CHAPTER A-2

Analyzing It

FORMING AN OPINION

As with many art forms, critical analysis is a way of life. To form a view of another artist’s work is not only necessary for personal professional development (learning, listening, developing a personal ‘watermark’), but also for producing future artists and positioning them in their particular place in the market.

To be appreciative yet critical of colleagues’ work is a necessary evil of becoming a practitioner. When we say “critical,” we do not mean a type of horrid negative critical disapproval, but an academic and professional critical approach. This could be conceived as a method by which you benchmark the music or audio in front of you, or in which you can break down the construction for future use in your own work. Some critical analysis will be not simply of the music and its construction, but also social and cultural aspects too: how the music fits in the genre, how the music represents the times, and so on.

It can be difficult to form a proper opinion of a recorded piece of music. You’ll note the addition of the word “proper” in the sentence before. This is where the difficulty lies. It is very easy, in fact natural, to either be attracted to something or be slightly repelled by something, whether that is a fellow human being, a piece of art, or a music production, for many unknown reasons.

These opinions are partly what form us as individuals and allow us to have engrossing discussions on our chosen subject matters. However, what is a proper opinion? Why do we feel attracted to one person, or another; one piece of music or another? Some things just press the right buttons, irrationally or rationally, consciously or subconsciously.

It is important that emotions should not dominate us, but guide us. Objectivity is a powerful and desirable attribute for people of all positions and fields. Understanding the point of view of others and their artistic philosophies is a necessary, some might say crucial, skill.

Balancing a subjective opinion with an objective one can be extremely helpful and something we all must learn to manage. For example, many producers will speak of creating a vibe in the music, or extracting this aspect of a recording to enhance its immediate attraction. This feeling might be based on the subjective and personal emotional response of the producer. It is natural for musicians to go with this feeling, run away with it if you like, and allow this to guide the session. However, it is the objective view that might prevail to place a reality check on proceedings, placing the material back into current trends and the marketplace.

In some ways, the subjective and objective views can cross in that you may objectively allow yourself the opportunity to subjectively be moved by the music (as though a member of the buying public) by means of a test. Does this dance track make me dance? Does this metal track make me want to rock my head? Does this chill-out track make me chill?

These are all fairly subjective and sometimes irrational responses to music, but these things move us. They make us tap our feet, turn up the stereo, drive a little too fast, nod our head, and so on. Music simply moves us. These are the sentiments and the triggers, often unexplained, which make us become musicians, producers, or simply music lovers.

This fascination raises all kinds of questions which we’ll not attempt to address here now, only that to be able to switch this on and off can assist you as a producer. An emotional listening switch if you like.

Being able to control these emotions for your advantage as a producer may become something that is of great value as a skill or commodity. To be able to listen as though you were a member of the buying public (music-lover), while having knowledge that what you hear in that state can feed directly back to you as a producer, in some ways provides instant market research.

Wouldn’t it be useful if we could tap into some instant objectivity, or instant market research, by employing a personal emotional listening switch? No longer would we listen as a default industry professional, but perhaps as a music-loving member of the buying public.

Many might say that forming an opinion based on what you like, or what moves you, is very subjective and could be misguided. It could be argued that successful business can take place only with a cool, calm, shrewd look at the marketplace and with good management. This appears unemotional, as in many businesses, art is not at the core of day-to-day trading.

Music is rather strange in this regard, certainly the world of music production. By its very name, it is making music a product, therefore a saleable item. It automatically combines art form with marketplace: something produced by love, later sold for commercial benefit.

The picture painted above almost suggests that art sold for financial gain goes against the grain. However, this marriage of art for commercial success has become the trademark for many producers.

Stock, Aitken, and Waterman spent successful years seemingly producing hit after hit for any new artist who came along. It almost did not matter whether the artist could sing, but only whether they could sell records appropriately. That misconception is what many cynically believed. However, this era launched many long-lasting and highly successful careers, most notably Kylie Minogue, already a successful actress in the Australian soap Neighbours. There is no doubt from the interviews we’ve held, that she can sing!

Other producers have been highly successful in marrying the art form of music production to commercial success with assembly-line precision. Trevor Horn could be listed here for succeeding with a wide range of artists over a lengthy career. More recently Mark Ronson has developed a producer’s watermark which has been successfully applied to many artists’ work ranging from Amy Winehouse to Duran Duran. Many producers have been successful in this regard and across many genres, Robert John “Mutt” Lange being another.

By no means does this apply universally to all their work. There will be the albums you’ve never heard of or had the pleasure of hearing. Haydn Bendall, engineer and producer who has worked for many leading lights such as Paul McCartney, Kate Bush, George Martin and countless others underlines the often forgotten (in the industry) absolute importance of the artist. He quotes for example, the fact that on one record the producer can do no wrong and produce an amazing album for one artist. With the next artist, using the same mics, studio, desk, and so on the story is completely different. Bendall makes the point that the artist still can and must have a huge sway on the success of a project obviously from the songwriting perspective as well as the performance. The producer can only do so much. The producer’s arsenal of abilities will be more popular in some years than others and because of this one will go in and out of fashion. Keeping abreast of current practice is an ongoing pursuit not restricted to simply the music industry.

One skill a producer has, or should have, is the ability to be decisive and form solid, articulated, opinions—some might even say opinionated! Analyzing this rather negative word with all the connotations we expect from everyday life suggests that we should attempt not to be too opinionated and not to impose our thoughts and wishes on others. This obviously is transferable to the world of the music producer, but some etiquette remains. Haydn Bendall asserts “…we’re an opinionated bunch. Well, we’re paid to be so. To make decisive decisions is our business. If we’ve got it wrong we’d be the first to admit something is not working, but we like to try it out first.”

Therefore, the producer’s opinion is of increased value to the production of music. Some artists will require that firm artistic hand to interpret their work. Peter Gabriel writes in the sleeve notes for his 2010 album Scratch My Back that he set out some criteria for his arranger to work with. He indicates that to offer an artist a blank sheet can sometimes be the worst kind of freedom. Placing some restrictions can be the way in which we develop to overcome the rules. Gabriel is right and we speak later about serendipity and that restrictions can mean outcomes!

Forming an opinion is an important attribute. How else will you know what to repair, modify, scrap and so on? How we manage our conviction is another matter. We believe it is important, as you will tell from many sections in this book, for a producer to be an exceptional listener while also sympathetic and intuitive to clients’ needs.

Form an opinion. It is absolutely necessary, but should be drawn from both subjective and objective frameworks dependent on the task at hand. But be open, objective, and able to admit you’re wrong all at the same time. Managing this is something that takes time to master and understand. The following sections relate the ways in which we can listen to music in so many different ways and on so many different levels to give us the edge and an open, objective, and modest viewpoint.

