4.

Where Are You in the Business Lifecycle?

One of the key goals of this book is to identify—and then act on—the red flags warning you that your company or business unit is broken before the issues at the core of its dysfunction become life threatening. While knowing which of the four reasons a company might be failing—rudderless leadership, complacency resulting from the lust-to-lax syndrome, incompetence, and using conventional thinking rather than thinking outside the box to thrill (more on that later)—is affecting your business, it’s also important to know what phase of business your company is in.

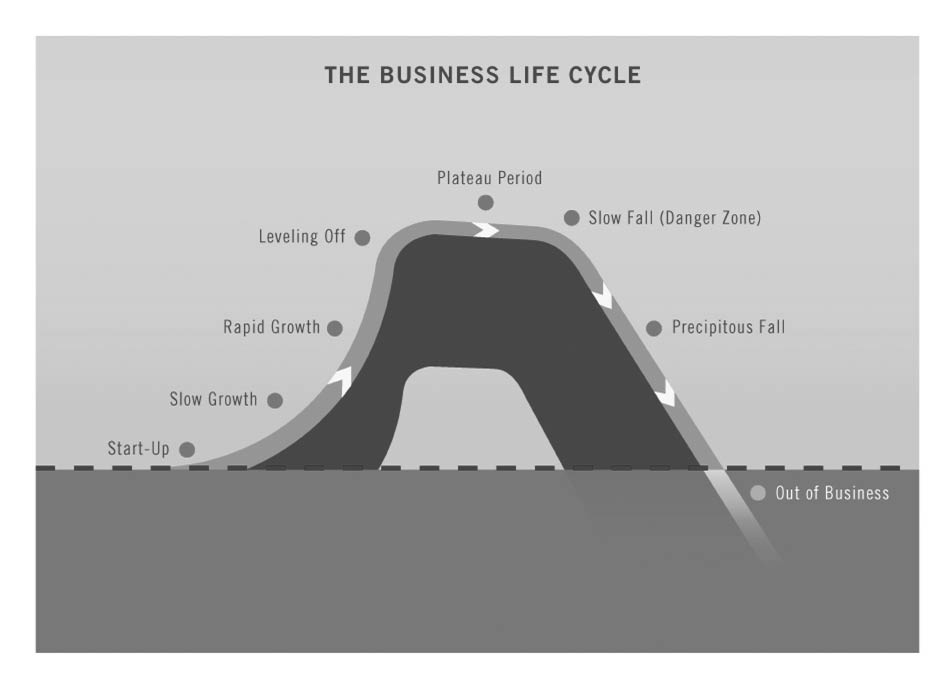

Virtually all companies move through a similar business lifecycle to varying degrees—and the hope is to avoid phases four and five. The cycle is rife with issues, challenges, and opportunities that must be addressed as the business evolves.

The Five Phases of the Business Lifecycle

Where are you in the cycle?

1. Infancy.

Phase 1 Traits

- Exploratory stage

- Establish identity

- Develop code breaker

- Implement structure

The company is formed and grows slowly. It is finding its sea legs, testing messages, experimenting with product selections, and deciding on the proper array of products and services to offer in the marketplace. Consider this an exploratory stage where the initial idea for the business meets the reality of structuring it and facing the unforgiving and, if you are open to it, extraordinarily valuable feedback of the marketplace.

Of course, there are exceptions, but as a rule, this nascent stage is not marked by a skyrocketing trajectory. The wise business owner uses the early stage to carefully observe how the business is playing out, as founding ideas and concepts are transitioned to pragmatic application. The goal is to develop what I call a code breaker—that combination of product/service, pricing, and marketing that lights a fire under sales and leads to scalable and sustainable growth.

When I first launched my current company, MSCO, I focused on charging for so-called marketing deliverables—brochures, newsletters, direct response mailers, print advertisements, and the like—and threw in my strategic thinking capabilities for free. It seemed to me to be the best way to offer a high-value service that my competitors could not match.

It was. But there wasn’t a single good reason not to charge fees for the substantial business insights I was delivering. So in this early stage of the business, I hit upon the code breaker for my company: focusing on being one of the few marketing firms capable of developing business growth strategies, leading with this, making this the key driver of revenue, and moving the deliverables to the back of the supply/value chain.

The seeds of problems that will come to plague the business in the future are often planted in the slow-growth early years.

