The online video market is very large, but it doesn't work like a "mass market." In this chapter, you will learn what journalists can teach marketers about marketing. You will also learn who discovers, watches, and shares new videos; what categories or types of new video they watch; when they discover new videos; where they share new videos, why few new videos go viral; and how video marketing works. Finally, you will learn that it's okay to admit, "I still don't have all the answers, but I'm beginning to ask the right questions."

Chapter Contents

Broadcast Yourself?

Five Ws and an H

So, how does YouTube work (Figure 2.1)? Why does it work? What can veteran marketers and new YouTubers accomplish by using it?

If YouTube were simply a new television network, then video marketing would be simple. You could simply apply all the old mass marketing techniques that you learned in college to a new medium. However, YouTube doesn't work like a television network, despite its slogan, "Broadcast Yourself." It works like a video sharing site.

Mass marketing assumes a large number of individuals watch the same video at the same time. Everett Rogers, in Chapter 8 of his book Diffusion of Innovations, calls this model of communication "the hypodermic needle model." It presumes that the mass media has "direct, immediate, and powerful effects on a mass audience."

However, video marketing uses what Rogers calls "the two-step flow model." In the first step, opinion leaders use a video sharing site to discover videos uploaded there. In step two, opinion leaders share videos they like with their followers. While the first step involves a transfer of information, the second also involves the spread of interpersonal influence.

Most of us didn't learn how video sharing sites work in college. We didn't learn why they work. And we're still trying to figure out what can be accomplished by using them.

That's why this book is about video marketing as well as YouTube. However, before we can tackle video marketing, you must (as Yoda would say) "unlearn what you have learned" about mass marketing.

In Chapter 1, I mentioned the role my kids played in helping me learn how YouTube works. In this chapter, let me share the role that my dad played in helping me learn how marketing works.

My dad was the director of marketing for Oldsmobile. Coincidentally, he was the director of marketing in the 1980s when Oldsmobile launched the ad campaign that claimed, "It's not your father's Oldsmobile."

When my dad graduated from college in the 1950s, television was changing the media landscape of his generation. As a marketer in the mass media era, he learned the importance of focusing on product, price, place, and promotion. When I graduated from college in the 1970s, newspapers were setting the political agenda of my generation. As a journalist in the Watergate era, I learned the importance of asking who, what, where, when, why, and how.

In the 1980s, I moved from journalism into public relations, and my dad saw this as an opportunity to start a conversation between peers, since public relations was part of marketing. One of the things we discussed was the difference in perspectives between marketers and journalists. Marketers focus on the four Ps of the marketing mix: product, price, place and promotion. Journalists ask the five Ws and an H for getting the full story about something: who, what, when, where, why, and how.

Table 2.1 compares these two paradigms.

Table 2.1. Marketing and Journalism

Classic Marketing | Classic Journalism |

|---|---|

Product | Who What When |

Place | Where |

Price | Why |

Promotion | How |

Classic journalism has the added advantage of this poem, found within Rudyard Kipling's story The Elephant's Child, to validate its point of view:

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

My father and I quickly recognized that marketers weren't focusing on two fundamental questions that journalists were asking: who and when. As we kicked this around, we both had some pretty powerful insights.

The reason classic marketing didn't focus on "Who" was it was actually "mass marketing." It assumed that everyone was a prospect for products that were mass produced. That may have worked in 1909 when Henry Ford said, "Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black." But it stopped working in 1924, when Alfred Sloan unveiled GM's famous market segment strategy of "a car for every purse and purpose."

My dad understood the power of market segmentation and recognized the importance of adding a fifth P to the marketing mix: the prospect.

"When" was another blind spot for mass marketing. My dad had started his career in the auto industry during the era of planned obsolescence. Each and every fall, a new line of cars was introduced—whether they featured cosmetic changes or fundamental improvements.

In contrast, I was starting a new career in the computer industry during an era when the price/performance of microprocessors was doubling every 18 months. I understood the power of Moore's Law and recognized the importance of adding a sixth P to the marketing mix: the pace of change.

Our conversations helped prepare me for what came next: In 1989, I became the director of marketing for PC Computing. Coincidentally, the magazine's publisher back then was Michael Kolowich, and one of our inside sales representatives was Suzie Reider. Kolowich, who is now president of DigiNovations, shares some of his observations later in this chapter and in one of the case studies in Chapter 11. And Reider, who is now the director of ad sales at YouTube, shares one of her presentations later in this chapter and wrote the forward for this book.