DETACHMENT

So how should you be guided through an opinion? By your gut feeling or by some rational objective view? Well, this might be up to you. There is a detached way of listening that is good to try to develop. When listening to music, it can be difficult to detach yourself from the subjective, enjoyable aspect of the song you’re listening to (the head nodding, the foot tapping). After all, this is the reason we’re all in this, because we love music. So what are we talking about? It can be difficult to form a professional detached opinion of a piece of music you grew up with, or feel is somewhat second nature to you as a member of the music buying public.

Your reason for enjoying this piece is because it was something special to you at the time, perhaps even employing a hairbrush as a microphone! You were perhaps not a music professional then. In any case, the music would be something you appreciate for its art, its style, and simply to enjoy. As the music professional within you grows, you can begin to develop the ability to listen outside of that enjoyment bubble that the track generates and analyze the piece accordingly for all its merits and flaws.

We see this as a kind of switch that can be turned on or off as necessary. However, many music professionals report that they have had periods of finding this switch hard. One engineer we spoke to said that he could not enjoy music for a number of years as he would always be in analytical mode constantly and unable to let go.

Obtaining this switching ability is extremely helpful, as it assists the music professional to engage in the two types of listening, from the enjoyment aspect and from the detailed aspect, providing it can be controlled.

It is not simply about detachment. There will be some times when you may have to work on material that you do not enjoy, that is perhaps out of your comfort zone. This is where a detached, objective ability to listen and react will be of great benefit.

Within this chapter we investigate some ways of listening and how to begin to delve into the world of analyzing already produced music.

UNDERSTANDING LISTENING

Let’s state the obvious here for just a second: listening skills are an integral part of the music producer’s, indeed the music professional’s, portfolio. However, it is, as always, not what you’ve got necessarily, but how you use it.

If we were to canvass all the producers and engineers in the world, we are sure many of them would not profess to have perfect hearing by any stretch of the imagination (listening for long periods at high SPLs can take its toll!). Neither would they all profess to have perfect pitch, because they don’t.

However, they would all claim to be able to listen. Listen intently. Listen accurately. They might also claim to be able to hear how they wish things to sound before they’ve heard them. Therefore it is what we refer to as ways of listening that interest us later in this chapter. Some are perhaps born with the skill to be able to hear and listen in a detailed way. However, many of us have to train ourselves in the ways of listening.

There are many websites and products offering to teach you methods of how to listen in different and new ways similar in nature to ear training software, such as Auralia, which focuses on identifying pitch and chords within music. However, we’ve found one of the best ways of learning to listen is to actually listen. If you’re a new producer or engineer just starting out, simply buy a trusted pair of common monitors (in our day this would have been a set of trusty Yamaha NS-10M Studios and to many a pro they still are). Listen to as much music (or everything) through them, set up in as decent an environment as possible: minimal reflective surfaces with the monitors forming an equilateral triangle between themselves and the listener.

The premise behind this is that your ears will develop a transparency, or an affinity, or relationship, with those speakers in a good nearfield environment, the very same environment that you could replicate in any studio you might wish to work in using your own speakers.

The benefit of this is that you will always have a trusted set of monitors with you wherever you go, allowing you to produce results quickly and efficiently (or indeed you can research the monitors used in the studio you most use). You can do this because you’ve listened to all your reference material on the same speakers (and hence focus on every single element) plus you also know the voicing of the monitors (how certain instruments stand out; for example the NS-10Ms would elevate vocals out of the mix a little).

This can put you in the zone, making a transparent connection between your ears and the music (in other words, less concentration is being spent on real-time compensation for monitors you do not know). This in turn should allow you to make more confident decisions without needing to listen as often to any reference material you may have, thus maintaining focus on the music at hand and saving valuable professional time. In these days of high quality active monitors, amplifier selection is less important, but should you be employing a passive set of monitors, then amplifier selection can also be critically important.

Getting your monitoring environment right is also key, and regrettably outside of the scope of this book. Nevertheless, it cannot be stressed enough how important it is to ensure that your listening equipment and environment is as solid as possible. Good monitoring in a good room should provide an excellent listening environment. Remember, assessing music and its components in anything less might skew your thoughts and actions later in your own work.

You may wish to emulate the conditions you find in the studio by completely listening in a nearfield environment. If you have nearfield monitors place them at the same height and orientation you’d have them on a meter bridge, thus experiencing things as they’ll be when working hard on the session. Some engineers have spent their careers carrying around all sorts of trusted loudspeakers for their projects. Famously, Bob Clearmountain has for many years employed a set of Apple computer speakers among various sets of mixing monitors with award-winning success!

Now here comes the caveat. This might be a good way to train, especially if you are interested in the engineering side of the business. Many producers will use other systems and environments as their check. Many use their car stereo systems, as these can be one of the most common listening environments despite their poor reproduction characteristics. Lets face it, many producers spend a lot of time in the car between sessions, meetings, and gigs. Really, it is a case of whatever works for you. If there is a motto in this area, it would be to be confident in what you hear.

So what do you do if you’re working in a studio with different sounding monitors and have not got your own to hand? Well, you employ your reference material.

It can often be hugely impractical to move your monitoring rig around from studio to studio with you for every project you work on and therefore you need a reference point which can help you be educated to the tone and color of the monitors and acoustic environment in which you’re working.

It is popular to carry CDs (or non data-compressed .aiff or .wav files) of a selection of well-known (to you) tracks across a number of genres. These tracks might have aspects that simply work. One track might have an inspirational acoustic drum sound which can often be a point of guidance while tracking or mixing. Another track might demonstrate full dynamic range and also have a fantastic blend of instrumentation; this material might simply be an excellent mix. This excellent mix can then become a blueprint of the relationship to the differing frequencies you may expect in the mix and may choose to emulate. Of course there are many fantastic benchmark albums you could employ for this. Some might choose seminal albums such as Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, or Def Leppard’s Hysteria.

One thing this reference material should permit you is the ability to discern the characteristics of the new monitor and its environment. On listening to your well-known reference material you might note that the treble is quite exaggerated while the mids are subdued, leaving vocals in some ways less present in the mix. With this assessment on board, you can compensate for your lack of empirical knowledge of the monitors in question.

One way to have this to hand, should you be engineering, is to have the CD (or other player) connected to a two-track input on the mixer so you can easily switch between your mix and your respected reference material. Naturally we ought to bear in mind that the reference material will be mastered, but you should be able to work around this, bearing in mind that your dynamics should be allowed to breathe perhaps a little more than the mastered version is. The frequencies and so on can remain a consistent and reliable guide to your work in the sessions.

