Chapter 2. Storytelling and Directing

Michael W. Dean

I know a lot about filmmaking on an indie, short-form, YouTube level and even a lot about more complicated, long-form, pro filmmaking that approaches a Hollywood level. You don’t need to know all that I know to make great YouTube videos, because all of it would fill many books. (In fact, I’ve written, edited, or contributed to several books.)

| www.cubbymovie.com (URL 2.1) |

I’m going to take the more basic and YouTube-specific of that info and distill it down into the two chapters of information you’ll really need to be a contender on YouTube. A lot will be covered quickly, but not in a way that misses anything you need to know to make videos that look and sound better than most of the fare on YouTube.

The basics of writing, lighting, sound, camera placement, and editing are the same, whether you’re shooting with a webcam in your bedroom, making a $100,000,000 Hollywood blockbuster with a huge crew and movie stars, or shooting scrappy little documentaries that change the world with good mini-DV cameras, with a small volunteer crew mostly made up of film school students, and with a professional editor, like I did with my two feature films.

The Importance of Storytelling

Most people when they get a video camera just start shooting. I know I did. But you really should do some exploration into storytelling so you have something worthwhile to shoot.

The Basics

I cannot overstress the importance of storytelling. Storytelling at its most basic is just one person talking to another person. It predates spoken language, probably originating with the Neanderthals 500,000 years ago, grunting and emoting with their hands around a fire in a cave to describe the day’s hunt.

Today, storytelling at its most basic is two people sitting on a couch talking—see Figure 2-1—not much different from the cave stuff when you really think about it.

On YouTube, as with any motion art, the “story” is the video. Your goal on YouTube is to have you sitting on the “virtual couch” of the Internet telling your story, whether it’s a story from your life or one from your imagination. The story is what grabs people.

Sure, if you’re young and cute and female, people will probably be more likely to pay attention to you for a minute on YouTube. But that’s not the story. And it’s not really positive attention, and it isn’t something that lasts. And it’s not going to make you a lot of money. Storytelling is what grabs attention, keeps attention, and makes money (again, if that is your goal). Alan is making money on YouTube, but he didn’t set out with profit as his goal. He set out to make good art and share it with lots of people. I don’t make money on YouTube; I only want to spread art and am satisfied with that. We’re speaking to both camps here. We’re making the assumption that you want to make good videos and have people pay attention to them. Storytelling is the most important thing. People remember a lot of things about any piece of motion art (the term I’m going to use for anything from webcam YouTube videos to Hollywood blockbusters). People remember the stars; they remember the great lines of dialogue, the look and feel, the music, and more. But the main thing they remember is the story. Think about movies you love. You love them because the story spoke to something inside you in some important way. Think about YouTube videos you love. They have a great story, even if the film is only 30 seconds long. The story is what happens in a piece of motion art. It’s the thing that speaks to some common thread of the human condition.

Note

The best way to learn a new skill is to read up, ask questions, do real-life experiments, take notes, review your notes, and then try some more experiments. If this sounds like school to you, it’s not. School tells you what to learn and when to learn it. This is combining action with thought and experience and doing it at your own pace. It’s learning what you need to learn and ignoring the rest. School would never put up with this. This is the most important thing I’ll contribute in this book, and this piece of advice is worth the price of the book by itself. And it comes from a guy who got in trouble for skipping school to go to the library to actually learn things. I’m now in demand in a bunch of cool worlds, and most of the kids I went to school with have nowhere jobs. A guy who used to beat me up writes for the local paper, which is cool, but the last thing I read by him was a story about how evil rock music is and why Nirvana should be banned and all their records burned. Steve Albini, who engineered the Nirvana record In Utero, also uses this “self-teaching with study, experiments, and notes” idea. Check out my video interview with him where he talks about it:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mw62MYwe5pQ (URL 2.2)

I’ve often said that a well-told story interests me even if I have no interest in the subject matter, because it speaks to something common in all people. Of all the documentaries I’ve ever seen, one that really stood out, Spellbound, was one about spelling bees, even though I have no interest in spelling bees. One of my favorite popcorn movies (big Hollywood movies that don’t change your life but are fun to kill two hours and eat some popcorn) is Happy Gilmore, even though I hate golf.

Storytelling is different from writing, though they are related. You can tell a story without even using any words, and words are what writing produces. Some of the most compelling pieces of motion art (especially commercials) have little or no dialogue. But something always happens in motion art. Your first job as a video creator is to make things happen on the screen. This can be done by writing or otherwise visualizing a plan and then enacting that plan and filming and editing the result, or it can happen by filming things that happen without your intervention and presenting them in a compelling way with your editing. Both methods are types of storytelling.

