7

Fair and Legitimate Process

"It is easier to make certain things legal than to make them legitimate."

—Sebastien-Roch Chamfort, French playwright

Mark Ager's firm had designed a software application that was earning rave reviews from its primary customer. The U.S. military employed the company's innovative expert diagnostic system for the control, maintenance, and repair of sophisticated weaponry. In the late 1990s, the company's engineers and programmers discovered, quite opportunistically, that a firm in the automobile industry had an interest in this software application. The company soon landed a lucrative contract with its first major nondefense customer. The technical staff worked feverishly to adapt the software to meet this client's needs, and they began to grow excited about the possibility of finding customers who could use the technology in a wide range of nonmilitary applications. As head of business development, Ager believed that the firm did not have the marketing and distribution capability required to commercialize the technology successfully. In his view, the company needed a strategic partner. He set out to find the perfect match. Moreover, he began to sell his colleagues on the concept of an alliance or joint venture.

Moving quickly, Ager identified several software firms offering similar types of products, and he initiated informal conversations with members of each organization. He consulted a few colleagues about the potential partners, but he chose to "play it close to the vest" until he learned more about each firm and come to some conclusions. Before long, he focused his attention on a rapidly growing company recognized for its strong national sales organization and a product line that appeared to complement his firm's new expert diagnostic system. At this point, he began to work closely with a fellow executive who maintained responsibility for the software product's development and financial performance. After more discussions with the potential alliance partner, Ager's intuition told him that he had found a good fit; his colleague agreed wholeheartedly. Now, they had to bring all their colleagues on board.

It took much longer than Ager expected to build consensus among senior managers, and he encountered substantial obstacles along the way. Why did he find it so time-consuming and challenging to achieve buy-in for his proposal? Interestingly, very few colleagues reported serious misgivings about his recommendation; they did have concerns about how he had managed the decision process. One executive said:

As champion, he sold it. He sold the concept that we had to have an alliance or a partnership. Once the process started, it was relatively secretive. I knew it was going on. If I asked some pointed questions, I'd get some answers, but there were no briefings, there was no discussion, there was no passing a document around for view, anything of that sort.

This manager's feelings reflect the concerns expressed by many of Ager's colleagues. They thought that he had not managed an open and transparent process in which people with diverse perspectives, interests, and expertise had an opportunity to influence the final decision. Some managers indicated that they felt the choice was "preordained" by the time they had an opportunity to weigh in with their opinions. This dissatisfaction with the nature of the decision-making process impeded the development of commitment to the proposed course of action. Ager's troubles demonstrate an important lesson for all managers. Individuals do not care only about the outcome of a decision; they care about the nature of the process as well. Specifically, if members of an organization perceive a decision process as unfair and illegitimate, they are far less likely to commit to the chosen course of action, even if they agree with many aspects of the plan itself. This chapter explores the meaning of procedural fairness and legitimacy, and examines how these two process attributes form the building blocks of management consensus and pave the way for a smooth implementation effort.

Many leaders do not think in these terms when they try to build consensus and achieve closure in their firms. Naturally, they believe that consensus building on complex issues requires a healthy dose of persuasion coupled with the ability to negotiate compromises among senior executives whose interests sometimes clash.1 Yet, building commitment and shared understanding begins with the construction of a solid foundation to the decision-making process; a leader tills the soil so that it is fertile for consensus building by creating processes that are fair and legitimate. Only then can leaders apply their persuasion and negotiation capabilities to craft decisions with strong buy-in from all key parties in the organization. Through it all, of course, leaders need to manage conflict effectively, so that interpersonal friction and personality clashes do not erode the development of commitment and impede the firm's ability to implement its plans.

Fair Process

During a decision-making process, some individuals will have their views accepted by the group, while other proposals garner little support. Advocates for each alternative hone their arguments, often believing that they must change others' minds to garner their commitment and cooperation during the implementation process. The presumption that one must alter the opinions of others to secure their buy-in to a plan proves to be false. Unanimity usually proves to be an elusive goal in a decision-making process. Not everyone will agree with the final choice, no matter how ardently advocates try to change the minds of their opponents. One may think that a lack of unanimity creates an obstacle to implementation. However, this absence of ultimate agreement may not be a problem, if everyone believes that the organization employed a fair and just process for arriving at a decision. People do not have to agree with a plan to support an organization's efforts to execute it. If individuals perceive the process of deliberation as fair, they are more likely to cooperate during implementation, even if they disagree with the chosen course of action. Naturally, leading a fair process does not guarantee commitment, but it raises the odds quite substantially.

