CHAPTER 6

The Rise of Teams: Reinvent Organizations, from Individuals and Hierarchies to Teams and Networks

If your company has an excessively rigid internal structure and employees have a rigid mindset, they don't just miss dangers and miss risks, they also miss big opportunities.1

—Gillian Tett, editor and author, United States, The Financial Times; author, The Silo Effect

The last Apple org chart Steve Wozniak has seen shows that he still reports to Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. Not one to shy away from dark humor at the expense of Jobs, who passed away in 2011, Wozniak noted, “Since Steve died, I can't be fired.”2 Of course, Wozniak stepped down from Apple in 1985, and remains an employee in a ceremonial capacity only, something the org chart failed to capture. Organizational charts have long been the butt of jokes, in part, because they are rarely up to date, and even when they are, they generally fail to reflect reality. More significantly, they no longer represent the more dynamic organizational models that are evolving at many companies, based not on individuals jockeying to edge their way up to the top spot, but, rather, on teams, networks, and platforms working together.

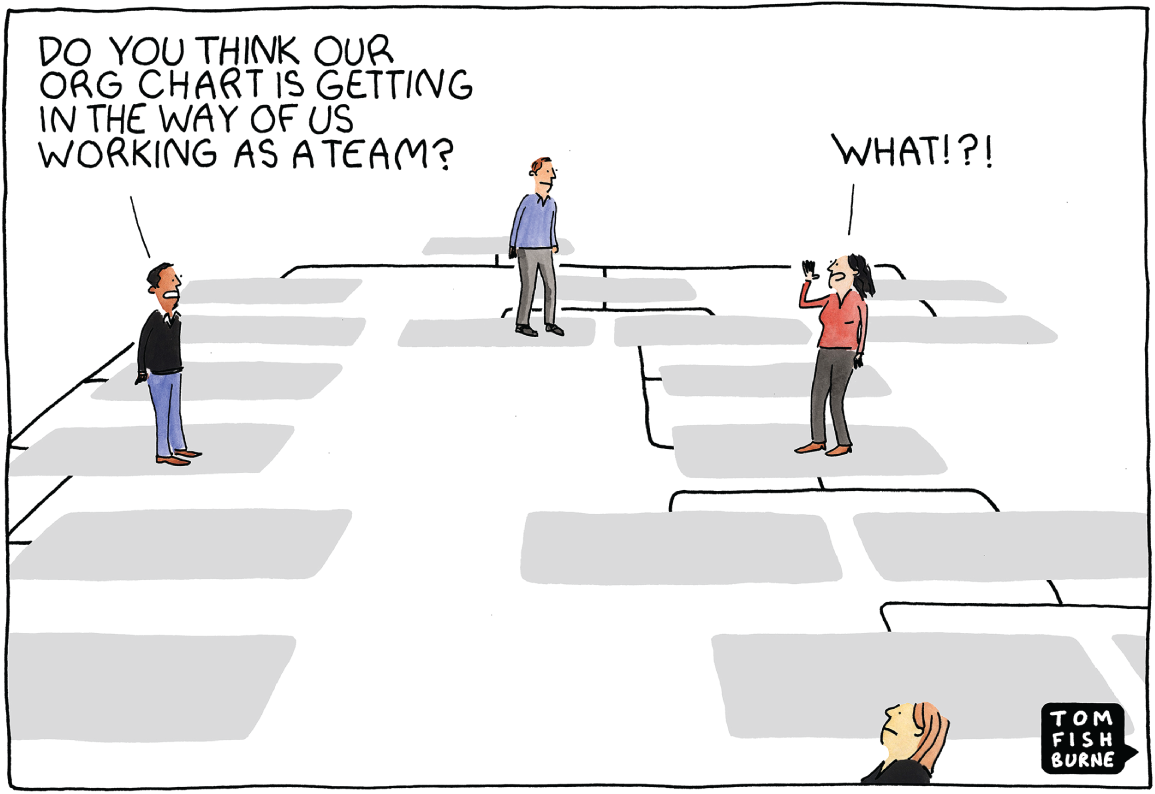

It is easy to picture the traditional org chart, with its branches, sticks, and boxes cascading down from the CEO, who sits at the crown. At their best, org charts offer a visual representation of who is below us, who is above us, and how employees and leaders fit into the hierarchy of the entire company. At their worst, they reinforce the drive to the top, even if it means working solo to get ahead and forgoing teamwork. Org charts reflect a time when companies were built around silos and scale efficiencies, and designed solely for steadiness, predictability, and efficiency. Organizations were also structured around accountability, with clearly defined jobs that fit within a hierarchical structure. Who do I report to? Who does my boss report to? These questions could easily be answered. Traditional organizations performed well in a world of stability but that is not our world today.