Conflict Is the Essence of Drama

The first thing they teach you in “real” film school is that “Conflict is the essence of drama.” It’s true. Without conflict, movies and TV would fall out of the screen and drip lifelessly onto the floor, as this photo of my cat, Charlie (Figure 2-2), looks about to do. (The white blur is actually a second cat leaping by, but Charlie didn’t catch it. She’s too catatonic.)

All movies and all TV shows incorporate story, with characters clashing with one another (see Figure 2-3), having various types of crises of conscience, and then resolving the conflict, tying it all up in a nice neat package near the end of the show. These types of crises of conscience might be called confrontation—in act one, the characters are introduced, the problem is defined, the story set up; in act two, it evolves, it gets worse, the conflict grows; and finally in act three, it gets resolved somehow. The same is true of most books, plays, and even songs, especially hip-hop and country music, the two most story-driven music genres in existence. The fans of the two genres may not get along, but they have more in common than any other genres (except country music probably has more guns and drugs and booze and sex).

This method of conflict/drama/resolution is called the three-act format. A common way this is expressed in Hollywood films is what is known as the hero’s journey. Almost all Hollywood movies follow this journey—to the point that it becomes cliché. To the point that, if it’s not there, the audience feels cheated, even if they can’t describe what’s missing. To the point that, if certain types of events don’t happen at almost exactly 10 minutes, 18 minutes, 29 minutes, 46 minutes, 101 minutes…, people feel uneasy when they leave the theater. (My wife and I once had a very long discussion about whether this is because people are used to seeing it or because people need it because there’s something inherent in the human experience that makes people want to organize stories into this format. The conclusion we’ve both come to is “It’s a bit of both.”)

Most hero’s journeys are in three-act format, and in movies, most three-act formats contain the hero’s journey, but they do exist independently of each other.

When a hero’s journey is not in three-act format, it’s usually a cyclical story, with parallel stories that occasionally intersect and the beginning of the film being part of the same scene that ends the film. A good example of this is Pulp Fiction, which still contains a hero’s journey, where there is a battle in the innermost chamber and enemies become friends.

The evil baby, Stewie, on Family Guy (one of the only TV shows I’ll watch…most TV sucks) summed up three-act format perfectly, while sarcastically deriding Brian the dog for not working on his novel:

“How you, uh, how you comin’ on that novel you’re working on? Huh? Gotta a big, uh, big stack of papers there? Gotta, gotta nice little story you’re working on there? Your big novel you’ve been working on for three years? Huh? Gotta, gotta compelling protagonist? Yeah? Got a’ obstacle for him to overcome? Huh? Got a story brewing there? Working on, working on that for quite some time? Huh? Yea, talking about that three years ago. Been working on that the whole time? Nice little narrative? Beginning, middle, and end? Some friends become enemies; some enemies become friends? At the end, your main character is richer from the experience? Yeah? Yeah?”

So, yeah, the three-act format is a cliché but one worth understanding. And by the way, once I explain it to you, you’ll never look at Hollywood movies quite the same way. You’ll feel like you’re being lied to. Because you are. Life is not that neat, things are not always completely resolved, and every situation does not have a lesson or a silver lining. Many do, though. I have a pretty positive outlook on life, but I hate sugar coating. In any case, here you go…

The Hero’s Journey

A hero’s journey story has three acts. Three distinct feelings. The first act is 30 minutes, the second act is 60 minutes, and the final act is 30 minutes. If the movie is longer or shorter than two hours, adjust accordingly. But regardless, the second act is about twice the length of each of the other two. This is shown in Figure 2-4.

The first act takes place in the "normal world,” the world the protagonist (hero) normally lives in. During this first act, we meet the hero, find out his (or her) problem, and see his call to action. This is him being called to act heroically, in a way that would lead to the rest of the story. The hero always refuses the call the first time. Then something changes, it becomes personal, and he has no choice but to answer the call to greatness and risk it all to become a hero. The hero is usually played by Brad Pitt, Bruce Willis, or Wesley Snipes.

The hero meets a mentor, an older person who used to be at the top of the same game the hero wants to operate in, but the mentor is now retired or crippled in some way, so all he has to pass on is knowledge and wisdom. He also usually passes on some sort of talisman—an actual physical object—to the hero. The talisman seems useless at this point but will help the hero in some way in the third act. The mentor is usually played by a handsome, older black guy with a deep voice, and it’s usually Morgan Freeman.

