Good Practice in Leadership and Management

Overview

This chapter examines good practice of leadership and management, discussing the qualities and skills required to act as the senior manager of a nonprofit sector organization. More is described in Chapters 7 and 9.

This chapter concentrates on the attributes required as the senior manager of a nonprofit organization, either an independent organization or one operating within a larger entity. Professional management standards and literature are drawn on. However it has also been relevant to draw on 25 years’ practical management experience on the ground, feedback from colleagues and coaches and the actual experience of being managed, to identify the essential competences.

Background to Nonprofit Organization Management

The role of the senior manager is very different within a small nonprofit organization, with different skills required, more management necessary, while significant service delivery expertise is required as there are no cohorts of service experts in support.

Specific qualities are required for managing in the nonprofit sector. Peter Drucker in a specialist book points out that nonprofit stakeholders are much more varied and important than in “the average business” (Drucker 1990). Jim Collins states there is a “diffuse power structure” in the nonprofit sector, which in turn makes management harder (Collins 2005).

Most authorities agree “the single most important determinant of the success of an organization is the quality of its leadership” (Bolton and Abdy 2007). However the job of leading an organization effectively is highly complex, with no magic formula to provide good leadership to be replicated everywhere. In fact Barbara Kellerman has written that years and years of “leadership studies” have made little progress in clarifying what leadership is or how to teach it (Kellerman 2012).

The qualities required will obviously vary considerably according to the context in which they are deployed, namely the objectives and activities of each organization, the services being provided, the organizational structure (company structure, Board setup), size (budget, staffing, numbers of team leaders), funding (contracts, grants), and organizational culture. The role of the senior manager will be critically affected by these organizational issues; for instance, in large organizations there are specialist Human Resource (HR) departments, whereas in small organizations most, or even all, of the major personnel issues have to be dealt with by the senior manager, albeit with advice.

Certain areas of specific knowledge should not be considered essential for managers, as they can be easily bought in or accessed, for example, legal knowledge, while other skills can also be learnt quickly; for example, IT spreadsheets. It is the fundamental skills and qualities of leadership and management, on which I concentrate.

Key Qualities of Leadership and Management

The following list of leadership and management competences comes from the UK Management Standards (2008). The full list stretches over many pages and they have often been adapted by organizations for their own policies: for instance, a UK college has a 13-page competency framework for managers, while nonprofits have also drawn up their own lists.

One of the summary lists gives an overview of the breadth and depth of skills and qualities required for leadership and management:

1. Create a vision of where your project is going, communicate it clearly and enthusiastically, with objectives and plans, to people in your team.

2. Ensure your people understand and see how the team’s vision, objectives, and operational plans link to vision and objectives of overall organization.

3. Steer your team successfully through difficulties and challenges, including conflicts.

4. Create and maintain a culture in your team, which encourages and recognizes creativity and innovation.

5. Develop a range of leadership styles and select and apply these to appropriate situations and people.

6. Communicate regularly, making effective use of different communication methods, with all your people and show you listen to what they say.

7. Give your people support and advice when needed especially during setback and change.

8. Motivate and support your people to achieve work and development objectives and provide recognition when successful.

9. Empower your people to develop their own ways of working and take their own decisions within agreed boundaries.

10. Encourage people to give a lead in their own areas of expertise and show willingness to follow this lead.

11. Win, through your performance, the trust and support of your people for your leadership and get regular feedback on your performance.

These standards are quite general, consequently inexperienced managers may find it hard to understand exactly what they should be doing just from these. So it is important to examine key aspects and discuss how nonprofit organization managers should best implement these.

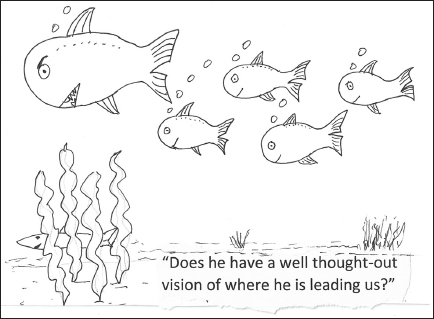

Forward Thinker

The senior manager in any organization needs to be forward thinking, with a vision of where they want the organization to go. They must act as a strategic thinker, devising a strategy for the organization (including a Vision and Mission), gain board agreement, with stakeholders and staff’s views taken into consideration as well. This will set a lead as to where the organization is headed, along with communicating this to staff and stakeholders. From the strategy, an operational plan needs to be developed for staff to work to, with attainable and measurable objectives.