These simple, yet time-tested, tools can improve your productivity in the studio as your sonic decisions may count on it, should you choose to work this closely with the engineering side of things.

Many people still confess to mixing on headphones. There are many arguments that suggest this is not such a good idea, but as the buying public are spending more and more time on their earbuds perhaps this is something professionals should consider as routine when checking mixes.

How the record-buying public listen

Music professionals, it is argued, should strive to be confident in what they hear and be able to make appropriate assessments accordingly. We’re sure that many professionals would prefer to be using their treasured monitors and listening environments to make such assessments. We must, however, all recognize that the buying public listen to music on a wide variety of equipment, formats and modes.

As such it is surely the goal of any production team to ensure that the music being produced should be intended for the equipment on which it will be played. Well, yes to one degree or another. Dance music should, it therefore follows, be intended for the club PA, while the singer/songwriter’s delicate album might be best placed for the earbud headphone.

Cross checks are also required. It is important for both sets of material to translate to as many different listening environments as possible, including the car, and to sit together if segued together on radio side-by-side.

A large debate has begun and continues to rage within professional circles about the way the public listens to music at the current time. There is no dispute that the generic MP3 player or phone has begun to dominate the listening market. It comes with some fairly inexpensive earbud headphones with reasonable reproduction. Some professionals are thus concerned that the listening public may never hear the music in its intended sonic form over loudspeakers and in a high enough resolution.

Meanwhile, the second most popular environment must be the car, which can be rather unpredictable. However, many engineers and producers still ensure that their material works in the car by taking the material out there during mixing, and even mastering, sessions.

Therefore, some might recommend that professionals begin to benchmark their material using the same systems. Using an iPod for monitoring might seem wrong, but might be good to see if the mixes are translating as one might expect. The NS-10s of the future?

DIGITAL AUDIO, IPODS, AND SO ON

The arguments rage on. The music-buying public vote in force that downloads, and the data-compression currently used, are the way they choose to consume music.

Until this point the music lover has had to import her CD into a library and the file format would most likely be MP3 or similar to save space on storage capacity on both the host computer, but also her iPod.

It is rare that the CD would ever be listened to live again and perhaps most likely will have been simply stored. As a result, many people are finding downloads (legal or otherwise) convenient as it can be fast, saves a trip to the shops, and the quality (MP3/M4A) has become acceptable.

File formats generate a great deal of discussion insomuch as they do not deliver the full bandwidth of the music. Some rudimentary calculations would tell you that a basic MP3 stores around a fifth of the data that a CD would, depending on the bit rate. This is achieved by some quite clever data compression. In brief, many data reduction systems work on a range of principles and result in either lossless or lossy methods (see the Glossary for more information).

One interesting principle is based on the presence of frequencies that we do not concentrate on in the presence of adjacent loud ones. In other words, the frequency spectrum is chopped up into lots of bands. If one of those bands is loud at any one point, it is likely that the two adjacent bands on either side are less important. Using some fairly sophisticated algorithms, the encoder will manage these and perhaps choose to omit them for a number of samples, thus saving the amount of information recorded. Naturally this principle of auditory masking is actually more complicated when employed, and readers should be directed to The MPEG Handbook by John Watkinson (see Appendix F-1) for more information.

An argument still exists that CD is not a high enough quality. Whether we like it or not, professionals spent many decades prior to MP3 striving to improve the sound quality and to some the CD allowed a solid delivery medium to the consumer of high-quality reproduction. The CD for the first time omitted the flaws associated with poor styli and turntables where pops and scratches had an analogous effect on the sonic quality. Many simply feel that the resolution of both the sample frequency and bit depth are not enough.

The iPod and its culture have changed this perception. In order to squeeze material onto limited storage capacity or to be able to transmit it across the Internet, the MP3 format was adopted and lately the better sounding MP4/AAC codec.

There are many within the industry who currently hope that the day will come when it will be possible to download full bandwidth material at perhaps higher bit depths and sample frequencies than CD’s 44.1/16 (44.1 kHz sample rate and 16-bit word length; see Glossary for more details).

In fact, the case is often argued that a new 192 kHz sample rate and 24-bit depth could be set as the standard for all multitrack audio, thus eliminating any need to look at other rates. This naturally would support high quality audio at every stage even if it did end up at 44.1/16 on CD.

What has transpired is that most engineers will record definitely to 24 bit as standard with either 44.1 kHz or 96 kHz (sometimes 192 kHz) for the sample rate, passing high-quality mixes to the mastering engineer, which are then dithered down to lower quality versions for release (CD and MP3). Please see the postproduction chapters (Chapter 12) about dithering and submitting mixes to aggregators.

Headphones (“cans”) can be a popular way of working, but many professionals do not routinely use them. To many they can present a problem for a wide range of reasons, but also provide some large positives too. They can be considered a negative as headphone units can vary hugely and in times gone by most of the listening public would not be listening on them.

Monitoring on headphones can still be a positive inasmuch as the finer details can be easily heard (with the right cans of course). This latter point is the reason that so many still employ high quality monitoring headphones for this purpose.

The quality of the headphones can always be disputed whether that be the drivers themselves, or the headphone amplifier driving them. Either way, production teams seemingly prefer to use professional monitoring systems when working.

However, there is a compelling argument that we put forward in this chapter that much of the music-buying public consume their music using in-ear headphones on the move and as such we should monitor for this market! What are your views?

HEARING

Introduction

Our hearing system—our ears and how we process the information they provide—are undoubtedly the most precious tool of our trade. The ears are delicate devices and should be respected and utterly cherished. In this section we’ll be looking at how the ear perceives sound in an irregular and nonlinear fashion and how this affects the way in which we work with and listen to music.

As you would expect, we’d be remiss by not touching on hearing loss a little. But before we can do so, we believe it important to delve a little into why we hear the things we do in the way we do, not necessarily in a scientific or medical way, but from a practical stance that allows us as music professionals to appreciate the variety of ways of listening and how they affect what music we produce.

Human hearing

Listening is dependent on a complex device, and even more complex to comprehend interpretation. The device is of course the ear. The interpretation is of course what we consider our auditory perception: the way in which our mind interprets the information it is provided from the ear.

These two elements, working hand in hand, continue to pose quite a few questions. Recently the medical profession has begun to understand how we hear and interpret sound a little more. Research into auditory perception has improved the codecs behind the data-reduction systems we’re all familiar with. There appear to be around the corner, at the time of writing, some new codecs that might provide much-needed sonic improvement.

