7

One to One Thousand

Today, digital fabrication tools are more than just accessible. They’re also powerful.

I didn’t notice it during the initial classes I took. At the time, it just seemed like learning; everything was new and interesting and overwhelming. The first three hours of laser cutting look a lot like the first three hours of any manual skill, like wood carving or welding. It’s a period of constant absorption and productive struggling.

But that’s not where the digital fabrication tools shine. Having their design DNA embedded into bits means that it’s cheap and easy to create an exact copy. Getting to the prototype or mock-up stage always takes effort, whether digital or analog. With a digital design, though, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel for the second revision. The leverage isn’t going from zero to one—it’s going from one to one thousand (or even several thousand).

Although it requires more up-front design time, the amplified production capacity afforded by the computer-controlled machines means that making many (anywhere from hundreds to thousands) of one design is relatively straightforward. This is beyond prototyping. As many new makers are finding, this micro-manufacturing can lead to some interesting and exciting business opportunities. The challenge, as with all business, is finding a market for those products. But makers are learning that, too. In the same DIT style used to learn the new tools, we’re helping each other to turn these projects into burgeoning enterprises.

Perhaps nobody has lived this Maker Dream more authentically than Abe and Lisa Fetterman.

Sous Vide Dreams

Abe is tall, thin, soft spoken, and whip smart. He has a degree in physics from Caltech and a PhD in astrophysics from Princeton University. His laid-back attitude and kind demeanor make him approachable and engaging. He’s shy and humble and intellectually intimidating. A conversation with Abe leaves you more confident in the human race but sharply reminded of how little you know.

Lisa is the most outgoing person I’ve ever met. She’s Chinese-American, with a pair of thick-framed glasses and a huge smile. She has that rarest of abilities: she makes you feel both uncomfortable and comfortable at the same time. Her filter-less commentary keeps you on edge, but her smile reassures you that there’s a heart full of kindness behind the gregarious shell.

If you met them separately, you’d never pick them out as a match because of their wildly different personalities. When you meet them together, though, you wonder how they ever lived apart. They’re a dynamic couple, and their attraction is magnetic.

I first met Lisa and Abe at the World Maker Faire in New York City. They were our neighbors for the weekend, with our booth for OpenROV adjacent to their Arduino-powered, DIY sous vide cooking device. They drew a much bigger crowd than our project, mostly because they were serving up deep-fried egg yolks to anyone who passed by. Of course, people were interested in the fried egg yolk, but more so, they were attracted to the energy and passion of Lisa and Abe.

Over the course of the Faire weekend, we shared a few pleasant conversations, but we were both so busy with fairegoers that we didn’t have time for much of an extended conversation. It wasn’t until a year later, while on a story assignment for Make: to cover the Haxlr8r demo night in San Francisco, that I would again cross paths with Lisa and Abe—only this time, the circumstances were very different.

The demo night was the culmination of the Haxlr8r program, a 15-week boot camp for budding hardware entrepreneurs that took them from the factories in Shenzhen, China, to the venture capital offices of Silicon Valley. The program was the first of its kind: a startup accelerator that took advantage of the new rapid-prototyping environment to help aspiring entrepreneurs make their products along with a properly organized business. I sat in the front row, jotting down notes for the blog post. I found all the pitches and demos to be of good quality, certainly more interesting than the countless number of app-making or Facebook-clone startups you run into around San Francisco. When Lisa took the stage as the final presentation, my heart fluttered with excitement.

To say I was shocked would be an understatement. It wasn’t just that I was surprised to see them, but to see how far they had come in only one year was hard to wrap my head around. They had turned their hacked-together DIY kit into a beautifully designed kitchen product—something you could envision buying at Target or Bed Bath & Beyond. As it turns out, the full story of how they went from DIY amateurs to Food Network–ready entrepreneurs completely lived up to my demo-night amazement.

Two years earlier…

Lisa and Abe were both living in New York. Abe was working as an astrophysicist and Lisa was studying journalism at NYU. They had been dating for about a week when Lisa made an offhand comment about wishing she could cook sous vide in her apartment. Sous vide is a method that involves slow-cooking food inside a plastic bag in a water bath at a precise temperature over long periods of time. It was popular among the high-end chefs that Lisa admired, but the home-use machines were prohibitively expensive. Abe, ever the enterprising swooner, promised he would make her one. He didn’t have any experience in this type of endeavor, but he possessed plenty of confidence nonetheless.

At this point in the story, neither of them knew how to solder.