Conditions are changing all the time, some funding is drying up, while other opportunities appear; sometimes this is because of a change of government or policy, sometimes economic pressures, social trends, or changes in markets. An example is that with the 2008 recession followed by the change of UK government in 2010, enormous cuts in government spending were imposed in the UK, specialist contractors were squeezed out and several nonprofit training providers were bankrupted. Similar cuts in government spending happened in the United States.

So new strategies are often required to cope with change, but innovation for innovation’s sake is not a good idea. Any new strategies must be carefully researched, devised, and considered, otherwise an organization can be endangered. It is quite possible for leaders to destroy a sound organization by moving into delivering impractical new services without carefully thinking through the consequences; this was demonstrated by the Novas Scarman charity’s sharp decline and ultimate demise based on their leadership’s bizarre strategy, inadequate governance and poor risk management (Third Sector 2010), elaborated in the following case study. Stakeholders are more important in nonprofit organizations than in private companies, where profits are the bottom line accepted by everyone; therefore stakeholders need to be consulted before major changes or innovation.

The senior manager needs to take the long view of where the organization is headed and plan ahead accordingly. This involves keeping properly informed and up-to-date about current and impending social, economic, and political policies and influences, which affect both the future direction and viability of the organization. This requires extensive reading, networking with key stakeholders, and careful planning ahead, after analyzing what risks are involved; in the 1990s one management role model told the author that good managers should read four daily newspapers to keep up-to-date with the business and political worlds; nowadays this would be done online, and one issue is making sure managers do not become overloaded with too much information.

It is essential for the manager to be objective and have a realistic view of their own organization’s strengths and weaknesses and the capacity to take on any new tasks and deliver the requisite outputs. They must play the long game, rather than settle for immediate short-term gains. Longer-term thinking can too easily be overtaken by day-to-day issues in a small organization where you have less chance to delegate work to others. As Peter Drucker said “The most important task of an organization’s leader is to anticipate the crisis” (Drucker 1990).

It is necessary to set aside sufficient time to ensure that rigorous thinking and planning happens; some managers use their own coaching sessions to examine difficult issues and plan ahead.

Setting an example seems a very obvious requirement for managers, even though it is not included in the standards. Adults learn through example and this applies even more strongly to organizations, where organizational culture is a strong factor in determining staff behavior. Managers must consistently set an example on almost everything, thereby communicating what is and isn’t permissible, what standards are required in the organization’s work and probity at work; this includes working the required hours, punctuality, no phone calls in meetings, no excessive private work or communication at work, and so on.

Staff model themselves on the senior manager, who sets the tone for the whole organization. An experienced teacher once told the author that the head teacher that they most admired after 30 years school teaching was always the first into school and last to leave (Davey 2012). Another teacher, with a 40-year track record who became a manager themselves, said that their worst school principal did not set an example, carrying out little work herself, reading a trashy newspaper in her office, and leaving essential tasks to the newly qualified teachers (Mulhare 2012).

If the manager sets an example, they can then be firm and consistent about setting performance standards throughout the organization. They can set the right tone, encourage high standard work, praise the work of the best staff and hold them up as exemplars, without showing favoritism, and so improve performance throughout the organization. It is also important to set boundaries on how close managers get to staff on a personal level, which can be hard especially in small, friendly organizations; but it helps maintain objectivity and avoids the dangers of favoritism being perceived by staff.

Motivating and Developing Staff

A manager must motivate their staff, although charismatic leadership is overrated.1 Managers should support their staff, who are the ones delivering services or working with clients or customers. Managers must set clear roles and responsibilities for each team member, so that it is obvious what is expected of them in terms of tasks, objectives, and standards.

On the other hand managers must not micromanage staff, watching too closely over results or directing operations in detail. This stultifies development and innovation, while senior managers should have more important things to do with their own time. The use of mobile phones enables staff to consult managers on difficult issues if necessary. Managers must encourage initiative among staff in a progressive way, encouraging them to use their own judgment more and more, even allowing them to make mistakes, from which they learn. Like a good parent the manager’s job is done if staff can operate successfully and autonomously.