Let’s take this part by part and look at how the ear works and what aspects we as producers would do well understanding while working in the studio. Understanding those reactions that the ear/listening system demonstrate when under certain conditions can improve your perception of how your music should sound, but also how it will be consumed.

Therefore, in this little section we’ll be looking at the signal flow, if you like, between the sound creation, ear, and what we understand of how the brain interprets the sound we hear. This section is not intended to be exhaustive, but a guide. In Appendix F-1 at the end of this book you will find many books for further reading which we recommend.

As we’ll discuss later, there are reasons why we’re prone to turning the volume up and up and up as we groove to a favorite record. There are other reasons for wanting to turn it up in the first place. Before we can make a true assessment of the listening, which we will do later in this section, we ought to be confident in understanding the symptoms of our hearing system.

The ear

The ear is split into three important sections. It is important as music professionals to understand a little about these functions and how the ear operates under certain conditions.

The outer ear is the start of the story. The pinna is the fleshy exposed part of our ear. The next part is the concha which attaches the pinna to the ear canal. People refer to this collection of parts as the ear itself. This is only one, yet important, aspect of the ear.

The ear’s story begins with the outer ear, which contains the pinna, concha, and the ear canal providing two exceptionally important functions: funneling sound into the ear and directionality, among other things.

Have you ever wondered why we can identify a sound from behind us, from even above us, or even below? Well, much of this is down to the pinna. This exposed receptor provides us with clarity to sound coming from the studio monitors exactly positioned to hit them while you’re sitting in the hot spot. However, for sound coming from behind the head the pinna provides some dulling in the higher frequencies. This therefore provides our brain with one piece of information that tells us the direction from which a sound might be coming. Another indicator is the time difference as a sound reaches one ear before the other.

Next in the chain is the ear canal. The concha and the ear canal combined offer the ear a boost at high frequencies of roughly between 2 to 6 khz, depending on the person (see Equal Loudness Contours and Perception). A purpose of this is not so clear but it is plausible that this is to ensure maximum sensitivity to the frequencies of our human conversation.

This proves an interesting point for us at this stage. The ear is a nonlinear device, being somewhat more sensitive to some frequencies than others. As such it is worth taking a small amount of time now to understand the effects of this and how this might impact on the music we record and produce, the first of which is explained in the sidebar on equal loudness contours and perception.

EQUAL LOUDNESS CONTOURS AND PERCEPTION

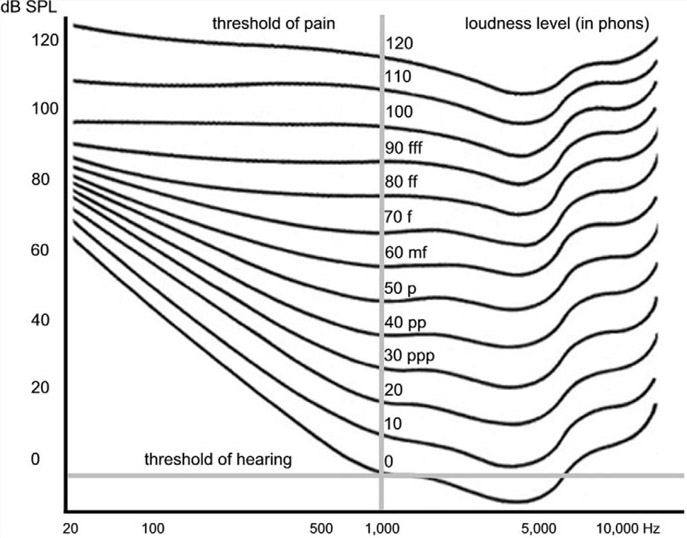

In the 1930s a couple of scientists engaged in some research attempting to appreciate how the human ear perceived frequencies against other frequencies across the spectrum. Their research culminated in the equal loudness contours.

Fletcher and Munson’s equal loudness contours precisely tell us why we need to be wary of the term volume as we work. The louder we turn up the volume the flatter the ear’s response.

Fletcher and Munson set out to understand how much louder any certain frequency would need to be perceived as loud as the same perceived frequency at 1 kHz. The 1 kHz frequency is considered the center frequency between 20 Hz and 20 kHz—the human hearing bandwidth.

In equal loudness contours, the phon refers to a level at 1 kHz, thus in the diagram above, the 10 phon curve is the curve where all the frequencies have been perceived against 10 dB at 1 kHz. A 20 phon curve would be one measured against the perceived loudness of a 20 dB sound at 1 kHz and so on.

By testing a number of young people, Fletcher and Munson concluded that at varying different levels the amplification required to perceive frequencies at the extreme ends (low frequency and most high frequencies) could be large. For example, in the 20 phon curve (a 20 dB signal at 1 kHz) a gain of an additional 40 dB would need to be applied to a 30 Hz signal for the ear to perceive this at the same level.

This set of contours demonstrates two immediate things. Firstly that the ear appears to be most sensitive to frequencies in the 2–6 kHz range. Secondly that the ear’s perception to sound is less linear than we might expect.

As you can see from the chart above, as the curves get louder, the perception of the listener becomes more equal, requiring less gain to frequencies at the low and high ends. This is of course of interest to the work we do because, as the listener turns up their tune, it will sound different to them.

We can never really automate these changes, only estimate their effect on what we hear. For example many hi-fi manufacturers have tried to overcome this feature. The first is the common “loudness” button found on most systems these days. Its purpose on introduction was to increase the bass and treble to assist those on lower volumes to perceive the bass and treble a little more, thus overcoming the Fletcher and Munson curves.

However, the increase in bass and increase in treble would remain static as the listener increased the volume on their favorite track, thus making louder versions very boomy and bright.

We remember Yamaha introduced a variable loudness control in the 1980s which would start from the max position (labeled “flat”) and work backwards. As you pulled the control backwards not only would it attenuate the sound in the mids accordingly, but it would increase your perception of the Fletcher and Munson curves.

This was a neat idea rather than the on/off affair we are mostly left with today. This feature alongside bass boost in addition to the dreaded hall/pop/classical selections do nothing to necessarily improve the output of your music, but are regrettably important for music professionals to somewhat consider when working.

Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone’s hi-fi system was set to an optimum level so that music was perceived the same loudness in every setting? In Bob Katz’s book Mastering Audio (Focal Press, 2007), he points out that this is the case in all cinemas as all the systems are set for THX, a surround sound protocol, and as such the level perceived in each movie theatre will be the same. Even Katz uses a set level in his control room for his mastering work. This is set to the 83 phon curve as it is where the ear is nearly the most flat. This is the same as the THX standard.

Again, how does this affect us in the studio? It is easy, as we’ve both been there, to get into the “vibe of the session,” as Tim “Spag” Speight calls it, and to fall foul of wishing to crank up the volume on the control room monitors.

