Two

Spotting and Responding to Institutional Voids

THIS CHAPTER BUILDS ON OUR structural definition of emerging markets to equip managers with toolkits to spot and respond to institutional voids.1 Emerging markets are hardly uniform in the nature and extent of their institutional voids. The development of business strategy in any economy is driven by three primary markets—product, labor, and capital—and institutional voids can be found in any, or all, of these markets in developing countries.

The advantage of an institutional approach to considering emerging markets is that it specifies the particular combination of features that prevents efficient exchange in each market. Some countries might lack specialized intermediaries in the labor market but have them in abundance in the capital markets. Others may have effective labor markets but distorted capital markets. Product and factor markets within developing countries often develop at different rates.

Chile is lauded for its capital market efficiency, whereas Korea’s financial markets remain constrained by the entanglement between banks and its chaebol business groups (see figure 2-1). At the same time, Korea has undergone spectacular development in its product markets, as evidenced by its world-leading broadband penetration, while Chile’s communications infrastructure is not nearly as developed (see figure 2-2). Moreover, different industries are not uniform in the ways in which they rely on market institutions. Some industries are more institution intensive than others, so different industries within the same market are affected differently by institutional voids.

FIGURE 2-1

Comparing financial markets in Korea and Chile

Source: The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators, WDI Online.

This structural definition has actionable implications for managers. Institutional voids have real and first-order effects on business strategy.2 Companies rely on intermediaries both to raise the willingness to pay (WTP) of consumers and to lower companies’ own costs. Companies need the expertise of market research firms, for example, to understand customer preferences and then adapt their offerings to raise WTP. Identifying and segmenting the market are immeasurably more difficult without market research specialists acting as intermediary.

In terms of company operations, a firm’s options for supply chain management, for example, depend entirely on available logistics intermediaries. Operating in a market that lacks logistics providers has predictable and measurable effects on inventory carrying costs. Moreover, financing options depend on capital market intermediaries, such as commercial and investment banks. Raising external capital requires credibly convincing external capital providers that the money being sought will be used in the way that is intended. This would be highly difficult if there were no independent auditors and if there were no recourse mechanisms available to investors in the face of after-the-fact disputes. Human resource capabilities depend on intermediaries such as business schools and executive search firms. Identifying and screening candidates for managerial positions entirely in-house carry significant costs.

FIGURE 2-2

Comparing product markets in Korea and Chile

Source: The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators, WDI Online.

Therefore, for anyone interested in managing or investing in emerging markets, spotting institutional voids is a key first step. To facilitate this task, we have developed a series of questions shown in this chapter’s toolkits.3 Systematically answering these questions can give an organization important insights into the way a particular emerging market is likely to work or not work.

Consider how a few examples of these questions illustrate the variance in market infrastructure between developed and emerging markets, as well as among different emerging markets (see toolkit 2-1).

Toolkit 2-1

Applying the Spotting Institutional Voids Toolkit (Markets)

Product Markets

1. Do large retail chains exist in the country? If so, do they cover the entire country or only the major cities? Do they reach all consumers or only wealthy ones?

Business Implications: Can we reach the customers we hope to reach in an efficient manner? As an entrepreneur with little market reputation, can we piggyback on the credibility of the chain stores to convince customers to trust the quality of our products?

Sources: Euromonitor International, Country Market Insight, “Retailing–US” (May 2007), “Brazilian Retailing” (February 2007), “Russian Retailing” (October 2006), “Indian Retailing: Market Overview” (June 2007), “Chinese Retailing: Market Overview” (March 2007); Nandini Lakshman, “Protesters Tell Wal-Mart to Quit India: Foreign Retail Giants Such as Wal-Mart and Germany’s Metro, Along with Local Chain Reliance Retail, Face Pressure from Small-Trade Workers,” BusinessWeek Online, October 15, 2007.

2. Do consumers use credit cards, or does cash dominate transactions? Can consumers get credit to make purchases? Is data on customer credit worthiness available?