Their lack of relevant education and basic making skills didn’t slow them down one bit. With a reckless but admirable confidence, they threw themselves into the project of creating their own sous vide machine. It wasn’t long before they had created a makeshift device. It consisted of only $50 in off-the-shelf parts (and involved no soldering). They published their design on their blog.

“We thought it was going to blow up the Internet, but nobody came,” Abe confessed to me. Their design, even though it was the lowest-cost DIY sous vide around, didn’t get much attention.

They kept building. Soon, they had created an improved DIY model that could be built for $75 in parts. But, again, not much attention.

It wasn’t until a chance encounter in a Manhattan coffee shop with Mitch Altman, all-around maker superhero and creator of the TV-B-Gone, that their story took a turn for the wonderful. At the time, Abe and Lisa didn’t know about Make: or Maker Faire, or who Mitch was. They were just sitting at a nearby table as Mitch was being interviewed by Matt Mets. They overheard the entire interview, and after it was over, they approached Mitch.

“Hey! We’re makers! I think…” Lisa said to him.

Mitch invited them to a soldering class he was teaching at Alpha One Labs and Lisa took him up on it. With the knowledge she learned there, and some Arduino skills they picked up at NYC Resistor, they designed a DIY sous vide kit called the “Ember” and began selling it for $80.

I stopped them at this point in their story. I was doing the math in my head, “Wait, that must have been a slim margin on your kits. Right?”

“Oh, certainly. There was no margin at all. We just wanted everyone to be able to sous vide,” Lisa told me. And they did. They made their kit as easy to assemble and use as possible. If it was something they could figure out, they thought, then anyone could do it. They started teaching classes at Alpha One and NYC Resistor to anyone who was interested. While teaching one of their classes, they met a native Thai chef who was working in the city, Bam Suppipat (he comes back up later in the story).

Pretty soon, life got in the way of their sous vide dreams. Abe got a job in San Francisco and the couple relocated to the Bay Area. Lisa also began working a new job. Their passion for cooking seemed as though it would always remain a hobby.

But they missed it. After seeing a write-up about the Haxlr8r program, Lisa and Abe decided to go all-in on their sous vide idea and try to turn their dream into a business. They were committed and now they had no other options but to try to make it happen.

Once they were in Shenzhen, China, everything became harder. They were quickly running through their seed capital and had very little to show for it. Out of ideas and stressed about their project, they decided to take a short trip to Thailand to clear their heads. They called the only friend they had there, Bam, and asked him to show them around.

During their first night with Bam, they explained their sous vide project and all the challenges they were facing, technically and emotionally. As it turned out, he was the perfect person for them to confide in. In addition to his studies at the French Culinary Institute, unbeknownst to Abe and Lisa, Bam also had an industrial design degree from the Rhode Island School of Design. His life’s dream was to design better culinary devices and equipment, but he had recently resigned himself to moving back home to Thailand and taking a stable corporate job. Even though he was stuck in a cubicle during the week, Bam was still cooking and teaching low-temp cooking in Thailand on weekends to home cooks.

It was a match made in heaven.

What started as a friendly evening of catching up quickly turned into a full-blown design intervention. The team spent the next three days reviewing, designing, and imagining what would eventually become the current Nomiku design. Abe and Lisa headed back to Shenzhen with a renewed sense of determination, and Bam, who still couldn’t believe that his dream job had fallen into his lap, joined them.

The team spent the next month building, developing, and sourcing the design that became the Nomiku Sous Vide Cooker. By the time the Haxlr8r program came to an end, they were ready to take the next logical step for any maker business: put their project on Kickstarter.

When I saw them at the demo night, they were closing in on having raised $100,000 of their $200,000 funding goal. By the time the monthlong Kickstarter campaign had ended, they had garnered more than $586,000 from over 1,800 backers.

What started as an offhanded comment from Lisa to Abe had turned into a fast-growing company. They, quite literally, created a multimillion-dollar business from off-the-shelf parts and the courage to follow their passion.

Define Your Own Success

Of course, Lisa and Abe’s story is uniquely theirs, just as your maker story will be uniquely yours.

The goal of re-skilling yourself doesn’t need to mean being an entrepreneur or building a business like Lisa and Abe. Re-skilling can be a powerful and effective way to find a new job or advance your career. It’s also perfectly wonderful if making remains a hobby, something done on the side for fulfillment and enjoyment. Or maybe it’s something you’re doing to help arm your kids with skills for the future. It’s all up to you. The best part is that you don’t need to have a plan when you get started.

Regardless of whether making turns into a fast-growing startup, a small lifestyle business, or an enjoyable hobby, it all looks the same for new makers—makers like me, Lisa and Abe, or you. It starts as an exploration and, as such, requires a mind that is open to new ideas, new people, and new possibilities.