Defining the Concept

What does it mean for a process to be fair? To answer this question, we begin by turning to an interesting stream of research in the field of law, which has subsequently had an enormous impact on those who study how decisions are made in business organizations. Scholars John Thibault and Laurens Walker first demonstrated that people engaged in a legal dispute do not care only about distributive justice (i.e., whether the outcome constituted a fair and equitable division of resources among the parties).2 Their work challenged the fundamental notion that people only cared about the extent to which they receive a favorable verdict in a legal proceeding. Thibault and Walker illustrated that a disputant's satisfaction with a verdict was "affected substantially by factors other than whether the individual in question has won or lost the dispute."3 In fact, the choice of procedure employed to resolve the legal dispute mattered a great deal. For instance, they showed that disputants cared a great deal about whether a particular procedure provided more or less opportunity for biases to affect the outcome.

Subsequent research by Tom Tyler and others showed that higher perceptions of procedural fairness tended to be associated with more favorable evaluations of the people and institutions involved in a legal proceeding as well as greater satisfaction with the entire court experience. Perhaps most interestingly, Tyler also demonstrated that the use of fair processes provides a "cushion of support" for authorities when they make a ruling that is objectively unfavorable for the individual involved.4 When unfair procedures were employed, individuals receiving a favorable verdict expressed much higher levels of satisfaction with their legal experience. However, with fair procedures, people receiving an unfavorable verdict expressed a level of satisfaction much closer to the satisfaction levels of those who secured a favorable outcome! Other studies have confirmed this "cushion of support" effect provided by fair legal processes. Figure 7-1 shows the result from one such study by Adler, Hensler, and Nelson in 1983.

Reprinted with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Lind and Tyler. (1988). The Psychology of Procedural Justice. Figure 4.3.

Figure 7-1. Procedural fairness and the "cushion of support"

How do these findings in the field of law inform our understanding of how business leaders can build consensus when making critical choices in their firms? It turns out that individuals care a great deal about the perceived fairness of organizational decision-making processes, just as they care about the fairness of legal proceedings. Some managers equate fairness with "voice"—i.e., giving everyone a chance to air his views and ideas. Yet, procedural justice entails more than just allowing people to express their opinions openly and candidly. People want to feel that they have been heard when they have spoken, and they desire a real opportunity to affect the decisions made by their leaders.5 They do not want to feel as though their leaders have engaged in what my colleague Michael Watkins refers to as a "charade of consultation"—a process steered by the leader to arrive at a preordained outcome (see Figure 7-2).

Figure 7-2. The "charade of consultation"

Specifically, individuals tend to perceive decision processes as fair if they

- Have ample opportunity to express their views, and to discuss how and why they disagree with other group members.

- Feel that that decision-making process has been transparent (i.e., the deliberations have been relatively free of secretive, behind-the-scenes maneuvering).

- Believe that the leader listened carefully to them and considered their views thoughtfully and seriously before making a decision.

- Perceive that they had a genuine opportunity to influence the leader's final decision.

- Have a clear understanding of the rationale for the final decision.6

Leading Fair Processes

What can leaders do to enhance the perceived fairness of a decision-making process? The answer is simple to articulate, yet frustratingly difficult to execute at times—they must demonstrate authentic consideration of others' views. That is, leaders have to show that they have paid close attention to the proposals put forth by their colleagues and advisers, and that they have contemplated and evaluated those views seriously and genuinely before choosing a course of action. In a fascinating experimental study, Audrey Korsgaard, David Schweiger, and Harry Sapienza showed that "the manner in which team leaders elicit, receive, and respond to team members' input affects their attitudes toward the decisions themselves and toward other members of teams, including the leaders."7 In short, demonstrating consideration for others' views enhanced perceptions of fairness, commitment to the final decision, attachment to the group, and trust in the leader (see Figure 7-3).

Figure 7-3. The effects of consideration

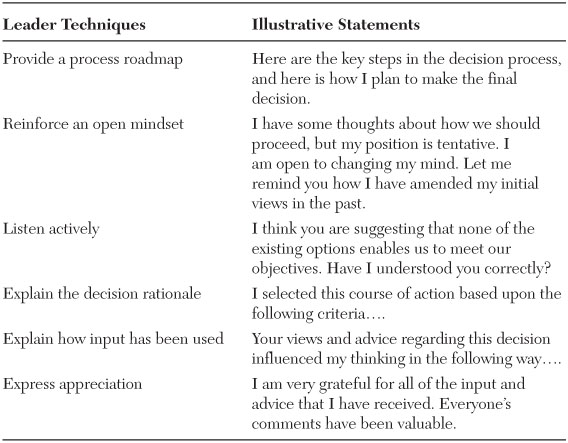

Leaders can employ a number of techniques to ensure that others conclude that their views have been considered in a genuine manner (see Table 7-1). To begin with, a leader should make a concerted effort to provide a clear process roadmap, meaning that he describes how the decision process will unfold.8 He explains the key steps in the process, the role that he will play in the discussion, and the manner in which he expects team members to contribute to the dialogue. The leader also makes it very clear how the final decision will be made (i.e., at what point and in what manner he will bring the discussion to a close and select a course of action). The theory is simple—no surprises!