Business Implications: How can we evaluate the creditworthiness of our customers?

Sources: Financial card data and analysis from Euromonitor International, Country Market Insight, “Financial Cards–US” (March 2007), “Financial Cards–Brazil” (February 2007), “Financial Cards–Russia” (March 2006), “Financial Cards–India” (March 2007), “Financial Cards–China” (May 2007), and data derived from population figures from The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators, WDI Online. Credit coverage data from The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators, WDI Online.

3. Is there a deep network of suppliers? How strong are the logistics and transportation infrastructures?

Business Implications: Can we manage inventory using modern vendor management techniques and collaborate with supply chain partners efficiently to minimize cost and maximize flexibility?

Labor Markets

1. How are the rights of workers protected? How strong are the country’s trade unions? Do they defend workers’ interests or only advance a political agenda?

Business Implications: What constraints do we face in the hiring, firing, and management of our employees?

2. Does a deep pool of local management talent exist? Does the local culture accept foreign managers? Can employees move easily from one company to another? Does the local culture support that movement? Do recruitment agencies facilitate executive mobility?

Business Implications: Can we staff our operations adequately? Can we count on lateral hiring, or do we need to rely exclusively on entry-level hiring and internal talent development?

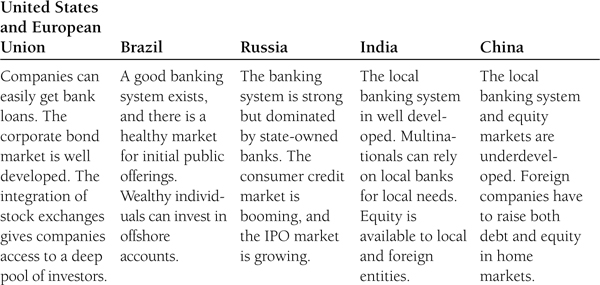

Capital Markets

1. How effective are the country’s banks in collecting savings and channeling them into investments? Can companies raise large amounts of equity capital in the stock market? Is there a market for corporate debt?

Business Implications: Can we raise adequate funding with appropriate capital structures at a reasonable cost?

2. How reliable are sources of information on company performance? Do the accounting standards and disclosure regulations permit investors and creditors to monitor company management?

Business Implications: How can we evaluate potential partners and investment opportunities?

Adapted and reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. From “Strategies That Fit Emerging Markets,” by Tarun Khanna, Krishna G. Palepu, and Jayant Sinha, June 2005. Copyright © 2005 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

The Macro Context

Institutional voids in factor and output markets are shaped by the broader macro context of emerging economies. Politics, history, and culture affect Spotting and Responding to Institutional Voids | 35 the development, form, and function of institutions and the existence and persistence of institutional voids. In capital markets, for example, the development of financial reporting and independent auditing depends on transparency and trustworthiness. It also depends on the willingness of the state to open its capital markets to analysis and public scrutiny.

The ability to create value in product markets may also be hampered by a closed economic context wherein consumers are uncomfortable or unwilling to share information about their tastes and needs. It may prove troublesome to build market research institutions in this environment. Additionally, the rule of law and the regulatory institutions that govern efficient transacting in developed markets may be conspicuously absent in economies that have significant asymmetries of power resulting from a transitional country’s sociopolitical heritage.

It may appear that we are singling out closed economies, but open economies can also impair institutional change. The democratic process, as in India, sometimes hinders the development of a predictable regulatory climate or the rapid development of infrastructure. The political back-and-forth inherent in a democracy slows the rate of change and concurrently makes it hard to ignore the prevailing vested interests that might be affected by the birth of new market institutions. For example, the entry of mass retailers has been subject to severe restrictions in India because of the aggressive lobbying and political clout of the small retailers. In this respect, aggressive state mandates can sometimes be more effective than the democratic process in implementing institutional change.

