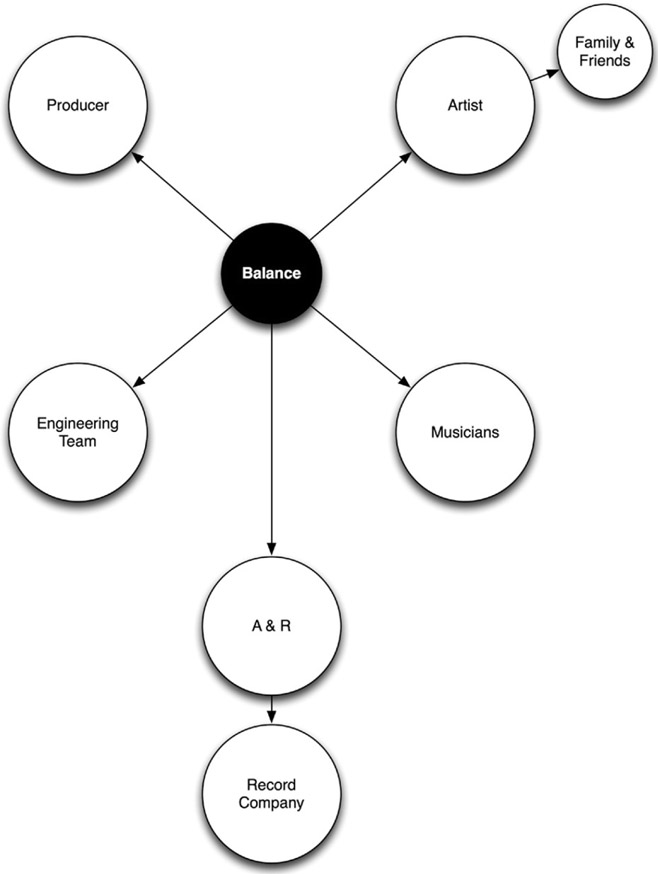

The traditional hierarchy in the production team within the studio. Additional roles can be appended as required, or indeed removed.

It would not be uncommon on larger sessions for a tape operator (tape op) to be present. The role of the tape op would be to manage the multitrack, ensuring that the tape is aligned to the heads, the tape machine is cleaned, and may ensure also that track sheets, take sheets, and other information about the session are stored appropriately.

Tape ops have often had some of the ‘lesser’ jobs in the recording studio, hence nicknames such as “tea op” for their ability to make the all-important ‘cup of tea’ (possibly coffee in the US!) during sessions. Their job descriptions have often left a lot to be desired, from having to work on reception overnight, through to providing errands for the band and engineering team, to gathering various uncommon supplies, that some consider essential to the smooth running of the session. (This has perhaps more recently been replaced by the studio ‘runner’.)

Climbing the ladder

Getting on the traditional studio structure was an apprenticeship style route where a budding engineer might begin as a tape operator if lucky, or just as a member of administration staff such as receptionist. When an opening to operate the tape machine came, the young engineer would step up to the role. Many stories emanate from the studio of assistant engineers or engineers either not showing up to work or being ill, leading to a hierarchy shift where the assistant engineer would step up to the engineer mantle, while the tape operator would step up to assistant.

This folklore, while very true, is less the case these days given the aforementioned changes in technology and the personnel structures that surround it, but also due to the reduction of studio space these days. Assistant engineers are still very much part and parcel of the larger studio spaces.

The times are changing and records are made in new interesting ways these days. However, in the major recording studios in the U.K., this is still a typical career structure for some. Those who embark on this route into the career are inducted and are trained thoroughly in their activities and are able to network throughout the industry from the very first spell on reception.

Others perhaps come into the career at differing points of the hierarchy. Robert Orton came to prominence via a different route. He started working at London’s Phoenix Studios, then in the former CTS studio building in Wembley, as someone who would be around the studio to help and assist on the larger sessions. He made sure he learned as much as he could about Pro Tools, looking over the operator’s shoulder and picking up all the tricks he could!