Table 7-1. Demonstrating Consideration

For instance, if one wanted to employ a Dialectical Inquiry approach to decision making, he should explain that the team will split into subgroups, generate alternatives, and then critique each other's proposals. He might even provide a bit of guidance as to how the subgroups should present their proposals to one another (i.e., written versus oral form, explicit statement of assumptions, clear documentation of supporting evidence, etc.) The leader would then goon to explain how he intended to interact with the subgroups, and perhaps state that he planned to make the decision after hearing a final debate between the subgroups. Naturally, a leader must remain flexible, and be willing to alter this process roadmap as deliberations unfold and unexpected twists and turns arise. Clearly, however, one must remember to communicate clearly how and why the original roadmap will be revised due to changing conditions.

Having established a vision of how the process will unfold, a leader must be proactive about countering the impression that the decision has already been made. He must ensure that others do not conclude that he simply wants to create the appearance of a consultative decision process. In many organizations, individuals have grown accustomed to "sham" decision processes. In those cases especially, leaders need to combat that deep-seated cynicism before moving forward. Some leaders accomplish that by choosing not to state their views at the start of the decision process, and by declaring that they need to hear everyone's thoughts and ideas before formulating an opinion on the matter at hand. Others may express an initial position on the issues, but make it very clear that they are open to changing their minds. A leader might even cite an instance in the recent past, when consultation with others had led to a complete reversal or significant adjustment in his views.9

After deliberations begin, leaders can demonstrate consideration by engaging in active listening, rather than sitting rather passively as people present ideas and proposals. Active listening shows that the leader is paying close attention to each speaker, and is trying hard to develop a thorough and accurate understanding of each person's views. When leaders engage in active listening, they ask questions for clarification or further explanation, test for understanding, and avoid interrupting people as they express their ideas. They take detailed notes as each person speaks, and they "playback" what they hear—that is, the leader summarizes each person's comments and asks the individual if that re-statement represents an accurate description of his proposal. Finally, leaders need to provide individuals with an opportunity to restate their recommendations if they believe that they have been misunderstood.10 To evaluate your own listening skills, consider the questions shown in Table 7-2. If you answer "yes" to most of those questions, make a commitment to improving your capability to listen actively and effectively.11

Table 7-2. Do You Listen Effectively?

Some leaders may believe that demonstrations of consideration end when deliberations are complete and they have chosen a course of action. That presumption proves to be false. Specifically, leaders tend to enhance perceptions of procedural fairness if they explain the rationale for their decision after it has been made. An effective explanation typically outlines the criteria employed to evaluate various alternatives and select a course of action. The leader also should explain how he incorporated each person's input into the final decision, as well as why he may have chosen not to take someone's advice. Individuals want to know how they contributed to the final outcome, and often, they even desire an explanation for why the leader has chosen not to heed key aspects of their advice.12

Finally, leaders enhance perceptions of fairness if they express appreciation for the input that they have received before announcing their choice. As they speak to their teams, leaders should note that, although they value all ideas, they may choose not to adopt the recommendations presented to them during the decision-making process. For instance, Andrew Grove, former CEO of Intel, made it clear to his managers that he valued their input, and would try to listen and understand, although he might not heed their advice in all cases. Grove recalled telling his troops: "Give your considered opinion and give it clearly and forcefully. Your criterion for involvement should be that you're heard and understood. Clearly, all sides cannot prevail in the debate, but all opinions have value in shaping the right answer."

As Mark Ager tried to persuade his colleagues that his firm should pursue an alliance with a software provider that he considered a perfect fit, he did not consider others' perceptions of procedural fairness. Having made up his mind by the time he consulted with many key parties, he had a difficult time overcoming the belief that he was driving the process to the conclusion that he desired. Although he asked for people's thoughts and opinions and may very well have wanted to hear their input, most individuals wondered whether they could affect the outcome of the decision process. Don Barrett faced a similar problem at All-Star Sports. When he asked his entire senior management team to ratify decisions he had arrived at with a small subgroup of advisors, many executives felt that it was too late to have a genuine opportunity to influence the final decision. Dismayed by the lack of transparency and the feeling that they could not reverse the decision at that point, they often did not speak their minds and raise objections during the staff meetings.