When I joined the magazine, we conducted some market research on how the readers of PC Computing informally influenced the purchase of innovative PC products and applications by their colleagues at work and friends in their neighborhood. We called our magazine's readers PC Champions.

When I presented our findings to an advertiser in Silicon Valley, she surprised me by asking, "Have you read Diffusion of Innovations by Everett Rogers?" I hadn't, so she lent me her copy of her marketing textbook for a graduate-level course at Stanford University. I was blown away.

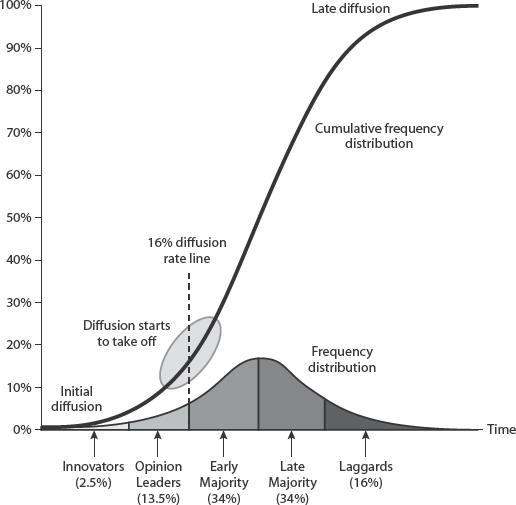

Rogers segmented markets by combing who and when into earlier adopters and later adopters of innovations. As Figure 2.2 illustrates, diffusion forms an S-shaped curve when you looked a cumulative adoption or a bell-shaped curve if you looked at adoption per time period.

Figure 2.2. The S-curve and bell curve. (Although this image is adapted from ones in Diffusion of Innovations, it captures many of the key findings in the book.)

I had seen markets segmented into the classic pyramid—with a few big customers at the top and lots of little customers at the bottom. But Rogers turned this point of view on its side. The most important customers weren't the biggest ones on the top of the pyramid; the most important customers were the early adopters on the left side of the S-curve.

Even more important, his two-step flow model introduced a new dynamic into the process of deciding whether or not to adopt an innovation. Rogers showed that, in addition to the big brands communicating to the mass market through the mass media, the individual members of diffusion networks are also communicating with each other.

The most important people in these peer-to-peer conversations are opinion leaders. According to Rogers, "The diffusion curve is S-shaped because once opinion leaders adopt and begin telling others about an innovation, the number of adopters per unit of time takes off in an exponential curve."

And his two-step flow model implied that the mass media were neither as powerful nor as directly influential as had previously been thought. He said, "Mass communication channels are primarily knowledge creators, whereas interpersonal networks are more important in persuading individuals to adopt or reject."

Now, video marketing is far more complicated than just two steps. But the two-step flow model illuminates the two blind spots that cannot be seen while looking forward or through either the rear-view or side mirrors of mass marketing: who and when.

So, let's apply the five Ws and an H to the online video market to ensure that we getting the full story about video marketing. Let's ask the following questions:

And, as Bette Davis warned in All About Eve, "Fasten your seatbelts; it's going to be a bumpy night!"

There's lots of data on who watches online video.

For example, comScore Video Metrix reported that 145 million viewers in the United States watched online videos in February 2009, which was 76 percent of the total online population in America. In Canada, 21 million viewers watched online videos that month, which was 88 percent of the total online population.

In the United States, the online video audience watched 13.1 billion online videos in February 2009, an average of 90 videos per viewer. In Canada, the online video audience watched more than 3.1 billion online videos that month, an average of 147 videos per viewer.

On October 3, 2008, the eMarketer Daily newsletter featured an article titled, "Where Is Online Video Headed?" As Figure 2.3 illustrates, eMarketer foresees the number of U.S. online video viewers—defined as individuals who download or stream video (content or advertising) at least once a month—growing to 190.0 million in 2012.

Now, this would be a mass marketing opportunity of Olympic proportions if audiences in the social media era sat down in front of their computers to watch online videos the same way that audiences in the mass media era sat down in front of their televisions to watch TV shows. But times have changed. Back in 1978, the vast majority of television viewers in the United States were watching one of just three TV channels during primetime: ABC, CBS, or NBC. As of April 2008, the vast majority of online video viewers were watching one of the 3.75 million user channels on YouTube alone.