Static org charts are becoming artifacts of the past. We are now using advanced analytics to visually represent the team dynamics of how people actually work. New designs are emerging that embrace natural connections and configure multidisciplinary teams to deliver value more effectively.3 Today, most work is not done in functional silos but in teams or ecosystems, which are networked teams connecting organizations. Newer organization models are flatter and are ordered around projects, relationships, and information flows.

One of the fathers of the org chart and the person responsible for shaping the way we think about the traditional corporation is Alfred Chandler, the influential Harvard Business School professor and business historian who wrote extensively about the scale and management structure of large business enterprises. Chandler believed in the role of hierarchies and the importance of managers in the rise of corporations. He famously wrote in the 1970s that “structure follows strategy,” emphasizing that all aspects of an organization's structure, from the creation of departments to the reporting relationships, should be designed with the company's strategic execution in mind.4

Organizing work around hierarchies and bureaucracy dates back to the early nineteenth century when offices were introduced in the East India Company, the first joint stock company. The structure reflected predictable workflows in which clerks and accountants moved paper to process transactions and generate managerial and financial reports.5 As work has shifted from processing transactions, which increasingly can be handled by machines, to solving problems and relationship-based work, we no longer need massive transactional bureaucracies as our default organizational model.

Organizations no longer need to be structured around control, with senior people at top of the hierarchy telling people below what to do. Increasingly decentralized models are moving away from primarily functional structures and embracing networks of teams inside and outside the organization. Networks of teams allow people to move from team to team—and project to project—rather than remain within a rigid or static configuration. Teams are assembled around a product, market, or integrated customer need and not necessarily a business function. Organizational strategies are moving beyond direction, control, and execution to building culture, common purpose, and ways of working to share information, to work within and across teams, and to promote collaboration in multiple directions.

The coronavirus pandemic taught us that advances in technology can facilitate collaboration across and within teams despite operating from disparate physical locations. Changes already underway have sped up, making some question the future role and location of offices. Though it is too soon to know the fate of office spaces, it is clear that the shift to collaborating virtually, across teams, across ecosystems, across functions, and across the globe, is gaining momentum.6