Fair Process in Action

When Paul Levy arrived at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, prior management often had presented plans to the staff without building a sense of collective ownership. People often felt that plans came down from on high as fait accompli. The chiefs (the physicians who led each department in the hospital) often became frustrated because they did not believe that management listened and considered their views. Levy went to great lengths to change the atmosphere and ensure that people had an opportunity to voice their opinions on major policy issues, and then he demonstrated consideration for their views while always making it very clear that he would make the final call. Before he took the job, a consulting firm had conducted an extensive study of the problems at the hospital, but they had not yet released their findings. In his very first week at the hospital, he posted the consulting firm's recommendations on the organization's intranet and asked for feedback. He responded personally to more than 300 e-mails from staff members. One month later, as Levy announced his plan for turning around the hospital, he explained why he had accepted some of the recommendations made by the consultants, but not others, and he explicated precisely how he had utilized the feedback that he had received from people throughout the hospital. People knew the rationale for his decisions, and they could see how their ideas had shaped and influenced his thinking. Because of higher perceptions of procedural fairness, most individuals respected the fact that he had rejected some of their advice. Once again, he posted his turnaround plan on the intranet. This time, he asked everyone to "sign" the plan, solidifying the sense of collective ownership and commitment to the new strategy.

After putting forth his strategic plan, Levy established a series of task forces to develop specific plans for how to achieve the goals that he had outlined. As he created the task forces, Levy made it clear how he expected the decision-making process to unfold. In short, he laid out a process roadmap and secured everyone's commitment to the process, long before anyone knew what recommendations the committees would develop. Specifically, Levy provided a broad outline of how the task forces would do their work—how they were to analyze how to improve certain areas of the hospital, as well as the role that he and the department chiefs would play in the final decision-making process. Levy did not want the chiefs to meddle in the work of each committee, leading once again to a pattern of indecision and action. He gave the task forces the freedom to collect data, evaluate options, and develop recommendations. Then, he expected the chiefs to assess the proposals put forth by each task force, and to offer him input and advice. Levy promised not to execute any major recommendations without consulting the chiefs. However, he retained the right to make the final decision if the chiefs could not come to an agreement. Levy made it clear that people had to voice their objections openly when he asked for advice, rather than staying silent and working behind the scenes to undermine key decisions as they had in the past. Because he created stronger perceptions of procedural fairness, individuals started to become much more comfortable expressing their views openly during staff meetings. The "culture of yes" began to change.

Note that Levy did not institute a democracy at the BIDMC. Far from it, indeed! He made tough decisions to cut costs, reduce headcount, and restructure operations—often making choices that went counter to the wishes of his staff. Despite his tough measures and decisive actions, he built commitment and shared understanding for his turnaround plan because people believed that he had operated in a just and transparent manner.

Some leaders may believe that fair process works fine without time constraints, but that the need for speed and efficiency precludes demonstrating consideration in times of crisis. This line of reasoning proves incorrect. Consider NASA's Apollo 13 mission to the moon in April 1970, in which an oxygen tank explosion aboard the spacecraft nearly led to catastrophe. Flight Director Gene Kranz led a remarkable creative effort to engineer a solution that would enable the astronauts to return to Earth safely.13 He asked his team for unvarnished advice, and he listened carefully as technical experts debated multiple options for bringing the crew home. People trusted Kranz because he asked lots of questions, pushed for clarification when people made their arguments, tested for understanding, and demonstrated repeatedly that he could acknowledge when his initial thinking was incorrect. Kranz described the decision-making process:

I used the same brainstorming techniques used in mission rules or training debriefings, thinking out loud so that everyone understood the options, alternatives, risks, and uncertainties of every path. The controllers, engineers, and support team chipped in, correcting me, bringing up new alternatives, and challenging my intended direction. This approach had been perfected over years, but it had to be disciplined, not a free-for-all. The lead controllers and I acted as moderators, sometimes brusquely terminating discussions...With a team working in this fashion, not concerned with voicing their opinions freely and without worrying about hurting anyone's feelings, we saved time [emphasis added]. Everyone became part of the solution.14

Note that Kranz remained firmly in control, and he made tough, rapid decisions that often required him to reject the advice and input of very capable subordinates. Yet, people trusted him completely and dedicated themselves completely to the execution of his decisions. Their trust came, in part, from their admiration of his technical expertise; but, his leadership of the brainstorming process and his strong listening skills affirmed and enhanced that trust. Moreover, he found that leading a fair process "saved time" rather than causing costly delays, because he could quickly gather information and advice from a wide variety of sources.

