Three

Exploiting Institutional Voids

as Business Opportunities

INSTITUTIONAL VOIDS have a material impact on the operations of firms doing business in emerging markets.1 They are often a source of frustration. Foreign firms, for example, have trouble replicating models from their home markets in contexts that lack the intermediaries that underpin them. Institutional voids can even derail businesses, as illustrated by the challenges faced by software, film, publishing, and other companies operating in emerging markets, such as China, that have undeveloped intellectual property rights regimes. For domestic firms, institutional voids can frustrate attempts to get off the ground, raise capital, hire employees, and, later, match the resources and capabilities of foreign-based multinationals entering their home markets.

We have discussed institutional voids primarily as obstacles for companies doing business in emerging markets. But they can also be a source of advantage for those companies—foreign or domestic—that have local knowledge, privileged access to resources, or other capabilities that can help substitute for missing market institutions. Because institutional voids impose costs on market participants, entrepreneurial ventures that seek to fill these voids can create significant value. Although some market intermediaries are under the purview of governments, many can be owned and operated by private sector players—developed market-based multinationals, domestic companies, or upstart entrepreneurs. In this chapter, we look at how companies can identify and exploit opportunities to build full businesses by alleviating institutional voids.

Identifying Opportunities to Fill Voids

To build a business that fills institutional voids, companies and entrepreneurs first need to recognize the absence of an intermediary that would add value in an emerging market. As we have discussed, institutional voids occur when specialized intermediaries are absent. Intermediaries are the economic entities that insert themselves between a potential buyer and seller to bring these actors together and reduce transaction costs. In developed market economies, dozens of institutions facilitate the smooth functioning of markets.

Opportunities to fill institutional voids are often born of necessity. Multinationals entering emerging markets, for example, would prefer to focus on their core business but often need to invest in expensive efforts to build market infrastructure to execute their core businesses. Some void-filling businesses have been spin-offs of such initiatives. But how can other companies and entrepreneurs identify opportunities to build businesses dedicated to filling voids?

Taxonomy of Market Intermediaries

Given the bewildering array of such institutions in various markets, it is useful to think about these institutions from a functional perspective—that is, by the nature of the activity they perform in market economies. There are essentially six types of market institutions: credibility enhancers, information analyzers and advisers, aggregators and distributors, transaction facilitators, regulators, and adjudicators.

Each of these types of institutions performs a distinct task that is critical to the functioning of the market. These institutions help resolve the problems arising from information asymmetries and incentive conflicts between buyers (customers) and sellers (producers). Together, they constitute the network of institutions that makes markets work.2 This intermediation taxonomy is based on the institutional framework discussed in chapters 1 and 2 and provides a comprehensive picture of the market intermediaries that facilitate business transactions across product, labor, and capital markets.

Credibility enhancers provide independent assessments to support or validate business claims. To raise capital, for example, companies must convince providers of finance that the money being sought will be used in the way it is intended. This would be difficult if there were no third-party auditors to certify the credibility of the company and confirm a track record of creditworthiness. ISO (International Organization for Standardization) and other quality certification agencies serve a similar function in the product markets. The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) and Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC) do the same in the talent market.

Information analyzers and advisers find and generate information that facilitates business decisions, typically by providing data mining, number crunching, and consulting services. To develop and tailor products and processes that meet customer needs, companies rely on intermediaries such as market research firms to solicit information regarding the preferences of consumers or manufacturers. In the absence of a vibrant market research sector, identifying the kinds of goods to provide and performing detailed segmentation exercises would be significantly more difficult. Stock analysts and rating agencies play a similar role in financial markets, as do publications that rank universities and professional schools in the talent market.

Aggregators and distributors are the matchmakers in market intermediation, providing low-cost matching and other value-added services for suppliers and customers through expertise and economies of scale. Mass retailers add value as this type of market institution by compiling retail products into a one-stop shopping experience for consumers. Dedicated logistics companies aggregate the supply chain management operations of many companies by procuring inputs and disseminating outputs. Venture capital firms also provide this service by connecting businesses with sources of capital.

Transaction facilitators provide a transaction platform and facilitate buying and selling in markets. In searching for managerial talent, companies often rely on search firms to identify and screen potential employees, reducing many in-house human resource expenses. Online payment companies add to the cost savings of e-commerce by enabling consumers to complete transactions without waiting for checks or cash to get through the mail. Stock exchanges, eBay, and online job announcement sites are other examples of transaction forums in financial, product, and labor markets, respectively.

Adjudicators help market participants resolve disputes. Courts and arbitrators facilitate communication and resolution, and they issue rulings in a neutral setting.

Regulators and policy makers create and enforce the underlying rules that determine business engagement and industry direction. These intermediaries typically shape policy and make decisions to serve public and regional or national interests.

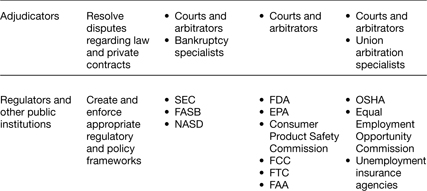

Table 3-1 applies this taxonomy of market intermediaries to U.S. markets, illustrating the range and depth of institutions underpinning developed capital, product, and talent markets.