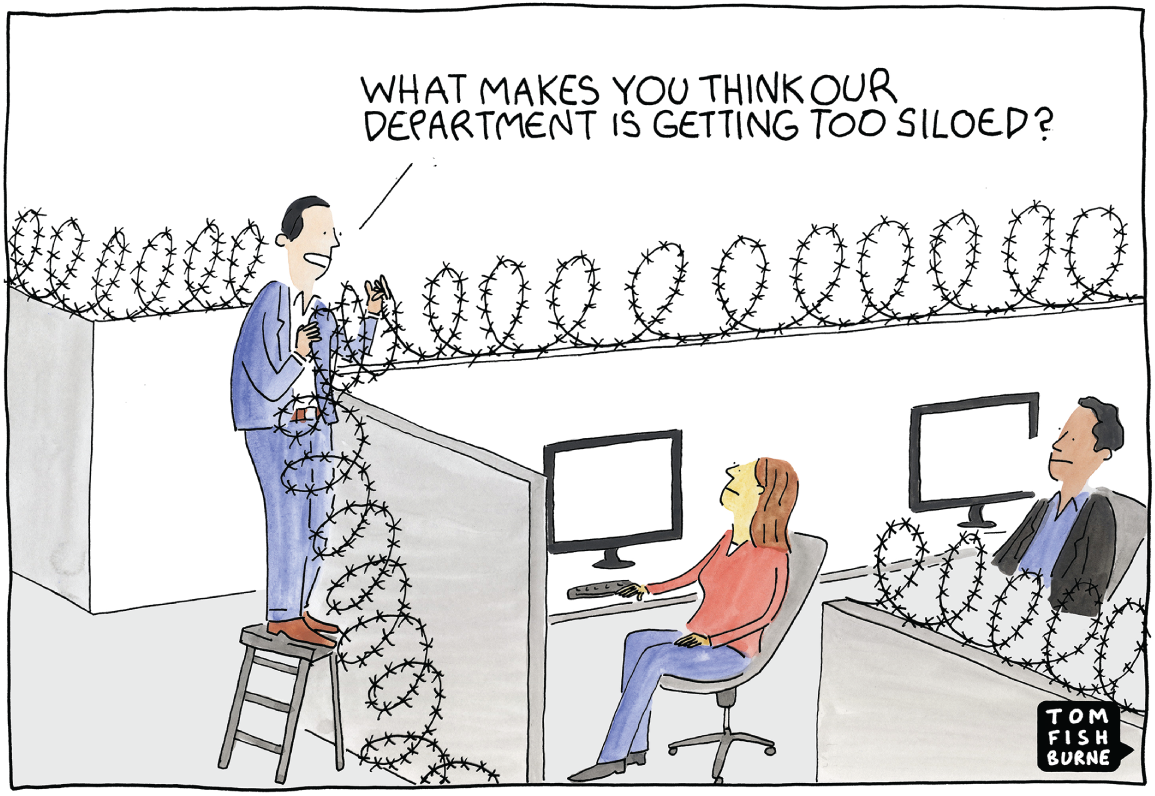

The silo effect occurs when different departments or teams within an organization fail to communicate, and undermine productivity as a result. Two departments could be working on the same initiative, or at cross purposes, without knowing it.

Silo Busting

The opposite of working collaboratively is working in silos. The silo effect occurs when different departments or teams within an organization fail to communicate, and undermine productivity as a result. Two departments could be working on the same initiative, or at cross purposes, without knowing it. Financial journalist and author Gillian Tett has studied silos within companies, finding that their internal structures, the complexity of their businesses, and regulation often reinforced siloed approaches and the associated turf battles. Her research explored the aftermath of the financial crisis, when many financial institutions realized that one of the factors that caused the crisis was their siloed nature.

“The right hand didn't know what the left hand was doing,” Tett said in our interview. She noted that both the Bank of England and many major financial institutions had silos that blinded them to the impending collapse of major parts of global financial markets—or at the very least made it harder to see and act on. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, there has been a drive across the financial sector to operate in more holistic and integrated ways. Tett has dubbed the effort for departments in a company to shift away from behaving as isolated islands “silo busting.”7

Some siloes arise as a result of the way organizations are structured and regulated. They can also arise when we put on blinders or lose perspective, Tett said. In her book The Silo Effect, she explores the consequences of companies operating with excessively rigid internal structures and rigid mindsets “where tribes end up killing each other and competing.” Tett explains, “siloes can exist on several levels. You can get structural siloes where companies are identified into nutty divisions or departments that try and kill each other. You can get cognitive siloes where different people are essentially trapped into tunnel vision by having very rigid ways that they divide up the world. And then you get social siloes, people basically only ever talking to people like themselves (tribalism). In some ways the social siloes are an increasing problem.”8

She notes that as the result of these different types of silos, companies miss not only dangers and risks, but also big opportunities. “The world moves on outside their company and they end up essentially not seeing how different categories are collapsing [outside the company], like, say, hardware, software, and content at the time of the death of the Sony Walkman and the move into digital music,” Tett said. “That's why Sony lost out in positioning their Walkman. [To win] you need to … think about how the world's moving outside but look at your own structures and mental taxonomies as well.”9

Tett trained as a social anthropologist She is a proponent of finding new ways for us to look at ourselves and to consider how our organizations operate—as though we were outsiders instead of insiders. She notes that a fundamental principle of anthropology is that it's very hard for us to truly see our environment until we step outside of it.10

“Learning to look at yourself afresh through someone else's eyes is one of the most powerful tools that you can use to see your taxonomy,” she notes. “It's what we live every day. It's how our minds are shaped. It's like asking a fish to think about water. Because you know, they're just in it. They can't see it. So we all think it's entirely natural to put sales in one department, marketing in another, IT in a third department, but is it?” A key feature of the new structure is to move beyond the silos and tunnel vision that have existed in large corporations and toward improved information sharing and greater connections between teams.11

