Five

Emerging Giants: Competing at Home

UNSHACKLED BY economic liberalization, entrepreneurs and domestic companies in emerging markets are aggressively pursuing growth opportunities at home and overseas.1 Alongside the fast economic growth of their home markets, successful emerging market-based companies are flourishing, regularly registering double-digit annual revenue growth and figuring prominently in global deal making.

Globalization and liberalization have also intensified competition in these firms’ home markets as multinationals from developed markets enter with all the advantages outlined in chapter 4: established global scale, brands, technology, financial muscle, talent, and organizational capabilities. Beyond foreign competition, emerging market-based firms have faced each other in tough local competition and have confronted the challenges of institutional voids in their home markets—voids that frustrate their access to talent, technology, and capital. After establishing strong positions at home, some of these domestic firms have been able to access global capital, tap in to customer segments outside their home markets, make acquisitions overseas, and find new partners to develop their businesses.

A small but growing set of these companies has built world-class capabilities to challenge global rivals in their home countries and even in developed markets. Cemex (Mexico), Infosys (India), South African Breweries (now SABMiller), and China’s Haier Group are all making marks on international commerce by competing successfully worldwide. Other companies, such as Bharti Airtel (India), China Light and Power, Koç Group (Turkey), and Petrobras (Brazil), are viewed as world-class companies because they have successfully grown their businesses and defended their turf domestically.

We use the term emerging giants to refer to these successful and globally competitive companies from emerging economies, which are thriving not as a result of protectionist regulatory barriers but on the basis of sustainable competitive advantage. This chapter looks at how emerging giants are confronting the strategic choices of responding to institutional voids as they look to acquire competitive advantage in their home markets.

In an absolute sense, institutional voids are an encumbrance. However, successful emerging market companies can use the fact that they are comparatively better placed to circumvent these voids—relative to incumbent multinationals—as the thin end of the wedge. Examining the origins of these firms is useful for developed market-based companies so that they can understand their rising competition, and for entrepreneurs in emerging markets to appreciate the models these companies have used to develop from small ventures into major global firms.

Facing Institutional Voids and Multinational Competition

How have emerging market-based companies grown beyond their still-developing home market contexts to become globally competitive? The rapid growth of their domestic markets has helped these firms fast-track their development, but they have been able to enter the competitive global arena only by first managing the prevalence of institutional voids and surviving the entry of multinationals into their home markets.

With the advantages of their global brands and resources, multinationals can quickly displace domestic companies from the global segment of emerging markets. Because of institutional voids, emerging market companies often cannot access risk capital and experienced research talent in their home markets. As a result, it is difficult for them to invest large sums in, for example, research and development—an investment that is critical if these companies are to compete effectively against global giants. In some emerging markets such as Brazil, India, or Russia, emerging market companies are also hampered by creaky domestic infrastructure and unreliable quality in their supply network. Even when emerging market-based firms are able to circumvent some of these hurdles and put themselves on a trajectory of rapid growth, they can be stymied by the shallow pool of domestic management talent.

Emerging market-based companies that choose to take on multinationals can potentially turn the disadvantage of operating in an emerging market into an advantage, or at least blunt multinationals’ incumbency advantages of brand name and access to capital and technology. First, emerging market entrepreneurs have an advantage over foreign multinationals in dealing with local institutional voids because of their experience and cultural familiarity in dealing with these voids. Institutional voids hurt all firms operating in markets rife with them, but local firms often are better able to work around them.

Prospective emerging giants can exploit this relative advantage. Spoiled by their years of experience in environments having a well-developed institutional infrastructure, often multinational managers are ill equipped to deal with the institutional voids that make it difficult to access reliable market information or structure business partnerships based on reliable contracts.

Responding to Institutional Voids

Prospective emerging giants face a set of strategic choices to respond to institutional voids that mirror the choices faced by multinationals. Because of their home location and unique capabilities, however, emerging market-based companies have different options to respond (see table 5-1).

Replicate or Adapt?

Many emerging market-based companies have looked to developed market-based multinationals as exemplars and have attempted to replicate their models. But often, simply replicating these models does not work. Companies that literally replicate business models developed in foreign contexts often end up paving the way for incoming multinationals from those foreign markets, which can then enter the market with more resources and worldwide economies of scale. Instead, success for emerging market-based companies is rooted in devising and implementing strategies that leverage their understanding of the local context, that find creative solutions to the challenges of undeveloped hard and soft infrastructure, and that use these solutions to blunt the edge of incumbent multinationals—in brief, adapting through local knowledge.

TABLE 5-1

Responding to institutional voids in emerging markets

| Strategic choice | Options for emerging market-based companies |

|---|---|

Replicate or adapt? |

|

Compete alone or collaborate? |

|

Accept or attempt to change market context? |

|

Enter, wait, or exit? |

|

As described in chapter 4, adaptation is a difficult process, and multinational companies often are unable or unwilling to tailor their business models and strategies to the institutional context and local tastes of each developing market in which they operate. Local companies can often access and exploit diffuse local knowledge to tailor their offerings and operations to a much greater extent than multinationals.

Multinationals’ incumbency advantages can be a disadvantage in localization because they might be particularly reluctant to modify brands, organizational cultures, and cost structures that were designed to derive strength from their global uniformity. Often less constricted by preexisting cost structures and organizational processes than developed market-based multinationals, local companies can often more nimbly incorporate local knowledge into their business models. Without adaptation, multinationals often have trouble reaching beyond the global market segment, as noted in chapter 4. Exploiting their relative advantage in local adaptation can enable emerging market-based companies to target the emerging middle class seeking global quality products and services with pared down features at local prices, the traditional segments that accept local quality at very low cost, and bottom-of-the-market segments that are looking for goods and services at extremely low cost.

Although replication is not a viable option for prospective emerging giants, these companies need to decide how to adapt their business models to the context of their home markets by exploiting local knowledge of product and factor markets. Product market knowledge is fundamentally about what goods local consumers need or want and how to produce and deliver them. Not surprisingly, consumers in emerging markets— particularly large markets with diverse populations and geographies— have localized preferences and unique needs. Indigenous companies can offer value by knowing local customers better and meeting their needs with desirable, affordable products through adaptation. This local knowledge is a substitute for market research and other intermediaries that are missing in emerging markets.

Some fast food companies in developing countries, for example, have built defensible businesses by understanding local tastes and providing more palatable menu selections than those offered by foreign competitors. Jollibee Foods in the Philippines emerged from the recognition that Filipinos liked their burgers to have a particular taste. Nando’s started in South Africa by providing convenient cooked chicken that suited the local palate. Similarly, Pollo Campero, originating in Guatemala, has won domestic market share by providing locally palatable roast chicken.

These companies have done battle with larger multinationals and, to varying extents, have emerged victorious. Further, they have used their mastery of the unique tastes of their domestic market customers to expand globally. Jollibee Foods caters to the tastes of Filipino communities worldwide, Nando’s can be seen in the United Kingdom and Malaysia (among other locations), and Pollo Campero has achieved growth throughout the Americas by targeting Latino communities in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Peru, and Mexico as well as parts of the United States.