If you’re looking to make a business or career out of being a maker, here are some important things to consider:

- Make something that excites you. I know this advice is played out, but I mean it. All the interesting and successful makers I know, especially the new makers who have picked up rapid prototyping skills in the shortest amount of time, are wildly passionate about and interested in whatever they’re making. Lisa Fetterman loves food and cooking. Eric and I are excited about oceans and exploration.

- The opportunity for digital fabrication tools and online communities to reimagine and redesign the built and “made” world is ripe. It’s a big, open field waiting for maker entrepreneurs to fill in the gaps. As you look to stake your claim, why not seize the moment and do something you’ve always dreamed of? The passion is the secret sauce, and it’s what attracts the help, from the local maker scene as well as the larger global community of interest. In the end, it’s the size and enthusiasm of the community that determines whether the effort is worth turning the corner and becoming a business.

- Also, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that starting a business is hard. No matter how passionate you are, or how easy the tools are to learn, or how low the barrier of entry to distributing and selling your product, it’s still a long, uphill slog. It’s always harder than it looks. A maker business is no different than a regular business in that respect. It’s only manageable if you’re passionate about what you’re building.

- Decide what matters. In the era of micro-manufacturing and small-batch production, the goals don’t necessarily need to be about making gobs of money and taking a company public. In fact, that’s my favorite part about the next industrial revolution. It’s less about enriching and enabling a select few manufacturers to become large, and more about allowing a larger number of niche manufacturers to remain small. The economics of being a small business finally work for the manufacturing sector. In Makers, Chris Anderson noted the following:

What’s interesting is that such hyperspecialization is not necessarily a profit-maximizing strategy. Instead, it is better seen as meaning-maximizing.

- Eric and I have always been clear that the OpenROV project, even though we’ve become a company and are selling kits—and now finished underwater drones—was never about maximizing profit. We’re trying to maximize our Return on Adventure; we wanted the project to add something to our lives and the lives of everyone in the OpenROV community. The strategy has paid off. Of course, we’re leaving a lot of money on the table by selling the kits at the lowest price possible, but we’d rather more people have access to the ROVs. We’re probably leaving ourselves open to cloners by posting our design files, but it’s allowed us to meet and collaborate with like-minded people all over the world. We’ve been invited to dive with NASA at their underwater reef base off the coast of Key Largo as well as join scientists as they study whale sharks off the coast of Mexico. We might never become millionaires because of OpenROV, but we’ll certainly have the ride of our lives.

Your maker business, like your maker journey in general, can be uniquely yours. The new playing field gives you the opportunity to maximize your own meaning, whether that’s time spent with family, a community of collaborators, or the freedom to travel. Whatever it may be, the best chance at achieving it comes from being intentional about it up front.

The new maker economy is about more than just making your own product or business; it’s about making your own meaning!

The Right Way to Use Kickstarter

As the saying goes, you don’t know what you have until it’s gone. This is a truism that Anton Willis faced when he decided to move to San Francisco. After growing up in Mendocino County in northern California, Willis was used to the wide-open spaces and outdoor recreational opportunities afforded to the rural lifestyle. This access to the outdoors, particularly to lakes, rivers, and the ocean, is what first fostered his interest in kayaking.

After he moved to San Francisco, however, his long fiberglass kayak didn’t quite work. He didn’t lack access to great kayaking space—there was ample opportunity in the San Francisco Bay. The real problem was that Willis’s small studio apartment didn’t have the space in which to store something that large. He was forced to pack the watercraft into storage and dream about another way to enjoy the water.

Months later, Willis’s daydreaming found an unexpected source of inspiration while he was reading a profile of origami physicist Robert Lang in the New Yorker. Willis wondered if he could apply the origami principles to his conundrum of needing a kayak that took up less space.

He set to work testing his hypothesis. He began with paper, folding up different design ideas until he had something worth prototyping on a larger scale. He worked his way through several dozen iterations on his way to a working prototype that he was ready to show the world, Oru Kayak (orukayak.com), likely the world’s first origami kayak.

Apparently, Willis’s desire to have a functional kayak—one he could pack neatly into a suitcase-sized package and quickly unfold for use—was a more universal need. He put the project on Kickstarter and raised over $100,000 on the very first day. The month-long campaign netted over $443,806, with 730 backers chipping in to support.

It’s the new American Dream: a person has a wild and creative idea, prototypes it until he or she gets it right, throws the project up on Kickstarter, makes gobs of money, and starts a new business. On the surface, that’s easy to digest. It’s the story all the blogs and magazines want you to believe. However, for new makers, this over-simplistic idea can be dangerous.