The mentor helps the hero assemble a ragtag crew of misfits as his team to help him in his hero’s journey quest. There’s always one guy on the team who seems like he’s going to get everyone killed. This is the guy who makes you think, “Why is that guy on the team? He’s going to get everyone killed!” This character is always played by a short, squirrelly, funny-looking white guy, often Steve Buscemi.

Once the hero’s team has completed its training, the assembled team will always walk in semi-slow motion side by side toward the camera, wearing whatever outfits they will wear in their new world. This shows that they’re now a single unit, not four or five individuals. This badass walk is how you know act one has ended and act two is beginning.

If it’s a movie about hookers, they’re dressed in pumps and miniskirts. If it’s about astronauts, they’re wearing space suits. If it’s Reservoir Dogs, they’re wearing cheap suits and skinny ties.

The second act takes place in the "special world,” the world of wonder where most of the story actually happens. This can actually be a different physical location from the normal world, or it can take place in some marginal society that’s still geographically in the same town as the normal world. But it’s often a different physical location. And when it is, part of the “journey” will involve the hero and his team traveling to that physical location.

In this special world, the hero will battle many foes and almost die several times (figuratively or literally). He will become stronger, physically and spiritually, with each battle, until he meets the ultimate evil (antagonist) in the third act in the battle in the innermost chamber. This is the climax of the film, and it usually happens in the middle of act three. The most quotable lines from the movie come from this part. The quote on the movie poster often comes from this part.

If it’s a cowboy movie, the battle in the innermost chamber takes place in the corral as a shootout with the villain. If it’s a courtroom drama, it is closing arguments screamed by lawyers and defendants in front of a jury while the judge bangs his gavel and demands order. If it’s that dodgeball movie, the battle is the dodgeball championships in Las Vegas. During the battle in the innermost chamber, the hero will die (figuratively or literally), resurrect with wounds (this is probably a Jesus metaphor), and stand again to finally slay the beast, even though he’s bleeding (figuratively or literally).

Then there’s the denouement (pronounced “day nu ma”), the gentle anticlimax where the hero gets the girl, gets the gold, saves the farm, and returns to the normal world. But now he’s richer for the experience, changed for the better, and bearing gifts (literal or symbolic) to help his community. (This section often leaves one or two seemingly small questions unanswered, which sets the story up for a sequel, just in case the film makes a lot of money.) Roll credits.

Do you feel cheated? You should. Hollywood relies on this formula to make safe movies that are guaranteed to turn a profit. They even wrap this formula around true events that do not occur in three acts, in biopics and documentaries. Sometimes, especially in reality TV, the conflict is even manufactured, put together behind the scenes by the producers. (See Figure 2-5.)

No cats were harmed or even mildly irritated in the making of these images. They illustrate the idea of contrived conflict, and it does look like the producer is strategizing behind the scenes to create conflict. It looks like Debra Jean is putting one cat near the other cat, but she’s actually gently removing the cat who was about to fight, thereby stopping a fight.

Scripts that don’t follow the hero’s journey recipe to a T are routinely turned down by producers, even if the story and writing are great. Hollywood has so much potential, and it’s almost always wasted. It’s sad. The hero’s journey does, however, have some good attributes. Study this formula, know it when you see it, and then rewrite the rules. Pick the parts you like, discard the rest, and make something brilliant. (Or do what South Park does and follow the formula to the letter, exaggerate all the bullet points, and make fun of it while you’re doing it.)

Most good videos have a discernable beginning, middle, and end; even unscripted vlogs (video blogs—confessional, one-person-looking-into-the-camera-and-baring-his-soul-type videos, which are very popular on YouTube) have these three parts. The best vlogs have a feel of introducing an issue, talking about the issue, and resolving the issue, and the best vloggers do this without even thinking about it.

A Likable Main Character

Every story, no matter how short or unconventional, needs at least one likable main character. This character doesn’t have to be perfect—he can actually be quite flawed—but there has to be someone for the viewer to “root for” and live vicariously through.

I figured this out recently. My first novel, Starving in the Company of Beautiful Women, did not have a likable main character. In fact, the main character dies on page 1, and then the book is all back story. While it’s hard to cheer for a guy who’s already dead on page 1, this might have worked if I’d made him a little more likable. The cult film Liquid Sky has no likable characters.