Tett challenges us to think about three questions. First, what is the taxonomy that we hold in our heads to sort out the world and the work structure? How we classify the world, and the boundaries we envision, matter enormously—although we tend not to think about them because we take them for granted. Second, what are the structures and classification systems we need to get work done? These include our functions, divisions, and silos. Third, are we constantly challenging ourselves to be aware that the organizational constructs we create to get work done are exactly that—constructs? We need to make sure that we do not become victims of our silos but, instead, that we are able to master them. As Tett summed up, “today's teams need to be porous and cross boundaries.”12

In the 1800s and early 1900s, the CEO delegated responsibility to functional managers. This model was later extended to include specialists, each with their own domains, such as the chief financial officers, chief information officers, chief human resources officers, each working independently. However, our complex and dynamic world often presents challenges that no single function can address, calling upon organizations to work across functions. These challenges have led to a redesigning of organizational structures to integrate robotics and artificial intelligence technologies, as well as to capitalize on new employment models, such as gig workers and crowds, across industries and functions.

The Rise of Networks of Teams

A key building block of the new market-oriented ecosystem is the role of teams. As teams work together on specific projects and challenges, they form networks. These networks of teams can join forces to tackle larger projects, then disband and move on to new assignments once the project has been completed. Increasingly, companies are using internal talent marketplaces that allow employees to self-select and sign up for projects and teams that they would like to join. For example, at NASA, a talent marketplace allows employees to access a range of internal projects and career development opportunities. As work moved into teams, we can identify three archetypes of organization teams: configurable teams (grouped around a project); production lines, assembly lines, distribution centers, and warehouses; and teams from across ecosystems, in which the project may be the entire company, as in making a commercial movie or theater production.

Thomas Malone, an organizational theorist and professor at the MIT Sloan School, and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon have explored the extraordinary value of teams in their paper, “What Makes Teams Smart.” Malone has made the distinction between intelligent individuals and intelligent teams. Though we might assume that smart people make smart teams, his research points to three critical attributes of exceptional teams: social perceptiveness, democratic participation, and the number of women on the team. He suggests that a team's collective intelligence is a stronger predictor of team performance than the ability of individual team members. Collective intelligence includes a group's ability to collaborate, coordinate, and get things done.13

Research by Deloitte has found that it is not only individual employees who need to collaborate effectively but managers and leaders as well. Rather than behaving as independent functional experts, the C-suite must operate as a team, or as a “symphonic C-suite.” An organization's top executives play together interdependently as a team while also leading their own functional teams. This approach enables the C-suite to understand the many impacts that external forces have on and within the organization—not just on single functions—and formulate coordinated, agile responses.14

Team-Based Thinking

In the past several years, Deloitte's annual Global Human Capital Trends report has explored the shift from hierarchies to cross-functional teams that move beyond divide-and-conquer models. In 2019, “Organizational Performance: It's a Team Sport” showcased leaders and teams working together to solve multidisciplinary problems, not to just process and execute transactions. The research showed that adopting team structures improves organizational performance. High-performing organizations promote teaming and networking. Although they have many senior leaders and functional departments, they are able to move people around rapidly, spin up new initiatives quickly, and can start and stop projects at need, moving people into new roles to accommodate.15

To tackle these challenges, organizations need to adopt team-based thinking internally as well as in the broader ecosystem in which today's social enterprise finds itself. To help accomplish this, there are five layers in which team-based thinking should be embedded:16

- The ecosystem. How the work environment is orchestrated and connected: Adaptable organizations exist in purpose-driven ecosystems with defined customer-focused missions.

- The organization. How work is configured: Away from deep hierarchy and silos toward a network of multidisciplinary teams.

- The team. How work is delivered: High-performing teams adopt connected ways of working and an adaptable culture.

- The leader. How work is led and managed: Leaders are inclusive orchestrators versus technical task masters in order to unlock the full potential of diverse capabilities, experiences, personalities, and skills.

- The individual. How work is executed: By unleashing resilient individuals through adaptive talent programs so that people can learn and develop not by “climbing the ladder” but by growing from experience to experience.

