CHAPTER 9

Bad Connections How to Turn Angry Customers into Partners

Service is a performance, much like a stage play. Put yourself in the audience of the one-act service play to follow.

Act 1, Scene 1:

The Service Desk at Acme Encore:

Used Computers, New Software & Fast Repairs

“I bought a new accounting software package and I can’t get it to load,” the well-dressed, gray-haired gentleman confided to the twentysomething service tech behind the service counter. John was behind him in line waiting to pick up a repaired laptop computer left the previous week.

“You probably loaded it wrong,” the service tech snapped, without looking up from the paperwork he was completing. The customer moved forward, raised himself several inches taller, and peered down with obvious disdain at the young tech.

“What do you mean I loaded it wrong! Young man, I’ve been loading computer programs since the Macintosh in ’85. I think it’s the computer your company sold me two months ago.” His decibel level was noticeably higher.

“Well if you bought it two months ago, the 30-day warranty is up and we can’t help you anyway. You’ll just have to send it to the manufacturer for repair.” The service tech seemed pleased to pass the customer and his problem on down the line.

“No! That’s not good enough,” said the now clearly angry customer. “You sold me a defective product and now you are making me do all the work. I want to talk to your boss.”

“You can talk all you want to, mister, but it won’t change our policies. Now, please let me deal with the next customer.” Being the next customer in line, John was really thrilled by the prospect of being this smug little critter’s next victim!

Act 1, Scene 2:

Acme Encore—The Boss’s Office

“Mr. Careless will see you now,” the receptionist said as she escorted the angry customer into the boss’s office.

“How can I help you, sir?” said Mr. Careless as he greeted the upset customer.

“You can start by firing that sorry *@# tech on your service desk. He was rude, disrespectful, and completely uninterested in helping me, or, for that matter, caring about your reputation!”

You could almost hear the boss thinking, “We have a very bad connection!”

Curtain closes.

Ever wonder why electricians refer to an ineffective electrical connection as a “bad” connection, like it was misbehaving and in need of punishment? It is how many service providers view angry customers—not as someone who has experienced a failed service connection, but as the perpetrator of a “bad” connection. As long as the customer with a beef is viewed as “bad” rather than “injured,” the more efforts to right the customer connection will simply short-circuit.

Bad connections happen! Fortunately, today’s customers, as restless, short-tempered, and impatient as they may be, do not expect service providers to be perfect. They know service is powered through human relationships and “To err is human.” They do expect organizations always to demonstrate they care in the face of any customer disappointment. In the words of renowned author and Texas A&M professor Len Berry, “The acid test of service quality is how you solve customers’ problems.”1

Fixing Problems vs. Healing Relationships

The field of service recovery has had a rather sordid history. Recall some of the super-botched recovery examples—Ford Explorer, the Exxon Valdez, the BP Gulf oil spill—and you discover that someone at the helm likely determined that service recovery was all about damage control, not about customer healing. Without fixing the disappointed customer, all manner of physical repair of the customer’s issue will be for naught.

Everyone who has frequented a fast food restaurant has had the experience of the drive-in or counter clerk occasionally getting the order wrong. Say, you ordered a large fries but you received a small fries instead. As customers, we know there will be an occasional error, especially in a setting where speed is a factor. We don’t go to a quick service establishment for slow service. The memorable part is how they handle the hiccup. If the server makes no eye contact, registers no remorse, and shows zero empathy, even if the incorrect order is corrected, as customers, we end up angrier than we were with the initial mistake.

Fixing the customer’s problem is crucial. That is what customers assume will happen. It is emotional healing that trumps problem repair. As the oft-quoted line goes: “Customers don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” It is the relationship side, not the engineering side, of service recovery that keeps service providers off the “don’t go there” list.

If customer healing is emotional, it is beneficial to examine what is happening in the customers’ minds behind their feelings of disdain, disappointment, or anger. Let’s take a tour inside that mind, looking at what’s going on from the customer end of a bad connection.

All service experiences begin with an expectation of fairness. When things go sour, for whatever reason, customers also have preconceived ideas about what should happen to set things right. Customers of a utility have different standards for recovery during a storm than when the same outage occurs because the power company goofed.

When their recovery experience approximates their recovery expectation, the customer is in emotional balance. As we earlier noted, most—though certainly not all—customers assume the world will treat them fairly. This is not a mark of naiveté, simply recognition that, on balance, most customers have more life experiences that fall on the “fair” than on the “not fair” side of the ledger.