I’ve developed another perspective for thinking about the maker process, from idea to prototype, to product and business. I call it the maker-to-audience (M:A) ratio.

Admittedly, I didn’t come up with the term. I first came across this concept while perusing photos by Dan Parham, who had a series from a local Legong dance performance in Ubud, Bali. Although the photos were visually stunning, I was more impressed with Dan’s observation that there were 15 percussionists and 10 dancers entertaining a crowd of 10 people. An artist-to-audience (A:A) ratio, he noted, of 5:2.

My first thought was that the planning, preparation, and execution of a performance with an A:A ratio higher than one required an entirely different perspective on audience engagement. I imagined the Legong performers fixating on exactly how each member would perceive the performance. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the A:A ratio could be an important lens for all artists and makers to consider. The applications (and interesting milestones) spread far and wide in the realm of artistic creation as well as entrepreneurial endeavors, especially for makers.

It Always Starts with One

No matter how experienced a maker you are, every new project starts out with an audience of one: yourself.

In the past year, as I’ve explained my re-skilling story to other reluctant makers across the country, there’s a consistent excuse (one that I myself harbored for a long time) that seems to be holding a lot of people back: they don’t know what they want to make.

It’s profoundly common and perfectly reasonable. I mean, why would this newfound access to tools and expertise get anyone excited if they aren’t sure what they would use it for? It makes sense.

Most people jump to the conclusion that they don’t have any ideas for building something that other people would want. They don’t believe that they have a useful innovation or design that could be made and sold. When all of the Kickstarter success stories and maker businesses in the news talk of overwhelming product demand, it’s easy to be intimidated into thinking that that’s the definition of “making it.”

Don’t be fooled. All of the great maker stories (and correspondingly great maker businesses) that I’ve encountered have come from people or teams that made something that they themselves actually wanted.

Anton made the Oru Kayak because he couldn’t fit his kayak into his apartment. Lisa and Abe created their first DIY sous vide machine because they wanted to use the cooking technique but couldn’t afford the expensive commercial models that their favorite chefs were using. Eric and I never planned to be selling ROVs; it was always something that we wanted for ourselves so we could do our own exploring of the Hall City Cave. Making something you want is always the first step.

Over and over again, I hear stories of makers creating successful products and businesses as outgrowths of something that they personally wanted. Very rarely do I hear about a business that started from someone who set out to create something he or she thought had a very large market. If anything, that’s the ballgame for GE, Walmart, and other large manufacturing companies who have money to throw at focus groups and marketing campaigns as well as the production and distribution channels to deliver those high quantities.

It’s almost impossible to compete at that level as an individual. And, personally, I wouldn’t want to. Playing in the long tail end of the manufacturing scale allows for much more creativity. It allows commerce to happen at a more human scale. The trick to the new maker economy is finding your own unique niche. The best way to do that is to make something that you actually want.

It sounds easy enough: all you need to do is make the one thing you really want. But most people struggle with the magnitude of the question. In an op-ed piece for CNN (http://bit.ly/13OL4Vb), Jim Newton, founder of TechShop, talks about this seemingly simple question:

When I meet people who are not yet members of TechShop, I like to ask a simple question: “What do you want to make?”

The typical response is “Oh, nothing. I wouldn’t know where to start,” or “I’m not handy…I don’t know which end of a hammer to hold.”

Then I’ll press further. “Isn’t there something that you’ve wanted to make that doesn’t exist? For your house or car, a gift for someone, or to improve your life or someone else’s?”

That’s when an interesting thing happens. They light up and say something like, “Well, there is this one idea I have.” They will describe the idea in great detail right down to color, variations, and the brand name they have given it.

I’ve had a similar experience. I’ve found that that thing—the creation that a person really wants to make—is a few questions deep. It takes a little digging to get it out. As Jim mentions, there’s a light in their eyes that gives it away. Sometimes it’s something they’ve always wanted, and other times it’s a solution to a problem they’ve encountered. Sometimes it’s even a shared idea. For me, it wasn’t until I met Eric that I found a project that I could latch on to. This is common, too. With such diversity and possibility in the maker world, it’s impossible to predict what other makers might inspire in you, and vice versa. (I’ll talk more about that in Chapter 8, “Makers Going Pro.”)

Whether it’s something you’ve always wanted to make, or a project or group that sparks your interest at a local makerspace, keep looking until you find the project that lights you up. Coincidentally, it’s that internal fire that makes the learning process more engaging and, ultimately, rewarding.

