8

Reaching Closure

"Nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs."

—Henry Ford

During World War II, General Dwight Eisenhower commanded one of the most powerful military forces ever assembled in human history. Under his skilled leadership, the Allied Forces stormed the beaches of France, defeated Hitler's army, and liberated Europe. Several years later, the American people elected the popular war hero as their president. Naturally, not everyone believed that the retired general would make a smooth transition to the Oval Office. During Harry Truman's final months in the White House, he reflected on the challenges awaiting his successor: "He'll sit here, and he'll say, 'Do this! Do that!' And nothing will happen. Poor Ike—it won't be a bit like the army. He'll find it very frustrating."1

Truman spoke from experience. Getting his ideas and decisions implemented had been a formidable challenge at times. The obstacles did not always prove to be his opponents in Congress; at times, Truman encountered resistance from members of his own administration.2 Political scientist Richard Neustadt, who worked for Truman and several other chief executives, once observed, "The president of the United States has an extraordinary range of formal powers... despite his 'powers,' he does not obtain results by giving orders—or not, at any rate, merely by giving orders."3 Even the leader of the free world needs to build commitment and shared understanding if he wants his decisions to be executed in a timely and efficient manner.

As it turns out, Eisenhower could not simply issue dictums from on high, even as supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in World War II.4 He needed to hold a complicated alliance together and balance the competing demands of many strong-willed individuals on both sides of the Atlantic, including the two heads of state, Churchill and Roosevelt; each nation's military chief of staff, Marshall and Brooke; and powerful field commanders such as Montgomery, Patton, Tedder, and Spaatz. Historian Stephen Ambrose has pointed out that Eisenhower's diplomatic skills often proved to be more important than his strategy-making prowess. He observed:

Although none of his immediate superiors or subordinates seemed to realize it, Eisenhower could not afford to be a table-thumper. With Montgomery's prestige, power, and personality, for example, had Eisenhower stormed into his headquarters, banged his fist on the table, and shouted out a series of demands, his actions could have been disastrous.5

Eisenhower indeed proved adept at bringing people together and finding common ground. The enemy too recognized Eisenhower's strengths as a leader; the Germans once wrote that "his strongest point is said to be an ability for adjusting personalities to one another and smoothing over opposite viewpoints."6

Consider how Eisenhower chose the D-day invasion strategy amid much contentious debate among the heads of state and military commanders. He built commitment to the final plan by leading a fair and legitimate decision process. During often heated deliberations, Ambrose points out that Eisenhower "acted as chairman, listening judiciously to both sides, then making the final decision."7 He ensured that everyone "received a fair hearing."8 Moreover, "his basic method was to approach all problems objectively himself, and to convince others that he was objective."9

Eisenhower, however, did more than lead a fair process and make the final call when people could not reach agreement. He helped this group of incredibly powerful and strong-willed personalities reach closure on the D-day invasion strategy by breaking the complex issue down into manageable parts. Rather than settling on a strategy all at once, Eisenhower led a five-month process whereby the group gradually arrived at decisions regarding the date of the landings, the bombing strategy, the use of airborne troops, and whether to invade southern France at the same time as the cross-channel attack.

Eisenhower navigated contentious deliberations by seeking common ground whenever possible, often searching for agreement on key facts, assumptions, and decision criteria. According to Ambrose, when the commanders came together to debate whether to focus bombing on strategic targets within Germany or railway networks within France, Eisenhower ensured that the group "began by acknowledging those points on which everyone agreed."10 When they could not agree on a possible invasion of southern France, he sought agreement first on the level of resources required to prosecute the cross-channel attack effectively. After the group came to a conclusion on that point, it became much clearer to everyone that an invasion of southern France must be delayed—a point of view that Eisenhower had not endorsed initially.

Throughout the D-day deliberations, Eisenhower adopted a disciplined, step-by-step approach to securing commitment and reaching closure. He brought the group along gradually, building upon points of common ground. Although "Eisenhower's practice was to seek agreement,"11 he did make the tough call when all parties could not agree. Moreover, when he declared that matter closed and moved to the next area of debate, he did not allow people to revisit the matter and re-open it for further discussion.

Divergence and Convergence

Eisenhower's leadership in the months preceding the D-day invasion proves very instructive for those interested in understanding how to help a diverse group reach closure on a complex matter. In many ways, Eisenhower's approach challenges the conventional wisdom with regard to making complicated, high-stakes decisions.