More important, the process of discovering new content and sharing it with others has also shifted dramatically.

Forty years ago, there were only a handful of new TV shows each week worth talking about around the water cooler at work or over the phone at home. So the odds were good that anywhere from a third to a half of your colleagues and friends had also seen the new TV show last night. Although the rest of those who listened to the conversation couldn't rush home and watch a rerun back then, some might tune in the following week. There was a social component to mass media, but it was often indirect, delayed, and limited.

Today, there are around 15 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute. If the average video is 3.5 minutes long, then more than 250 videos a minute, 15,000 an hour, 360,000 a day, or 2,520,000 a week are being uploaded to the leader in online video. Nobody can watch even one in a thousand. That's why discovering and sharing a video has such an impact.

When you send a new video by email to your colleagues in the office or post it to MySpace for your friends to see, the odds are very good that nobody else in your social network has seen it yet. And they can watch it without delay and then relay it quickly to their other social networks. And so on, and so on. So, social media has a direct, immediate, and powerful impact on a mass audience.

As Rogers wrote, "The hypodermic needle model postulated that the mass media had direct, immediate, and powerful effects on a mass audience." However, he observed, "the mass media were neither as powerful nor as directly influential as had previously been thought." This led him to conclude that the hypodermic needle model was "too simple, too mechanistic, and too gross to give an accurate account of media effects. It ignored the role of opinion leaders."

One of the right questions to ask is not necessarily, Who watches online videos? One of the right questions to ask is, Who are the opinion leaders in the online video market?

The only market research I've seen that even begins to ask the right questions was conducted by the Pew Internet & American Life Project. The findings were made public on July 25, 2007, in an online video report written by Senior Research Specialist Mary Madden (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Online Video Gets Social: How Users Engage (Percentage of Video Viewers Who Do Each Activity)

Activity | Total | Men | Women | 18–29 | 30–49 | 50–64 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Receive video links | 75% | 75% | 75% | 76% | 77% | 71% |

Send video links to others | 57 | 59 | 54 | 67 | 55 | 45 |

Watch video with others | 57 | 58 | 57 | 73 | 58 | 34 |

Rate video | 13 | 15 | 10 | 23 | 11 | 4 |

Post comments about video | 13 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 9 | 5 |

Upload video | 13 | 16 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 5 |

Post video links online | 10 | 12 | 9 | 22 | 7 | 2 |

Pay for video | 7 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

[a] Source: Pew Internet & American Life Project Tracking Survey, February 15–March 7, 2007 | ||||||

One of the key findings was this: "The desire to share a viewing experience with others has already been a powerful force in seeding the online video market. Fully 57% of online video viewers share links to the videos they find online with others. Young adults are the most 'contagious carriers' in the viral spread of online video. Two in three (67%) video viewers ages 18–29 send others links to videos they find online, compared with just half of video viewers ages 30 and older."

Now, 57 percent of online video viewers can't all be opinion leaders. If they were, then every Don Quixote would have only one Sancho Panza as a follower. So, sharing links to the videos they find online with others is a necessary but not sufficient condition of opinion leadership.

According to the Pareto principle, which is also known as the 80-20 rule or the 90-10 rule, no more than 10 to 20 percent of online video viewers should be opinion leaders. Rogers also observed that "the S-shaped diffusion curve 'takes off' at about 10 to 20% adoption, when interpersonal networks become activated so that a critical mass of adopters begins using an innovation."

We need to dig deeper into the Pew report to discover other social behavior that would be "just right" to identify opinion leaders: "Video viewers who actively exploit the participatory features of online video—such as rating content, posting feedback or uploading video—make up the motivated minority of the online video audience. Again, young adults are the most active participants in this realm." The findings from the Pew report are as follows:

- Nineteen percent of video viewers have either rated an online video or posted comments after seeing a video online.

Madden wrote, "One of the features popular on many video sites is the ability to rate or post feedback about the content on the site. For instance, during the now legendary run of Lonelygirl15 videos on YouTube, viewers used the comments field to debate the authenticity of the diary-style videos in which the young girl shared her thoughts and daily drama with the world." If you look at the Pew rating and commenting data separately, 13 percent of video viewers have rated video, and the same percentage posted comments after viewing video online. Unsurprisingly, those who engage with online video by rating and commenting tend to be young; video viewers ages 18 to 29 are twice as likely as those ages 30 to 49 to do so.