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwOHKKJxrgA&feature=related (URL 2.3) |

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9-n9gpFVpk&feature=related (URL 2.4) |

It’s a very interesting movie otherwise, especially visually and sonically, and probably would have had a wider audience if there had been someone to root for. But the characters don’t even care about themselves, so why should we care about them?

The need to have a likable character is even seen in nonfiction coverage of stories with characters you can only despise. In every news show that covers the brutal murder of a family in a home invasion, they always interview the crying surviving relative. That’s the person you root for in that story; they’re likable because you feel sad for them.

Brevity Is the Soul of Wit (or 2 Minutes to Fame)

Basically, as a filmmaker, you have about 2 minutes to get the attention of your viewers. Maybe less. Here I’ll tell you why.

Hit ‘Em Over the Head and Get Out

YouTube currently allows you only 10 minutes to tell each story anyway. It’s pretty hard to make a fully rendered hero’s journey story in 10 minutes. It can be done, but you’ll be pushing it and skipping over the development of character and plot that requires 90 minutes or more to really do well. I recommend going with two-act format, which works really well on YouTube, especially for videos less than 5 minutes. (And most videos that go viral are less than 5 minutes, because people have really short attention spans these days.) With a short-form two-act format, you’re basically hitting ‘em over the head, then getting out quickly.

Note

Alan spends more time on YouTube than anyone I know, so I believe it when he says, “The average length of a viral video is 2 minutes.”

The two-act format is basically a setup and a knockdown. A “Knock knock” and a “Who’s there?” A joke and the punch line. As you see in Figure 2-6, this often works out to 90 seconds of setup and 30 seconds (or less) of punch line.

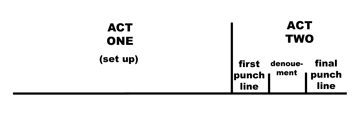

Another way to do it is 90 seconds of setup, 15 seconds of punch line, 10 seconds of denouement, and then another quick punch line after you feel resolved and relaxed. (See Figure 2-7.)

Even if your video is not humorous, a two-act setup and knockdown works great on YouTube, on the small screen, with tight time limits.

Think about the audience of YouTube. It’s mostly the post-MTV generation—folks who want action, change, fast pacing, and a quick bang for their (free) buck. It is not usually the same people who watch long, slow, black-and-white art films with subtitles. And even though some people like that (like me) are viewers and even content creators on YouTube, when we’re on YouTube, we don’t really have that mind-set. For many people, the Web in general, Web 2.0 (social networking like YouTube, MySpace, and Facebook) in specific, and YouTube even more specifically are used as brief time killers between other tasks. People know that they can go to YouTube, click a bit, and be made to laugh, cry, and laugh again in less than 5 minutes. From watching three complete videos. That’s more or less the mind-set you’re playing to on YouTube.

Think about TV commercials. YouTube videos, at their best, are written with a pacing similar to that of TV commercials. TV commercials have 30 to 60 seconds to do it all. In this amount of time, a commercial has to grab your attention, introduce a product or service, make you understand the product or service, and make you care enough to part with your hard-earned money. They have to mention the name of the product or service three more times so you’ll remember it and then tell you where to go to get it. That’s a lot to accomplish in half a minute. I hate TV more and more, but more and more, the thing I still find watchable on TV is the commercials. That’s because the most creative minds graduating from film and art schools usually get bought up by ad agencies, because there is so damn much money to be made in advertising.

Note

I recommend that if you really want to understand advertising, and the world, you should watch the 1988 John Carpenter film They Live:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/They_Live (URL 2.5)

This 1988 low-budget dark comedy has a sci-fi motif, but it has more truth than most documentaries. They Live shows the world as it really is behind the matrix and has a lot of great stuff to say about advertising. You can get a copy of They Live used on Amazon for seven bucks plus shipping:

www.amazon.com/They-Live-Roddy-Piper/dp/B0000AOX0F (URL 2.6)

In general, I hate the idea of ads on TV, in magazines, on social networking sites (particularly MySpace, which is starting to look like TV—or more like four TVs going at once), or anywhere. I don’t buy things based on ads, and I consider ads obtrusive. When I want to buy something, I shop bargains, ask friends, and check user reviews. Check out these TV ads for milk, featuring an imaginary milk-fueled rocker named White Gold. These are some of the coolest bits of motion art ever created (and they’re ads for milk, a product I enjoy and actually consume a lot of). This is the story of how White Gold came to be: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fVXHRC0DG70 (URL 2.7)

This is the best one, his song “One-Gallon Axe.” It even has a llama and a Viking helmet! www.youtube.com/watch?v=nj1-ZZRajDU (URL 2.8) The guy is the singer in a real band in L.A. called The Ringers. They’re great:

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=GF_k-YYCpno (URL 2.9) |

The style and pacing behind advertising is a great way to get things done, get people’s attention, and make them remember something. Study commercials to learn how they work and then learn to subvert the tricks of advertising to serve your own agenda.

