Chapter Twelve

Case Study 2

12.1 The ZEDpod at BRE Innovation Park, 2016.

It has become notoriously difficult in recent years for graduating students and young professionals to break into the property market. As a result, they are forced to spend more time and money in rented properties than they would wish, and the problem is made worse in built-up urban environments because prices are so high. The pressure on a decreasing area of central urban space for property developments comes at a time when there is increased pressure to ensure that the environment does not suffer as a result of people’s behaviour. This case study outlines a potential ‘step-up’ option for people wishing to enter the property market, while showing how a more considered use of urban space can be combined with ways of creating affordable homes, all potentially avoiding net annual energy bills (fig. 12.1).

Introduction

As cities expand, the edge of the built-up area tends to attract light industrial uses, usually with associated workers’ housing. Because these areas are rarely served by public transport, we find very large car parks for workers who come here from large high-rise dormitory suburbs (fig. 12.2). It is not only light industry that offers this opportunity. Hospitals usually have large car parks, while at the same time there is a concern for providing affordable housing for nurses and junior doctors close to their jobs.

12.2 Affordable homes ‘walk’ to the next ring as city centre property prices escalate.

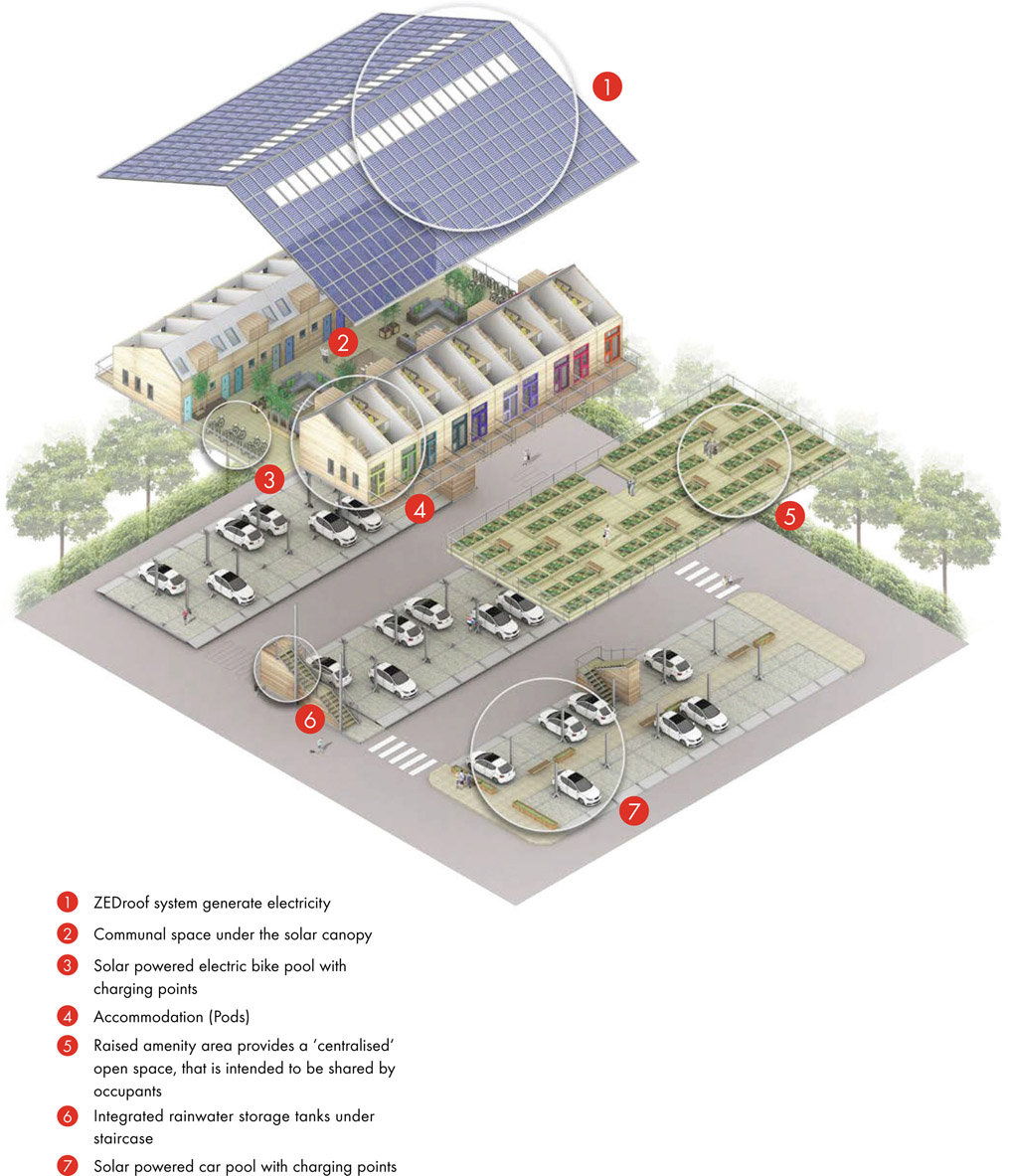

The ZEDpod is a proposal for creating alternative living accommodation next to the workplace in ‘pop-up’ workers’ villages above these parking areas, so that for these workers, at least, commuting becomes a thing of the past.

The roofs of these villages can become a waterproofed rain-shedding solar farm, making it possible to power electric cars and scooters directly from sunlight, reducing emissions from conventional fossil-fuel powered vehicles in the process. This could remove the need to build ground-mounted solar farms over premium agricultural land. In the process, this proposal would increase local air quality.

The housing pods and the workplace structures can be designed to be demountable so that if the workplace moves further out of an expanding town, the housing can follow.

What is a ZEDpod?

The ZEDpod is an affordable starter home using air rights over existing parking lots, so incurring no direct cost for land. This is what makes them different, and enables them to cut the knot of unaffordable housing. These homes, built with high energy-efficient performance standards that exceed the building regulations, have the added attraction for residents of avoiding net annual energy bills.

Because they are prefabricated in a factory, construction time is shorter without affecting the durability of the pod. It is a durable, permanent construction that, unlike other permanent homes, can easily be relocated with minimal wastage.

Where can the ZEDpod be used?