The Value of Market Intermediaries

Many of the institutions of the marketplace are themselves privately owned and hence are driven by market forces. The fact that private sector intermediaries exist in a free market setting suggests that their services are valuable to buyers and sellers. John Joseph Wallis and Douglass C. North found that the transaction sector amounted to about one-half of U.S. GNP in 1970.3 Viewed another way, the fact that so much economic activity is devoted to market intermediation suggests the magnitude of the challenge faced by buyers and sellers in conducting transactions in the absence of intermediaries.

Second, the fact that so many different types of intermediaries exist, and that within each type still many more individual institutions exist, suggests that intermediation is based on deeply specialized knowledge and skills. Nurturing and deploying these skills are challenges; markets,can fail if any of the institutions in the network fails to fulfill its function. That is why it is a daunting task to build modern markets.

TABLE 3-1

Institutional infrastructure in a developed market (the United States)

Source: Tarun Khanna and Krishna G. Palepu, “Spotting Institutional Voids in Emerging Markets,” Note 9-106-014 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2005). Copyright © 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Publishing.

Third, as discussed earlier, the development of these institutions is a matter not only of economics but also politics. Market failures are beneficial to some economic actors, but they hurt others, so institutions that reduce market failures are not uniformly welcomed by everyone in an economy. Domestic and multinational companies can apply the taxonomy to identify the missing institutions—by function—and the opportunities that might exist in the intermediation space

Exploiting Opportunities to Fill Institutional Voids

With their expertise, credibility, and experience in developed market contexts, multinational companies may seem to have a natural advantage as market intermediaries. However, emerging market-based businesses bring their own advantages to these ventures. Domestic players often understand the institutional landscape of their home markets more intimately and can identify opportunities—and potential pitfalls—more readily.

Just as multinationals cannot fill some emerging market voids because of government regulation or other political considerations, void-filling domestic firms are limited in their ability to apply their business models outside their home markets. Even without international expansion, however, the sheer size of large emerging markets such as Brazil, China, India, and Russia presents big opportunities for intermediaries to grow into large domestic businesses. Businesses that fill voids in smaller emerging markets can grow into adjacent opportunities. A print media company, for instance, can expand into electronic media; a bank can diversify into asset management and investment banking; and a privately owned business school can set up a medical, law, or technology school. Such diversification often paves the way for these businesses to go global at a later stage.

Executing some types of intermediation, however, is difficult for existing companies. For instance, the success of information intermediaries such as financial analysts depends on their credibility. If a business group with many listed subsidiaries begins a fund, bank, or publication that would conduct such analyses, its credibility could be questioned.

Companies looking to build businesses based on the alleviation of institutional voids face many of the same challenges experienced by other companies operating in emerging markets. When developed market-based companies seek to transfer their intermediary role to an emerging market, they need to determine whether the market is ready for the intermediary and, if so, to what extent the home market model can be replicated in the emerging market and what adaptation is required.

For example, big box retailers—product market aggregators and distributors—rely on a sophisticated supply chain in developed markets. Replicating such a supply chain in an emerging market is complicated, and it is challenged by difficulties in the market’s hard as well as soft infrastructure. Distribution for a retail chain requires both hard infrastructure, like roads, to physically move goods efficiently, and soft infrastructure to, for example, reliably identify and assess suppliers and check the creditworthiness of customers. Both hard and soft infrastructures are underdeveloped outside large urban centers in many emerging markets. Intermediaries that help retailers build and connect their supply chains as well as those that provide market information and facilitate contracting are also missing or underdeveloped in emerging markets.

Similarly, credit card companies—product market transaction facilitators—are intermediaries that themselves depend on other intermediaries. The absence of consumer finance in emerging markets—the institutional void that credit card companies hope to fill—is the source of opportunity but also the source of challenges. The business model of credit card companies is particularly dependent on market infrastructure that has not developed or lacks the scope and sophistication of comparable intermediaries in developed markets. Credit information, which is credible and easily accessible in a developed market such as the United States, is not nearly as pervasive in emerging markets. Marketing through direct mail—a common practice for credit card companies—is difficult in emerging markets. Collection agencies, which credit card companies turn to in the event of delinquencies, are not as well developed. After working to overcome customers’ unfamiliarity with credit cards and gain acceptance in the local market, credit card companies face the challenge of managing in the absence of intermediaries on which their business models in developed markets depend.