Every time we do this, our ears’ perception has been altered and it could be argued that the brain needs to compensate a little. We’re not suggesting that a standardized volume be used, as in the recording world this can be rather difficult to maintain, but an appreciation of the issues that raising the volume can produce is critical.

At the end of the ear canal is the tympanic membrane (more commonly known as the ear drum) sealing off the outside world to our sensitive middle and inner ears. The membrane is flexible and has the important function of acting as though it were the diaphragm on the most precious microphone of all. This receives the sound waves brought down the ear canal and, just like a microphone, converts the movement of the compressions and rarefactions into mechanical movements handled in the middle ear.

The middle ear connects the tympanic membrane to the inner ear, where all the processing takes place. One of its functions is to impedance match the incoming signal to the ear. Another is to help compensate for loud signals by acting as an attenuator.

This impedance matching is handled by the ossicles. These consist of a set of bones called the hammer, anvil, and stirrup. This clever little set of mechanics matches the rather free flowing sound in air that arrives at the tympanic membrane with the rather more resistant fluid within the inner ear.

Within the middle ear, there are a number of muscles which manage some ear protection. Their function is to resist the movement of the ossicles under loud sound pressure levels. In some ways you could consider this a limiter of one form or another.

THE ACOUSTIC REFLEX

The acoustic reflex is the effect in which the muscles within the middle ear contract while receiving loud sounds. A sort of limiter, if you like, for the protection of the fragile inner ear.

The acoustic reflex has another effect on the listening of a music lover. If the ear is exposed to loud sounds for a reasonable period of time, the acoustic reflex will kick in and the threshold of hearing for the ear is shifted higher. As such, more sound will be required to break through the instigated protection the acoustic reflex provides.

There is a funny link to this and how we listen to music. Many of us have been there where we’ve put on an album we really like and we’ve started to listen at a reasonable level. As track two kicks in and it starts to move you, you increase the level a little more. Track three arrives, and as the killer single off the album, you crank up the track. The fourth track starts powerfully and you creep up the volume a little bit more. By this point you may have been exposing your hearing via the hi-fi speakers or iPod headphones to high sound pressure levels for over 15 or 20 minutes.

It is at this sort of point that hearing damage can occur, but also it is critical that we understand how this affects the way in which we listen. Marry the Fletcher and Munson curves with how this has affected the acoustic reflex and threshold shift. It is clear that we want to turn things up to make the music move us, but the reason we want to do this is possibly because our ears are already trying to protect us. As we’ve already established, the louder we turn it up, the more frequency response of our hearing system alters. It is proposed that this might cloud the way in which we assess what we’re recording or mixing.

The inner ear is where the main business of translating the sound arriving at our ear is turned into some kind of information that our brain can comprehend.

After sound has been converted into mechanical movement by the ossicles in the middle ear, this is then translated onto the oval window of the inner ear, known as the cochlea. The inner ear is enclosed and contains a fluid suspension all curled up in a snail-like structure.

The middle ear contains the hammer, anvil and stirrup which together are termed the ossicles. Their functions are to transmit power from the ear canal to the inner ear while also protecting the hearing system from some damage.

Hypothetically, opening this snail-like structure is like unrolling the Oscar’s red carpet; we find something called the basilar membrane. The basilar membrane is the listening tool of the ear. Its function is to be the receptor of sound. “The Cochlea is the transducer proper, converting pressure variations in the fluid into nerve impulses.” (Watkinson, 2004).

Actually the basilar membrane contains a number of receptor hairs on it and on this set of hairs are a further set of hairs called stereocilia. These are the true receptors of the sound we hear.

The basilar membrane, if rolled out in a hypothetical linear fashion, is a frequency receptor that senses high-frequency sounds near the start of the cochlea working toward the end, which is low frequency.

Opening up the inner ear and hypothetically rolling this out like a carpet shows the basilar membrane and its connection to the middle ear.

So, along the length of the basilar membrane there are sections that receive certain frequencies. It is therefore important to note that if hearing loss occurs at one frequency, it is perhaps logical to conclude that this element of the membrane has been damaged.

As we have already established, the ear appears to listen to music in terms of small bands. The frequency response of the ear is split up into what are known as critical bands. These critical bands are considered the lowest common denominator of divisions the ear can discern apart easily.

Hearing loss

Hearing loss has always been with us, usually from the loss of upper frequencies as we grow older or in those unfortunate enough to have been exposed to loud mechanical devices (perhaps in factories) for long periods of time over the years.

Our current understanding of hearing loss alongside new, tight, health and safety legislation ensures workers are better educated and protected as much as possible from permanent hearing loss in the workplace.

For music professionals, the knowledge of hearing loss is better understood too. As such, many employ some rather excellent molded in-ear defenders in live music situations which attenuate frequencies as equally as possible, as opposed to the early stuff-them-in types which reduced high frequency.

For performers, the same technique has been employed in a way for in-ear monitoring, which no longer necessitates a set of powerful and loud wedge monitors at the front of the stage. The in-ear monitors can eradicate sound outside of the ear and allow a pristine musical mix in the in-ear monitors. In addition, they can be turned down (if desired) to reduce the exposure to high sound pressure levels that damage hearing.

There are a number of types of hearing loss on the ear mechanism, as described below.

Conductive hearing loss is essentially the middle ear’s inability to move freely in the presence of thickened fluid. This is usually caused by infection or packed earwax. This usually can be repaired and medical attention should be sought.

Sensorineural hearing loss is more serious as this is where the inner ear is irreparably damaged and can no longer send the appropriate signals to the brain for certain frequencies. This type of hearing loss can be induced by too much loud exposure to sound but can also be induced by illness or physical damage to the head.

Mixed hearing loss is, as the name suggests, a mixture of the two previous types of loss. Meanwhile, unilateral hearing loss is where there is hearing loss to one ear. This can be a hereditary condition, or can be caused by external symptoms such as infection or damage.

The above hearing loss types produce effects on the ear and the perception of sound. In the music industry, noise induced hearing loss (NIHL) is probably the most common type of loss. Much research has taken place in recent times about the loss of hearing and its link to prolonged exposure to high sound pressure levels (SPLs). Listening to high SPLs for long durations of time should be avoided, as well as keeping the monitoring level down and taking regular rests from the control room.

HEARING LOSS TIME BOMB

Could there be a hearing loss time-bomb just waiting to happen? Essentially the relatively modern phenomenon of listening to music on the move via the Walkman in the ‘80s through to the iPod and other generic MP3 players has possibly given way to more intense and regular sound pressure levels being induced on our ears than ever before. Add to this the open backed construction of the typical headphones used in these situations. Thus, in order to hear the music more clearly, you simply turn up the volume to drown out the conversation on the bus or the train noise as it throws itself through the subway.