Legitimate Process

When Jurgen Schrempp took over as CEO of Daimler Benz, he discovered that the company had become incredibly bureaucratic; division heads ran their units as independent fiefdoms, and many businesses did not earn an adequate return on capital employed. He sought to restructure the organization and streamline its complicated governance structure. He also wanted to assert control over the "feudal lords" that led key units. In particular, Schrempp decided to assert control over the highly independent Mercedes subsidiary. He wanted to fold Mercedes into Daimler, thereby eliminating the subsidiary's fiercely independent CEO and management board and reducing extensive duplication of functions between the corporate office and headquarters of the business unit. Yet, Schrempp did not just make the decision to restructure the organization. Instead, he asked a key lieutenant to develop eight alternatives for reorganizing the corporate governance structure, and all the while steering the discussion toward his preferred solution. Bill Vlasic and Bradley Stertz, authors of an insightful book that chronicled the events leading up to the Daimler-Chrysler merger, explained how the decision-making process unfolded:

Schrempp, the canny chess player, didn't want to bring his chosen solution to Daimler's management and supervisory boards as the only alternative. No, there must be a variety of choices to stimulate discussion, allow the board members to be part of the process, and dispel any notion that Schrempp was forcing it down their throats...[The management team] debated the various options. Schrempp always came back to Model Number Six, which merged Mercedes into Daimler and abolished the position of the Mercedes CEO.15

Why did Schrempp present so many alternatives if he had already made up his mind? Why did he believe that he had something to gain by outlining eight alternatives? Schrempp clearly had a method to his madness; he had carefully thought through his strategy for leading the decision-making process. He believed that presenting multiple options provided a key benefit to him. However, in cases such as this one, managers often recognize how a leader has manipulated the decision process. That recognition shapes their perceptions moving forward, and it may imperil the implementation of future choices. In fact, Schrempp used this style of decision making again during the Chrysler merger deliberations, and in part, that may explain why the organization encountered such difficulties during the integration process.16

What Is Procedural Legitimacy?

The Daimler example highlights how efforts to enhance procedural legitimacy affect the development of consensus in organizations. What do we mean by procedural legitimacy? Organizational sociologists define the concept as the perception that organizational processes and techniques are "desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions."17 That may seem like a mouthful, but the concept is rather simple. People come to believe that there is a "right way" to do certain things in organizations, and they are more accepting of outcomes if the process that they observe conforms to that "right way."

How do concerns about procedural legitimacy affect decision making in firms? Scholars Martha Feldman and James March once observed that "organizations systematically gather more information than they use, yet continue to ask for more."18 They argued that firms employ information for its symbolic value, as well as for its effect on the quality of a decision. Gathering extensive amounts of information symbolizes that managers are engaging in a comprehensive and analytical decision-making process. Feldman and March suggest that social norms and values emphasize the merits of rational, or comprehensive, decision making. Thus, gathering extensive amounts of data legitimizes a decision process. Put another way, people feel more confident in the decision itself, because they recognize that the process was conducted in the "right way"—i.e., in a highly analytical, data-driven manner. Individuals will not commit to a decision if they believe the process was irrational, incomplete, or just plain sloppy. As Feldman and March argued, "Using information, asking for information, and justifying decisions in terms of information have all come to be significant ways in which we symbolize that the process is legitimate."19

Other actions may symbolize rational choice, and thereby bolster procedural legitimacy. In particular, the generation of multiple alternatives and the utilization of formal analytical techniques (such as a discounted cash flow model or psychometric market research study) also signify that managers are employing a thorough and logical decision-making process.20 Thus, Schrempp may have put forth eight options, because he knew that others expected to see an extensive analysis of alternatives for any major strategic choice. He recognized that board members would not accept and support a recommendation that lacked a comparative analysis of multiple options, even if the content of the recommended plan of action seemed sensible and feasible.

Managers hire external consultants to convey a sense of process legitimacy as well. To be sure, many readers have experienced this phenomenon. A firm's executives know what course of action they would like to take, but the use of well-known consultancies with highly respected reputations provides a "stamp of approval" for their plans. The consultants apply a series of analytical frameworks to justify the course of action that executives would like to undertake. The confirmation from a credible outside source, backed by formal analysis, helps to solidify internal support for a decision, and it protects managers from the potential charge that they did not think through the issue thoroughly before taking action.

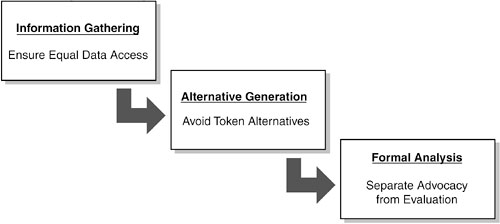

Destroying Legitimacy

Unfortunately, efforts to enhance process legitimacy may not always produce the desired effect. Scholars Blake Ashforth and Barrie Gibbs point out that, in some cases, constituents may perceive attempts to legitimate processes as "manipulative and illegitimate."21 Indeed, the findings of my research suggest that symbolic activity undertaken during the decision-making process may backfire, decreasing legitimacy and diminishing the formation of consensus.22 For example, individuals may present a list of alternatives for purely symbolic reasons, rather than because they want to generate an authentic debate and consideration of those options. Others may perceive these proposals as "token alternatives"—think of seven of the eight possible restructuring plans outlined by Schrempp and his lieutenant—and conclude that individuals are attempting to manipulate the decision-making process. Similarly, someone may present a discounted cash flow model because executives within that firm typically value such structured techniques for evaluating capital investments, but the results may be skewed to justify a particular proposal rather than to evaluate multiple options equitably. If so, these attempts to enhance procedural legitimacy and persuade others to support a particular proposal actually will delegitimize the process and reduce management buy-in.