Regrettably as Phoenix was given its orders to move out to make way for the new Wembley Stadium development, Orton looked for new work and landed on his feet, becoming part of producer Trevor Horn’s team at Sarm Studios. Early days would see him managing Horn’s Pro Tools rigs, backing up files, and managing the systems. This led very quickly into Orton running some sessions on the computer and having a go at a mix which Horn liked. In partnership sometimes with other engineers at Sarm, he shared mixing duties on albums for artists such as Seal, Pet Shop Boys, Robbie Williams, Captain, Tatu, and Enrique, among many others. Since leaving Sarm he has paired up with producer RedOne and has mixed for many current artists such as their Grammy award-winning work with Lady GaGa.

Orton has a unique experience where, still relatively young, he has achieved his perfect role as a freelance mix engineer. Orton is lucky, as many still work in assisting roles in the main studios for many years before gaining the opportunity to move up the ladder.

Some of course transcend the ladder and enter the role of the producer at very different places. Some become producers from the mainly musical route, such as Brian Eno, Trevor Horn, Rupert Hine, and Bernard Butler, to name just a few. However, we must point out their personal fascination with what technology could offer them!

Their route is often a less secure transition somehow. There have been many successful artists who have tried to move over to the role of producer and have not quite managed to do so in the mainstream. Other people, through self-producing, are then given the opportunity to produce artists based on their own personal success and this has become a more common route as time goes on.

However, the true development for the future will be the producer’s ability not only to manage the production process and the music, but also their ability to find, develop, and write with the artist in a longer term arrangement. Many producers are understanding that this arrangement is a more certain way of receiving an income from the work placed in, as both advances from labels and record sales are actually meaning a reduction in real terms in income.

This arrangement will allow, more than ever perhaps, the opportunity for budding producers and engineers to make a go of it themselves in the absence of a supportive and powerful culture of record company support and development. The do-it-yourself (DIY) opportunities now afforded to producers through the Internet are rife and will perhaps become the industry of the future. We discuss this later in Section C.

Day to day

For former Abbey Road Studios engineer Haydn Bendall, music production is a fabulous job in which there’s something new every day. “It’s not as though I’m pulling myself into a job I do not want to do for eight hours a day”.

For many professionals, work is simply work. It’s something that happens at work and does not come home with them or to the pub or bar, for that matter. However, music is constantly all around us and there are times when one’s sound engineer or music producer ear kicks in involuntarily. The ear unwittingly digests or analyzes what is being heard, which is not something you always want when you’d rather simply appreciate, admire, and envelop yourself in some favorite music.

Life as a music professional can be different and, to friends and family, a little odd sometimes, especially when you take exception to something you hear. Here is a warning that can be disseminated to music production students: you’re always listening!

The role of the producer is sometimes framed as being the cigar-smoking wise sage sitting on the sofa at the back of the control room. However, this is a misleading image. Producers are very often grafters, or at least their teams graft with them and on their behalf, and are a truly dedicated breed committed to good, innovative music. How each producer operates will differ between individuals, but the dedication to great-sounding music is key.

Suffice it to say, the role is not all a bed of roses. There will be times when despair and frustration are normal. Difficult artists can become hard to manage in the studio and the sensitive flux that holds the productive environment together can be shattered in one less considered comment.

Producers never cease to amaze us in that they learn to transcend many of these issues. Some producers we have interviewed for this book are some of the most humble people we know, yet are also at the same time quite opinionated about musical direction. Their easy manner and honest dedication to the music gains them appreciation from the artists they work with and can often ensure the session continues smoothly.

This delicate balance between the flux of the session is something the producer becomes a master of on a daily basis. Ensuring this remains a productive and creative balancing act will result in a free-flowing recording session. We’ll cover how to develop these ideas and skills a little later in the book.

The day-to-day role of the producer is in no way prescribed and can be very varied from a meeting with a label, to meeting a new artist at a gig, or sitting with a colleague in a studio editing some vocal takes. Each day can be different and rewarding. However, at the same time editing dull and boring vocal takes can become a thankless task too. As with any role in life, there are the good bits in addition to the bad bits. The producer has some really exciting parts, and a lot of more mundane parts that are hidden from the public eye. It is these we wish to unearth in the remainder of this book.

The balance of opinion, or what we call flux, is key to success and expands upon the triangle of influence—something the producer becomes a master at managing on a daily basis.

“We’re not that important in the big scheme of things” says Haydn Bendall of the music producer’s role.