In light of the importance of the political and social systems in emerging markets and their openness to investment and the flow of information, we have included questions in the “Spotting institutional voids” toolkit relating to macro context (see toolkit 2-2).

Developing the capability to spot institutional voids can help companies from developed markets in two ways. It not only can help them pursue business opportunities in emerging markets but also may open their eyes to opportunities and challenges in their own markets. If top executives, boards, analysts, and regulators of financial firms in the United States had appreciated the institutional voids in the mortgage industry, for example, many of the problems exposed in the financial crisis might have been avoided. As policy makers in the United States and elsewhere consider reforms to prevent future financial crises, they need to keep institutional voids in mind.

Toolkit 2-2

Applying the Spotting Institutional Voids Toolkit (Macro Context)

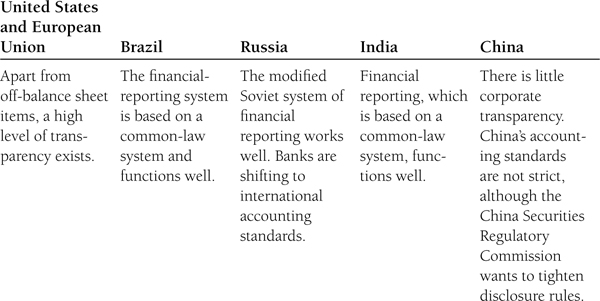

1. How vibrant and independent are the media? Are nongovernmental organizations, civil rights groups, and environmental groups active in the country?

Business Implications: What other stakeholders does my business need to consider?

2. What restrictions does the government place on foreign investment? Can a company make greenfield investments and acquire local companies, or can it break into the market only by entering into joint ventures?

Business Implications: Is competing alone an option for my business, or do we need to seek out a partner?

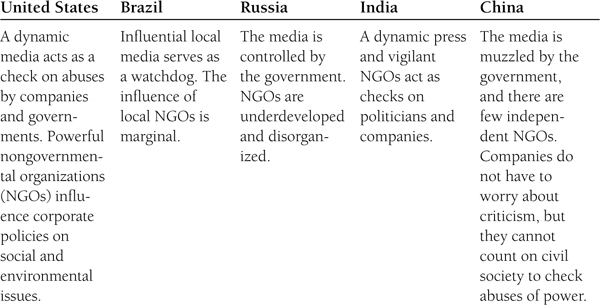

3. How long does it take to start a new venture in the country?

Business Implications: What bureaucratic impediments to establishing operations can my business expect? What does this signal for government’s attitude toward future growth and development of my business in this country?

![]()

Source: The World Bank Group, World Development Indicators 2007, WDI Online.

Adapted and reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. From “Strategies That Fit Emerging Markets,” by Tarun Khanna, Krishna G. Palepu, and Jayant Sinha, June 2005. Copyright © 2005 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

Market Segments in Emerging Markets

Before responding to institutional voids, companies need to audit the local context to identify voids. Companies also need to appreciate the importance of market segments in emerging markets. Different strategies in response to institutional voids position multinationals and domestic firms to reach different segments. Market segments in emerging markets are distinguished not only by income and prices but also by needs, tastes, and psychographic characteristics. Targeting particular segments requires particular capabilities and knowledge, and not simply different price points.

The product markets in emerging economies can be divided into global, emerging middle class, local, and bottom segments, which are distinguished by combinations of three variables: price, quality, and features (see table 2-1).

The global segment consists of consumers who want offerings having the same attributes and quality as products in developed countries and who are willing to pay global prices for them. The emerging middle class segment consists of consumers who demand products or services having a combination of global and local price, quality, and features. A customer might be willing to pay global prices and expects global quality, but desires local features. For example, Chinese and Indian executives may prefer to stay in a Shangri-La or Taj hotel rather than at a Four Seasons.