Domestic companies can also exploit their familiarity and experience with local product market infrastructure, such as unique distribution channels and logistics networks, that prevail in the absence of developed market infrastructure. The peculiarities of local product market infrastructure can be significant barriers to new competitors. Even if companies are able to introduce a product that consumers want, reaching them can be cost prohibitive and a business deterrent for foreign-based firms. South African Breweries (now SABMiller), for example, exploited its product market knowledge to build an efficient distribution system that could reach South Africa’s traditional beer-drinking outlets—called shebeens, or backyard bars—and entrench its brand among local consumers. Developing this system would have been a difficult proposition for a multinational such as Heineken or Anheuser-Busch. Later in this chapter, we look at the ways in which India-based Tata Motors has exploited product market knowledge to adapt its business model in light of institutional voids.

Factor market knowledge is an understanding of the labor and supply chain inputs that enable companies to create products or services for the marketplace. Emerging market-based companies can exploit their superior ability to identify and manage local talent and resources or their experience with local supply chains to serve local as well as global customers.

Emerging markets boast high-quality talent and production resources, often at significantly cheaper rates than similar talent and resources in developed markets. Given the institutional voids in emerging markets, however, it can be difficult and costly for companies from developed markets to access talent and resources. Multinationals often have trouble sorting talent in markets where personnel quality and the reputations of educational institutions vary widely and where work experience and training may differ substantially from that available in developed markets. From a supply chain perspective, operating and managing remote sourcing and delivery services in regions with relatively poor infrastructure pose additional challenges to foreign companies.

Emerging market-based companies can leverage their expertise in factor markets in a number of ways. Later in this chapter, we look at how Cosan has successfully exploited its knowledge of factor markets in Brazil’s sugar and ethanol sector.

Compete Alone or Collaborate?

Multinationals entering their home markets are powerful competitors, but they can also be valuable partners for prospective

emerging giants. Emerging market-based companies face a choice parallel to the one faced by multinationals: compete alone

or collaborate? Because many multinationals are required to collaborate with local firms when they enter emerging markets,

collaboration is often more of a strategic choice for emerging market-based companies. Collaboration can help prospective

emerging giants acquire new capabilities from developed markets and add credibility to their organizations, and that can be

particularly valuable in light of institutional voids that challenge their ability to do so on their own. We look at how two

emerging giants—Do![]() u

u![]() Group of Turkey and Bharti Airtel of India—approached their choices to collaborate with foreign partners.

Group of Turkey and Bharti Airtel of India—approached their choices to collaborate with foreign partners.

Accept or Attempt to Change Market Context?

Beyond adapting to voids, prospective emerging giants are often compelled to invest in developing market infrastructure to fill voids. Filling voids can be a powerful source of competitive advantage, because foreign-based multinationals are often less willing to invest in the expensive proposition of changing the market context.2 Chinese white goods firm Haier developed into a powerful brand in its home market by filling a number of institutional voids, as we discuss later in this chapter.

Enter, Wait, or Exit?

Developed market-based multinationals have clear exit options from emerging markets. These firms have the luxury of choosing among any number of markets in which to invest—and the resources to cover the cost of mistakes. Emphasizing opportunities elsewhere is a much more difficult option for entrepreneurs and domestic companies in emerging markets. Nonetheless, exiting early is an option for companies with mismatched and unrewarded capabilities that they cannot exploit amid the institutional voids of their home markets.

Emerging Giants Competing at Home: Examples

In the rest of this chapter, we look at examples of emerging giants that confronted these strategic choices in the face of institutional voids in their home markets (see table 5-2). As in chapter 4, even though each of these companies has confronted each of these strategic choices, we focus on the most salient choice for each example. Many emerging giants have organized themselves as business groups to help confront these choices in light of institutional voids. We consider the benefits and costs of business group organizations for emerging market-based firms at the end of this chapter.

TABLE 5-2

Case examples

| Strategic choice | Examples |

|---|---|

Replicate or adapt? |

Tata Motors in India Cosan in Brazil |

Compete alone or collaborate? |

Do |

Accept or attempt to change market context? |

Haier in China |

Enter, wait, or exit? |

Software firms in India |

Replicate or Adapt? Tata Motors

Tata Motors—part of India’s Tata Group, one of the most successful emerging market-based business groups—has carefully adapted its offerings and organization based on institutional voids, particularly with the development of a new vehicle, the Ace.3 By 2005, Tata Motors had become India’s largest commercial truck maker but found itself squeezed amid growing foreign competition in its home market. At the top end of the market, major foreign truck manufacturers, such as Volvo, were challenging Tata Motors’ supremacy in large trucks. Producers of pickup trucks from Japan, Korea, and other countries, meanwhile, were competing against Tata Motors’ smaller commercial vehicles. The low end of India’s commercial vehicle market was dominated by three-wheelers made by domestic and foreign companies.

Tata Motors responded to this competitive challenge by exploiting product market knowledge and adapting business processes with the development of the Ace, a four-wheeled mini-truck, to target a niche in the marketplace. The vehicle opened a new segment for Tata Motors, helping the company reduce the risk of dependence on its main commercial truck business, which was highly cyclical.

The Ace was designed in response to market conditions in India and an unmet consumer need identified by Tata Motors. Three-wheeled vehicles were pervasive as commercial vehicles in India, used to ferry produce and merchandise to rural markets and deliver goods in urban centers, some of which limited access to larger commercial trucks to ease congestion. Despite their low price and nimbleness, however, three-wheelers were unsafe, slow, and frequently overloaded. Reliance on the vehicles often resulted in damaged goods and delayed deliveries. Moreover, three-wheelers were barred from operating on India’s “golden quadrilateral,” the new expressway network that linked the country’s largest cities.

The Ace was positioned as a replacement for three-wheelers. It had a comparable payload size and price point but offered many of the benefits of larger light commercial vehicles to serve the “last mile” of distribution in India’s congested cities. The truck was designed to be the only vehicle in India allowed on all roads. Although the initial cost of the Ace—about $5,000—was higher than that of three-wheelers, the truck was designed to be more economical after accounting for its larger payload capacity and fuel costs. Tata Motors designed the Ace to meet higher safety standards than existing requirements and norms in India. The move put Tata Motors in a stronger position than competitors if higher standards were adopted by Indian regulators and would also facilitate the vehicle’s entry into international markets having higher standards already on the books.

The Ace was unique not only in its concept but also in the ways in which Tata Motors adapted the execution of the project to meet the vehicle’s target price point and reach its target customers. Tata Motors conducted extensive market research through interviews with potential customers to identify their needs and constraints, helping the company refine the Ace’s design, pricing, and features—and substituting for absent market research intermediaries. The company looked at the product through the eyes of its customers, incorporating, for example, realistic expectations about overloading, a common practice in poor, populous countries.

Meeting the project’s tight budget—to enable the Ace to be positioned at such a low price point—forced Tata Motors to be innovative in product development and procurement. The company employed a cross-functional team for product development and adopted a Japanese-style production preparation process (3P), which incorporated suppliers and other stakeholders earlier in the development process. Aggregate outsourcing, e-sourcing, and the use of existing production facilities also helped lower costs.

Because it blurred the lines of existing product segments, successfully introducing the Ace required Tata Motors to educate the marketplace. After listening to customer guidance through the product development process, the company needed to invest in customer education to stoke demand for the Ace, particularly because of the truck’s operating economics. To ease concerns about the Ace’s high initial cost, the company offered financing through its consumer finance arm. This action filled a void, because auto financing was a relatively new practice in India—and almost unknown among customers in the Ace’s target market.