Consider the ways in which global executive search firms—labor market transaction facilitators—have related their operations to the institutional voids in emerging markets. Some have focused almost exclusively on the global market segment, exploiting their relative advantages, whereas others have adapted their models and acquired new capabilities. Russell Reynolds Associates, for example, exploited its inherent advantages to gain a foothold in emerging markets (as it did in other foreign markets) by following existing multinational clients and maintaining its “one firm” approach to organizational culture and compensation structure.4 In Brazil, the company initially focused on the country’s privatizing telecommunications industry, where it exploited its industry knowledge. “It plays off our strength in telecom in London, in Atlanta,” said one company executive. “Those people are as much a part of the telecom practice as they are the Brazilian geography.”5

Similarly, in China, Heidrick & Struggles followed clients as it developed its operations, even opening an office in Chongqing, a giant municipality in central China—the first such firm to do so.6 The company also adapted its approach by joining with its JV partner, Beijing Leading Human Resources Consulting, in the development of an online jobs portal, Jobkoo, which catered to the top, or global, market segment.7 One Heidrick & Struggles executive described the value of flexible business models in emerging markets: “The last thing I want to do is go downstream. But if this works, I will apply the same technologies in India, in Central and Eastern Europe, and in Russia. This will be a completely separate brand, a completely separate company, and the way to create a revenue stream in the emerging markets while simultaneously building a future database for us. Could some of these ventures eventually cannibalize our business? Sure, but given the option of doing nothing, that’s a risk I’m willing to take.”8

Like other multinationals in emerging markets (as we discuss in chapter 4), the foreign intermediary adapted operations and acquired new capabilities to reach a different market segment in an emerging market—and hoped to transfer those capabilities to other emerging markets. Similarly, domestic companies with intermediary-based business models need to identify their sources of relative advantage in filling voids (such as local knowledge), acquire capabilities as needed, and determine which segment (or segments) they can serve.

As with any company operating in emerging markets, the firms that have been most successful in building businesses to fill institutional voids have been those that understand that business models cannot travel seamlessly to emerging markets; these companies adapt effectively and remain open to experimentation. Mapping the institutional context is a good first step. Intermediaries can use the taxonomy described here to identify the missing pieces of market infrastructure that might serve as entrepreneurial opportunities. By then auditing their capabilities, inherent advantages, capacity to adapt, and ability to acquire new capabilities, intermediary businesses can see how they match up to the opportunities identified.

TABLE 3-2

Case examples

| Strategic challenge | Examples |

|---|---|

Segmentation for intermediaries |

Blue River Capital in India |

Adapting intermediary models |

Deremate.com in Argentina |

Moving up the intermediation value chain |

Li & Fung in Asia |

Displacing substitute intermediaries |

Metro Cash & Carry in India |

In the rest of this chapter, we look at four companies that identified opportunities to fill various voids in different markets (see table 3-2). These examples illustrate the importance of identifying opportunities as well as the often wrenching challenges companies face when executing these opportunities.

Blue River Capital faced tough competition and execution challenges as it sought to fill voids in India’s capital markets. The investment firm differentiated itself by targeting a market segment eschewed by many rivals—middle-market, largely family-owned businesses—and exploiting institutional voids as barriers to entry. Deremate.com sought to replicate the success of auction site eBay in Argentina and found the need to adapt this model to the emerging market. Low barriers to entry in Argentina ensured that fly-by-night operators made competition tough. Further, the country lacked many of the other contextual features that made eBay successful in the United States. Hong Kong–based Li & Fung has identified and successfully filled a range of voids in the global manufacturing supply chain, relentlessly evolving its model and adding more value to customers by adding intermediation roles to its offerings. In many cases, institutional voids in emerging markets remain unfilled because of opposition from governments or other vested interests. Successful execution of these businesses requires a great deal of sensitivity to the impact of filling the void on various stakeholders. German wholesaler Metro Cash & Carry learned this lesson in India when it faced entrenched opposition having a stake in preserving the status quo.

Segmentation for Intermediaries: Blue River Capital

The growth and potential of the Indian economy, and the companies emerging within it, attracted investment firms of all stripes to set up shop in the country in the early 2000s—from Silicon Valley–based venture capitalists to global private equity behemoths to local entrepreneurial start-ups.9 While chasing the next Infosys or Bharti Airtel, these firms were also filling voids in India’s capital markets. India-dedicated private equity firm Blue River Capital was established in 2005 as this flood of foreign investors and financial services firms clamored to enter or step up their presence in the booming market.

Blue River differentiated itself from this competition by targeting a segment it identified as an underserved niche: middle-market businesses established and still managed by families or entrepreneurs. Shallow coverage of companies by research analysts narrowed the pool of companies targeted by foreign private equity firms looking for more known quantities—even at a premium—as they raced into a market that was relatively unfamiliar to them.

Blue River avoided this competition by targeting companies not covered by analysts, including private companies and public firms that were not actively traded or widely covered. Blue River also pursued investments in businesses outside the sectors typically pursued by global venture capital and private equity firms. Sectors in which Blue River invested—such as textile, packaging, and auto components—might be considered mundane and not particularly high-growth prospects in the United States, for example, but could become big businesses in an emerging market like India.