Some customers in emerging markets might look for products with global (or near-global) quality but with local features and prices. An example of this local segment would be a family in a developing market looking for a washing machine with world-class reliability but tailored to their local living conditions—such as space constraints, power consumption, and water consumption—and local prices. Some combinations of local and global price, quality, and features can be ruled out as not logically viable (such as products with local quality and features but global prices). Lower-middle-class consumers in the local segment are happy with products of local quality and features and at local prices.

TABLE 2-1

Market segments in emerging economies

Note: Some theoretical combinations can be ruled out by logic.

a. Some foreign players have targeted this segment with products that require foreign-developed technology—though pared-down features—through subsidized initiatives such as One Laptop Per Child.

The bottom of the market consists of people who can afford only the least-expensive products. C. K. Prahalad of the University of Michigan has called this market segment the “bottom of the pyramid.”4

Understanding these segments can help multinationals as well as domestic companies in emerging markets tailor their business models and growth strategies. Before the opening of emerging markets, local companies dominate all segments. Market leaders typically straddle all segments, because these firms are the only game in town.

But when markets open up, multinationals based in developed markets quickly displace local companies in the global segment, because that is their natural niche of global quality at global price. Because of the institutional voids in developing countries, some multinational companies find it difficult to serve anything except this segment. The lack of market research makes it tough for multinational companies to understand customers’ tastes, and limited distribution networks often prevent them from delivering products to customers outside large urban centers and thereby reach the local segment.

Local companies, because of their legacy, can dominate the local segment. Local knowledge is a powerful source of competitive advantage in the local segment, both to tailor products and to navigate voids. This large segment is not going away. Even as some customers in this segment move into the emerging middle class, economic growth refills the local segment as poorer consumers move into it.

Neither developed market-based multinationals nor aspiring emerging giants are satisfied with the status quo. The quest for growth leads both types of organizations to vie for the attention of the emerging middle class segment. Neither type, however, can lay claim to this segment with its existing offerings. Multinationals need to localize their products to reach local price points. These companies need local knowledge as they redesign products to successfully pare down features, retaining only those that are truly valued by local customers—without sacrificing quality. Local companies need to deliver higher-quality items and to design products that satisfy unique local needs. (Some local companies can even grab a part of the global segment, provided they can reach global quality levels and offer products and services that truly cater to the local sensibilities and even national or cultural pride of local elites.) Both multinationals and local companies need to stretch to compete in the emerging middle class segment.

Companies operating in emerging markets also need to think about segmentation as it relates to factor markets. In talent markets, multinationals often do not have enough knowledge about the local talent pool to design policies that will attract and motivate employees outside the global segment of employees trained by global institutions and compensated with global salaries. Local companies, by contrast, can take advantage of their local knowledge and familiarity with voids in labor markets to identify and sort talent outside this global segment.

Responding to Institutional Voids

Companies cannot operate in emerging markets without encountering institutional voids, but once they identify the voids that will shape the environment for their businesses, they can find ways to overcome them.5 Recognizing the costs of institutional voids, companies might decide to build a business to fill institutional voids. In chapter 3 we look at the opportunities and challenges facing companies seeking to exploit voids as entrepreneurial opportunities. Multinationals and emerging market-based companies that do not build full businesses to fill institutional voids face a set of strategic choices and menu of options to respond to them (see table 2-2).

Replicate or Adapt?

Developed market-based multinationals have built their businesses on the foundation of well-developed institutional contexts. Executing these models in emerging markets, which lack such a foundation, is a challenge. Multinationals enter emerging markets without local knowledge or reputation, but often they can exploit their global capabilities by tapping in to global factor markets for capital, talent, or know-how or by leveraging the credibility that comes with being a global brand.

TABLE 2-2

Responding to institutional voids

Simply exploiting these advantages—replicating the model of their home market—can enable multinationals to enter emerging markets without significant disruption and without facing significant institutional voids, but often these strategies position multinationals only to tackle the global market segment. To compete in the emerging middle class and local segments, multinationals need to adapt their products, services, business processes, or organizations. Adaptation is difficult because of institutional voids. When tailoring and marketing a product for a developed market overseas, a multinational can hire an advertising agency or other branding consultant in that country. Emerging markets often lack these intermediaries. Other forms of adaptation can help multinationals circumvent institutional voids.