So when a service provider acts in a manner the customer deems unfair, customers feel betrayed—an implied promise was not honored and the service covenant has thus been violated. What is critical to great recovery is an understanding that customers’ views of the world are always accurate and reasonable from their point of view, not necessarily from the viewpoint of the service provider. As the country adage goes, “It is easier to turn a mule if you first get the mule moving.” Starting where the customer is, getting in their shoes, is tantamount to guiding them to a happy ending. In the customer’s eyes, you are not qualified to change their view until you first demonstrate you completely understand their view.

Customers do make mistakes, and they know they make mistakes. But whether they caused the error themselves, it was an act of nature, or the organization was the cause, they assume their view of what should happen after a service hiccup is the only right, or reasonable, course of action. When that view is directly challenged or questioned in any way, customers don’t just assume their challenger is wrong; they see it as an attempt to control, prevail, coerce, or engage in all manner of unrighteous action.

The Psycho-Logic of Customer Healing

Understanding the customer’s emotional state when events veer far off their anticipated course, when an expected right turn suddenly becomes a left, is an essential first step in balancing the “status quo,” as Jon Voight’s National Treasure character would say. It is at this point where who is right or who is wrong begins to take a backseat. It is also the point when the customer’s unique perspective on the problem at hand must be heard, understood, and respected.

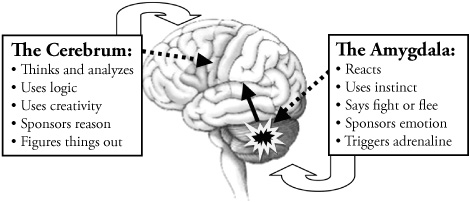

Figure 3. The Human Brain’s Cerebrum and Amygdala

Now, let’s take a deep dive into the psycho-logic of service recovery. We begin with a review of what you probably learned in ninthgrade general science or tenth-grade biology about the workings of the brain. The brain is divided into many parts. We will focus on two key parts—the cerebrum and the amygdala (see Figure 3). The cerebrum is that big grey wrinkly part that we typically call the brain. It is divided into two halves (or hemispheres)—the right side is the intuitive, creative side; the left is the logical, rational side.

What does the cerebrum do? In its entirety it is the seat of logic, creativity, analysis, insight, learning, and problem-solving. We humans have the largest cerebrum in relation to body weight of any species. In fact, the label Homo sapiens comes from the Latin meaning “wise or knowing man.”

And, the amygdala? From an evolutionary perspective, it is one of the oldest parts of the brain and controls instinct and a person’s physical reaction to danger. Sometimes referred to as the reptilian brain (or, with a hat tip to Seth Godin, the lizard brain), it controls the fight-or-flight response and triggers the secretion of adrenaline—the hormone that gets dumped into the bloodstream to make us faster, stronger, and tougher when threatened. Adrenaline is not stored in the brain, but it is the amygdala that flips the switch causing its release. It is what makes your hair stand on end and enables all your senses to be much sharper and keener in a crisis.

When you experience anything in life, imagine the message taking two routes. The slower route goes to the cerebrum; the faster route goes to the amygdala (refer to Figure 3). The amygdala is connected to the cerebrum and acts much like an early-warning clearinghouse for any signs of threat. If the amygdala senses danger, it quickly sends a message to the cerebrum requesting it to ignore the forthcoming message (the slower-moving information). With that warning, the cerebrum mostly shuts down—sometimes as much as two-thirds of it—in order to allow the amygdala to deal with the threat situation in a reactive or instinctive way. In other words, evolution has enabled the brain to let instinct rule over logic in times of threat or danger.

Imagine a cave man out on a leisurely stroll when he suddenly encounters a mean, angry saber-tooth tiger. If the cave man thought to himself, “Let me figure this out. Seems to me I recall my father telling me if I saw one of these animals I needed to move to the left, no wait, I believe it was move to the right,” what do you think would happen? He’d be lunch to the saber-tooth tiger. So, the brain learned that in saber-tooth tiger situations, we will live longer if the situation is dealt with instinctively and reactively, rather than logically and rationally.

The brain works today much like it did then. That is why, if your boss comes in and screams, “What the hell is this?” it is like a saber-tooth tiger to your brain and you find yourself getting suddenly very stupid. Actually, today it is not the threat of physical harm that triggers the amygdala’s taking over for the cerebrum; it is the threat of emotional harm, which can range in severity from mild disappointment to downright fury. The more the sense of harm moves to the fury end, the more “victim” the customer feels.