Additionally, the lines of authority between the friends are not clearly delineated and, as others come into the company, they, too, are caught up in the fuzzy logic that becomes the foundation of the company’s culture. It can all feel warm and clubby in the nascent stages, but this turns to chaos as the enterprise adds people and complexity to the mix.

I worked with a hair-products manufacturing company launched by some Syracuse University grads who were onetime sorority sisters and fancied themselves as tighter than blood sisters. In terms of friendship they may have been close, but business and friendship are hardly one and the same. They didn’t understand the distinction. To their way of thinking, running the business as if they were still cruising around campus in the coed years would be the secret sauce for an extraordinary company, the winning recipe to set them apart from the competition.

At first, the spirit of kumbaya worked like a charm. There was a warmth to the enterprise, a sense of belonging, and a quasi-family ethos that left everyone feeling like they were owners. This is nice in theory but horrific in practice. Why? Because what started out so peachy didn’t stay that way. Fast-forward to 2011, ten years after the company’s formation. How is this for a friendship gone awry?

First, the salesperson covering the company’s most important territory—New York’s boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens—lives in Stockholm. Yes, as in Sweden. When Patricia’s husband was relocated to that charming Scandinavian city, Pat naturally wanted to go with him…without giving up her job at the hair products company and without parting ways with her “sisters.” And so they all agreed that she could maintain her New York sales territory, move to Sweden, never see a customer again, and collect her salary in full. She would call the salons once a month, taking the orders she could get, and call it a win/win. (Yes, sometimes truth really is stranger than fiction.)

Second, when customers made it clear that they wanted new products to complement the existing line, the founders sent out the word to the most innovative sisters, those charged with developing new products, to come up with the winners that would blow away the customer base and the competition.

The response? Zero! No one even bothered to get back to the founders. Why? They were sisters and, unlike in a corporate structure, where employees must answer and respond to the boss, sisters can choose to ignore each other—which is precisely what they did. Case closed.

2. Accelerated Growth.

Phase 2 Traits

- Growth begins

- Solid leadership guides the company

- Disciplined environment exists

Management does something or many things well, and the business takes off and grows rapidly.

Consider this the by-product of the experimentation and testing done in Phase 1. As the business gains more structure and begins to identify its best skills, as well as home in on its sweet spots in the marketplace, growth accelerates markedly.

Admin Server was once a small tech startup in the financial services space, founded by two software pros with a game-changing idea for bringing new products to market far faster and less expensively than traditional means allowed. This would be a boon to every company engaged in the development of insurance, annuities, and investment instruments, as the first to market often commanded the highest share of sales for years.

When my friend Rick Connors’s firm, The MONY Group, was acquired by AXA, Rick earned a handsome payout and decided to transition from the executive suite (where he ran MONY’s annuities business) to an entrepreneurial venture. Connors, who had installed the then-fledgling Admin Server’s product when he’d worked at MONY, decided to join Admin Server as president. With Rick’s management and leadership skills, he was able to give the company the structure and discipline it needed to rocket past the start-up stage, to expand more than tenfold in two years; soon thereafter, it was acquired by Oracle.

In short, Connors was able to whip a smart but ragtag organization into a selling machine that experienced dramatic growth and quickly commanded a substantial market share.

3. Leveling Out.

Phase 3 Traits

- Growth stops

- Complacency is a danger

- Management is not adapting to change

- There’s still time to turn it around

The high-growth period runs its course and the business plateaus. What does the plateau stage look like? Here are the signs:

- Revenues have either leveled off, are declining slightly, or the pace of growth has slowed markedly. In many cases, the last sign is the most dangerous. Why? Because the company is still growing (albeit at a more modest pace), so it is easy to overlook the problems that may be looming over the business. But look you must: there is a reason the pace has slowed considerably.

- Customer complaints are on the rise. It’s nothing like a full-scale revolt, but for the first time, you are hearing a rumbling of discontent. The temptation is to address the complaints as isolated incidents, but once the drumbeat becomes steady, the plateau—and likely worse—is just over the horizon.

People always want to earn more, but as a company begins to decline or settle into a plateau period, the culture suffers and the sense of excitement that comes with being part of a mission begins to deteriorate. In this environment, where the intangibles lose their value, the chorus of voices seeking raises expands dramatically.

- Employees are seeking raises in greater numbers than usual. It may, in fact, seem that everyone wants a raise at the same time. Of course, people always want to earn more, but as a company begins to decline or settle into a plateau period, the culture suffers, and the sense of excitement that comes with being part of a mission begins to deteriorate. In this environment, where the intangibles lose their value, the chorus of voices seeking raises expands dramatically.