Replicating business models developed outside their borders—particularly in developed markets—is not a viable option for emerging market-based companies that seek to build competitive advantage. Prospective emerging giants can exploit their local knowledge of product markets or factor markets, their established reputation, or other local resources to gain advantage in the market. By exploiting local knowledge and capabilities, emerging market companies can adapt their offerings, processes, and organizations to institutional voids.

Compete or Collaborate?

Institutional voids often stifle the entry of multinationals into emerging markets because they lack local knowledge or capabilities to get around these voids. Multinationals can counter this disadvantage by launching joint ventures (JVs) or other partnerships with local companies or by quickly localizing their staffs. Many local companies in these markets have internalized some roles served by market intermediaries in developed markets and, as a result, can be resourceful partners for multinationals entering emerging markets. Local companies, meanwhile, can exploit partnerships or other forms of collaboration with multinationals to help develop global capabilities or other resources—as well as credibility.

Accept or Attempt to Change Market Context?

Companies operating in emerging markets can take institutional voids as a given, or they can more actively engage with the institutional context by filling voids in service of their businesses. This strategy can be implemented in a number of ways. Consider the challenges facing a retailer operating in India. Hoping to sell fresh produce in a country that lacks a well-developed cold chain distribution system, the retailer could either build a cold chain itself or could induce another party to build it through cooperation, shared investment, or contracting for a guaranteed minimum amount of business.

If the company chooses to fill the void itself, it could do so simply as a catalyst and later exit its intermediary role, or it could build these operations into a business to serve other companies as well (exploiting the void as an entrepreneurial opportunity). Practical difficulties or regulations might prevent a foreign third-party logistics provider from building comprehensive infrastructure in an emerging market on its own. The company could still fill the void by providing port-to-port logistics and partnering with a local company to connect its operations deeper into the market or by inducing government or another entity to invest in infrastructure development through contracted business guarantees.

Enter, Wait, or Exit?

Some institutional voids are beyond the capabilities of either local or multinational firms to circumvent or otherwise alter. When faced with such situations, companies can emphasize business opportunities in other markets that do not present such voids. This exit option can come in various forms. An emerging market company might maintain a presence in its home market while investing more seriously in markets that are more conducive to growth or learning beyond its borders. Similarly, a multinational might delay significant investment in a particular emerging market until regulations pertaining to foreign firms are changed.

In chapters 4 and 5, we look at how companies operating in emerging markets have faced these strategic choices. In chapter 6, we turn to the globalization journeys of emerging giants. The strategic choices to respond to institutional voids do not apply as clearly to emerging market-based companies as they go global, but the institutional contexts of their home markets do shape their journeys. Emerging giants can replicate their home market-developed capabilities by entering other emerging markets having similar market segments and institutional contexts. To enter developed markets, these companies—like multinationals entering emerging markets—need to adapt their products, capabilities, or organizations to new market contexts, although with better-developed market infrastructure and more-demanding customers than in their home markets.

Emerging giants can go global not only by entering new markets but also by building global capabilities. These companies are increasingly able to “borrow” market institutions from developed markets to augment their capabilities. For example, a company from a country lacking well-developed financial markets could list itself on a foreign stock exchange through a global depository receipt (GDR) or American depository receipt (ADR). Not only can this approach help the company raise capital, but also it serves as a signal that the company meets international standards of corporate governance and sees itself as globally oriented. Foreign acquisitions are another avenue for emerging market companies to use in accessing global brands, talent, or know-how. These companies can also take advantage of connections to networks of their country’s diaspora living overseas to tap in to foreign resources.