To the Prototypers Go the Spoils

With some people, you don’t have to dig. When you explain the possibilities and opportunities afforded by the new digital fabrication tools, rapid prototyping techniques, and access to makerspaces, they know exactly what they would make. So it was with my friend Eric (a different Eric from OpenROV Eric).

Eric and I were having lunch together just outside of TechShop in San Francisco. I was there working on OpenROV, and his office was a block away. Eric and I hadn’t seen each other in months, and I quickly brought him up to date on everything that had transpired with OpenROV—the latest prototype, the Kickstarter project, and how we were building all of the kits. He was intensely curious. With his office next door, he knew all about TechShop but had never gone inside to look around. I explained the tools, with Eric taking a particular interest in 3D printing (as many new makers do). I also made a point to emphasize the ideas of DIT and Just-In-Time learning. It wasn’t long into the conversation before I had him convinced that he was totally capable of making anything he could imagine.

I asked him if he had any ideas of something he wanted to make. He didn’t say anything, but he looked slyly confident as he reached around to his back pocket and pulled out his credit cards wrapped in a thick blue rubber band.

“This,” he said. He flipped his tightly wrapped stack of cards around in the air and explained to me his obsession with finding a wallet that was small enough to fit comfortably in his back pocket. He’d been searching for the perfect solution, trying money clips and thin wallets, but nothing compared to his pleasure of using the elastic band. The only problem was that the rubber band would wear down and break every few weeks. He didn’t have any specifics, but he knew he wanted to create a better rubber band wallet.

Admittedly, I was a little unimpressed. Sure, everyone loves a thinner wallet but I never imagined a rubber band wallet meant anything more than a piece of blue rubber in Eric’s back pocket. I encouraged Eric to try to make it at TechShop, mainly because I wanted to get him in there and using the tools, but I didn’t think much about it after that.

It wasn’t until a few months later, while combing through different Kickstarter projects, that I would, again, cross paths with the rubber band wallet idea. I randomly stumbled onto a project called “TGT: A New Kind of Wallet.”

It was created by Jack Sutter. Jack first got the idea after seeing his roommate using a produce rubber band (taken from a stem of broccoli) as his wallet. He thought it was genius, and he wanted to take it to the next level. Another friend moved into the apartment and wanted to support Jack’s idea. She taught him how to sew and helped him make the first prototype of the wallet, which used a thicker elastic fabric with a striped design. Jack wanted to improve the design by adding a little pocket, so he met a furniture designer in NYC who let him take the leather scraps off the floor, which Jack turned into the next prototype design. Later on, after making numerous wallets, another friend helped Jack design packaging for his creations by cutting up an old cereal box. Around the same time, he had created a small logo for his new product, which he was calling TGT, and started sewing them into the wallets.

In a short amount of time, his inspiration had followed the winding and serendipitous path to becoming a quasi-product that Jack and all of his friends loved. The next logical step, of course, was for Jack to put the project up on Kickstarter.

Jack’s Kickstarter campaign was a huge success, raising over $317,000 from more than 7,500 backers. Apparently, there are a lot more people like Eric and Jack in the world than I ever could have imagined.

Of course, the first thing I did when I saw the Kickstarter project was send the link to Eric. He was also surprised to hear how successful the project had been. He was a little disappointed, too, that he didn’t follow through on his idea, but he was happy that the idea was finally out into the world.

I now refer to this story as my elastic wallet moment. I learned two important lessons from my conversation with Eric and watching the TGT Kickstarter campaign:

- Ideas are nothing; prototypes are everything. Eric knew he had a good idea. He even acted on it. He did extensive online searches, scoured retail locations, and bought relevant domain names. He thought about business models and marketing strategies. He went about the project in the traditional business way. Unfortunately, the new maker economy has rewritten the rules.

- With the increasing ease of creating (and actually starting to sell) a prototype, it no longer makes sense to think in terms of the traditional business routine. Of course, once it’s up and running, the same accounting, inventory, and manufacturing planning used by more traditional businesses is applicable. But as you travel the M:A spectrum from 1:1 to 1:2 to 1:10, the only thing that matters is a functional prototype.

- Prototype first, ask questions later.

- Sharing is the new first-mover advantage. Even if Eric had decided to create his own brand of elastic wallets (which he could definitely still do), he’d have a much more difficult time getting the same boost of support as Jack did on Kickstarter. There are only so many thin wallet enthusiasts within the Kickstarter universe, so running a successful project now would be an uphill battle.