Leaders must remember that individuals make critical attributions during decision-making processes. They attribute motives to others' actions.23 They may perceive extensive information gathering, alternative generation, and the use of formal analytical techniques as authentic efforts intended to enhance the quality of the decision. On the other hand, they may believe that others are trying to manipulate, "rig," or preordain the process. If individuals perceive self-serving motives on the part of others, they become disenchanted with the decision process, and that disillusionment hinders the leader's ability to build consensus and achieve closure.

Just as leaders need to evaluate how their own actions affect perceptions of legitimacy, they also must monitor the legitimacy of others' actions. Ardent advocates of a proposal, such as Mark Ager, will strive for process legitimacy as they try to sell their ideas to superiors, peers, and subordinates. However, they can do more harm than good if the leader does not recognize and address the problem quickly.

Consider again Mark Ager's efforts to persuade others to support his alliance proposal. He offered a number of "token alternatives" during the decision process. A token alternative is a proposal that draws a significant amount of discussion and analysis, but is not ever considered seriously. A token alternative differs in an important way from a "straw man"—which has a great deal of value in a decision process. With a straw man, people understand that it will never be implemented, but they recognize the value of discussing it as a means of testing assumptions and stimulating critical thinking about a complex issue. In the case of token alternatives, people present options purely for symbolic reasons, rather than for their substantive value. Upon reflection, Ager recognized that he had offered token alternatives to the management team:

We did some internal analysis about who were the software tool providers that we should team with. We had a chart that said that what we ought to do is team with a tool provider. And we had a bunch of alternatives listed. And to be honest with you, between Bill and I—it was kind of a half-assed attempt, because we knew we wanted to go with ZTech. But, we were filling in the required work that said: Would you go with Jet Corp.? No, why not? Would you go with Keystone? No, why not? So, we had that list.

The quote implies that Ager felt compelled to offer multiple options to make the process appear thorough and analytical, and to conform to the "standard way" in which people expected such decisions to be made at the firm. However, others understood the game being played. They perceived these efforts as manipulative. One executive noted, "I don't think we looked at anybody seriously except for ZTech." Another explained, "This was pretty ordained from the first day. They knew they were going to do this, and this six months of...this has just been goofing around."

Token alternatives appear to be a rather common feature of many firm's decision processes, and they typically do not fly under the radar—people recognize the self-serving behavior in most cases, and the leader often finds that the decision process grinds to a halt as procedural legitimacy collapses.

A similar phenomenon takes place with regard to information gathering in many organizations. Individuals naturally want to use data to support their arguments, justify assumptions, and persuade others to endorse their proposals. Often, they present extensive amounts of data to convince others that they have done a thorough investigation of the issues at hand. However, my research suggests that individuals employ two different approaches to disseminating that information prior to critical meetings. In some cases, managers provide each attendee with all available information prior to key deliberations. In other instances, managers provide some colleagues with more information than others. In many cases, this phenomenon occurs because individuals try to "pre-sell" a few key executives on the merits of their proposals prior to meetings, and to build a coalition that will support them during the group deliberations. To persuade these influential executives, individuals provide them with preferential access to key data prior to group discussions.

The failure to disseminate information to all participants prior to key meetings typically harms process legitimacy, rather than enhancing it. People feel disadvantaged if they are examining data for the first time, while others have reviewed it earlier. Individuals question whether their views and opinions are truly valued, if others have failed to share information with them. In addition, participants wonder whether they can influence the opinions of those with privileged access to data, or whether these individuals have established strong, unalterable preconceived notions.

An organizational restructuring decision at Ager's firm illustrates the problem caused by unequal dissemination of information. One executive shared data about various alternatives with only a few other staff members prior to a major offsite meeting. When he did provide extensive data to the entire group, individuals were not impressed by the thoroughness of the intelligence gathering effort, but instead, felt as though he was presenting them with a fait accompli. The vice president of engineering explained what happened at the start of the offsite meeting:

We had an offsite meeting, and Dave tried to show the team that he had investigated all the options carefully. Ron and I were the only people besides Dave who had examined the data at that point. It became apparent very quickly to the rest of the staff, after they didn't see me shrink like a violet in my chair, that I had seen the data already. So I'm a bad guy right away...I don't think that this decision was preordained, but that's what many people believed during and after that discussion, even to this day.