Blue River sought out high-potential, low-risk companies within a segment deemed risky by many investors because they were not prescreened and could be difficult to assess. As with other firms operating in emerging markets, intermediaries need different capabilities to target different segments. Blue River exploited institutional voids directly as sources of investment opportunity by targeting a segment containing more institutional voids (see figure 3-1)—but where it could exploit the relative advantage of its local knowledge. “If it were easy, then it wouldn’t be an opportunity,” a company executive said. “Because of all the complications, because of all the challenges, that creates the opportunity for the folks who are able to manage through that.”10

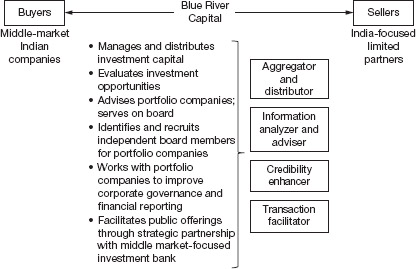

FIGURE 3-1

Segmentation for Blue River Capital

Providers of risk capital such as Blue River are important market intermediaries in any economy. Venture capital and private equity firms provide seed funding for start-ups and growth capital for companies looking to expand. The value proposition of these firms is particularly strong in emerging markets having other institutional voids in their capital markets. Service-oriented businesses, for example, often lack hard assets sufficient to serve as collateral for bank loans in markets without well-developed cash-flow lending facilities. In the taxonomy of market intermediaries, these firms serve primarily as aggregators and distributors of capital. As the first professional investor in portfolio companies, Blue River was an active investor, providing capital but also working closely with portfolio companies on strategy and a range of business issues and thereby serving several other intermediary functions (see figure 3-2).

Identifying and executing investments in Blue River’s target segment were difficult, resource-intensive processes. The firm sourced deals through the research of its own staff and leads from local investment banks, accountants, law firms, and deal brokers. In 2006, the firm reviewed 207 potential deals, issued ten term sheets, and conducted formal due diligence for three deals, all of which were completed. “Historically, you can say that India has this problem of a lot of tainted entrepreneurs or family businesses, and you do need local expertise to be able to identify who to partner with and who not to partner with,” said one Blue River executive.11 Blue River built its business on the relative advantages of its local knowledge—helped by its strategic partnership with Edelweiss Capital, a middle-market-focused investment bank—and its willingness to invest the time and resources to work with companies that would be outside the comfort zone of most foreign investors in terms of corporate governance.

FIGURE 3-2

Institutional voids filled by Blue River Capital

The absence of information intermediaries and background check services complicated due diligence for Blue River. The firm sought to minimize these risks by investing in firms that had track records long enough to assess meaningfully. Blue River began its due diligence with background checks on the management of prospective investments—a process that often concludes due diligence in the United States and other developed markets—even before evaluating the company in terms of its operations. To do so, Blue River needed to fill an institutional void; background investigation firms and the databases that provide raw data for such firms are undeveloped in India (although KPMG International recently started a background check service in the country). Blue River exploited its network and other sources to make inquiries about the management of potential portfolio companies.

Blue River explicitly sought out companies that needed to revamp financial reporting and corporate governance or needed help with other management issues. By working with portfolio companies on these issues, Blue River served as a credibility enhancer. One of Blue River’s portfolio companies, for example, did not differentiate between payables and receivables from one company with which it was both customer and vendor, essentially saying, “Let’s net it off,” according to one Blue River executive.12 But he also noted, “Family business does not mean a lack of professionalism.”13 Blue River looked for promising businesses with established track records that needed only to change business practices (and polish their organizations) to unlock and monetize their potential.

Blue River’s model required significant “handholding,” one company executive said, even before the firm committed capital to portfolio companies.14 After completing deals, Blue River developed templates for new portfolio companies that were establishing plans for organizational and other changes; the protocols covered the first six months after the investment. With each investment, Blue River insisted on changing statutory auditors, financial controls, and accounting practices; identified related-party transactions; and put the entrepreneurs and any family members working for portfolio companies on employment contracts. “Be more conservative in how you represent yourselves to the outside world,” Blue River told portfolio companies.15

Blue River has also worked with portfolio companies to develop boards of independent directors—including identifying candidates through its network—a practice that can add value to the firms beyond simply increasing governance credibility. “‘You should want something from your board,’” Blue River tells portfolio companies, according to one Blue River executive. “We say that these are people who will stay with you much longer than we will.”16

Blue River exploited a provision in Indian law under which contracts can supersede minority shareholder rights to demand rights above those that would be afforded conventionally, including seats on the boards of portfolio companies and approval over some business decisions, such as annual budgets, capital-raising initiatives, changes to senior management, and compensation. The firm knew that it would face resistance from portfolio companies to the organizational changes it sought to implement once they were in its investment portfolio. Blue River dealt with this challenge by investing in only those companies that were amenable to organizational changes. Still, managing the internal dynamics of portfolio company organizations, particularly those run by families, was a challenge. “Sometimes it’s like swimming in a sea of glue,” said one of Blue River’s operating advisers.17

To limit resistance, Blue River sought out companies undergoing transitions, particularly family-run firms in which a younger generation of family members was assuming management responsibility. More fundamentally, Blue River’s model required its willingness and ability to empathize with portfolio companies. “Arrogance here doesn’t work at all,” a Blue River executive reflected. “We tell them that we’re doing this for your benefit, and they respect us for it. You have to give people that sense of comfort that you’re not taking away business flexibility from them.”18

Intense competition from a range of players compelled Blue River to seek out a market segment where many potential rivals feared to tread, in large part because of institutional voids. The firm exploited its local knowledge and willingness to invest resources in corporate governance and organizational issues. Any investment firm fills a void by providing capital to businesses; Blue River differentiated itself by offering additional intermediary functions to a segment in which institutional voids served as both obstacles and opportunities. Like many successful intermediation businesses, Blue River developed a unique value proposition to an underserved segment.