- Thirteen percent of video viewers have uploaded a video file online for others to watch.

Young adults also trump older users in their experience with posting video content; 20 percent of viewers ages 18 to 29 have uploaded videos, compared with 12 percent of those 30 to 49 and roughly 5 percent of viewers age 50 and older who have posted video for others to watch.

- Ten percent of video viewers share links with others by posting them to a website or blog.

Madden wrote, "Some who feel compelled to share the video content they find online prefer to do so in a more public way." Again, younger users have a greater tendency to share what they find; although 22 percent of video viewers ages 18 to 29 post links to video online, just 7 percent of those ages 30 to 49 do so. Madden added, "The flurry of link sharing by younger users has helped to shape the most-viewed, and top-rated lists on popular video sharing sites. Many young adults and teenagers, who are avid users of social networking sites and blogs, post videos to their personal pages and profiles, which then get linked to or reposted by many other users."

In addition to asking who discovers, watches, and shares new videos, you should also ask, What categories or types of video do they watch?

Several organizations have conducted surveys to identify the most popular types of online video content, including Advertising.com, Burst Media, Frank N. Magid Associates, Ipsos Insight, the Online Publishers Association, the Pew Internet & American Life Project, Piper Jaffray, and TNS. As Figure 2.4 illustrates, eMarketer looked at all this data and estimated in February 2008 that news/current events was the most popular genre of video, followed closely by jokes/bloopers/funny clips (comedy).

According to the July 2007 Pew report that I cited earlier, 37 percent of Internet users have watched news videos, with 10 percent watching this genre of video on a typical day. In addition to the plethora of news content posted on video sharing sites like YouTube, Pew reported, "news-related video can now be found on virtually any website associated with major network TV news channels, cable TV news, and on most mainstream newspaper websites. Additionally, blogs, video podcasts, personal websites and social networking websites also feature news-related video."

Figure 2.4. Types of online video content that U.S. online video viewers watch monthly or more frequently (2007, % of viewers). (Source: eMarketer.)

Comedy and humorous videos are the second-most-viewed genre of online video among the total population of online adults; 31 percent of Internet users have watched or downloaded comedic or humorous videos and 7 percent do so on a typical day. For young adults, comedy is the most popular category. However, on a typical day, young adult Internet users are equally as likely to view news and comedy; 15 percent of those 18 to 29 report viewing in both categories on the average day. "Indeed, much of the content viewed by young adults, such as clips from The Daily Show or The Colbert Report blurs the line between news and comedy," reported Pew.

Music videos are another popular category. Like news, music videos can also readily cross over into the comedy category. Weird Al Yankovic's "White and Nerdy" music video is one of the most-viewed videos of all time on YouTube and is listed in both the music and comedy category. Overall, 22 percent of adult Internet users watch or download some type of music videos online and 4 percent do so on a typical day.

Videos with educational content are also popular. Overall, 22 percent of Internet users watch educational videos, and 3 percent do so on a typical day. Sometimes referred to as "how-to" or "DIY" videos, these clips range from those that provide practical everyday tips, such as "How to fold a tee-shirt perfectly," to those that visually illustrate theories or concepts, as is done in "Web 2.0...The Machine is Us/ing Us."

This brings us to the next question: When do opinion leaders discover new videos worth sharing with their followers?

According to the Pew report, 19 percent of viewers watch online video on a typical day. However, "Few are consistently finding content that's compelling enough to share on a daily basis—just 3% send video links to others every day—but roughly one in three online video viewers will share links at least as often as a few times per month."

Now, if the 3 percent of online video viewers who share links on a daily basis is "too small"—and the 33 percent who share links a few times per month is "too large"—then what percentage would be "just right" to answer the question, When do opinion leaders discover new videos worth sharing with their followers?

I'm just spitballing here, but I think opinion leaders are watching online video on a daily basis and discovering new videos worth sharing with others a few times per week.

As Rogers noted, "One role of the opinion leader in a social system is to help reduce uncertainty about an innovation for his or her followers. To fulfill this role, an opinion leader must demonstrate prudent judgment in decisions about adopting new ideas."