Managers should make time to listen to staff and hear their concerns and ambitions, coaching staff to improve performance; encouraging staff to produce their own solutions to problems is more effective than telling staff what to do; putting time into learning coaching skills is invaluable for managers.

A lesson I learnt from my youth work was never to give an instruction that there is no chance of being obeyed (I subsequently discovered that this is also a guiding maxim in the armed services). Also managers should never ask staff to do anything they would not be prepared to do themselves. As staff become more experienced they should be empowered and given more responsibility as per situational leadership theory, proposed by Adair (Adair 1988) along with Hersey, and Blanchard (shown in Figure 1.1). Clearly the responsibility levels allowed to staff by the senior manager depends on the experience and skills of the staff concerned and the importance of the task undertaken.

Figure 1.1 Situational leadership

Balancing all the different aspects of management can be difficult but it is essential that managers think straight and get their priorities right. Time management is critical for managers but harder in small nonprofits where managers must multitask. As most nonprofits are small, the roles of senior leader and operational manager are invariably combined, while in bigger organizations the leader or CEO delegates day-to-day management to other managers, leaving more time for the leadership role. Without this separation of roles, difficulties arise; “Small businesses have been characterized by their lack of resources, lack of systems and largely idiosyncratic approach to management” (Mazzarol), which is as true for small nonprofits.

Managers of all size organizations can allow their priorities to become distorted, if they become bogged down in the wrong tasks. In large organizations particularly, the requirements of legislation and red tape, including health and safety, risk assessments, HR issues, often overwhelm and distract managers from concentrating on essential management. So prioritizing one’s tasks and time is essential (see Chapter 9).

Managers just working longer and longer hours does not help, nor working on activities with no clear understanding of their value to the organization; one example is the endless round of lengthy meetings, another is any interagency partnership, hamstrung by squabbling. There can be a danger of “substituting acquaintance for knowledge, activity for understanding, reporting for analysis, quantity of work for quality” as a senior UK ambassador once wrote perceptively (Meyer 2012).

Managers must deal with the necessary paper work efficiently, completing the necessary reports on staff, operations and funding, but must not let it take over their real work. Parkinson’s Law, “Work expands to meet the time available,” can be very dangerous. Missing deadlines for funding bids or sending returns in late to funders or government affects the organization’s budget and reputation or both, while keeping staff waiting for expenses loses their loyalty.

Balancing these different priorities and completing the tasks can be difficult; John Adair’s concept of overlapping management tasks (Adair 1973) is very relevant to most manager, who are continually having to juggle different priorities (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Overlapping leadership tasks

Entrepreneurial

The senior manager needs to be proactive, creative, and innovative, open to new ideas, evaluating the relevance and applicability of new opportunities and able to introduce new services successfully. Even in the charitable sector, managers need to be entrepreneurial, always on the lookout to make new contacts, to find and utilize new openings and raise funds for new projects and services. It is important that organizations are not skewed toward delivering unsuitable or unsustainable services solely in the pursuit of funds; however if the right level of resources is offered that fit with the organization’s strategy, then it is wise to follow up funding offers. Entrepreneurialism should be based on a realistic assessment and understanding of the state of the opportunities, proper risk assessment and an analysis of the returns from contracts and the capability of the particular organization managers are leading. Decision making is an absolutely crucial skill, and there are techniques available for managers to improve their ability in this area, such as coaching, as well as training. The Novas Scarman case study illustrates where due process was not followed and a viable organization was destroyed.

Case Study: The Demise of Novas Scarman

The initial genesis of the UK Novas Group in 1998 seemed both sensible and innovative as it merged three small charities providing care and housing to homeless people in London, Northern Ireland, and Liverpool, creating a much more effective organization, as at that time homeless charities were too small. Novas then expanded its provision into other towns with 2,000 housing units across the United Kingdom which stretched management capacity further.

In 2006 it was planning a £50 million redevelopment of its hostels and housing provision, but a Housing Corporation report of June 2006 warned that its proposed redevelopment could prove too ambitious as it lacked proper development capacity at this scale.

In 2004 Novas merged with Scarman Trust, a regeneration charity, and, as part of the hostel redevelopment, it then embarked on a highly ambitious arts center development. Arts funding in the United Kingdom provided much lower incomes when compared with running hostels, where 40 percent of the income came from government subsidies and was topped up with another 40 percent of government grants. In addition the steady increase in property prices in the United Kingdom, particularly in London, increased the asset base of hostel nonprofits, which owned their hostels, like Novas.