Adapting Intermediary Models: Deremate.com

Market institutions often migrate from developed to emerging markets after decades of economic development.19 Many of the myriad new market institutions born of the Internet in developed markets were replicated in emerging market countries much more quickly. Soon after the online auction site eBay took off in the United States, for example, clones were established in many emerging economies. The experience of Deremate.com, one of the first players in Latin America, illustrates the challenges of replicating intermediaries in emerging markets.

eBay was an innovative market intermediary in its own right, but it flourished only because it was built on a foundation of other contextual features (such as high Internet penetration and familiarity with similar transactions through classified ads) and other market intermediaries (such as widely accepted payment systems and reliable delivery services). eBay clones arrived in emerging markets quickly but succeeded only as the institutional ecosystem around them developed.

Internet auction sites are direct market intermediaries, connecting buyers and sellers of goods through a Web site that serves as a transaction facilitator and pricing mechanism. Deremate—literally “at auction” in Spanish—saw the intermediary’s value proposition as particularly strong in developing markets by serving, for example, as a pricing guide for customers outside urban centers and without access to other information intermediaries and a useful tool for consumers with low incomes, in particular, to monetize assets (see figure 3-3).20

Deremate borrowed global institutions from its inception. Mindful of the power of first-mover advantage in its business and by fast-moving competition—including MercadoLibre.com, a rival founded by a group of graduates of the Stanford Graduate School of Business—Deremate sought assistance from developed markets to get its site up and running. The company partnered with Aucland, a French firm that had developed an online auction platform that operated in multiple European currencies and languages, a useful feature given that Deremate planned to expand beyond its home market, Argentina.

FIGURE 3-3

Institutional voids filled by Deremate.com

Internet auctions are useful as intermediaries only if the quality and quantity of their product listings are sufficient to attract potential customers. Deremate’s management initially listed personal possessions—and cajoled friends and family to do likewise—to help stock the site, but the firm faced challenges acquiring scale in its product listings. eBay had piggybacked on an existing market for collectibles to spur its early growth, but no similar market existed in Latin America. Moreover, even comparable intermediaries such as yard sales and classified ads were not particularly developed in the region. This barrier of unfamiliarity and the low level of Internet penetration in Latin America compelled Deremate to position itself initially primarily as a business-to-consumer (B2C) site, an easier proposition than building a consumer-to-consumer (C2C) base from scratch. Deremate’s marketing, meanwhile, focused on increasing awareness of its model, and the company segmented the market, targeting wealthy consumers through advertising on cable television.21

Institutional voids, such as underdeveloped payment systems and delivery infrastructure, challenged Deremate across Latin America. Forms of transaction varied widely across the region, from two parties exchanging goods in person and paying by check to the use of debit cards and third-party delivery. The company later established alliances with courier companies in each country to facilitate shipping.22

Currency fluctuations, language differences, and trust concerns, meanwhile, limited customer willingness to engage in cross-border transactions.23 As a Deremate executive noted, even eBay has not been able to compete independently outside the United States (with the exception of the United Kingdom and Canada) and instead has looked to acquire or partner in other foreign markets.24 Another institutional void—the absence of information intermediaries that might provide data on the marketplace—also challenged Deremate’s ability to manage the growth of its organization. “Nobody really understands how big the market is, how big it can be, and very well-reputed organizations disagree by orders of magnitude about the present size of the market, let alone the projections,” said one company executive.25

By 2000, Deremate had become a leader in the market and faced a “feeding frenzy” of bankers looking to take it public.26 Deremate had been valued by several Wall Street banks at more than $1 billion, but the IPO was canceled after the burst of the tech bubble.27 Many of Deremate’s competitors continued to spend aggressively, expecting equity prices to recover, but Deremate cut expenditures, focused on organic growth, and remained one of the region’s leading players in Internet auctions, along with MercadoLibre.28 The two firms had discussed merging sixteen times by mid-2002 but never reached agreement.29 eBay sought to enter Latin America through a partnership and, in October 2001, signed an exclusive strategic partnership agreement with—and took an 18 percent stake in—MercadoLibre.30 With its noncompete agreement with eBay set to expire in 2006, MercadoLibre sought to acquire Deremate. MercadoLibre bought Deremate’s operations in all but Chile and Argentina in 2005 and completed its acquisition with the purchase of those operations in 2008, reportedly giving MercadoLibre a 90–95 percent share of the Internet auction market in Latin America.31

It seems relatively easy to transfer the concept of a void-filling business to an emerging market, and this perception of ease, coupled with the palpable opportunity presented by institutional voids, often attracts significant competition. Deremate faced forty-two competitors in 2002, ten of which had received significant funding from institutional investors.32 The tremendous power of network effects in an intermediary business such as Internet auctions quickly winnowed the competition to essentially one—the firm that had partnered with the global leader in its business.