Throughout this book, we have examined two pathologies that groups encounter as they try to make difficult decisions (see Figure 8-1). Some teams converge too quickly on a particular solution without sufficient levels of critical evaluation and debate. Others generate many alternatives, but cannot resolve conflict and achieve closure in a timely fashion.

Source: Adapted from J. Russo and P. Schoemaker. (1989). Decision Traps: The Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them. New York: Fireside. p. 153.

Figure 8-1. Two pathologies

To avoid these problems, scholars and consultants often argue that groups should try to encourage divergent thinking in the early stages of the decision process, and then shift to convergent thinking to pare down the options and select a course of action. This sequential divergence-convergence model, depicted in Figure 8-2, represents the conventional wisdom often espoused by those who are advising managers on how to make decisions more effectively.12 For instance, scholars J. Edward Russo and Paul Schoemaker make the following recommendation:

Source: Adapted from J. Russo and P. Schoemaker. (1989). Decision Traps: The Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them. New York: Fireside. p. 153.

Figure 8-2. The divergence-convergence model

For the vast majority of decisions, especially those of any import, the best process is at first expansive, with sufficient time for different opinions, converging on a final decision only after the group has considered the problem from many diverse perspectives.13

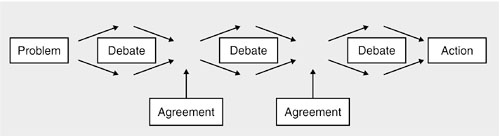

My research suggests that effective leaders direct an iterative process of divergence and convergence, much as Eisenhower did during the D-day deliberations (see Figure 8-3). Effective leaders do not encourage divergent thinking in the early stages of a decision process, and then turn their attention toward reaching closure and consensus in the latter stages of the deliberations. One does not achieve timely and sustainable closure by proceeding in this type of linear fashion Instead, leaders must actively seek common ground from time to time during the decision-making process. They cannot completely defer judgment on all issues while engaging in brainstorming, alternative generation, and debate, nor can they restrict convergent thinking to the latter stages of the decision process.14 They must reach intermediate agreements on particular elements of the decision at various points in the deliberations, lest they find themselves trying to bridge huge chasms between opposing camps late in a decision process.15

Figure 8-3. An iterative process of divergence and convergence

Like Eisenhower in the period before D-day, effective leaders treat closure as a process nurtured over time rather than an event that occurs at the culmination of an intense period of divergent thinking and debate. They do not seek commitment and closure in a single act of choice, but they strive for a series of "small wins"—concrete, intermediate points of agreement on elements of a problem—that bring factions together and build momentum toward a final decision.

To illustrate the power of an iterative process of divergence and convergence, consider a critical decision made by CEO Andrew Venton and his management team at a leading U.S. combat vehicle and armament manufacturer. In the late 1990s, the firm sought to compete for a joint British-American defense contract to design and build an advanced armored combat vehicle. Venton knew that he needed to put together an international joint venture, with several other leading American and British aerospace firms, to win this lucrative contract. It promised to be a complex decision with many unknowns and multiple points of contention among his staff members. For instance, much ambiguity existed about the precise customer requirements for the program, and no one expected the two nations to clarify those specifications for some time. Venton recognized, too, that his managers would have disparate assessments of potential partners because of their vastly different experiences working with firms on past projects.

This decision provides examples of the types of debates and intermediate agreements that can occur as an iterative process unfolds. As Table 8-1 illustrates, Venton and his team did not move sequentially from a divergent thinking mode to a convergence mode during their deliberations. In particular, note that convergent thinking took place at each major stage of the decision-making process.