These difficulties were compounded by developing two arts centers in two different cities, with the Liverpool one costing £17 million, albeit with £6.5 regeneration grants. In addition the founding CEO, who also sat on the board, embarked on an expensive spree buying antique fittings, Malaysian art and other fripperies, exposed in a government agency investigation and publicized in the Daily Telegraph and he was forced out. The report raised concerns over “alleged cronyism, nepotism bullying, and mismanagement.”

A new board was appointed in 2009 after the investigation. Novas had to sell a large number of properties to its competitors, but still failed to sort out its finances and eventually had to sell its flagship, Arlington House, where George Orwell stayed in the 1930s. The organization was holed under the waterline by the time a new chair and CEO were appointed and the organization was relaunched as People Can in 2010. The pension commitments of £17 million were too great, the charity was wound up in 2012 and almost 300 staff lost their jobs.

One could conclude that some government grants would be so heavily cut back that it was wise for Novas Scarman to try to reduce dependency on these and switch to more trading and other activity. However, the lessons are that organizations should not be led into a new risky business area, if they have insufficient knowledge or experience to embark on this, when they have not fully researched the venture and assessed the risks of damaging an existing and stable organization. The move by Novas Scarman seems an example of “mission creep,” venturing into the unknown, without any clear evidence that this would benefit either the clients or the organization, set up to serve them. The regulator stated there were failures in management and clearly there was over-reliance on and lack of supervision of the charismatic founder; the new chair said the real lesson to organizations was that risk management and the ability to look at real case scenarios were critically important.

Communication Skills

Communication skills for managers include written and verbal skills obviously, but also networking and partnership skills. Most managers are stronger in certain areas of communication than others; a respected colleague once told me that a visionary manager, who founded three renowned UK charities which contribute enormously and still flourish 50 years afterwards, was no good in one-to-one situations with staff. (Later I discovered that his wife cofounded these charities and presumably supplied the necessary soft skills.) The converse can also apply, where a senior manager is good at one to ones with people but lacks drive or the ability to communicate with large numbers.

External networking is another necessary skill, including presenting a positive picture of the organization through conferences, articles, and presentations. Networking can also ensure that the organization’s tenders or bids do not land cold on someone’s desk but with a favorable impression already created.

In large organizations with numerous different departments, it is also necessary to network internally with colleagues to proceed more effectively and swiftly; for example, securing publicity for a project, ensuring a team’s jobs are advertised quickly, sorting your IT problems ASAP, or keeping the health and safety inspector happy. In many respects this is like carrying out community work but in the organization. This requires taking time out to get to know key staff, to find out how different staff perform and to make positive relationships with staff in key nonservice departments; for example, finance, HR, IT, and so on. This is particularly important in large organizations or those with head offices, which do not always have an adequate understanding of the issues facing frontline staff, particularly those hundreds of miles away.

Productive Relationships

The manager needs to build and maintain a range of constructive and positive relationships externally with potential customers, commissioners and funders, and potential partner organizations, through networking. It is far, far easier to become part of consortia bidding for contracts than going through the whole time-consuming process of tendering on your own, particularly as small organizations new to tendering lack both a track record and bidding expertise. This process is also likely to be more successful since partnerships are fashionable, the minimum size of contracts on some UK government tenders is high, often £1 million, and most tenders do not allow an organization to bid for more than 40 or 50 percent of current turnover. To be included in a consortium requires networking and your organization meeting certain standards (see Chapter 4).

Partnerships are being encouraged at many different levels; so skills in this area are also important, as your organization may be required to work with other delivery partners in a consortium or with a funder who wants to be involved in how the work is presented or publicized. Qualities required are tact, diplomacy, and patience.

Resilience and Adaptability

Resilience and adaptability are other important qualities, as the unexpected will arrive to confront the organization. These qualities are not always included on the lists of required qualities of managers and leaders yet it is absolutely crucial. All organizations face downturns and setbacks, not within their control, however much risk planning is in place. I agree with Murphy’s Law, which states if something can go wrong, it will, however many precautions have been put in place.