Tata Motors also adapted its distribution and after-sales service operations for the Ace to meet the needs of the vehicle’s target customers. Many of the Ace’s cost-conscious potential customers in rural areas might not be willing to travel long distances to see the vehicle, so the company deployed a new bare-bones dealership format that would bring the Ace closer to these customers without incurring the expense of a new network of full-service dealerships. Similarly, instead of building an expensive new network of service centers, the company trained local mechanics and gave them tools to take care of common problems. Vehicles would be sent to larger urban service centers only in the event of major repairs or accidents.

Less than a year after the Ace’s introduction in May 2005, Tata Motors had already sold thirty thousand units even though the vehicle was available in only one-quarter of the country. A survey of Ace purchasers found that more than half were buying their first commercial vehicle, suggesting that the product had expanded the existing commercial vehicle market. “It is no more a niche product,” said one company executive. “It has created a category by itself. What we are trying to create through this is . . . businessmen and entrepreneurs, who will come into the transportation business. That is the key driver of demand creation that we are looking at.”4

Because demand surpassed the capacity of the existing plant where the Ace was initially produced, Tata Motors established a new plant in northern India to produce the Ace and related vehicles with a capacity of 250,000 vehicles. The company also introduced the vehicle in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh, with an eye to introducing the Ace in still other developing markets. Similarly, Tata Motors exploited local knowledge to target a difficult market segment with the development of the Nano, a $2,500 “people’s car” introduced in 2008.

Tata Motors successfully exploited local knowledge in conceptualizing the Ace and adapted to institutional voids to deliver the product (see table 5-3). However, the company’s market opportunity with this product was closely tied to the state of India’s infrastructure at the time of its introduction. The company’s success with the Ace soon attracted other companies—both foreign and domestic—to develop similar vehicles for India. By filling the void of India’s underdeveloped market research intermediaries for its own product development, Tata Motors served as a market researcher for its competition.

TABLE 5-3

Tata Motors in India: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

Can companies easily obtain reliable data on customer tastes and purchase behaviors? Are there cultural barriers to market research? Do world-class market research firms operate in this country? |

Underdeveloped sector of market research providers (product market information analyzers and advisers) |

Adapted: Interviewed potential customers internally and incorporated results into Ace design and pricing |

Do large retail chains exist in the country? If so, do they cover the entire country or only the major cities? Do they reach all consumers or only wealthy ones? How strong are the logistics and transportation infrastructures? |

Underdeveloped dealer networks (product market aggregators and distributors); difficult for rural customers to travel to dealerships in urban centers (hard infrastructure) |

Adapted: Established basic dealerships to bring Ace “showroom” closer to rural customers unwilling or unable to travel to cities to see Ace models |

Are consumers willing to try new products and services? Do they trust goods from local companies? How about foreign companies? |

Underdeveloped consumer information providers (product market information analyzers and advisers) |

Adapted: Invested in customer education to show value proposition of the Ace |

Do consumers use credit cards, or does cash dominate transactions? Can consumers get credit to make purchases? Is data on customer creditworthiness available? |

Limited sources of capital for target customers (product market transaction facilitators) |

Adapted: Offered financing for Ace through consumer finance arm |

How do companies deliver after-sales service to consumers? Is it possible to set up a nationwide service network? |

Underdeveloped vehicle service network (product market aggregators and distributors) |

Adapted: Trained and provided tools to local mechanics for common problems |

Importantly, however, Tata Motors has a head start in the segment, and, perhaps more critically, execution was critical to the success of the Ace. The company’s innovative procurement process and investments in developing the ecosystem for the vehicle through its distribution and service operations could help Tata Motors sustain competitive advantage.

Replicate or Adapt? Cosan

Cosan has exploited its ability to adapt to the institutional voids in the factor markets of Brazil to emerge as one of the world’s leading sugar and ethanol producers. The Brazilian government had closely regulated prices, production, and purchase of sugar and ethanol, but after deregulation in the 1990s, the industry took off, enabling companies such as Cosan to exploit the country’s inherent advantages in sugar and ethanol production conferred by its climate and soil.5

Cosan emerged from a competitive landscape in Brazil dominated by small and inefficient family-run businesses, particularly in the 1980s before deregulation.6 The company had grown in the fragmented sugar and ethanol sectors mostly through acquisitions—particularly after deregulation—increasing its production efficiency through economies of scale.7 With a 9 percent share of Brazil’s sugar market and 7 percent of its ethanol market, Cosan was the country’s largest producer of both as of June 2009.8 (As of December 2007, Cosan’s next-largest rival held a 4.3 percent share and others held shares of around 2 percent.)9

In 2007, Cosan raised more than $1 billion in an initial public offering (IPO) on the New York Stock Exchange, the first Brazilian biofuel firm to do so.10 The company planned to use the proceeds of the public offering to continue expanding through acquisitions and some green-field projects.11 “The message they are giving now is they want to be consolidators, not acquired,” said one stock analyst.12

More recently, foreign-based multinationals have been eager to tap in to the opportunities of Brazil’s growing biofuel sector.13 The attractiveness of the sector to large multinationals compelled Cosan to restructure its corporate organization to prevent an unwanted takeover, enabling founder Rubens Ometto Silveira Mello to maintain control of the company. “If he gave up voting control, boom, they would get taken out,” one stock analyst said.14 Cosan saw some benefits from the entry of large multinationals in consolidating the sector. As one company executive noted, “We have 350 players in Brazil. It would be better to have 20 of those companies expanding in the market because the discipline of those guys is so much better.”15

Operational know-how and a willingness to invest in systems surrounding its production facilities were critical for Cosan to differentiate itself from its local and incoming foreign competition. “We manage the society around the mill, which is key,” said one company executive. “We are an agricultural business. We plant, we fertilise, we raise cane, we cut cane, we operate the plants, we do everything. These major agribusinesses, they don’t do agriculture. They buy and sell supplies.”16 Most of the institutional voids in Cosan’s business remain upstream, so these capabilities have been persistent sources of competitive advantage vis-àvis foreign agribusiness giants and oil companies targeting the biofuel market.

Cosan saw its investments in agricultural research and its use of technology to manage operations as other key sources of competitive advantage.17 Through sophisticated monitoring of crops, production, and soil quality and process improvements such as in sugarcane washing, Cosan sought to maximize the efficiency of its operations. The company was able to bring these efficiency gains to the mills it acquired. Cosan increased production capacity at Da Barra from 79 tons of sugarcane at the time of acquisition in August 2002 to 894 tons in 2008–2009.18 Cosan’s expertise at managing acquisitions—developed amid myriad institutional voids immediately after deregulation—have remained a key source of competitive advantage for the company.