Table 8-1. Profile of an Iterative Process16

Managers conducted a broad information search, examining the needs of the customers, as well as the capabilities of potential partners, on both sides of the Atlantic. They eventually agreed on the problem's magnitude and urgency as well as on the firm's objectives (i.e., how fast the program would come to fruition, how large it would become, and what type of team would be needed to win the contract). The decision makers generated many different alternatives, but then agreed on a feasible set of options as well as the criteria to be utilized to evaluate them. They debated the different alternatives, but periodically agreed to eliminate some of those options. For instance, managers came to the conclusion that their firm must find a company with more advanced systems-integration capability to lead the joint venture; therefore, all options with their firm as prime contractor were taken off the table. Finally, they made a choice, contingent upon specific events. Specifically, managers reached a tentative agreement that the best course of action would be to serve as a subcontractor in a joint venture with three other British and American firms. However, several managers had concerns about this choice. They would only support this decision if the firm could negotiate an adequate joint venture agreement, particularly with regard to the division of work on future contracts. Managers agreed to commence negotiations with the potential partners, only after agreeing among themselves on the specific conditions under which the firm should proceed with the alliance.

In sum, the managers iterated between periods of debate and instances in which they found common ground. Gradually, they tackled a highly complicated issue and arrived at a decision that everyone understood and to which everyone was highly committed. Moreover, this iterative process did not take an inordinate amount of time. It turned out to be one of the most efficient decision-making processes that I examined at the firm, both in terms of managers' internal evaluations of the process as well as my assessment as an outside observer.

The Psychology of Small Wins

Why is a "small wins" approach so effective when dealing with complex decisions? Modest agreements on a particular element of a problem bring new allies together, cause opponents to recognize their common interests, and consolidate and preserve progress that has been made during an intense set of deliberations. People begin to recognize that they can work constructively with one another despite their differences of opinion. One agreement serves as a catalyst for more productive debates and further agreements down the line. Psychologist Karl Weick explains:

By itself, one small win may seem unimportant. A series of small wins at small but significant tasks, however, reveals a pattern that may attract allies, deter opponents, and lower resistance to subsequent proposals. Small wins are controllable opportunities that produce visible results...Once a small win has been accomplished, forces are set in motion that favor another small win.17

A "small wins" approach helps groups overcome two types of obstacles that impede decision making in complicated, high-stakes situations. One obstacle is cognitive in nature, and the other is socio-emotional. First, complex problems can overwhelm groups due to the cognitive limitations, or what is known as bounded rationality, of the decision makers. To put it simply, individuals do not have supercomputers in their brains. They cannot process reams of information effectively; they must be selective. They cannot examine every possible alternative in a given situation, or think through the consequences of each of those alternative courses of action. Individuals tend to think in terms of a limited set of data and a few plausible options at a time. In short, there are bounds, or cognitive limits, to their ability to examine a decision in a highly comprehensive manner.18 Therefore, the cognitive challenge is to make the decision more manageable for the human mind. Small wins enable individuals and groups to do just that, by gradually structuring a highly unstructured and complex problem.19

Complicated issues also induce frustration, stress, and personal friction. Psychologists have shown that individuals become anxious and tense when they perceive a problem as beyond their capability to solve. People typically evaluate their skills, as well as the capabilities of the groups and organizations in which they work, and they assess whether those capabilities match the demands of a situation. If they perceive a mismatch—namely, that the demands of the situation exceed their skills and competences—they become flustered, worried, and stressed. Those emotions make it difficult to actually solve the problem and make an effective decision. Therefore, the socio-emotional challenge is to keep everyone engaged and committed to a decision process by coping effectively with these intra- and inter-personal tensions. A "small wins" approach proves effective when a problem appears overwhelming to people. As Weick writes, "A small win reduces importance ('this is no big deal'), reduces demands ('that's all that needs to be done'), and raises perceived skill levels ('I can do at least that')."20

The decision to reform Social Security in 1983 represents a vivid example of how groups can use a series of small wins to build toward closure on a complex, divisive issue. In January of that year, a small group of senior policy makers—known as the Gang of Nine—came together to tackle a crisis facing the nation's Social Security program. Without a decision to implement reforms immediately, the program would have become insolvent, and millions of senior citizens would not have received their monthly checks on time.21

The White House and Congress had tried to reach a compromise for more than one year, but had been unable to do so. President Reagan had appointed a bipartisan commission to address the issue, but it too had not been able to arrive at an acceptable solution. People on both sides of the political aisle had become exasperated by the enormity of the challenge and the intensity of disagreement on the issue. With time running out in early 1983, four White House staffers and five former commission members came together to tackle the problem once again. They came to an agreement acceptable to President Reagan and House Democratic leader Tip O'Neill. One Gang of Nine member described how they arrived at a decision: "It was an incremental process. There were no major breakthroughs, just a bunch of small agreements that added up to a major package" [emphasis added].22