- It’s hard to replicate the ripple effect that Kickstarter creates across the Internet. It’s a unique opportunity to magnify your project and broadcast it around the world. Unfortunately, it’s an opportunity for an idea, not necessarily your idea. I’ve seen numerous projects that failed to pick up traction on crowdfunding websites simply because there was a high-profile, similar project that recently tore through the Internet headlines and sucked all the oxygen out of the blogosphere. For instance, Twine was the first connected device on Kickstarter that aimed to be the platform for the “Internet of Things.” The idea was that the rooms and structures around us (and the things in them) should be connected to the Internet, and thus could be measured and controlled. In their Kickstarter video, Twine showed off their prototype sensing the temperature of a room, detecting motion and moisture, and other cool features that interested a wide array of backers. They ended their campaign with over $556,541.

- After Twine, Kickstarter has seen an influx of “Internet of Things” devices, and few have been able to live up to the hype and success of Twine.1

- The old adage about first-mover advantage was that the spoils belonged to the first product to get to market. In the new maker economy, where the value of your product or company is defined by how others share and contribute to your project and business, the first-mover advantage is given to the first project on Kickstarter.

1,000 True Fans and 100 True Believers

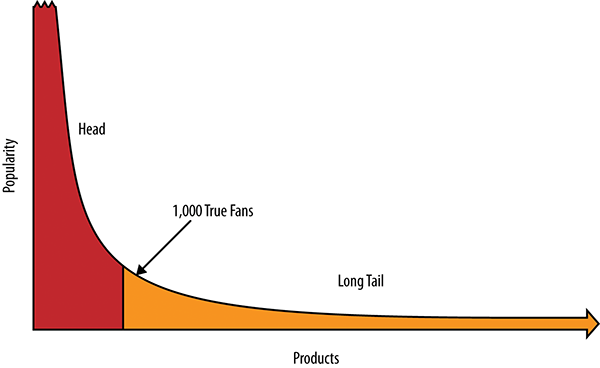

One of my favorite documented references to M:A ratios is Kevin Kelly’s theory of 1,000 true fans (http://bit.ly/14ydK4J). Kelly first articulated True Fandom in response to what he believed to be the artistic aftermath of the long tail, a creative middle class defined here:

A creator, such as an artist, musician, photographer, craftsperson, performer, animator, designer, videomaker, or author—in other words anyone producing works of art—needs to acquire only 1,000 true fans to make a living.

A true fan is defined as someone who will purchase anything and everything you produce. They will drive 200 miles to see you sing. They will buy the super deluxe re-issued hi-res box set of your stuff even though they have the low-res version. They have a Google Alert set for your name. They bookmark the eBay page where your out-of-print editions show up. They come to your openings. They have you sign their copies. They buy the T-shirt, and the mug, and the hat. They can’t wait till you issue your next work. They are true fans.

Kelly uses the graph shown in Figure 7-1 to orient exactly where this middle ground lives in relation to the blockbusters and “the quiet doldrums of minuscule sales.”

I love this idea. Not because I think that 1,000 fans is exactly the right number, but because I think it’s exactly the right idea. If your game is T-shirts, you’re going to have a higher number. If your gig is a highly custom and expensive sculpture, then maybe it’s much lower. It’s not the number, it’s the idea. If your product is revered enough to provide you with a living, it’s your job to sift through the other 7 billion people on the planet to find your 1,000 True Fans (or whatever your number is). For makers who aspire to carve out a career with their craft or product, this is a perfect target at which to aim their business aspirations.

Figure 7-1: 1,000 true fans (based on a graphic by http://kk.org/)

As much as I loved Kevin Kelly’s blog post, I have one problem with true fans as a theory. My problem is that it doesn’t look at fandom as a dynamic number, one that changes over time in direct correlation with your skill, experience, and exposure. The True Fan theory, as it stands, is that there are either 1,000 fans who’ll buy your work, or else you’re stuck. I think the minimum number of viable fans required to earn a living is an important milestone, but I think it’s important to examine other milestones along the way. More specifically, the 100 true believers.

Here’s my definition:

A true believer is someone who knows you as the person behind the art or product. Someone you’ve confided in by showing them your art or explaining your business plan. They care about your product because they also care about you. Not only will they buy your product, but they’ll tell everyone they know about what you’re doing; they’ll get the word out.

The 100 true believers are there before you hit the big time (or medium time). They’re the group that knows you personally, sees your budding potential—or that of your project—and wants to contribute to your future success. True fans don’t come overnight. It happens one fan at a time until you reach 100 true believers. They are the medium through which you’re able to attract and communicate to your true fans. Again, the number isn’t important. It could be 100, but it might also be 10. Before you can get to true fans, you have to establish your true believers.