A large share of sugarcane production in Brazil relied on contracted labor to cut the sugarcane by hand. Working conditions for these laborers had been a frequent source of criticism. In 2007, Cosan became the largest producer—and among the first—to agree to eliminate outsourced labor in response to these concerns.19

In addition to acquisitions, Cosan pursued brownfield projects in the productive but competitively crowded São Paulo region, and greenfield developments inland. “[W]e need a place without sugar mills,” one company executive explained, “a place where we can develop sugarcane fields surrounding the plants, to create clusters that act as a system. Having mills in a cluster reduces the cost of transportation to the mills and reduces the energy consumption.”20

Some 85 percent of Brazil’s ethanol production was sold through five distributors, giving these firms strong bargaining power.21 Ethanol producers also bore the costs of transporting fuel from their facilities to distribution centers and then back to retail chains for final distribution.22 As a result, Cosan sought to become the country’s first integrated ethanol company.23 Cosan bought a chain of fifteen hundred Esso filling stations from Exxon in 2008, making it the first major producer to move into retail distribution.24 “We wanted to secure our access to consumers, and this deal gave us the necessary scale,” said one company executive.25

The deal came as many major oil companies sought to move upstream into biofuel production.26 Cosan saw its local knowledge and experience as key competitive advantages vis-à-vis incoming foreign multinationals. “[Y]ou have to deal with workers, unions, climate conditions, judges, cities and priests,” one company executive said. “That is not very easy for any company to do, and it’s an expertise that you have to develop over time. As a Brazilian, I can understand the culture better than an American or European. If I come to Europe to buy a wheat mill, it won’t be easy either. I have to deal with the French Union that have a strong lobby. It requires experience.”27 Cosan’s growth and development in Brazil illustrate how emerging market-based companies can exploit their ability to navigate factor markets to build competitive advantage against both local and foreign competition (see table 5-4).

Prospective emerging giants often face the question of whether to collaborate with multinationals or to compete against them

alone. As we discuss next, Bharti Airtel of India and Turkey’s Do![]() u

u![]() Group pursued collaborations with foreign firms at different stages of their corporate histories. Their foreign partners provided capital, operational capabilities, strategic advice, and valuable connections

to other global resources. The two companies sought partners that would also improve and signal the credibility of their organizations.

Group pursued collaborations with foreign firms at different stages of their corporate histories. Their foreign partners provided capital, operational capabilities, strategic advice, and valuable connections

to other global resources. The two companies sought partners that would also improve and signal the credibility of their organizations.

TABLE 5-4

Cosan in Brazil: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

Can companies access raw materials and components of good quality? Is there a deep network of suppliers? Are there firms that assess suppliers’ quality and reliability? Can companies enforce contracts with suppliers? |

Limited ability to sort suppliers (factor market information analyzers and advisers; credibility enhancers) |

Adapted: Invested in quality through technology and process improvements, and scale through acquisitions to differentiate business in fragmented sector |

How strong are the logistics and transportation infrastructures? Have global logistics companies set up local operations? |

Underdeveloped logistics and transportation infrastructure (product market aggregators and distributors) |

Adapted: Sought to build out fully integrated operations |

How are the rights of workers protected? If a company were to adopt its local rivals’ or suppliers’ business practices, such as the use of child labor, would that tarnish its image overseas? |

Poor labor conditions in sugarcane production (labor market regulators and other public institutions) |

Adapted: Signed contract to eliminate outsourced labor |

Compete Alone or Collaborate? Bharti Airtel in India

Established as a start-up by entrepreneur Sunil Mittal and with more than $5 million in annual sales by 1992, Bharti Airtel grew into one of India’s largest telecommunications providers, with a market capitalization of $31.8 billion by 2008.28 The company’s partnerships with a range of foreign firms over the course of its history were central to Bharti Airtel’s ability to grow in a capital-intensive industry and take on tough competition from state-owned enterprises and well-funded offshoots of powerful business groups. Foreign partners helped Bharti Airtel in its first bid for a cellular service license, and major equity investments by Singapore Telecom (SingTel) and U.S.-based private equity investor Warburg Pincus fueled the company’s growth through acquisitions.

Bharti partnered first with Compagnie Générale des Eaux of France, Mauritian cell operator Emtel, and Mobile Systems International of the United Kingdom in a successful joint bid for India’s first cellular service license. Soon after Bharti launched cellular service in Delhi in September 1995, it faced competition from Sterling Cellular, which was controlled by Indian steel giant Essar.

Bharti quickly learned how to compete against rivals having more resources. The company targeted small business owners and retail customers instead of the corporate market, where larger business groups would have an advantage. Although business group organizations can bring advantages to emerging market-based firms—as we discuss later in this chapter—Bharti exploited its focus. As a company executive noted, “We were lucky not to carry the baggage other players had of their existing businesses. I was often told this was a disadvantage, as I did not have the same resources as they. As you can see, that has been proved wrong. Often there were very strong temptations to start other businesses—we almost started an airline at one point. But every time we braced ourselves and said no. Today our focus has been our greatest asset.”29 (Bharti Enterprises, organized as a business group, later entered the retail, life insurance, and other sectors in India.)

Italian state-owned telecom operator STET invested $58 million in Bharti in 1996, and, from 1997 through 1999, British Telecom (BT) made $250 million in equity investments.30 BT also helped Bharti improve its operations by providing assistance in corporate communication, lending technology support, and extending procurement benefits to Bharti through its own vendor network. Importantly, Bharti maintained management control in the partnership. “Despite its size, our partnership is one of equals and the inputs which we receive are tremendous,” noted a Bharti executive.31

In 1995, a second tranche of cellular service licenses came up for auction, but Bharti did not bid high enough for the desirable locations. The Winning in Emerging Markets winning bids turned out to be too high and unsustainable for some new entrants. Bharti wanted to expand through acquisitions, but it needed more capital. In 1999, Warburg Pincus purchased a 20 percent stake in Bharti for $60 million. The following year SingTel invested $400 million, and in 2001, Warburg Pincus and SingTel each invested an additional $200 million. Bharti received smaller investments from New York Life Insurance, Asian Infrastructure Fund Group, and International Finance Corporation.

Bharti was still a relatively small operation when it attracted these major investments. As the only profitable cellular service provider in a market tipped for stunning growth, Bharti presented investors with significant upside potential. An executive at Warburg Pincus also noted the quality of the company’s management and the strength of its consumer-focused model compared with those of its competition:

We were willing to bet big on Bharti because we saw the right strategy, the right team and the right focus. We were impressed by Sunil Mittal’s vision, his deep domain expertise, and the quality of his management team. In spite of his accomplishments, we saw a man who was willing to learn, to listen, and to change—he does not pretend that he knows it all. It is not easy to find these qualities in an entrepreneur. Our business is about backing people, and Bharti is a very good example of this strategy.32

Partnering with investors such as Warburg Pincus and SingTel offered Bharti more than just capital. The business groups with which some of Bharti’s toughest competitors were affiliated had access to capital, political support, and deeper wells of management talent, as well as valuable reputations. Investments from global players offered signals of credibility that helped Bharti neutralize some of these advantages.

Warburg Pincus and SingTel offered other resources and advice that helped Bharti build its business. Three representatives of SingTel and two Warburg Pincus partners sat on Bharti’s thirteen-person board. Bharti and SingTel jointly built an underwater cable network linking Bharti’s domestic voice and data network to SingTel’s global network. Warburg Pincus offered significant strategic advice on Bharti’s geographic expansion, acquisition approach, financing, and operations. “Warburg Pincus let us think big,” said a Bharti executive.33 Warburg Pincus helped persuade Bharti to acquire existing operations—even those not fully meeting the company’s high standards—and to look beyond northern India to craft a pan-India strategy to tap in to opportunities in the wealthier south.