The path to getting a good connection is to remember the customer is not acting rational, but acting threatened. There is an old truism in psychology that states: anger is not a primary behavior, it is a secondary behavior. The primary behavior is fear. What we see on the outside might be anger; what is going on in the mind of the angry customer is fear. So, when your customer is very angry, ask yourself: “What is he or she afraid of?” Bottom line, it is the fear of being a victim.

What does being a victim really mean to a customer? It could mean many things: “I will look stupid,” “I will lose control,” “You will win and I will lose,” “I will lose now but I’ll lose even more next time.” You get the idea.

The point is, when people go into this state, they are not operating out of their normal thinking brain. They are operating out of the world of fight-or-flight—they want to fight or flee. They may appear to be acting practically insane. Actually, at some level, their irrational response is a type of temporary insanity. The logic of customer healing is to invite the person out of their “insane” state to a more rational state where effective and joint problem solving can occur. Think of the right-balancing goal as an invitation to partner.

Partners Soothe, They Don’t Defend

Imagine you are the parent of a small child who wakes up in the middle of the night frightened by a bad dream. In tears, the child comes into your bedroom. What would you do and say? The answer is easy—you would model bravery and confidence; you would carefully listen without judgment; and, you would offer great empathy as you seek to calm and encourage. The principles used for a small child with a bad dream are the same for customers with a bone to pick.

Angry customers feel victimized in some way. The source of the fury may vary. We all have our hot-button triggers hardwired to early experiences and learnings, albeit sometimes causing irrational beliefs. Regardless of what’s driving the customer’s sense of victimization, the response should demonstrate the complete absence or even hint of threat. The attitude reflected by the service provider should always be one that reflects the “3 Cs”—calm, confident, and competent. A calm attitude will help to reflect humility and the attitude you want from the customer. A confident attitude will soothe because in the tense early stages of recovery you want the customer to know you can handle their situation. A competent attitude is essential because you must not just fix the customer, you must actually be able to fix the problem.

Another essential in partner-like soothing is humility, our label for sincere compassion, authentic concern, and total vulnerability. Humility is crucial in the service provider’s response to an angry customer because it communicates “I am not your enemy.” It announces a kind of no-fight zone in order to calm the raging customer out of the “ready to fight” amygdala-driven mode. It begins with creating a connection that demonstrates sincere interest and obvious concern. Use open posture and eye contact. Listen to the customer and, equally important, look as if you are listening. Apologize with feeling. Avoid using we in apologizing to customers, as in “We’re sorry.” Apology should always be delivered in first-person singular: “I’m sorry.” “I’m sorry” doesn’t suggest you caused the problem or that you’re automatically the culprit. “I’m sorry” does mean, however, “I care.” It says you are not just passing along the sentiments of some anonymous or impersonal we looming in the background.

The tone chosen is equally important. Again, model the attitude you would like the customer to assume. As Abraham Lincoln said, “A person convinced against their will is of the same opinion still.” Assume innocence, even if you have prior history about this angry customer. Lower your voice. Let the customer witness genuine concern. If you are in a face-to-face recovery situation, look the customer in the eye. Be forthright and direct. There’s no need for a “tail between your legs” style. Things went wrong; the customer was disappointed. Acknowledge it honestly and frankly, and be ready to learn from it and move on.

Partners Understand, They Don’t Justify

It is important to remember that, before you can engage the customer in problem-solving, you must get them out of the part of the brain they are currently in (the amygdala) and into the part of their brain where problem-solving occurs (the cerebrum). The amygdala is telling them to get ready for a fight. The actions of the service provider need to signal that the customer’s defensive stance is not necessary. Humility begins to set the stage, but it is the search for understanding that causes the customer to shift from the fight-or-flight posture to problem-solving mode.

Empathy is an expression of kinship and a powerful partnering practice. It says to the customer that you are like the customer—not above or below. It means using words that communicate complete identification with the customer; that you fully appreciate the impact the service failure has had on them. It is like saying “I get it! I know just how much this hurts. I am in tune with where you are, and I would feel just like you do if this had happened to me.”

It is important to show confidence while demonstrating empathy. In other words, it is inappropriate for service people to wallow in bad feelings or demonstrate a “we goofed up big-time” sentiment. Remember, empathy is not synonymous with sympathy. Customers don’t want someone to cry with (sympathy or shared weakness); they want an understanding shoulder to cry on (empathy or the gift of strength).

Empathy communicates understanding and identification. It means listening to learn, not listening to make a point or to correct. Whether you as a service provider agree or disagree with the customer’s view isn’t the point. The goal is to give evidence that you understand. It includes agreeing with their feelings (not necessarily their position). Deal with feelings, before you deal with facts.