With Kickstarter projects, I think the natural tendency for creators is to spend too much time thinking about the pitch and not enough time thinking about the audience. Not that the pitch isn’t important, but more time should be spent thinking about the audience. What is the goal? The goal determines the audience and the audience determines the pitch. To reap the full benefits of a crowdfunding project, you need to effectively understand where you (as a maker or business) stand in terms of an M:A ratio. Kickstarter can be an effective tool for multiple strategies, but there are two that seem to be most applicable: to develop your true believers or to catalyze them.

Developing Your True Believers

From the perspective of the casual observer, a Kickstarter campaign for a maker product is very similar to a product launch, an unveiling of a new device or invention to the world. It’s the maker version of Steve Jobs’s “And one more thing…” speech. Many naive makers (myself included) have made the mistake of assuming that Kickstarter works that way. They assume that you put up a video and the world beats a path to your doorstep. Unfortunately, that’s not quite how it works.

Generally, the surest way to be successful on Kickstarter is to have already developed your true believers. Building your cadre of true believers takes the hard work and elbow grease out of showing prototypes to the world and soliciting feedback. It doesn’t necessarily mean you need to broadcast your project in a public way, like a website or press release, but you do need to do the legwork of explaining your project to friends, to friends of friends, at trade shows, and, if possible, to influential people in your respective market. It can be a grind, certainly, but it’s the foundation that sets you up for future success.

This period, from an M:A ratio of 1:1 to 1:100, is critical. It cuts both ways, too. It’s an important time to find the first enthusiastic supporters of your idea and product, but it’s an equally important time for you as a maker to grow into understanding exactly what the market will support. It’s co-evolution; the world learns about you and your product, and you learn about yourself and the best way for your product to fit into the world.

Behind many of the seemingly overnight successes on Kickstarter are stories of a maker (or maker team) who worked incredibly hard to perfect her product.

Before Abe and Lisa launched their wildly successful Kickstarter project for Nomiku, they spent over a year on the maker circuit: showing off their DIY sous vide device at Maker Faires, offering kits and classes on how to build the kit, and continuing to improve and evolve the product. By the time they launched, no one on the planet knew more about low-cost sous vide machines and techniques. They knew Nomiku was truly innovative, and they had built a community of friends and supporters who immediately got behind the project.

When I first met Anton and saw his Oru Kayak almost six months before he launched his project on Kickstarter, I begged him to let me take it out for a test ride on the San Francisco Bay. We spent an afternoon paddling around Berkeley and I put the kayak through all the paces I could imagine. For a folded kayak, made from the same material as the political ads you see staked out in front yards, it was really impressive! I told Anton I wanted to write about my Oru Kayak experience on the Make: blog. He was hesitant, because he wanted to save any press opportunities for his upcoming Kickstarter project. I finally convinced him to let me write the story, and it ended up driving a lot of traffic and attention to his site and project, and he collected email addresses of those who expressed interest. By the time he launched his Kickstarter campaign, almost five months later, he told me that getting the word out early was one of the best things that could have happened.

To be fair, every once in a while, a Kickstarter project without the 100 true believers will break through to be a smashing Kickstarter success, like the PrintrBot. More likely, though, the success of the project is closely tied to the hard work and networking of the team prior to launching the project.

Catalyzing Your True Believers

Kickstarter or Indiegogo or any other crowdfunding platform isn’t the only way to turn your project into a business. For instance, it may be easier to sell on Etsy or start your own web store and sell directly (we use Shopify). But for those artists and projects that are ready, crowdfunding can be a great way to go from true believers to true fans in short order. In my mind, this is the true genius of the Kickstarter model. It’s much more fun to watch your project spin around the Internet by word of mouth than spend a month repeatedly having to remind your friends that you need their support.

As a thought exercise and gut check for knowing where you line up on the M:A ratio, try to make a list or map of 100 people who know what you’re doing and have expressed enthusiastic support (again, the right number might be 100 or it might be 25; it depends on the project). You might even send out a few emails telling those people that you’re preparing to launch a Kickstarter project and you’d love their feedback or input.

For our OpenROV project, the Kickstarter campaign was a long time coming. Eric and I started the project over a year and a half before our campaign. We invited anyone and everyone to join our community of DIY underwater explorers and enthusiastically shared our plans and designs. By the time we launched our Kickstarter campaign, we had collected a list of over a thousand people who had signed up on our site and expressed interest in building their own OpenROV. For us, Kickstarter was about getting to the next level by catalyzing our true believers. By taking the time to build support and involvement before the Kickstarter project, we were able to reach our funding goal within a few hours, which came almost entirely from the first email we sent to the OpenROV community.