Bharti went public in 2002, listing 10 percent of its shares on the National Stock Exchange, and subsequently has raised capital through loans and other facilities. By 2005, Warburg Pincus had earned $1.1 billion by selling two-thirds of its stake in Bharti—“one of the very best deals in the firm’s history,” according to a Warburg Pincus executive.34

Bharti’s early foreign partnerships helped nurture its growth with much-needed capital, resources, and strategic advice. Risk capital is important to the development of any young company. Bharti’s partnerships were particularly valuable because of the institutional voids in its home market and the deeper expertise and richer resources—such as the connection to SingTel’s global network—it gained from foreign partners than would be possible to access locally (see table 5-5). These capabilities and resources helped Bharti combat the inherent advantages of state-owned and business group-affiliated rivals and grow into one of India’s largest telecom service providers. These foreign partnerships signaled credibility to the outside world, but accessing them required Bharti to demonstrate not only a highly promising business model and successful track record but also credibility in its management and corporate governance—a lesson for any emerging market-based firm looking for help from overseas.

Compete Alone or Collaborate? Do u

u Group in Turkey

Group in Turkey

In 2005, Do![]() u

u![]() Group, one of Turkey’s largest business groups, sought out a foreign partner to improve the competitiveness

and capabilities of its flagship financial services company, Garanti Bank.35 Do

Group, one of Turkey’s largest business groups, sought out a foreign partner to improve the competitiveness

and capabilities of its flagship financial services company, Garanti Bank.35 Do![]() u

u![]() Group had restructured itself in the early 2000s in response to economic crisis in its home market and incoming foreign competition. As part of the restructuring, the group streamlined its portfolio

and worked to institutionalize standards across the fairly autonomous group operating companies.

Group had restructured itself in the early 2000s in response to economic crisis in its home market and incoming foreign competition. As part of the restructuring, the group streamlined its portfolio

and worked to institutionalize standards across the fairly autonomous group operating companies.

TABLE 5-5

Bharti Airtel in India: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

Does a venture capital industry exist? If so, does it allow individuals with good ideas to raise funds? Can companies raise large amounts of capital in the stock market? Is there a market for corporate debt? |

Underdeveloped capital-providing intermediaries (capital market aggregators and distributors; transaction facilitators) |

Collaborated: Sought out foreign partners for capital (as well as access to global resources and strategic advice) |

Are consumers willing to try new products and services? Do they trust goods from local companies? How about foreign companies? |

Underdeveloped consumer information providers (product market information analyzers and advisers) |

Collaborated: Foreign partners helped build credibility for customers who might have opted for the reassurance of a business group brand name |

Do independent financial analysts, ratings agencies, and the media offer unbiased information on companies? How effective are corporate governance norms and standards in protecting shareholder interests? |

Underdeveloped capital market information providers and certifiers (capital market information analyzers and advisers; credibility enhancers) |

Collaborated: Foreign partnerships helped build credibility for future investors when IPO was issued |

Garanti Bank exemplified the restructured group’s concentration on consumer- and marketing-focused businesses. Garanti had developed a strong brand and was a leader among Turkish banks in incorporating IT into its financial services offerings. By the time Garanti considered an international partnership in 2005, the bank had more than $20 billion in assets and was Turkey’s third-largest private bank.36 Foreign banks had a small but growing presence in Turkey at the time. As of June 2004, foreign-owned banks accounted for a 2.6 percent market share in assets, 4.1 percent of loans, and 2.5 percent of deposits.37 In early 2005, BNP Paribas of France and Fortis of Belgium separately bought stakes in Turkish banks.38

Do![]() u

u![]() sought out a foreign partner for Garanti for a number of reasons. The company hoped to reduce the debt on Garanti’s

balance sheet, join with a foreign entity to expand its business in the region, and institutionalize corporate governance

and other best practices. This latter advantage of a partnership could bring to Do

sought out a foreign partner for Garanti for a number of reasons. The company hoped to reduce the debt on Garanti’s

balance sheet, join with a foreign entity to expand its business in the region, and institutionalize corporate governance

and other best practices. This latter advantage of a partnership could bring to Do![]() u

u![]() operational know-how, such as lean

management, and also enable the group to broach sensitive issues as the family business restructured itself, as a group executive

noted: “Sometimes when you have a third party or a new shareholder, until that day, things that you couldn’t converse or you

couldn’t discuss, now you can talk about this easier. In the family businesses in emerging markets, when the businesses are

growing, the family, the owner, and the management become too much like the family and so any criticism or saying no is taken

very much as a personal thing.”39

operational know-how, such as lean

management, and also enable the group to broach sensitive issues as the family business restructured itself, as a group executive

noted: “Sometimes when you have a third party or a new shareholder, until that day, things that you couldn’t converse or you

couldn’t discuss, now you can talk about this easier. In the family businesses in emerging markets, when the businesses are

growing, the family, the owner, and the management become too much like the family and so any criticism or saying no is taken

very much as a personal thing.”39

However, while adding these capabilities Do![]() u

u![]() did not want to jeopardize its existing sources of competitive advantage,

particularly Garanti’s brand and a corporate culture of innovation and fast decision making. “Everybody was wondering what

would be life after such a partnership. We had to convince them,” said a group executive. “I didn’t want to lose the culture

of the institution.”40 The company also hoped to motivate employees through training and career development opportunities offered by a foreign partner.

did not want to jeopardize its existing sources of competitive advantage,

particularly Garanti’s brand and a corporate culture of innovation and fast decision making. “Everybody was wondering what

would be life after such a partnership. We had to convince them,” said a group executive. “I didn’t want to lose the culture

of the institution.”40 The company also hoped to motivate employees through training and career development opportunities offered by a foreign partner.

Do![]() u

u![]() considered offers from multinational banks but ultimately partnered with GE Consumer Finance in an equal partnership.

(Do

considered offers from multinational banks but ultimately partnered with GE Consumer Finance in an equal partnership.

(Do![]() u

u![]() sold a 25.5 percent stake in Garanti to GE, half of the Do

sold a 25.5 percent stake in Garanti to GE, half of the Do![]() u

u![]() holding in the bank.) The international banks that

bid for stakes wanted to acquire majority holdings in Garanti and rebrand the bank.41 “What they will do is simple,” said a group executive. “They will put down the Garanti sign and they put up their sign .

. . It’s great that these guys have great programs all around the world, but those programs are one-size-fits-all programs.”42

holding in the bank.) The international banks that

bid for stakes wanted to acquire majority holdings in Garanti and rebrand the bank.41 “What they will do is simple,” said a group executive. “They will put down the Garanti sign and they put up their sign .