The Gang of Nine arrived at a series of critical agreements before trying to negotiate a solution to the Social Security crisis itself. Those agreements laid the foundation for further constructive debate about various alternatives for reform. First, they argued about, and ultimately settled on, a set of economic and demographic assumptions regarding matters such as future economic growth, inflation, population growth, life expectancy, etc. Second, based on those assumptions, they reached agreement on the size of the overall problem ($168 billion in the short term) that they were trying to solve. Finally, the Gang of Nine agreed that any solution must be composed of 50 percent tax cuts and 50 percent benefit reductions. That principle, or criterion, would guide the evaluation of all options. Building on that common ground, the Gang of Nine debated various alternatives, and gradually began to concur, one by one, on a series of tax-increase and benefit-reduction proposals that comprised the final solution that they recommended to President Reagan and the congress. For instance, early on, the Gang of Nine agreed to delay cost-of-living increases. Later, they came to the conclusion that they should accelerate payroll tax increases, and in the final stages of their deliberations, the team agreed to impose a tax on Social Security benefits for senior citizens who chose to continue working past the official retirement age. As the group agreed on one proposal after another, they gradually pieced together a solution that would make up the $168 billion shortfall in the Social Security program. Through a "small wins" approach, the Gang of Nine had tackled the "third rail" of American politics, brought together political opponents, and solved a complicated and stressful problem.

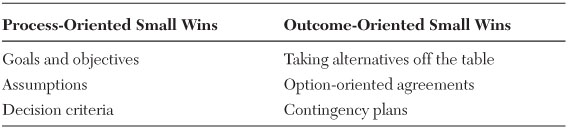

Types of Intermediate Agreements

The Social Security reform decision illustrates two types of small wins that leaders can seek during a contentious decision-making process (see Table 8-2). One type does not involve the ultimate courses of action to be implemented, but focuses on the elements of the decision process itself. For instance, the group agreed on core economic and demographic assumptions, and individuals concurred on the 50/50 principle to which all solutions had to adhere. Those process-oriented small wins do not constitute courses of action that could be implemented to address the problem at hand, but they did lay the groundwork for productive discussions about a range of possible solutions. Another type of small win consists of a partial solution to the problem that could be executed in conjunction with a number of other proposals. For example, the agreement regarding the taxation of benefits represents a concrete course of action that could be implemented by the federal government. The taxation of benefits, by itself, could not solve the Social Security crisis, but it represented a small piece to the complex puzzle. It proved to be a critical outcome-oriented small win. As leaders strive for closure on complex issues, they need to search for opportunities to secure small wins of both the process and outcome variety.

Table 8-2. Examples of Small Wins

Process-Oriented Small Wins

Although many types of process-oriented small wins exist (refer to Table 8-1), leaders would be hard-pressed to reach sustainable closure on a complex issue without agreement on three key elements: goals, assumptions, and decision criteria. In nearly all decisions, management team members approach an issue with a mix of competing and shared goals. The functional areas, geographic units, and lines of business within a firm do compete with another to some extent, and their interests are not aligned perfectly. Moreover, individual executives have personal goals and ambitions that may conflict with the aspirations of their colleagues. To reach closure on a complex issue, leaders cannot eliminate clashing interests among their subordinates, but they can and must find common ground in terms of a super-ordinate goal about which managers can all agree.23 As Stanford scholar Kathleen Eisenhardt and her colleagues discovered in their research on 12 senior management teams in high-technology firms, "When team members are working toward a common goal, they are less likely to see themselves as individual winners and losers and are far more likely to perceive the opinions of others correctly and to learn from them."24

In the Social Security decision, everyone recognized the common goal—restoring the solvency of the program—from the outset. However, some people held optimistic assumptions about economic growth, inflation, and the like, whereas others possessed a more pessimistic outlook. According to political scientist Paul Light, one participant felt that the early deliberations were "clouded by massively incongruent assumptions and datasets."25 Dissimilar assumptions caused people to define the size of the problem quite differently. The Gang of Nine could not agree on a solution if they could not settle on the size of the deficit that needed to be closed. By reviewing historical data trends together, the group members came to an agreement on their economic and demographic presumptions. Senator Patrick Moynihan pointed out that focusing on hard facts helped immensely: "Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not to their own facts."26