Pew also found that those watched video "yesterday" reported more social viewing when compared with those who did not watch online video on the day prior to the survey. In other words, watching new videos on a daily basis enables opinion leaders to prudently share a few of them with others on a weekly basis.

This behavior is consistent with the following observation by Rogers: "The interpersonal relationships between opinion leaders and their followers hang in a delicate balance. If an opinion leader becomes too innovative, or adopts a new idea too quickly, followers may begin to doubt his or her judgment."

This behavior is also consistent with the way people spread rumors. In the Boston Sunday Globe on October 12, 2008, Jesse Singal observed, "Aside from their use as a news grapevine, rumors serve a second purpose as well, researchers have found: People spread them to shore up their social networks, and boost their own importance within them."

Researchers have also found that "negative rumors dominate the grapevine" and that "people are rather specific about which rumors they share, and with whom."

So, does discovering and sharing a new video demonstrate more prudent judgment than discovering and sharing rumors? You be the judge.

For example, the #1 most viewed video of all time is "Avril Lavigne - Girlfriend" from RCA Records. It was added to YouTube on February 27, 2007, and had more than 118 million views as of April 2009.

Tune out the Avril Lavigne song and pay attention to the data below it:

The song had over 383,000 text comments, making it the #3 most discussed YouTube video of all time.

It had been favorited over 258,000 times, making it the #14 top favorited of all time.

It had over 315,000 ratings.

In addition, I used Yahoo! Site Explorer to discover that about 13,700 pages link to the pop music video's URL.

In other words, a lot of people on other YouTube channels, MyBlogLog communities, and Avril Lavigne fan sites shared a link to "Girlfriend" with their other friends. Does this demonstrate prudent judgment? If I were the target demographic, then I could render an impartial opinion.

This brings us to the next set of questions. One of them is, Where do opinion leaders watch new videos? Another is, Where do they go to watch them? And the third is, Where do opinion leaders share some of the new videos they've watched?

Why ask multiple questions? Because in addition to the two actions (finding and sharing videos), "where" can mean either a physical place or a virtual one.

We've already established that people don't watch new videos today the same way that people watched the final episode of M*A*S*H. That episode ("Goodbye, Farewell and Amen," February 28, 1983) was viewed by 106 million Americans—77 percent of the television viewers that evening—making it the most watched episode in U.S. television history, a record that still stands.

According to legend, "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" was watched by so many people that the sewage systems of several major cities were broken by the tremendous number of toilets being flushed simultaneously right after the end of the two-and-a-half-hour long episode. Now, even the YouTube video "Avril Lavigne - Girlfriend" hasn't had that kind of sudden impact.

Once again, the only market research I've seen that even begins to ask some of the right questions is the Pew report on Online Video by Mary Madden:

www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Online_Video_2007.pdf

According to the Pew report, 59 percent of online video consumers watch at home, and 24 percent report at-work viewing. In addition, 22 percent watch online video from a "third" place other than home or work.

Where is this "third" place? Well, for a road warrior, it could be a hotel room. For a homebody, it could be a library. For a college student, it could be a dorm room. And for any of these, it could be a coffee shop or mobile phone.

Nevertheless, these percentages are all too large to identify opinion leaders. However, when asked where they watched online video yesterday, 19 percent reported at home, only 6 percent reported at work, and just 3 percent reported a third place. Opinion leaders may be watching videos at home the day before and then watching at work a few times per week.

No matter where opinion leaders are when they watch new videos, you will also want to know where they go to watch them. Although this sounds like a line from the cult film The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension, it isn't. Buckaroo said, "No matter where you go, there you are." I'm asking, "Whether you are at work, at home, or someplace else, which online video site do you go to in order to watch new videos?"

For the answer, let's look as some recent market research by comScore Video Metrix. As Table 2.3 shows, more than 147 million U.S. Internet users watched an average of 101 videos per viewer in January 2009. This means Americans viewed more than 14.8 billion videos that month. As my mom, who was a math teacher, used to say, "That's more than you can shake a stick at."