Preserving Process Legitimacy

How, then, do leaders preserve the legitimacy of a decision-making process? They cannot eliminate symbolic behavior—at times, it has great value in organizations. People always will evaluate decision processes against a set of societal and organizational values and norms regarding what constitute the "right ways" to make complex choices.24 Thus, individuals have an inherent incentive to signal that they have gathered extensive data, examined an exhaustive list of options, and employed favorite analytical methods.

Recognizing that fact, leaders still can take steps to ensure that symbolic behavior does not become a road block to consensus (see Figure 7-4). First, leaders must ensure that all participants in a decision process have equal access to information, to the greatest extent possible. If they want to build commitment, leaders need to create a level playing field before initiating a debate among their advisers and subordinates.

Figure 7-4. Principles for preserving process legitimacy

Second, leaders can test for the presence of token alternatives, and then either take them off the table or force serious consideration of those proposals. They might have to push their teams to invent new options that do warrant genuine consideration. Moreover, leaders ought to distinguish clearly between a "straw man" being used to push critical divergent thinking and a token alternative being used in a manipulative manner.

Finally, leaders should strive to separate advocacy from evaluation. Recall the Kennedy handling of the Bay of Pigs decision. Presidential adviser Arthur Schlesinger states that the CIA presented "a proposal on which they had personally worked for a long time and in which their organization had a heavy vested interest. This cast them in the role less of analysts, than of advocates."25 As political scientist Alexander George points out, flawed reasoning can go untested "when the key assumptions and premises of a plan have been evaluated only by the advocates of that option."26 Interestingly, my research suggests that separating advocacy from evaluation does not only enhance the quality of decisions, but it also tends to enhance process legitimacy and management consensus. To separate advocacy from evaluation, leaders can ask multiple units of the organization to conduct independent evaluations of the proposals under consideration, as Kennedy did during the Cuban missile crisis. In some situations, leaders might even invite third parties—unbiased experts of some kind—to provide objective analysis of the alternatives put forth by various advocates within the organization.

The Misalignment Problem

Leaders face one additional challenge when trying to foster procedural fairness and legitimacy. Simply put, many leaders have a hard time detecting whether a group perceives a decision process in the same way that they do. For example, when I surveyed Don Barrett and his management team at All-Star Sports, the results proved quite enlightening. On a series of questions that asked individuals to rate the management team's effectiveness, Barrett consistently reported much higher scores than the average of all other team members.27 Barrett's case is not unique. Similar misalignment often occurs with regard to perceptions of procedural fairness and legitimacy. On many occasions, a leader believes that he has managed a decision process in a just and legitimate manner, but his advisers and subordinates find that he has not demonstrated sufficient consideration, or they detect the presence of token alternatives. If a leader proceeds under a false impression of the team's satisfaction with the decision process, he may find himself surprised when implementation goes astray amidst a lack of management buy-in.28

How then can leaders test to make sure that their team's perceptions of the process match their own? One can begin by making it a habit to conduct "process checks" from time to time as a decision unfolds. Management teams should practice auditing their decision-making processes, with particular attention paid to their ability to generate dissent, manage conflict constructively, and maintain fairness and legitimacy. These audits need not wait until a process has ended and a decision has been made; teams can perform quick assessments in real-time to ensure that a process is on track.

Second, leaders can take individuals aside and hold one-on-one meetings to test for alignment. Some individuals may be more comfortable expressing their concerns about a decision process in a private setting, rather than doing so amidst a group discussion.

Third, the leader can absent himself from a group meeting and ask members to discuss their concerns about the team's approach to decision making among themselves. In the leader's absence, people will feel more open to divulge their reservations about, for example, the extent to which a leader listens attentively and demonstrates genuine consideration for others' views.

Finally, a leader must pay close attention to body language and other nonverbal cues during meetings and other interactions with advisers and subordinates. People often express dissatisfaction or reservations about a decision process through facial expressions, gestures, or changes in their posture. If leaders observe troublesome cues such as these, they need to find time, perhaps outside of a group meeting, to question the individual about their perceptions of the decision process. They may have concerns about the content of that particular decision. In that case, by pulling them aside, the leader can uncover critical dissenting views that had not emerged. At times, though, the leader may discover that the nonverbal cues point to process concerns rather than disagreement pertaining to the subject matter being examined and discussed.