Slower Brevity and Wit

This “rule” of “Get it done fast, make your point, entertain, get out fast” is not hard and fast. Many vlogs work well with a slower, more laid-back pace, and they still captivate your attention. This vlog by Alan called 50 Things (see Figure 2-8) is slower yet still very compelling: www.youtube.com/watch?v=LjfL5WL4ZBQ (URL 2.10)

This video manages to work well in a relatively short time frame, because the subjects covered are interesting, seamlessly going between intimate and funny, and Alan has a good, very natural, delivery. He’s confident without being cocky. The mood is interesting, the feeling is from the heart, and it is both uplifting and personal.

A cocky mood for delivery can work also in vlogs and other types of “personal” videos. I don’t personally like this style as much, but a lot of people seem to dig it. Here’s a good example from user DoggBisket:

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_wCbwIwfQg (URL 2.11) |

This is also a good example of an effective collab video, involving several people in addition to DoggBisket, including Alan. It also credits everyone well in the credit roll at the end. This is going above and beyond; most people just credit in the More Info link on the top right of the page. Crediting in the video itself is a nice touch for the people who work so hard for free to help out.

Keep in mind that the basic mood, and the audience, of YouTube is highly influenced by television commercials, rock videos (which are basically commercials for music), and even talk radio, as you can see in the video by DoggBisket. If something takes 8 minutes to say but could be said in 4 minutes, 4 minutes is probably better. Johnny Cash said that if a line of lyrics doesn’t advance the story in a country song, cut that line. An old punk-rock nugget of wisdom from back in the day was “Why have a guitar solo when you can just make the song shorter?” and, with the occasional exception, I tend to agree.

You don’t need to chop your videos down to 60 seconds, but if you keep in mind the short attention span of the average YouTube viewer while writing and editing and go for punch rather than long, sweeping explorations, you’ll have a better chance of achieving the coveted “going viral” goal.

I recommend you start with some 5- or 8-minute projects and then work on shaving future ones down to 2 minutes for your better ideas after you get really good at writing, shooting, directing, editing, and promoting. Remember: 2 minutes to fame.

The Importance of Writing

You will need to write some for your story before you make a video. This can be as elaborate as writing a word-for-word script, writing a short outline, or even just writing it in your head, but the better videos all have some planning behind them.

Treatments and Scripts

Writing is related to, and part of, storytelling (and vice versa), but it’s so different that I decided to give it its own heading, one that’s equal to storytelling.

Note

See what I just did there? I pointed out that I am writing this. That’s called breaking the fourth wall in filmmaking; it’s when an actor stops acting and addresses the camera directly, in a way that “admits” there’s a camera. It can be an effective tool, when used sparingly, and for a planned mood, in drama and comedy, and is pretty much the basis of all vlogging by definition. Breaking the fourth wall is your first lesson on writing for motion art. Enjoy.

Storytelling is the broad strokes. When a Hollywood writer pitches a story to a studio, they often have only the brief outline of a story. There’s even something called an elevator pitch, which is supposed to be the shortest amount of time it takes to convey a complete story, like if you found yourself sharing an elevator with a producer for a ride of only a few floors. This is also called 25 words or less. The plot of most Hollywood films can be completely expressed in 25 words or less. For YouTube, think 15 words or less. This is true of most Hollywood films. Complicated ones that break the hero’s journey mold (and these are usually my favorite films) like Fight Club and Memento, still have some sort of three-act structure, albeit convoluted.

Once a Hollywood movie is sold, based on the pitch, and the writer is hired, they’re often asked to produce a treatment. This is a longer pitch (5 to 20 typed pages), but not quite as long as a full movie script (about 105 to 120 pages, which works out to about a minute per page in the final product). The treatment explains all the main characters, their ages, their names, a little background, their motivations, their dreams, their desires, their strengths, and their flaws. Then it has rough thumbnail breakdowns of the major plot points in the story. The full script is written using the treatment as a guide, after the treatment is approved (and usually meddled with) by the studio. Since YouTube gives you a maximum time length of 10 minutes, your treatments will not be nearly this long, if you even write treatments at all.