Persistent Voids, Anchored Strategies

The responses to institutional voids described in this chapter are not mutually exclusive or irrevocable choices. They can be successfully employed simultaneously or in different sequences. As institutional contexts in emerging markets evolve, corporate strategies will often need to change accordingly. Strategic positioning based on institutional voids is likely to be sustainable to some extent, however, because of the likely persistence of institutional voids. Much as markets cannot be mandated into existence, institutional voids cannot be mandated out of existence. Generally, government and private enterprise can fill voids only with the passage of time and experimentation, and not by fiat. As a result, challenges from market gaps—and opportunities to bridge them—persist. The presence or absence of intermediaries matters for strategy and the sustainability of competitive positioning.

There is no simple, straightforward formula for navigating the unique challenges of emerging markets, but companies operating in these markets will inevitably encounter institutional voids and they need not be paralyzed by them. Looking at institutional voids through common-sense approaches—assessing strengths and adapting accordingly, building capabilities, reshaping the environment, or biding time until the context changes—gives companies a palette of ways to assess and seize opportunities in these markets. Developing a more granular appreciation of an emerging market’s institutional context up front can help managers avoid easy-to-anticipate mistakes and even identify unexpected sources of competitive advantage.

Toolkit 2-3

Spotting Institutional Voids in an Emerging Market

Product Markets

- Can companies easily obtain reliable data on customer tastes and purchase behaviors? Are there cultural barriers to market research? Do world-class market research firms operate in the country?

- Can consumers easily obtain unbiased information on the quality of the goods and services they want to buy? Are there independent consumer organizations and publications that provide such information?

- Can companies access raw materials and components of good quality? Is there a deep network of suppliers? Are there firms that assess suppliers’ quality and reliability? Can companies enforce contracts with suppliers?

- How strong are the logistics and transportation infrastructures? Have global logistics companies set up local operations?

- Do large retail chains exist in the country? If so, do they cover the entire country or only the major cities? Do they reach all consumers or only wealthy ones?

- Are there other types of distribution channels, such as direct-to-consumer channels and discount retail channels, that deliver products to customers?

- Is it difficult for multinationals to collect receivables from local retailers?

- Do consumers use credit cards, or does cash dominate transactions? Can consumers get credit to make purchases? Is data on customer creditworthiness available?

- What recourse do consumers have against false claims by companies or defective products and services?

- How do companies deliver after-sales service to consumers? Is it possible to set up a nationwide service network? Are third-party service providers reliable?

- Are consumers willing to try new products and services? Do they trust goods from local companies? How about foreign companies?

- What kind of product-related environment and safety regulations are in place? How do the authorities enforce regulations?

Labor Markets

- How strong is the country’s education infrastructure, especially for technical and management training? Does it have a good elementary and secondary education system as well?

- Do people study and do business in English or in another international language, or do they mainly speak a local language?

- Is data available to help sort out the quality of the country’s educational institutions?

- Can employees move easily from one company to another? Does the local culture support that movement? Do recruitment agencies facilitate executive mobility?

- What are the major post-recruitment training needs of the people whom multinationals hire locally?

- Is pay for performance a standard practice? How much weight do executives give seniority, as opposed to merit, in making promotion decisions?

- Would a company be able to enforce employment contracts with senior executives? Could it protect itself against executives who leave the firm and then compete against it? Could it stop employees from stealing trade secrets and intellectual property?

- Does the local culture accept foreign managers? Do the laws allow a firm to transfer locally hired people to another country? Do managers want to stay or leave the nation?

- How are the rights of workers protected? How strong are the country’s trade unions? Do they defend workers’ interests or only advance a political agenda?

- Can companies use stock options and stock-based compensation schemes to motivate employees?

- Do the laws and regulations limit a firm’s ability to restructure, downsize, or shut down?

- If a company were to adopt its local rivals’ or suppliers’ business practices, such as the use of child labor, would that tarnish its image overseas?

Capital Markets

- How effective are the country’s banks, insurance companies, and mutual funds in collecting savings and channeling them into investments?