Teaching Good Process

Leadership requires more than just the personal practice of good process to build consensus and achieve closure. Leaders must teach effective process to the members of their team as well. After all, the entire team benefits when all members, not just the leader, learn active listening techniques and begin to demonstrate greater authentic consideration of others' views. Preserving the legitimacy of a decision process requires teamwork, too. The leader may present preordained decisions from time to time, compromising process legitimacy and management consensus. However, team members often damage process legitimacy through their vigorous advocacy of pet projects and proposals. Sound process leadership requires more than a policing or monitoring capability; it means educating all team members regarding how to elevate the fairness and legitimacy of the group decision process. By teaching good process, leaders also enhance the likelihood that decision making will improve at all levels of an organization. Of course, teaching is not always easy—sometimes, it requires the delivery of negative feedback and the willingness to instill discipline.29

At the Beth Israel Deaconess, Paul Levy set out to tackle the curious inability to decide, and to build more collective ownership around key decisions. He knew that decision making needed to change at all levels, not just within the executive suite. By practicing some of the principles of fair process, he began to encourage people to stop remaining silent during group discussions, and then undermining, objecting, and obstructing plans later after an apparent consensus had been reached (classic indications of the culture of yes that had developed over the years). He tried to teach good process to people at all levels by establishing new norms, modeling desired behaviors, and giving people an opportunity to practice approaches to decision making that were both fairer and more disciplined.

Not everyone got the message. In Levy's second month on the job, he discussed an important issue with his staff, and by the end of the meeting, he thought that the group had reached consensus on how to proceed. He reminded everyone of his efforts to combat the "culture of yes" and asked whether everyone truly supported the decision. No one expressed objections or concerns. Just a few days later, one chief complained publicly about the decision, despite having remained silent in the staff meeting. Levy chose to reprimand the individual publicly, pointing out that he had been given numerous opportunities to voice his ideas and concerns in a constructive manner. Of course, public criticism can be dangerous, but in this case, Levy employed it judiciously to reinforce the new behavioral norms. It became a teaching moment, not just for that individual but for the entire management team.

Levy also delegated many tactical decisions and responsibilities, providing managers at all levels the opportunity to practice new approaches to problem solving and decision making. He took on the job of monitoring the way that people went about making those decisions to ensure that people embraced the new norms and employed them effectively to achieve consensus and reach closure in a timely manner. However, he did not micromanage. As groups went about their work, Levy chose to think of himself as the organization's version of an appeals court judge. He did not want to review all cases de novo (starting all over) and simply overrule decisions made by the lower court; instead, he strove to "review the decision process used by the lower court to determine if it followed the rules."30 If so, its decision often stood. If not, he intervened to teach his managers how to lead more effective decision-making processes. He did not simply correct their choice.31

What About Conflict?

This chapter focused on building consensus. Some might wonder what happened to all the talk about conflict, dissent, and divergent thinking. How does one reconcile this discussion of fairness and legitimacy with earlier descriptions of how leaders can stimulate the clash of ideas? The answer is actually rather simple. Let's go back to our definition of consensus. It does not equal unanimity or even majority rule. It does not mean that teams, rather than leaders, make decisions. It does not mean that one must find a compromise solution that marries elements of multiple options. Consensus means that people comprehend the final decision, have committed themselves to executing the chosen course of action, feel a sense of collective ownership about the plan, and are willing to cooperate with others during the implementation effort.

Leaders can and should build consensus even when team members cannot reach unanimous agreement on a complicated issue. In fact, too much unanimity ought to be a warning sign that people might feel unsafe expressing their views. Striving for consensus certainly does not mean minimizing conflict among the members of your management team. In fact, to build a strong and enduring consensus, leaders need to stimulate conflict, not avoid it.

Although that last statement may sound counterintuitive, think about the concepts of procedural fairness and legitimacy again. The opportunity to engage in vigorous debate plays a critical role in shaping perceptions of fairness and legitimacy. Individuals will not perceive a decision process to be fair if they have not had an opportunity to air their diverse points of view, and to disagree with one another—and the leader—openly and candidly. People do not consider a process to be legitimate if they are steered toward a preferred solution or presented with token alternatives; they want the opportunity to debate a genuine set of options on an equal playing field with their colleagues. Scholars W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne try to dispel the notion that one must avoid conflict to build commitment and foster active cooperation:

Fair process does not set out to achieve harmony or to win people's support through compromises that accommodate every individual's opinions, needs, or interests... Nor is fair process the same as democracy in the workplace. Achieving fair process does not mean that managers forfeit their prerogative to make decisions.32

Those final words remind us that, when all is said and done, people need to be led if an organization is to move forward. Not everyone will agree with the decisions that a leader makes. Yet, we have learned that people care about process, not simply the outcome or verdict. By creating fair and legitimate processes, leaders can create the "cushion of support" that enables them to make tough decisions, about which reasonable people will disagree. As leaders make difficult calls, they will have to step in to bring lively and argumentative decision processes to a close. In those instances, they need only remember the words an observant manager once shared with me: "People just want their positions heard. Then, they really want a choice to be made."