Table 2.3. Top U.S. Online Properties Ranked by Videos Viewed, January 2009

Property | Videos (000) | Share (%) of Videos |

|---|---|---|

Total Internet : Total Audience | 14,831,607 | 100.0 |

Google Sites | 6,367,638 | 42.9 |

Fox Interactive Media | 551,991 | 3.7 |

Yahoo! Sites | 374,161 | 2.5 |

Viacom Digital | 287,615 | 1.9 |

Microsoft Sites | 267,475 | 1.8 |

| 250,473 | 1.7 |

Turner Network | 195,983 | 1.3 |

AOL LLC | 184,808 | 1.2 |

Disney Online | 141,152 | 1.0 |

| 102,857 | 0.7 |

[a] Total U.S. - Home/Work/University locations. Rankings based on video content sites; excludes video server networks. | ||

Now, comScore reported that Google Sites ranked as the top U.S. video property with 6.4 billion videos viewed—representing a 42.9 percent share of the online video market. But, as I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, YouTube accounted for more than 99 percent of all the videos viewed at Google Sites.

And at the bottom of the press release announcing this data, comScore reported that100.9 million viewers watched an average of 62.6 videos per viewer on YouTube—for a total of 6.3 billion videos that month. This gave YouTube a 42.6 percent share of the online video market.

The comScore press release also reported that 54.1 million viewers watched an average of 8.7 videos per viewer on MySpace—for a total of 473 million videos. This gave MySpace a 3.2 percent share of the online video market.

Here's the net net: If YouTube is #1 with more than a 42 percent share and MySpace is #2 with only 3 percent, then YouTube will make you or break you and the other online video sites can only have impact collectively, not individually.

Now let's ask, Where do opinion leaders share new videos? This brings us a surprising finding in the Pew report, "Online video consumers are just as likely to have shared a video viewing experience in person as they are to have shared video online. The picture of the lone Internet user, buried in his or her computer, does not ring true with most who view online video."

The Pew report found that 57 percent of online video viewers have watched with other people, such as friends or family. Young adults were the most social online video viewers; 73 percent of video consumers ages 18 to 29 have watched with others.

Once again, this is too large a percentage to identify opinion leaders. But there are ways to spot them through observation.

For example, Brian Stelter of the New York Times wrote an article on January 5, 2008, that observed, "In cubicles across the country, lunchtime has become the new prime time, as workers click aside their spreadsheets to watch videos on YouTube, news highlights on CNN.com or other Web offerings."

He added, "In some offices, workers coordinate their midday Web-watching schedules, the better to shout out punch lines to one another across rows of desks. Some people gravitate to sites where they can reliably find Webcasts of a certain length—say, a three-minute political wrap-up—to minimize both their mouse clicks and the sandwich crumbs that wind up in the keyboard."

So, go take a walk around your office at lunchtime. When you stumble across five people who are on some sort of site that is not work related, don't interrupt them. It's okay. It's lunchtime.

But observe the social motivation—the desire to share a viewing experience with someone else—which influences the way users experience online video. Then, watch closely to see if one member of the small group does the driving while others sit in the passenger seats. Could this opinion leader have discovered some of these new videos at home yesterday?

Now, if this were a map of the online video market, then this would be the spot where you'd read the warning, "Here be dragons!" In other words, we're about to enter dangerous or unexplored waters. Why? Because there is at least some market research that asks the question, Why do some new videos go viral? But, there is no market research I know about that even begins to ask the right question: Why don't more new videos go viral?

It seems that market researchers know that most of their paying clients want to hear about successes stories. But this can give you a skewed view of the online video market. This tendency to overestimate the success rate of online videos is called the Lake Wobegon Effect because it assumes that "all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average."

But, "In some cases, nothing succeeds like failure." That headline in the December 10, 2006, Boston Globe caught my eye. The headline appeared over an article by Robert Weisman about Gustave Manso, a Brazilian-born finance professor at MIT's Sloan School of Management.

Weisman wrote, "Manso thinks it's nearly impossible for companies to develop breakthrough products, processes, or approaches without encouraging the kind of trial and error that inevitably generates failures as well as successes. For him, the challenge is to craft incentives that will make creative people comfortable with thinking big and taking risks."

And he quoted Manso as saying, "To induce employees to explore new ideas, you have to tolerate early failure and reward long-term success."

Get it? Got it? Good.

So, let me share a story with you of an early failure in YouTube and video marketing that my long-time friend Michael Kolowich had the courage of integrity to share with readers of his Web Video Expert blog. It's the story of the Internet TV channel that Michael's firm, DigiNovations, created in January 2007 for the Mitt Romney for President campaign. Mitt TV is widely acknowledged to be the first comprehensive video channel for a presidential campaign.