. . It’s great that these guys have great programs all around the world, but those programs are one-size-fits-all programs.”42

GE’s bid was not the highest of the partnership contenders, but the organization offered other benefits to Garanti and Do![]() u

u![]() Group.43 Because GE was not a bank, it would bring a different perspective to board discussions and would look at Garanti differently than would a multinational bank. “In a board, if you had a partnership

with XYZ multinational bank, I think there will be nothing to talk about but the profitability,” a group executive said.44

Group.43 Because GE was not a bank, it would bring a different perspective to board discussions and would look at Garanti differently than would a multinational bank. “In a board, if you had a partnership

with XYZ multinational bank, I think there will be nothing to talk about but the profitability,” a group executive said.44

As a diversified multinational, GE also offered Do![]() u

u![]() the possibility of further cooperation in other sectors.45 Do

the possibility of further cooperation in other sectors.45 Do![]() u

u![]() had already partnered with GE’s CNBC television network in Turkey starting in 1998, and with GE Real Estate in a joint

venture in 2006. Because GE was not a full-service financial institution, however, the partnership would give Do

had already partnered with GE’s CNBC television network in Turkey starting in 1998, and with GE Real Estate in a joint

venture in 2006. Because GE was not a full-service financial institution, however, the partnership would give Do![]() u

u![]() flexibility

to partner with different companies in other financial services; a group executive likened the deal to buying an individual

vitamin at GNC with the possibility of buying others, instead of a single multivitamin.46

flexibility

to partner with different companies in other financial services; a group executive likened the deal to buying an individual

vitamin at GNC with the possibility of buying others, instead of a single multivitamin.46

Since selling the stake to GE, Garanti has pursued regional growth in Romania while looking to expand in Ukraine, and the

partners have transferred capabilities to each other. “The day after the relationship started, GE saw a lot more value that

they did not see on the paper before,” a group executive said. Examples of this value included Garanti’s technology, branding

and marketing of credit cards, success with alternative distribution channels, and use of customer data to offer products

through tellers.47 The Garanti executive who spearheaded the merger of the three Do![]() u

u![]() -owned banks into Garanti has also transferred to GE

as the company’s head of operations for Europe.48 Garanti has sent employees to GE training facilities and learned operational capabilities from its partner. “We are now utilizing

lean management, six sigma stuff. We already started getting results,” said a group executive. “So maybe in certain things

we do not need the McKinseys of this world any more. We are taking it from our partner—with zero fee.”49

-owned banks into Garanti has also transferred to GE

as the company’s head of operations for Europe.48 Garanti has sent employees to GE training facilities and learned operational capabilities from its partner. “We are now utilizing

lean management, six sigma stuff. We already started getting results,” said a group executive. “So maybe in certain things

we do not need the McKinseys of this world any more. We are taking it from our partner—with zero fee.”49

Do![]() u

u![]() Group approached collaboration with a clear view of what it wanted from its partner. The company sought to preserve

Garanti’s brand—a valuable property in a market that lacked sophisticated product market information analyzers and advisers—but

hoped to use the partnership to compensate for other institutional voids in its home market (see table 5-6). Just as prospective

emerging giants—like any company operating in an emerging market—need to match their capabilities to their home market contexts, these firms need to align their collaborations with the missing capabilities that could help

them become more competitive in those contexts.

Group approached collaboration with a clear view of what it wanted from its partner. The company sought to preserve

Garanti’s brand—a valuable property in a market that lacked sophisticated product market information analyzers and advisers—but

hoped to use the partnership to compensate for other institutional voids in its home market (see table 5-6). Just as prospective

emerging giants—like any company operating in an emerging market—need to match their capabilities to their home market contexts, these firms need to align their collaborations with the missing capabilities that could help

them become more competitive in those contexts.

TABLE 5-6

Do![]() u

u![]() Group in Turkey: Responding to institutional voids

Group in Turkey: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

Are consumers willing to try new products and services? Do they trust goods from local companies? How about foreign companies? |

Underdeveloped consumer information providers (product market information analyzers and advisers) |

Competed alone: Kept valuable brand, even within foreign partnership |

How strong is the country’s education infrastructure, especially for technical and management training? |

Underdeveloped educational and training intermediaries (labor market aggregators and distributors) |

Collaborated: Exploited opportunities for training exchanges with foreign partner |

How effective are corporate governance norms and standards in protecting shareholder interests? |

Underdeveloped corporate governance standards (capital market credibility enhancers) |

Collaborated: Used foreign partnership to bring institutional best practices to restructuring family-owned company |

Are corporate boards independent and empowered, and do they have independent directors? |

Shallow pool of qualified independent directors (capital market information analyzers and advisers) |

Collaborated: Sought out foreign partner that could provide strategic advice through seats on board |

Accept or Attempt to Change Market Context? Haier in China

In the face of serious institutional voids, adaptation and collaboration are not enough for many prospective emerging giants.50 Unwilling to accept the limitations on growth and corporate development imposed by institutional voids, these companies can work actively to fill these voids. Haier Group of China emerged as a globally competitive producer of household appliances by successfully exploiting product market knowledge and navigating the context of its home market by filling voids, particularly in distribution and service.

In December 1984, Haier—then named Qingdao Refrigerator Factory—was a debt-laden operation several months behind in paying its employees’ salaries. At the time, only 6.6 percent of China’s urban households had refrigerators, and the factory was one of China’s three hundred refrigerator producers, most of whose products exhibited low standards of quality.51 Despite robustly growing market demand for refrigerators as living standards improved in China, Haier resisted mass production and instead focused on quality and brand building—a valuable strategy in a market that lacked well-developed independent credibility-enhancing intermediaries.

By 2004, Haier dominated its home market with about a 30 percent share of China’s white goods market and a growing presence in “black goods” sectors, such as televisions and personal computers. Amid industry consolidation, price wars, and the entry of powerful foreign brands, Haier built and sustained competitive advantage through innovative and rapid response to customer tastes and needs, by filling voids in after-sales service, and by employing efficient distribution.

Compared with foreign and domestic rivals, Haier was particularly responsive to market demands and was willing to offer differentiated products to meet customer needs. The company had some ninety-six product categories and 15,100 specifications, as a result of small feature innovations and tailored products that were inexpensive to produce— when incorporated modularly—and were highly valued by customers.

When a customer in a rural area of China’s Sichuan province complained to Haier that his washing machine was breaking down, service technicians found the plumbing clogged with mud. Rural Chinese were using the Haier machines—designed to wash clothing—to clean sweet potatoes and other vegetables. Haier engineers then modified the washer design to accommodate this use. Since then, Haier washing machines sold in Sichuan have included a new label: “Mainly for washing clothes, sweet potatoes and peanuts.”52

To accommodate summer lifestyles requiring frequent changes of clothing, Haier created a tiny washing machine that cleaned a single change of clothes. The model used less electricity and water than larger machines, making it an instant hit in Shanghai. Similarly, the company designed small refrigerators for urban households where space is at a premium. Haier’s adaptation through market responsiveness was particularly valuable against foreign competition, which was less attuned to consumer preferences in a market that lacked sophisticated market research intermediaries.

Most critical to Haier’s success in building a highly competitive business in its home market were the company’s attempts to change the market context by filling institutional voids. In after-sales service, Haier established a service center in Qingdao in 1990 that featured a computerized system to track tens of thousands of customers.53 By 2004, the company had a service network of fifty-five hundred independent contractors—one for each sales outlet—who made house calls from requests to a nationwide hotline. The company even provided temporary replacements for products undergoing repairs. Offering service that surpassed existing norms—and customer expectations—in China helped Haier differentiate itself and build brand loyalty.