We wonder what effect this will have on the listening public later down the line. We propose a nonscientifically based set of rules (of thumb) about listening with open backed earbud style headphones. The first rule of thumb is that if someone sitting next to you can hear your music from your headphones then this is too loud for you. The second is that if you cannot hear the conversation around you in some semblance of clarity, then it’s too loud!

WAYS OF LISTENING

Many people refer to something known as the cocktail party effect, a phenomenon where the listener finds themselves in a crowded room, perhaps a cocktail party, with significant background noise. All the listener’s focus is naturally on the conversation with the person in front of them. This is an amazing ability to discern noise subjectively dependent on the focus of the conversation presented to the listener.

However, concentration on their topic can suddenly be broken by the sound of their own name or something that catches the mind’s interest and the listener’s head turns. This suggests to some extent or another that, although we’re consciously concentrating on our own conversation with the person in front of us, subconsciously we are able to listen and, more critically, process some key aspects of the background noise enough to be alerted to key words that interest us.

These abilities are ones we as producers and engineers utilize a great deal, whether knowingly or not. There are many ways one can interpret this cocktail party effect described above. We can conclude, perhaps, that the listener’s mind is always listening to everything whether they wish to or not, while being able to discern the most interesting conversation in front. Can parallels be drawn from this hearing ability to many who focus mostly on the vocal in their favorite pop song?

Can we also conclude that there is a lot of audio information (in the party and any piece of music) that is missed, or simply not appreciated or processed? Is this a shame? Perhaps in a musical sense it is, as the listener does not always process all the sounds coming toward them.

This is, of course, one premise studied and adopted in part for complex data reduction algorithms, allowing us to reduce full pulse code modulation audio (PCM data is the term often referred to as CD quality with no data compression) to smaller forms such as that used in data reduction systems. Data reduction systems in any significant technical detail are outside the scope of this book, but are of intrinsic importance to the engineer and producer. As such we will refer to data compressed forms of music and how producers can deliver on these formats.

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could, as a music professional, switch between the two states of listening—listening to the person in front of you (the focus of the audio material) and listening to all incoming audio information—with almost equal appreciation?

The ability to switch between “ways of listening” can be very powerful in allowing access to vital information about the music you’re working on for a variety of discerning buyers. If you can hear the material on many different levels, then you can assimilate how this material might be perceived by the background radio listener; the listener who sings along to the vocals with that as their focus; the instrumentalist who concentrates on their particular instrument in detail; and to fellow music professionals who, like you, analyze the material in many ways. Let’s take a look at this in a little more detail.

Listening foci

CAVEAT

It is, of course, important to acknowledge that to a certain extent these different ways of listening are and can be interrelated and therefore are not clinically separated. But for the purpose of our discussion, we have made these slightly more exclusive in order to give some clarity to the subject.

Above all, we realize that experience assists greatly in this area and this is something that cannot be taught. However, at the end of the book we intend to give signposts to other authors and texts which will help you improve your skills in this area. We introduce various ideas and concepts; however, for further detail and depth please refer to the Recommended Reading section in Appendix F-1.

In the introduction to this chapter, we already quickly identified some peculiarities in the way in which we listen and how our brain interprets the information it is provided.

There are so many ways we could analyze the way in which we listen to music or sound. We’d like to start with what Bob Katz, in his 2007 book Mastering Audio, The Art and The Science (Focal Press), refers to as passive and active listening. This is fairly straightforward to understand insomuch as passive listening is the background radio you may sing along to in the kitchen, and active is the concentrated focus on listening, whether that be a particular element or elements (or indeed the whole) of a certain piece of music.

This suggests the level of concentration or focus we’re giving to the music. However, what if we wish to listen to certain things or a range of things or indeed the whole of the audio played to us? For the purposes of this book the change in focus between the minutiae and the song as one entity is what we refer to as micro listening and macro listening.

Macro listening refers to a higher level of listening. If we think in terms of altitude, this would be appreciating the whole of the town’s landscape below over a large distance. This allows the listener to listen to the whole collage or sound (the song). This is not the same as passive listening, where the music might wash over you. This is focused listening, but on the whole of the content of the song as much as possible at the same time and not with any particular bias to elements. This is almost an element of detachment, which can offer you great objectivity when you need it.

Micro refers to the innate listening ability to be able to focus on singular aspects of the track (the conversation at hand when thinking back to the cocktail party effect). Using the altitude analogy, this would be zooming in on a particular street in the town landscape and maintaining focus on its surroundings.

The ability to listen actively and passively, micro versus macro, is incredibly valuable to all engineers and producers and can be honed. The ability to listen in detail to all information coming at you from the monitors at the same time is something that engineers spend years training themselves to do, but perhaps never quite achieve. Sometimes this has a negative effect inasmuch as it is very difficult to switch off. Tim “Spag” Speight, a former engineer for PWL, says “I can’t just listen to music for enjoyment. I just can’t do it”. Speight goes on to suggest that he spent so much time analyzing music that it is too difficult to switch that inquisitive ear off.

However, there can be a downside in that some engineers have reported that they cannot employ the cocktail party effect in such high background noise environments. Research suggests that the loss of this effect is to do with hearing loss (something all music industry professionals should take time to research). How this affects sound engineers and music professionals is not so wellevidenced. Perhaps it is because they have trained their brains to listen in a macro way, listening to everything at the same time and not just following the tune or guitar solo? It is advised that engineers and music production professionals get a hearing test to be sure.

Holistic listening, as we refer to it, is listening in even broader terms than macro. Holistic listening could be likened to the listening process employed by a mastering engineer when working through a project. Here she may be concentrating with macro listening (in terms of each individual track) but will also be concerned with the holistic. In this sense the holistic listening refers to an appreciation of the whole album, or program of music, as though it were something smaller and tangible.

While a songwriter might compose a song over a three-minute period, or an artist might compile an album’s worth of songs, a DJ meanwhile will mix together his selection of tunes, his set, over an hour (Brewster, 2000, Last Night a DJ Saved My Life). Within the set there will be peaks and troughs akin to the internal structure of the three-minute song, or the peaks and troughs of a well-compiled album. This is something we refer to as emotional architecture.

The different altitudes of listening can be holistic, or looking at a whole album, or program of music, all at once; macro, or considering the song at face value; or micro listening, which allows you to focus in on small aspects of the audio.

A mastering engineer works in this holistic manner by presiding over a whole album, gelling together the various tracks which may have been mixed by different mix engineers in different ways, ordering and organizing the material so that the flow is maintained.