However, on February 7, 2008, Romney suspended his campaign for the presidential nomination following the results of the 2008 Super Tuesday primaries—despite raising $110 million for his campaign ($45 million in personal loans and $65 million from individual donors). In other words, winning your party's nomination and getting elected president involves much more than just raising campaign contributions.

On February 10, 2008, Kolowich posted "Ten Lessons from Mitt TV." I encourage you to read the entire post on his Web Video Expert blog. But here's a sampling of lessons that you will want to know about and discuss with others:

- YouTube is a two-edged sword.

A lot of the 2008 presidential campaigns relied on YouTube channels generously "given" to them by the video site. And there's no question that a lot of independent traffic saw their clips based on YouTube searches. But if part of the idea was not just to inform but also to inspire people to act (give money, sign up, give us their email, etc.), then Kolowich thinks YouTube was weak at the "call to action" part. That was certainly true in 2007 and early 2008, although YouTube's "call to action" offerings got stronger in October 2008, when "click to buy" links were added to the watch pages of thousands of YouTube partner videos.

- A YouTube channel is necessary but not sufficient.

Because of #1, the Romney campaign decided to invest in its own very rich channel that eventually had more than 400 video clips on it, which were closely associated with their "calls to action" in the campaign. And, according to Kolowich, the most remarkable statistic of all is that more people watched the Romney campaign's clips on Mitt TV than on its YouTube channel. Other marketers have reported similar results.

- A content-managed video platform is vital to success.

Kolowich believed that a content-managed web video publishing system was vital to building something as sophisticated as Mitt TV. But he didn't realize at the time that the share of market of the video search engines that crawled this platform was getting smaller each and every month.

- Seeds and feeds build viewership.

Although the Romney campaign had its share of "I want my Mitt TV" people tuning in every day to see what was new, the key to building Mitt TV's audience (which got as high as 70,000+ viewings a day in the late stages of the campaign) was outreach—to bloggers, through press releases, through RSS feeds. The result was that there were more than 23,000 references to Mitt TV on Google and more than 2,800 sites linking to Mitt TV. However, the vast majority of videos that appeared in Google universal search results from May 2007 through November 2008 came from YouTube, not video search engines or individual websites.

- Don't believe everything you read about clip length.

The conventional wisdom is that video clips need to be under 2 minutes to have a prayer of getting watched. But looking over the viewing statistics, Kolowich saw that many of the most popular clips were complete speeches or events that were as long as 20 minutes or even more. It's also worth noting that the duration of the average online video viewed at Megavideo was 24.9 minutes in January 2009, according to comScore Media Metrix.

- Listen to the data.

According to Kolowich, one of the advantages of having their own Internet TV channel was that they could get a tremendous amount of data about what worked and what didn't. Since YouTube Insight wasn't available until March 2008, Kolowich could watch patterns of viewership and correlate it to different outreach efforts in 2007. He could see which clips were being viewed and for how long. And he could see where traffic was coming from. All this was useful in making Mitt TV a more effective channel.

So, why didn't more of Romney's new videos go viral?

For starters, Kolowich says the goal of Mitt TV wasn't to go viral. As he said, the objective was "to inspire people to act (give money, sign up, give us their email, etc.)." And Mitt TV reached this goal.

As Kolowich revealed in a post on April 23, 2008: "Without disclosing specific numbers, we found that when we could use web video to bring a viewer to the campaign website and call them to action, the payoff—in terms of contributions, volunteer sign-ups, referrals, event attendance, etc.—was orders of magnitude more than the cost of serving up the video. That's why we favored video on our own website over the many clips we posted on YouTube."

But the other reasons why so few of Romney's new videos went viral can be found in the previous paragraph: the campaign treated online video like it was just a new type of infomercial and it favored video on its own website over the clips it posted on YouTube.

Was this the right video marketing strategy? Would the Romney campaign have done any better if its goal had been to change people's presidential preference instead of prompting them to give money, sign up, and provide their email? Would the Romney campaign have done any better if it had favored YouTube over Mitt TV?

I still don't have all the answers, but I'm beginning to ask the right questions: If online video is better at informing, inspiring, and connecting than it is at direct response, then in addition to preaching to the choir on Mitt TV, shouldn't the Romney campaign have also spent more time reaching out bring more people into the church? Should the Romney campaign have spent more effort reaching out to opinion leaders and trying to win the "invisible caucus" that was held on YouTube in 2007?