Replicating developed market-based intermediaries in emerging markets is much more easily conceived than executed. eBay was built on a foundation of market infrastructure that was not present or fully developed in Latin America at the time Deremate and other firms established their businesses. Contextual features challenged not only the ability of these companies to generate business activity but also their ability to manage their growth in a fluid, uncertain environment, and for others to value them. Void-filling businesses can change the context of emerging markets, but they are also dependent on an ecosystem that cannot be transferred overnight. Firms targeting these businesses need to audit the local business context and institutional voids to understand that ecosystem, adapt their models to that context, work to fill those other voids where possible—and otherwise be patient and manage expectations and organizations accordingly.

Moving Up the Intermediation Value Chain: Li & Fung

Li & Fung started by brokering deals between Western companies and Chinese factories in Guangzhou, China, in 1906.33 The entrepreneurial venture filled a void as a transaction facilitator between buyers and sellers that lacked a common language and shared business connections. The company, based in Hong Kong since the late 1930s, grew into a global giant by providing an ever-widening array of high-value-added intermediary services to global retailers and brands looking to exploit factor markets in emerging economies in Asia and elsewhere. Li & Fung has evolved from a pure transaction facilitator into an aggregator, distributor, credibility enhancer, information analyzer, and adviser in three lines of business—trading, distribution, and retailing—serving different sets of customers (see figure 3-4).

Li & Fung started out in basic trading and then operated as a sourcing agent for raw materials and consumer goods, first in China and Hong Kong and then in other Asian markets. The company was compelled to take on additional intermediary roles to move up the value chain as it tried to outpace declining margins. One company executive noted, “When my grandfather started the company . . . his ‘value added’ was that he spoke English . . . No one at the Chinese factories spoke English, and the American merchants spoke no Chinese. As an interpreter, my grandfather’s commission was 15%. Continuing through my father’s generation, Li & Fung was basically a broker, charging a fee to put buyers and sellers together. But as an intermediary, the company was squeezed between the growing power of the buyers and the factories. Our margins slipped to 10%, then 5%, then 3%.”34

FIGURE 3-4

Evolution of Li & Fung’s intermediary businesses

Source: Created by authors based on description of Li & Fung supply chain in Li & Fung Research Center, Supply Chain Management—The Practical Experience of Li & Fung Group, 2003, 28, 40, via Feng Bang-yan, 100 Years of Li & Fung: Rise from Family Business to Multinational (Singapore: Thomson Learning, 2007), 214–217.

Li & Fung moved up the value chain of intermediation from serving as a sourcing agent to developing full manufacturing programs for retailers and, later, breaking up supply chains to minimize costs and maximize efficiency and quality in each segment across different suppliers in different countries. “Managing dispersed production was a real breakthrough,” said one company executive. “We dissect the manufacturing process and look for the best solution at each step. We’re not asking which country can do the best job overall. Instead, we’re pulling apart the value chain and optimizing each step—and we’re doing it globally. Not only do the benefits outweigh the costs of logistics and transportation, but the higher value added also lets us charge more for our services.”35

Based on its deep knowledge of several thousand Asian suppliers from which it had sourced over many years, Li & Fung identified and sorted their capabilities, quality, and credibility, matched them to the design and manufacturing needs of Western customers, and met stringent delivery requirements despite the poor quality of local infrastructure. For example, as one company executive noted, the company could help a retailer save costs in putting together a toolkit by sourcing wrenches from a factory in one country and screwdrivers from another. “That has some value in it—not great value, but some.”36

Through dispersed production, Li & Fung exploited the scale of its reach and the quality of its internal information-sharing systems to respond to customer demands with speed and flexibility, adding more value for customers that needed just-in-time services. By reserving undyed fabric and mill capacity in advance, for example, Li & Fung enabled apparel retailers to respond to changing customer tastes and fashion trends more quickly and to limit excess out-of-style inventory. The company knew that simply squeezing costs by identifying lowest-cost producers and improving operations in hard infrastructure was not a sustainable source of competitive advantage. Instead, Li & Fung sought to improve margins from “the soft money,” as one company executive called it, in distribution and value-added services. “It offers a bigger target, and if you take 50 cents out, nobody will even know you are doing it. So it’s a much easier place to effect savings for our customers.”37

Li & Fung earns this soft money by filling voids in soft infrastructure. The company alleviates information and contracting problems for its customers, exploiting its knowledge of suppliers and taking on the risk of contracting with them. Through services as wide ranging as product planning, executing design, managing quality control, managing customs requirements, and handling shipping consolidation and other logistics, Li & Fung fills a range of voids.

In terms of the taxonomy of market intermediaries, Li & Fung serves a number of roles for various constituencies through its three main business lines: trading (Li & Fung Limited), distribution (Integrated Distribution Services), and retailing (Li & Fung Retailing Group). The company is an information analyzer and adviser in assessing suppliers by price, quality, reliability, speed, credibility, regulatory compliance, environmental standards, and labor conditions. The company also evaluates the broader institutional contexts of the markets in which it contracts in light of concerns over protectionism and quotas—a service that is particularly important for its textiles and apparel customers. Li & Fung continually evaluates suppliers and seeks out new production partners based on labor costs, quality, and other features.