THE SERVICE DOCTOR SAYS

H Humility. Let customers hear your sincere concern. “I am so sorry…”

E Empathy. Let customers hear words that communicate “I can appreciate why you are upset.”

A Alliance. Let customers witness your sense of urgency. Offer a symbolic gesture of sorrow if appropriate.

L Loyalty. Let customers know you care by following up after a problem

Understanding customers in times of trial and tribulation includes getting insight into their expectations. If a solution or repair to the service covenant is in the offing, knowing the customer’s expectation for resolution is vital. A customer’s expectations can be as unique as the body shape and inner functioning a patient presents to a doctor. But just as in medicine, there are fundamental similarities that can guide our efforts. The basic likeness of two different human’s kidneys enables physicians to perform kidney surgery using a reliable set of norms, protocols, and prognoses. There is an apt parallel in service recovery expectations. We all want personalized treatment, but our individual visions of what that entails can share a lot of similarities. Think of your role as that of a service doctor.

Partners Include, They Don’t Impose

Assuming you have drawn the person out of the victim state, the customer is now more in a partnership position for joint problem solving. However, the reason we stay focused on a mutual discovery process is because the customer’s trust in you is still very tenuous and cautious. Therefore, to offer a solution can be less effective than finding a solution together. Alliance is the word we use for the type of partnershipdriven collective problem-solving required.

Alliances are formed through give and take. They are achieved through joint discovery. Language like “What would you suggest?” or “What would you like to happen next?” is more inclusive and less threatening than “off-the-shelf”—sounding solutions. Keep in mind this is about problem solving with a partner.

Alliance includes words and actions that tell customers they’re dealing with someone who has the moves and the moxie to fix their problem. They want can-do competence, attentive urgency, and a take-charge, “I’ll turn this around” attitude. Service failure first and foremost robs customers of the confidence they have in an organization, yet that confidence is quickly restored if customers observe you moving nimbly and confidently to address their problem.

If the infraction is major, forging an alliance may mean more than clearing up the “old debt.” It may be helpful to offer some type of atonement. Atonement involves providing some token or symbolic gesture that tangibly telegraphs your sincere regret that the disappointment occurred. Atonement does not mean “buying” the problem. It can be as simple as a small courtesy, a personal extra, or a value-added favor. Act responsible for their recovery and never duck the issue or pass the buck for someone else to handle.

Partners Care, They Don’t Control Damage

Assuming a solution is found and agreed upon, it is vital the customer witness something happening that communicates irrefutable proof that you can be relied on again. Healing service recovery includes loyalty, the after-the-fact experiences of the customer that communicate: “We are loyal to you. We will not abandon you now that we’ve solved your problem; this is not a one-time fix-and-forget.”

Service research shows that following-up with customers who’ve experienced problems is one of the most powerful steps you can take to cement a continuing relationship.2 Pick up the phone and call the customer to find out if everything is back to normal, or if there have been any continuing problems. Send the customer an email. For example, after a two-hour weather-related delay, Delta Airlines sent a short e-survey with questions specifically targeted at learning from the disappointing situation. Customers could choose which airport personnel to whom they directed their feedback (the departure city or the arrival city).

When the customer returns for future service, ask about the last problem. If customers know you remember and are still concerned, they’ll come to realize their bad experience was an exception. And, remember to always keep your promises. Service recovery starts with a broken promise (at least in the eyes of the customer). Don’t make a promise as a way to recover and then create doubled anger by disappointing the customer again.

![]()

Correcting a bad connection begins and ends with remembering you are a memory-maker. Memory making is about how we turn customer disappointment into customer delight; it is about how we transform an “oops” into an opportunity, turning a bad connection into a good one. Most of all, it is the recognition that the service covenant has been broken and must be repaired, not simply patched up.

A good electrician will tell you that bonding a bad connection is only effective when the repair is made stronger than the original. The same is true for service recovery. Research tells us that customers who have a problem and have that problem spectacularly solved will be more loyal than customers who have never even had a problem.3

Go to

To err is human! And, you cannot please everyone all the time. Tool #1 provides ways to deal with those uniquely challenging customers. Tool #10 can help you deal with that (we hope) very rare situation in which you have to part ways with a customer.

Think of it like this: before customers experience disappointment they operate purely on faith that all will go well. After they have experienced service breakdown followed by great recovery, they operate on proof—solid evidence that they have seen you at your worst and witnessed how effectively you right a wrong. This does not mean we want to create a problem just so we can fix it real good! It does mean that dealing like a great partner with customers at their darkest moment can be the most powerful part of memory-making.