Haier also built a unified, dedicated logistics operation to distribute its products. Chinese competitors such as Midea and TCL had separate logistics operations for each product line. Haier’s scale and volume, coupled with consolidated distribution functions, gave the company one of the lowest logistics costs among competitors—a major advantage. Haier Logistics, an independently operated company created in 1999, was a national pioneer, offering just-in-time (JIT) purchasing, raw materials delivery, and product distribution. Five years after Haier established the logistics operation, the company had reduced the size of its main raw materials warehouse from a 200,000-square-meter facility with an inventory cycle of more than thirty days to a 20,000-square-meter distribution center with a seven-day inventory cycle, and the company reduced its roster of suppliers dramatically. Haier set up forty-two distribution centers across China, enabling the company to reach the country’s interior, and cut the time from order to final product delivery by more than one-third through the unified operation and information systems of Haier Logistics.

Haier Logistics provided a critical competitive advantage because of the institutional voids in China. Establishing a logistics network was complicated by geographic and bureaucratic obstacles across China’s varied terrain, unevenly developed roads and retail networks, and patchwork of local regulations. In large cities like Shanghai, it was difficult to find warehouse space large enough to accommodate the huge trucks required for white goods. In the most remote areas, it was a challenge to connect warehouses to a company’s information network. Regulations affecting transportation, such as weight limits for trucks, varied across regions.

Foreign multinationals were forced to rely on Chinese distributors and faced high costs and limited coverage in the absence of national third-party logistics providers. These constraints limited many foreign brands to China’s more developed eastern coast. Constructing a national network through multiple logistics providers was difficult and costly, and those that tried to run their own distribution networks often failed. Institutional voids made it difficult for Haier to build its business in China (see table 5-7), but, having circumvented them successfully, Haier found that voids served as barriers to the aspirations of its competitors.

Competitive advantage is dynamic—particularly competitive advantage built on local knowledge, which can be acquired by rivals over time, and institutional voids, which tend to be filled over time. Haier’s early focus on product quality and service standards helped the company survive consolidation and price wars, but these propositions become comparatively less valuable as the competitive field is culled and surviving rivals catch up. Moreover, the development of market institutions that assess product quality—the equivalent of Consumer Reports— over time makes it easier for new firms to establish credibility that Haier was able to achieve only over time through significant investments in brand building. The value of local customer knowledge can diminish over time as competitors gain experience—particularly foreign firms with initially steep learning curves—or are able to acquire local expertise through emulation, partnerships, and use of sophisticated market research intermediaries. As regulations ease the entry and development of capable third-party logistics providers with national scope and as the retail sector matures, the value of dedicated logistics and distribution operations, such as Haier’s, also can fall. (Chinese retailer Gome Electrical Appliances, for example, developed a nationwide footprint of 779 outlets across China as of mid-2009.)54

TABLE 5-7

Haier in China: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

Can companies easily obtain reliable data on customer tastes and purchase behaviors? Do world-class market research firms operate in the country? |

Underdeveloped market research intermediaries (product market information analyzers and advisers) |

Adapted: Exploited access to local knowledge with responsiveness to customer needs in product development, gaining advantage over competitors lacking access to local knowledge |

Can consumers easily obtain unbiased information on the quality of the goods and services they want to buy? Are there independent consumer organizations and publications that provide such information? |

Underdeveloped product information and certification providers (product market information analyzers and advisers; credibility enhancers) |

Adapted: Instilled focus on quality internally through worker accountability and focus of management |

How strong are the logistics and transportation infrastructures? Have global logistics companies set up local operations? Do large retail chains exist in the country? If so, do they cover the entire country or only the major cities? Do they reach all consumers or only wealthy ones? |

Underdeveloped third-party logistics and retail infrastructure (product market aggregators and distributors) |

Attempted to change market context: Established dedicated logistics arm and network of distribution centers across China |

How do companies deliver after-sales service to consumers? Is it possible to set up a nationwide service network? Are third-party service providers reliable? |

Underdeveloped after-sales service networks (product market aggregators and distributors) |

Attempted to change market context: Established service center with customer tracking, customer service hotline, and network of independent contractors making house calls to customers |

Emerging market-based companies can and should exploit their knowledge of local product markets and their ability to navigate the institutional context—even by filling institutional voids—but some of these advantages can become obsolete as home markets develop. (Indeed, Haier has seen its share of China’s domestic refrigerator market fall from 29.1 percent in 2004 to 25.6 percent in 2006 as a result of rising domestic and foreign competitors, some of which returned to the country after learning from early mistakes.)55

Wait, Stay, or Exit? Software Firms in India

In the face of institutional voids or other contextual challenges, emerging market-based companies can deemphasize their home markets by avoiding particular sectors or focusing on building global operations relatively early in their corporate histories.56 An entrepreneur might decide that a particular emerging market is not ready for a line of business if it will not be rewarded given the market’s institutional context. A biotech firm might decide that regulations or other obstacles would stifle its business in an emerging market. Entrepreneurs or business groups weighing investments in a wide range of sectors might decide that a market’s institutional context is not conducive to some investments—for example, the market simply might not be ready for private equity or big box retailing.

Software and IT consulting firms in India, such as Infosys Technologies, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), and Wipro Technologies, have exploited India’s labor force to offer IT services worldwide. These firms have developed globally competitive businesses based on their expertise and ability to identify, motivate, train, and manage talent. India boasts an abundance of software talent that is significantly cheaper than similar talent in developed markets. Given the institutional voids that pervade the Indian economy, however, it was difficult and costly for companies in developed markets to access this talent. Indian software companies developed business models and organizational capabilities that allowed them to match the talent in India with demand in developed markets.

Although these companies served domestic customers, early in their histories they focused on opportunities overseas, where these capabilities would be more highly rewarded. At the time that India’s software and IT consulting firms emerged, most Indian companies were not using sophisticated IT systems to support their businesses. Moreover, most of the few Indian companies with IT systems had in-house IT departments and were not willing to consider outsourcing. Developed markets offered deeper pools of customers—and higher price points for IT services than those same services sold to Indian companies.

Established in India in 1981, Infosys Technologies opened its first foreign office in the United States only six years later. Ten years after that, the company opened additional development centers in India and offices in Canada and the United Kingdom. By 1999, Infosys had opened offices in Germany, Sweden, Belgium, and Australia as well as development centers in the United States. The company opened additional development centers in Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States and, by 2001, offices in France, Hong Kong, the United Arab Emirates, and Argentina. In 2002–2003, Infosys established subsidiaries in China and Australia and offices in the Netherlands, Singapore, and Switzerland.

Given abundant access to cheap talent, an initial lack of reputation, and limited available hardware domestically, many Indian software providers started at the low end of the market with a “bodyshopping” model—sending talent into global markets to work on projects at client sites for significantly lower wages than local programmers. These companies gradually built reputations for reliability and high quality and began to provide more value-added services. Infosys, for example, reached a turning point in the mid-1990s when it began to initiate software development within India instead of exclusively at client sites. This was Infosys’s first step toward generating more value for its clients and protecting its claim on this value.

Although the transition was subtle, the results were monumental. The company was able to differentiate itself by growing from its baseline labor-commodity model—selling qualified labor inputs at a low price to build value into other companies’ businesses. Infosys successfully moved up the value chain by providing specialized services and solutions that were designed and managed by highly qualified technical engineers and programmers. Instead of simply offering cheap and talented—but increasingly replicable—labor input, the company offered valuable IT services to clients, moving further up the value chain to providing complete turnkey solutions for Fortune 500 companies, most of them based outside India (see table 5-8).