Seth Godin, who ran a successful Kickstarter campaign for his book, came to a similar conclusion:

Kickstarter appears to be a great way to find fans for your work. You put up a great video clip and a story and wait for people who will love it to find you.

But that’s not what happens. What happens is that people who already have a tribe, like say the “punk cabaret” musician Amanda Palmer, use Kickstarter to organize and activate that tribe. Kickstarter is the last step, not the first one.

He’s almost right. Done correctly, Kickstarter isn’t the first step, but it’s also certainly not the last. It’s in the middle—the start of something new. It’s the beginning of having true fans, which comes with an immense responsibility to serve and deliver. It’s a lot of work. It’s the best imaginable type of work: co-creating with a group of people who share a common vision.

For OpenROV, the best part of the process has been exactly that. We’re working exclusively with them to manufacture and distribute kits to anyone interested in contributing. We found our True Fans only because of the amazing support from our True Believers.

Regardless of where you stand in terms of fandom, the first step of a successful crowdfunding campaign is honestly assessing your M:A ratio.

Prototypes as Products

The maker movement is doing more than organizing a community of manually literate collaborators and reducing the costs and barriers to accessing quality digital fabrication tools. It’s also creating a new swath of educated prosumers (producers + consumers) who place a higher value on the transparency and hackability of a product than they do on the price and performance. They care about the product and the process.

This new maker market is also more forgiving if a product (or project) isn’t polished or packaged beautifully. Instead, they’re more concerned with participating in the ongoing development. In addition to providing feedback and ideas for improvement, this maker market is eager to buy up the in-process goods. Essentially, it’s a market for evolving prototypes.

The old model of manufacturing and product development involved an innovative idea, expensive prototyping with designers and manufacturers, marketing budgets for the launch of the product, and expensive distribution channels to deliver the product to market. The maker movement has erased those barriers. More aptly, it’s rolled all of those steps into one public process that doesn’t take the intense capital expenditures inherent in the old manufacturing model.

The innovative idea is still a necessary catalyst, but the path in the new maker economy quickly diverges from there. Whereas the prototypes in the old model serve as milestones and expenses toward a finished and polished product, the maker model turns the prototyping process into a product and a social object used to educate and build community. The maker’s challenge is not to build a finished product, but to create something that is good enough and capable of getting better; the maker is designing for a perpetual state of becoming.

For more complex devices or inventions, this proto-product often takes the form of a kit. Chris Anderson and his 3D Robotics company got their start selling the ArduPilot boards and moved into quadcopter kits. For MakerBot, the first desktop 3D printers that they shipped were all kits that users had to assemble themselves.

The proto-product method has many advantages:

- It’s less expensive. On the business back end, creating and packaging a kit is far less labor intensive (and therefore less cost intensive) than creating a finished product. It’s possible to run a kit business with just a few people, as opposed to needing a manufacturing partner or assembly line. The kit business will have higher customer service demands, though, so it’s important to build the platform so the community can help educate one another. A wiki with thorough build instructions and an accessible FAQ section goes a long way in answering many of the most persistent questions.

- You learn more. Undoubtedly, people who build your product themselves will come up with different strategies, whether that’s due to education, available resources, or just sheer happenstance. The diversity of creation creates a Darwinian process that susses out the most effective way to build and use the product. To rehash the Michael Schrage quote from Chapter 3:

Talented amateurs don’t just build kits; kits help build talented amateurs. And healthy innovation cultures—and successful innovation economies—need the human capital that their talent embodies. Kits are integral, indispensable, and invaluable ingredients for new value creation.

- There’s a low barrier to entry. It doesn’t take huge capital expenditures to start a kit business. Especially with the presale method of Kickstarter, you can get your business off the ground with very little cash at the outset. It’s easier to budget the costs and expenses of running a business when the bill of materials (BOM) remains exactly that: raw materials. Adding in the real estate, insurance, and kit-packing labor costs will give you a “good enough” idea of the economics that make your business work.

- There’s also a growing outlet and distribution channel for well-designed and popular kits. In addition to marketing through Kickstarter, companies like Adafruit and SparkFun as well as Make:’s Maker Shed are becoming effective distribution channels for makers to get their projects out to a wider audience.

Going from zero to one and then from one to one thousand has never been more possible for makers like you and me. But getting to 1000 true fans is still a monumental task. Even though the process is made easier with the new digital fabrication tools and Internet distribution models, it’s an immense challenge (not to mention the new challenges that arise when product demand increases and orders start to number in the thousands).

Makers are becoming entrepreneurs, and in true maker style, they are going about it in a radically collaborative way.