Larry Bossidy, former CEO of Honeywell International, and consultant Ram Charan have pointed out that any effective strategic planning process must include a healthy discussion and debate about what managers assume will transpire in the external environment in the years ahead. They also have stressed that achieving a common view with regard to those presumptions is critical to achieving closure on contentious issues and moving forward smoothly and efficiently on the execution of a strategy. Reflecting on Bossidy's experience at Honeywell, they wrote:

Synchronization is essential for excellence in execution and for energizing the corporation. Synchronization means that all the moving parts of the organization have common assumptions about the external environment...Debating the assumptions and making trade-offs openly in a group is an important part of the social software...As they construct and share a comprehensive picture of what's happening on the outside and the inside, they hone their ability to synchronize efforts for execution. And they publicly make their commitments to execute.27

Finally, an agreement on decision criteria can represent a critical small win that propels a group toward closure on a contentious issue. Leaders must consider a wide range of factors when comparing and contrasting alternative courses of action. In fact, many decision-making experts in academia and consulting have argued that managers make more effective choices when they consider a broader array of criteria, including both "hard" (quantitative) and "soft" (qualitative) factors.28

Of course, with such a wide range of factors to be considered, some managers may not recognize that they are evaluating a set of alternatives on dimensions that differ from those employed by their colleagues. It becomes difficult to make progress on a complex issue if people do not agree on the manner in which they will judge each option. When people discuss their evaluation criteria in an explicit fashion and settle on a set of factors to be used to examine each proposal, they often find that it helps them break deadlocks or impasses in the deliberations. Moreover, driving toward a common set of criteria can help dislodge some individuals from entrenched positions, encourage them to look at options in a whole new light and, ultimately, move a group toward closure. As one executive told me, "In order to get people to come together...we had to at least give them the opportunity to be comparing apples to apples."

Outcome-Oriented Small Wins

When it comes to selecting an actual course of action, leaders may piece together a series of partial solutions to address a large, complex problem, as the Gang of Nine did in the Social Security reform decision. Leaders also may emulate Eisenhower, who sought agreement on one element after another of a broad overall strategy. Each of these approaches takes advantage of the power of small wins. However, even when leaders are working toward one major final choice, as is sometimes necessary, they can seek a few types of outcome-oriented small wins along the way that can help them reach closure in a timely manner.

First, my research suggests that effective groups agree to eliminate options at critical junctures, rather than trying to simultaneously evaluate the entire set of feasible alternatives and select the single best course of action. For example, in one of the strategic alliance decisions described in an earlier chapter, the CEO explained how his team pared the list of options over time:

It was a winnowing process. What we were doing was taking things, gradually taking things off the table. In my mind, what you don't want to keep doing in a decision-making process is having to review all the alternatives over and over. You've got to start taking alternatives off the table.

Each time a group can agree to eliminate even one option, they secure a small win that may bring new allies together, shift the formation of coalitions within a management team, or break down some barriers among opponents. Taking one or more alternatives off the table also may cause some individuals to reexamine the remaining options from a new perspective, and perhaps to rank those proposals in a different order.

In contrast, some groups do not agree to eliminate options systematically, but instead, they try to revisit an entire array of alternatives repeatedly. Those teams tend to find their task cognitively overwhelming, particularly when a wide range of options exist. They find it harder to reach closure, or if they do reach an agreement, it represents a "mediocre compromise" that does not hold over time. For instance, reflecting on an important resource-allocation decision at his manufacturing firm, one executive explained how the management team's discussions seemed to wander aimlessly among five alternatives. Finally, the leader tried to build a patchwork solution that incorporated elements of each proposal. The staff member lamented, "We went through this whole harangue and analysis of all the options...and I think at the end of the day, it was sort of a decision. Maybe it's a compromise. We kind of did a little bit of everything."