Note

Director accounts registered before January 2007 have no time limit, only the 100 MB basic file size limit that everyone has, or up to 1 GB if you use the Multi-Video Upload feature. Currently, all new accounts have a 10-minute limit to deter TV show and movie uploads.

Many YouTube viral videos do not have any kind of scripted, or written, aspects—they’re things like major news events, people hurting themselves in sports accidents, or a kitten doing something incredibly cute. But while these videos may get a million views, they don’t get many subscribers, because they’re so one-off. Here’s a 50-minute video on the history of YouTube that explains how the site grew: www.youtube.com/watch?v=nssfmTo7SZg (URL 2.12) Assuming you bought this book to build a following, you probably want to go for some form of scripted motion art.

How to Write an Outline

Alan does a lot of collab videos. (Collabs are collaborations—videos done with other people, usually over the Internet. More on this in Chapter 8.) One person Alan has done a lot of collabing with is Lisa Nova (username LisaNova). Lisa’s user page is here:

| http://youtube.com/user/LisaNova?ob=1 (URL 2.13) |

Lisa is one of the bigger rock stars of YouTube. Not only is she in the top 10 all-time most subscribed directors on YouTube, her work on YouTube led her to being a regular on MADtv for a season. She’s now getting so much work outside YouTube that she’s actually hired Alan. This is pretty sweet, and it’s one of the side benefits of doing amazing stuff on YouTube and making it great, even when it’s only a little fun parody video. That can grow into more. A lot more. One of the collabs Alan and Lisa did early on was this parody of an iPhone ad (see Figure 2-9): www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpUItDR5im4 (URL 2.14)

Alan wrote the concept and the copy and emailed it to Lisa. (Copy here means the words that the actor reads. Ad copy is the words actors in a commercial read.) Danny, Lisa’s producer and partner in art, shot a few takes of Lisa delivering the copy and sent the footage to Alan who had my wife, Debra Jean Dean, www.debrajeandean.com/ (URL 2.15) do the little “in time for Christmas” voice-over at the end. I engineered it and emailed the audio file to Alan. A script can be as easy as a single email.

Alan’s script consisted of one email, which covered everything. In that one communication, Alan asked Lisa and Danny to participate, outlined the concept, showed the copy, and even included a minimal bit of direction and a salutation and mention of a related project (“the Stickam idea”—doing “making-of” videos of this shoot through the live video site Stickam.com).When you’re working with talented people, that can be enough. Here’s what Alan sent Lisa, care of Danny.

Alan did “remote directing” via live video site Stickam.com and used a webcam to actually give Lisa direction as she shot her part, 2,000 miles away. It worked out well. If you want to see behind-the-scenes, it’s here:

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=d76vEPhDX7E. (URL 2.16) |

Choosing and Directing Actors

Actors are the talking puppets who bring your stories to life. OK, they’re more than talking puppets; they’re humans, with real emotions and feelings. Either these emotions and feelings can get in the way of putting your story on the screen or you can work with these emotions and feelings…and desires. That’s what a director does—“directs” the actors to channel their human experience onto the screen.

Choosing Actors

Most YouTube videos star amateurs as the actors. In fact, most YouTube videos star you and your friends. (That’s why it’s called YouTube, not ThemTube. ThemTube is our nickname for television.)

For vlogs, and for funny, cute stuff, having you and your friends is fine (Figure 2-10) and it sure beats ThemTube (Figure 2-11). But what if you have a more sweeping vision in mind? What if you want to make something “as good as Hollywood,” but better? You will need some people who can act.

For all the things that Hollywood does wrong, it does a lot right. What they do wrong is this: They tell the same hackneyed hero’s journey, happy ending story over and over. The situations may change, but it’s pretty much mostly all the same movie. This is called pandering to the lowest common denominator, and if you’re smart, you should probably be insulted by it.

What Hollywood does right is this: Everything is technically perfect. The sound is amazing, the cinematography is stunning, the editing is great, and the actors are really, really good. Sure, they may feature actors who are cute women more than actors with a lot of experience and talent, but even the cute women hired mostly for their looks can act.