It is essential for leaders to be resilient, to demonstrate their resilience to the team and to lead the organization to overcome the setbacks. This is emphasized by one of the most prescient commentators on the most recent financial crash, Nassim Taleb (Taleb 2012), who describes the importance of a quality he designates as antifragility, which leaders need to deploy to ensure that their organizations become and stay resilient. Adaptability I see as the quality of making good, after something has gone awry.

Case Study

A new community project was set up for young offenders as an alternative to youth custody sentences and project went well for the first few months. One night after group work run by the least experienced staff member, some young men broke back into the day center, overcoming the burglar alarms, stealing the project minibus, photocopier, and much other equipment. The theft was not discovered until the next day and the demoralized staff were stunned and confused about what needed to be done, both with regard to practical steps, understanding the motives of the young people involved and feeling motivated. The manager was upset by the incident, but they had experienced several similar incidents previously in other projects. So the manager took the lead, instigating a review of work practices, improving security and working with the young staff member to enable them to understand what had really happened and the reasons for this.

This resilience and adaptability enables managers to deal with, not avoid, unpleasant or fraught situations. Providing services to clients and customers in the community makes organizations potentially vulnerable to complaints, issues, and problems thrown up by relations with clients or customers or with regulators and commissioners, which must be dealt with effectively and in a short time scale, otherwise adverse comment or publicity can ensue and affect the organization’s standing; the UK Kids’ Company charity was wound up after a complaint about abuse of a client triggered greater scrutiny of its finances and management; subsequently the abuse story proved unfounded but by that stage the mismanagement was clear to all.

Expertise in Operations

The senior manager must be perceptive, with a certain level of intellect and intellectual curiosity rather than intellectual brilliance. They must have experience in and knowledge of their specific profession or industry, sufficient to provide relevant leadership, with good understanding of the services they are providing and the markets they are tackling.

According to research (Goodall 2012), organizations run by expert leaders—those with deep technical knowledge and experience in the organization’s core business—perform better than those organizations where general managers are in charge. The expert leaders make better managers because of their deep-rooted technical knowledge, which helps them devise and implement more effective and intuitive strategies. This expertise enables them to manage in a more sophisticated way, rather than just relying on crude numerical targets. Also the managers’ own track record and reputation in turn helps recruit and retain other talented staff.

The use of IT has spread rapidly, particularly the Internet, which is now being used for promoting organizations and fundraising. In addition more online data and reporting systems are being used to capture and report on information about service outputs across organizations. Most applications can be learnt. But in this rapidly changing technological society, it is clear that a minimum level of IT literacy is now an essential attribute for managers. This is not just expertise in specific IT applications, such as spreadsheets or social media, but sufficient understanding to be able to make decisions with reasonable knowledge as to how IT can best help an organization.

Likewise there is a minimum level of financial skill required for all managers so that they can budget, produce accurate financial projections, understand what accounts mean and plan ahead properly. In all sectors budgets must be balanced or organizations will be wound up, resources must be shifted to relevant areas, and potential funding gaps tackled. Unrealistic projections of income for nonprofit organizations bring organizations down. Currently the pension shortfalls have led some nonprofits to owe more in pension commitments than their current or prospective income can cover, so prudent organizations are changing their pension arrangements.

Emotional Intelligence

I am skeptical of unproven methods and their effectiveness, but it is clear that emotional intelligence and soft skills are essential qualities in managers. Ten years ago the term emotional intelligence was not used with regard to management; instead other terms such as human understanding or people skills might be used, But Dale Carnegie’s famous book How to win friends and influence people in 1936 was an example of using soft skills. It is now accepted that emotional intelligence is an essential ingredient for managers in all sectors, This is even more true of nonprofits because they deliver social objectives and most involve providing services for people.

Even in strongly hierarchical and military organizations such as the 19th century UK Navy, leaders such as Admiral Nelson were admired for their care for their seamen (Lambert 2009). Understanding how to get the best out of their own staff is essential; one senior military officer used to visit underperforming staff in their own offices to put them at their ease (Macdonald 1982). This tactic—management by walking around—is very valid as it enables the manager to see what is really going on, gain feedback, discuss progress with staff on a more equal basis and be seen to on the frontline.