Another type of small win, or intermediate agreement, occurs when managers make a tentative choice contingent upon specific events unfolding in the near future. In those instances, managers bridge their differences and move toward closure by agreeing to move forward definitively, but only if certain events transpire in the near future. For example, in the international joint venture decision described earlier, managers reached a tentative decision subject to certain conditions. This approach represented much more than a simplistic "keep your options open" mentality. The team agreed on a very specific set of parameters that needed to be negotiated with the alliance partners before moving forward with the joint venture. This approach solicited the support of those who liked the choice of partners, but had grave concerns about becoming a minority member of the joint venture with limited voice/influence on important matters. In a capital investment decision at another manufacturing firm, an executive explained that his management team came to a similar contingent agreement during a sometimes contentious decision process.29 In that case, the management team agreed to conduct a major facility modernization project, but only if the firm could secure some tax incentives from state and local governments. As one executive explained, "We said we are going to do this, but we are going to do this if we can get x, y, and z...It was always contingent on certain events happening." This approach secured the support of those managers who recognized the many merits of the project, but did not believe that the financial benefits justified the size of the capital investment.

In some sense, this decision-making practice resembles a "real options" approach to making progress on a complex and ambiguous issue. A "real option" exists when firms have the ability to delay investments and decisions until they acquire additional information.30 In these situations, managers must "purchase" this option by making a small investment at the outset. That up-front spending may, for instance, involve building a prototype of a new product and garnering customer feedback. Managers may agree to launch a new product line, but only provided that customers react favorably to a simple prototype, and/or that rivals do not beat the firm to market with a more advanced product. This "option" approach to decision making may help team members bridge their differences of opinion and move beyond an impasse. It helps to alleviate people's concerns about a decision prior to committing to full-scale implementation. Moreover, this practice provides an opportunity for additional learning prior to a final decision, and allows managers to resolve critical areas of uncertainty before moving forward in a definitive fashion.31

Finally, leaders may propel a group toward closure, and find an important patch of common ground, by seeking agreement on contingency plans that could be enacted during implementation if environmental conditions change. Many scholars and consultants have recommended a flexible approach to decision making when faced with high uncertainty.32 A good backup or contingency plan provides managers with a thorough assessment of the risks associated with a decision, as well as a strategy for mitigating those risks. Contingency plans differ from the options approach described earlier, because managers do not wait to move forward with full-scale implementation, but they maintain a backup strategy for adapting their course of action if external conditions change substantially.

An agreement on a contingency plan may propel a group toward closure on a contentious issue, because it may help people with reservations about a decision to become more comfortable with the risks involved. Before settling on a contingency plan, some members of a management team may not feel comfortable supporting a particular proposal because they see a large potential downside under certain scenarios. They may present a worst-case scenario, and while acknowledging that it is improbable, still express their reservations about a decision that could produce that undesirable result. People may become more willing to endorse and commit to a decision if a group has developed and agreed on a plan for adapting the chosen course of action if a worst-case scenario begins to unfold during the implementation process.

Shifting into Decision Mode

Adopting a "small wins" approach may be effective, but leaders may still find it quite difficult to shift into decision mode. That is, they find it challenging to close down debate and act as the arbiter if team members have not been able to agree on a final decision. In these situations, leaders can become uncomfortable, or they can bring deliberations to a close in a way that diminishes satisfaction with the decision process and buy-in for the final choice. Some leaders may even experience anticipatory regret—i.e., strong nagging doubts that preclude them from making a tough call and result in delays that prove costly in the competitive marketplace.

Leaders may take three steps to make a smoother final transition from deliberation to decision. First, leaders can develop a clear set of expectations regarding how the final decision will be made, so that there are no misunderstandings within the management team. Second, they can develop a language system that helps them communicate how their role in a decision process will change at a critical juncture in order to achieve timely closure. Finally, leaders can build a relationship with a confidant who can not only offer sound advice, but also bolster the leader's confidence when they become tepid and overly risk averse in the face of high levels of environmental turbulence.

Leaders need to develop clear expectations about their role in the decision process if they hope to achieve sustainable closure. Suppose that team members believe that a leader will strive for unanimous agreement first, and then make the final call only if such congruence cannot be achieved. They will be surprised, and perhaps rather angry, if they find that the leader simply solicits advice in a series of one-on-one meetings and then announces a final decision, without ever convening a meeting at which all parties can exchange their views. That disappointment and anger may cause individuals to resist a speedy decision that the leader has made. In such circumstances, an apparent instance of timely closure can unravel rather quickly during the early stages of implementation. Leaders need to state clearly and plainly how they intend to garner input and then use that advice and data to make a decision. When they speak about "teamwork," they need to be clear that they do not mean democracy, nor do they mean autocratic rule. They also need to forewarn their staff members if, for good reason, they intend to make a particular decision largely without input from others.