The company is also an aggregator and distributor of materials, goods, and information with its wide and deep reach. For suppliers, Li & Fung serves as a credibility enhancer, a role that connects it to global brands and retailers. As one company executive described Li & Fung’s business, “In a sense, we are a smokeless factory. We do design. We buy and inspect the raw materials. We have factory managers, people who set up and plan production and balance the lines. We inspect production. But we don’t manage the workers, and we don’t own factories.”38

As with any strategy, Li & Fung also needed to determine what it would not do in terms of intermediation. “I could expand the company by another 10% to 20% by giving customers credit,” one company executive said. “But while we are very aggressive in merchandising—in finding new sources, for example—when it comes to financial management, we are very conservative.”39

To deliver its value-added services, Li & Fung adapted its organization and operations both to the institutional contexts of the markets in which it operated and to the high-touch needs of its customers. Partnering with suppliers in Bangladesh, for example, offered cost savings, but Li & Fung needed to manage in light of the market’s underdeveloped hard infrastructure, such as communications, that hindered the company’s IT-intensive model. Li & Fung also aligned itself with customer needs by organizing its operations in small, autonomous, customer-dedicated units. These units sometimes went so far as to tailor their operations to the business processes and software systems used by their customers. The company sought out entrepreneurial managers in its organization—“little John Waynes,” as one company executive dubbed them—to lead these units and incentivized them “to move heaven and earth for the customer.”40

Li & Fung moved up the value chain and out of its home market through targeted acquisitions. The company sought to fill the mosaic of its place in the intermediation space by buying other intermediaries having specific capabilities or industry expertise it lacked. The company also pursued acquisitions to move up the value chain by buying companies that specialized in private label and proprietary brands. These acquisitions gave Li & Fung an onshore presence in the U.S. market, allowing it to be closer to customers and liaise with them at the beginning of product planning and identify new services the company could provide. “Instead of stopping our role once the ship is loaded, we are moving with the goods into the U.S.,” said one company executive. “That way we get more jobs and more value.”41

Shaken by the U.S. recession—and looking to cut costs wherever possible—some major U.S. retailers saw Li & Fung’s services as a particularly valuable proposition in 2008–2009. Liz Claiborne, for example, sold its sourcing operations to Li & Fung in early 2009.42 “This economic recession is more Darwinian,” Liz Claiborne’s CEO told BusinessWeek. “Now is the time to reinvent your business model to be more competitive.”43 Through acquisitions of customer sourcing operations and rivals, Li & Fung sought to accelerate its growth through the recession.44

Li & Fung’s success epitomizes the potential for firms to exploit globalization opportunities, technological capabilities, and deep local knowledge in cross-border intermediation. The intermediary’s business evolved incrementally over time and successfully adapted to different contexts.

Our next example illustrates how intermediary-based businesses often displace powerful vested interests profiting from inefficiency and can provoke opposition even to highly compelling—and void-filling—value propositions.

Displacing Substitute Intermediaries: Metro Cash & Carry

Metro Cash & Carry, a division of German company Metro AG, has been an effective wholesaler in many emerging markets.45 The Düsseldorf-based company sells everything from meats and vegetables to napkins, toothpicks, and hard goods as a B2B supplier to restaurants, hotels, and other businesses. Although Metro has a large and long-established presence in Western and Eastern Europe, the company has recently pushed into emerging markets such as China, India, Russia, Turkey, and Vietnam.

Although food varies widely as a percentage of sales in Metro’s outlets, the company’s operations often change the context of food supply and distribution in emerging markets where food is a significant line of its business. To supply its stores, the company has built direct links with farmers in rural areas to bring their goods to urban markets. As Metro enters emerging markets, it fills several roles described in the taxonomy of market intermediaries (see figure 3-5). The company serves as a transaction facilitator through its stores, connecting sellers of produce (farmers) with food buyers (restaurants, hotels, and other businesses). Metro is an aggregator and distributor for buyers, offering one-stop shopping for a range of goods, and for sellers, offering farmers and other businesses access to a range of customers. As a reliable seller of goods, Metro helps businesses reduce their inventories. As a reliable buyer of goods, the company helps farmers reduce risk. The company is also a credibility enhancer, helping ensure the quality of goods sold, and an information provider, relating market information to farmers. Moreover, by shifting transactions from roadside markets to state-of-the-art wholesale stores, the company’s operations bring primary products into the tax net, a boon to local governments.

FIGURE 3-5

Institutional voids filled by Metro Cash & Carry

Metro expanded quickly in some emerging markets. Within five years, the company had opened twenty-two stores in Russia, an expansion helped in part by support from Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov. Metro faced significant competition in China from a wide range of players; within five years, it had eight stores but opened seventeen more in the few years thereafter. The slower pace in China was attributable in part to the extensive local negotiations needed to open each outlet, even with a large local JV partner.

In India, local opposition proved even more problematic. Metro’s value proposition was particularly strong in India because of the waste and inefficiency that plagued the country’s food distribution system. “Everything that we bring is positive,” said one company executive. “It’s positive for the farmer; it’s positive for the retailer. The cost saving gets passed right down. The immediate mind-set in people is, ‘This is too good to be true.’ Everybody wins—except us, in the beginning.”46

In 2000, the company received approval from national authorities to open its cash-and-carry outlets in India. Metro then opened its first two stores in Bangalore in 2003. As a high-tech hub with a significant presence of foreign companies, the city was thought to be a particularly promising entry point for the wholesaler. Metro’s first outlets were only half-stocked, however, because the company could not purchase fruits and vegetables directly from farmers, a practice that was central to its business model in other countries. The Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act required that produce in India be sold only through government-run auction markets called mandis.