Holistic listening skills should be developed by the producer in order to assess the overall sound of the project or album and therefore, in turn, realize the sonic aims of the project. Close links can be made with the vision aspect of the producer’s role (see Chapter C-2, Pre-production), insomuch as the sound of an artist and his album could be foreseen and understood at the very start of a project.

Developing listening foci

Developing skills to listen in these ways will come naturally to many of us. We will appreciate that we can all focus in on one instrument in our favorite song. Focusing in on something we understand such as our own instrument, or the lead vocal we sing along to, is something that will be simple to do.

Developing skills whereby you can listen to a track and analyze many of its components at the same time, or appreciate the spread of energy in each frequency band, will only come with practice and plenty of active listening.

Practice makes perfect! So how should you go about this? The next section, “Listening Frameworks for Analysis,” might be a good starting point.

To try to get to grips with listening, one must ensure that the listening environment is correct, with loudspeakers set up as suggested earlier in this chapter. The key is, as you will have no doubt gathered, to listen as much as possible. Not necessarily the passive listening we all engage in, but the eyes-shut active listening we’ve been speaking of. Closing one’s eyes can improve the attention you can afford to the sound coming to your ears. Try this as a method to gain additional focus to the suggestions below.

How do you listen? How might you choose to listen? What are you listening for? This image charts four quadrants of listening: passive and active against micro, macro and holistic. How would you plot these listening activities?

To develop skills in listening focus switching, just place a busy track which has large amounts of instrumentation on your accurately set up monitoring environment. Next, attempt to identify the instrumentation you can hear by switching from whatever your normal level of listening is and then focusing on one instrument; then zoom out to take in as much of the music as possible, perhaps even trying to get to holistic level where you’re above the music, just assessing frequencies and intensities in aspects of the sound.

While this might be perceived as a skill predominantly for the engineer, it has uses for the producer also as it hones the listener’s ability to be objective—a skill very much required for the job of producer.

Specifics

So far we’ve been mainly concerned with altitudes of listening, or ways of focusing in on what is important in a track. Focus into the relevant zoom level is one thing, but what do you do when you get there? What is it you’re listening for? What are the parameters by which you’ll analyze and use what you hear?

With micro listening we could expect to solo in on an instrument on the mixing console. How do we assess it when we get there? Do we look at the engineering: its sound, its timbre, its frequency range, its tuning, the capture, or the performance and all that entails?

At this level of listening we’ll also be concerned with the minutiae of the performance in terms of tuning, timing, and delivery. We can be very analytical when a track is soloed, concentrating on every detailed aspect of the sound, pass after pass. It is easy to enter this level of analysis when the instrument is presented to you in this manner.

How we approach separating out the same instrument when presented to us immersed in a whole track is a skill that can be developed. Again, to some this will come naturally, while in others this will have to be developed. Simply focus in on one aspect (best to try an instrument you know well, or the vocal) in a busy track and try to listen to it in isolation, attenuating the other aspects from your listening experience. This can be hard to do, as it is one signal intertwined together with perhaps another 23 tracks of audio information. However, the ability to focus and discern what that track’s worth of audio is doing, and thus its effect on the mix as a whole, will become an invaluable skill. Personal-solo, if you like.

However, once we’ve separated out the audio or instrument we wish to focus on, we need to concentrate on making an assessment of it both sonically and musically. As a producer, your role will vary from the person who says that the sound being produced is not the “right” sound for the style you’re wishing to convey through to the performance is not quite as you’d expected, and so on. The call is potentially yours to make. Therefore, it is important that you hear and appreciate what is happening with that instrument.

In a previous book (From Demo to Delivery: The Process of Production) we proposed the employment of a self-developed listening analysis framework which dissects the music into a number of headings, acting as prompts for the listener to make an educated assessment of certain parameters. We’d like to develop this in the next section by looking into each section a little further.

LISTENING FRAMEWORKS FOR ANALYSIS

Developing a listening framework for analysis is a way in which analytical listening in music production can be taught. This short section is inspired by the excellent work of William Moylan. Moylan is one example of best practice in this area. We wish to convey one method we have used to kick-start many of our students over the years into track analyses.

Example listening framework

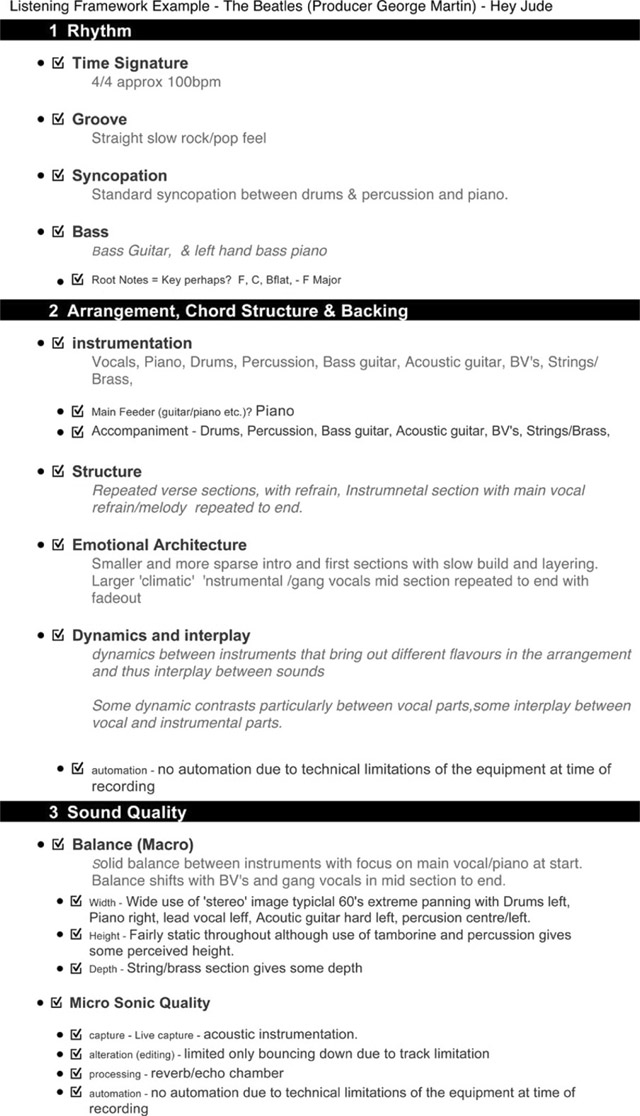

Frameworks for analysis are the starting points to dissect how a recording has been put together objectively and how its result actually sounds. Below is an example of what we might consider the bare essential elements and a structure by which listening can be analyzed. This framework will need to develop and mature depending on its use and function.