Organizations often find it helpful if a leader has a language system for communicating how his role can and must change when the time comes for debates to end and final decisions to be made. Jamie Houghton, long-time CEO of Corning Incorporated, developed a simple way of talking openly about how he intended to participate in senior management team deliberations, and ultimately, bring them to a close. David Nadler, a consultant for many executive teams, explains Houghton's language system:

He talked about wearing "two hats." In his terms, there were times when he wanted to be a member of the team, to argue, to test ideas, to have people push him, to get into the rough and tumble of the team's work. In those cases, he saw himself as "one of the boys," and he talked about wearing a "cowboy hat." At other times, he was in the position of CEO, making a decision. In those cases, he was not looking for testing, push back, or argument. Instead, he would be wearing the "bowler."33

The metaphor may sound a bit odd, but it proved helpful because it made a clear distinction between his role and the team members' roles in the decision-making process. The two hats helped Houghton and his direct reports talk candidly about the stage of the decision process at which they stood. Nadler reports that team members often referred to the two types of hats during meetings, seeking to clarify whether the debate could continue or whether the time had come for Houghton to make the final decision. Houghton also could signal to the team that the "bowler" was coming soon if they could not reach agreement on a controversial issue. One could imagine that team members in a protracted disagreement might seek rapid opportunities to find common ground, if they knew that the "bowler" was coming in the near future.

On some occasions, leaders experience moments of indecision when faced with a complex issue, ambiguous data, and environmental instability. The team members know that the leader will make the call, and they clearly understand their roles, yet the leader himself cannot make the final leap. Stanford scholar Kathleen Eisenhardt argues that, in those instances, leaders may find it helpful to have a highly experienced confidant who can act as a sounding board. By walking through the analysis and conclusions one final time with that trusted adviser, the leader can become more comfortable with the decision that he is about to make. As Eisenhardt explains, a trusted counselor can "impart confidence and a sense of stability" in uncertain times, and enable leaders to overcome the anticipatory regret that often causes costly delay and indecision.34

Sustaining Closure

After a decision has been made, leaders need to make sure that they adopt a disciplined approach so as to sustain closure. Individuals who disagree with a decision often would like to re-open the deliberations. If leaders have directed a fair and legitimate process, they should not allow others to revisit a decision that has already been made. They need to affirm that the case is closed. Paul Levy adopted such a disciplined approach at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Doctors and administrators at the hospital had become accustomed to revisiting decisions about which they disagreed whenever they felt it was to their benefit. Prior management had allowed such dysfunctional behavior to persist for years. Levy intervened when such detrimental conduct surfaced during his time as the chief executive, making sure that everyone understood that they could not revisit past decisions so long as they had been given a fair opportunity to voice their opinions earlier. In World War II, Eisenhower too needed to maintain discipline when powerful field commanders tried to continue debates that had long been brought to a close. At those times, Eisenhower often stressed the importance of "unity in command."

Leaders should not, however, remain stubbornly attached to a course of action, no matter what transpires after a decision has been made. Under certain circumstances, they should revisit past choices and re-open a matter for discussion and debate. In particular, decisions should be reexamined if extensive amounts of new information become available, or if several critical assumptions made during the decision process are proven to be false. A leader also might reconsider a past decision if it elicits unexpected and potentially deleterious responses from customers, rivals, and/or suppliers. Finally, issues may be re-opened for discussion if a subsequent initiative requires adjustments in past choices so as to ensure that the organization's entire set of activities and decisions remained aligned to achieve overall firm objectives.

The Importance of Trust

Fair and legitimate process helps build commitment, and small wins make it easier to navigate controversial deliberations and find solutions that people can endorse. In the end, however, leaders need to be trusted if they want to reach closure in a timely fashion and have people support and commit to that decision. Employing fair decision-making processes helps to build trust in a leader, as many studies have shown, but that is not enough.35 Leaders need to work constantly, in all that they do, to maintain their credibility and sustain the confidence that others have in them. If people trust a leader wholeheartedly, they are more likely to put aside differences of opinion and commit to a chosen course of action.