What's an invisible caucus? As Linda Feldmann of the Christian Science Monitor reported on February 26, 2007, there was a lot of media buzz about "what's come to be known as the 'invisible primary'—the early jockeying for money, top campaign staff, and high-profile endorsements that winnow the presidential field long before any caucuses or primaries are held."

On June 15, 2008, the Pew Internet Project reported 35 percent of Americans have watched online political videos—a figure that nearly triples the reading Pew got in the 2004 presidential race. And Pew also found that supporters of Barack Obama outpaced supporters of both Hillary Clinton and John McCain in their usage of online video.

So, I'm calling the early jockeying for opinion leaders in YouTube's news and politics category an "invisible caucus." And it is worth asking, Did winning it help a former community organizer's presidential campaign "take off" while skipping it hurt a former CEO's chances of getting a critical mass of opinion leaders to share his videos with others?

Who knows? Nevertheless, on April 23, 2008, Kolowich posted this to his blog:

Both the Romney and Obama campaigns understood the power of video not only to get the message out but also to attract, engage, and actuate supporters on the main campaign website.... It may be pure coincidence that the candidates' fundraising performance correlates with their sophistication on Internet video, but our experience suggests that sophisticated use of web video certainly has an impact on keeping an active, vibrant base of supporters who visit often and want to stay involved.

That leaves just one more question to ask: How does marketing with video work? This is the question that 9 of the 10 remaining chapters in this book will tackle. (In the final chapter, we'll revisit the five Ws and an H.)

To help set the agenda for the next 90 percent of this step-by-step guide, let me share the highlights of Suzie Reider's presentation at The Edge, a creative event thrown on September 19, 2008, by the Boston AdClub. Her presentation was entitled "Marketing with Video."

Reider told the luncheon crowd about the lessons she had learned from her time with one of the world's largest social media communities. And from her point of view, YouTube is the combination of "both media and community."

As Figure 2.5 illustrates, Reider said there are six concepts to keep in mind when marketing with video:

- Create ads that work as content

She showed "Amazing Ball girl catch," a Gatorade commercial directed by Baker Smith of Harvest Films, that was posted in June 2008 and had almost 2 million views in April 2009.

- It's all about the dialogue/conversation

She showed "Tiger Woods 09 - Walk on Water." After Levinator25 posted a video of "the Jesus shot," a glitch in Tiger Woods PGA TOUR 08, the folks at EA SPORTS uploaded a funny response on August 19, 2008, that had over 3 million views as of April 2009.

- Ideas come from everywhere

She showed "Battle at Kruger," the most viewed "pets and animals" video of all time, with 42.8 million views in April 2009. The viral hit has become the subject of a National Geographic Channel documentary.

- Connect the dots

She showed the Heinz "Top This TV" Challenge, a YouTube contest that generated nearly 4,000 qualified contest entries, 105,000 hours of interaction with the brand, and an increase in ketchup sales.

- Have thick skin... Feedback is public

She showed "Dove Evolution," the Ogilvy spot created by Tim Piper, which had over 8.7 million views as of April 2009 and inspired the "Slob Evolution" spoof, which had almost 1.3 million views as of that date.

- Metrics matter

She showed YouTube Insight, a free tool that enables anyone with a YouTube account to view detailed statistics about the videos that they upload to the site.

Reider closed her presentation with a surprising example of who is marketing with video: The Royal Channel, the official channel of the British monarchy.

The royal household launched its channel on YouTube in December 2007 and had 80 videos in April 2009. The channel showcases both archive and modern video of the queen and other members of the royal family and royal events. The most viewed video was "The Christmas Broadcast, 1957," or "Queen's Speech." The access to this restricted footage was granted to mark the 50th anniversary of the first televised Christmas Broadcast. As of April 2009, it had more than 1 million views, over 3,500 ratings and had been favorited more than 1,500 times.

Now, if the British monarchy has been marketing with video for more than a year and a half, then it's time for even the most traditional organization to get started.

And like the kids in the New Yorker cartoon by Lee Lorenz back in Figure 2.1, we still don't have all the answers, but we are beginning to ask the right questions:

Who discovers, watches, and shares new videos?

What categories or types of video do they watch?

When do they discover new videos?

Where do they share new videos?

Why don't more new videos go viral?

How does marketing with video work?

And that's a great way to get started.