- Are financial institutions managed well? Is their decision making transparent? Do noneconomic considerations, such as family ties, influence their investment decisions?

- Can companies raise large amounts of equity capital in the stock market? Is there a market for corporate debt?

- Does a venture capital industry exist? If so, does it allow individuals with good ideas to raise funds?

- How reliable are sources of information on company performance? Do the accounting standards and disclosure regulations permit investors and creditors to monitor company management?

- Do independent financial analysts, rating agencies, and the media offer unbiased information on companies?

- How effective are corporate governance norms and standards in protecting shareholder interests?

- Are corporate boards independent and empowered, and do they have independent directors?

- Are regulators effective in monitoring the banking industry and stock markets?

- How well do the courts deal with fraud?

- Do the laws permit companies to engage in hostile takeovers? Can shareholders organize themselves to remove entrenched managers through proxy fights?

- Is there an orderly bankruptcy process that balances the interests of owners, creditors, and other stakeholders?

Macro Context

- To whom are the country’s politicians accountable? Are there strong political groups that oppose the ruling party? Do elections take place regularly?

- Are the roles of the legislative, executive, and judiciary clearly defined? What is the distribution of power between the central, state, and city governments?

- Does the government go beyond regulating business to interfering with it or running companies?

- Do the laws articulate and protect private property rights?

- What is the quality of the country’s bureaucrats? What are bureaucrats’ incentives and career trajectories?

- Is the judiciary independent? Do the courts adjudicate disputes and enforce contracts in a timely and impartial manner? How effective are the quasi-judicial regulatory institutions that set and enforce rules for business activities?

- Do religious, linguistic, regional, and ethnic groups coexist peacefully, or are there tensions between them?

- How vibrant and independent is the media? Are newspapers and magazines neutral, or do they represent sectarian interests?

- Are nongovernmental organizations, civil rights groups, and environmental groups active in the country?

- Do people tolerate corruption in business and government?

- What role do family ties play in business?

- Can strangers be trusted to honor a contract in the country?

- Are the country’s government, media, and people receptive to foreign investment? Do citizens trust companies and individuals from some parts of the world more than others?

- What restrictions does the government place on foreign investment? Are those restrictions in place to facilitate the growth of domestic companies, to protect state monopolies, or because people are suspicious of multinationals?

- Can a company make greenfield investments and acquire local companies, or can it break into the market only by entering into joint ventures? Will that company be free to choose partners based purely on economic considerations?

- Does the country allow the presence of foreign intermediaries such as market research and advertising firms, retailers, media companies, banks, insurance companies, venture capital firms, auditing firms, management consulting firms, and educational institutions?

- How long does it take to start a new venture in the country? How cumbersome are the government’s procedures for permitting the launch of a wholly foreign-owned business?

- Are there restrictions on portfolio investments by overseas companies or on dividend repatriation by multinationals?

- Does the market drive exchange rates, or does the government control them? If it’s the latter, does the government try to maintain a stable exchange rate, or does it try to favor domestic products over imports by propping up the local currency?

- What would be the impact of tariffs on a company’s capital goods and raw materials imports? How would import duties affect that company’s ability to manufacture its products locally versus exporting them from home?

- Can a company set up its business anywhere in the country? If the government restricts the company’s location choices, are its motives political, or is it inspired by a logical regional development strategy?

- Has the country signed free-trade agreements with other nations? If so, do those agreements favor investments by companies from some parts of the world over others?

- Does the government allow foreign executives to enter and leave the country freely? How difficult is it to get work permits for managers and engineers?

- Does the country allow its citizens to travel abroad freely? Can ideas flow into the country unrestricted? Are people permitted to debate and accept those ideas?

Adapted and reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. From “Strategies That Fit Emerging Markets,” by Tarun Khanna, Krishna G. Palepu, and Jayant Sinha, June 2005. Copyright © 2005 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.