Stanley McChrystal's book, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, is a manual for leaders looking to make their teams more adaptable, agile, and unified in the midst of change. McChrystal, a retired U.S. Army general, lays out the many ways large organizations can benefit from the agility of smaller teams. He writes that hierarchical management techniques no longer work because organizations are too large for any one person to make all the decisions. The military uses a management style in which your team operates as a network with a shared consciousness; every member is empowered to execute. McChrystal says that organizations need to share information and build genuine relationships and trust.17 He believes that leaders should behave like gardeners. “You are not playing a game of chess where you dictate every move,” he said. “You create an environment where every piece can simultaneously grow like a gardener.” 18

Human–Machine Teams as Superminds

Working as teams extends from colleagues and leaders to teams of people with machines. MIT's Thomas Malone offers a framework for achieving new forms of human–machine collective intelligence. In his book Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together, Malone defines a “supermind” as a group of individuals, and increasingly with computers, acting collectively in ways that seem intelligent.19

Every company in the world is a supermind, Malone says. So is every democracy, army, neighborhood, scientific community, and club. Realizing this can get us thinking about how we are “in this together,” and how we can make our superminds smarter. “Superminds have been around at least as long as people have, and when you learn to recognize them, you realize they run our world,” Malone says. “Almost everything we've done has been done by superminds.”20

Malone identifies five different types of decision-making superminds: hierarchies, markets, democracies, communities, and ecosystems. This is interesting in part because we tend to think that organizations—superminds—make decisions through hierarchies. Recognizing the different types of decision-making provides us with new ways of thinking and approaching how we “organize” work and collective efforts for new and different results. Once you start thinking about these five types of decision-making, you see their usefulness in different situations—and you see their application everywhere.21

- Hierarchies. In a hierarchy, you follow your boss's orders. Decisions are made by delegating them to specific roles and members in the group.

- Markets. In markets, decisions are based on mutual transactions. Group decisions are the sum of all of the pairwise agreements made between buyers and sellers.

- Democracies. In a democracy, group decisions are made by voting or polling.

- Communities. In a community, you are enabled and constrained by the community's norms. Group decisions are based on a kind of informal consensus based on norms and reputations.

- Ecosystems. In an ecosystem, group decisions are made by the law of the jungle (whoever has the most power gets what they want) and the survival of the fittest.

Malone's view of ecosystems underscores an interesting point relative to the term ecosystems. The word is often used to describe organizational strategies where the focus is on group dynamics beyond the organization or enterprise. Tett, talking about silos, and Malone, talking about superminds, both focus our attention on the importance of boundaries and connections, and the mental models we bring to the table in applying these ideas.

The increasing pace of contextual change means that organizations must also change or die.

Market-Oriented Ecosystems

The primary drivers of organizational evolution are increasingly fast-changing and unpredictable environments, especially those created by technological breakthroughs. When change was predictable, traditional organizational hierarchies were able to support centralized decision-making through functional silos to produce organizational efficiency. However, in our whitewater era of exponential change, traditional organization models fall short.

David Ulrich and Arthur Yeung, in their book Reinventing the Organization, describe the context in which organizations increasingly find themselves as volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, or VUCA. The authors describe a new model for the twenty-first century that they characterize as a market-oriented ecosystem (MOE), in contrast to traditional hierarchies. Yeung, a senior management advisor to Tencent Group, and Ulrich, a professor at the University of Michigan's Ross School of Business, view the evolving organization as a market-oriented ecosystem comprising many forms of collaboration and alliances. “I think that the mental model of an organization as a control system has basically got to shift,” Yeung notes. “There's an evolution of the organizational species from hierarchy to systems to capability to MOEs—market-oriented ecosystems,” said Ulrich in our interview.22 To survive and thrive in the era of technological disruption, organizations need to be designed for agility, innovation, and customer centricity. “The increasing pace of contextual change means that organizations must also change or die,” Ulrich says. As companies strive to become more agile, they are shifting their structures from traditional, functional models to interconnected, flexible teams.23