Designed to prevent the exploitation of farmers by landed gentry in the 1950s, the APMC Act stifled the creation of genuine produce markets, hurting farmers, who were subjected to the mandis’ inefficiencies. Although central government leaders had decried the APMC Act as an anachronistic impediment, it remained in force in the state of Karnataka—where Bangalore is located—and subject to the will of local authorities, who neglected to make good on continued promises to Metro to lift the measure. Metro’s supporters in the central government offered little assistance because political power was decentralized.

Metro soon faced vocal public opposition and even protests from groups opposed to foreign investment and the traders who profited from the inefficiencies in the mandi system. “The middle man normally in all of these countries, they only have one investment: it’s a cellular phone,” said one Metro executive. “They buy cheap and sell high. And they fuel the governments.”47 Metro attracted particular attention in the media and from protesters by virtue of the large size and sophistication of its stores and the fact that Metro was the first major foreign big box operator to enter India.

The company struggled to convince the public that it was a wholesale operation and was not encroaching on the turf of local retailers, all of whom sold directly to the end consumer as retail players. At the same time, it needed to confront the political opposition with sensitivity, as one company executive recalled: “The farmers wanted to go on the street to protest for us. The small traders wanted to go on the street to protest for us. We said no, because you only generate a conflict. Maybe for a short time you are winning, but then you are a political instrument, and you don’t have control on that. You have to be very balanced, especially in an environment like India where there are political chameleons that are changing from today to tomorrow.”48

Market contexts are the product of history, culture, and politics as much as economics. A changing market context thus poses historical, cultural, and political challenges that are difficult to overcome, particularly for multinationals. Even without perishable foods—which typically represented 30 to 40 percent of an outlet’s sales—Metro’s stores in Bangalore achieved higher sales than foreseen in the budget, an indication that the cash-and-carry model was accepted by customers. As a foreign company displacing established interests in a sensitive political environment, however, Metro was vulnerable to opposition from other stakeholders.

Multinationals bring many business advantages to emerging markets when they seek to fill institutional voids, but they must work to overcome entrenched interests and latent suspicions to be seen as a partner in progress. One company executive explained:

We know that the concept is right for India. We can communicate this, but you have to then build trust to be given the chance to show you can do it. The trust leads then to the operation, leads to credibility, leads then to the speed of expansion that we will have. Once the concept is really in place and we can show the benefit to the customer, the benefit to the supplier, the benefit to the taxman, the benefits all around, then everybody will support it. And then you have a different mind-set. But in a developing market, if you come in as a foreigner, there’s a lack of trust. That is a big challenge for any foreign company going into a developing market, because ultimately we are there to make money. You can make money, and everybody can still benefit, but that’s very difficult in a developing market for people to accept.49

Metro expanded its operations to other cities in India, but the APMC Act continued to be a barrier in Karnataka as of 2008. As one company executive noted, “There’s a very nice saying in India, which is, ‘You might have the clocks, but we have the time.’”50

Emerging markets develop not through the simple addition of intermediaries serving to connect buyers and sellers but through an incremental, often halting, process of development. Intermediary-based businesses with strong value propositions must contend with the informal institutions and substitute intermediaries that have a stake in the status quo—illustrating the critical importance of carefully mapping the institutional context in emerging markets.

Filling Voids in Emerging Markets

Intermediaries face tough contextual challenges, competition, and incumbent substitutes, as the examples in this chapter show. Any company seeking to build a business based on filling institutional voids in emerging markets should first recognize that an institutional void exists and that filling it could create significant value (see toolkit 3-1).

Prospective intermediaries need to match their capabilities to the broader institutional context of the emerging market. Void-filling multinational businesses need to determine whether the market is ready for their services or whether they should emphasize opportunities elsewhere. Domestic firms need to identify a source of relative advantage in filling the void.

Next, prospective intermediary businesses need to identify which segment of the market they can serve with their current capabilities or which skills or other capabilities they need to acquire to serve it. Intermediaries often depend on other market institutions or contextual features, so these businesses need to map, evaluate, and adapt accordingly. Firms often need to fill other voids as a means of serving their primary intermediary functions. As they establish themselves, firms need to consider how to expand into adjacent intermediary roles and grow their businesses by adding value through their intermediation. Finally, successfully changing the market context requires a great deal of sensitivity to stakeholders that are affected or displaced and the broader ecosystem that often underpins market intermediaries.

Toolkit 3-1

Toolkit for Intermediaries Looking to Fill Institutional Voids

Where can we identify voids to fill as entrepreneurial opportunities?

What segment can we reach?

- What other contextual features or market institutions does this intermediary role depend on in developed markets?

- How do we need to adapt this intermediary-based business to the local context?

- How can we expand our business into adjacent intermediary services and move up the intermediation value chain?

- What vested interests are we displacing or might we encounter as we seek to fill this void?