Trust and credibility do not come overnight, and they do not derive simply from a past track record of making good decisions and accomplishing positive results. Take, for example, the tragic case of the 1949 forest fire in Mann Gulch, Montana, that killed 12 United States Forest Service smokejumpers. Wagner Dodge, an experienced and accomplished foreman, led the team of firefighters assigned to drop from an airplane and fight the fire in the gulch on August 5, 1949.36

Roughly one hour after the smokejumpers landed on the ground, the blaze accelerated dramatically. Dodge and his crew tried to sprint to safety at the top of a ridge. He soon came to the realization that the crew could not outrace the blaze. Dodge came to a rapid, intuitive decision without consulting with any of his crewmembers; in fact, he invented a tactic that no one had ever employed. He bent down and lit a small fire in the grassy area roughly 200 yards from the top of the ridge, placed a handkerchief over his mouth, and lay down in the smoldering ashes.

Dodge's crew did not understand what he was trying to accomplish. He pointed to his fire and yelled, "This way! This way!" Imagine what the smokejumpers thought as they watched Dodge pull out his tiny matchbook, a raging fire directly behind him. One firefighter described his impression at the time: "I thought, with the fire almost on our back, what the hell is the boss doing lighting another fire in front of us?"37 As the crew raced by, one person reacted to Dodge by shouting, "To hell with that! I'm getting out of here!"38 Everyone ran past Dodge, ignoring his frantic pleas. Sadly, all but two of the crewmembers perished in the race for the top of the ridge, whereas Dodge emerged completely unscathed after just a few moments. The fire blew right over him, because he had deprived it of grassy fuel in a small area.

Why did these men fail to commit to Dodge's decision to lie down in the smoldering ashes? He certainly had official authority as the foreman, and he had a solid track record. Furthermore, he had far more experience than the other smokejumpers. However, he had not developed a strong reservoir of credibility and trust. He had not participated in a three-week training session with the other crew-members during that summer. In fact, many of the men had never worked with Dodge prior to that day. As leadership expert Michael Useem has said, he had a "management style that fostered little two-way communication."39 Many smokejumpers considered Dodge to be a man of few words. His wife concurred: "He said to me when we were first married, 'You do your job and I'll do mine, and we'll get along just fine'...I loved him very much, but I did not know him well."40 Dodge, in fact, did not even know the names of many men on his crew. After the tragedy, one survivor told investigators, "Dodge had a characteristic in him...It is hard to tell what he is thinking."41

During the landing and initial attempts to fight the fire, Dodge had communicated very little with his crew. He did not ask for their assessments of the situation or for their advice regarding how to fight the fire. Dodge also never explained why he chose to attack the blaze as he did. Even later, as he became more alarmed, he offered terse statements about the increasing gravity of the situation, rather than explaining his situational diagnosis in depth. Dodge had not established a foundation of credibility and trust through his prior actions and management style. Therefore, as Useem argues, people would not commit to his decision at the critical moment of crisis:

Without revealing his thinking when it could be shared, Dodge denied his crew members, especially those not familiar with him, an opportunity to apprehend the quality of his mind. They had no other way of knowing, except by reputation, whether his decisions were rational or impulsive, calculated or impetuous... If you want trust and compliance when the need for them cannot be fully explained, explain yourself early.42

The Mann Gulch case provides an extreme example of a leadership failure in a time of grave crisis. Certainly, a business leader is unlikely to find himself in such a dangerous situation with many lives in the balance. However, the tragic story illustrates vividly that a leader's style of communication and approach to making decisions shapes the extent to which he garners the trust and respect of his subordinates. Despite respect for a leader's expertise and position of authority, individuals will not put their full and complete trust in someone who has not been open with them, built a relationship with them, and given them some input on past decisions. They also will not put their faith in someone who has not explained his rationale for past choices or illustrated how he approaches and solves tough problems.

On the matter of trust, we must return to General Eisenhower. According to Ambrose, who spent a lifetime trying to understand this extraordinary military leader, Ike's trustworthiness proved to be one of his greatest virtues, as well as his greatest asset when it came to dealing with powerful and opinionated men such as Churchill, Roosevelt, Montgomery, and Marshall. After reflecting on many of Eisenhower's fine attributes, Ambrose concluded, "Over and above these and the other factors that led to his success, however, one stood out. When associates described Eisenhower, be they superiors or subordinates, there was one word that almost all of them used. It was trust."43