When I say “They can act,” there’s something you need to understand, and that is “what acting is.” Acting is lying, in a creative way. Acting is convincing the camera, and the audience on the other end of the camera, that you are someone you’re not. It sounds a little sinister when put in those terms, but it’s really not. It’s an age-old art that predates YouTube, predates movies, and even predates the Greek plays of 400 B.C. It probably goes back to the first-ever caveman sitting around the campfire doing impressions of the second-ever caveman for the amusement of the third-ever caveman. We’ll never know, because there was no way to record anything then (that’s why that era is called prehistoric—before history), but I’d say that’s a safe bet.

Not everyone can act. Some hopefuls spend years and thousands of dollars on lessons, seminars, and books, and they still suck. Other folks are a natural and shine the first time a camera is pointed at them. The best actors are usually both. They’ve been doing skits and making people smile and believe since they were little kids, and they also have some formal training.

An important skill as a director, even on the tiny screen of YouTube, is to be able to recognize great acting. Another large part of what a director needs is people skills, and that includes the skill of being able to say “no” to someone, even if they’re your friend.

I don’t mean to sound like a hard ass. And your first few videos will probably star everyone around you—yourself, your family, your girlfriend or boyfriend, your neighbors, and even your cat. But as you get a lot better at writing, directing, filming, and editing, you’re going to want to find better actors. You’re telling stories, and you want people to believe the stories and be lost in the stories, so you don’t want bad acting to get in the way, any more than you want bad audio to get in the way.

A great way to make yourself a better director is to know good acting when you see it. And a great place to start is to know bad acting when you see it. Then, motivate your actors to do the opposite.

Here’s a clip titled Bad acting 101 on YouTube, and it certainly is:

| www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBcpW-7awMA (URL 2.17) |

The thing that I would say defines bad acting is “not being believable.” And the worst problem most people have with not being believable is "overacting.” That is, acting too big. Being too enthusiastic. Being too loud. Moving your arms and head too much. Bad actors often act like they’re on a stage in a play and need to exaggerate everything for people 100 feet away in the back of the room. Good actors realize they’re acting for a camera a few feet or even a few inches away, and they bring it down. Smaller and realer. Great actors are amazing to watch. They reach through the camera and touch your soul. They become the person they’re playing.

Note

It’s scary when someone is mad and they get louder and louder and yell a lot. But it’s even scarier when the madder they get, the quieter they get. It’s reptilian. Suggest this when directing actors, or try it yourself when directing yourself as an actor.

Here’s some good acting (as well as great cinematography and great directing). It’s a film by my friend Noah Harald who taught me how to make films, back in 1998.

| www.vuze.com/details/VGM52SKAUPNE4YU56XNHLWC6E4A2PFAO.html (URL 2.18) |

Note

Noah actually makes a living making films. Here are his resumés:

www.noahharald.com (URL 2.19)

His stuff is amazing. When he was on YouTube, he didn’t get many views, which illustrates something I find lacking in YouTube…. Diet Coke mixed with Mentos erupting gets upwards of a million views:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKoB0MHVBvM (URL 2.20)

Noah was nominated for an MTV award, he was on MTV at the awards show, and MTV showed his short on there, among a lot of other stuff. He is a graduate of Los Angeles Film School and has a paid webisode deal with Filmaka.com:

www.filmaka.com/filmaka_series.php (URL 2.21)

Here’s some good acting, on a video that’s gotten a lot of hits on YouTube:

| http://youtube.com/watch?v=CeAtbrYVqqs (URL 2.22) |

Sometimes, especially on the short-attention-span medium of YouTube, bad acting can work, if the people are actually good actors and are “playing” bad actors. Here are examples of bad (in my opinion) acting, where they’re not ashamed of it, where the bad acting “works”:

| Daxflame: http://youtube.com/watch?v=yUwVqL1xtVs (URL 2.23) |

| thebdonski: http://youtube.com/watch?v=MrZPxMoB92E (URL 2.24) |

(thebdonski is LisaNova’s brother, who is actually a fabulous actor who’s appeared in a few feature films but plays it down here…or plays it up, depending on how you look at it.)

Directing Actors

Directing can include everything that leads up to what you see on the screen. In Hollywood, some directors mainly concern themselves with directing the actors. Others are more into directing the cameraman and just let the great actors do most of it themselves. Other directors are total control freaks who reign like kings over the acting, camera work, set design, music, editing, and so on. You can choose how much of what you want to do (and in many cases, you’ll be doing some of this yourself, like probably the camera work, so the directing will be all within your head).