TABLE 5-8

Software firms in India: Responding to institutional voids

| Spotting voids question | Specific void | Response |

|---|---|---|

How strong is the country’s education infrastructure, especially for technical and management training? Is data available to help sort out the quality of the country’s educational institutions? |

Underdeveloped educational system beyond global tier (labor market aggregators and distributors); under-developed certification intermediaries (labor market credibility enhancers) |

Adapted: Exploited local knowledge and developed ability to identify talent |

Are consumers willing to try new products and services? Do they trust goods from local companies? How about foreign companies? |

Limited business-to-business market for services because sophisticated IT systems not pervasive in India and outsourcing of IT not widely adopted practice |

Exited: Sought out customers in developed markets early in corporate histories |

Business Groups

While executing any of the strategies discussed here, many prospective emerging giants have adopted business group organizations to reduce the costs of institutional voids in their home markets.57 The Ayala Group in the Philippines, the Koç Group in Turkey, the Tata Group in India, Luksic Group in Chile, and Grupo Carso in Mexico are among the many successful emerging market-based business groups that have developed internal capabilities to deal with institutional voids in their respective countries. Think of business groups as agglomerations of firms that typically are legally independent, often diversified across a range of industries, and tied together to varying extents by formal links (equity ties, common board members, common brand names) and informal links, such as control by various members of a family.

As a form of organization, business groups are considered by many observers in developed Western markets to be anachronistic. This form of organization, however, makes sense in emerging markets in light of institutional voids. When entering a new line of business, group organizations often can bypass the voids faced by another start-up by using the capital, talent, or reputation built by another business in the group. The business group can thus serve as a private equity firm, executive search firm, and branding consultant in a market that lacks a sophisticated network of these intermediaries.

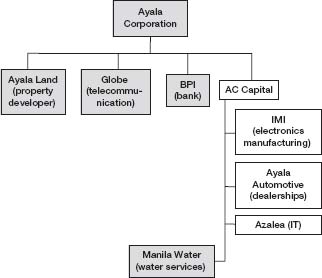

Ayala Corporation of the Philippines, for example, grew from a family real estate company into a highly diversified business group with holdings in telecommunications, financial services, IT, and other sectors (see figure 5-1 for the structure of major Ayala companies). Some of these firms were publicly traded (shaded gray in the figure).

FIGURE 5-1

Ayala Corporation business group structure

Source: Ayala Corporation Annual Report 2007.

To oversee the unlisted group companies, Ayala established AC Capital in 2002. AC Capital functioned somewhat like an internal venture capital or active investment management firm, filling an institutional void in risk capital provision. “AC Capital has a distinct mandate, which is to have a more active management of the emergent businesses,” said Ayala treasurer Ramón Opulencia. “AC Capital plays the role of an investment company for them, deciding whether to nurture them or to harvest value for the corporation.”58 Manila Water Company, one of the companies nurtured under AC Capital, went public in 2005.59 Ayala’s group resources and time horizon enabled it to launch Globe Telecom in the face of steep challenges—high costs, sometimes contentious government relations, entrenched incumbents—that would have been much more difficult for a new entrepreneur to manage.60

A group structure can enable emerging market firms to develop a corporate brand name that signifies quality, trust, and transparency. Business groups can help defray the cost of building and maintaining a brand by spreading it across multiple arms of their businesses. The business media in emerging market countries abound with advertisements that promote group identity rather than merely emphasize the products or services of individual companies within a group. Once established, these brands wield tremendous power. Consumers in these countries value group brands; these groups have an incentive not to damage brand quality in any one business, because they will pay the price in other businesses as well.

A business group with a reputation for quality products and services can use its group name to enter new businesses, even if those businesses are unrelated to its current product lines. The Korean chaebols are perhaps most well known for extending their group identity over multiple product categories. The Samsung brand, for instance, emerged quickly worldwide as Samsung affiliates produced goods as wide ranging as televisions, commercial ships, chemicals, mobile phones, and microwave ovens.61 Many groups in Brazil, China, India, Malaysia, and Turkey have successfully employed similar strategies of diversification.

Business groups can also exploit their reputations to raise capital in local stock markets. Diversified groups can point to their track record of returns to raise money from investors for new ventures. Business groups also can use their own internally generated capital to grow existing businesses, including those too small to obtain capital from financial institutions, or to enter new industries—in effect acting as venture capitalists.

Additionally, because of their ability to circumvent local institutional voids, established local business groups often become partners of choice for multinationals when they enter emerging markets. Group structures can also make emerging market companies more attractive to foreign investors eager to tap in to these fast-growth markets. With few reliable financial analysts and knowledgeable mutual fund managers to guide them, outsiders instead turn to diversified groups, which, in turn, invest in a wide range of industries. Investors trust groups to evaluate new opportunities and to exercise an auditing and supervisory function—in effect serving as quasi-mutual funds.

The groups thus become the conduit for large amounts of investment in their capital-starved countries. When Jardine Matheson—a business group based in Hong Kong—sought to invest in India, it purchased a 20 percent stake in Tata Industries (the Tata Group’s new business development arm) in 1996, giving it exposure to a wide swath of industries in the country.

Group structures can also help emerging market firms access, attract, and develop management talent in the still-developing labor markets of their home countries. Management training intermediaries, such as business schools, are not well established in emerging markets, and conglomerate organizations can spread the fixed costs of professional development over the businesses in the group.

Many of the large groups in India, for example, have internal management development programs, often with dedicated facilities. These programs typically are geared toward developing the skills of experienced managers. Some groups, however, have instituted training programs for all levels of employees in an attempt to develop a broad range of human capital. Some of the Korean chaebols have set up special training programs in collaboration with top U.S. business schools.

The mobility of talent across industries in emerging markets is hindered by the absence of executive search firms in these countries. By offering opportunities and exposure to management challenges in a variety of industries, business group affiliates can attract managerial talent that they would not be able to do as stand-alone entities.

Finally, governments in emerging markets usually make it difficult for companies to adjust their workforces to changing economic conditions. Rigid laws often prevent companies from laying off employees, and labor unions insist on job security in the absence of government provided unemployment benefits. The internal labor markets of business groups can help counteract these rigidities and offer job security in economies that have few safety nets. When one company in a group faces declining prospects, its employees can be transferred to other group companies that are on the rise—even to companies in otherwise undesirable locations.

Some Indian business groups, for example, have built communities around their production facilities in remote parts of the country. Because the group provides services such as schools, hospitals, and places of worship, and because there will eventually be career options in more attractive locations when the group is present, managers and other trained employees are more willing to relocate. The growing companies benefit by receiving a ready source of reliable employees.62

Groups are also able to put new talent to good use. By allocating talent to where it is most needed, conglomerates gain a head start in beginning new activities. Wipro Technologies in India, for example, successfully moved beyond computers into financial services by relocating skilled engineers first to computer-leasing services that would make use of their technical know-how and then to a broad range of financial services. In contrast, to build their operations, unaffiliated companies usually need to recruit publicly—a difficult proposition in countries where labor varies widely in quality and lacks certification from respected institutions.

There are risks, however, for emerging market-based companies that organize themselves as business groups. Even though internal financing within business groups offers the obvious advantage of its low cost relative to funding available through external arms-length sources in markets that lack specialized financial intermediaries, this funding method comes at a potential price. Without the external monitoring provided by arms-length investors, internal cash flows are more easily diverted to ill-advised investments.