Yeung said that Tencent is a good example of a market-oriented ecosystem in action. One of the largest companies in China, and the world, Tencent is a social media company and a venture capital and investment firm with holdings in hundreds of companies across media, e-commerce, and gaming. “Structurally, it follows the organizational principle of a platform, plus business teams, plus ecosystem partners,” Yeung said. Tencent is able to connect to more than 1 billion active users. This is the core platform that feeds user traffic to all business teams, including online games, music, and videos.24

To enrich its product and service offerings, Tencent also develops close partnerships with a large number of ecosystem partners that are able to offer services in dining, transportation, shopping, movie ticketing, food delivery, and even paying taxes or traffic tickets, Yeung says. “They connect into WeChat—a large messaging, social media, and payments system,” Ulrich says. “They begin to know what consumers want. They get into JD.com, which is China's largest on-line retailer. And so the knowledge from WeChat (social media) can transfer to what JD.com (on-line retail) can do.” Tencent offers an example of an agile organization that is designed to move quickly and is built on connections and extending the reach of an enterprise, through platforms, to a broader ecosystem.25

The leader's job at Tencent is not about what they control but how they empower others, Ulrich says. “The traditional mental model of an organization is about power. It's about control. It's about clarifying decision rights. In the MOE organization, it's more about agility, customer, innovation and moving to penetrate market opportunities. I think that mental models of organizations as control systems have basically got to shift.”26 In terms of operating governance, Tencent uses a market-oriented mechanism to govern the relationships between its core platform and business teams, across and among business teams, and between the platform and its ecosystem partners. “Instead of spending a lot of time in internal coordination and negotiation, Tencent creates mechanism for these teams to share revenue or credit through agreed protocols,” Ulrich says. “This ensures the efficiency of resource allocation so that the best products or services will get the best resource support inside and outside Tencent ecosystem.”27

The biggest challenge for leaders when reinventing organizations is a liability of success, Ulrich notes. “When an organization or individual succeeds, they tend to lock into what worked and try to replicate it rather than continue to evolve it.” Leaders need to let go of their past assumptions and take a leap into this new organization logic. To help leaders make this leap, Ulrich and Yeung highlight several key questions to be answered by leadership teams:28

- Do we really need deep changes in our organizational model? Will we be left behind if we cannot innovate or change fast enough to today's disruptive environment?

- What will be the desired organizational model? Will the MOE model of platform plus business teams plus ecosystem partners work for us? Or does traditional hierarchy or other organizational models make more sense for us?

- How can we migrate from our current organizational model to the desired organizational model? What are the key steps required to lay out a practical roadmap for diagnosis and improvement actions?

- How do we increase the chance of success? Conviction and confidence of the leadership team is critical along the transformation journey. Resources need to be invested to make things happen. Tough decisions in business, organization, and people need to be made. Make sure to effectively communicate to all levels of the organization to keep multiple stakeholders informed and engaged.

- What are the implications for business leaders of the new model? What behaviors and experiences will twenty-first-century leaders need to have to effectively lead market-oriented ecosystems?

Agility and Adaptability for Resilience

Building agile teams and adaptable organizations are critical for success in the dynamic future world of work. If there are three terms extensively used to described future organization strategies, teams, and ecosystems—which we have discussed earlier—agile is at the top of the list. The term agile was popularized in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, published in 2001, which created the agile movement.29 These ideas have been moving beyond the software and technology corridors for the past decade, but it is useful, given the importance of the concepts behind agile, to revisit its origins.

Agile started as a movement in software almost 20 years ago. In response to the accelerating rate of change in technology—including processing power, then cloud computing and AI—traditional methods for developing and implementing technology solutions and systems were too slow and cumbersome. These models were generally described as “waterfall” methods that organized software projects into linear and sequential phases: requirements gathering, design, development, implementation, security, and support. In a world in which business was more stable and predictable, waterfall projects, which could take years to complete, were effective and successful. Companies would implement a system with the expectation that it would last years—or decades. As the pace of technological innovation continued to speed up, these linear and sequential models, which effectively “froze” requirements once the development of a project started, were not suited for the timeframes and expectations that software and technology teams were challenged to meet. Enter the agile manifesto and movement.