Note

I strongly recommend you subscribe to this YouTube channel:

www.youtube.com/user/esotericsean (URL 2.25)

and watch all the episodes. It’s a filmmaking instructional series called Take0, which refers to everything you do before the first take. They teach all about planning, although they also cover what to do while shooting, and after, to make a great short film. They cover writing, planning, directing, acting, camera work, editing, and more. Two young smart guys make it, and they add new episodes regularly. They have more than a thousand subscribers.

I’m honored to know them and honored that they cite my $30 Film School book as an influence.

Motivation

Your first job as a director is to motivate the actors. Give them suggestions to bring the script to life. Or if it’s a looser, more improvised production, bring the outline to life. The best way to do this is to gently but firmly tell them what you want. The archetype of the screaming director is not one to emulate and, especially if you’re dealing with unpaid amateurs, will more likely result in people quitting with tears streaming down their faces than it is to result in a good performance. (See Figure 2-12.)

Try to coach your actors into giving you what you want. You have a vision; they are there to help bring that vision to life. Different approaches work for different actors. Some respond to sweet talk, some to a more emotionless pragmatic approach, some to being told to “picture themselves as the character.” A lot of directing is simply people skills, getting great work from people and sussing out the best way to do this with different people. Practice this, and keep track of what works and what doesn’t. You’ll get better with time at figuring out the best approach, to the point where it becomes intuitive the first time you meet someone and talk to them for a few minutes.

There’s effective video art that comes from a group directing mentality but I’ve found it’s not as good, and results in some degree of chaos, if one person isn’t in charge. If you have a clear vision and your actors are chiming in suggestions that aren’t helpful, ask them nicely to follow the script and your direction. If they aren’t happy with this, find different actors. If they’re decent actors but trying to run the show, and they’re also YouTubers or filmmakers themselves, you can say, “If you do this my way in my film, I’ll be an actor and let you direct me without commenting in your film.” Being directed by someone else, even a bad director, can make you a better director.

Directing the Camera

I saved the most fun part for last.

The other main part of what directors do, other than directing the actors, is directing the camera operator. The camera operator might be you in your YouTube videos, or it might be a friend. Regardless, you should understand the shots that make up most filmmaking.

Shots

The basic shots in Hollywood filmmaking are the establishing shot, the medium close-up, the close-up, and the over-the-shoulder shot. These shots are shown in Figures Figure 2-13 through Figure 2-17.

An establishing shot is a wide shot that shows the setting where the scene takes place. A lot of beginning filmmakers skip this, and that can be a mistake. If you start with a close-up of two people talking, the viewer has no frame of reference for where the scene is taking place. This is not always needed; sometimes it’s all about the people. But in any story-driven piece, consider whether the location is important. If it is, you might want to consider starting the scene with an establishing shot.

A medium close-up shot shows a bit of the background of the setting but comes in closer on the people talking. This is often where you “meet” the characters for the first time.

A close-up shot shows more of the mood of the face of one character. It should be used sparingly because it can be a little intimidating. It is often good for showing a reaction, especially of shock or surprise.

An over-the-shoulder shot is often used to show the face of the person speaking, while putting it in the context of the other person listening. It can be overused and grows tiresome quickly, especially if you switch angles every time each person speaks.

Here’s a great tutorial on using different shots (see “more info” on the right to see which shots show up at each time point): www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpPWdgGa28k (URL 2.26). You can also use different camera angles to accomplish different feels. Here’s a good tutorial (from the Take0 folks) on camera angles: www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLfI4DQIAaY (URL 2.27)

Tripod or No Tripod?

You can buy an inexpensive tripod for your camera. A tripod stabilizes the camera. (You can also just set your camera on a stack of books if you don’t have a tripod.) Shots from a stabilized camera can look more professional, or they can look stale. Handheld shots (where you’re holding the camera rather than stabilizing it with a tripod or other object) can look exciting and add energy, or they can feel jittery and amateurish. Figure 2-18 and Figure 2-19 illustrate tripod and handheld camera use.

Here’s a video that was taken using handheld camera work that looks good: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_kWmZG1zdE (URL 2.28). It’s Alan walking around his apartment, vlogging while holding the camera.

Experiment with both stabilized and nonstabilized camera work, know what each can do, and add it to your list of tools to get the exact right look for every moment you commit to video. As the director, you are calling the shots, literally, whether you’re directing someone else with the camera or doing it yourself. It’s all part of getting your vision onto the tiny screen and potentially out in front of millions of people.

So, there’s your crash course in storytelling and directing. Got that? Good. Time to move on to actually committing your stories to the camera and then getting them up on the ‘Tube.