Emotional intelligence can be developed or improved by managers reflecting on their own personality, relationship, and performance. A 360-degree feedback can be a useful tool, where managers obtain feedback from both staff they manage as well their own chair or senior manager. This process can be painful for oversensitive managers so another strategy is for managers to arrange to be coached to ensure they receive feedback on their own performance, gain understanding, and become more objective.

In different management structures, there will be also specific skills managers need, for instance skills in dealing with management boards or unions may be required in those nonprofit organizations where these exist. In specific nonprofit organizations there will also be specialist service knowledge, which managers need to acquire, supervise, and challenge the specialists in their own teams.

Conclusion

The most crucial areas for management and leadership in nonprofit organization are combining an entrepreneurial quality with people skills and with experience and expertise in the specific operational area being tackled. Any competent manager will utilize entrepreneurial flair, people skills and operational experience to generate new ideas about new services from staff and others, thereby renewing services or setting up new ones.

Managers need to develop their own leadership and management style and aptitude and be confident in that. They need to learn new skills all the time and be open to new ways of working (see Chapter 7). Leadership in this ever-changing world has become more and more pressured; expectations are higher and higher to produce results. On the other hand there are more leadership training programs and coaches available to assist managers to develop their own specific leadership styles and make the grade.

To sum up leadership succinctly, here is an example from the arts field, where Deborah Bull, Creative Director of the UK Royal Opera Ballet, defined leadership as being based on hard work: “A strong sense of values, values which are derived from repeatedly working on yourself, on your profession, the sense of discipline, the sense of team work, the sense of playing the long game, the sense of learning from failure, and that constant pushing the boundaries forward while respecting the past.”

Do’s and Don’ts for New Leaders

1. Be positive, be resilient, and set a lead in the organization at all times.

2. Look after yourself, recruit a coach or join a support group to test out your ideas, sustaining you through the inevitable hard times.

3. Do make sure you properly understand the finances, budgets, and contracts.

4. Stay well informed and plan ahead, including analyzing the worst possible scenarios.

5. Do project a good image of your organization’s work, using proper evaluation and case studies.

6. Listen to your staff; they know better than you as to what is really going on at the coal face, even though they won’t always be right about what to do next.

7. Do not take any management job offered to you; find out what is really happening in the organization, its future prospects and the staff you would be managing.

8. Don’t work on your own, but find key people to form a team to work with.

9. Don’t boast, but do underpromise and overdeliver.

10. Don’t allow your organization to be dependent on one source of income, but diversify.

11. Don’t show fear and panic, however much you feel it inside, but set an example even in the most difficult of times.

References

Adair, J. 1973. Action-Centred Leadership. London, England: McGraw-Hill.

Adair, J. 1988. Effective Leadership. London, England: Pan Books.

Bolton, M., and M. Abdy. 2007. Paper for Clore Duffield Foundation http://cloreduffield.org.UK/downloads/SLPConsultationPaperJuly07.pdf

Bull, Deborah. 2013. BBC Radio 4.

Collins, J. C., and Collins, J. C. 2005. Good to great and the social sectors: why business thinking is not the answer: a monograph to accompany. Boulder, CO: J. Collins.

Davey, E.K.D. 2012. Personal Communication to Author.

Drucker, P. 1990. Managing the Non-profit Organization: Practices and Principles. New York: Harper Collins.

Goodall, Dr AH, https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=ad0XFggAAAAJ&citation_for_view=ad0XFggAAAAJ:hqOjcs7Dif8C

Kellerman, B. 2012. End of Leadership. New York; Harper Collins.

Lambert, A. 2009. Admirals. London, England: Faber and Faber.

Macdonald, Air Vice Marshal DMT (CB, former Director General Personnel) personal communication to his son, the author 1982

Management Standards. 2008. http://management-standards.org

Mazzarol, T. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/13552550310461036

Meyer, Sir Christopher, 2012, BBC Radio 4

Mulhare, K.T. 2012, personal communication to author

Taleb, N. 2012. Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. London, England: Penguin.

Third Sector 2010. http://thirdsector.co.UK/andrew-barnett-chair-novas-scarmangroup/governance/article/976364

Williams, I. 2007. “The Nature of Highly Effective Community and Voluntary Organizations.” http://www.dochas.ie/sites/default/files/Williams_on_Effective_CVOs.pdf

1 www.forbes.com/sites/adigaskell/2017/05/31/should-we-beware-charismaticleaders/#7b39f58a27df