Agile involves approaches to software and technology focused on speed, integrated project teams, iterative design and delivery, customer focus, and collaboration and learning. Early on, agile teams connected design, development, and operations into an approach called DevOps. Then security got in the mix, as it should have from the start, and we saw DevSecOps. The goal was to gather the players in a product on a small, agile team that could collaborate fast, to create a working version—not just prototype—of a technology solution or product. Agile teams developed their own language and routines—like having daily stand-up meetings with all team members to make sure the team was working quickly, moving past obstacles, and getting things done. Another key principle of agile development is the idea of focusing development and delivery on a minimally viable product (MVP). The goal was not to develop a perfect, idealized, version of a product with all the bells and whistles but to get a product that worked and met customer requirements uniquely, out the door as fast as possible. Improvements could be made later on.

The future is being driven by fast changing contexts and technology. Many companies have changed the way they structure and do the work of IT around agile methods and teams. The challenge for us going forward is to build on the experiences and lessons of agile in the technology and software world and ask the question: How do we build agile, adaptable, and resilient organizations for the work that lies ahead? We have an idea of what the future looks like; it is organized around teams, networks, and platforms, not as a hierarchy. It is organized around collaboration and distributed decisionmaking, not around centralized command and control. It is organized around responsiveness and constantly changing customer and environmental challenges, not around a world of predictability and scale. The future of work is built for change. It is resilient by design.

Notes

- 1 Tett, Gillian, interview with Suzanne Riss and Jeff Schwartz, February 2020.

- 2 Shinal, John. “Steve Wozniak Is Still on Apple's Payroll Four Decades after Co-Founding the Company.” CNBC, January 18, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/01/18/steve-wozniak-still-on-apple-payroll-jokes-he-still-reports-to-jobs.html.

- 3 Rahnema, Amir, and Tara Murphy. “The Adaptable Organization Harnessing a Networked Enterprise of Human Resilience.” Deloitte, n.d. https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/human-capital/articles/the-adaptable-organization.html.

- 4 Rhodes, Mark. “Strategy First … Then Structure.” Blog: Strategic Planning. Free Management Library, January 23, 2011. https://managementhelp.org/blogs/strategic-planning/2011/01/23/194/.

- 5 Nixey, Catherine. “Death of the Office.” The Economist, May 5, 2020. https://www.economist.com/news/2020/05/05/death-of-the-office.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Tett, Gillian. The Silo Effect: The Perils of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- 8 Tett, Gillian, interview.

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 “What Makes Teams Smart.” MIT Sloan Management Review, October 4, 2010. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/what-makes-teams-smart/.

- 14 Brodie, John. “The Symphonic C-Suite: Teams Leading Teams.” Deloitte, n.d. https://www2.deloitte.com/za/en/pages/human-capital/articles/the-symphonic-c-suite.html.

- 15 Volini, Erica, Jeff Schwartz, and Indranil Roy. “Organizational Performance: It's a Team Sport 2019 Global Human Capital Trends.” Deloitte Insights, April 11, 2019. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/human-capital-trends/2019/team-based-organization.html.

- 16 Ibid.

- 17 McChrystal, General Stanley, Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York, NY: Penguin Publishing Group, 2015.

- 18 Gordon, Beau. “Key Takeaways from Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal.” Medium, March 27, 2017. https://medium.com/@beaugordon/key-takeaways-from-team-of-teams-by-general-stanley-mcchrystal-eac0b37520b9.

- 19 Guszcza, Jim, and Jeff Schwartz. “Superminds: How Humans and Machines Can Work Together.” Deloitte Review, no. 24 (January 28, 2019). https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/technology-and-the-future-of-work/human-and-machine-collaboration.html.

- 20 Ibid.

- 21 Malone, Thomas W. Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together. New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2019.

- 22 Ulrich, David, and Arthur Yeung, interview with Jeff Schwartz.

- 23 Ibid.

- 24 Ibid.

- 25 “How Companies Like Google and Alibaba Respond to Fast-Moving Markets.” Harvard Business Review, April 8, 2020. https://hbr.org/podcast/2019/10/how-companies-like-google-and-alibaba-respond-to-fast-moving-markets.

- 26 Ibid.

- 27 Ulrich and Yeung, interview.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Nyce, Caroline Mimbs. “The Winter Getaway That Turned the Software World Upside Down.” The Atlantic, December 8, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/12/agile-manifesto-a-history/547715/.