Since the pods are built on elevated platforms in car parks, there is no need to buy the land, or to take away any of the land already allocated to housing. Equally, there is no need to release greenfield or green belt land to meet housing targets.

Who is the ZEDpod aimed at?

The ZEDpod is a small, low-cost energy-efficient home intended for young professionals, singles or couples wishing to get on to the property ladder or seeking genuinely affordable rental housing. Like all good housing, however, it will work for anyone. In terms of size, single pod units can be combined as double pods, creating two-bedroom homes or even larger combinations.

How does it work?

With their integrated solar PV panels (ZEDroof), the pod homes are more energy efficient than a building regulations home. They would be built from durable materials, avoiding the potentially harmful urethane foams, UPVC windows, high VOC paints and plastic water vapour barriers found in much conventional affordable home construction today. Water-saving showers and taps are fitted as standard.

These quality standards exceed those of conventional affordable homes which only meet the legal minimum of the building regulations. This is achieved at an affordable price by not having to purchase land and not having to spend large sums on infrastructure provision, such as services and foundations. That removes between one-third and half of the cost of providing a conventional home.

By super-insulating the pods and providing heat recovery ventilation and high standards of draught proofing, only very small amounts of space heating would be needed to make them comfortable. The biggest remaining heat demand would be domestic hot water, and this can be met by a tiny 400 W electric evaporator plate heat pump. This heat pump works like a fridge in reverse, circulating its refrigerant through an absorber plate fitted to the upper roof. No fan noise is heard. One unit of solar electricity will normally produce around three units of heat, enabling each home to be substantially powered by solar electricity generated by the photovoltaic roof panels. When massed together in sufficient numbers, the pods can create a solar farm without taking agricultural land out of use. Over the lifetime of the project we would expect that larger ZEDpod communities would have no net carbon footprint, and could offset both the carbon footprint of the original construction, plus the annual maintenance and annual energy needed to run the homes (fig. 12.3, overleaf).

The solar electricity produced during the day would be stored in a large 60 kWh LiFePO4 store with integrated inverter that can power the homes at night. On the rare occasions when solar radiation is low in mid-winter, the battery store could automatically trickle-charge itself during the day from the street light circuit. This way, the unwelcome cost of digging up the car park to install new electricity supplies can be avoided. There should be enough excess renewable electricity to charge a number of electric vehicles during the day (fig. 12.4, overleaf).