Think of it this way: no one serving passengers on Southwest flights makes big money but virtually all are proud and happy to be part of the best team in the air. The day that changes—that flying Southwest is the same miserable experience as suffering on Continental or United—management needs to read these tea leaves as the signs of a plateau.

The great thing about a company at a plateau is that it has not yet taken a nosedive into the disaster zone. The plateau stage is salvageable, and it’s where my company often comes in to do damage control and retool things.

My goal at MSCO is to take hold of the runaway business and begin to engineer a turnaround, well before the free-fall period, ideally at the plateau stage. A business entering or already in the plateau stage of its lifecycle emits a set of signals that—if you are vigilant and willing to read the writing on the wall and accept it for the bad omen it is—can help you respond before conditions deteriorate.

It helps to understand how you got to the plateau in the first place. Typically, the plateau occurs because the business does one or more of the following:

- Fails to refresh its offerings. The hot products or services that launched the business and provided its initial thrust have lost their appeal. For example, there was an eyeglasses chain of five stores that hit a major code breaker with a punky/hip-hop look that appealed to young people (and those not so young but determined to retain the illusion of youth); it rode the crest of the wave for three years, opening new stores at a rapid clip. But the fashion wheel always turns, often quickly and unexpectedly, and when it did, the chain found itself saddled with an image, inventory, and a myopic management mindset that was hurting the business, locked as it was in the straits of yesterday’s look.

- Lacks resilient managers. Management is often a cause of a business’s plateau issue rather than being part of the cure. That is because managers/owners tend to dig in during times of stress, believing (when the tide begins to turn) they are in a battle with customers as opposed to being in a form of partnership. Wise businesspeople recognize that they are not in a war of wills with their clients/customers; instead they’re locked in a battle to stay ahead of the inevitable curve that brings new styles, products, services, offers, pricing systems, and the like to the marketplace. When management is driven to resist rather than revise, the company plateaus.

- Suffers from complacent managers. Management also can fall into the complacency trap, believing that a company’s rapid growth period implies a lifelong guarantee of continuous, high-octane increases in sales and revenues. This is why early success can be a blessing and a curse. To prevent this entitlement mentality, and, in turn, the plateau that comes with it, management must wake up every day determined to be, as Michael Dell has said, “the biggest start-up in the business.” Expect nothing, but fight for everything.

4. Slow Death.

Phase 4 Traits

- Slow death begins

- Management walks around in a haze

- “Hope springs eternal” employees fail to face reality

The company begins to go out of business slowly. Management, confused and disoriented like a pilot in fog, has failed to deal effectively with the flattening company trajectory that occurred in Phase 3. Accordingly, the company begins to shrink.

The telltale signs include:

- Declining sales that can no longer be dismissed as an aberation. The downward direction is clear and appears to be unstoppable.

- The best team members flee, leaving the company to join competitors or to become competitors in their own right.

- Customers vent their anxiety that something appears wrong wtih the company—and they actually worry about engaging in long-term contracts with it.

It happens so gradually that the first signs of possible demise go undetected by you or your managers (who are in denial or so irrationally optimistic that they believe—with zero evidence to support this—that “next year will be better. Next year will be better. Next year will be better…”).

There is both good news and bad news in this fourth phase of a business. The most dangerous part of the corporate lifecycle is the very point when the company begins to go out of business slowly—but it’s also the point where the process is the most reversible. So if you’re at this point, it’s not too late to turn the tide. The key is to recognize the plateau, not wait until you’re free-falling.

5. Major Free Fall: RIP.

Phase 5 Traits

- Company burial is imminent

- There is a controlled state of panic

- Employee morale has tanked

- Leaders are angry

- Loyal customers are being punished

The company begins to go out of business rapidly, often in free fall. The end is near. This last phase is usually marked by a state of chaos:

- The boss is mad but doesn’t quite know who to vent her anger at.

- Customers who have remained loyal to the bitter end are rewarded with harsher credit terms and deteriorating products and services.

- Employee morale, already on the ropes for some time, turns to outright bitterness followed by a rush to the exit doors.

- The place is a virtual disaster zone.

- Cash flow is negative, inventory is sparse, and employee count has dipped below the point that customers can be well served by even the most modest standards.

- In a typical day, everyone is spending 90 percent of the time trying to put out fires—and for every blaze that is extinguised another takes its place.