A listening framework such as this basic example can provide a checklist against which overall sonic and production qualities can be measured.

Listening with a critical ear is a personal pursuit and will vary widely from person to person. In the framework example above, we have introduced the idea of using listening passes (passes refer to the number of times the tape passes the playback head or the number of times we listen to the piece in the DAW-led world we now live in). In this example we listen three times through and break these main areas down yet further to assess them and comment on them. It should be mentioned that more passes are often required.

This branch diagram could be expanded to offer exacting questions from each of the prompts here if required. With more experience one or two passes should suffice for the simple list shown above.

PASS 1

In this example, pass 1 is entitled rhythm. The first thing that can be assessed is the form of the drums, or rhythmical elements. Analyzing this part of the recording can reveal the time signature and offers some insight into the groove of the piece. Taking this one step further, linking the bass of the song within this pass, we can learn much about how the song is constructed, whether there is syncopation, and what the bass is playing. This pass could of course be expanded to the types of rhythms and how they interact with other instrumentation.

PASS 2

Pass 2 turns attention to the more musical aspects of the recording. In this pass we’re concerned with the arrangement, chord structures and backing— essentially the way in which the music is constructed. This includes an analysis of the instrumentation. It is here that an identification of the main feeder can be made. The main feeder in a song is the instrument that drives the song. Not a vocal hook necessarily, but an element that makes the song memorable and often the main driver in the backing. It may be the catchy riff, or the solid pounding of piano chords. We look here also at the accompaniment: what makes the whole composition tick behind the scenes sonically? Finally the melody can be assessed.

The arrangement section is broken down into three elements: structure; emotional architecture; and dynamics and interplay.

The structure of the piece, if it is your own composition, is already known but as new tracks are introduced and these skills develop, structure will be an informative place to gather plenty of information of the construction of the song. It is at this stage we can identify if there are things that can be changed and manipulated.

We next assess the music’s emotional architecture. Emotional architecture is the way in which the music builds and drops. This is not an assessment of dynamics (covered next), but an assessment of how the music affects the listener through its intensity. This is something that can be drawn graphically as shown below.

Emotional architecture graph showing the intensity and power of a track as it delivers its choruses and a large ensemble at the end.

In this graph, the emotional intensity, or power of the music, can be shown and tracked. Assessment of many popular tracks can often show themes or perhaps new ideas of how to achieve this variety in emotional intensity.

Next we would quickly assess the dynamics of the instrument and how this interplays with the track as a whole; for example, the dynamics of a given instrument and how it might be integrated into the mix using automation, or other mixing techniques covered later in this book.

PASS 3

On the last pass, we assess the sound quality of the music and dissect its construction. This is split into two areas and here we introduce the terms macro and micro. In this case we refer to macro, meaning the balance of the instruments together, and micro is the focus on individual elements within the mix and their sonic quality.

Here we refer to macro listening as broad listening subsections: width, height and depth.” The first refers to stereo width and the use of panning. We would wish to make an assessment of how the stereo field has been made and constructed. Height, in this instance, refers to the use of the frequency range, or spectrum. Some artists make full use of all the frequency ranges with deep, but focused, bass and excellent detail at the top end, while other pieces choose to limit the overall bandwidth they occupy. It must be noted here that height can also refer to the vertical presentation of a sound. Last is depth, which is an assessment of the presence of any given instrument or the mix as a whole. Is the mix deep, presenting instruments that appear to come from behind others, or are all instruments brought up to the front in the mix?

As previously introduced, micro listening is an assessment of the internal elements that make up the sounds in our mix. How instruments have been captured and whether there are issues inherent in their sound can be gauged. Listening in a focused manner using a good reproduction system can also reveal edits in material that were not supposed to be heard: drums that were replaced with samples, and vocals that were automatically tuned. Estimates of the types of processing that were used in achieving the mix can be made.

Automation now plays a huge part in mixing and presenting the micro elements. Can an assessment of the automation moves be assessed on very close inspection? How does this shape the presentation of the music?

Framework analysis

Once an overview of a framework is decided on, we advise that comments be scribbled down in response to each of the areas in the framework. A personalized proforma could be created. An example has been given below, based on the basic framework given. Any proforma document should be well-designed in such a fashion that it takes little time to become accustomed to, allowing reliable information to be recorded about the song in question. How this is notated will be a personal method based on whatever can be notated in the boxes.

In time, this skill should not require a lengthy written document or framework proforma as suggested here, but something to jot simple notes down of pertinent points observed. This framework acts as a checklist that one day should become second nature.

In the version below, a rough analysis is made using the 1978 Genesis song “Follow You, Follow Me.” The analyst has chosen to write comments that might be pertinent to recording the track’s qualities. For example, a list of things to listen out for in the next pass, such as the key, which could be in some dispute. These have been adorned with question marks and can be reference points for later investigation on additional passes. Other listeners might simply wish to rate the sound and use a star rating, although this would not give exacting points for discussion or further analysis.

As discussed, this example, or method is far from exhaustive and should be expanded and personalized where possible to suit the genre and purpose of the analysis. Analysis is ongoing research for all of us and only by listening and questioning will we learn more about our craft.

We have provided another four listening analyses for you to look at. Try and listen to these tracks and see if you concur with the analysts views. Let’s listen!

As we’ve discussed, each producer will have a watermark or range of watermarks for types of material. It is important to note that the watermark can work in two ways. It can be a statement, or sonic identity, of a particular producer’s style. Or it can be an application of certain tools for a desired outcome.

Some producers will have a distinct, intrinsic, natural style. It could be argued that Phil Spector is one of these. His wall of sound became one of the most notable watermarks in production history. Not only is it permanently linked with Spector, it is also simply the most famous producer’s watermark, often imitated. Not every producer has the benefit (or disadvantage) of such a distinctive watermark. Too distinctive a watermark can equate to pigeonholing, which might lead to being branded for certain limited styles of music or artist. Having no watermark can leave the producer indistinct and unable to stand out from the crowd.

We talk in this book about watermarks being a sonic musical outcome; however, a watermark can equally be a reflection of your professional reputation. Long-standing successful producers such as Trevor Horn continue to enjoy great success producing a variety of styles of music. He is seen within the industry as not only a pioneer of music production but also as a “safe” pair of hands to insure a relative amount of success from a project. Horn has continued to develop a reliable team of professionals at the top of their game alongside his wife Jill Sinclair to develop contributory projects such as ZTT, Sarm Studios, which all feed back to support his production work. We also talk in this book about being a business, as this can become equally important as the toolkit that defines your sonic style discussed in this chapter.