The interlocking array of solar panels provides the roof surface and covers the access decks, a cost that would more than pay back the initial investment. The increased demand on the local electricity grid will be barely noticeable, so that however many new homes are built this way there is no need for new power stations and new cables. With the provision of grey and black water handling on-site, there is likewise no need for new water treatment plants or to put stress on existing ones. This saving in centralised infrastructure provision can both

12.3 Pop-up community that uses existing parking to create accommodation, generate electricity and de-carbonised urban mobility.

make sites viable without good mains services, thus saving investment by the local government and local utilities. An off-grid drainage strategy can also be deployed where necessary, which leaves a fresh water supply and a street lighting circuit to tap into as the only conventional services required. In this manner, a totally off-grid lifestyle can easily be achieved at a modest extra cost.

12.4 Electric vehicle charging point at BREpod.

Are the pods large enough?

The pods have been designed to sit over existing areas of tarmac-covered parking bays. By necessity they must respect the bay size of a typical parking space. This is either 2.4 m wide and 4.8 m long, or more recently 2.5 m × 5 m. The support columns for the pod housing sit between parking bay spaces, spaced to allow the car front doors to open without obstruction. Rubber ‘D’ profiles stop careless drivers causing any impact damage to the support columns (or to their own cars). It is, admittedly, a rather tight and narrow shape, but we believe that any perceived disadvantages can be overcome by careful thinking about the quality of interior space and its connections to outdoors.

By taking two back-to-back bays, we get a planning grid of 2.5 m × 10 m, which is enough space to fit a 22.4 m2 pod with a generous private balcony on its living room side, and a generous communal access deck to its front door (figs 12.5–12.8, overleaf). The pods do not touch each other, and a small fire-proofed cavity between them prevents sound and impact transmission between party walls. Placing up to 12 pods in a line with a shared staircase at each end provides good fire safety and allows the bin stores, batteries and water treatment tanks to be integrated with the staircases (fig. 12.9, overleaf).

A roof-light window gives direct light and ventilation to the bedroom. A generous wraparound desk makes a good home office space, which looks down on the living room, suitable for students or anyone else wishing to work at home. Each pod can have 7.5 m2 of shared communal space below the raised roof solar canopy, and some of this can be enclosed, if required, to make a shared living room of the kind needed in co-housing. This is achieved economically by adding a vertical glazed screen at either end, thus enclosing the space between pods.

Another plan variant, measuring 60 m2 including a share of the communal space, consists of a double pod with two large bedrooms, a larger living room, kitchen and bathroom (figs 12.10–12.11, overleaf). This would meet the recommended national affordable homes space standard should this be insisted on by the planners.

12.5 Section view.

12.6

Single Pod Plan.

12.7 Double height space.

12.8

Open plan kitchen and living space.

12.9

A single Pod terrace.

12.10+12.11 ZEDpod at Shanghai Design Week, 2016.

12.12 A double terrace with a solar lobby in between, with vehicular access either side, as well as directly underneath the lobby.

Providing future flexibility for landowners

All landowners want to maximise the value of their land. The trouble is that many vacant sites or car parks are seen as possible long-term development opportunities, so they are left empty for 20 years or more as land speculation. This less-than-ideal process of urban regeneration needs to be recognised and understood by local communities, because a site could be used to support a temporary use for a minimum of five years, a timescale corresponding to a temporary planning approval. Providing the community can be rehoused on another comparable car park, and the rental income from the pods continues to flow to the investors that funded their creation, the attraction of this bonus profit could be expected to unlock many underused urban sites (figs 12.12–12.15). While this idea depends on the availability of another site when it is time to move on, most local authorities or large landowners owning a large number of car parks should be in a position to make this commitment (figs 12.16–12.18, overleaf).

12.13

Communal space under the solar canopy.

12.14

Communal lounge with kitchen and dining area.

12.15

Electric vehicle charging points in line with SHS columns. One charge point for each parking bay.

12.16 Inserting the ZEDpods’ urban system into a car park located next to a suburban railway station and surrounded by low rise Victorian terraces.

12.17 144 ZEDpods applied to a supermarket or retail park context.

12.18

Shared ZEDpods’ communal space on decking placed over the roadway access to the parking spaces below. The glass tables double as light wells to the covered parking bays.